Prehistoric art

Prehistoric art is an artistic phenomenon with a global geographic scope and a sufficient temporal span to affect the most diverse eras. The concept is much more extensive than the Quaternary rock phenomenon, mainly confined to Western Europe, and also includes the manifestations of the so-called Paleolithic art.

Although chronologically, Europe should come first, and despite the fact that many of the prehistoric artistic expressions are relatively recent in some parts of the globe, where primitive peoples have survived, the exhibition will be arranged in alphabetical order. Although this leads to an additional problem: is it lawful to compare manifestations so far away in space and time? In this sense, the confrontation of cultural equivalences, ignoring empirical particularisms, allows generalizations to be obtained.

Based on this, it can be seen that, in the plastic and visual arts of primitive peoples, realism is something exceptional, compared to symbolism, abstraction, stylization and schematism, which seem to be a global constant.

Another possible generalization is that almost all Holocene rock art occurs outdoors, at most in rock shelters, gorges, and shallow coves.

Thirdly, megalithism and the construction of burial mounds, in relation to the cult of the dead, or the need to develop defensive architecture, often with cyclopean constructions (whose motivation far exceeds the needs military), are also constants of world prehistoric art.

Finally, there is the fact that, despite the undeniable religious significance of prehistoric art, it is not only associated with the funerary or mythological world, but the themes cover all facets of human social life (hunting, war, jobs, human ceremonies, hierarchies, sex, family, even fun...) and, above all, as human societies evolve, the glorification of power and the powerful.

Introduction

Prehistorians consider all realistic or schematic graphic references made within the framework of pre-technical and non-literary societies to be works of art. Prehistoric art has constant techniques, themes, location, and variants produced by traditions shared between neighboring groups or in limited periods of time.

Archaeology analyzes the shape of the material remains of the past, Cultural Anthropology and Ethnography help to understand the changes in tools and mentality. Those who study prehistoric art are concerned with identifying themes and styles, and defining the cultural setting; they almost never pass the pre-iconographic analysis and barely manage to recognize the scenes or the meaning of the representation.

Very little remains of prehistoric art: only engravings, paintings and sculptures that have withstood the test of time and that Archeology has managed to recover. The intentions of the authors and recipients of the prehistoric art are unknown, since there is no contemporary information, neither oral nor written.

To find out when these manifestations were made, the order of the superimpositions and patinas of the rock figures is usually studied, as well as the characters of the works that were deposited on the floor of an inhabited space or a funerary enclosure. It is not difficult to perceive the succession of themes and styles of the objects recovered in an excavation. The chronological scheme is applied by induction to the larger figures drawn on the walls of the cave or on rocks in the open air. This is how a picture is established that defines the styles of prehistoric art and the succession of forms and techniques.

Recognition of prehistoric art

The last quarter of the XX century saw an increase in rock art finds, and international programs of documentation. Methods began to be available for a direct dating of the pictorial material and the support of a work to identify the representation techniques, such as the composition of pigments and the development of graphics, the authors and to know how the themes are combined. When proceeding with the authentication of the rock ensembles discovered in the 1990s, it has been possible to resort to a complex analysis to find out aspects that are not perceptible to the naked eye, such as a painted area in the Zubialde cave.

A protection policy has been generalized that tries to counteract the overload of tourist use of ensembles, such as the caves in France and the caves in Spain, environmental contamination, such as acid rain, or the proliferation of exhibitions. Knowledge of the aggressive factors and their possibilities of control and the limitation of visits and manipulations begin to reduce these types of risks.

Origins

Many primitive peoples drew figures and signs on supports that do not resist the passage of time, such as wood, bark, fibers or leather, and were made with colored earths, paints or tattoos on the body. As they have not been preserved, they have not been able to be studied by Archaeology.

In the Middle Paleolithic and in the period of transition to the Upper Paleolithic, between 125,000 and 35,000 BC. P., the Neanderthal man collected materials of striking shapes and colors, such as rock crystals, ocher or red iron oxides, shells and fossils, which they took to caves and placed next to the dead. His artistic intention is discussed in some strokes on bones and stones, such as those of Pech de l'Azé or those of Riparo Tagliente. In spite of everything, it is possible to recognize Homo neanderthalensis the first artistic manifestations, which come from about 65,000 years ago, as confirmed by the remains found in the caves of Maltravieso (Cáceres), Ardales (Málaga) and La Pasiega (Cantabria).

The Cro-Magnon man owes progress in tooling with very careful work of flint, antler, bone and ivory and the funerary device. He is also the author of images related to the world around him, such as small animal figures carved on ivory in the early Aurignacian of southern Germany, between 33,000 and 26,000 BC. C. Later, rock art developed on the Cantabrian coast and in the south of France, with traces made with fingers on the mud of the Pech Merle cave, as well as signs and animal and human silhouettes made both in caves and on utensils., like a piece by Georges Laplace obtained from the Gatzarria cave.

Prehistoric art in other regions

By studying the changes in equipment and the arrangement of dwelling or burial places in the different strata of an archaeological site, the Prehistory of Europe recognizes the order in which different cultures have been produced.

In regions such as Africa, the Americas and Oceania, primitive or aboriginal ways of life have endured until recently, offering an "ahistorical art" that has had to be classified by the appearance of its formal evolution or resorting to the model of styles recognized in European prehistory.

African art

There are rural peoples in Africa who to this day preserve ancient stylistic traditions of rock art despite the influence of the pre-established patterns of Art and Beauty of contemporary Western cultures. In this sense, they have managed to safeguard these cultural heritages despite the pressure of foreign colonizers who brought with them discriminating artistic ideologies among those we have, for example the Islamic iconoclastic trend. However, in this section we will focus on prehistoric art itself, that is, until the arrival of the Europeans, in the 15th century and XVI, when the Yoruba, Benin, Sao and other great cultures were at their height, nipped in the bud due to the beginning of colonial exploitation.

African Art in the Stone Age

The first African artistic manifestations date back to Paleolithic times, but they are very rare: on the one hand, we have the dubious Venus of Tan-Tan (Morocco), and on the other, the strongest testimonies from southern Africa, such as the Blombos cavern (South African Republic), about 70,000 years old, where there are balls of mineral ocher (hematite) decorated with parallel incisions, reticulated and with geometric motifs (some come from ritual burials). It has been known for a long time that ocher could be used to paint body decorations, however, it is the first time that this species of pigment pencils preserves some kind of intentional decoration. Also datable to the Paleolithic is the platelet painted with an unidentified zoomorph dated to 25,000 years old from the Apollo 11 cave (Namibia), where, in addition, there is much later wall art attributed to the Bushmen.

The rest of the known prehistoric African art is much later, probably post-Neolithic. During the Stone Age we distinguish the following regions:

North Africa

The enormous set of cave paintings in the mountains of the center-south of the Sahara stands out especially: Ahaggar, Tassili, Tibesti, Fezzan..., which constitute the largest cave nucleus in the world. This region must have been, in remote times, much more humid and rich in fauna, since the representations are surprisingly rich in wild fauna (elephants, giraffes, buffaloes, hippos) and domestic (rams, oxen, camels...). The scenes are full of life and optimism, there are families, young people diving, etc. There are probably several stages, a first phase with peoples who knew livestock and subsistence agriculture, but practiced buffalo hunting (IV millennium BC), a second phase of long-horned ox herders in which their caretakers carry large arches (3rd millennium BC) and a third in which riding animals (horses and camels) that appear at full gallop are already known, as well as the chariot (2nd millennium BC). Part of this chronology is contemporary with Ancient Egypt and, in fact, in some of the representations contacts of the Sahrian peoples with the Egyptians are demonstrated.

