Portugal's flag

The Portugal flag is made up of a rectangle divided vertically between green, attached to the mast, and red. On the border between both colors is a simplified version of the national coat of arms (including the armillary sphere). It was approved by the Portuguese Assembly on June 19, 1911. Its official description appears in Decree number 150, of June 30, 1911, which is the norm to which the Portuguese Constitution itself refers to define it, replacing the standard used during the constitutional monarchy. The design was chosen among several proposals by a jury, in which Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, João Chagas and Abel Botelho participated.

The colors were all traditional, since they represented the dictatorship that brought together the monarchical and religious tradition of the country. After the failed republican insurrection of 1891, red and green became the colors of the Portuguese Republican Party and were associated with all the events that led to the Revolution of October 5, 1910 that established the republic. During the following decades, the colors were gaining popularity among the people, as the government tried to instill that these colors represented the hope of the nation (green) and the blood (red) of those who had lost their lives for the homeland. With these measures an attempt was made to give a more patriotic than political character to the flag.

The current flag constitutes an important change compared to the evolution that the national ensign had during the different stages of history, since until then it had been closely associated with the royal arms. With the founding of the country, the national flag was based on both the blue cross of King Alfonso I and the white background, which represented liberal ideology. The different events that occurred in the history of Portugal greatly affected the development of the coat of arms of Portugal, until reaching the current design of the main flag

Design

The decree that replaced the flag used during the constitutional monarchy was approved by the Constituent Assembly and published in the official newspaper number 141 on June 19, 1911. On June 30, 1911, they were published in the same newspaper (number 150) the official regulations regarding the flag.

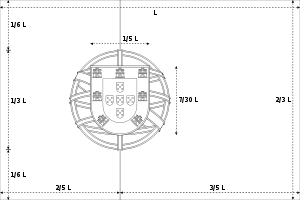

Dimensions

The length of the flag is one and a half times greater than the width, which translates to a ratio of 2:3. It is vertically divided into two fundamental colors: dark green, in the part closest to the mast, and scarlet red in the other part. The division by colors is such that green occupies two fifths of the length and red the rest.

A version of the Coat of Arms of Portugal without the laurel wreath — the national coat of arms surrounded by white on a yellow armillary sphere — sits on the border between the two colors. The armillary sphere has a diameter equal to half the width and is equidistant from the upper and lower points of the flag. It has five arcs representing the ecliptic, the equator, two Parallels (the tropics) and a Meridian. The inner shield has five small blue shields (shields or quinas) arranged in the shape of a Greek cross. Each one has five white coins placed in the shape of a Saint Andrew's Cross. In addition, seven yellow castles appear, of which three are in the main part.

The colors of the flag are not specified in any legal document; Some approximate colors appear in the list below:

| System | Red | Green | Yellow | White | Blue |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantone | 186 | 363 | 122 | Safe | 300 |

| RGB | 206-17-38 | 61-142-51 | 252-216-86 | 255-255 | 0-114-198 |

Origins

With the Revolution of October 5, 1910, the need arose to replace the monarchical symbols, represented in the first instance by the national flag and by the anthem. The choice of the new flag was not without conflict, especially with regard to the colors, since there were supporters of the republican red and green, while others advocated the traditional and monarchical blue and white. Blue also had a strong religious significance, as it was the color of Our Lady of the Conception (Portuguese:Nossa Senhora da Conceição), who had been crowned Queen and Patron Saint of Portugal by King John IV. In this way, the replacement of this color was one of the priorities of the Republicans, within the wave of secularization of the State.

After many discussions and with several flag models, a government commission was created on October 15, 1910, which included Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro (painter), João Chagas (journalist), Abel Botelho (writer) and two military leaders of the 1910 revolution – Ladislau Pereira and Afonso Palla. This commission chose the red and green of the Portuguese Republican Party, based strictly on patriotic motives. These colors had been present on the banners of the rebels during the republican insurrection of January 31, 1891 in Porto, as well as in the one that had place in Lisbon.

