Primates

The primates (from Latin, cousins 'first') are an order of placental mammals to which humans and their closest relatives belong. Members of this group arose between fifty-five and eighty-five million years ago (at the end of the Cretaceous) from small terrestrial mammals. They adapted to arboreal life in tropical rainforests; indeed, many of the characteristics of primates constitute adaptations to life in such an environment: a large brain, visual acuity, color vision, a modified shoulder girdle, and skillfully used hands. Primates range from the approximately thirty grams of mouse lemurs (genus Microcebus) to the 200 kg of the eastern gorilla (Gorilla beringei). New species of primates are continually appearing.: in the first decade of this millennium, more than twenty-five were described, and another eleven since 2010.[citation needed] Some of those discovered are already threatened, as happened with Pongo tapanuliensis, a third species of orangutan.

The order of primates is divided into two suborders: strepsirrhines (which means, in Greek, crooked nose), a group that includes lemurs and lorises and whose species are distinguished by their wet rhinary (wet nose, like that of Dogs and cats); and on the other hand, haplorhines (simple-nosed, in Greek), a suborder that includes tarsiers, monkeys, gibbons, great apes, and humans, all with a dry rhinary.

The infraorder simiiforms, within the haplorhines, only leaves out the tarsiers; the other species are divided between catarrhines (nosed with downturned nostrils), called Old World monkeys due to their geographical distribution, and platyrrhines (flat-nosed, nostrils down). nostrils to the sides), called New World monkeys. This division took place about sixty million years ago. Forty million years ago, there were monkeys from Africa that migrated to South America, probably on rafts made up of fallen trees and other material carried into the sea, where they gave rise to the New World monkeys. Finally, twenty-five million years ago, the remaining Old World apes (catarrhines) split into great apes on the one hand and Old World monkeys on the other. The Old World baboons, macaques, and gibbons are known by their common names, as are gorillas, chimpanzees, and orangutans; also capuchins, howler monkeys and New World squirrel monkeys.

Compared to other mammals, primates have large brains (relative to their body size), and greater visual acuity, at the expense of having lost smell, the dominant sensory system for most mammals. These two features are more pronounced in monkeys than in lorises and lemurs. Some primates (humans, among them) are trichromatic, that is, they have three independent channels for receiving color information. All have tails, except hominoids. Most have an opposable thumb.

Sexual dimorphism is common; there are differences in terms of muscle mass, fat distribution, width of the pelvis, size of canine teeth, distribution and coloration of hair. Among the factors to which dimorphism can be attributed and which are in turn affected by him is the mating system, size, habitat and diet.

Primates develop more slowly than other mammals of comparable size, reach maturity later, and have a longer lifespan. Depending on the species, they live alone, in pairs, in groups of varying composition, and up to hundreds of individuals, with diverse social systems. Some, such as gorillas, humans, and baboons, are primarily terrestrial and not arboreal, but all species have evolved anatomical features that make it easier to climb trees. They have various arboreal locomotion techniques, such as jumping from one tree to another or swinging from the branches (movement called brachiation). Terrestrial locomotion is commonly practiced walking on quadrupeds, but with variants; gorillas and chimpanzees, for example, lean on their knuckles; orangutans, on the outside of the hands. Bipedalism is only observed in great apes, which also adopt this position very sporadically.

Physical contact between human and non-human primates can facilitate the transmission of zoonoses, particularly viral diseases such as herpes, measles, Ebola, rabies and hepatitis. It is precisely the fact that there are common diseases, added to their similarity, psychological and physiological, with the human being, which has led to thousands of non-human primates being used throughout the world for research purposes. Capture for medical experiments or as pets poses a danger to these species, but the most serious threat is deforestation and forest fragmentation. They are also hunted for their meat (bushmeat), and are often shot when they enter crops to obtain food that they cannot find in the confined spaces they are forced to occupy. The result is that around 60% of species are in danger of extinction.

Origin of the name, terminological problems

The name "primates" It was first used by Linnaeus in 1758 in his taxonomic arrangement of animals. The word derives from the Latin primas, primatis, which means “first” in the sense of “main”, that is, it does not refer to a temporal order, but to a hierarchy. This same word was used in the XIII century as a title within the Church, corresponding to the rank of “primate“ (a bishop or high level archbishop).

Linnaeus included humans, great apes, Old World monkeys, and New World monkeys in his order Primates, distinguishing them from other mammals, which he called "Secundates" (seconds), and of all other animals, the "Tertiates" (third parties). He had been unable to find any notable anatomical differences between humans and apes that would allow him to place the former in a separate group from the latter. Still convinced that humans are a special creation of God, and that there is a "scale of nature" (Latin, scala naturae) on which Homo sapiens (name that he invented) occupies a privileged place, he could not deny that humans are animals, and more specifically mammals and primates. And if we abide by the indicated etymology, this name indicates that we occupy a more than worthy place in the group of animals.

The names used in common language to refer to groups of primates present problems when making them correspond with the names used in zoology. According to the RAE Dictionary, a monkey is "an animal of the ape suborder", which is confusing, when mixing a taxonomic name with a common language word; and an ape is an “anthropoid primate”. The word monkey used to cover practically all non-human primates, including hominoids or anthropomorphs, more closely related to homo sapiens, but the influence of the English language has given rise to to hesitation in use. In English, a distinction is made between monkey and ape (terms that the Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines taxonomically in such a way exquisite); The first is, for laymen, a small or medium-sized monkey, which has a tail; the second, larger, does not have it. On the other hand, the use of great ape to refer to hominoids (gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, etc.) has become widespread, but if English speakers no longer get According to whether or not the term includes humans, the more difficult it is to specify what the Spanish speaker refers to when referring to monkeys, simians and great apes.