- Rupestres Stations in the Sahara, with some influence of Egyptian art and other later arts

East Africa

In East Africa, Louis Leakey himself has studied a series of rock paintings in the Lake Tanganyika and Lake Victoria area, depicting elephants, rhinos and buffaloes. They are poorly dated and little-known works. Also notable, in Central Africa, are the Tulu Refuge and the Kumbala Refuge, with stylized characters, some in blue and others in white, very different from those of southern Sahara.

Southern Africa

This area supported a series of tribes of the group called San whose level was in the middle of the Stone Age when the Europeans arrived. The San lived with the various Bantu groups who, although contemporaries, already knew metals and, therefore, are studied in the following section. The San or Bushmen developed a rich rock art throughout this area (highlighting Namibia, Drakensberg and Transvaal), in numerous caves and covachas, whose maximum antiquity is disputed, but it could be placed in the fifth millennium and which last until very recent historical times. His art is stylized and fresh, although not as lively as the Saharan, and his motifs are ritual scenes and animals from the environment, but his polychromy is richer and more brilliant (especially in later works):

- San Rupestres Stations in Southern Africa

Ancient African Art

Curiously, despite being the cradle of humanity and African ethnic wealth, discoveries are much scarcer than in Europe or America due to the difficulty of finding and accessing the deposits, socio-political problems and that large areas of the continent have only begun to be explored very recently. The news of great ancient states (of which we except Ancient Egypt) are those that have guided a series of discoveries that, on the other hand, are still isolated and fragmentary:

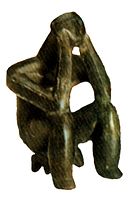

- Nok Culture: It is a culture that developed in northern Nigeria between the 5th century BC and the 3rd century AD. They were acquaintances of iron metallurgy and, artistically, they stand out for being the initiators of the African statuery, in this case, of terracotta. Nok sculptures are of a very mature technical and stylistic design, which makes it suspicious that it must have been precedents (at the moment unknown). These are stylised works, exquisite elaboration and iconography based on the human figure. Its function is ignored, since so far the best known specimens come from stable villages (e.g., Samun Dukiya and Taruga, along the Benué River), but they were certainly religious achievements. Nok terracottas are considered a history of Yoruba and Benin sculptures.

- Civilization of the Sao: it was given on the shores of Lake Chad, specifically in the valleys of Logon and Chari; immediately after the disappearance of the nok, although its apogee takes place between the ninth and sixteenth centuries. Almost all sao art is funerary, specifically it is vases and cups decorated with anthropomorphic representations and zoomorphas; but there are also bracelets, pendants and chests cast in bronze by the technique of molding to the lost wax. It is worth noting the simplicity of its architecture, which has come to this day: it is the huts and barns of circular plant and elevation in ojival dome, made in upholstery and adobe and with the external surface curiously decorated with slips of various forms, the most common, are in in inverted grapes. (musgus) or in the form of rings (masses)that not only improve the aesthetics of the construction, but serve to climb through these outgoings and repair the deteriorations easily.

- Munhumutapa Civilization: This is a kingdom that flourished in the present state of Zimbabwe between the 11th and 15th centuries, of a Zulu ethnic group called shona, whose capital was called Great Zimbabwe, probably the largest city in ruins of all black Africa and that in its best times it must have had 18 000 inhabitants; but linked to it there are hundreds of towns on the banks of the Zambeze Rivers, all over the country.

His art is especially characterized by a monumental granite architecture, generally defensive, but also known objects of gold, furniture and ceramics. Among the remains were fragments of Chinese porcelain from the Song dynasty that suggests the high degree of commercial munhumutapa, perhaps based on the control of aurferous deposits.

- Yoruba Country: The Yoruba are a town in southern Nigeria that around the ninth and twelfth centuries constituted an important kingdom, whose religious centre was the sanctuary of Ifé (or Ilé-Ifé), where the high priest or oni governed a wide federation of state cities. Ifé accumulated numerous riches and promoted the development of a technically highly advanced courteous sculpture of prodigious quality, along with majestic, and balanced. They predominate the bronze or terracotta heads, of a surprisingly realistic style, which many have associated with the classic European ideals (the qua has raised no few disputes), despite their undeniable African traits. There are also carved heads in Esié, another sanctuary, but their style is much more coarse. This dichotomy is explained by the existence of an official art, at the service of the kingdom, capable of reaching high levels of perfection, against non-Coursian artists, more free but linked to the ancestral models of animist religion of the tribes.

- Kingdom of Benin: In the 13th century, an ancient kingdom of Adja ethnicity emerged in the current state of Benin, whose highest peak took place in the 16th century and was often known by Europeans as Dahomey. The main concern of the Adja was to organize to avoid the attacks of slave traders, founded important cities such as Abomey, Agdanlin and Ajatche, became centralized, formed a professional army and appointed a monarch, the oba. They themselves ended up becoming slave traders, with what the oba He obtained important benefits; until they became vassals of the Yoruba, first and then they were conquered by the English (1897).

In their long-standing existence, the Benns have left several thousand monumental bronze sculptures (heads of kings and queens, roosters, leopards), as well as ornamental reliefs that undoubtedly shook their monuments. In addition, elements of furniture art are known: bracelets, swords, masks, carved ivory, etc. The first sculptures have clear yoruba influences, from whom they may have learned the mold to the lost wax. The maximum eclosion of his art occurs between the fifteenth and the seventeenth centuries, when a powerful European influence is appreciated, especially Portuguese. Decay begins in the 18th century, the Benin lose resources and are forced to build works of brass-lined wood, and a more stereotypical style with little originality indicating a clear cultural deterioration.

African primitive art continues to develop today, its most active centers being West Africa (Dogones, Ashanti, Yorubas, Ibos...) and Central Africa (Bamikeles, Fangs, Bakubas, Balubas, Bambaras...).

American Art

Preclassical American Art

America has one of the shortest, most intense and richest prehistoric stages in the world. Pre-classic and pre-Columbian classical civilizations have been excluded from this article, focusing on the period from the appearance of the first known artistic works, to the manifestations of the early or formative horizons, that is, the beginning of the preclassic period (that is, except for the case of the Amerindians of Oasisamerica and the rest of North America, we will deal with periods before our era).

The oldest testimonies of American art

One of the oldest testimonies that has been located in America is in Pedra Furada, in Brazil, where, together with much more recent artistic manifestations, a home dating from 14C to 17,000 ±400 years old was located next to which there were some parallel red strokes that were unquestionably a very sketchy but intentional artistic creation.

