Proto-Indo-European religion

The Proto-Indo-European religion is the set of myths, deities, and beliefs practiced by the Proto-Indo-European peoples, the hypothetical speakers of the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European language. While there is no direct evidence for mythological motifs – as Proto-Indo-European speakers lived in preliterate societies – comparative mythology scholars have reconstructed details from inherited similarities between Indo-European languages, based on the assumption that parts of the original Proto-Indo-European belief systems survived in inherited traditions.

The existence of similarities between the gods and religious practices among the Indo-European peoples suggests that whatever populations they formed had a form of polytheistic religion. In fact, what is known about Proto-Indo-European religion is based on conjecture based on the later history of Indo-European peoples, on linguistic evidence common to Indo-European languages, and on comparative religions.

The Proto-Indo-European pantheon includes a number of safely reconstructed deities, as they are both cognates—linguistic brothers of a common origin—and associated with similar attributes and body of myths: such as *Dyḗws Ph₂tḗr , the god of daylight-sky; the consort of him *Dʰéǵʰōm, the earth mother; the daughter of him *H₂éwsōs, the goddess of dawn; the sons of him the Divine Twins; and *Seh₂ul, a sun goddess. Some deities, such as the weather god *Perkʷunos or the shepherd god *Péh₂usōn, are only attested in a limited number of traditions – Western (European) and Greco-Aryan, respectively - and, therefore, could represent late additions that did not spread through the different Indo-European dialects.

Some myths can also be dated safely to Proto-Indo-European times, as they present linguistic and thematic clues to an inherited motif: a story depicting a mythical figure associated with thunder slaying a multi-headed serpent to release torrents of water that had previously been withheld; a creation myth involving two brothers, one of whom sacrifices the other to create the world; and probably the belief that the Otherworld was guarded by a watchdog and could only be reached by crossing a river.

Several schools of thought exist on possible interpretations of reconstructed Proto-Indo-European mythology. The main mythologies used in comparative reconstruction are Indo-Iranian, Baltic, Roman, and Norse, often also supported by evidence from Celtic, Greek, Slavic, Hittite, Armenian, Illyrian, and Albanian traditions.

Enough clues to this ancient religion can be found in overlaps between languages and religions of the Indo-European people to presume that this religion existed, though any details are conjecture. While similar religious customs among Indo-European peoples may provide evidence of a shared religious heritage, a shared custom does not necessarily indicate a common source for that custom; some of those practices may have arisen in a process of parallel evolution.

According to some informative essays, at the root of Indo-European culture there was already the belief that something exists after death, as revealed by the grave goods of the Kurgans and other documented archaeological remains.

Researchers such as Marija Gimbutas, Antonio Blanco Freijeiro and Georges Dumezil affirm that the first nature of the various gods that the different Indo-European peoples worshiped was probably of a celestial, atmospheric or even astrological character, assuming the idea that the divinities lived in the heavens and from them they manifested. In fact, the great Indo-European gods, such as the Norse Thor, the Hittite Tarhun, the Indian Indra or the Greek Zeus, are Lords of Lightning.

Other authors, on the other hand, such as Antoine Meillet, are skeptical of the idea of a root religion among the Indo-Europeans, due to the enormous diversity of cults identified from the oldest sites.

In fact, cultural practices among Indo-European peoples are so varied that it is impossible to pinpoint a single ritual dating back to the Common Period. But next to the "positive cult" (sacrifice) where the conception has been manifested as contradictory, there is a "negative cult" consisting of prohibitions. The vocabulary distinguishes within several languages a positive sacred and a negative sacred.

In Indo-Iranian, the root iazh, which designates worship in general, etymologically means 'not to offend', 'to respect'. A similar evolution occurs in the Greek of historical times with the verb σεβασμός (sevasmós). In Old Germanic, the replacement of the old name of the gods *teiwa (*deywo) by *guda «libation», is only understandable from expressions such as "respect libations (accompanying solemn pacts"). Finally, it is from the negative cult that the designation of «religion» was created in the majority of European languages: in Latin, religio means 'scrupulous, scrupulous respect', particularly in what concerning covenants: the religio sacramenti ('respect for the given word').

