Printing

Printing is a mechanical method used to reproduce texts and images on paper, vellum, cloth or other material. In its classic form, it consists of applying an ink, generally oily, on metallic pieces (types) to transfer or record it by pressure. Although it began as a traditional method, its implementation in the mid-XV century brought about a gigantic cultural revolution.

More modernly, the evolution of various technologies has given rise to different printing and reproduction methods, such as flexography, screen printing, rotogravure, high engraving, electrolytic photography, photolithography, lithography, offset printing, xerography and digital methods.

History

The Romans already had seals that printed texts or images on clay objects around the year 440 B.C. C. and 430 B.C. c.

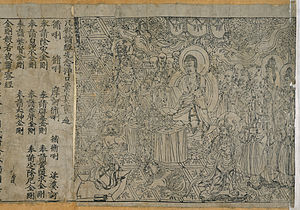

Between 1041 and 1048, Bi Sheng invented the first movable-type printing system in China, where a type of rice paper already existed, using complex pieces of porcelain on which Chinese characters were carved. This was a very laborious procedure due to the immense number of characters or letters of Chinese writing. Later, in 1234, in present-day Korea, craftsmen during the Koryo dynasty, aware of Chinese advances with movable type, created a set of metal movable type, which anticipated modern printing but rarely used it.

Before the appearance of the printing press, books were distributed exclusively through handwritten copies, made by copyists, many of whom were monks or friars dedicated entirely to prayer and manual copying of books, commissioned by the clergy themselves. or of kings and nobles. Illustrations and capital letters were decorative and artistic products that were generally made by artisans other than the copyist. For this reason, the production of a handwritten book was a process that could last years, since each one had to pass through the hands of copyists, illustrators and bookbinders. And all this, to produce a single and simple copy.

The most direct antecedent of the modern printing press is the xylography, which during the Middle Ages was used in Europe to publish advertising or political pamphlets, labels and works of few pages. Woodcut requires hand carving the text or image into a hollow on a wooden tablet, which is a laborious craft. Then the tablet was impregnated with black, blue or red ink (only those colors existed), it was applied to the paper and the ink was fixed with a roller. The wear of the wood was considerable, so that many copies could not be made with the same mold.

History of modern printing

Previous techniques

A set of techniques was necessary for the printing press to be created and function the way Gutenberg envisioned it. Only when these productive processes reached their maturity could the printing press make use of them. For example, without the large-scale production of paper, the printing press was pointless, since the use of parchment was too onerous. Gutenberg's crucial contribution was to unite these diverse elements, add new ones and combine it all in a complete, functional, simple and economical system.

Among these production techniques or processes we have: paper manufacturing, ink development, metal alloys, presses for agricultural use and wood block printing (or xylography).

- Paper

- The Arabs had learned and used the Chinese art of its manufacture, developed it widely in the Muslim world and brought it to Spain and southern Italy. The mediaeval paper manufacturers in Europe mechanized their manufacturing, using water-powered factories, whose first evidence is certain of 1282. This allowed a massive expansion of production and replaced the complicated craftsmanship characteristic of the manufacture of Chinese and Muslim paper. Paper manufacturing centres began to multiply at the end of the centuryXIII in Italy, reducing the price of paper to a sixth part of the scroll and then falling further.

- The Tinta

- In Europe at the end of the centuryXIII Inks were produced for writing or dyeing of fabrics, but they were water-based and therefore too liquid to print. Xilography, with wood moulds, used more adaptable inks, but not the type that the metal requires.

- Metals

- There was also in the time the knowledge to perform a wide range of metal alloys with different use and Gutenberg knew them, as it was goldsmith.

- The press

- The different types of screw presses, which allow direct pressure on a fixed plane, were already known at the Gutenberg era and used for a wide range of tasks. Created towards the centuryId. C., the Romans used them normally in agricultural production, to press grapes and make wine; or olives and make oil. Gutenberg may also have been inspired by these presses, which had spread throughout Germany since the end of the century.XIVand they worked with the same mechanical principles.

- Mobile types

- This concept already existed in Europe before the centuryXV. Sporadic evidence indicates that the typographical principle was known, i.e. the idea of creating a text by reusing individual characters, as it had been appearing since the centuryXII and possibly before (the oldest known application goes back to the Festo disk). The known examples range from the printing of mobile types in China during the Song dynasty, passing through Korea during the Goryeo dynasty, where the printing technology of mobile types in metal was developed in 1234, to Germany, England and Italy (Pellegrino II altarpiece). However, the various techniques used (printing, drilling and assembling of individual letters) did not have the refinement and efficiency to print large amounts of text with good quality. Tsuen-Hsuin and Needham, as well as Briggs and Burke, suggest that the printing of mobile types in China and Korea was rarely employed.