Features

Although primates are a fairly clearly defined order of mammals, relatively few features are present in all species of this order and in no other mammalian species, i.e., that characterize them distinctly. unambiguous However, according to the biologist Robert Martin, there are nine characteristics of the order of primates.

- The fat toe finger is opposite (with the exception of man), and the hands are fit to grab objects.

- The fingernails and feet are flat in most species (i.e., they have no form of a claw), and the primates have fingerprints.

- In the locomotive they dominate the lower extremities, the mass center is closer to them than the superiors.

- The olfactory perception is not specialized, and is reduced in the primates that are active during the day.

- Visual perception is very developed. The eyes are large and forward (not down), making possible the stereoscopic vision.

- Females have relatively few babies. Pregnancy and breastfeeding last longer than in other comparable-sized mammals.

- The brains are larger than those of other mammals, in relation to body mass, and have some unique anatomical characteristics.

- The teeth are not specialized and there is a maximum of three; they are added a maximum of two incisives, a colmillo and three premolars.

- There are some anatomical particularities that are more useful for systematic studies, but whose functionality is doubtful.

Anatomy and Physiology

Brain

Primates have a large skull, which protects a large brain, a characteristic feature of this group and especially striking in the case of humans: our cranial capacity (which serves as a measure of brain volume) is three times larger than in the largest non-human primate. This volume is on average 1201 cubic centimeters in humans, 469 cm³ in gorillas, 400 cm³ in chimpanzees and 397 cm³ in orangutans. The main evolutionary trend in primates has been the development of the brain, especially the neocortex (a part of the cerebral cortex), which is involved in sensory perception, generation of movements, spatial reasoning, conscious thought and, in humans, the language. While other mammals rely heavily on smell, the arboreal lifestyle of primates has led to a sensory system in which the sense of touch and especially sight dominate, while the areas responsible for a sense of smell have increased. complex social behavior.

Vision

Primate eyes are located in the front of the skull pointing anteriorly. This characteristic gives them binocular vision, which allows them to accurately calculate distances, an essential skill for all their ancestors who moved by brachiation. On the orbits they have a superciliary arch that reinforces the facial bones, weaker, subjected to great tension when the animal chews. Strepsirrhines have a postorbital bar, a bony structure that surrounds the outer part of the orbit; instead, the orbits of haplorhines are completely closed by a postorbital septum.

The evolution of color vision in primates is unique among most eutherian mammals. While the earliest vertebrate ancestors of primates possessed three-color vision (trichromatism), the most recent warm-blooded, nocturnal ancestors lost one of the three types of retinal cones during the Mesozoic period. Fish, reptiles, and birds are trichromatic or tetrachromatic, while all mammals, with the exception of some primates and marsupials, are dichromatic or monochromatic (the latter meaning total color blindness). Nocturnal primates, such as night monkeys and Galagids, are mostly monochromatic. Catarrhins are normally trichromatic due to chromosomal duplication of the red-green opsin gene shortly after their appearance, 30–40 million years ago. Platyrrhines, on the other hand, are trichromatic in a minority of cases. Specifically, females can be heterozygous for two alleles of the opsin gene (red and green) located at the same locus on the X chromosome. Therefore, males are necessarily dichromatic, while females can be dichromatic or trichromatic. Color vision in strepsirrhines is not fully understood; however, research indicates a range in color vision similar to that of platyrrhines.

Like catarrhines, howler monkeys (classified as platyrrhines) frequently exhibit trichromatism, which has been established as a recent chromosome duplication in evolutionary terms. The howlers are one of the platyrrhines with a more specialized diet, based on leaves; fruits do not constitute a significant part of their diet. And the type of leaves they eat—tender, nutritious, and digestible—can only be detected through three-color vision. Field studies to study the dietary preferences of howler monkeys suggest that the tendency to trichromatism is environmentally mediated selection; it is a trait that allows them to eat well despite having a diet with hardly any fruit.

Denture

Primates show an evolutionary trend toward a shorter snout. The New World monkeys are distinguished from the Old World (Asia, Africa) by the structure of the nose: in the former, the nostrils point to the sides; in these, down. On the other hand, there is a difference between Old World monkeys and hominoids (also called « great apes ») in terms of the arrangement of their teeth. There is considerable variety in dental patterns among primates. Although some have lost most of their front teeth, all have at least one lower front tooth.

Strepsirrhines are characterized by a moist muzzle tip, an immobile upper lip, and forward-pointing lower incisors.

In most strepsirrhines, the lower incisors and canines form a dental comb, used for grooming and sometimes foraging. Old World monkeys have eight premolars, those of the Americas have twelve. In Old World primates, the number of dental cusps on the molars indicates whether they are monkeys or great apes; the first have four and the second five; humans may have four or five.