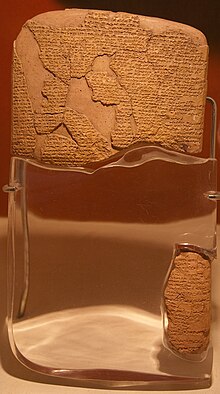

Mattiwaza's Oath

It is a document that for many archaeologists and historians, headed by Georges Dumezil, evidences the common origin and important relationships between the religions of the Indo-European peoples, which could indicate the existence of a probable proto-Indo-European religion prior to its diversification.

In the year 1907 AD. C. was discovered in Bogazkoy (the ancient Hattusa, capital of the Hittite Empire), an oath of fidelity to the emperor Suppiluliuma I, signed by his vassal Mattiwaza, king of Mitanni, to whom the former had replaced the throne and also granted his hand. of one of his daughters. These two fortunate events, restoration and wedding, must have occurred around 1340 B.C. C., and meant a respite -the last breath- for the kingdom of the Mitanians, already reduced by the Hittites to a state of humiliating prostration.

In the document, Mattiwaza promised to remain faithful to the Emperor of Hatti, putting as witnesses and guarantors not only several Babylonian and Syro-Hittite gods, but also some deities alien to the religions hitherto known in Asia Minor, and very familiar instead to ancient Indian literature, namely: Mitra, Varuna, Indra and the two Nasatía or Asuin (these last two a pair of twins).

It was not, therefore, a question of gods common to the Anatolian Indo-Europeans, the trunk to which the Hittites belonged, but of specific divinities of their most eastern branch, that of the Indo-European languages in satam (Indo-Iranian), to which the speakers of Sanskrit and Iranian corresponded.

One of the most agreed explanations among experts for this phenomenon is that, around the year 2000 B.C. C., the ancestors of the Mitanians separated from their Indo-Iranian brothers and headed towards Upper Mesopotamia, while the others did so towards India, where they would come to dominate the aboriginal population, despite being at a much higher stage of civilization. more advanced than its rulers, a fully urban civilization, owner of its own writing and even a refined art, particularly in the field of glyptic (the so-called Mohenjo Daro culture).

Theory of three functions

According to the French anthropologist Georges Dumezil, the bands of Aryan conquerors who spread from Syria to the Indus River during the second millennium BC had a mystical explanation of the world and society. Both this and the gods themselves were grouped and organized into three orders: magical and juridical sovereignty - priesthood - warrior force - military aristocracy -, and the producers or workers.

Mitra, Varuna, Indra and the two Nasatiya, the quintet of gods typical of the Mitanians by whom King Mattiwaza swears, are not just any, but mirror the strata or castes of Aryan society: Mitra and Varuna (the name of this, derived from the Indo-European Worvenos, is the same as that of Ouranós, Uranus, the firmament, of the Greeks) are the gods of the stratum of brahmanas or priests; Indra corresponds to the caste of warriors, the ksatriya and, finally, the two Nasatiya represent the third social class, that of the vais/a, herders, farmers and, in general, producers of all kinds.

Varuna and Mitra represented the antagonistic and complementary aspects of the spiritual world.

Varuna was the law, the requirement, the domain of the superior gods over the poor mortals, imposing destiny and duty, a strong and jealous god, in charge of punishing and judging men. He is a mysterious god, representing the underworld.

In contrast, Mitra is friendly, understanding with men. Although he is also a judge, he is the lawyer of men, a beneficent, reassuring god, inspiring acts and honest relationships, peaceful. He represents the life that his world gives to ours.

Indra, as the supreme warrior god, blesses the strength with which the soldier obtains victory, maintains the internal social order and defends the community from external aggressions, also allowing him to take possession of the territories and/or wealth of the enemies that delivers into your hands. A voracious champion, his weapon is lightning, with which he defeats demons and giants and saves the universe (a story that would be repeated over and over again in the different Indo-European mythologies, personifying Indra as Zeus in the case of the Hellenes, in Thor by the Norse, etc.).

Pantheons

The Indo-Europeans had a mythology based on triads. When the Indo-Europeans separated, their mythologies were mixed with those of the indigenous peoples they invaded. The names also varied. For example, Varuna became Ouranos, the Greek sky god. Indra, and upon arriving in Greece took the attributes of the son of the local mother goddess (Rhea), and became Zeus.