Regarding red, the commission considered that it should (...) be present as one of the main colors, because it is the warm and virile color par excellence. It is the color of conquest and laughter. A beautiful and fiery color (...) It recalls the idea of blood and urges us to obtain victory. As for green, it was more difficult to explain its inclusion, since it had not been a traditional color in the Portuguese flag during the development of the story. However, it was justified because, during the insurrection of 1891, green was the color found in the revolutionary flag that "shone on the redeemed lights" of republicanism. Finally, white (on the shield) a beautiful and fraternal color, for which the other colors can stand out, the color of simplicity, harmony and peace, adding that (...) it is the same color that, charged with enthusiasm and faith by the red cross of Christ, marked the epic cycle of the Age of Discovery.

The Manueline armillary sphere, which has been present on the national flag since the reign of John VI, was kept because it was dedicated to the Epic Portuguese maritime history (...) the ultimate challenge, essential for our life collective. The shield was also added, but this time on the armillary sphere. Their presence represents the human miracle of positive courage, tenacity, diplomacy and audacity that made it possible to unite the first links of the social and political affirmation of the Portuguese nation, being this one of the most vigorous symbols of national identity and integrity.

The new flag was produced in large quantities at the headquarters of the Cordoaria Nacional (national rope factory) and officially presented throughout the nation on December 1, 1910 (day of the Restoration of Independence), which had previously been declared by the government as Día da Bandeira (it is not currently celebrated). In the capital, it was moved from the Town Hall to Praça dos Restauradores, where it was hoisted. This festive presentation could not calm the voices against a flag that had been adopted without prior consultation with the population and that represented the political regime instead of the nation. To increase the esteem towards the flag, the government ordered that it be exhibited in all educational centers, having to explain its symbols to all students; the textbooks used in the schools were reformed so that the new national symbols appeared. December 1 (flag day), January 31 and October 5 were declared National Holidays.

Meaning

Colours

The flag probably has a much older meaning than the more traditional and popular explanations of its design. The most widespread belief, made explicit especially during the Estado Novo (the nationalist authoritarian regime that occurred between 1933 and 1974, when it was put to an end by the Carnation Revolution), says that green represents hope and red the blood of those who have given everything for the nation. This definition of colors is currently the most accepted, although the original meaning is rather uncertain.

According to other theories, red represents sunrise and sunset in the voyage of Portuguese ships during the Age of Discovery in the XVI, while green evokes the color of the oceans sailed by the great Portuguese navigators.

Lastly, another theory says that the red signifies the blood shed in the battles against the Saracens of the 12th-15th centuries and that the green represents the fields where these battles took place.

The Portuguese heraldic shield

The traditional Portuguese coat of arms has been present in almost all the flags that have followed one another. It is the original symbol of Portugal, one of the oldest national symbols still in use, and of course one of the oldest in Europe. Used over 800 years ago, it appears on all but the first flag. The shield, in fact, has its roots in the first flag (1143-1185) and the first king of Portugal.

The five white dots (besantes) of the five escutcheons in the center of the flag refer to a legend related to the first king of Portugal, Alfonso I. According to this, before the battle of Ourique (July 26, 1139), King Alfonso prayed to the Portuguese people when Jesus appeared to him on the cross. The king won the battle and, as a token of gratitude, incorporated the five wounds of Christ (the stigmata) into his banner. This myth, similar to the one that occurred with the Roman Emperor Constantine, seems to have been forged to obtain the recognition of the Portuguese king by the Holy See. According to another legend, the escutcheons would represent the five Moorish kings defeated in the aforementioned battle.

The castles, which originally numbered nine, are a symbol of Portugal's victories over its enemies during the reign of Alfonso III. They would make reference to the nine Saracen castles taken by the Portuguese troops in 1249; Furthermore, the castle was the emblem of the Kingdom of the Algarve, the last to be conquered by the Portuguese, when the borders were definitively defined. Later, King John II reduced the number of castles on the flag to just seven.