In fact, everything seems to indicate that the first American works of art have that extremely simple, non-figurative schematic character. This is the case in the Clovis cave (New Mexico) where sandstone plates with incisions of different geometric motifs dating back to the end of the Pleistocene were exhumed. A special case is the one offered by the Patagonian deposits of the Pinturas river valley (in Argentina). Two important cave complexes of extensive chronological duration have been located there, with the oldest dates obtained from the eighth millennium BC. C. (14C), however, there are much older archaeological levels (up to 14,000 years old) in which natural pigments have been found (iron oxides, gypsum crystals, etc.) that had been mixed with other substances, that is, they had been manipulated by humans. in order to achieve adherence to the rock. These mixtures, when analyzed by the X-ray diffraction method, turned out to be identical to the oldest paintings located in the Cueva de las Manos, which suggests that some of them could be extremely old, that is, from the end of the century. from the Pleistocene (more than 13,000 years old according to 14C). However, there is no direct evidence linking the pigments found in the excavations with the paintings, nor is it known what their motifs or appearance would be.

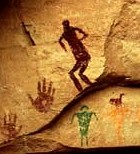

However, the Patagonian stations of the Alto Río Pinturas Archaeological Complex (especially the aforementioned Cueva de las Manos and the Cerro de los Indios), deserve some attention. Its main researchers, Grandin and Aschero, believe it is possible to establish three stages in this great cave complex: the first and oldest, dated between 7700 B.C. C. and 5500 B.C. C., is made up of hands and scenes of great dynamism with stylized anthropomorphs hunting guanacos. The second, dated between 5500 and 1400 B.C. C., is a less dynamic set, but more colourful, the main theme is still the hands, but there are also numerous stylized zoomorphs of very varied colors (white, dark red, violet, ochre...). The third phase goes from 1400 B.C. C. to 1000 AD. C., is the poorest, stylization has been replaced by schematization and various geometric motifs have been added to the hands[2]. As has been pointed out before, there would remain a phase, prior to all the others, deduced only by inferences, about which almost everything is unknown except its great antiquity and can only be considered as a working hypothesis, until its existence is verified.

Parallel to the development of Patagonian paintings, rock art spread throughout South America, important examples being the paintings of Toquepala (in which dates of 7630 BC have been obtained), Lauricocha and Chaclarragla (Peru) with large representations, like those of the schematic phase by Pedra Furada and Ferraz Egreja (Brazil); also Mont du Mahuri and Kourou (Guyana), among others, all of them dated in the Holocene.

Regarding North America, there is an important cave complex in Baja California, the most important cave is that of San Borjita, with schematic human and animal representations. Other caves in the same area are the Cueva pintada del cañón de Santa Teresa, the Cueva de los Venados and the Cueva de la Cañada de la Soledad. Regarding caves with hands as the main theme, these are not limited to Patagonia, in fact they are all over America, for example, the cave in the municipality of Villa Mojocoya (Bolivia), Corinto (El Salvador) or Finger Print Cave (Texas).

North America until the formative period

At the same time that the second phase of hands was being painted in Río Pinturas, they were being developed in more advanced areas of America (the Andes, Mesoamerica, Oasisamerica, the Ohio-Mississippi river valley, in British Columbia and in Eskimo territory...), great agro-pottery civilizations that will precede the pre-Columbian classical civilizations. The artistic variety is extraordinary, and can only be unified based on its adaptation to the environment, the great inventiveness and the variety of forms of expression. From the portable wooden houses of the northwest of North America, to the mud houses in the Chaco Canyon, the Panamanian molas, the Hopi mushrooms or the Amazonian feather masks (not counting the rock forms), there is such a variety that in this article we can only give an overview.

In North America, a series of nomadic peoples with very primitive tribal traditions coexisted and who, although they knew certain advances, lived in conditions similar to those of the Stone Age, together with others who developed very advanced cultures in which, although not States came to exist in the style of those of the classical period (Mayas, Aztecs...), they had a strongly structured organization. The latter basically follow three traditions:

Hohokam and Mogollon

Both are Indians of the Cochise tradition: the Mogollon and the Hohokam. The Cochise tradition is named after an eponymous lake (now known as Willcox Beach); It occurred in Arizona and New Mexico and is the ancestor of the Mogollon culture. This people inhabited the Sierra, so called, of New Mexico, around 200 B.C. C. Its components were sedentary farmers and are considered the first potters of the American West. Being a long-lived culture, they perfected their ceramic technique, until reaching an exquisite finesse, with a decoration between naturalistic and stylized, full of movement (almost all the known pieces appeared in tombs and, apparently, were unused in the burial).. In addition to ceramics, shell necklaces, bracelets, and bone rattles appeared in some tombs.

Perhaps also inheritors of the Cochise culture were the Hohokam of Arizona, noted for their elaborate irrigation systems (which we will not discuss here, as they are not the subject of the article). The Hohokam, in addition to extraordinary pottery richly decorated in red and brown, made crude anthropomorphic figurines and polished slate mirrors adorned with pyrite mosaics. Another surprising form of Hohokam artistic expression was acid etching of saguaro shells, creating patterns by protecting the shell with a film of natural resins. Both the Mogollones and the Hohokam seem to have had strong ties to Mesoamerica in its most advanced phases, a thousand years after the beginning of our era, since courts for the famous ball game have been found.

Anasazi

The primitive Pueblo Indians, known generically as Anasazi and whose evolution is often referred to as the Pecos classification. In this classification, nine phases are established, among which the three oldest correspond to the so-called basket makers (basketmakers) peoples, which, in general, span from the 13th century B.C. C. until the 8th century AD. C.. As is presumable, these towns owe their name to the mastery with which they made baskets, with geometric decoration, and other objects made of wicker, yucca fibers and even human hair. The basket-making villages mark the transition from a hunter-gatherer economy to another clearly agro-pottery, with crude pottery and no livestock (if we except dogs). Large necropolises are preserved in which the corpses were accompanied, knotted, by rich grave goods, which are an invaluable source for the knowledge of this town.

The following four phases are those properly dedicated to the Pueblo Indians or, more appropriately, Anasazi, having a last phase already considered historical. The most striking characteristic of the Anasazi is their architecture and, specifically, their towns, which arose in their heyday (between the year 800 and the year 1000). We highlight two of them because they show two different morphologies:

- Green Table (Colorado): is an impressive set of villages (destacando Cliff Palace), built on the wall of cliffs (mesas or cliff-dwellings, in local terminology), more than 30 meters high, with arch shape. The more than two hundred semi-troglodyte rooms are accessible only from above, through tortuous paths and were able to accommodate hundreds of inhabitants. The buildings were closed with walls of adobe or masonry and in front of its terrace were the circular rooms that used as sanctuaries, kivas or ciurcular wells that were at the time covered. According to later traditions, the Taos of New Mexico (one of the villages that descend from the Anasazi) say that the creator god Itaiku taught men the model with which to build their villages.

- Pueblo Bonito (Chaco Canyon in New Mexico) is a different type of village, not on the cliff wall, but on its base. Built in adobe, shaped like a walled half moon, it has several superimposed plants, staggered, without streets or alleys and with a double central courtyard. Semicircular terraces give you a characteristic form of amphitheater. To the houses, semi-hunted, were accessed from above, from a common terrace where most of the daily and social activities were carried out. The dwellings also include the kivas (more than 50), similar to those of Meda Verde: circular, with access from the top (although they have lost the plug): they were places of social or ceremonial meeting.