- The codex

- Another factor conducive to printing was the codex format, which the books had already adopted in the Roman era. Considered the most important advance in the history of the book before the printing press, at the beginning of the Middle Ages (about 500 AD) the codex had completely replaced the old format in which pieces of parchment or papyrus united are written and then rolled and unrolled to read them. The codex is a collection of sheets of any material (papel, parchment or papyrus) with one or more folds, joined by the back or loin, and generally protected by covers. The codex has considerable practical advantages over the roll format: it is more convenient to read (passing pages), more compact, less expensive, and both the reverse and the back of the sheet can be used to write or print, unlike the roll.

Gutenberg's Work

The printing press had many antecedents, in the different seals and inscriptions invented by ancient cultures to manage their bureaucracy or reproduce ceremonial illustrations. The Chinese, for example, who had made rice paper, invented a porcelain system in the 11th century that allowed its characters to be reproduced from porcelain moulds. But the modern printing press as such arose in about 1440 at the hands of Johannes Gutenberg. Based on these techniques and production processes, Gutenberg set about creating a machine capable of making several copies of a book (such as the Bible) at the same time in less than half the time it took to copy one the fastest copyists and that they did not differ at all from the manuscripts. Here you can see how perfectionist Gutenberg was, who began his challenge without being aware of what his invention was going to represent for the future of humanity.

- Creation of mobile types

- The first challenge was to create individual letters that could be used separately to print texts: in this is a mobile type.

- Gutenberg started by making iron marks in which he manually carved a letter with the design and source he wanted. To print a book, it needed to make about 270 points, each with a different letter, number or sign; or the same graph, but in different sizes. Then with a spleen he hit the puncture against a soft metal, like copper, creating the call matrixwhich has the image in low relief and inverted from the letter. The matrix allowed to manufacture hundreds of “a” or “A”, all identical to each other; and the times that were necessary. A puncture game allowed to create many matrices, which in turn could manufacture hundreds or thousands of mobile types.

- Then Gutenberg put the matrix already acuna at the end of a hard metal mould, where it emptied a alloy of molten metal, which allowed it to create a metallic bar at whose end was the letter that would be used to print: the mobile type.

- Gutenberg had now to create a alloy of metals that would allow him to quickly and at low prices melt his mobile types. After many trials and errors, he managed to give with a alloy based on lead, tin and antimony, which adapts so well to print purposes, which is still used today. The advantages of this alloy are two: Its components are abundant and cheap; and they melt at low temperatures, about 285 degrees centigrade.

- The mass production of mobile types was achieved through the two key inventions of Gutenberg: metal alloy and mould to justify the matrices. Before him there was nothing like it.

- It is enough to imagine how many letters "a" or "D" can be needed to print a whole page of any book, to understand the enormous amount of mobile types necessary for a printing press to be operational. The Latin alphabet has a great advantage in this process because, unlike the Chinese ideographic writing system, it allows to represent any text with a theoretical minimum of only about three dozen different signs. "Gutenberg's invention maximized the degree of abstraction in the representation of the forms of language offered by the alphabet and the Western forms of writing that were current in the 15th century".

- The galley

- To make a page, you should write the text, lyrics by letter with the mobile types, finding them in a kind of wooden box, generally called galera. It is a matter of keeping the letters still, until after the leaves are printed. It is necessary to consider how difficult to write with the types, since these have the reversed letters, or the other way around; like those of the typewriters, based on the same principle. This whole mechanism must have been created from nothing by Gutenberg, because it did not exist before.

- The inks

- Gutenberg also created a specific type of ink for printing. After much experimentation, he managed to overcome the difficulties caused by traditional water-based inks, which when wet the paper, break it or prevent printing both sides of each leaf. It found the formula for an oil-based ink, suitable for high quality printing with metal types.

- The press

- Once the mobile types with which to print are made, pressure should be applied for the ink to record the text on the leaves. Gutenberg built an old grape press to perform the printing process. As the print imposed a few demands on the screw press very different from that of the pressing of grapes or olives, Gutenberg adapted it so that the pressure force exerted by the platinum on the paper was applied in a uniform and elastic manner, so as not to break or over-emphasize the paper. To accelerate the printing process, he introduced a mobile table, with a flat surface on which the leaves could be changed quickly.

- The press itselfconsists of the following parts:

- A long table, one of whose halves approximately has a sliding section, called a stone base.

