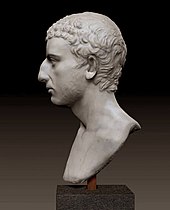

Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate —also known in Spanish as Poncio Pilatos— was a member of the equestrian order and fifth prefect of the Roman province of Judea, between the years 26 and 36. The canonical gospels present him as the executive responsible for the torture and crucifixion of Jesus of Nazareth, this being one of the few episodes in which he is mentioned, also known by Jewish authors (Philo, Flavio Josephus), Romans (Tacitus) and an epigraphic archaeological testimony.

Name

In Spanish its cognomen is usually Pilatos, perhaps due to the influence of the Greek form, Πειλᾶτος, or also reflecting the Latin nominative Pilatus. Even though Pilate can be considered the most correct form, Pilatos has been sanctioned for its use and, therefore, it is recognized by the Language Academies, which use it in various entries in the Dictionary of the Spanish language.

Biographical Fragments

The details of Pontius Pilate's biography before and after his appointment as prefect of Judea and after his participation in the trial against Jesus of Nazareth are unknown. Although several later textual sources (the Annales of Tacitus and the writings of Flavius Josephus) mention him as procurator (procurator) or as præses (governor), his official name was of praefectus which, as O. Hirschfeld had already suspected in 1905, was the one that corresponded to such a position until the time of Claudius. This data was undoubtedly documented after the discovery in 1961, among the remains of the Caesarea theater, an important old port between Tel-Aviv and Haifa, of an official fragmentary inscription, in which Pilate dedicated or remade a Tiberieum or temple of worship to the emperor Tiberius. The text of it is usually restored as follows:

- [-c. 3 -]s Tiberieum /

- [ -c.3- Po]ntius Pilatus /

- [praef]ectus Iudae[a]e /

- [ref]e[cit].

Another possible reference to Pilate occurs in an inscription on a thin sealing ring, discovered in 2018 in the city of Herodium. The inscription reads ΠΙΛΑΤΟ (Υ) (Pilato(u)), meaning "of Pilate". The name Pilate is rare, so the ring could be associated with Pontius Pilate; however, given the cheap material, it is unlikely that he would have had it. One possibility is that the ring belonged to someone who worked for Pilate, although it is also possible that the ring belonged to another individual with the same name.

Many details that lack any confirmation by other means, especially regarding his alleged repentance, suicide or conviction and beheading, have been added to the biographical tradition from the Acts of Pilate, a story contained in the apocryphal gospels, which circulated more profusely in the East; among those there is also a name for his wife, Claudia Prócula, canonized as a saint by the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and by the Byzantine Church, or an (improbable) birth of Pilate in Tarraco (Tarragona). The truth, however, is that historically nothing certain is known about the places of birth and death of Pilate, since the historical trace of him is lost in the years 36-37 when he, dismissed from office, he returned to Rome.

He was appointed prefect of Judea by Tiberius, at the request of his praetorian prefect, Sejanus, an adversary of Agrippina and a prominent anti-Jew.

He attempted to introduce images of the emperor into Jerusalem and build an aqueduct with funds from the Temple. Some authors point out that these disagreements with the Jewish people led him to transfer his command center from Caesarea to Jerusalem in order to better control the revolts, especially since armed groups opposed to Roman power began to operate in the province. It is assumed that the character mentioned in the gospels, Barabbas, was part of one of these gangs.

Pontius Pilate was relieved of command of Judea in AD 36, after heavily suppressing a revolt by the Samaritans, during which he crucified several rioters.

Pontius Pilate, historical figure

There are several historical references to Pontius Pilate. The oldest correspond to the Jewish philosopher Philo of Alexandria.

This author, who lived in the I century and acted as representative of his community before the imperial authorities, narrates a act of Pilate during his rule in Judea. On that occasion the conflict related to some gold shields bearing the names of Pilate and Tiberius, which the prefect had placed in his residence in Jerusalem. The Jews appealed to the Emperor of Rome, since under existing treaties Jewish law had to be respected in the city, and Pilate was ordered to bring the shields to Caesarea. Philo refers to Pontius Pilate as a man "of character inflexible and hard, without any consideration. Furthermore, according to this writer from Alexandria, the government of Pontius was characterized by "corruptibility, robbery, violence, offenses, brutality, continuous sentences without prior trial, and limitless cruelty."