Limbs

Primates generally have five fingers on each limb (said to be pentadactyls), with flat nails (not claws) at the end of each finger. The ends of the hands and feet have tactile pads on the distal phalanges of the fingers. Most have an opposable thumb, a character characteristic of primates, but not exclusive to them (for example, opossums also have it). These thumbs allow the fingers to form a pincer, making it easier to use tools; Furthermore, in combination with fingers that can be fully flexed inward, they are a remnant of the ancient practice of clinging to branches, which in part allowed some species to develop brachiation as an efficient means of transportation. Prosimians have a claw-like nail on the second toe of each foot, called the grooming claw, which is used for body grooming.

The primate clavicle remains an important element of the shoulder girdle, giving the shoulder extensive mobility. Hominoids, compared to guenons (Old World monkeys) have greater shoulder mobility due to the dorsal position of the scapula, a broad ribcage flattened in the anteroposterior plane, and a shorter and less mobile vertebral column. Most Old World monkeys are distinguished from hominoids by having tails. The only family of primates with prehensile tails are the atelid platyrrhines, which includes howler, spider, and woolly monkeys.

Locomotion

The way primates move is related to the way they search for food. In this aspect, primates show a great diversity of types of displacement, which are classified into the following modes: jumping, arboreal quadrupedism, terrestrial quadrupedism, suspensory behavior, and bipedalism.

The jump is present in tree species that move between discontinuous supports. Examples of this type of locomotion are the sifakas (Propithecus verreauxi), in strepsirrhines, which have long, muscular legs. The sifakas move by jumping even if they are on the ground; The squirrel monkey (genus Saimiri), in the haplorhines, has shorter thighs in relation to the lower extremity of the leg, which allows it to generate large jumps. Except for large lemurs such as indris and sifakas, the rest of the jumping species are usually lighter than those primates that move by arboreal quadrupedism, for example squirrel monkeys have weights that range between 0.5 and 1.1 kg.

Arboreal quadrupedalism is better suited to moving through a tangle of continuous branches, and is safer for large primates. Examples include howler monkeys (genus Alouatta) and gray-cheeked mangabeys (Lophocebus albigena) weighing 6.4 kg for females and 9 kg for males.

Terrestrial quadrupedism allows you to move easily on firm ground. Some primates move by making the entire palm of their hands come into contact with the ground, such as baboons, baboons and drills, among others. Other primates move on dry land by supporting themselves on the dorsal surface of the middle phalanges of the second to fifth fingers, not on "the knuckles" as they say. This occurs in the closest relatives of humans, chimpanzees and gorillas.

The suspensory behavior allows the primate to distribute the weight of its body between different small supports avoiding the oscillation of the body. Orangutans (Pongo pygmaeus and Pongo abelii) are examples of this. Some primates have developed brachiation as the main mode of movement between branches. Gibbons (family Hylobatidae) are skilled in this way of moving. In the New World, spider monkeys (genus Ateles), muriquí (Brachyteles) and woolly monkeys (genus Lagothrix) use their prehensile tail like a fifth limb when suspended.

Moving on the hind limbs, or bipedalism, is only present in one extant species of primates: Homo sapiens. However, between 2.5 and 1.8 million years ago several bipedal species shared the planet in Africa, such as Homo habilis, Homo rudolfensis, Homo ergaster and Paranthropus boisei. The discoveries of this coexistence have left behind the idea that there was only one species of bipedal hominid inhabiting the Earth at any time, which was replaced by another in a linear sequence. Bipedal locomotion was already present more than 4 million years ago; Ardipithecus ramidus and the famous Australopithecus were already bipedal. Some scientists consider that this form of displacement in the human lineage can be traced back to 7 million years with Sahelanthropus. The bipedal posture requires a change in the orientation of the femur on the tibia by modifying the angle. Also the function of the gluteus medius muscle is different in bipeds and quadrupeds. In bipedal species, such as man, this muscle acts as an abductor rather than an extensor. Bipedalism appeared in another lineage of primates, this time in regions of present-day Italy that were swampy islands at the time. 8 million years ago Oreopithecus bambolii presented a bipedal movement although its anatomical arrangement of the lower extremities does not resemble that of humans.

Some primates such as the bonobo (Pan paniscus) and the nasic (Nasalis larvatus) move on their hind limbs when crossing flooded areas.

Sexual dimorphism

Sexual dimorphism is common among apes, and more noticeable in Old World primates than in New World species. This dimorphism is seen especially in body mass, length of canines, and color of fur and skin. It varies depending on different factors, including reproductive behavior, size, habitat, and diet.

Cognition and behavior

Primate Societies

Most primates have an active social life. There is practically no species with totally solitary individuals, and there is a great variety of grouping classes depending on the species. There are monogamous monkeys, such as gibbons, which maintain a couple for years, and do not mix with others. Macaques, on the other hand, live in mixed troops of tens of individuals; There may be only one breeding male or several, but in this case the highest-ranking male has privileged access to the females.

Among orangutans, adult males live alone; females and their young often congregate with other mothers. Chimpanzees live in so-called fission-fusion troops: during the day they roam the forest in search of food in small groups, and at the end of the afternoon they all come together to sleep. Among chimpanzees, it is the females who leave the troop to avoid inbreeding, so the males are the ones that are related to each other. In other species, such as macaques, it is the opposite: the groups are matrilineal, the males abandon it when they become adults to look for partners in other groups. The same situation occurs between langurs and gorillas. There are more variants: both male and female howler monkeys leave the natal group when they reach sexual maturity, so in these groups there is no relationship between them.