There are, of course, many more important sites, such as the necropolis of the town of Pecos (Santa Fe, USA), with more than two thousand burials; Utah petroglyphs and rock paintings; the exquisitely decorated ceramics, bone flutes, stone pipes, necklaces, earrings and bracelets made of bone, coral, jet or turquoise.

The Mound Builders

Late Prehistoric mound building is a phenomenon that occurs throughout the eastern and southeastern United States, with the highest concentrations occurring in Ohio (where over 10,000 have been located). They are of very different sizes and shapes, and do not belong to a specific culture, but were built by different peoples and different functions. Some had funerary purposes, others were defensive and there are some that are the base of ceremonial centers. The oldest are from the second millennium before our era and were made of mud and shells; the most distant date is held by the so-called Poverty Point (Louisiana), dating from 1500 BC. c.; on the contrary, the later mounds stopped rising with the arrival of the Europeans, in the 16th century, almost all belonging to the Mississippi culture. This is one of the three most important towns, which follow one another almost without breaks:

- Adena culture: it is given in the Ohio River valley between 1000 and 200 a. C. Adena built funeral mounds, i.e. tumulus. In them, the remains were deposited in small mortuary wooden chambers, after having left the bodies at the mercy of the vultures (it is usually known as secondary burial and given in many cultures); the rinse was composed of animal figurines and other objects. They also raised what is known as mounds-efigie (Effigy Mounds), that is, with concrete forms. The most famous is the Serpent's Montcle, whose sinuous shape of more than 300 meters in length, begins in a spiral and ends with the head in which it seems that there was an altar.

- The hopewell culture (200 B.C.-500 AD) is a direct successor to the adena, so they look quite alike, although its mounds are larger and its most advanced and rich material culture. They build huge funeral tumults and effigy mounds in the form of birds, bears, men, etc. Among the objects found in the inhumations are the pieces of mica. obsidian, bear fangs and hammered and replenished copper objects. They also have a rich ceramic and clay figurines.

- The mysisipi culture: it was given between 500 and 1500 AD in a vast territory of the southeast covering from Tennessee to Oklahoma, although its peak period was given in the 13th century, it is sometimes also known as a culture of the Natchez Indians. Its nerve centre was the city of Cahokia (San Luis Este, Illinois), which itself was a huge elevation that housed more than 30,000 people. He was heavily protected and inside there were numerous mounds called monks. it was, possibly, of places of worship, with the flat top, where it rose, at the time, some temple. One of those monks was of enormous dimensions (300 meters in length for 30 meters in height) and had several temples at the top of his terrace, some of great size.

It is assumed that Cahokia had a complex social hierarchy, with a tribal chief and a powerful caste of priests (there were also military chiefs, warriors and, below, the common people). One of the tombs found seems to have belonged to a high priest (called a bird-man), as he rested on a bed of thousands of pearls and other typical Cahokia objects, such as solar discs and crosses engraved on shells and stones.

The Monumental Art of the Northwest Indians

On the North American Pacific coast, a series of tribes survived which, until the XIX century, lived off resources sailors and that, although they did not come to constitute a culture of greater complexity than the tribal one; Thanks to the abundance provided by their economy, they were able to develop their well-known ceremonies called potlatch and an art of considerable magnitude. This was based, fundamentally, on the polychrome wood applied both to the totem poles and to the decoration of communal and ceremonial dwellings. Since these peoples were semi-nomadic, some of these dwellings were designed to be disassembled and transported, despite their complexity. In the totem poles, in addition to recording the tribal lineage (generally related to the animal world), a highly original colorful and expressionist plastic was displayed by combining and dissociating its elements from the pole in an almost organic way.

Today there remain in North America "pockets" of indigenous culture as rich and numerous as its members are few. But, although they retain much of the traditions of their ancestors, in them it is impossible not to see the growing weight of Western influence. This does not detract from their artistic manifestations, even though after centuries of Europeanization they are somewhat syncretic or mixed. However, these towns must be studied under a heading appropriate to current primitive towns, not to prehistoric towns.

Latin America until the formative period

From the period in which ceramics, agriculture and livestock were already known, we have very few data on the origin of the first great classical Mesoamerican culture, the Olmecs. There is no comparable previous culture, although it is suspected that a long period of abundance could give rise to the birth of this civilization. The closest precedents would be in the adobe pyramid of Cuicuilco, in the Matanchén bay, in the Capacha culture, in certain sites of the Veracruz Huasteca and in the first phases of Tlapacoya.

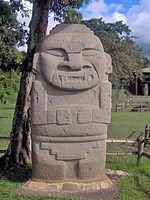

A little further south, on the Isthmus of Panama and in Colombia, important ancestral cultures of the Chibchas seem to have developed, especially the San Agustín culture, and the Valdivia culture in Ecuador. Although the first city worthy of being called that in South America is the great sanctuary of Caral (Peru), inhabited in a period that includes 3400 B.C. C. and 1600 B.C. C., that is to say, before, even of the knowledge of the Andean ceramics. This great ceremonial center demonstrates important architectural knowledge, the most important buildings being the 32 pyramidal structures, numerous open spaces for large gatherings (called amphitheatres) and several temples with their characteristic "U" plan, among which the so-called "altar of the Holy fire". It is assumed that Caral would be the center of a homogeneous culture, perhaps an authentic centralized state, based on religious cohesion, since other secondary cult centers have been found in its area of influence, but of the same type (Caral, Chupacigarro, Miraya and Lurihuasi), so one could speak of the Caral-Supe culture, born in the “late pre-ceramic period”.

From 1500 B.C. C. would begin the "initial ceramic period" in which to the ceramic forms must be added the first representations of the feline god, or god-yaguar, which will become a constant of Andean prehistoric cultures. In this way, in the second millennium some characteristics typical of the Andean idiosyncrasy have already emerged, the great truncated pyramids, the cult of the Jaguar, the "U" shaped temples, etc.

The last great Andean prehistoric culture of the Chavín culture, from the formative period (between 800 and 200 BC). Once again, we would be facing a possible theocratic state with its capital in a large ceremonial center, the Chavín de Huántar, associated with the cult of the aforementioned jaguar-god. Its economic prosperity was based on numerous agricultural innovations, and its art is much more evolved, and the ceremonial enclosure stands out for its emblematic buildings, especially the so-called Castle, a complex with a Cyclopean rig, built over several centuries, with several terraces., patios and interior routes through countless labyrinthine corridors that led to a central room supported by the so-called "El Lanzón monolithic" (a kind of stone pillar, 4.5 meters high, decorated with the head of a man-jaguar of huge jaws, with curly hair, formed by intertwined snakes). Outside we have the "Estela de Raimondi" (3 meter high tombstone and a variegated design). Lastly, the Tello obelisk (decorated with a kinky beast-man motif superimposed on other hybrids of birds, fish and reptiles); more slabs with similar reliefs are scattered around the area.

Parallel to the Chavín culture, others run in South America such as Paracas, the first phases of Chanapata and Pucará (in the south-central Andes), and Chorreras (in Ecuador).