In the case of Italy, the Indo-Europeans began to worship Indra father and Indra mother, that is, Iun-piter and Iun-mater, which would become Iu-piter and Iunus (Jupiter and Juno). Indra's followers were the Indo-European gods called Marutes, armed with axes. The Latin Indo-Europeans made the Marutes one, Marut, Maris or Mars. This character became the god of war. In Greece the Indo-Europeans turned Marut or Maris into Ares.

Mithras, the sun god, survived under that name in India and Persia. In Greece he was supplanted by the local divinity Phoebus while in Italy he was abandoned by the Greco-Etruscan god Aplu, who became Apollo.

In Greece and Italy, before the arrival of the Indo-Europeans, mother goddesses were worshiped. The goddess of wisdom in Greece was Athena, turned into Athena. In Italy, among the Etruscans, the goddess of wisdom was Mnerva, where Minerva comes from.

In summary, the Indo-Europeans had a mythology with a probable common origin, according to the linguistic studies of Rasmus Christian Rask and Franz Bopp, and especially those of Georges Dumezil in comparative mythology. Pre-Indo-European Italy and Greece also had a similar matriarchal religion, due to geographical proximity. Greek and Roman mythologies diverged by adapting to different environments. However, as contacts between Greece and Rome increased, their mythologies were reunited. The resemblance is due more to a common origin than to the fact that one has been copied from the other.

Do they predate the idea of the Trinity?

The notable studies of the French anthropologist Georges Dumezil based on the mythology of the peoples considered Indo-Europeans, have emphasized the fact that many of them coincide in crowning their pantheon with a divine trinity. This is the case of the trinity made up of Esus, Tutatis and Taranis in the religion of the Celts, by Thor, Odin and Freya in the faith of the ancient Indo-European Nordic peoples, by Brahma, Vishnu and Shiva in the Indian Trimurti. Zeus, Poseidon and Hades in Greece or by the Greco-Roman Capitoline Triad, formed by Zeus/Jupiter, Hera/Juno and Athena/Minerva.

The predilection for that number also extended to society, divided into three castes: priests, warriors and workers ―respective roles of the main gods―. Curiously, the name of the number three is one of the few that is expressed ―together with concepts such as mother, night or star i>― similarly in known Indo-European languages.

The parallelism of the tripartite theological structure that shows the oldest Rome (and that the Romans recognize as such structure) regarding other non-Roma indo-European structures is surprising. The coincidence extends, even, to an important feature that we have already emphasized in Scandinavia and India. In the legend of the origins of Rome, Jupiter and Mars are given the entrance; it is the constitutive gods of the very idea of Rome and before the City: they create it, through Rhomulus, intervening with auspiciousness. On the contrary, it will be necessary a war, followed by reconciliation, so that the god Quirino, had by foreigners, will be admitted, at the same time that the Sabines, in the City and in the triad Iovis-Mars-Quirinus, in the same way that a war and a reconciliation were necessary for the Great Vanas, Njordr, Freyr and Freyja, to acquire the Quimuls nature of Asas and I mean, a man raised from Earth to Heaven. Thus, in one and another variant, while Jupiter and Mars are, forever, Roman gods and not mere adsciti, gods of full law and not men transformed into gods, the ultimate element, which completes the hierarchical triad, the god of agricultural prosperity, of the mass of the QuiritesOf the pax, it is conceived either as a foreign god, introduced at the time when the City is completed (and, thanks to the acquisition of women, acquires lasting condition), either as a divinized man, once his providential performance is completed: the heterogeneity, at least, of the third function in relation to the other two appears in all cases strongly marked.Georges Dumezil

Some authors outside the study of history, archeology and mythology, such as Alexander Hislop and Ralph Woodrow, have wanted to see in the Indo-European triads the continuity of an alleged original trinity that emerged in Babylon, presumably formed by Nimrod, Semiramis and Tammuz, but studies on history and comparative mythology, even those that are favorable to the idea of a common origin of the Indo-Europeans, deny it, especially since this supposed triad is made up of gods from different cultures and times, not all of them Indo-European, and with chronological distances of 800 years between their respective myths. These positions, and others such as the Zeitgeist documentary, use this argument more as an attack on the Trinitarian churches than as a scientific exposition.

