Proto-Indo-European language

Proto-Indo-European (or pIE) is the hypothetical proto-language, a reconstructed mother tongue, which would have given rise to the Indo-European languages. The linguistic reconstruction is carried out on the evidence of those considered to be descendant Indo-European languages, which survived it, by means of the comparative method.

Technically, the name Proto-Indo-European is reserved to designate the earliest reconstruction of Common Indo-European. The fragmentation of IE (Indo-European) around 3000 BC is accepted. C. or a little later. This linguistic reconstruction is carried out by means of the so-called comparative method based on the evidence of similarities between Sanskrit, classical Greek, Latin, Germanic and other Indo-European languages.

Proto-Indo-European should not be confused with Pre-Proto-Indo-European, partially accessible by internal reconstruction and which would have been the ancestor of Proto-Indo-European proper.

Possibly the people who spoke that language expanded demographically, culturally or militarily and ended up absorbing other ethnic groups that previously spoke different languages. Subsequently, the linguistic subgroups derived from the common mother tongue would be formed.

Dialectal division

The hypothesized Proto-Indo-European language is dated between 3500 and 2500 BCE. C. and would have been made up of closely related dialectal varieties. Geographical variations, increased over time, produced a remarkable differentiation that, over time, would result in the very different Indo-European languages today. The knowledge that we have of this language is due to the comparative method and its modern development, historical linguistics. These methods allow a fairly rough reconstruction of many features of Proto-Indo-European; however, they are not able to clearly elucidate the problem of dialectal variation. In fact, the initial dialectal differentiation of Proto-Indo-European is very difficult to know and has been a controversial subject. It is considered that the current groupings of the Indo-European languages must somehow reflect the initial differentiation of Proto-Indo-European.

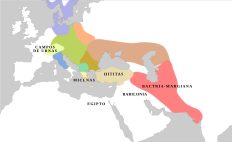

The early Indo-European civilization, living between the northern Caucasus and the northern Caspian Sea, is believed to have developed during the 4th millennium BCE. c.

Between the years 4000 and 3500 B.C. C., their first migratory movements took place towards the current territories of Ukraine, Romania, the Balkans and eastern Hungary. In a second wave (between the years 3500 and 3000 BC), the primitive Indo-European peoples would have settled in central and northern Europe, the Balkan region, Anatolia and northern Iran. Finally, there was their displacement towards Greece and the eastern Mediterranean area. During the course of their expansion, the Indo-Europeans came into contact with other populations, whose language was replaced by that of the conquerors.

Major Subgroups

Although the intermediate level phylogenetic groups are clear (Italic, Tocharian, Anatolian, Hellenic, Germanic, Indo-Iranian, etc), there is no agreement on the exact relationship between these groups and on what would be a suitable phylogenetic tree for the family Indo-European. Currently there are two widely discussed models: the Gray-Atkinson tree (The 'New Zealand' family tree, 2003) and the Ringe-Warnow-Taylor tree (The 'Pennsylvania' family tree, 2002). The former is strictly based on shared and substituted lexicon, while the latter is based on phonological and morphological isoglosses. Although both classifications have some common points, they also differ in important ways in other details. Some of the minimum units that both trees coincide in grouping are:

- anatolio

- Tocario

- Greek-Armenian

- Albanian

- Balto-eslavo

- indo-iranio

- German

- Iole-cell

When trying to group those groups, according to various criteria, different trees emerge, so the high-level relationships, which presumably should give information about the original Indo-European dialects, do not seem reconstructable. Another universal coincidence across all classifications is that Anatolian and Tocharian were the first languages to break away from the common stock (curiously these two language groups were not properly known to Indo-Europeans of the XIX).

