Polytheism

Polytheism is a cup of religious or philosophical conception based on the existence of various divine beings or gods. In most religious religions that accept polytheism, the different gods are representations of forces of nature or ancestral principles, and can be seen as autonomous or as aspects or emanations of a creator deity or transcendental absolute principle (monistic theologies), which it manifests itself immanently in nature (pantheistic and panentheistic theologies). Many polytheistic deities, with the exception of Egyptian or Hindu deities, are conceived on a corporeal rather than an ethereal plane.

Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism—the belief in a singular God, in most cases transcendent. Polytheists do not always worship all gods equally, as they may be henotheists, who specialize in the worship of a particular deity. Other polytheists may be katenotheists, worshiping different deities at different times.

According to David Hume, polytheism was the first religion of human beings. It was indeed a typical form of religion during the Bronze Age and Iron Age up to the Axial Age and the development of the Abrahamic religions, the last of which espoused monotheism. It is well documented in the historical religions of classical antiquity, especially ancient Greek religion and ancient Roman religion, and after the decline of Greco-Roman polytheism in tribal religions such as Germanic paganism, Slavic paganism, and Baltic mythology.

Other historical examples are the ancient Egyptian, Greek, Roman, Celtic or Nordic religions, in the European and North African areas, as we must not forget the Amerindian religions, such as the Inca, the Mayan or the Mexica, to mention a few pre-Columbian.

But it should not be considered so much a belief of the past as of total present and actuality: the most important polytheistic religions existing today are Chinese traditional religion, Hinduism, Japanese Shintoism, Santeria and various neopagan religions.

Origin of the term

The word polytheism comes from the Greek poli 'many', and theos 'god'; that is, 'many gods'. It was the Jewish writer Philo of Alexandria who first used the term arguing with the Greeks. After the expansion of Christianity around the Mediterranean and on the part of Europe, the word pagan, gentile or the more pejorative of idolater began to be used more to refer to non-Christians. It would be Juan Bodino in the 16th century who would recover the term.

Aspects of polytheism

Polytheism is a type of theism. Within theism, it contrasts with monotheism, whose belief in a singular God, in most cases transcendent. Polytheists do not always worship all gods in the same way, as they may be henotheists, who specialize in the worship of a particular deity. Other polytheists may be katenotheists, who worship different deities at different times.

The system encompasses the personification of natural elements, feelings and human activities, usually organized in a hierarchy or pantheon. It is not about different nomenclatures for a single deity, but about different gods with clearly identifiable individual characteristics. In polytheism each deity can be honored and invoked individually, depending on the aspects that define it.

In polytheistic societies there is usually no theology as such, although it tends to coexist with quite complex philosophical and ethical systems. Each supernatural force or transcendental event (such as lightning, death or pregnancy) responds to established mechanisms, which make up a complex, highly hierarchical cosmic order, described through myths, legends and sacred works. In polytheism, due to a highly consolidated network of transmission, oral or written, knowledge is cumulative, that is, it is expanded by the speculation of the individuals dedicated to it (shamans, sorcerers, priests, poets), or by contact intercultural.

It is usually pointed out that polytheism often corresponds to equally hierarchical societies, with a strong stratification into social classes. Common examples would occur in Ancient Egypt, Mesopotamia, in classical Greek and Roman culture or in Hinduism. Some polytheistic beliefs also place the preeminence of a god over the rest of the pantheon (cult known as henotheism), which led anthropologists to believe that this would be the natural step towards monotheism.

Polytheism is considered by some anthropologists as the next step to animism, a more advanced form of religiosity (typical of a certain level of civilization), in which the forces of nature are discriminated, separated and selected, and, finally, represented by a series of anthropomorphic gods.

Polytheism in antiquity

Throughout history, some prominent examples of polytheism can be found in the Sumerian and Egyptian cultures, in the mythology of the Aesir and the Vanir –the two pantheons of Norse mythology, superior and minor respectively–, the Orishas of the Iorubes, the gods of the Aztecs and many others. Today most of the religions of the past are polytheistic and are interpreted in relation to mythology, even if the stories about the gods that these cultures have developed are part of cults and religious practices. The exceptions are few; These include the Abrahamic religion and possibly Atenism promulgated around 1350 BC by Akhenaten in Ancient Egypt.