The Armillary Sphere

The circular drawing is an armillary sphere that replaced the crown of the old monarchical flag. It represented the Portuguese Colonial Empire at the time of the Revolution and at the same time the discoveries of Portuguese navigators throughout the world. It was the symbol of Manuel I the Fortunate (1495-1521), who reigned during the period considered Portugal's greatest strength. In addition, the armillary sphere was also a symbol that was frequently used on the pillories that presided over public squares (the so-called pelourinhos). This sphere has 5 arcs that represent the Earth's equator, as well as the meridian and two parallels.

The sphere was first introduced into the flag by John VI (1816-1826) as a symbol of the Kingdom of Brazil when he declared this country one of the kingdoms of the United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and the Algarve. It was removed from the flag after the king's death, since during his reign Brazil had achieved independence. The fact of removing the armillary sphere from the flag was one of the testamentary wills of the king, rather than a maneuver of his son Pedro, the future emperor Pedro I of Brazil, in order to keep this territory within the family.

Evolution of the Portuguese flag

1095-1139/1143

The display of the flag was something relatively recent at this time. The flags derived from the coats of arms used by the feudal lords (the first coat of arms to become a flag seems to be that of the Kingdom of Jerusalem, by concession of Pope Urban III).

The coat of arms of the County of Portucalense was that of Count D. Henrique, which consisted of a simple blue cross on a white background.

The historicity of this flag is debatable, since many of its references arise in the framework of the great commemorations sponsored by the New Portuguese State in 1940, especially in the Exposição do Mundo Português.

1139/1143-1185

The first Portuguese flag was the one used by the first king of Portugal on his shield during battles. It was a blue cross on a white background, and it was also the emblem of his father Henry of Burgundy, Count of Portugal (1093-1112).

After the Independence of Portugal, although without historical evidence to corroborate such a theory, Alfonso I would have superimposed the bezantes (or monedas) on the blue cross of his shield, thus indicating that the owner of that The shield could mint money — a sign of a clear demand for autonomy against Alfonso VII. However, that was not the only reason: the bezantes offered greater solidity to the country's coat of arms. According to tradition, this inclusion of money would be related to the Miracle of Ourique, according to which Jesus Christ would have appeared to the first Portuguese king, giving him victory. In this way, Afonso Henriques would have included in his coat of arms the thirty coins for which Jesus was sold (or according to another theory, his five wounds). Note, however, that the supposed Miracle of Ourique was wrought centuries later by the monks of Alcobaça.

1185-1245/1248

In this period, the flag or banner continues to be a translation of the royal arms, which consisted of five shields on a silver field, arranged in a cross and the sides pointing towards the center. The five shields represent the five wounds that King Alfonso I received in the battle of Ourique, or the five Moorish kings defeated in this same battle, or even the five wounds of Christ already mentioned.

The successor of Afonso Henriques, Sancho I would replace the blue cross with five quinas of the same color. Tradition says that, of the coat of arms that Afonso Henriques received from his father, with a blue cross, to which he superimposed the bezantes, there remained only the sheets that represented the coins and small pieces of blue cloth glued to them, thus giving the impression of the five quina shields that the flag still has today. The blue cross would disappear, like this, definitely. There were five shields, placed in a cross, each one including an indeterminate number of bezants.

1245-1248 to 1383-1385

According to the heraldic practices of the time, since he was not the eldest son of Alfonso II, upon inheriting the throne from his brother Sancho II (by imposition of Pope Innocent IV), Alfonso could not use "clean weapons", this is, to use the shield of his father without introducing alterations. It is believed that the introduction of the gules border loaded with gold castles had to do with the fact that his mother (Urraca de Castilla) was Castilian or, less likely, influenced by his wedding with Beatriz de Castilla.

However, tradition established another story, corroborated by many chroniclers throughout Portuguese history (Duarte Nunes do Leão, Frei António Brandão, etc.) — that of the castles representing the fortresses taken by Alfonso III a the Moors in the Kingdom of Algarve. These thus represent the integration of the Algarve into the Crown of Portugal. These chroniclers refer to several castles, without specifying how many there were, citing those of Albufeira, Aljezur, Cacela, Castro Marim, Estômbar, Faro, Loulé, Paderne, Porches and Sagres, therefore, although they write at a time when The number of castles was set at seven, allude to a higher number. It was on this theory that the commission for the design of the new republican flag in 1910 was based, basing itself to justify the heraldic presence and the meaning of the seven castles on the border.