These social systems are affected by the three main ecological factors; resource distribution, group size and predation. Within the group, cooperation and competition are balanced: individuals groom themselves, share food, protect each other; but aggressive behavior also occurs when there is competition for food, a sexual partner or simply a good place to spend the night. Aggression also serves to establish the hierarchy.

Food

Primates take advantage of a variety of food sources. It has been proposed that many characteristics of modern primates, including humans, derive from their primitive ancestors' practice of obtaining most of their food from the rainforest canopy. Most include fruit in their diets to obtain easily digestible carbohydrates. as a source of energy. However, they require other food, such as leaves or insects, to obtain amino acids, vitamins and minerals. Primates of the Strepsirrhini suborder are capable of synthesizing vitamin C, like other mammals, while those of the Haplorrhini suborder lack this ability and require this vitamin in their diet.

Many primates have anatomical specializations that enable them to take advantage of particular food sources, such as fruits, leaves, resins, or insects. Species that feed primarily on leaves (folivores), such as howler monkeys, colobus monkeys, and lepilemurids, have a long digestive tract, which allows them to absorb nutrients from difficult-to-digest leaves. Marmosets, which incorporate natural gum into their diet, have strong incisors that help them break bark from trees and obtain food. They have more claw-like nails for clinging to trees while feeding. trees. Some species have additional specializations; for example, the grey-cheeked mangabey has thick tooth enamel which gives it the ability to access hard-rind fruits and seeds.

The gelada is the only primate species that feeds primarily on grass. Tarsiers are the only fully carnivorous primate, feeding exclusively on insects, crustaceans, small vertebrates, and snakes (including venomous species). On the other hand, capuchin monkeys can take advantage of a variety of foods including fruits, leaves, flowers, shoots, nectar, seeds, insects, and other invertebrates, as well as vertebrates such as birds, lizards, squirrels, and bats. The chimpanzee has a varied diet that includes predation on other primate species, mainly the western red colobus.

Distribution

Today the distribution of non-human primates is much smaller than it was in earlier times. Today primates can be found living in the wild on all continents except Oceania, Europe and Antarctica. Primates, for the most part, inhabit the jungles, although there are many species that have secondarily adapted to the great savannahs.

Continental drift has played an important role in the current distribution of primates, as have precipitation and vegetation, factors that in turn depend on climate.

Of the two main groups of extant primates, the Old World contains all of the extant strepsirrhines, with the island of Madagascar being especially biodiverse in regards to this group, since it was separated from Africa approximately 88 million years ago, giving rise to the group evolving in isolation. Under these circumstances, lemurs reached a diversity never before known; there was even a species of large herbivorous primate, the giant lemur (Megaladapis edwardsi). Strepsirrhines are also found in Asia and mainland Africa.

Haplorhines are distributed throughout Africa, Asia and America (as far north as Mexico); In Europe there is only one wild population of macaques in Gibraltar (Macaca sylvanus), which was introduced by the English in 1704, so it does not count as the natural distribution of the species. Catarrhine primates are restricted to the Old World, with the exception of humans, while platyrrhine primates are restricted to the Americas, the northernmost species being the black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra), the black howler monkey (Alouatta pigra), the mantled monkey (Alouatta palliata mexicana) and the spider monkey (Ateles geoffroyi vellerosus).

In Asia, the most southeastern distribution is marked by the Wallace line, a biogeographical limit due to a submarine fault (the Wallace fault) that prevented that during the glacial periods, when the sea level dropped and the islands were connected, the fauna will disperse. This biogeographic boundary explains why the Galagus and Orangutans did not reach New Guinea and Australia.

Australia lacks primates since when the Australian plate separated from Antarctica 40 million years ago, the species of this group had not yet reached these southern lands.

Evolution and phylogeny

|

The order Primates is part of the clade Euarchontoglires, which is located within Eutheria in the class Mammalia. Genetic studies in primates, colugos, and tupayas showed that the two colugo species are more closely related to primates than to tupayas, despite the fact that tupayas were once considered primates. These three orders make up the Euarchonta clade. This clade combined with the glires (integrated by Rodentia and Lagomorpha) forms the Euarchontoglires clade. Sometimes both Euarchonta and Euarchontoglires are classified as superorders. Some consider Dermoptera a suborder of Primates and call the suborder Euprimates "true primates".

Evolution

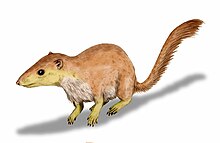

The origin of primates is thought to date back at least 65 million years, despite the fact that the oldest primate known with certainty in the fossil record is Plesiadapis, from 58 to 55 million years ago (late Paleocene to early Eocene). Another mammal, Purgatorius, which existed during the early Paleocene and possibly the late Cretaceous, is not known with certainty. whether it is a primate or a plesiadapiform. Other studies, including analyzes using the molecular clock technique, place the origin of primates at approximately 85 million years ago, in the mid-late Cretaceous.