Asian

There is various evidence of prehistoric art from the Paleolithic, one of the most significant is the Venus of Berejat Ram, discovered in the Golan Heights.

Europe

From the news we have so far, the art was born in Western Europe more than 30,000 years ago and developed especially during the Upper Paleolithic in France, Spain and other countries, with a prodigious quality. However, at the end of the last ice age and the beginning of the Holocene period, for totally unknown reasons, the almost total disappearance of European art took place, so that it could be said that the clock was reset and synchronized with the rest of the world. carrying, since then a parallel development. In this article it has been decided not to include the art of the Iron Age in Europe for two reasons: the first is that the extension would be excessive, the second is that most of the European cultures of the Iron Age are Protohistoric or, even historical, and of most of them we have direct or indirect written news.

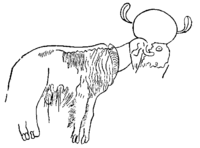

European Paleolithic Art

The Franco-Cantabrian school of art is the most important of all those that developed during the Upper Paleolithic in Europe, from approximately 35,000 years ago to about 10,000 years ago. Rock art, both parietal and movable, appears above all in the caves of the Spanish Cantabrian coast (Tito Bustillo in Asturias, El Castillo and Altamira in Cantabria...) and the south of France (Lascaux cave or Font-de -Gaume...), although it actually extends to other European regions (albeit with less density). Examples of this are the center of the Iberian Peninsula, with caves such as Los Casares, Maltravieso and open-air complexes such as Siega Verde. The technique used is painting, engraving, relief and, in the case of furniture art, the production of statuettes and other figures. The paintings are monochrome or bichrome (that is, more than two colors are never used simultaneously), although the color of the rock is used as a chromatic complement. Gradients are used to give a sensation of volume (modeling and shading) or protrusions of the rock are used. It is an animalistic art in which the human figure is relegated to the background; abstract signs or schematizations of sexual organs also abound. It is considered fundamentally descriptive, that is, there are rarely scenes (and when they are, they are probably not real events, but symbolic, that is, mythograms), the composition of the figures is juxtaposed, with a more symbolic than real meaning, and without giving the sensation of a natural movement (although this is expressed through certain conventions); Despite everything, the figures are very realistic and detailed, thus being an exceptional case in prehistoric art.

The function of Paleolithic art is totally unknown. At first it was thought that these works of art were made only for aesthetic reasons (to decorate: art for art's sake), and although no one denies the high aesthetic sense of these representations, this seems to be a secondary factor. Undoubtedly this art was of a magical or religious nature. No more details can be made, at best, several theories can be formulated, but without definitive proof. The most common proposals are totemism, shamanism, propitiatory magic, fertility and the dualism of nature. In reality it is possible that all the theories have some truth, that only taking them all together can the meaning of Paleolithic art be interpreted.

European Neolithic Art

Neolithic furniture art

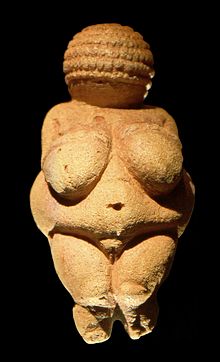

Neolithic furniture art (from 8000 BC onwards) includes a wide range of ceramic forms and other everyday objects, in addition to ornamental and ceremonial items, which were extensive in this phase. Ceramics have innumerable variants (depending on the morphology and the printed, incised or painted decoration), therefore, in order not to extend ourselves, we will only cite two of them: firstly, cardial printed ceramics, typical of the oldest phases of the Neolithic in the Mediterranean and characterized by decoration based on impressions made with mollusk shells; Secondly, we will mention the banded pottery, which occurs in the heart of the continent and whose decoration is incised with geometric motifs in the form of ribbons with whimsical curves. In southeastern Europe, painted ceramics predominate, due to oriental influence. The sculpture has an early and original development, in fact in practically all the Neolithic cultures of Eastern Europe appear, from the first stages, female figurines, normally of baked earth, but also of stone, which are supposed to represent the Great Mother Goddess of fertility (remarkable cases are those of Khirokitia in the ceramic Neolithic of Cyprus, in Sesklo and Dímini (in Greece), and above all, in the cultures of Vincha, Serbia, Cucuteni or Hamangia, in Romania). A special case is the stone sculptures of Lepenski Vir (Serbia), roughly carved on large pebbles with characters so peculiar in appearance that they have been interpreted as hybrid beings (half human, half fish).

- In terms of the scope of the ornaments, these are usually schist bracelets in the form of a ring, necklace beads of various materials (stone, bone, shell...), pendants made with bone, or with animal fangs, figurillas and practical useful objects decorated, almost always with abstract motifs. At the end of the Neolithic appear the first ornamental objects made of martilled native copper.

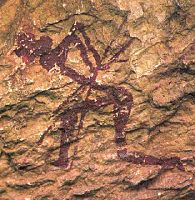

Levantine art

The school of Spanish Levantine art, which, for some scholars, must be dated to the Epipaleolithic (or Mesolithic) period, from 8000 B.C. C., and not in the Neolithic, attributing this last dating to erroneous and unfounded interpretations. The abundance of hunting scenes with their multiple and subtle aspects are more typical of a hunting people and not a cattle breeder.[citation needed] However, many specialists choose to locate them, in a very broad sense in older periods of the Neolithic since, indeed, their representations include certain cave scenes of livestock; In addition, some objects represented allow us to suppose that the paintings date from 8,000 to 5,000 BC. C. They are mural paintings that appear on the rocky cliffs and shallow caves of mountains and steep areas of the Spanish Mediterranean provinces (the Spanish Levante), from Lleida to Andalusia, highlighting Cogull, Alpera and Valltorta (among many others). We know of no associated furniture art, only wall paintings with crushed natural pigments. The main theme is the human being and his daily tasks: scenes of livestock, hunting, ritual dances or even violent fights. The style is very spontaneous and lively: the characters form real lively and dynamic scenes. The figures are stylized and monochrome silhouettes, that is, painted in a single color (red or black), they are flat and without modelling.

The megaliths

The megalithic phenomenon could be considered the first monumental architectural manifestation in Western Europe. Its birth seems to take place at the end of the fifth millennium in several simultaneous foci along the Atlantic, from Huelva (in Spain) to the Shetland Islands and Jutland, and its chronology far exceeds the Neolithic phase, surviving during the Bronze Age. especially in the north (logically there is also an evolution of the constructive forms). A megalith can be defined as a construction of gigantic stones (megas: giant and lithos: stone), roughly worked. Although in later periods the typology diversifies, during the Neolithic there are four classes of megalithic monuments: the menhir (which is nothing more than a large uncut stone driven into the ground), this can appear isolated or in large rows. Sometimes it also forms circles, then receiving the name of cromlech (in the metal ages, these stone circles become highly developed in the British Isles, receiving the name henges). In any case, the menhirs, isolated or in groups, would mark open-air sanctuaries. Finally there is the dolmen: a collective megalithic tomb that at least consists of a burial chamber covered by a burial mound, which has often been lost (this scheme is the most common, but more complex or simpler variants can be found). The burial chamber used to house the remains of a multitude of corpses along with their grave goods.

