Purepecha empire

Pre-Hispanic State | ||||

| ||||

| Capital | Tzintzuntzan | |||

| Main language | Purepecha | |||

| Religion | Politheist | |||

| Government | Monarchy | |||

| Right or Cazonci | ||||

| • 1370-1420 | Tariácuri | |||

| • 1450-1486 | Tzitzispandácuare | |||

| • 1486-1520 | Zuangua | |||

| • 1520-1530 | Tangáxoan Tzintzicha | |||

| Historical period | Pre-Columbian America | |||

| • Tzintzuntzan Foundation | c. 1200 | |||

| • Agreement with Spanish | 1530 | |||

| Surface | 75 000 km2 | |||

Notes Gentile: purépecha | ||||

The Purépecha Empire (in Purépecha, Pꞌurhépecherio) or Tarascan Empire was an empire in pre-Columbian Mexico, covering part of both the region Mesoamerican as well as Aridoamerican and an extensive geographical area of the current Mexican state of Michoacán, parts of Jalisco, southern Guanajuato, Guerrero, Querétaro, Colima and the State of Mexico. At the time of the conquest it was the second largest state in Mesoamerica. Their government was monarchical and theocratic, and like most pre-Hispanic cultures, the Purépechas were polytheistic.

Introduction

The Purépecha state was founded near the turn of the 14th century and lost its independence to the Spanish in 1522, briefly subsisting thereafter as a vassal kingdom of the Spanish Crown until the death of the last Irecha in 1530 at the hands of Nuño de Guzmán. The empire's inhabitants were mostly Purépechas, but other ethnic groups such as the Nahuas, Otomi, Matlatzincas and Chichimecas were also included. These ethnic groups were gradually assimilated into the majority group.

The state was made up of a network of tax systems and gradually became centralized under the control of the state governor who was called irecha. The Purépecha capital was in Tzintzuntzan on the shores of Lake Pátzcuaro, Michoacán; According to the Purépecha oral tradition it was founded by the first Irecha Tariácuri and dominated by his lineage, the Uacúsecha (& # 39; eagles & # 39;).

The Tarascan state was a contemporary and enemy of the Mexica Empire, against which it fought many times; it blocked the expansion of that nation towards the west and southwest, and, through a series of fortifications, they protected its borders; which possibly gave rise to the development of the first truly territorial state of Mesoamerica and Aridoamerica. Between 1476 and 1477 the Tarascans defeated the Mexicas commanded by the tlatoani Axayacatl and managed to invade their territory on numerous occasions, succeeding on several of them and conquering important cities such as Xicotitlán, Tollocan and Oztuma.

Controversy between Purépecha and Michoacán

Regarding the way in which this state should be called, there is discussion among anthropologists, historians and archaeologists.

- The term michoacano arises in the centuryXVI of the Nahuatl michhuahqueh, with which they were referred to the inhabitants of the area of Lake Pátzcuaro, since it means "habitants of the place where fish abound".

- The word Pure I mean, common people in the homonymous language and designates the largest segment of the pre-Hispanic population of the Tarasco state, as well as the current speakers of the pururhé.

- The word tarasco has been proposed to come from the word Tarasque which means son-in-law or father-in-law in a purépecha language, and so the conquerors call the purépechas, so that word is like an insult.

- The term hear it.which means eagles in purépecha, was used in the centuryXVI to refer to the founding peoples of the purépecha state.

Usually the term Tarascan is used to refer to said cultural group during pre-Hispanic times and Purépecha for contemporary times. The name claimed by the inhabitants of the current indigenous communities is purépechas.

Geography and area of occupation

The territory that made up the Purépecha state is part of the transversal volcanic zone, and is located in its western extension, between two large rivers: the Lerma (belonging to the arid-American zone) and the Balsas. However, the Purépecha state was centered around the Lake Pátzcuaro basin. It included temperate, subtropical, and tropical climate zones, which are dominated by Cenozoic volcanic mountains and lake systems above 2,000 meters, although it also includes lower-lying areas such as the southwestern coastal regions. The most common soil types on the central plateau are young volcanics or Andosols, Luvisols, and the less fertile Acrisols. The vegetation is made up mainly of pines, pine-oaks and firs. Human occupation has focused on the lake basins, which are abundant in resources. In the north, near the Lerma River, there are resources such as obsidian and hot springs.