The exact number is unknown, either of the castles on the border, or that of the bezantes of the escutcheons.

1385 to 1475 and 1479 to 1485

With the accession to the throne of the Master of the Order of Avis, Juan I, there was a new bankruptcy in the dynastic continuity, since he was not the legitimate son of Pedro I; In this way, to distinguish himself from his predecessor (his half-brother D. Fernando I), he added the green fleur-de-lis, which was the symbol of the Order of Avis, to the national arms, leaving each of the four points visible on the embroidery of the castles

It is the first flag whose historicity is proven, all the previous ones are reconstructions. It is also at this time when the first references to the use of the term "quina" appear to designate the shields of national arms.

This flag would be the origin of the flag of the Salazar youth organization: the Mocidade Portuguesa.

1475 to 1479

In 1474, the King of Castile Enrique IV died. The king left his daughter Juana as heir, called la Beltraneja by her detractors, who supported the king's half-sister, Isabel as a candidate for the throne. Hoping to assert the rights of his daughter, the late king will ask his brother-in-law Alfonso V to marry his niece, as a way of legitimizing the weak position of his heir. In 1475, Alfonso of Portugal agreed and married Juana, adding to his title that of the crown of Castile (King of Castile, of León, of Portugal, of Toledo, of Galicia, of Seville, of Córdoba, of Jaén, from Murcia, from the Algarves from here and beyond the seas in Africa, from Gibraltar, from Algeciras, and the Lord of Vizcaya and from Molina) and also proceeds to change their weapons, displaying a shield divided into four quarters, with the arms of Portugal in the first and fourth, and those of Castile in the second and third. The following year, when he invades Castile and is defeated in the Battle of Toro, it is this flag that his hosts carry and it is this flag that Ensign Duarte de Almeida bravely defends, losing both hands in defense of the national standard. It is this flag that also accompanies the King of Portugal on his visit to France, where he desperately tries to get help from Louis XI to continue the fight against the Catholic Monarchs.

1479 to 1485

After the signing of the Treaty of Alcáçovas, in 1479, with the resignation of Alfonso V, in his own name and that of his wife Juana, to the Crown of Castile, the previous flag was used again.

1485 to 1495

A century before, Juan II had been responsible for the elaboration of a coat of arms as it is known today, in its general outlines. He was also the last Portuguese king to use an armorial flag. Thus, in 1485 (according to Rui de Pina's account in his chronicle of D. Juan II) he ordered the suppression of the fleur de lis from the Orden de Avis de la bandera (believing that it was outside the national identity that the shield of the castles and quinas began to transmit). He also established the vertical placement of the lateral corners of the shield, since the knocked down shields could be heraldically considered a sign of bastardry or defeat, which was not the case. Finally, he ordered the definitive fixing of the number of gold castles on the border at seven and of the bezants in each corner at five, arranged in an X (this last one was due, in part, to the great devotion that the monarch had in the five wounds of Christ). Despite this, his successor Manuel I would return to the old formulas.

1495 to 1521

Ten years later, Juan II is succeeded by his cousin, the Duke of Beja, Manuel I, who imposed changes to the flag to differentiate himself from his predecessor.

In this way, he placed the royal arms on a quadrangular white flag, definitively getting rid of the armorial flags. The shield was again loaded on the border with a number greater than seven castles (although there are also representations with seven), ending in the shape of a wedge or "pointed". In the same way it happened with the escutcheons inside. Finally, Manuel ordered that an open royal crown be placed on the shield, a symbol of the royal authority and of the centralization of the State that both he and his predecessor had carried out.

There are references to the fact that, during the reign of Manuel, due to the intense maritime activity, the flag of the Order of Christ was frequently used as the Portuguese naval flag, since this was the great order linked to expansion voyages.