Satem/Centum

In the 19th century, August Schleicher and other Indo-Europeans considered that the fundamental division was given by an isogloss that divided the family into two different groups: the Eastern Indo-European languages or satem languages and the Western languages or centum languages, according to the evolution of the phoneme /*kj /: in the first languages there would be palatalization of this phoneme in /*š/ (and later in some languages it would change to [ʃ], [ɕ] or [s]), while in the latter it would remain as velar. The most publicized example of this division, and which gives its name to the division itself, is the change observed in the Indo-European word *kntom 'hundred', which in Sanskrit is śatam [ɕa'təm] and in Latin is centum ['kentum], while in Avestan the word became satem [sa&# 39;təm]. That is why the Indo-European languages have been classified either by belonging to the western branch (of the centum), or to the eastern branch (of the satem).

Certain language families of Indo-European origin (Albanian, Armenian, Indo-Iranian, Slavic, and partly Baltic) are satem languages. However, this feature is now considered marginal and the result of a relatively late diffusion of an isogloss that, with different degrees of completeness, mainly affected oriental languages. However, eastern languages such as Tocharian do not show palatalization, suggesting that this palatalization played no role in older Indo-European. In addition, other distinctive features are considered to be more important within the Indo-European family.

The first division of the Indo-European languages is into the Danubian and Norse groups.

Old European

Old European was initially proposed, assuming that there was a precursor language spoken in European territory, which by diversification gave rise to the following groups:

- Greek (divided in aqueo, jonio—and the mixture of both eolio—dorio, Greek of the northwest and others),

- italic (Latin origin and nearby languages, sahelic, osco-umbro and others),

- Celtic (origin of Breton, Britan, Gallo and others) and

- Germanic (divided in turn in the Nordic branch [origin of Norwegian, Swedish, Danish and others], the Gothic branch and the German branch, origin of German, English, Dutch and others).

However, these languages are almost certainly not a phylogenetically valid unit, since, for example, the Greek branch shows more closeness to the Armenian branch than to any other current group of Indo-European (the closeness of Greek to some Paleobalkanic languages is not well known, but it could be similar to the one it saves with Armenian).

The Indo-European “people”

Despite some unscientific uses of the word, there is no scientific evidence for an Indo-European ethnicity. However, during the 19th century and the first half of the 20th century, it was common to use the term to designate a supposed race, called the Aryan race. The word "Aryan" comes from the Sanskrit arya of the Vedic texts, who presumably brought the Indo-European languages to Hindustan. According to the assumptions of some authors of the xix century, this Aryan race was characterized by white skin and light hair [ citation required]. With the rise of National Socialism to power, the term reached higher levels of manipulation. At the end of World War II, scholars began to consider limiting the use of the term to the strictly linguistic.

The term "Indo-European" is only correctly defined in linguistic contexts, and it is assumed that there was some kind of ethnic group or ethnic group that spoke Indo-European languages. However, the archaeological identification of some ancient peoples with Indo-European ethnicities remains controversial.

Reconstruction and description of the pIE

Although Proto-Indo-European is a dead language not attested directly in writing, it is possible to reconstruct a large part of its phonology and grammar from the linguistic evidence of languages related to each other through the so-called comparative method. Currently, there is quite a consensus on the linguistic reconstruction carried out on the Indo-European (IE) languages, allowing the reconstruction of various strata. The most recent stratum, called IE III or Classical Proto-Indo-European or Brugmanian, which would be the direct source of almost all Indo-European languages, except Anatolian languages, and is the most widely treated in the works. It has been pointed out that the comparison of IE III and the Anatolian languages allows to partially reconstruct a somewhat older language called IE II with characteristics notoriously different from those of IE III. Before IE II it would be preflexional Indo-European or IE I.

The most easily reconstructible part is the lexical level and the phonology of the language. Also, it is possible to largely reconstruct nominal and verbal morphology, from the evidence of later Indo-European languages. Every reconstructed lexical or grammatical element is called a protoform —hence the name "proto-Indo-European"—, which is usually preceded by an asterisk to indicate that it is not really attested, but that it is supposed to be so.