History of the Purépecha state

Archaeological evidence

The Purépecha area has been inhabited at least since the early Preclassic period. There is evidence of early agricultural societies from before 1800 BCE. C. as the grave-making culture of "el Opeño". The earliest radiocarbon dates at Preclassic archaeological sites fall to around 1800 BCE. C. and the best-known preclassic culture in Michoacán is the Chupicuaro culture, which is considered to have inhabited between 800 B.C. C. to 100 d. C. Most of the Chupícuarense sites are found in the Cuitzeo lake basin.

Influence from Teotihuacán has been found in manifestations such as monumental architecture, ceramics from the classical period.

Ethnohistorical sources

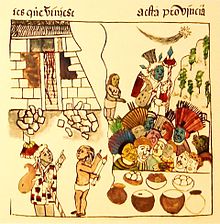

Although the use of codices in Michoacán for pre-Hispanic times is indirectly mentioned, the truth is that all pictographic documents of indigenous origin known up to now are colonial. The indigenous peoples of Michoacán adapted their discourses within the new viceregal order, preparing their own documents that were used as legal instruments to vindicate claims, so the information contained must be contrasted with other sources. In these pictographic documents, the indigenous people recorded part of their memory of the pre-Hispanic past.

By the 17th-18th centuries, another genre of texts with written characters appeared, which today are known as “primordial titles”, some accompanied by paintings. These documents contained the founding or re-founding history of the town, but given the non-Western nature of indigenous memory, these documents do not have chronological coherence and events from different periods are often mixed up. The genealogies of caciques, historical annals and the demarcation of territorial limits are also mentioned, which served to vindicate the political rights of the caciques or over the land before the Crown.

More than twenty pictographic documents of indigenous tradition are known, made in Michoacán during the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries, and they have received different nomenclature by scholars. Several are kept in archives and museums, others have ended up abroad or in private collections, many have been lost over time, and some still remain unpublished in various indigenous communities. They were made with different materials, such as amate, maguey, European paper or cloth, with a complex iconography and most of them glossed with Latin characters.

The following list of indigenous pictographic documents from Michoacán, their nomenclature and date, has been taken from the investigations of Hans Roskamp, although there are many other documents that have not been investigated, or have disappeared. The previous name with which it was known is placed in parentheses to avoid confusion with the most mentioned, the year of its elaboration when it is known; the place of manufacture corresponds to its name, unless otherwise indicated in brackets.

Among the documents of the XVI century we can mention:

- La Relationship of Michoacán', (also known as Scurial Codex), 1541 [Tzintzuntzan-Pátzcuaro]. This is the most important ethnohistoric source for the past of Michoacán, it was written between 1539-1541 by the Franciscan Fray Jerónimo de Alcalá (♪1508-1545), contains translated and transcribed accounts of noble jars. This relationship contained three parts of the "Uacosecha official history", which was preserved through oral tradition: the first part focused on the religion of the Tarasco state, unfortunately, of the first part only a leaf is preserved; the second part deals with how the ancestors of the Cazonci They conquered the center of Michoacán; and the third part deals with society and the Spanish conquest.

- La Memory of Don Melchor Caltzin1543 [Tzintzuntzan].

- The Huetamo Codex and Codex of Cutzio1539-1542.

- The Cannzo de Jicalán (formerly) Cannzo de Jucucataco1566.

- The “Hueapan” group codexes produced in 1567, among which are the Codex of Valladolid, the Axacuary Codex, the Codex of Zinapécuaro, the Codex of Querendaro, the Picture map of Queréndaro, the Irapeutic Codex I, the Figure II and Figure III.

- The shield Weapons of the City of Zintzuntzan Vitzilan of the province of Michoacán1595.

These documents are known from the 17th century:

- The Jaracuaro Codex.

- Them Titles of Tocuaro.

- The Cannzo de Aranza (formerly) Cannzo de Sevina).

- Them Tarecuato anals, this is a very important document of the same centuria, but only of Latin characters, where several very important events were recorded from 1519 to the year of 1666.

Between the 17th and 18th centuries, several indigenous documents were produced that rescued part of the pre-Hispanic memory, among which are:

- The Chilchota Codex.