1521 to 1578

With the accession to the throne of the son of Manuel I, Juan III, there were some minor alterations in the format and composition of the shield, following the humanist taste, typical of the time. The Iberian shape (semicircular) was established to close the lower part of the shield, accompanying the quinas with the same alteration (although it is usual in heraldry for shields as heraldic furniture to assimilate their shape to that of the main shield. It was in this reign that the number of castles definitely returned to seven.

1578 to 1580

Shortly before embarking for Africa and losing his life in the Battle of Alcazarquivir, Sebastián I of Portugal ordered an apparently insignificant change, but one of great political significance: he proceeded to replace the open crown with a closed royal crown. This small change symbolized the reinforcement of the royal authority through the conquest of Morocco and the obtaining of an imperial title, which symbolized the closed crown. In the same way, to the taste of the Mannerist era, an ogival shape was once again established for the shield. This seems to have been the first Portuguese flag with a rectangular format, since previously all had been square.

Sebastián I's decree regarding the flag also determined that the number of castles on the border of the flag should be definitively established at seven, as Juan II had already ordered.

1580 to 1640

During the period in which Portugal was under the rule of the House of Austria (1580 - 1640), along with the rest of "las Españas", or Spain (name given to the group of kingdoms peninsular, both by Iberians and by foreigners), in which each kingdom, and more specifically the Kingdom of Portugal remained separate from the other domains of the House of Austria, kept the arms and the flag. This fact took place at the beginning of the dynastic union, in which all the kingdoms of the Iberian Peninsula remained under the same king.

Where there was a change was in the arms of the House of Austria that reigned in Spain, with the superimposition of the Portuguese coat of arms on the whole Castilla-León-Granada/Aragón-Sicily). This position of the Portuguese shield in the armorial complex of the domains of the Spanish Crown was one of the most debated points between Cardinal Enrique I and Felipe II (through their plenipotentiary ministers Cristóbal de Moura and the Duke of Osuna). From the moment the Portuguese king understood that it would be impossible to resist the Castilian pressure for the absorption of Portugal, the old cardinal asked the Spanish monarch that the Portuguese coat of arms occupy one of the most important places in his new arms.. Philip's ambassadors rejected this proposal, considering that His Catholic Majesty could not "do such notable harm to the oldest domains of his monarchy" (Castile and Aragon), but that, nevertheless, he would give the arms of Portugal the place of the most honorable piece of the shield. Being so, he would end up placing them in a point worthy of the shield.

Note that this banner, however, was not the flag of a country or state. It represents, yes, the power of a royal family over its various European domains. Its use in Portugal was little minority, having been used only on the occasion of the visits of Felipe II to Tomar and Felipe III to Lisbon in 1619. There are still some copies of the flag on some artillery pieces that are preserved in the Military Museum of Lisbon and in the Museu da Marinha.

On the other hand, the flag of the Tercios (the red cross in the shape of an X of Burgundy) became co-official, along with the Portuguese maritime flag.

Sometimes, in certain representations (of unknown origin) the flag adopted by Sebastian I appears surrounded by 16 olive branches (with 10 visible bouquets and another 6 hidden), giving a particular enhancement to the Portuguese coat of arms. Thus, if the conservation of arms and the national flag seems to demonstrate the respect of the Hispanic monarchs for the customs and independence of Portugal, as agreed in the Courts of Tomar, in the same way that the individual royal banners of other kingdoms of the Crown. The presence of plant elements could represent the following theories:

- The joy shown by the new king in obtaining the dominion of Portugal (or the other way around, the joy of the Portuguese ruling classes, enchanted with a union that provided for charity, especially at the economic level);

- the relative peace with which the fusion of the crown of Portugal was made to the domains of the Austrias or the desire of the new king that peace should reign again in Portugal;

- be a symbol of the victory of Castile, thus demonstrating the conquest and submission of Portugal. This interpretation seems unconsistent, taking into account the effort made by Philip II to pacify the country and not to hurt his pride;

- Finally, when Felipe II entered Elvas, in order to meet the Cortes de Tomar and thus be a king jury in the month of December 1580, precisely when the peasants celebrate the harvest of the olives, there is also one who suggests that the new monarch decided to add to the Portuguese flag that plant element in memory of that trip, or that they were the branches of olive an invitation to the Portuguese people to promote the agriculture.