Phonological Inventory

The phonological inventory of Proto-Indo-European was first reconstructed with certain guarantees in the second half of the 19th century. Since then some revisions of the number of phonemes and the realization of the same have been proposed. The rebuilt system is as follows:

| Labial | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Labio-velar | Gloss | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Occlusive | sorda | ♪ | ♪ | * | ♪ | *kw | *h1 (pool) |

| Sonora | ♪ | ♪ | * | ♪ | ♪ | ||

| vacuum | ♪bh | ♪ dh | * | ♪ | *gwh | ||

| Fridge | ♪ | ♪ | *h2 | ||||

| Sonorating | ♪ | ♪ | ♪ | ||||

| Nasal | ♪ | ♪ | |||||

In modern reconstructions there are no serious discrepancies regarding the number of stops, although their precise articulation is doubtful. Traditionally it had been assumed that their main allophone is the one shown in the table, but the glottal hypothesis, proposed to explain the low frequency of /*b/ argues that /*p, *b, *bʰ/ of the traditional reconstruction would have been articulated as: /*p[h], *pʼ, * b[h]/ respectively (and similarly for the alveolar, palatalized velar, flat velar, and labiovelar series). It has even been proposed that the difference between what were traditionally called voiceless, voiced, and aspirated stops could have been based on more complex phonations than the voiceless/voiced difference.

There have also been arguments against the reconstruction of two series: palatalized velars /*kʲ, *gʲ, *gʲʰ/ and flat velars /*k, *g, *gʰ/, instead of one. It seems that the first series occurs overwhelmingly in palatal settings, and it could be that, even if there is an allophonic difference in some dialects, the two series may not be phonemes apart.

Finally, there are three laryngeal phonemes /*h₁, *h₂, *h₃/ whose reconstruction is outside beyond doubt, on the basis of vowel alternations and its direct testimony in Anatolian. However, its phonetic realization is highly speculative, being generally considered phonemes whose point of articulation is in the posterior part of the buccal tract. Some authors reconstruct a greater number of laryngeal phonemes, although their phonological distinctiveness with respect to the three classic laryngeals is highly disputed.

Regarding vowels, late non-Anatolian Indo-European (sometimes called pIE III or Late Indo-European) distinguished between long and short vowels. Usually the system is reconstructed as formed by the vowels /*i, *e, *a, *o, *u; *ī, *ē, *ā, *ō, *ū/. However, in an earlier state the system could have consisted of only three vowels /*e, *a, *o/ initially being the sounds [i, u] allophonic variants in syllable nucleus position of the resonants /*y, *w/, respectively. The long vowels could all be effects of morphological lengthening or vowel + laryngeal sequences: *ī< *iH, *ē < *eh₁, *ā< *ah ~ eh₂, *ō< *oH ~ eh₃, *ū< *uH.

Each Proto-Indo-European word had a single stressed syllable that received the greatest tonal load. It was also an element with phonematic value, that is, it was used to indicate the different grammatical categories of words (in a similar way to what currently happens in English, which has doublets of the type increase [noun: 'increase'] / increase [verb: 'increase'] rebel [noun: 'rebel'] / rebel [verb: 'to rebel']). For example, in the nominal declension of some nouns such as *pṓd-s 'foot', the nominative and accusative took the prosodic accent on the root, while the genitive, dative and instrumental did. they had the suffix *ped-SÚF. A similar phenomenon occurred with verbs.

Phonetic Laws

In the study of the evolution of ancient Indo-European, the determination of phonetic laws such as the Grimm and Verner laws, which established a constant phonetic correspondence between some phonemes of the different languages of the family, had special relevance.