In modern cladistics, the order Primates is monophyletic. The suborder Strepsirrhini is thought to have diverged from primitive primates around 63 million years ago, although according to molecular analyzes it may have occurred earlier. The seven families of strepsirrhines are made up of the five families of lemurs. and the other two Lorisidae and Galagids. Previous classifications included Lepilemuridae within Lemuridae and Galagidae within Lorisidae. During the Eocene, most of the Northern Hemisphere was dominated by two groups, the Adapiforms and the Omomiids. The former is considered a member of Strepsirrhini, but does not have a tooth comb like modern lemurs; Recent publications have suggested that Darwinius masillae falls within this group. The second was closely related to tarsiers, monkeys, and hominoids. It is not known for sure how these two groups are related to living primates. Omomyidae disappeared around 30 million years ago, while Adapiformes survived until 10 million years ago.

According to genetic studies, Madagascar lemurs diverged from lorisiforms approximately 75 million years ago. These studies, as well as chromosomal and molecular evidence, show that lemurs are more closely related to each other than to other lemurs. other strepsirrhine primates. Because Madagascar separated from Africa 160 million years ago and from India 90 million years ago, it is believed that for lemurs to be more closely related to each other than to other strepsirrhines, a Their ancestral population had to reach Madagascar in a single rafting event between 50 and 80 million years ago. Some other options have been considered, such as multiple colonization from Africa and India, but they are not supported by genetic and molecular evidence.

Until recently, it was not known how to classify the aye-aye as strepsirrhines. Theories have been put forward that its family, Daubentoniidae, was either part of the lemuriformes (meaning that its ancestors diverged from the lemurs after the separation of these and lorises) or it was a sister group to all strepsirrhines. In 2008, the family Daubentoniidae was confirmed to be more closely related to lemurs, and evolved from the same population that colonized the island of Madagascar.

The suborder Haplorrhini is made up of two clades: the infraorder Tarsiiformes, which is the branch that diverged earlier, around 58 million years ago, and the infraorder Simiiformes, which originated 40 million years ago., which in turn contains two clades: the Platyrrhini parvorden, which evolved in South America (New World monkeys), and the Catarrhini parvorden, which thrived in Africa (Old World monkeys). A third clade, which included to the family Eosimiidae, lived in Asia, but became extinct during the Eocene.

As with lemurs, the origin of platyrrhines (New World monkeys) is not entirely clear. Studies based on their DNA sequences have provided variable information regarding the time when the separation between platyrrhines and catarrhines occurred, varying between 33 and 70 million years ago, while studies based on mitochondrial sequences show a narrower range. from 35 to 43 million years ago. It has been postulated that the apes initially originated in Africa and that a population migrated, subsequently resulting in speciation. It is likely that these primates crossed the Atlantic Ocean during the Eocene, aiding each other in the process. of the islands of the mid-Atlantic ridge present by the lower sea level, hopping from island to island to South America. Again, rafting may explain the colonization of this continent by crossing the ocean. Due to continental drift, the newly formed Atlantic Ocean was not as wide as it is today, and research suggests that a small 1-kilogram primate could survive on a raft of vegetation for 13 days. wind speed and currents, it may have been enough time to make the trip between the two continents. In South America, the oldest fossil is Bolivian Branisella, from the Oligocene, about 27 million years old.

Catarrhines spread from Africa to Europe and Asia in the early Miocene. Soon after, lorises and tarsiers spread equally. The first fossil hominin was discovered in North Africa and dates to between 5 and 8 million years ago. Catarrhines disappeared from Europe about 1.8 million years ago.

Already in the Oligocene, paleontologists have a richer fossil record, especially the remains of El Fayum, in Egypt. Here remains of primates related to tarsiers such as Afrotarsius chatrathi have been found. This site also has remains of apes between 30 and 37 million years old. Of these, the most important is Aegyptopithecus zuexis, since it is considered one of the oldest catarrhines. In the same way, the Apidium is another Oligocene fossil that is related to the platyrrhines of South America for having a dental formula similar to that of many of these.

During the Miocene, the group of hominoids originated in Africa, a superfamily to which man and the great apes belong. The Proconsul lived before the separation of the gibbon lineage. After this we find Afropithecus, Kenyapithecus and Morotopithecus, the latter considered the oldest ape with a body plan more similar to living anthropomorphs..

17 million years ago, hominoids left Africa and spread throughout the Old World. In Europe lived Dryopithecus, Ourunapithecus and Ankarapithecus; Sivapithecus in Pakistan, and Lufengpithecus in China. These fossil apes are classified as hominids of the subfamily in which the orangutan is classified (Ponginae).

The diversity of pongins in the Miocene is due to a more benign climate, thanks to which the forests that supported the great apes were more widespread in Eurasia at that time.

About 13 million years ago (mid-Miocene), Pierolapithecus catalaunicus lived in the region of Catalonia, an extinct species of hominoid primate, possible common ancestor of the great apes (gorillas, chimpanzees, bonobos and orangutans). The description of the discovery was first published in the November 19, 2004 issue of Science magazine. The generic name was taken from the location of the discovery in the Catalan municipality of Els Hostalets de Pierola (Barcelona, Spain). The set of fossils was cataloged as IPS 21350.

9.5 million years ago, the ape Oreopithecus bambolii lived in central Italy and Sardinia, then part of an island. Its bipedal locomotion is a case of convergence evolutionary with hominins.

During the Pliocene, savannas spread at the expense of forests. The bipedal hominids Ardhipithecus and Australopithecus appeared in this geological period. At the end of this period, the genera Homo and Paranthropus arose.