It seems that the flag was adopted in 1616.

1640 to 1667

With the restoration of independence, that is, with the end of the Philippine dynasty, the flag remained unchanged except for a small aesthetic detail: it returned to the round Portuguese shield. In essence, this was the base of the flag used by Portugal until Liberalism. During this period, the flag of the restoration was also used, which was the flag of the Order of Christ with a green background.

Meanwhile, King John IV by decree of March 25, 1646 declared Nuestra Señora de la Concepción patron of the kingdom and adopted, as his personal flag, the national flag with a blue background.

1667 to 1707

In this year the coup d'état took place that took power from Alfonso VI and placed his brother Pedro II in the regency of the kingdom, who proceeded to a new change in the flag (for the same reasons as Alfonso III, Juan I and Manuel I). The royal crown closed with three diadems now has five visible diadems, thus symbolizing a new reinforcement of royal authority, although it also conformed to the aesthetic standards of the time.

D. Pedro used the national arms on a green background as his personal flag.

1707 to 1816

With the accession to the throne of Juan V, the changes in the flag are merely aesthetic, hardly attending to the taste of the Baroque era. The lower border ends in a counter-curve, in the French tradition, and the purple bonnet is added to the royal crown. Note the symbolic importance that the purple color had at the time, since it was the imperial color par excellence. This change was not unrelated to the discovery of gold in Brazil, which made it possible to finance many of the works of that reign, including the attribution by the Pope of the dignity of Patriarchate to the city of Lisbon (1716) and the granting of the title His Most Faithful Majesty to King John V and his successors (1744).

John V himself used the national arms set on a crimson flag as his personal banner. As the end of the XVIII century approaches, the external decoration of the shield becomes more intricate and complex, according to the artistic patterns of the time, influenced by the Rococo.

1816 to 1826

By decree of the Prince Regent Don Juan, signed on December 16, 1815, Brazil was elevated to the status of Kingdom within the Portuguese State, which came to have the official name of United Kingdom of Portugal, Brazil and Algarves. Thus, a new alteration in the national arms was carried out, sanctioned by letter of law of Juan VI of Portugal on March 13, 1816. To represent Brazil within the framework of the new kingdom, an armillary sphere of gold in field of azur, surmounting the set a closed royal crown (in the same way that, legendarily, the quinas represented the kingdom of Portugal and the gules border with castles the kingdom of the Algarves).

Thus, an old symbol associated with Manueline imperial imagery was recovered to represent the new kingdom. Brazil itself had the right to have its own flag, which was similar to the Portuguese one, except for the absence of the Portuguese coat of arms — that is, it was limited only to a golden armillary sphere seated on a blue flag. The rest was a variation of the flag already used by the heir to the crown as Prince of Brazil.

The national arms, which consisted of the Portuguese coat of arms wrapped by the necklace of the Order of Christ and by two griffins, came to have three griffins, symbolizing the new kingdom of Brazil integrated into the Portuguese Crown.

1826 to 1830-1834

Having been officially recognized the independence of Brazil in 1825 by Portugal (through the Treaty of Rio de Janeiro), after the death of King John VI, in March 1826, it returned to the old design of the flag that had been adopted by Juan V in 1707. The reason for the change was that it did not make sense to maintain in the national arms a symbol that represented a now independent country.

This flag was abandoned in 1830 by Queen María II and absolutism until its defeat and capitulation in Évora Monte four years later.

1830 to 1910

The last monarchical flag came into force by decree of October 18, 1830, issued by the Council of Regency on behalf of Queen Maria II of Portugal, that council that was in exile on Terceira Island (Azores), for cause of the Liberal Wars.

This determined that the national flag would become vertically divided into white and blue, leaving the blue on the side of the mast; On the set, in the center, the national arms should be based, each half on each color.