In many civilizations, the pantheon of divinities tended to grow over time. The particular deities, which were originally worshiped in some specific places and areas, were integrated into the religious cult of other cities and territories after clashes between towns, periodic conflicts between two territorial powers. An example of this type of change can be observed in the evolution around the deities called genius loci, which were the local spirits.

Anthropomorphism is another very characteristic feature of polytheism and refers to emotions, motivations and behaviors that are similar to those of man. Thus, the gods of polytheism are often portrayed as complex characters of more or less status, with abilities, needs, desires, and histories in many ways similar to those present in human beings, but with additional individual powers, abilities, knowledge, and skills. or superhuman perception. It has been suggested that this phenomenon is at the origin of the divinization of certain forms of authority, such as the pharaohs of Ancient Egypt, the emperors of ancient Rome and China, to mention some of the great civilizations. Polytheism is independent of the cultural stage and is present both in the most primitive societies and in sophisticated civilizations such as Babylonian, Sumerian, Chinese, Mayan, Aztec, Inca, Greco-Roman or Egyptian civilizations, and is a conspicuous element of widespread religions such as Taoism, Shintoism or Hinduism.

Gods and deities

Radical polytheists believe that the gods are different and independent beings, but they may also believe in a unifying principle, as is the case with Platonists. Moderate polytheists respect the multiplicity of gods, but come to see it as a multiplicity of a higher divine unity, not a personal God as in monotheistic religions, but rather a multiple divine reality. In fact, this monism extends and in a certain way approaches monotheism, but without form and without the attributes that constitute it. The most characteristic example would be that of Braman, with Hindu currents such as Vedanta and Yoga, and represents a philosophical and spiritual concept that refers to the original principle of the Universe. Even some modern neopagan currents follow this model.

Polytheism cannot be neatly separated from the animistic beliefs that prevail in most popular religions. The gods of polytheism are, in many cases, the highest level of a continuum of supernatural beings or spirits, which may include ancestors, demons, specters, and other magical or mysterious beings. In some cases these spirits are divided into celestial or chthonic (of the Underworld), and the belief in the existence of all these beings does not imply that they are all worshiped equally.

Although many forms of Buddhism include the veneration of bodhisattva, they are not viewed as divine entities. On the contrary, bodhisattva are considered to be human beings who have achieved a higher level of enlightenment, and one of the principles of Buddhism is that, in the course of many lifetimes, any human being can reach that level of enlightenment. a similar level.

Just because a person can believe in several gods does not necessarily mean that all of them have to be worshipped. Many polytheists believe in the existence of more than one god, but only worship one or a few of them. Max Müller speaks of a cult tendency directed towards a being or principle, recognized as such, but which has many manifestations; this type of theism was called henotheism. Some people see henotheism as a form of monotheism, and others, as monism; Also some historians have claimed that monotheistic religions have originated from henotheism. From the perspective of current Christians, Jews and Muslims, however, henotheism is considered as an equivalent to polytheism and a conception away from their religious system.

Types of deities

Some types of deities often found in polytheism may include:

- Creative deity

- Cultural hero

- Deity of death (ctonic)

- Deity of life-death-revival

- Goddess of love

- Goddess mother

- Political deity (as a king or emperor)

- Deity of the sky (celestial)

- Solar deity

- Entabanous Deity

- Water deity

- Gods of music, arts, science, agriculture or other activities.

Differences between monotheism and polytheism

Faith, believing, is the basis of monotheism; beliefs and faith are concepts alien to polytheism. Polytheistic religions do not raise the problem of origins and creation; in most of them the world is eternal, or at least finds its origin in a primordial chaos, by the intervention or not of the gods.

Faced with the diversity and multiplicity of the world, certain forms of polytheism consider the multiplicity of creations and origins, which are produced by the transformation of the existent. Therefore, there is consequently no creation myth in pagan religions that the faithful have to accept dogmatically, although there may be a predominant story, such as the Theogony of Hesiod.

Each pagan religion has its own pantheon, which although relatively stable, admits some changes: it can develop and new gods can be incorporated, by importing other cults or by the birth of new local cults. Even so, if a new god is incorporated and has very similar characteristics to one that already exists, it is generally unified in a single figure that usually bears the name of the traditional deity.