Some common features

The gods common to all the Indo-European peoples are identified with a celestial body such as the Sun or the Moon, with a natural phenomenon or a part of the world: the Earth as Mother, the daytime Sky as Father, the divine Twins as the children, to Aurora as the daughter, the Moon; perhaps also Fire, but this element is not deified within many Indo-European peoples, who replace it with the home. From the Indo-European designation for God, *deywo, from a frequent opposition between gods and mortals, and from a common formula between Greece and India, Antoine Meillet concluded that the Indo-European gods were considered "celestial and luminous, immortal and givers of goods" and added to the celestial bodies and natural phenomena "the deified social facts", taking Mithras as an example, "pact of friendship".

Creation

These were much more pessimistic religions than the current ones, the beliefs of the Indo-Europeans were closely linked to cycles of death and birth. [citation required]

The gods were the human representation of the nature that surrounded the family. Like natural forces that they were, they lived and died. They participated in a cycle of eternal generations, the cycle of eternal return. [citation required]

Its priests considered the existence of an immovable principle, which governed life and destiny, that not even the gods could control, the future. All these divine forces arose from an immaterium, an unfathomable sea that had always existed, in which a Spirit flew above the water. This type of Creation myth occurred in Egypt, the Middle East and even in Greek religion, being common not only among the Indo-Europeans, but also among the Semites, even forming part of the great monotheistic religions. [citation required]

From the Spirit arises an organic mass, without form, which was separated by a god, Lord of the air and atmosphere. Another god remained in the stars, Lord of the Firmament, who would end up becoming an idle god, whose function passed into the background, not in importance but in pragmatic terms. Another goddess was the Earth, which was below the Firmament and the Air ―subjected to the male gods, as the Indo-European woman was strictly subjected to the man, the first Triad is identified in turn. From these materials the other gods arose. Here is an allusive text, extracted from the ancient Sumerian religion:

- In those days, in those archaic days,

- In those nights, in those archaic nights,

- In those years, in those old years...

- When Heaven had been separated from Earth,

- And when the Earth had been separated from Heaven...

- Having taken over An from Heaven,

- And Enlil of the Earth had taken over,

- And having given the hell to Youhkigal.

From the love affairs of these gods, other gods would be born, such as the Lord of the fields and fresh water, one of the wisest gods ―since he was the one who sustained the bases of their way of life, agricultural exploitation―. Under its domain we would have the Hell of Seven Locks, guarded by the Lord of the Seven Locks, a god (Charon, Hermes, Anubis, etc.) who accompanied the deceased to cross the Seven Courtyards or regions that they considered the world to consist of. afterlife, located under the earth or at the bottom of the sea, according to the various Indo-European cultures.

The Lords of Hell were a married couple, called Nergal and Ereshkigal (in Sumerian mythology), and Hades and Persephone (in Greek). This last goddess of the Averno, was considered sterile; Together with her husband, they were filthy gods who lived in dust, nothingness, which was where material life ended, the body of the deceased being destroyed by the tribulations of the Seven Regions of Hell for the purification of the soul and its metempsychosis. (reincarnation). Millennia later, many of the traits of the infernal gods would be attributed to Satan by Christianity.

The male god of the sun was extremely important, because it justified the monarchical and aristocratic lineages, and formed a triad with the Moon and sexuality, the main feminine divinity with the important function of blessing procreation ―in a time of extremely high mortality―, deified in Venus by the Hellenes, and in Ishtar by the Indo-Europeans of the Middle East, known in Phoenician as Astarte.

The omnipresence of the sacred

One of the conclusions of the comparative studies of Indo-European religions, and of these with later systems, is that in general it was considered that human dignity came from its continuity with the gods, culminating in man the nature emanated from the Immortals.

The continuity of divine nature extends to animals, plants and the whole of nature, also including minerals and inanimate objects. One of the ancient conceptions of the origin of humanity identifies the first human couple with plants. Many animals, particularly birds, have been considered the messengers of the gods. The streams of water are deified: they are gods in Greece and Rome, goddesses in India.

This universal sacralization is one of the main characteristics of Indo-European paganism. Its philosophical translation is pantheism.

The end of the world

Georges Dumezil, continuing his religious comparison, discovered very important parallels between the Nordic Ragnarök and the Hindu Twilight of the Gods.