The decoration of the megaliths is usually abstract, although, since some seem to have a long life as sanctuaries, they also have figurative themes of a schematic type. There are three large nuclei where decorated dolmens stand out: Brittany (for example, the Barnenez and Mane Kerionez dolmens), Ireland (with New Grange or Loughcrew, among others) and, of course, the Galician-Portuguese area in the Iberian Peninsula (with Antelas and Padrão in Portugal; the Farm of Tininuelo and El Soto in Spain). The first decorative phases tend to be abstract (culvilinear and geometric shapes, domes), sometimes engraved and sometimes painted. Over time, recognizable schematic forms appear (weapons, anthropomorphs, zoomorphs...). The chronology of this decoration seems to be Neolithic, however, in some representations it is possible to recognize metallic objects, with which it is necessary to assume a long chronological survival.

Associated with megalithic monuments, but located in rocky areas of the Atlantic coast, from the mouth of the Tagus, in Portugal, to the Orkney Islands in Great Britain (passing through Galicia, France and Ireland) we can include the Atlantic petroglyphs. Its theme seems to be the same: curvilinear motifs, meanders, domes, spirals, labyrinths, squares... (rarely with anthropomorphic or zoomorphic representations), but its heyday occurs in the second millennium BC. C., that is, the Bronze Age. It is not uncommon for this type of manifestation to survive later phases, as occurs with the British henges. This decoration must have a strongly symbolic value, representing concepts whose content escapes us.

- Petroglyphs of the Atlantic Cornisa of Europe

European art in the Metal Ages

The schematic cave phenomenon in Europe

The arrival of metal coincides, at least in Europe, with a radical change in the style of rock painting. From Paleolithic descriptive realism and Levantine narrative stylization, we move on to an eminently symbolic schematism. The shapes are reduced to their most essential features, without ceasing to be figurations of real elements (abstraction is not reached except, as we will see, in the westernmost area). Schematic rock art is highly developed in the Iberian Peninsula, both in painting and in engravings, but it also extends throughout the Atlantic fringe (from Portugal to Norway), but it is also particularly abundant in eastern France and northern Italy (both in the Atlantic, and in the Franco-Italian area, engravings predominate, that is, petroglyphs), The development of schematism in prehistoric art has been interpreted as a liberation from reality, as a triumph of the symbolic world and Therefore, it would be a consequence of the appearance of much more mature religions. Apart from this, the improvement of metallic tools favors the work of the rock, and therefore the inscultures are gaining importance, to the point that the Nordic petroglyphs continue to be made to historical periods.

- The Scandinavian province has greater density in the south-central Norway and Sweden, in the regions of Escania and Upsala; highlighting the area of Tanum (declared a World Heritage Site (with more than 300 sets of rock art). Scandinavian engravings usually appear on rocks smoothed by glacial erosion, are of great size and their main themes are warriors and ships. Scandinavian petroglyphs arise at the age of Bronze, around 1600 B.C. and last until the year 100 of our era.

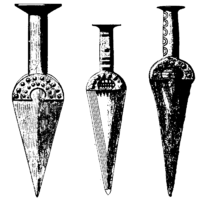

- The province of the French-Italian Alps is one of the world's first known areas of rock art. Specifically, in the Italian region of Lombardy, the petroglyphs of Val Camónica were also declared a World Heritage Site. The majority are of the Bronze age, although they survive until the Iron Age. There are many themes, but the predominant ones are deer hunting, human figure and astral signs. In the Maravillas Valley (Alpes Marítimos, France) the protagonist is the bull in several typologies, although he highlights an expressive character armed with two daggers known as "the sorcerer". Precisely, the weapons represented allow us to calculate a main dating in the Old Bronze, although later other cultures are added that reach the Iron age.

- The schematic art on the Iberian peninsula: the entire peninsula has schematic rock art deposits, although, to be more concrete, this predomine in mountainous areas where there is availability of rocky coats (nevertheless, it has non-ropestres parallels in llanes areas, reflected in decorated ceramics, furniture art, decoration of megaliths, etc.). Nevertheless, it would be a mistake to consider it a unique phenomenon; rather, we should talk about numerous different regional cultures. In any case, the rise of the schematic phenomenon corresponds to the third millennium B.C., above all to the Calcolytic, beginning its decline in the age of the Bronze, although there are many more later pervivences.

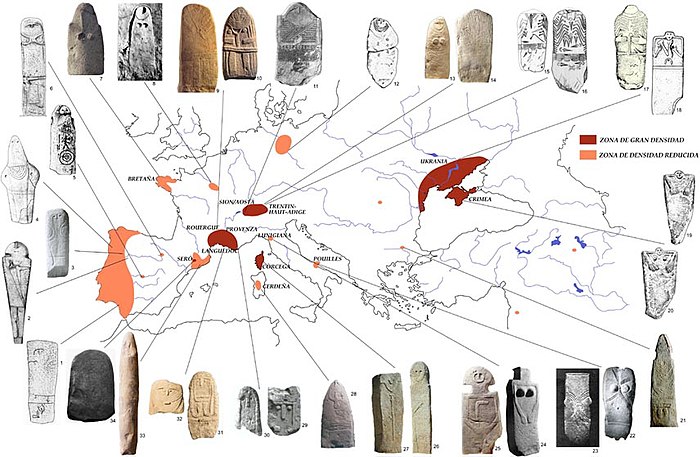

The sculpture

The monumental sculpture is directly linked to the Neolithic works that we have mentioned about the Mother-Goddess, in fact, in some tombs there are crude female characters carved on their walls, such is the case of the sepulchral grotto of Coizard (Marne, France) that follows identical models to the so-called menhir-statues, dating from the end of the Neolithic to the end of the Bronze Age). They are monolithic, solid, roughly hewn figures, of considerable size, on which very simple human features have been drawn by means of incisions or, at most, bas-reliefs, standing out on the head, the so-called "owl eyes".. The trunk is not differentiated and the extremities appear only on a few occasions. The block is usually furrowed by linear decorative motifs and signs about the character's sex and condition (necklaces, weapons, tools...). They appear above all in the southeast of France, in Italy, in Corsica and in the Iberian Peninsula.

The oldest seem to be those of the Italian Provençal Neolithic (beginning of the 3rd millennium BC), where no relationship with the megalithic world could be established, although they appear associated with burials. As of 2500 B.C. C. extend to the southeast of France, to the area known as Rouergue (Aveyron and Hérault), where they acquire their full development, highlighting the so-called "Lady of Saint-Sernin", discovered in 1888. The statues already appear from the metal age -Ligurian menhir (Italy): based on the weapons they carry, a long sequence can be established that begins in the Chalcolithic (Pontevechio type), continues with bronze (Canosa type) and culminates in the transition to the Iron Age (type Remedello). In Corsica we have a similar succession, some of these works are associated with the horizon of the nuraghes, born at the end of the Bronze Age although it culminated in the Iron Age.

They appear in the Iberian Peninsula (especially in Extremadura and the surrounding regions), but they probably belong to an independent and later group, at least in origin, since they are not associated with dolmens, although they are also funerary. They are typical of the Full Bronze Age and, in their late phases, they already represent warriors with radiated helmets and a complete panoply made up of a dagger, sword, halberd or spear and shield (fibulas, mirrors..., sometimes, also, battle chariots).