The cult is based on the veneration of the gods, of which one or a small group stand out as more important, in order to assume the characteristics of the main deity. In the event that the worship of the less important gods disappears and only the veneration of a main god remains active, then one speaks of henotheism.

Mythology and religion

In classical times, Sallust (IV century AD) categorized mythology into five types:

- Theological

- Physics

- Psychological

- Material

- Mixed

Theological are these myths that do not use any visible form, but contemplate the very essence of the gods: for example, Chronos swallowed his children. Since divinity is intellectual, and everything becomes intellect in itself, this myth is expressed in the allegory of the essence of divinity.

Myths can be considered physically when they express the activity of the gods to the world.

The psychological way consists of considering (myths as allegories of) the activities of the soul itself and/or the acts of thought of the soul.

The material consists of considering material objects as if they were actually gods, for example: calling the ocean Nesga, Okeanos, or heat Typhoon on earth.

The mixed type of myth can be seen in many cases, for example, they say that at a banquet of the gods, Eris, the discord, threw down a golden apple proclaiming that only the most beautiful could have it and the goddesses fought by her, and so they were sent by Zeus to Paris to be judged by him. Paris saw Aphrodite as the most beautiful and gave her the apple. Here the banquet represents the hypercosmic powers of the gods, which is why they are all together. The golden apple is the world, which was formed from the opposites, and is naturally "launched by Eris" (or the discord). Different gods bestow different boons upon the world, and therefore they are called 'fighting for the apple'. And the soul that lives according to sense - for this is what Paris is - sees not the other powers of the world, but only beauty, declares that the apple belongs to Aphrodite.

Relation to idolatry

Polytheism is seen by many monotheists as a form of idolatry. Monotheists claim that all power comes from a single god and not from other entities or agents. Polytheists generally hold the conception that there is a supreme being or god who is above all other deities in their pantheon, but they do not consider it a single deity.

Since the monotheists of the Abrahamic religions believe in only one god, they generally consider it a sin to endorse polytheism or worship more deities that do not correspond to God, arguing that they are idolatrous acts or even demonic, sectarian or heretical.

The Biblical scribes of the Old Testament rejected the idolatry of Israel and considered other deities as mere idols without divinity or power. The early Christians, based on the teachings of Jesus of Nazareth that "there is only one God," rejected offerings to other deities.

Currently, both in Judaism, Christianity and their derived religions (Catholicism, Protestantism, Orthodoxism) and Islam, consider idolatry and sin any act that consists of believing or worshiping other deities, because they believe that God hates that they worship another god outside of him.

Despite rejecting polytheism or the veneration of other entities, some monotheistic religions, within their mythology, have a hierarchy of divine beings, such as angels, who are the "helpers" of God, or the demons, who are the "enemies" of God. This is not much different from the notion of a supreme god with a hierarchy of divine beings or helpers.

Historical polytheism

Some known historical polytheistic pantheons include the Sumerian Egyptian gods, and the classical pantheon which includes ancient Greek religion and Roman religion. Table-classical polytheistic religions include the Norse mythology of the Æsir and the Vanir, the Ioruba, the gods of Aztec mythology, and many others. Today, historical polytheistic religions are pejoratively referred to as 'mythology', although the cultural stories that tell of their gods have to be distinguished from their religious worship or practice. For example, deities depicted in the conflicts of mythology were still sometimes venerated on the same side of each other's temples, illustrating the distinction in the minds of devotees between myth and reality. Due to the great similarity and relationships between the ancient European religions, it is speculated, within comparative religion, that there was a Proto-Indo-European religion, from which the religions of the different Indo-European peoples derive, and that this religion was an essentially numenistic naturalistic religion.. An example of a religious notion of this common past is the concept of Dyeus, which is documented in several different religious systems.

As stated above, the pantheons of many civilizations tend to grow over time. Deities first worshiped as patrons of cities or places were collected together as empires spread over larger territories. Conquests could lead to the subordination of the pantheon of older culture to a newer one, as in the Greek case of the Titanomachy, and possibly also the case of the Æsir and Vanir to Norse myths. The cultural exchange could lead to the fact that "the same" deity was recognized in two places under different names, such as the Greeks, Etruscans and Romans, and also to the introduction of elements of a "foreign" in a local cult, like the god of Egypt Osiris, worshiped over time in ancient Greece.