- The Cannzo de Puácuaro.

- The Cannzo de Nahuatzen.

- The “Corpus de los títulos de Carapan”, is the richest set of documents in information of its type, made up of Carapan Codex, Codex Plancarte, Genealogy of Carapan caciques, Carapan Canvas, Cannzo de Pátzcuaro and Document of Tulane.

The following pictographic documents are known from the 18th century:

- The Codex Tzintzuntzan.

- The Cannzo de Comachuén.

- The Cuara Codex [Pátzcuaro].

On these documents, there is still a need to carry out investigations, to know the context of elaboration and for what purpose they were used, and to interpret the present iconography, which will enrich the history of the Michoacán past.

Foundation and expansion

At the beginning of the Postclassic period, there were various non-p'urhépecha ethnic groups living in the current state of Michoacán; groups of Otomi, Matlatzincas, groups "Toltecoides" and Nahuas, covered most of the territory and a "prototarascan" called ziranbanecha that inhabited Naranján.

The Uacúsecha arrived in the region around the year 1200 from somewhere in the north, settling on the Uringuarapexo hill (present-day El Tecolote hill). It is said that they asked the chief of the Ziram Bénecha to worship the god Curicaveri (God of fire) and pay tribute, the chief of these (Ziraziracámbaro) was outraged by the demands of Ireti Ticatame (leader of the Tarascans). However, the military superiority of the Uacúsecha prevented the Ziram Bénecha from launching an offensive, they gave Ireti tribute and the sister of their leader, Pispérama i>who had a son with him; They named her son Sicuirancha .

Later on, the Zirambénechas and Tarascans came into conflict, the latter had to leave the hill where they were lying to emigrate to a town near Pátzcuaro called Zichaxucuaro, there they stayed for the rest of the reign of Ireti Ticatame who died in a war against the lords of Cumachen, who also burned down the town. When Sicuirancha and other men arrived from the hunt they found the village on fire, this then along with his warriors attacked Cumachen and destroyed them. So the defeated were subdued and the capital was renamed Huayameo.

Sicuirancha died around the age of 90, inheriting power from his son Pauácume.

The chiefdom of the Tarascans then entered a stable and prosperous period in which five cazonci reigned.

A visionary Tarascan leader named Tariácuri, son of the lord of Pátzcuaro Tzetahcu, decided to unite the communities around Lake Pátzcuaro creating the Purépecha kingdom. Around 1300 the first conquests were carried out and already during his old age he put three of his descendants in power, dividing the kingdom into three large fractions: Señorío de Huiquingaje (Son of Tariácuri) in Pátzcuaro, Señorío de Hiripan (Sobrino de Tariácuri) in Ihuatzio and the Lordship of Tongaxoan I (Tariácuri's nephew) in Tzintzuntzan. With the death of Tariácuri (around 1350), his lineage maintained control of the main centers around Lake Pátzcuaro. His nephew Tangaxoan I continued the expansion in the area around Lake Cuitzeo and his son Tzitzipandacuare, later reunited the three lordships thus forming the empire.

Tzitzipandacuare began to institutionalize the tax system and consolidate the political unity of the empire. He created an administrative bureaucracy and divided responsibilities for tribute from conquered territories between lords and nobles. In the following years, the first Purépecha mountain range and then the Balsas River were incorporated into the State, which was increasingly centralized.

During the reign of the irecha Tzitzi Pandáquare several regions were conquered, it was the peak point of the state of Tarasco, since Tzitzipandacuare would manage to expand the territory to the current states of Jalisco, parts of Guanajuato, Querétaro, State of Mexico, Colima and Guerrero. In Guanajuato he managed to defeat the Aridoamerican Chichimeca tribes of & # 34; Pames & # 34;, & # 34; Jonaces & # 34;, & # 34; Guamares & # 34; and "Tecuexes" establishing an empire that covered 2 regions: Mesoamerica and Áridoamerica (south), establishing the lordships of Kuanasii Ato (Guanajuato), Yuririapundaro, among others. Tzitzipandacuare also managed to defeat the Tecos de Jalisco and the surrounding chiefdoms, thus forming the lordships of Chapala, Tuxpan and Sayula that covered a large part of the current state of Jalisco. In 1460 the Tarascan state reached the Pacific coast, conquering the Zacatula region.