The architecture

The civil architecture of primitive Europe of the Bronze Age can be separated into two large groups. In the continental and Atlantic zone, wooden towns and villages predominate, with individual houses, also made of wood, and a protection made up of a palisade. At first such protection was more focused on cattle, but over time it had to be reinforced, due to the increase in attacks between neighboring communities, adding walls, moats and several belts of walls made of logs and mud (eg Karanovo, Goldberg, Tripoljé...). The exception to this pattern is the Skara Brae site (in the Orkney Islands). Skara Brae has barely a dozen semi-subterranean houses with a rounded shape, built in almost cyclopean stone ashlar. This enigmatic coastal village was abandoned and hardly any objects are found among its ruins, making it difficult to date, although it is estimated that it was inhabited in the third millennium. Mediterranean Europe has very different towns, perhaps due to oriental influence, they surround themselves with thick stone walls endowed with semicircular defensive towers. Inside the powerful enclosure, the adobe houses huddle together, without a concrete organization. They also usually have a citadel with specially reinforced fortifications. The most impressive examples of this type of settlement are Sesklo or Khirokitia (in the Aegean), Los Millares (in Spain), Zambujal and Vila Nova de São Pedro (in Portugal); all of them cacolithic. During the Bronze Age, fortifications were perfected and the use of stone spread throughout the rest of Europe, probably thanks to new tools. The Stage culminates in the Iron Age with an entire continent littered with fortifications or towns with strong fortifications complemented by towers, moats and fields of sunken stones.

Religious architecture is characterized by the survival of megalithic or cyclopean constructions. In the third millennium, it is necessary to emphasize the importance of the set of temples of Mudajdra, Tarxien and Ggantija on the island of Malta (semi-subterranean and topped with huge stone slabs, they contained gigantic female statues dedicated to fertility; but they must also have funerary function, because in one of them, Ħal Saflieni, remains of thousands of corpses were found). Some dolmens survive in the Ancient Bronze Age in which the false dome cover is already developed (the arch or the authentic dome are not known). In the late Bronze Age, with the arrival of the complex of cultures of the burial mounds, funerary customs changed, from collective to individual, but certain areas conserved megalithic cult centers, such as the henges or circles of stones in the British Isles (the best known and most spectacular example being Stonehenge, reformed over and over again from its founding around 2700 BC to its last phase in 1500 BC or so). In the Scandinavian area and northern Germany, the boat-shaped tombs from the Late Bronze Age stand out. Finally, highlight the Cyclopean ceremonial centers of the Mediterranean, from the second half of the second millennium, in the Late Bronze Age: we are referring to the buildings of the Talayotic Culture (phase I) in the Balearic Islands and the Nuragic culture of Corsica.

The development of metallurgical art

Copper, along with gold, are the first metals used; at first, both were obtained from nuggets and cold-hammered. Over time they went on to be cast and forged in the furnace. But copper is difficult to work with and not very resistant, so the first decorations are extremely simple (pins, mainly). Gold could be worked more easily and, from the beginning, embossed or cast ornaments appear.

The appearance of bronze (copper with 10% tin) represents an important step forward, as it is more versatile (melts at a lower temperature, cools very slowly) and allows more complicated objects to be made. As the Bronze Age progresses, the techniques become increasingly refined, but require not only a specialized craftsman (often accorded special treatment), but a continual supply of raw materials, often in turn, stimulates commercial and cultural exchanges on the continent. The most active center is the eastern Mediterranean, but we have already seen that there are important cultures in the Atlantic, in the Baltic and in other European regions. Weapons (swords, axes, armor...) go beyond their warlike role to become prestigious or ceremonial objects, which is why they are sometimes decorated as authentic jewels, to which other objects of body adornment (brooches, bracelets, torques, lunulas...) and purely ceremonial and votive objects.

The end of Prehistory in Europe

The «swan song» of European Prehistory is marked by the penetration of the people of the urn fields, whose impetus led to the destruction of ancient European traditions, being responsible, even, for the decline of Mycenae. Only the Atlantic strip was able to resist his push. These towns, in turn, to the first culture of the Iron Age: Hallstatt. Based on their technological superiority and the use of light cavalry, they occupied almost all of Europe, creating a new order that, after a dark period due to conflicts, led to the birth of the great classical civilizations (Etruscans, Greeks, Romans, etc.)....) and Celtic, to which should be added Tartessos, in the south of Spain, more linked to Orientalizing culture than to Indo-European. All these towns end up entering the so-called ancient European history.

Oceania

Obviously, considering Oceania as a geographical entity is a mere convention given the enormous cultural diversity and the vast geographical area it covers (the largest on the planet), dotted with hundreds of archipelagos. If we except Papua New Guinea, this area was not inhabited by humans until the appearance of Homo sapiens. Precisely this large island, Papua New Guinea, seems to be the springboard from which Australia, Melanesia, Micronesia and Polynesia were occupied by sea. However, while it is plausible to think that all these areas were occupied, more or less, simultaneously, Australia does have very ancient remains (dating back to the Paleolithic, over 40,000 years old), while the archipelagos of the rest of Oceania only preserves archaeological remains of peoples who practiced agriculture (yam, taro, breadfruit, banana...) and livestock (pigs and chickens...). We are therefore talking about the Neolithic, with polished axes and pottery with very recent radiocarbon dates: 1500 B.C. C. for Micronesia (in the Mariana Islands); 500 B.C. C. for Melanesia (in New Caledonia) and 125 a. C. for Polynesia (in the Marquesas Islands).

Artistic diversity is also considerable, but all traditions share the high social status held by artists and the role their works play in maintaining social cohesion. Indeed, the sacred nature of the works persists to this day and, with it, numerous taboos that, in general, maintain tradition, impede evolution and sometimes make us face excessively stereotyped and conventional manifestations.

Australia

We will deal here only with Australian Aboriginal art that predates colonization and that, despite being (probably) the first land settled in Oceania by modern humans since Papua New Guinea, remains in its most primitive forms. Australian aboriginal art is fundamentally rock, it is about natural sanctuaries decorated with paintings and engravings, but there are numerous ritual objects that can be associated with the ceremonies carried out in them. Cave paintings are quite conventional and schematic (reaching geometric simplification), but they are also very colorful (one of the most striking conventions is the so-called "X-ray vision" with which some figures are represented). Furthermore, not only symbolic and mythological scenes were painted, there are others with a great narrative sense that can be considered real episodes or, more often, dreams. On the other hand, Australians also practiced body art, sand painting and decorated their boats with engravings and made ornaments on shells. Among their ritual objects, certain oblong plates, called churingas, which, attached to a rope, were rotated to emit a continuous buzz (they are often called bramaderas), stand out. A similar function was fulfilled by the dijiridús, huge wooden trumpets that emitted a rhythmic sound, not a melodic one, which undoubtedly combined with the hum of the churinga and helped to create a propitious environment for the union ceremony with the totemic ancestor.

The most representative places of Australian Aboriginal art are Bradshaws, in the north of Western Australia; the Carnavon Gorge in Queensland; the banks of the Kakadanu in the Northern Territory and, above all, the natural monolith of Uluru, popularly called Ayers Rock, the red mountain, in the south of the Northern Territory, almost on the border with South Australia, next to Alice Springs, that is to say, practically in the geographic center of the island-continent.