According to the sagas and the skaldic poetry of the Nordic peoples, Loki and his creatures, the wolf Fenrir, the Midgard serpent and Hell, will pounce on the gods and appear as the victors. In the end, the Fenrir wolf shall open his gigantic snout, his upper jaw reaching for the sky. He is about to engulf the world, when Vidar emerges. One foot on the wolf's lower jaw, his arm reaching toward the upper, will destroy that monstrous muzzle. Thanks to him, a new world will live. His supreme god will be a son of Odin, Balder, the most beautiful and wisest being, of which our time was deprived by Loki's perfidy. So, thanks to Balder, justice will reign on Earth.

Georges Dumezil establishes an analogy between Vidar and Vishnu. On the day when, according to the Hindus, King Bali succeeded in conquering the world and expelling Indra, Visnu appeared in the form of a dwarf, and asked the victor to acquire the space that he could cover in three steps. Bali agreed. But Vishnu in those three steps covered the earth, the upper air and the sky, and thus, Indra regained his possession of the world.

Dumezil concludes, therefore, that the Indo-Europeans believed that thanks to gods like Vishnu or Vidar, they were not abandoned to monsters or Nothingness. That there was no despair in that Twilight of the Gods that the Indo-Europeans imagined. Well, on the contrary, it meant waiting for a better world. It was just a bad moment that had to be overcome before that future Eden.

The sky god

The word god (*deywos) has the same root as the word day (*dyew- ), because most cultures associate good with light and heaven, as well as evil with an underground and dark world, similar to the tomb that recalls the most painful experience, human temporality and the loss of loved ones. Despite his polytheism organized into triads, the first divinity of the Indo-Europeans, demiurge of the universe, was known by a common name: Dyeus, from which the current terms for god and day (in the languages heirs of the Indo-European), as well as the Latin name Iuppiter, the Greek Zeus and theos, the Sanskrit words dyaus (sky) and devah (god), Persian daeva (demon, by converting Indra and other gods into such by Zoroaster's monotheistic reform in the Avesta), Tig i>, day and Tuesday in English, etc. Etymologically, dyeus only meant 'luminous sky', later changing the attributes of its corresponding god among the various religions of the Indo-European peoples, nevertheless maintaining the name. The nominative of his Latin name, Iuppiter, composed of Dyeus and pater, coincides point for point with that of Dyaus pita of Sanskrit (and It has many similarities with the Homeric Greek expression, applied to Zeus: patér andrón de theón te (father of men and gods).

In the Vedic world, Dyaus pita is a divinity of very little relevance compared to Varuna, whose preferred domain is the sky (his Greek namesake, Ouranós, had to transfer to Zeus, instead, almost all his powers over the sky, leaving him as a mere personification of the firmament). On the contrary, both the Italic Iuppiter and the Greek Zeus not only maintained their rank as lords of the sky, but elevated it notably with other prerogatives.

This means that in prehistoric times, when the Indo-Europeans had not yet had experienced the diaspora of their groupings, Dyeus was nothing more than what his name indicates, a sky god who was recognized as having universal paternity. This was what remained the Dyaus of the Vedas. Instead, the ancestors of the Greeks and the Italics made Zeus and Iuppiter, respectively, something much greater: on the one hand, the ruler of gods and men: on the other, the god of lightning

The God of War

The extensive territorial expansion of the Indo-Europeans, which if at one extreme led them to India, at the other they reached Ireland and even Iceland, was verified largely by virtue of an institution that was maintained until fully fledged times. and which the Latins called ver sacrum (sacred spring). The name hides a very bloody reality. From time to time, under the imperative of overpopulation or famine, the young people of the same generation set out in search of land to live on, expelling their inhabitants from them or subduing them by force.

The tutelary genius of these expeditionary forces was called Marut-Mawrt, from which the Latin Mars (Mars) is derived, name of the god of war. The specific domain of this god almost everywhere was war as a means of defense for the community. His action was oriented, therefore, outwards, towards where the potential enemy had his headquarters. Hence, originally his place of worship was outside the city or town walls. His defensive action was capable of being applied to other threats, such as field pests. For this purpose, the Romans paraded in solemn procession around their fields the three animals ―the pig, the sheep and the bull―, the suovetaurilia, which made up the offering to the god.