A basic principle that was established then is that of the constancy of phonetic change, which establishes —in a simplified way— that in the transition from the mother language to a daughter language, if a sound or series of sounds changes, that change occurs in all words in which it occurs. Thus, for example, we know that the Dutch verb hebben (< pIE *keh₂p-) is not a cognate of the Spanish haber (< lat. habēre < pIE *gʰh₁bʰ-), but from caber, since, according to what we call Grimm's law, the phoneme /k Indo-European / becomes /h/ in Germanic languages (such as Dutch), but remains as /k/ in Latin and Greek.

The following table shows the main phonetic correspondences between the oldest Indo-European languages of each branch as regards the plosive sounds:

| Occlusive | pIE | Ancient Greek | Latin | Irishman | Gothic | Armenian Classic | Lithuanian | Slavic. | Tocario | Hit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| the lips | *p, (*b), *bh | p, (b), ph | p, (b), f/b | Ø, (b), b | f/v, (p), b | h/v, (p), b/v | p, (b), b | p, (b), bh | p, p, p | p/b, p/b, p/b |

| Alveolar | *t, d, dh | t, d, th | d, f/d | d, d | CHE/d, t, d | t/y, d, d | d, d | dh | t, t, t | t/d, t/d, t/d |

| palatalized guards | *kj, *gj, *gjh | k, g, kh | c, g, f/g/h | c, g, g | h/g, k, g | s, c, j/z | š, ž, ž | s, z, z | k/ś, k/ś, k/ś | k/g, k/g, k/g |

| monitoring | *k, *g, * | k, g, kh | c, g, h/g | c, g, g | h/g, k, g | k`, k, g | k, g, g | k, g, g | k/ś, k/ś, k/ś | k/g, k/g, k/g |

| lipstick | *kw, *gw, *gwh | p/t, b/d, ph/th | what, gu/u, f/gu | c, b, g | hw/w, q, gw/w | k/ç, g/j | k, g, g | k/č, g/ž, g/ž | k/ś, k/ś, k/ś | kw, kw, kw |

Apophony

A characteristic feature of Proto-Indo-European is the system of vowel alternations known as apophony, consisting of an ordered series of vowel changes that served to express different grammatical functions (as occurs in modern English with some irregular verbs, such as write 'I write, -e' and its past tense wrote 'I wrote, -ió'). Apophony affected the vowels e and o in Proto-Indo-European. The basic form was always e, although this vowel could appear as o in certain phonetic contexts, while in others both sounds could disappear entirely. On this basis, in Indo-European linguistics we speak of forms that show, respectively, the degree e (or full degree), the degree o and the degree zero: it is what is known as qualitative apophony. The vowels e and o could also appear as their long correlates ē and ō, in which case one speaks of elongated degree: it is what is known as quantitative apophony.

The following example serves to perfectly illustrate all of the above: the Indo-European root *pṓd-s (gen. pḗd-s, ac. pód-m ) 'pie' appears in the degree e in its Latin reflex ped- (from which Spanish pedal comes), while which was preserved in the degree o in the corresponding Greek root pod- (as in podology). The zero degree *pd-, without any vowels, is attested in Sanskrit, and the lengthened degree o in the Germanic root *fōt- (in English foot 'foot'), which comes from the protoform *pōd-. The joint action of qualitative and quantitative apophony represented an important mechanism of morphological characterization in Indo-European, since it was used to represent grammatical categories in their different inflectional forms.

Nominal bending

Proto-Indo-European was an inflectional language, like the vast majority of later Indeo-European languages, and inflection affected nouns, adjectives, pronouns, and verbs. Specifically, the existence of nominal inflection, also called declension, means that a noun has a specific ending according to its grammatical or syntactic function in the sentence. These endings depend on the theme or paradigm to which the name or adjective belongs, and in Indo-European they basically depend on the ending of the root or lexeme. All the declension paradigms have certain similarities and are easily reconstructable from the Indo-European languages attested in writing.

Nominal inflection basically used endings or special endings to modify nouns and adjectives (although it also made some use of vowel alternations). In the name the categories expressed by the inflection are those of case and number. Most modern Indo-European languages, however, have lost much of this morphological complexity, present in Proto-Indo-European attested in the oldest Indo-European languages for which we have records.