In 1470 the Aztecs under the command of Axayacatl captured a series of Matlatzinca cities in the western region of the current State of Mexico, causing a Pirinda/Matlatzinca exodus to Michoacán, who were welcomed by the Irecha. The Aztecs invaded Tarascan territory, being stopped at the border, in the city of Taximaroa, where both armies staged the largest battle in pre-Columbian Mexico where the Tarascan army was finally victorious, causing one of the most painful defeats of the Aztec empire. Tzitzipandacuare soon mounted a counteroffensive and invaded Aztec-controlled territory, taking cities such as Xicotitlan, Temascaltepec, Ixtalhuaca, and Tollocan (Toluca). This experience made the Tarascan ruler further strengthen the border with the Aztecs, setting up military centers along the border, such as in Cutzamala (State of Guerrero), where the Tarascan irecha created a garrison of warriors whom he called Apatzingani. Like most of the wars of that time, the conflicts between the Mexica and Tarascans were also religious battles, during this period the Tarascan warriors in Cutzmala had the obligation to harass the Mexica fortified in Oztuma, and what They were compulsorily painted black to honor the god Apatzi (God of death). It also allowed Otomi and Matlatzincas who had been expelled from their lands by the Aztecs to settle in the border area on the condition that they participate in the defense of the Tarascan lands. From 1480 the Aztec ruler Ahuizotl intensified the conflict with the Tarascans, mainly in the hot land. He supported the attacks on the Tarascan lands with other ethnic groups allied or subjugated by the Aztecs such as the Matlatzincas, Chontales and Cuitlatecos. The Tarascans, led by the Irecha Zuangua, repelled the attacks commanded by the Tlatoani Moctezuma Xocoyotzin, who commanded an army commanded by the Tlaxcalteca "Tlahuicole". The Tarascan expansion was interrupted until the arrival of the Spanish.

Faced with Mexica pressure, the Tarascans formed a series of extremely powerful lordships that were at the service of the capital Tzintzuntzan that Father Beaumont identifies with the total extension of the Purépecha empire, this statement being erroneous by including the kingdoms of Collimán (Colima). and Xalisco (Jalisco and Nayarit); the borders mentioned by Father Beaumont on his map & # 34; Ithnographic plan of the Kingdom of Michuacan and states of Greater Caltzontzin & # 34; correspond to those of said confederation; Its borders were as follows: It began south of the current state of Guerrero passing through Atoyac, Tepecuacuilco and Iguala, in the current state of Mexico passing through Temascaltepec, Tlapujahua and Ixtlahuaca, then to the north passing between Querétaro and San Juan del Río, through the Sierra de Xalpa, turning northeast from Xichú to Apaseo, then along the Lerma River to Papasquiaro, from there northwest to Rosario and Chiametla in Sinaloa.

Fall of the Tarascan state

After hearing about the fall of the Mexica empire, the Irecha Tangaxuán II sent emissaries to the Spanish victors. Some Spaniards went with them to Tzintzuntzan, where they presented themselves and exchanged gifts. They returned with samples of gold and Cortés's interest in the Tarascan state was aroused. In 1522 a group of Spaniards under the command of Cristóbal de Olid were sent to Tarascan territory and reached Tzintzuntzan in a matter of days. The Tarascan army numbered many thousands, perhaps as many as 80,000 warriors, but at the crucial moment they decided not to fight. Tangaxuán handed over the lordship to the Spanish Crown, which allowed it to maintain the throne and some autonomy. This gave rise to a strange arrangement in which both Cortés and Tangaxuán were considered Michoacán's own rulers in the following years: the population of the area paid homage to both. Years later, in 1529, Cortés was deprived of the governorship of New Spain and traveled to Spain to settle the matter. Meanwhile, Nuño de Guzmán, president of the First Court of Mexico, had seized power. In 1529, upon the news that Cortés was returning to Mexico, Nuño de Guzmán left for the west, which would lead him to pass through Michoacán and carry out justice against the irecha. There Nuño de Guzmán allied himself with a Tarascan nobleman Don Pedro Panza Cuinierángari, the result was the death of Tangaxuán. A period of violence and instability began. Over the next several decades, Tarascan puppet rulers were installed by the Spanish government, when Nuño de Guzmán had fallen from grace Bishop Vasco de Quiroga was sent to the area to evangelize them. He quickly earned the respect and friendship of the natives who left the hostilities against the Spanish hegemony.