- On the basis of stone, the set of mobile types with text, or form, are put upside down.

- An abatible mechanism, or frame, which allows to locate the paper, close it and then put it directly above the form. The frame is a kind of diptic, with leaves that can be opened and closed, within which the paper is placed. Once the pressure is applied, this mechanism is removed from the bottom of the press, the frame is opened and the paper already printed is removed.

- The pressure mechanism, or the press itself, is placed on one half of the table. Gutenberg leaned vertically on table 2 woods, and a cross between them. Crossing vertically the crossing, he put a turning point, also of wood. Under the turnstile, there is a wooden plate (platin), which goes up and down, as the first turns. Under this wooden plate the frame slides, the turnstile, and the pressure is produced on the whole of the stone base, the rack with the mobile types and the paper.

- This is a very brief description of the press, without the profuse set of technical terms to name each part: Form, galera, canal, volandera, eardrum, frasqueta, cofreand a long etc.

To make this whole mechanism work, several additional things are required: the paper must be moist, so that it absorbs the ink well; and this has to be applied evenly over the letters, and reapplied after printing each sheet.

Gutenberg created an instrument to apply the thick, oily ink of his invention to movable type. This kind of tampon is called a bullet, and it is a kind of half a soccer ball, more or less, with an upper handle, and covered with rawhide, which is passed several times over a flat surface. with a little ink, to soak it up. Then the bullet "smears" the letters several times with several taps, to spread the ink evenly.

First print products

Gutenberg spent many years perfecting the different parts of his invention. It is not known exactly how long, but by 1451-52 he had everything ready to start printing.

Different sources again document his stay in Mainz from October 1448. He signed a loan contract for 150 guilders with his cousin Arnold Gelthus. Gutenberg is believed to have used the loan to build a printing shop. He sought contact with other financiers, such as the businessman Johannes Fust. Around 1449 he gave him an interest-free loan of 800 guilders and received the equipment he had bought with the money as a pledge.

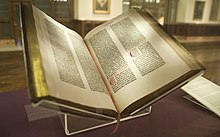

By 1450, Gutenberg's experiments were so advanced that he began assembling and printing small single-sheet books and flyers. Early prints attributed to Gutenberg can be divided into two groups. On the one hand, small prints such as dictionaries, short grammars, indulgences, and calendars; and on the other hand the so-called Gutenberg Bible, also known as the 42-line Bible For a long time it was believed that around 1449 he had printed the so-called Constance Missal, but it is currently believed that this is not the case..

Gutenberg miscalculated how long it would take him to get his invention up and running, so he ran out of money before he was done. In 1452 he again applied to Johann Fust for credit, who this time refused; and faced with the lender's refusal, Gutenberg offered to form a partnership. Fust accepted, contributed another 800 guilders, but delegated supervision of the work to his nephew, Peter Schöffer, who began to work side by side with Gutenberg, while supervising his uncle's investment.

Gutenberg ran out of money again, when he was close to finishing the 180 Bibles he had proposed. But Johann Fust did not want to extend his credit, gave up the debts, kept the printing implements and put his nephew in charge of it; already experienced in the new printing arts as a partner-apprentice of Gutenberg.

Peter Schöffer finished the task his teacher started, and the Bibles were quickly sold to high-ranking clergy, including the Holy See, at a very good price. Commissions for new work soon began to pour in. The speed of the execution was undoubtedly the trigger for its expansion, since before the delivery of a single manuscript book could take years.

The bible took about 2 years to be printed. The first copies were exhibited at the Frankfurt trade fair in 1454. 180 copies were made, each containing 1,200 pages. A few were printed on vellum and the vast majority on paper. Currently there are about 48 of these bibles; about 12 on vellum and the rest on paper. Two are preserved in Spain, one complete in Burgos and another with only the New Testament, in Seville.

48 substantially complete copies are known to survive, including two in the British Library that can be viewed and compared online. The text lacks some modern book characters, such as page numbers, indentations, or paragraph breaks.

Gutenberg Fate

It is generally held that Gutenberg left his printing press bankrupt and that he should have been welcomed by the Elector Archbishop of Mainz, the only one who recognized his work until his death a few years later.

What is known of his later life reveals that he was by no means destitute. After ending his association with Fust, about 1455 he returned to Mainz. Archbishop Elector Adolf II von Nassau accepted Johannes Gutenberg as his court servant in 1465. As a courtier he received clothing, grain and wine every year and was also exempt from services and taxes.