Older belief systems held that the gods influenced human lives. However, the Greek philosopher Epicur held that the gods lived incorruptible, happy beings who do not bother themselves with the affairs of mortals, but can be perceived by the mind, especially during sleep. Epicur believed that the gods were material, likenesses to humans, and that they inhabit the empty spaces between the worlds.

Hellenistic religion can still be considered as polytheistic, but with strong monistic components, and monotheism will eventually emerge from Hellenistic traditions in Late Antiquity in the form of Neoplatonism and Christian theology.

Neolithic

- Religion Serer

From the Bronze Age to Classical Antiquity

- Religions of the Ancient Near East

- Religion of Ancient Egypt

- Ancient Semitic Religion

- Historical Vedic Religion

- Ancient Greek religion

- Ancient Roman religion

- Celtic polytheism

From Late Antiquity to the High Middle Ages

- Germanic Paganism

- Slavic paganism

- Baltic paganism

- Finnish paganism

Ancient Greece

The classical scheme to ancient Greece of the twelve Olympians (the Canonical Twelve of art and poetry) were: Zeus, Hera, Poseidon, Athena, Ares, Demeter, Apollo, Artemis, Hephaestus, Aphrodite, Hermes, and Hestia. Although it is suggested that Hestia resigned when Dionysus was invited to Olympus, this is a matter of controversy. Robert Grabas, in The Greek Myths cites two sources in which Hestia obviously did not give up her place, although it is suggested that she did. Hades was often excluded because he inhabited the Underworld. All the gods had a power. There was, but a great deal of fluidity as to who was numbered among them in antiquity. Different cities often worshiped the same deities, sometimes with epithets that distinguished them and specified their local nature.

Hellenic polytheism spread beyond mainland Greece, on the Ionian islands and coasts of Asia Minor, to Magna Graecia (Sicily and southern Italy), and through scattered Greek colonies to the western Mediterranean, such as Massalia (Marseille) or Ampurias (Emporion). The Greek religion influenced the cult and beliefs of the Etruscans to form part of the later Roman religion.

Folk religion

The animistic nature of popular beliefs is an anthropological cultural universal. The belief in ghosts and spirits living in nature and the practice of ancestor worship is universally present in world cultures and periodically reemerges in monotheistic or materialistic societies as "superstition," the belief in demons, tutelary saints, fairies or aliens.

The presence of a full polytheistic religion, with ritual worship carried out by a priestly caste, requires a higher level of organization and is not present in all cultures. In Eurasia, the Kalash are one of the few cases of polytheism that has managed to survive. Furthermore, a large number of polytheistic folk traditions are subsumed into Hinduism, even though Hinduism is doctrinally dominated by monistic or monotheistic theology (Bhakti, Advaita Vedanta). Historical polytheistic Vedic ritualism survives as a minor stream in Hinduism, known as Shrauta. Wider is popular Hinduism, with rituals dedicated to various local or regional deities.

Problems and texts of Western historical polytheism

The origin of polytheism in the West (Eurasia and the Middle East) is found in the very origin of humanity, with the first human communities of hunter-gatherers being of a polytheistic type and continuing with the first human civilizations of a sedentary type in Sumer, with complex stratifications and strongly related to nature, ancestors and patrimonial histories, as demonstrated by the different funerary and tribal archaeological findings.

As it has been said, since monotheism there has been an attempt to see the previous polytheistic religions as barbaric or, in the case of Christianity during the Middle Ages and Islam, until today, they are related to the worship of demons and idolatry, being severely punished, often with torture or execution. As the texts that have come down to us demonstrate, often from second sources, it is observed that the religions prior to the domination of the great Western monotheistic religions contained great spiritual complexity, as demonstrated in the Eleusinian mysteries, in the texts of Sallust, Aristotle, Plato, Herodotus or in the Gallic War, Julius Caesar, regarding the religion practiced by the ancient Celts. But what we are left with is mostly second-hand conjecture and theories, since in trying to bring to light the religions of our ancestors, specialists run into a series of serious problems:

- The first polytheistic religions followed an unwritten oral tradition. In some cases this spread to the middle age, as in the case of the religion practiced by the Baltic peoples, the last pagan peoples of Europe, conquered by a crusade to the meek of the Teutonic knights, but the religion of which lived in secret and under the penalty of death until very much entered the XVII.