Melanesian

It is the set of islands located to the north and northwest of Australia, highlighting above all that of Papua New Guinea, although the set of other archipelagos exceeds well over ten. On the other hand, the Melanesians, contrary to what was believed until recently, do not constitute a Negroid racial unit, but their linguistic, cultural and genetic diversity demonstrates a great variety of peoples. In general, the primitive Melanesians used to be animists, and believed that people's souls were reincarnated in several objects simultaneously, which favored artistic creation, understood as the creation of religious objects (statues, masks, masts, malagnaes, drums....) of great diversity and richness. At the same time, the early Melanesians were quite territorial, even hostile to their own neighbors, so they did not go beyond the tribal structure into small communities, each with its own traditions. There are numerous artistic centers in Melanesia, but we will highlight the Sepik River Valley on the island of New Guinea and the Vanuatu Islands.

Apart from the body adornment, based on tattoos, scars, piercings, paintings and feathers in vivid colors, one of the most notable elements of Melanesian art are the great meeting houses or "houses of the spirits", exclusively for men and that are usually dedicated to ceremonies related to the cult of ancestors. These constructions are very diverse in typology depending on the region or the island, but, in general, they consist of a single room, with a very steep gabled roof and a richly decorated façade. The door is usually very narrow and forces you to enter on all fours and go through a kind of maze. Inside, the richest works of art, of religious significance, accumulate: especially sculpted flagpoles, masks and the Vanuatu malaganes, large polychrome wood carvings that were shown to the tribe only on special occasions.

Micronesia

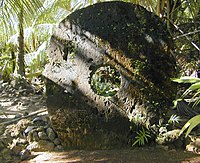

These are six archipelagos of coral origin that in prehistoric times were under the influence of the Polynesians, but in historical times fell under Malay control. Micronesian art is the simplest in Oceania, carvings are scarce, except for the case of canoes, they are also great artisans in making mats, with geometric motifs, sometimes abstract or, sometimes, stylizations of anthropomorphs and zoomorphs of Polynesian inspiration. But Micronesians are not without certain original aspects. For example, the so-called "coin-stones", large perforated stone discs that were moved from remote areas to the entrance of the homes of the most powerful to demonstrate their socioeconomic status. Another interesting example is that of Nan Madol, a large ceremonial capital with impressive Cyclopean architecture built between the 8th and 12th centuries AD.

Polynesia

Polynesia is comprised of twenty archipelagos in the South Pacific, with a great cultural richness due to the successive waves of colonization that its islands suffered. Polynesians, much lighter in complexion than Melanesians, are noted for their extraordinary seamanship and desire for peaceful relations with other peoples (unlike Melanesians), and are much more receptive to news, which made them more permeable to other cultures and makes their traditions more homogeneous. On the other hand, the lands inhabited by the Polynesians were unsuitable for agriculture (except for certain fruits and spices) and livestock (except for pigs), on the other hand, they were rich in fishing. The Polynesians developed, then, a great shipping skill based on canoes and catamarans of various sizes, depending on the distance to which they were intended. Such vessels, some of which reached 30 meters in length, had a richly carved decoration on the prow, especially, and mat sails (made of tree bark and called "tapas") woven with geometric motifs that reached be true masterpieces. Despite the geographic enormity of Polynesia, we will focus on three areas for this brief review, New Zealand, the Society Islands, and Easter Island.

New Zealand

The settlement of these islands is very late, beginning in the 10th century and culminating in the 13th century. In fact, the first Europeans collected oral traditions that spoke of this colonization coming from central Polynesia; therefore it is very recent. The Maoris formed a relatively wealthy culture thanks to the island's resources, which is why they are one of the most artistically developed peoples in the Pacific. Its architecture is based on the use of huge kauri pines with which they built the "mara'a" or large 'meeting houses' of Melanesian inspiration, although their access was not so restricted. These rectangular houses, with a gabled roof supported by richly carved posts, had a monumental façade with an extraordinary carved and polychrome decoration on Maori mythology: the lizard as a symbol of evil, the fish-man or marahika, the whale and many other creatures among motifs of spirals and meanders. In addition to the house, the Maori also decorated their barns in a similar style. In both cases we are talking about highly refined constructions whose meaning transcended the religious to also become symbols of wealth and power. Something similar could be said of their enormous canoes, for which they chose the largest trees, since they were carved in one piece, except for the decorated prow, which was added later.

The Maori are also known for the art of tattooing, which was combined with scarification to obtain raised effects on the skin. Women only tattooed on their lips, but men tattooed their entire face, torso, and extremities, with designs that were never repeated. Another characteristic of the Maoris was the manufacture of jade amulets or "tikis", in the shape of anthropomorphic monsters of exquisite finish.

Hawaii Islands

The Hawaiian population had a first Micronesian colonization to which were added successive waves of Polnesian that did not stop until the 13th century. The two most original aspects of Hawaiian art are undoubtedly the creation of beautiful headdresses of multicolored flowers and feathers and the carving of idols with disproportionate heads and terrifying expressions. They could be protective divinities or common ancestors. Finally, the Hawaiians built numerous open-air rock sanctuaries with altars and engraved decoration, that is, petroglyphs, throughout the island.

- Artistic manifestations of the primitive Hawaiian art

Easter Island

The artistic manifestations of the island of Rapa Nui are among the most original and controversial, not only in the Pacific, but in the entire world. An island of 163.6 km², 2,000 km from the nearest island and almost 4,000 km from the mainland, which European explorers did not find until the 18th century, almost uninhabited, with no other vegetation than herbaceous and with about five hundred colossal heads de piedra has provoked rivers of ink and countless explanations, some more sensible than others. Apparently, La Pascua was occupied by Polynesians from the Marquesas Islands at the time of maximum migratory movement in the area, that is, the 13th century. At that time it was covered with forests, which led to the flourishing of a highly stratified culture with a very powerful priestly caste. The abundance of resources favored enrichment and this, in turn, led to the construction of innumerable sanctuaries scattered throughout the coastline whose greatest manifestation were the moai: heads up to 10 or 12 m high and weighing 50 t, which would represent mythical or deceased ancestors. Today there are various theories but none fully explains how the moais were made, it is not known how they were extracted from the quarries or how they were modeled, although it is thought that they were transported by sleds, it is very difficult imagine how they could be erected and completed with a stone headdress, like a hat, and how the eyes embedded in white stone were placed.

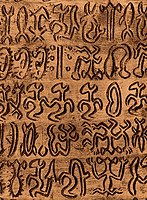

The moais had their backs to the sea on platforms that acted as temples in the open air, their faces are polyhedral, with deeply sunken eye sockets, a very protruding forehead and a disproportionate nose (features that would be softened by placing the eyes). But the people of Easter Island have other artistic manifestations, such as the petroglyphs of Orongo, related to the myth of the Easter egg and the ceremony of the bird-man or Tangata Manu; and the rongo rongo, or tablets with signs that could be a primitive form of writing (something unknown to the other oceanic peoples).

Contenido relacionado

Heroes of Silence

Pedro de Heredia

Mozarabic