However, when one considers the enormous success of his invention, it is clear that he did not receive all of it. Since the lawyer Konrad Humery received printing instruments from Gutenberg in 1468, a business association between the two is assumed, which allowed Gutenberg to continue working in a printing shop. But it is not known precisely since when.

Until his death, he lived in the vicinity of the house where he was born, in Mainz. The date of Gutenberg's death is not known: but the most reliable source to determine it is the notarized confirmation of the lawyer Konrad Humery, in which he testifies that he received a printing press from Gutenberg's estate, before February 26, 1468. Therefore, the only sure thing is that Gutenberg died before that date. According to a relative's obituary, Gutenberg was buried in the Franciscan Church in Mainz. However, after numerous renovations, the church was demolished in the 18th century century and replaced by a new building. Therefore, it is not possible now to find his grave. No authentic portrait of Gutenberg has come down to us.

Although many people and places in Europe claim to be the origin of the printing press, the current historical consensus is that it was Gutenberg who invented typeface. There is later documentation that attributes the invention to him, although, curiously, his name does not appear in any known print.

The names of the German Mentelin, printer of Strasbourg (1410-1478); that of the Italian Panfilo Castaldi, doctor and later typographer in 1470, the Italian Aldo Manucio and Lorenzo de Coster, from Haarlem, (The Netherlands) (1370-1430). Each has a monument in their respective locations.

An edition dating from 1502 in Mainz, Germany, printed by Peter Schöffer, successor to the printing press that was initially created by Gutenberg, says:

... This book has been printed in Maguncia, where the admirable art of typography was invented in 1450 by the ingenious Johannes Gutenberg and then perfected at the cost and by the work of Johann Fust and Peter Schöffer... among others...

Early Impact of Printing

Between 1400 and 1450, that is, during Gutenberg's life before the printing press, around twenty thousand books had been copied by hand throughout Europe. In the next 50 years in Europe an estimated 12 to 20 million books were printed.

The diffusion of techniques, of knowledge, of exchanges between scholars, and in general in the growth of the cultural heritage that brought about this veritable flood of books, is unimaginable.

If we analyze the attached map, which shows the European cities that had printing presses in the XV century, we see that the Diffusion of Gutenberg's invention was extraordinarily fast. This might not have been possible if Gutenberg had retained exclusive wit for him. At that time there were no intellectual property laws, and the only way a creator could keep an invention (otherwise very rare) for himself was to keep it under strict secrecy. But neither Gutenberg nor Fust were in a position to keep such a secret; and besides, the first needed income to live.

So the bad luck of the inventor, who had to hand over his creation to the lender, allowed there to be no obstacles or secrecy so that the knowledge that allowed the creation of new printing presses could circulate freely everywhere. The gigantic impact of this in the history of humanity has not been properly calibrated.

First printing presses and books in Latin America

In the Peninsula, the first printing press was installed in Segovia in 1472, and its first book is the Sinodal de Aguilafuente. In New Spain, the first printing press was established in Mexico in 1539. In Central America, the first book is Treatise on the cultivation of indigo, printed, precisely, in blue ink. In the Viceroyalty of Peru, the first book is La Doctrina Cristiana (Lima, 1584).

First prints

Gutenberg, in his work as a printer, created his famous incunabula Catholicon, by Juan Balbu de Janna. A few years later, he printed pages on both sides and calendars for the year 1448. In addition, together with his friend Fust, they edited some booklets and bulls of indulgence and, in particular, that monument to primitive printing, the 42-line Bible, in two double-folio volumes, of 324 and 319 pages respectively, with blank spaces to later paint by hand the capitular letters, the allegories and vignettes that would colorfully illustrate each of the pages of the Bible.

According to the statements of various witnesses[citation needed] it turns out that, while apparently manufacturing mirrors, Gutenberg used all the instruments, materials and tools necessary for the secret printing press: lead, presses, crucibles, etc., with the supposed pretext of manufacturing small Latin devotional books with the title Speculum from wood xylographic plates that were manufactured in Holland and Germany with the titles Speculum, Speculum humanae salvationis, Speculum vitae humanae, Speculum salutis, etc. But some declared that under the pretext of printing mirrors, "Gutenberg, for about three years, had earned about 100 guilders on the things of the printers."

Hungary would be the first kingdom to receive the Renaissance in Europe after Italy, under the reign of Matthias Corvinus in the 16th century the first Hungarian printing press would be inaugurated in 1472. Andrés Hess would be called to Hungary from Italy, who, using Gutenberg's system, would organize the Hungarian printing press and have two works published: Cronica Hungarorum (The Chronicle of the Hungarians), and the Magnus Basilius: De legendis poëtis - Xenophon: Apologia Socratis (two classical Greek works in one volume). During the period from 1493 to 1496, the first printing press in Montenegro, known as the Crnojević Press, was considered the first state printing press in the world.