- Many of the sources dealt with by former political religions were second-hand observers who spoke of them when they had already been displaced. It is the case of the Prosaic Edda, Snorri Sturluson, compiled in an already Christianized Iceland. Thus the texts that have come to us contain strong synchrotic elements and influenced by the dominant monotheistic religion.

- In some cases the monotheistic religions that displaced the previous polytheistic religions sought the systematic disappearance of their priests, texts (if any) and faithful, following practices of forced conversions or violent persecution. Thus, for example, the cultural genocide that the first Christian king of Norway, Olaf Tryggvason, named Olaf Y, who linked the Seiðr -practicants of the ancient Nordic religion- in the skerry -small rocks in front of the Norwegian coast- during the rising tide because they drowned slowly.

Because of this, very little of their original texts have been preserved. Some of the most important texts of Western polytheistic religions that have survived first hand to this day are:

- The golden foils and the Papiros of Derveni, fundamental texts of Orphism, running religious and mysterical school of the Greek religion.

- The texts of the Pyramids and the Book of the Dead of the Egyptian religion.

Religions of the contemporary world

Buddhism and Shinto

In Buddhism, there are higher beings commonly called (or designated) as gods, the Devas, but Buddhism, at its core (to the original Pali Canon), does not teach the concept of praying to and worshiping the Devas or any god.

However, in Buddhism, the main leader 'Buddha', who pioneered the path to enlightenment is not worshiped in meditation, but simply reflected upon the meditating. Statues or images of the Buddha (Buddharupas) are revered in front to reflect and contemplate the qualities that the particular position of this rupa represents. In Buddhism there is no creator and the Buddha rejected the idea that a permanent, fixed, personal and omniscient deity could exist, uniting it in the basic concept of impermanence (anicca).

Devas, in general, are beings who have had more positive karma in their past lives than humans. His life expectancy, but eventually ends. When their lives are over, they are reborn as devas or other higher beings. When negative karma accumulates, they are reborn as humans or any of the other lower beings. Human beings and other beings can also be reborn as a deva in their next rebirth, if enough positive karma is accumulated.

Buddhism flourished in different countries, and some of these countries had polytheistic folk religions. Buddhism easily syncretizes with other religions. Therefore, it has mixed with popular religions and arose in polytheistic variants as well as non-theistic variants. For example, in Japan, Buddhism, mixed with Shinto, which worships deities called kami, created a tradition that prays to the Shinto gods as a form of Buddha. Therefore, there may be elements of god worship in some forms of later Buddhism.

The concepts of Adi-Buddha and Dharmakaya are the closest to monotheism of any other form of Buddhism. All famous sages and Bodhisattvas are considered to be a reflection of it. Adi-Buddha is not called the creator, but the origin of all things, being a deity in an emanationist sense.

Christianity

Historically most Christian churches have taught that the nature of God is a mystery, in the original, technical sense, something that has to be revealed by special revelation rather than deduced -it through a special revelation. general. Among the early Christians there was considerable debate about the nature of God, with some factions advocating the deity of Jesus and others calling for an Arian conception of God.

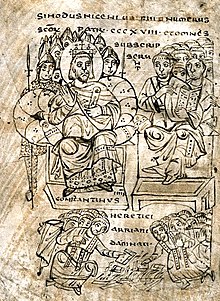

These issues of Christology will be one of the main issues of controversy at the First Council of Nicaea, held in Nicaea (in present-day Turkey), convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine I the Great in 325, it was the first (or second, if the Apostolic See Council of Jerusalem is counted) ecumenical, council of bishops of the Roman Empire, and resulted in the first uniform Christian doctrine, called the Nicene Creed. With the creation of the Creed, a precedent was set for later 'councils of (ecumenical) general bishops', (synods) to create statements of belief and canons of orthodox doctrine - the intent is to define unity of the beliefs of the State Church of the Roman Empire and to eradicate heresy.