Although in historical times the Romans did not make human sacrifices, they knew that many barbarian peoples sacrificed human victims to the god of war, and that after these the god's favorite offering was horses. At this point they were sticking to what appears to have been primitive ritual, closing the Mars station with the sacrifice of a horse.

The institution was still in force among the Indo-Europeans of pre-Roman Hispania. Strabo says of the Lusitanians: «When the victim falls [he probably refers to human victims] they make a first prediction by the fall of the corpse... They sacrifice goats to Ares, and also captives and horses». Proof of the antiquity of these rites is the correlation between the equus October of the Romans and the Vedic asvamedha, the horse sacrifice in honor of Indra. The sacrificer was to be a rashan (a king, the same word as Latin rex and Celtic rig), and the victim, a horse that had given speed tests in a race, the horse on the right of the winning chariot. The horse was free for a year, guarded by subjects of the king. If they failed to guard and defend it, and the horse fell into strange hands, the king could not be promoted among those of his rank. If, on the contrary, the horse passed the test, it was sacrificed according to a very complex ritual.

The position of the faithful before the gods

The negative cult, of respect for traditions, only implied the observance of a kind of social contract between the divinity and the community founded in his honor. A surprising feature for current archaeologists is that unlike some ancient religions, and the vast majority of current ones, in few Indo-European cultures men were observed prostrating themselves at the feet of the gods, face to the ground. On the contrary, a common feature of the sacred texts of Indo-European cultures was the camaraderie that some priests and warriors came to have with the gods (for example, Krisna and Arjuna in the Bhagavad-gita, Aeneas and Venus in the Aeneid). Even, in some contexts such as theater or crafts, it reached the point of mocking the gods, without fear of their wrath, unless the promises made to them were violated. Some castes come to be represented as equals before the gods, as was the case with the priests in Egypt and the warriors in the Nordic world, to the point of remaining standing, face to face and with the same height, and even using the common greeting Indo-European, arm raised.

The foreign gods

Due to the close ties that united the Indo-European community circles with their divinities, experts understand that they were local cults, without proselytizing spirits, that established a certain nationalism in their religion, which in principle entailed the exclusion of the cult to foreign gods, a custom that would be lost with the great migrations that the expansion of the empires entailed, since settlers and immigrants brought their gods with them to the newly discovered lands, creating a melting pot of cultures in the provincial capitals, let alone in the centers of power, the great cities head of the empires, such as Babylon, Persepolis, Athens or Rome.

If the worship of national gods is exclusive, foreign gods are considered as royal gods who protect foreigners, but can be tested in case of conflict. That is why sometimes foreign gods have been introduced into the set of Roman gods, for example.

However, there are also cases of interpretation of mythologies between conflicting Indo-European peoples, to better understand the adversary, preceding and confirming the works of Georges Dumezil: Gaius Julius Caesar does it in The Gallic War (6.7) for the Gallic gods, Tacitus in La Germania (9), for the Germanic gods: both are designated by names of Roman gods. This designation implies that the gods are the same and that their only difference is only in the linguistic order.

On the contrary, a true demonization of the gods of the Indian enemy is observed in a part of the ancient Iranian world, since they are those of their common ancestors: the Indo-Iranian denomination of the gods, *daiva (*deywo) becomes that of the demons. Many divine names have suffered the same fate: the Avesta knows a demon Indra, who bears the name of one of the greatest gods of Vedic India. One can see in these two extreme tendencies new elements of the opposite direction starting from an initial situation in which the gods of the foreigners are, by themselves, also foreigners, with whom one can deal but, therefore, without being able to adopt them.

The Priesthood

*bhlagh(s)men is the Indo-European word that linguists reconstruct as the basis of two others, so distant in space, as are those used by the Latins and by the Indians and Iranians to designate their respective priests, flāmen in the first case and brāhmaṇa (brahmán) in the second. The primitive rēx, the Latin king, has a priest at his service, like his Vedic equivalent, the rasha (rājaḥ) ―the so well-known word majarash (mahārājaḥ) is easily translated into Latin by magnus rēx) has a Brahmin as chaplain staff. The same relationship existed in Ireland between the rī, the king of the Irish Celts, and his own druid, although the name of the latter ―derived from that of the oak― did not keep relative to those of their Latin and Indo-Iranian counterparts.