Classification of living primates

The following is a list of the families within the order:

- Order Primates

- Suborden Strepsirrhini

- Infraorden Lemuriformes

- Cheirogaleidae

- Daubentoniidae Family

- Family Lemuridae

- Lepilemuridae

- Family Indriidae

- Infraorden Lorisiformes

- Family Lorisidae

- Galagidae family

- Infraorden Lemuriformes

- Suborden Haplorrhini

- Infraorden Tarsiiformes

- Family Tarsiidae

- Infraorden Simiiformes

- Parvorden Platyrrhini

- Family Callitrichidae

- Family Cebidae

- Aotidae family

- Family Pitheciidae

- Family Atelidae

- Parvorden Catarrhini

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Cercopithecidae Family

- Hominoid Superfamily

- Hylobatidae family

- Family Hominidae

- Superfamily Cercopithecoidea

- Parvorden Platyrrhini

- Infraorden Tarsiiformes

- Suborden Strepsirrhini

Phylogeny

There are two main clades of extant primates, the suborder Strepsirrhini (containing the infraorders Lemuriformes, Chiromyiformes, and Lorisiformes) and the suborder Haplorrhini (containing the infraorders Tarsiiformes and Simiiformes). Another great division exists within the Simiiformes, constituted by the Platyrrhini parvórdenes and the Catarrhini. The Hominoidea clade, contained within the Catarrhini, contains the families Hominidae and Hylobatidae. The hilobatids are the gibbons or "lesser apes". Hominids, for their part, are divided into two subfamilies: Ponginae (orangutans) and Homininae. The subfamily Homininae is divided into the clade of gorillas (tribe Gorillini), and that of humans and chimpanzees (genera Homo and Pan, respectively).

Phylogenetic analyzes support the hypothesis that the dichotomy between haplorhines and strepsirrhines occurred in the early Eocene. Function analyzes suggest that early haplorhines were small, nocturnal, insectivorous or frugivorous with tree-climbing locomotion. The shift from nocturnal to diurnal activity pattern was a fundamental adaptive change that occurred at the base of the haplorhine clade.[citation needed]

| Primary |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

There are many reasons to assume that differences between morphological and molecular phylogenetic hypotheses result from limitations of morphological evidence. The consensus obtained in the cladograms for extant hominoids is supported by numerous data.

Relationship of primates with other mammals

The order Primates is closely related to other orders of mammals, with which it forms the superorder Euarcontoglires (Euarchontoglires) within the subclass Eutherians (Eutheria). Recent research on primates, flying lemurs (Dermoptera) and tree shrews (Scandentia) have shown that the two species of flying lemurs are more closely related to primates than to primates (Scandentia), even if all three lineages were considered primates.. These three orders (Primates, Dermoptera, and Scandentia) form the Euarchonta clade. This clade, united with that of Glires (formed by the orders of rodents (Rodentia) and that of rabbits and hares (Lagomorpha)) come to form the clade of euarcontoglires. Some authors give the rank of superorder to the euarcontos, while others assign it to the euarcontoglires. Some even consider flying lemurs to be primates, placing them in a separate suborder, and calling the primates the suborder Euprimates. This last arrangement is not very common in the literature.[citation needed]

Euarchontoglires cladogram

| Euarchontoglires |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Characteristics and evolutionary trends

The group of primates does not have anatomical characteristics that are exclusive to them; all of them can be found in some species of mammals. However, they have certain features that as a whole allow them to be identified. As characteristics of primates can be mentioned:

- Plant feet.

- Pulgar oponible in hands and feet (some species, like man, have lost the ability to oppose the thumb of the foot, others, like Ateles, lack thumb in their hands).

- Hand fingers with bending capacity, divergence and convergence.

- Hand bones such as scaphoids (or navicular), semilunar (or lunate), pyramidal or triquetrum, central and pisiform always present and discreet.

- Numbers present.

- Unspecialized dientition, with bunodoncy, with 2 incisives, 1 canine 3 or 2 premolars and 3 molars in each half of the jaw in prosimios and platyrens, and with 2 incisives, 1 canine, 2 premolars and 3 molars in each half of the jaw in catarrhen.

- Flat pineapples instead of claws (in most species).

- Color vision (in most species).

- shoulder and elbow well developed.

- Well developed brain hemispheries.

- Binocular vision (in different degrees).

- Eye bones surrounded by bone.

During the evolution of the line of primates that has given rise to the human being, certain trends are observed in their anatomy. These trends are:

- Preservation of five fingers on the limbs.

- Increase the free motility of the fingers, especially the thumb.

- Replacement of the claws by flat nails.

- Progressive decrease in the length of the snout.

- Lower dependency on the sense of smell and greater dependence on sight.

- Preservation of the simple cusp pattern in the molars.

- Progressive development of the brain, especially the cerebral cortex.

- Progressive development of the verticality of the trunk.

- Prolongation of postnatal life periods.

- Development of gestational processes related to fetus nutrition.

Conservation

Like many other groups of organisms, many primate species are threatened with extinction. Man has driven several species to extinction since they began to disperse around the globe.

The main factors that threaten primates are:

- Habitat destruction. Undoubtedly the destruction of the habitat is the main cause that is contributing to the disappearance of the wild populations. The continued growth of the human population leads to the destruction of more forests every day by the expansion of cities and in search of arable land and for the extraction of wood. Nearly 90 per cent of non-human primates live in the wet forests of Africa, Asia, Central and South America and these forests are being cut at a rate of more than 10 hectares per year.