Chronologically, the following mentions of Pilate in historical sources correspond to the works of Flavius Josephus, a Jewish historian and Roman citizen, who wrote in the last quarter of the century I. Indeed, both in the Jewish War, published between 75 and 79, and in Jewish Antiquities, from the 1990s, he appears several times as governor of Judea between the years 26 and 36. According to this historian, Pilate had a bad start in terms of relations with the Jews of his province: at night he sent Roman soldiers to Jerusalem carrying military banners with images of the emperor. And the situation was complicated because the insignia were placed in the Antonia Tower, the headquarters of the Roman cohorts, that is, right in front of one of the corners of the Temple complex, with the addition that the Jews believed that the Roman auxiliaries burned incense in front of the images of Tiberius and Augustus. This event caused great resentment because it violated the Torah's prohibition on the use of idols, and a delegation of leading Jews, representatives of the Sanhedrin, traveled to Caesarea to protest the presence of the regalia and demand that they be removed.

After five days of discussion, Pilate tried to intimidate those who made the request, threatening that his soldiers would execute them, but the bitter refusal of those to bow down, because they even bowed to the ground and showed their necks to be slit, although Pilate had only tried to trick them into giving in, and, given the high political cost, since Pilate had barely been in office for six weeks and would have had to execute up to six thousand Jews on that single occasion, he made him agree to his demand.

Josephus also mentions another uproar: at the expense of the Jerusalem temple treasury, Pilate built an aqueduct to bring water to Jerusalem from a distance of nearly 25 miles. Pilate asked the Grand Sanhedrin for funds from the Temple Treasury to finance the work, under the warning that if they were denied he would have to raise taxes. The priests initially refused, claiming that it was sacred money, but they gave in on the condition that the origin of the funds be hidden and that the main flow of the liquid reach the deposits of the Temple itself, but the agreement was discovered. Large crowds vociferated against this act when Pilate visited the city and the prefect sent disguised soldiers to blend into the crowd and attack it on signal, resulting in many Jews being killed or wounded.

Josephus reports that Pilate's subsequent dismissal was the result of complaints the Samaritans made to Vitellius, then governor of Syria and Pilate's immediate superior. The complaint concerned the Pilate-ordered killing of several Samaritans who were tricked by an impostor into gathering them on Mount Gerizim in the hope of discovering the sacred treasures that Moses had supposedly hidden there. Vitellius sent Pilate to Rome to appear before Tiberius, and put Marcellus in his place. Tiberius died in the year 37, while Pilate was still on his way to Rome, fearful of being tried and executed for his former relationship with Sejanus since, after his fall, all who were associated with him were treated as enemies by Emperor Tiberius and mostly executed. It has even been linked to his decision to give in to pressure from the Jewish Sanhedrin at the trial of Jesus — when the priests reminded him that if he released an alleged subversive like Jesus, who claimed to be king, then he was not a friend of Caesar, it is that is, of the emperor of that moment, Tiberius—with the intent to save his career and even his life and thus prevent Tiberius from suspecting his loyalty and sending him to Rome to investigate and try him as an associate of Sejanus. In addition, and since Sejanus had harassed the Jewish colony in Rome during his lifetime, after his death Tiberius ordered Pilate to change towards a policy favorable to Jewish customs.

The Roman historian Tacitus, born around the year 55, who was not a friend of Christianity and wrote shortly after the year 100, mentions Pilate in connection with the Neroian persecution and the origin of the Christians: «Christ, the founder of the name, had suffered the death penalty in the reign of Tiberius, sentenced by the procurator Pontius Pilate, and the pernicious superstition (Christianity) stopped momentarily, but it arose again, not only in Judea, where that plague began, but in the capital itself (Rome)...".