Brugman's reconstruction from the classical Indo-European languages, excluding Anatolian, suggested that the number of cases could be as large as eight, that the language had three grammatical genders (masculine, feminine, and neuter). This stage roughly reconstructed by Brugman is sometimes referred to as pIE-III. However, the decipherment of Anatolian cast doubt on some aspects of this reconstruction, conjecturing that there could have been a stage, called pIE-II, in which the genders were not divided into masculine/feminine/neuter, but into animate/inanimate, in the case of a language of active linguistic typology.

Some examples of morphology: the noun *ḱr̥h₂wós 'deer' is formed by the root *ḱerh₂- 'horn', the nominal suffix -wó- and the casual singular nominative ending -s. The root contains the basic semantic core (the underlying idea that motivates the meaning of the word), while the suffix serves to indicate the morphological category to which it belongs, and the ending provides more detailed grammatical information based on the syntactic function of the word.. Thus, a single root like *preḱ- 'ask' can, depending on the suffix attached to it, form a verb in degree zero *pr̥sḱéti 'ask, to ask' (> Latin pōscere), a noun in the grade e *preḱ- 'prayer' (lat. prex, gen. precis) or an adjective in the degree o *proḱ-o- 'suitor' (lat. procus).

Verbal inflection

Before the discovery and proper understanding of Hittite, several Indo-Europeans had proposed a preliminary model of the categories and conjugation of Proto-Indo-European verbs, now known as the "Indo-Greek model" because Sanskrit and Ancient Greek are the languages that they showed a higher degree of retention or conservatism with respect to the reconstructed system. In this system, which could have been after pIE III, there is apparently a system of two voices (active and medio-passive), four modes (indicative, subjunctive, optative and imperative) and three tenses (present, aorist and perfect). However, this last grammatical accident did not represent a direct and explicit mark of the Indo-European verb (a fact that was generalized in all the languages that derived from it), since what was actually established were aspectual relationships, based on the type of activity expressed by the verb (momentary, continuous, iterative, etc.).

Verb inflection uses almost exclusively suffixes, with two exceptions: the augment *e- in the imperfect (preserved only in Greek: leípō (< *leikʷ-ō) - élipon (< *e-likʷ-), Armenian and Indo-Iranian) and the infix *-n-, attested in Latin vīncō 'I conquered' - vīcī 'I conquered', linquō 'left [behind]' (< *li-n-kʷ-) - lictus 'left [behind]' (< *likʷ-tos) and from the same Sanskrit root riṇakti (< *li-ne-kʷ-) 'leave [behind]' - rikthās. The rest of the prefixes found in Indo-European are always derivative prefixes.

In addition, the verb, like practically all modern Indo-European languages, had marks of person (first, second and third) and number (singular, plural and dual).

Syntax

Some authors have argued that the syntax, being highly compositional, is one of the parts of the grammar that can present greater temporal variation and that based on the existing evidence it would not be possible to reconstruct the syntax of the pIE. Although most ancient languages have strong statistical evidence in favor of SOV order, that is not definitive proof of syntactic order. Some nominal expressions fossilized in lexical form, such as despot < *déms-pot- 'lord of the house', suggest that the genitive precedes the noun, in this case the head of the noun phrase being placed at the end.

Although the reconstruction of syntactic order is complex, other aspects, such as the nature of negation, coordination marking, and subordination, can be better reconstructed.

Lexicon

The methods of historical linguistics have made it possible to identify a large number of Indo-European roots, and dictionaries now exist with several thousand terms. However, although it is easy to identify roots from the comparison of Indo-European languages and reconstruct their original form, it is more difficult to ensure that a certain lexical form (root + derivational morphemes + inflectional morphemes) actually existed in Indo-European, since the details Specifics of Indo-European lexical morphology are not easily reconstructable from comparison.