Tradition has it that the first constitutionalist flag would have been embroidered by Queen María II of Portugal herself and brought to the continent by the Bravos do Mindelo, when they disembarked near Vila do Conde to conquer Porto, where they would remain besieged for just over a year.

There has been some controversy about the proportions of white and blue in this flag. The flag for terrestrial use was also divided into white and blue; the one for naval use, that yes, presented blue and white in the proportion of 1:2, somewhat similar to what happens with the current Portuguese national banner.

Since 1910

After the republican revolution, on October 5, 1910, the traditional flag of the constitutional monarchy (blue and white) was abolished and the State promoted a flag contest to represent the new government.

There was then a great debate to decide whether to keep the blue and white of the monarchy or to adopt the green and red of the Portuguese Republican Party. Although many of the proposals for the new flag focused on blue and white (such as that of the poet Guerra Junqueiro, among others), the winner was a red and green flag, colors associated with the PRP since the failed revolt of January 31, 1891. The authors of the current design of the national symbol were Columbano Bordalo Pinheiro, João Chagas and Abel Botelho.

To choose the new flag, the government did not wait to obtain the approval of the Constituent Assembly nor proceeded to hold a plebiscite, as had been requested by those who were against the new colors of the flag.

Officially announced on June 30, 1911, it was based on the flag used by Machado Santos, the "hero" of the Rotunda, as well as the one that hung from the rebel ship Adamastor during the revolt who brought the republic to Portugal. The government ordered that the new national symbol be made on a large scale and that flags be hung all over the country during the celebrations of December 1, Independence Day, which that year was renamed Dia da Bandeira.

Although there were two subsequent regime changes, successive Republican governments never altered the design of the flag.

Discordant minorities

Although today the "Verde y Rubra" is deeply rooted in the Portuguese people, it is rejected by those who disagree with the imposition without consultation on the people of colors historically alien to national identity, regardless of the regime of head of state in which the country lives, monarchy or republic. Monarchists, for example, continue to use the traditional blue and white liberal flag of 1830, and nationalists prefer to use the blue and white without the crown, as a republican flag.

Protocol

The constitutional regulation on the use of the national ensign is fragmentary and incomplete. In some cases, rules from the early 20th century still apply. However, in other regulations, such as military and naval, the regulations are more recent and complete.

A revision of decree number 150, published on March 30, 1987, establishes that the flag must be hoisted from 9 in the morning until sunset (during the night, it must be suitably illuminated), on Sundays and national festivities, throughout the national territory. It can be flown on days when there are official ceremonies or other solemn acts, and must be hoisted in loco. If the central government, the civil governor, the municipality or the heads of private institutions consider it appropriate, the flag can also be flown on any other date. However, it is a fundamental requirement that the official design be maintained and that the pavilion be kept in good condition.

In the headquarters of State institutions, the flag is allowed to fly every day. It can be hoisted in national civil and military monuments, or in other public buildings associated with the central, regional or local administration, as well as in the headquarters of public corporations and associations. Citizens and private institutions can make use of the national flag as long as existing legal procedures are respected. In the specific case of international organizations and interstate summits, the legal regime applicable to the flag will be the one established by the existing protocol rules for those specific cases.

If official mourning is declared, the flag must fly at half mast during the days set; the same will apply to the flags that fly next to the national ensign during mourning.

If the flag is displayed together with other banners, the national flag cannot be smaller, and must be located in a prominent place, in accordance with the protocol.

- Two masts — in the right mast, from the perspective of someone who observes it

- Three masts — in the central mast

- More than three masts:

- Inside a building — if they are odd, in the center, if they are pairs, to the right of the central point

- Outside a building — on the mast more on the right.

If the flagpoles are at different heights, the flag should occupy the highest point. The poles must be placed in decent places, both on the ground and on the facades and roofs. In public ceremonies in which the flag is not flown, it may be hung as long as it is not used to decorate or cover anything or for any other purpose that diminishes its dignity.

Other flags used in Portugal

Distinctive flags of State entities

Contenido relacionado

Flag of the savior

Hijra

Maus