Years later and around 1500 the social situation changed in Germany and a civil war made printers flee in Mainz to avoid falling into war. Printers had a hard time keeping the secret and printing shops spread all over Europe.

The printing press became known in America after the Spanish conquest was over. In 1539 the printer Juan Cromberger set up a subsidiary of his Seville printing press in Mexico City in a local Juan de Zumárraga. This subsidiary will be in charge of Juan Pablos, who began his printing work that same year. Various European printers arrived in New Spain who played a fundamental role in the world of books. The first printer already mentioned was Juan Pablos, he was active from 1548-1560, later Antonio de Espinosa arrived who worked from 1559-1576, the third was Pedro Ocharte from 1563-1592. Pedro Balli is the fourth New Spanish printer, he was active from 1574 to 1600. He arrived in Mexico in the year 1569, as a bookseller. & # 34; He was dispatched to the province of New Spain by bachelor and by royal decree of his majesty, on July 15, 1569 & # 34;.

The chronicler Gil González Dávila wanted to say that the first printed work was Spiritual Ladder to Get to Heaven by San Juan Clímaco in 1532, in its version translated from Latin by a Spanish friar, and although agrees in the title of the book with the historian Dávila Padilla, the date of 1532 is wrong since in that year there were no means to print anything in those lands. The first printed book would be Brief and more compendious Doctrina Christiana, written by Juan de Zumárraga, in Juan Cromberger's printing press managed by Juan Pablos in 1539.

Thus began the greatest impact of the printing press on the culture of mankind. The written word could now reach any corner, people could have access to more books and start worrying about teaching their children to read. Ideas crossed borders and the art of typography was the means of disseminating them.

Books, incunabula, illustrated editions with wood engravings: improved printing techniques and materials took words all over the world for four centuries. Typographic art evolved and came to create masterpieces in the formation and structures of printed books and special editions. Currently, printing techniques in quality and volume have improved impressively, some by means of computers, forgetting the typographic art that many typographers in the world are reluctant to change.

Few inventions have had such an influence on the human being as the creation of the printing press, that ancient art that, if the work of the typographer and the written work of a good author are united in a work, provides a complete work of art, ready to move the reader with literary beauty and typographic aesthetics, the first and last end of the printing press.

At the end of the XIX century, the process was perfected, thanks to the invention of the linotype in 1885, by Ottmar Mergenthaler.

Printing in electronics

The new media appeared at a time of accelerated change and faster communications and were the answer to the increased demand for information and entertainment. New systems and structures never completely erase old ones but rather overlap. Thus, the new information storage and retrieval techniques have required the printing media in this field to regroup and find new placements, often of a more specialized nature.

The audiovisual revolution has been witnessed amid a deluge of printed promotional material. All this has brought with it changes that affect the book; For example, conventional typesetting is now so expensive that it is only justified in very large print runs, but there are a variety of cheaper printing methods, such as photocopying and electrostatic duplication.

The digital printing press

New horizons unfolded with the advent of digital printing. The time and cost savings offered by the new digital techniques are also valid for the publishing industry, which benefits from the speed and extensive possibilities that digital printing offers:

- optimized investment: one of the biggest problems in the publishing industry is that if the volume of a book is not profitable, that book will never be published. Now with digital printing also short strips can be profitable, thus allowing a greater "publication democracy".

- reprint: this means that it will not only be possible to obtain a very low cost in the case of new impressions, but also for reprints on demand. This allows a further productive advantage: to produce less books to save expenses and publish others in the case you sell.

- In addition to the direct advantages, digital printing opens up a new world: thanks to it it is possible to send orders by email, print online, copy texts in a matter of seconds, make quick communications and use universal formats like PDF.

The future of printing

With the appearance of electronic ink and the well-known electronic books or eBooks it has been achieved that it is no longer necessary to print a book to be able to distribute it and therefore read it. Various devices allow the purchase and acquisition of books, publications and magazines from the same device,[1] which significantly reduces the cost of producing intellectual property as well as providing an ecological solution. It is also necessary to highlight the role of the Internet as a great medium for distributing information through web pages and email, often substituting the traditional use of paper in areas such as the written press or postal mail. For these reasons, the use of printing has decreased, and even ecological campaigns invite not to generate waste by printing material that can be seen or read on digital devices, generating greater awareness about what will be printed.

Contenido relacionado

IP on homing pigeons

Maximum transfer unit

Claude shannon