The Christian apologist and philosopher Justin Martyr, who wrote in the middle of the second century, points out regarding the death of Jesus: «By the Acts of Pontius Pilate you can determine that these things happened». A text that has been controversial because it supposes the existence of legal testimony on the trial of Jesus of Nazareth. He adds that these same records mentioned the miracles of Jesus, of which he says: "From the Acts of Pontius Pilate you can learn that He did those things." According to some authors, these official records, which are not preserved, could still exist in the second century, for which Justin urged his readers to check with them the veracity of what he said. Similarly, in his Apologeticus, written in 197, Tertullian reported original data on Pilate according to which the governor would have made a report to the emperor on events in Judea in relation to Christ. This report is also mentioned by Jerónimo de Estridón in his Chronicon (c. 380), and in the Pascual Chronicle, although it is not It is not known if they took the information from an independent source or relied on Justin's news. The Acts of Pilate that are currently preserved are an apocryphal work that does not seem to be related to the one mentioned by Justin and, certainly, are much later.

Pontius Pilate in the Gospels

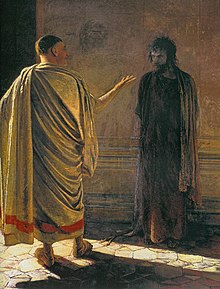

According to the Synoptic Gospels, Jesus was seized by a group of armed men belonging to the Temple guard, by order of Caiaphas and the high priests. Instead, the Gospel of John states that he was captured by a Roman company under the command of a tribune, which would suggest that it was by order of the prefect. The gospels say that, after a nightly interrogation, the Sadducee leaders brought Jesus before the Roman prefect early in the morning, since the Romans only held trials before noon, requesting Pilate to execute him, since they had found him guilty. of blasphemy, but capital punishment could only be applied by the Romans. Pilate sends Jesus to Herod Antipas due to a conflict with the jurisdiction corresponding to a prisoner from Galilee. Upon being returned to his hands, Pilate declares himself incompetent to resolve religious matters and declares not to find him guilty. The Jewish leaders then change the charge against Jesus to sedition. Despite not finding him guilty, Pilate —knowing that it was Easter Eve— lets the people decide between releasing a prisoner named Barabbas or freeing Jesus.

The people, led by the high priests, choose the release of Barabbas and the crucifixion of Jesus. Faced with this decision, Pilate symbolically washed his hands to indicate that he did not want to be part of the decision made by the crowd. Pilate says "I am not responsible for this man's blood." To which the crowd responds: "May his blood fall on us and on our descendants." Pilate is also reported to order the scourging of Jesus prior to his execution, but the gospels disagree as to whether this measure was taken as an attempted substitution of execution, or simply part of the execution process.

As for the apocryphal Gospels, there is a very brief and late Gospel of the death of Pontius Pilate and a much more important Gospel of Nicodemus, also called Acts of Pilate (Acta Pilati).

Pontius Pilate as symbol

According to Pérez-Rioja, "Pilato has become a traditional symbol of vileness and submission to the low interests of politics."

The act of "washing one's hands" carried out by Pilate in the Gospel of Matthew, along with other emblematic symbolic themes of the passion of Christ (the thirty silver coins, the kiss of Judas, the rooster's crow), left your brand in everyday language and images.

Then Pilate, seeing that nothing advanced, but rather tumult was promoted, took water and washed his hands before the people, saying, "I am of the blood of this righteous man. You will see."Gospel of Matthew 27: 24

According to J. L. McKenzie, the act of "washing your hands" was no longer part of the legal process: there was no longer a hearing or questioning of witnesses, but rather a way of making the crowd communicate, through a Jewish custom, his detachment from the case. The sentence was implicit. The important factor was no longer the process, but the pressures that caused the result of the process. The gospels clearly imply that Pilate realized that there was no authentic charge against Jesus, and the symbolic washing of hands added by Matthew underscores this. This act remained in the culture as a symbol of those who, for personal convenience, give in to the pressure of others while trying to ignore an unfair verdict. The washing of hands implies an act of purification empty of content that cannot conscientiously evade responsibility, since whoever condemns an innocent man for pressure is not morally far above those who exercise it.

Pontius Pilate in art

Aesthetically, Pontius Pilate has caught the attention and imagination of writers (his person became an almost obligatory character in any representation of the passion of Jesus Christ), plastic artists, and film producers and directors.