- Cacery of primates for meat consumption. In the jungles of Brazil, primates such as howling monkeys (Alouatta), the knots (Lagothrix) and the Capuchins (Cebus) are regularly hunted by their flesh. In Africa, monkeys and apes are shot and sold on the market as "exotic meat." Hunters usually prefer larger species, for example in Africa hunters prefer to hunt species Colobus that Cercopithecus, but as the number of individuals of large species decreases they pass to smaller ones. Other organizations mention that this practice can put human health at risk as the practice of hunting and consumption can favor the passage to humans of viruses such as Ebola and Immunodeficiency Virus in apes (VIS, evolutionary ancestor of HIV).

- Traffic of primates as pets or for obtaining products. The primates are also hunted for other purposes, the flesh of the langur (Trachypithecus johnii) and the thick lion tail (Macaca silenus) is sold for alleged aphrodisiac and medicinal properties. Similarly the blood of Phayre's langur (Trachypithecus phayrei) in Thailand is marketed because there is the belief that imparts vigor to those who drink it. In South America the nun monkeys (Lagothrix) and spider monkeys (Ateles) are trapped to be used as bait to capture ocelots and jaguars. Similar luck run other species of primates in Sri Lanka where they are captured to be used as bait in crocodile hunting.

In many countries, primates are sold as pets, but for this they must be captured as babies, killing their mothers in the process. Elsewhere primates are killed as pests for agriculture; This is the case of the species of capuchins (Cebus), savannah baboons (Papio), and macaques (Macaca) in America, Africa and Asia respectively.

Primates have also been captured to enable medical research. The highest number of captures was reached in the 1950s and continued into the 1960s, reaching hundreds of thousands. Large numbers of rhesus macaques (Macaca mulata) were exported from India, in efforts that led to the development of a polio vaccine. Squirrel monkeys (Saimiri) were exported from South America for experimentation. The appearance and expansion of the HIV virus led to the capture of hundreds of common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes) to find a cure for AIDS.

Primate species in danger of extinction are listed by the International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources (IUCN). This entity makes the "red list" of species threatened with extinction. It is noteworthy that since the publication of the first "red list" the number of threatened primate species increased from 96 to 166 among the 600 existing on the planet. The number of critically endangered primate species rose from 13 to 19 since 1996. The report also documents the recent extinction of one primate species, Miss Waldron's red colobus, a primate native to the jungles of Ghana and the Ivory Coast.. The destruction of the forests by logging activities and the construction of roads created fragments of forest or isolated pockets devastated by hunters dedicated to the lucrative business of wild meat.

Superstitious beliefs have also had to do with the elimination of the aye-aye (Daubentonia madagascariensis). This primate is killed by the locals in Madagascar because they consider it an "bad omen" due to its nocturnal habits and particular appearance.

Critically Endangered Primates

The IUCN reserves in its Red List the category "Critically endangered" (Critically endangered, in English) to those species that have the following characteristics: Its extension is less than 100 km² and its population is estimated at less than 250 mature individuals, or if quantitative analyzes indicate the probability of extinction in nature of 50% within 10 years or in three generations.

Critically endangered strepsirrhine primates

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Hapalemur aureus | Golden lemur |

| Hapalemur simus | Big bamboo lemur |

| Propithecus tattersalli | Tattersal or crowned sifac |

Critically endangered platyrrhine primates

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Ateles hybridus | Spider monkey of Magdalena or marimonda of Magdalena |

| Brachyteles hypoxanthus | Muriquí del Norte de Brasil |

| Callicebus barbarabrownae | North Bay Titian Monkey |

| Callicebus coimbrai | Coimbra Tit Monkey |

| Cebus xanthosternos | Copeted cappuccino |

| Leontopithecus caissara | Titi black-faced lion |

| Leontopithecus chrysopygus | Black lion |

| Oreonax flavicauda | Yellow-tailed hut |

| Saguinus bicolor | Tamarino bicolor |

Critically endangered catarrhine primates

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Hylobates moloch | Silver Gibón |

| Macaca pagensis | Macaco pagoi |

| Nomascus nasutus | Gibón de Hainan |

| Pongo abelii | Orangutan de Sumatra |

| Procolobus rufomitratus | Red Collobo of the Tana River |

| Rhinopithecus avunculus | Langur ñato Tonkin |

| Trachypithecus delacouri | Black Dorso Langur |

| Trachypithecus poliocephalus | Golden head Langur |

Endangered Primates

A species is considered in danger of extinction if the extension in which it inhabits is less than 5000 km², if the number of its population is less than 2500 individuals or if the quantitative analysis shows the probability of extinction is 20% within of the next 20 years or in five generations. These are the primates in danger of extinction, according to the IUNC:

Strepsirrhine primates threatened with extinction

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Allocebus trichotis | Lémur orejipeludo |

| Daubentonia madagascariensis | Aye-aye |

| Galago rondoensis | Gálago enano |

| Indri in | Indri |

| Loris tardigradus | Loris fino |

| Microcebus myoxinus | Pygmy mouse lemur |

| Microcebus ravelobensis | Rhove mouse lemur |

| Varecia variega | Gorguera lemur |

Platyrrhine primates threatened with extinction

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Alouatta pigra | Araguato de Guatemala o Mono aullador negro |

| Brachyteles arachnoides | Muriqui |

| Callithrix aurita | Titi of white ears |

| Callithrix flaviceps | Beige head titty |

| Satan Chiropots | Black Sakí |

| Leontopithecus chrysomelas | Titi golden-headed lion |

| Leontopithecus rosalia | Titi golden lion |

| Saguinus oedipus | cotton-headed Tamarin |

| Saimiri oerstedii | Central American squirrel monkey |

Catarrhine primates threatened with extinction

| Scientific name | Common name |

|---|---|

| Cercopithecus diana | Window |

| Cercopithecus erythrogaster | Red belly neck |

| Cercopithecus preussi | Preuss Cercoiteco |

| Cercopithecus sclateri | Sclater Pig |

| Gorilla beringei | Mountain gorilla |

| Gorilla gorilla | Western Gorila |

| Hoolock hoolock | Gibón Hulok |

| Macaca maura | Macaco moro |

| Macaca nigra | Macaco Crested of the Celebrities |

| Macaca silenus | Macaco Liontail |

| Mandrillus leucophaeus | Drill |

| Nasalis larvatus | Narigid monkey |

| Nomascus concolor | Black Gibón |

| Pan paniscus | Bonobo o chimpancé pigmeo |

| Pan troglodytes | Common chimpanzee |

| Pongo pygmaeus | Orangutan de Borneo |

| Presbytis comata | Langur grey |

| Procolobus badius | Colobo herrumbrous oriental |

| Procolobus kirkii | Zanzibar red collobo |

| Procolobus pennanti | Pennant Colobo |

| Pygathrix nemaeus | Langur Duoc or monkey pigatrix |

| Pygathrix nigripes | Black-footed Langur |

| Rhinopithecus bieti | Langur ñato negro |

| Rhinopithecus brelichi | Langur ñato gris |

| Concolored Sims | Langur pig tail |

| Trachypithecus auratus | Langur Javanese |

| Trachypithecus geei | Golden Langur |

| Trachypithecus vetulus | Red-faced Langur |

Relationship with man

Nonhuman Primates in Culture

Different human cultures have been interested in the intelligence, grace and similar mannerisms of non-human primates that have made them part of their folklore, art and religion, so references to them are found in many cultures.

The Hindus have within their pantheon of gods Hanuman, the monkey god. This god is considered very powerful, and he is assigned a very important role in the fight of the god Rama against the demon Ravana.

In Muslim cultures, primates are not hunted for food because their meat is considered unclean, while in India it is believed that as they are related to the god Hanuman they should not be killed. In Madagascar there are taboos that prevent the killing of lemurs, but these traditions are being lost.

In Chinese mythology, Sun Wukong, the Monkey-King travels with Chu-Bajie and famous monk Hiuna-tsang to India to obtain the original sources of Buddhism, a journey narrated in the story Journey to the West.

The Chinese also made a zodiac in which they have the monkey as one of their signs. The Chinese assigned ad-hoc the characteristics they observed in monkeys to people born in the year of the monkey. Such as being playful, intelligent, thoughtful, vain, etc. The last year of the monkey was 2016, and the next will be 2028.

Dyehuty (in Egyptian), Thot or Tot (in Greek), is the god of wisdom, writing, music, and symbol of the Moon, in Egyptian mythology.

The Egyptians represented the god Djehuty (or Thoth in Greek) as a baboon-like man with the head of an ibis. This god is credited with great wisdom and power over the other gods.

A legend of African creation of the peoples of Mozambique tells the story of Mulukú, a god who made the first couple from which we all descended sprout from the earth. Mulukú was an agricultural expert, so he taught the first couple the trades of planting. This first couple was disobedient, spoiling the cultivated fields. Mulukú punished them by turning them into monkeys. The myth tells that Mulukú, full of anger, tore off the tail of the monkeys to put it on the human species. At the same time he commanded the monkeys to be humans and the humans to be monkeys; he placed his trust in them, while he withdrew it from humans. And he said to the monkeys: "Be humane." And to humans: "Be monkeys".

Maya cosmology assumes a series of worlds that succeed one another. Mayan mythology narrates that after the second world came to an end after a great hurricane. The god Kukulkan transformed the survivors of this catastrophe into monkeys.

In the Chimú culture, monkeys also come from previously created human beings. In this case, the god Pachacámac is in charge of the transformation after winning a battle against the god Kon, creator of the first human lineage.

In the Middle Ages, Europeans' knowledge of nonhuman primates came from sailors, traders, and travelers to faraway lands, who brought a grotesque mix of zoology and fables. Stories about the "hairy men of the jungle" and "wild men" that the interpreters called "gorillas" (N'Guyala) or "pongo" (M'Pungu) depending on the region. As early as the 17th century Dutch settlers in Asia described orangutans as "wild men" or "Indic satyrs", in fact, the Dutch anatomist Nicolaas Tulp classified all "hairy men" of the Asian jungles as hunter-gatherer peoples. The name "orangutan" comes from Indonesian / Malay: "orang" means person, and "hutan", forest; thus, it is the man of the forest. In a curious reversal of roles, there is a monkey called násico that in Indonesia they call " Dutch man" (orang belanda).

Contenido relacionado

Theodor Schwann

Biocoenosis

Stenohaline