According to Joseph Vendryes, those who maintained this conservative spirit that can be seen in the marginal areas of the Indo-European world were precisely the priests. Here is his explanation:

India and Iran, on the one hand, Italy, the Galia and the British islands, on the other, have in common preserved certain religious traditions, thanks to the fact that these countries are the only ones in the Indo-European realm in possessing priests' schools. Brahmanes, druids or pontiffs, priests of the vedism or of the ostrich, despite differences that jump much in sight, have, however, in common the maintenance of a unique tradition. These priestly organizations represent a ritual, a liturgy of sacrifice, in sum, a set of practices of those that are least renewed. But there is no liturgy or ritual without sacred objects whose names are guarded, without prayers repeated without changing anything in them. Hence, in the vocabulary, conservations of words that would not be explained otherwise.

Skeptical positions

The fact that authors such as Antoine Meillet and others find opposing views on essential issues of a religion, such as sacrifice or the priesthood (*bhlh2ghmen), even within the same people, has led them to seriously question the existence of the original Indo-European religion. For example, regarding sacrifices, in ancient Greece, some cities considered that the sacrifice invited the gods to participate in the ceremonies, while for others the fire raised the votive offering to the god to whom it was dedicated, who delighted with the smoke

These historians, prehistorians and archaeologists consider that the works of Dumezil and others have failed to demonstrate a unity or a common and/or equivalent origin of the gods, priests and cults of the Indo-European peoples. Based on this, they refute the idea of the identification of the Indian Brahmin with the Roman flāmen (both derived from the term *bh lh2ghmen 'priest') and question the identification between the Indian horse sacrifice and the Roman October equus.

Among these authors, not only are the detractors of Georges Dumezil, but also Edgar C. Palome, who in his work Das pferd in der religion eurasischen volker, die indogermanen und das yerrf becomes I echo the criticisms above.

These authors acknowledge, however, the genius of Dumezil in his Theory of the three functions, which for them certainly represents a considerable advance in the knowledge of the Indo-European tradition, parallel to the reconstructed ceremonial. But this hypothesis is represented differently in the various religions, and mainly in the pantheons of each culture. If a good part of the Indo-Iranian and Germanic divinities can be perfectly fitted into this framework, it is not so easy to do so in the case of the Greek and Celtic Olympians and, in the case of the Roman Olympians, the three functions are manifested almost exclusively in the "archaic triad: Jupiter, Mars and Quirino".

Eschatological diversity

One of the problems faced by scholars of Indo-European polytheistic religions is that they did not have proper dogmas about the world beyond the grave. Everything that concerns the nature of the gods or their number, the origin of the world, its evolution, the ultimate ends of man, was elevated to myth. Truth or Harmony (*h2rt(h)-, > Latin ar(t)-s 'art', > Greek arithmos 'number'), which was the central value of the Indo-European world, concerns man's behavior in this world, fidelity to his own, to the given word and not to the version of mythology, of cosmology, of the cosmogony that man adopted or invented.

Formulated by Brahmanical India, the first two possibilities according to the widely spread conception of the «three ways beyond the grave», to remain for glory (the «path of the gods»), to survive by descent (the «path of the parents"), and the path of mystery, implied the absence of survival for those who did not leave behind them memories, posterity, or offspring, also excluding individual survival. But this logical consequence contradicted the feeling of those who conceived the Hereafter as an extension of terrestrial existence, deeply rooted in the Indo-European world, as shown by the funerary goods that provide the deceased with what they may need in the "other life".. For example, in the Brijad-araniaka-upanishad , the sage Iagña Valkia scandalizes his favorite wife when he tells her that there is no consciousness after death.

This conception, which was that of Homeric Greece, was strange or unsatisfactory for those who wanted a conscious survival, and who found in the mysteries ―cult of Dionysus, Mithraism, Orphism, Pythagoreanism, Platonism and Neoplatonism―, and more Late, during the final period, in the great religions, foreign to the Indo-European world - Buddhism, Christianity, Islam - a response to their wishes, which could also perhaps have been the main cause of the dissolution of that world.

Contenido relacionado

1004

549

1390