Pontius Pilate in literature

Pontius Pilate is the main character of «The Procurator of Judea», by Anatole France, published in Le Temps on December 25, 1891, and later included in the collection of short stories The mother-of-pearl case (1892). Subsequently, the story was published separately in bibliophile editions, the first of which was in 1902 with illustrations by Eugène Grasset. In this story, Pontius Pilate, already retired in Sicily, meets Elio Lamia, an acquaintance from his period as procurator of Judea. In two successive conversations they review the events they experienced together. Both expose a radically opposed vision of history and the Jews. The story anticipates by more than a decade the denunciation of anti-Semitism that will manifest itself in French society as a result of the Dreyfus case.

In 1980, Leonardo Sciascia translated "The Procurator of Judea" into Italian, as he considered it one of the most perfect of its kind. It served as Joyce's inspiration for Dubliners, especially for the best-known story, "The Dead". It is also worth noting the allusion to his name in the character "Poncia" in the drama The House of Bernarda Alba, by Federico García Lorca.

Pontius Pilate is portrayed in Mikhail Bulgakov's The Master and Margarita as ruthless and yet complex and humane. The novel describes his encounter with Jesus the Nazarene, showing his recognition of an affinity and spiritual need for him, and his reluctant surrender, though resigned and passive, to those who wanted to kill him. Here Pilate exemplifies the statement "Cowardice is the worst of vices", and therefore serves as a model, in an allegorical interpretation of the work, for all people who have "washed their hands" in silence or taken active part in the crimes committed by Joseph Stalin.

Pontius Pilate in the cinema

In the cinematography, various actors played the role of Pontius Pilate.

| Year | Movie | Director | Actor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2019 | Jesus of Nazareth | Rafael Lara | Sérgio Marone |

| 2018 | Mary Magdalene | Rodrigo Lalinde | Lucho Velasco |

| 2018 | Jesus | Edgard Miranda | Nicola Siri |

| 2016 | Ben-Hur | Timur Bekmambetov | Pilou Asbæk |

| 2016 | Risen | Kevin Reynolds | Peter Firth |

| 2007 | In search of the tomb of Christ | Giulio Base | Hristo Shopov |

| 2004 | The Passion of Christ | Mel Gibson | Hristo Shopov |

| 2001 | Gli amici di Gesú - Tommaso | Rafaelle Mertes | Mathieu Carrière |

| 2001 | Gli amici di Gesú - Giuda | Rafaelle Mertes | Mathieu Carrière |

| 1999 | Mary, mother of Jesus | Kevin Connor | Robert Addie |

| 1999 | The Bible: Jesus | Roger Young | Gary Oldman |

| 1988 | The Last Temptation of Christ | Martin Scorsese | David Bowie |

| 1987 | According to Pontius Pilate | Luigi Magni | Nino Manfredi |

| 1985 | A.D. Anno Domini | Stuart Cooper | Anthony Zerbe |

| 1980 | The Life of Our Lord Jesus Christ | Miguel Zacarías | Tito Novaro |

| 1980 | The day Christ died | James Cellan Jones | Keith Michell |

| 1980 | The Public Life of Jesus | John Krish | Peter Frye |

| 1979 | Brian's life | Terry Jones | Michael Palin |

| 1977 | Jesus of Nazareth | Franco Zeffirelli | Rod Steiger |

| 1973 | Jesus Christ Superstar | Norman Jewison | Barry Dennen |

| 1970 | Jesus Our Lord | Miguel Zacarías | Tito Novaro |

| 1965 | The Process of Christ | July Bracho | Julian Soler |

| 1965 | The greatest story ever told | George Stevens | Telly Savalas |

| 1962 | Pontius Pilate | Irving Rapper | Jean Marais |

| 1961 | Barrabás | Richard Fleischer | Arthur Kennedy |

| 1961 | King of Kings | Nicholas Ray | Hurd Hatfield |

| 1959 | Ben-Hur | William Wyler | Frank Thring |

| 1952 | The martyr of Calvary | Miguel Morayta Martínez | José Baviera |

| 1945 | Mary Magdala, sinner of Magdala | Miguel Contreras Torres | José Baviera |

| 1945 | Queen of Queens: The Virgin Mary | Miguel Contreras Torres | José Baviera |

| 1942 | Jesus of Nazareth | José Díaz Morales | José Baviera |

| 1927 | King of kings | Cecil B. DeMille | Victor Varconi |

| 1912 | From the manger to the cross | Sidney Olcott | Samuel Morgan |

Contenido relacionado

Ligurians

My belarusy

Boabdil