The main mechanism for word formation in Indo-European was the composition or combination of two different words to form a single word.

Schleicher's fable

In 1868, the German philologist August Schleicher created an artificial text composed in the reconstructed Proto-Indo-European (PIE) language. It's called The Sheep and the Horses.

Rebuildable Stadiums

The linguistic reconstruction of the best documented Indo-European languages already allowed in the XIX century to reconstruct with enough approximation the phonology and grammar from ancient Indo-Europe. This first reconstruction of Newer Indo-European is known as pIE-III. The internal reconstruction on this first reconstruction makes it possible to reconstruct other older stages, pIE-II and pIE-I.

Pre-Proto-Indo-European stage pIE-II is the language from which Late Proto-Indo-European, or pIE-III, was formed. For reasons of closeness in time, Late Proto-Indo-European is better known and reconstructible in greater detail than Pre-Proto-Indo-European pIE-II. pIE-II is also a synthetic language, whose inflection is non-thematic, compared to pIE-III, where thematic inflection predominates and non-thematic inflection is secondary. Prior to pIE-II is pIE-I, which is a more insulating tongue with possibly much reduced flexion. The main characteristics of these three stadiums would be:

- IE III (classic indoeuropeo), which has a fully developed morphology similar to that of the Greek and Sanskrit, gender distinctions (male, female, neutral) and in which the larynx could have disappeared or were in the process of disappearance.

- IE II (monothematic preindoeuropeo), which would not have all the times and modes found in languages such as Greek, Sanskrit and Latin, and would lack thematic bending as found in most of the indo-European languages. EI-II would have full effect on the larynx and gender distinctions of animated/inanimated type, similar to what is in the Hittite language and other languages of the anatoly group.

- IE I would be an imperfectly known and deductible stage of arcaisms found in all branches. In this stage, much of the characteristics of the classical indo-European would not exist, and the IE-I would be a relatively insulating language.

Relationship with other languages

As far as it is accessible, Pre-Proto-Indo-European (pIE I) turns out to be a language with considerably less morphology than Late Indo-European. Judging from the data from the Anatolian Indo-European languages, Pre-Proto-Indo-European would have lacked grammatical gender and the extensive morphological case system exhibited by languages such as Greek, Sanskrit, or Latin, and which would go back to more recent Indo-European. Some authors, such as Rodríguez Adrados, have come to affirm that the absence of certain categories in Anatolian languages, such as Hittite, are a reflection of what pre-Proto-Indo-European was like (alternatively, other authors explain the absence of these categories in Anatolian as a loss to from a morphologically "richer" system). It has been estimated that Pre-Proto-Indo-European began to be spoken around 5000 B.C. C. and up to 3000 B.C. C., in which the Anatolian branch was separated.

Additional hypotheses, quite controversial, propose that Pre-Proto-Indo-European would come from older proto-languages such as Protosapiens, from which all the languages of the world would derive, Proto-Borean, from which all the languages of Eurasia, America, North Africa, Polynesia and Micronesia, the Protonostrastic from which the Afroasiatic, Dravidian, Kartvelian, Amerindian and ultimately Proto-Eurasian languages would derive, together with the Altaic, Eskimo-Aleut, Chukoto-Kamchatka, Thyrsenic languages, possibly passing through a Proto-Indouralic from which the languages would also derive Uralics and probably Yucaguiras.

However, due to the enormous distance in time that these hypothetical proto-languages would have been spoken, the number of convincing possible cognates that could be assembled is much smaller than for Proto-Indo-European. It is this paucity of reliable data that makes the theory controversial, and what has led some linguists to argue that, even if these protolanguages or superfamilies did exist, the evidence would be so small that we cannot ensure their existence using the methods normal for the comparative method due to the great temporal depth.

Contenido relacionado

Roman Jakobson

Purépecha language

Ergative case