Economic activities

They dedicated themselves to pottery, sculpture, architecture, painting, goldsmithing and, notably, fishing was and continues to be a primary activity for the Purépechas. They were also the only ones who handled bronze for what was one of their secrets.

Important rulers

The highest authority was called Irecha (in Purépecha irecha, in Nahuatl caltzontzin). Some rulers stand out:

- Iretiticátame: decided that the people would settle in the territory that is currently the state of Michoacán, Mexico.

- Tariácuri: was founder of the Tarasco kingdom and considered the first sovereign of it.

- Tzitzíspandácuare: managed to centralize power in Tzintzuntzan by 1450. He made many conquests in Zacatula, Colima, Jalisco, and his armies defeated the Mexicas on various occasions.

- Zuanga: Upon learning about the development of the Tenochtitlan Conquest, he received peace ambassadors sent by the Huey Tlatoani Cuitláhuac. He sent his own emissaries to evaluate the situation and preferred to stay out, denying Cuitláhuac the assistance requested. He died because of the smallpox epidemic, shortly before the Spaniards arrived at the Purepecha Plateau.

- Tangáxoan Tzíntzicha: son of Zuanga, last tarasco. He received new requests for help from Cuauhtémoc, because Cuitláhuac, like his father, had died because of the smallpox. The refusal of the new fuss was overwhelming because he ordered the killing of the Mexican emissaries. Emissaries were sent to negotiate peace with Hernan Cortes in Coyoacán. The Spanish conqueror made artillery to impress the jars. Tangáxoan Tzíntzicha preferred to receive Cristóbal de Olid peacefully on 25 June 1522. After almost eight years of coexistence with the Spaniards, peace was broken by Nuño de Guzmán, who in search of wealth, murdered Tangaxan by causing the uprising of the jars.

| Cazonci | Regulation |

|---|---|

| Ireti Ticátame | ? |

| Sicuarancha | ? |

| Pauácume | ? |

| Uápeani | ? |

| Cover me | ? |

| Pauácume II | ? |

| Uápeani II | ? |

| Tzétahcu | ♪ 1350 |

| Tariácuri | 1370-1420 |

| Tangaxoán I | 1420-1450 |

| Tzitzispandácuare | 1450-1486 |

| Zuangua | 1486-1520 |

| Tangaxan II Tzíntzicha | 1520-1530 |

Main Cities

Sacred City: Zacapu Harócutin Pátzcuaro, which means "Stone on the Shore Where They Dye Black".

Centers of power during the triumvirate: Tzintzuntzan ("Place of Hummingbirds"), Pátzcuaro and Ihuatzio ("Place of Coyotes").

Imperial capital: Tzintzuntzan

Mythical cradle: Zacapu ("Place of stones")

Sacred Forest: Uruapan, place where the last Tarascan emperor hid

Gods

The Purépecha were polytheistic, their main god was Tiripeme Curicaueri ("Precious that is Fire"), however he was also the main deity of gatherers, hunters and war. They also highlight:

- Curicaveri (the great fire): patron god of the Uacusecha lineage ("aguilas").

- Tucupacha: God begotten of heaven, a couple of Cuerauaperi; he sent rains and gave life and death.

- Cuerauáperi o Kuerajperi: ("The One Who Unties"), represents the Moon, is the mother of the gods. Deity related to the sky and the rain, because he was considered the producer of the clouds, helped her four more deities, which were her daughters: Red Cloud, White Cloud, Yellow Cloud and Black Cloud.

- Xaratanga: the one that appears in all and various parts, is an advocation of the Moon or Cuerauáperi, lady or mother moon or new moon.

- Pehuame: the parturienta, is another advocation of Cuerauperi or of the Mother Moon. It is the deity of childbirth and wife of the Sun. His main centre of worship was in Tzacapu.

- Nana Cutzi: the coveted mother. Today the purépechas continue to use the name to refer to the moon.

- Tata Jurhiata: Father Sun, a name that today purépechas give the sun as a natural element and not deity.

Contenido relacionado

Calgary 1988 Olympics

Anastasius II (pope)

Mary I of Scots