The purpose of the Council is to resolve disagreements within the Church of Alexandria about the nature of Jesus in relation to the Father, in particular, whether Jesus was of the same substance as God the Father or simply of similar substance. Alexandre and Atanasi of Alexandria took the first position, the popular priest Arri, from whom the term Arianism comes, takes the second. The Council decided against the Arians overwhelmingly (of the roughly 250-318 attendees, all but 2 vote against Arri).

The orthodox Christian traditions (Orthodox, Catholic, Protestant and Evangelical) follow this decision, which was codified in 381 and achieved its full development through the work of the Cappadocian fathers. They consider God to be a triple entity, called the Trinity, comprising the three "persons" God the Father, God the Son, and God the Holy Spirit, the three are described as "of the same substance" (ὁμοούσιος). The true nature of an infinite God, however, is claimed to be beyond definition, and "the word" person "is nothing more than an imperfect expression of the idea, and it is not biblical. In common language it refers to an independent rational and moral individual, possessing self-awareness, and aware of his identity amidst all changes. Experience teaches that when you are a person, you also have a different individual essence. Each person is a different and separate individual, in which human nature is individualized. But in God there are no three individuals, alongside and independent of, only different personal characters within the divine essence, which is not only generically, but also numerically, one."

Some critics, especially among Jews and Muslims, argue that because of its adoption of a Trinitarian concept of deity, Christianity is actually a form of tritheism or polytheism, eg see shituf. This concept dates back to the teachings of the Church of Alexandria, which asserted that Jesus, having appeared later in the Bible than his 'father', had to be a lesser secondary God, and therefore "different". This controversy brought the convention of the Council of Nicaea in 325 Wed. Mostly Christians affirm that monotheism is fundamental to the Christian faith, as the Nicene Creed (and others), which gives the orthodox Christian definition of the Trinity, begins like this: "I believe in one sun God".

Some Christians refuse to incorporate Trinitarian theology, such as Jehovah's Witnesses, Mormons, Unitarians, Christadelphians, the General Conference Church of God, Socinism, and some elements of Anabaptism do not teach the doctrine of Trinitarianism at all. the Trinity. In addition, Oneness Pentecostalism rejects the creedal formulation of the Trinity, that there are three different and eternal persons in one being, instead believing that there is one sun God, a singular spirit that manifests itself in many different forms, including the Father. and the Son and the Holy Spirit.

Deism is a philosophy of religion, which arose from the Christian tradition during the Modern Age. It is postulated that there is a God who, however, does not intervene in human affairs. Alvin J. Schmidt argues that since the 1700s, expressions of Civil Religion in the United States have shifted from deism to a polytheistic stance.

Unitarianism is a Christological doctrine in contrast to Trinitarian Christianity, postulating that Jesus was fully human, a Messiah.

Hinduism

Hinduism is far from being a monolithic religion: many and varied religious traditions and practices are grouped under its umbrella term, and some modern scholars have questioned the legitimacy of this artificial unification, suggesting that one should speak of "Hinduisms" in the plural. Theistic Hinduism encompasses both monotheistic and polytheistic tendencies and variations or mixtures of both structures. The Hinduism Facts website states that there is a Supreme Being (Braman) and a series of deities. These deities are known as "semidéus" and erroneously as "gods".

Hindus worship God in the form of the Murti, an icon. Murti Puja (worship) is like a way of communicating with the formless, abstract divinity (Braman in Hinduism), who creates, sustains and dissolves creation.

Some Hindu philosophers and theologians hold to a transcendent metaphysical structure with a single divine essence. This divine essence is generally referred to as Braman or Atman, but understanding the nature of this absolute divine essence is the defining line of many Hindu philosophical traditions such as Vedanta.

Among secular Hindus, some cross over into different deities emanating from Brahman, while others practice more traditional polytheism and henotheism, focusing their worship on one or more personal deities, while making a concession to the existence of the other deities. others.

Academically speaking, the ancient Vedic scriptures, upon which Hinduism is derived, describe four authoritative lines of disciplinary teaching that trace their origins back thousands of years. (Padma Purana). Four of them propose that the Absolute Truth is totally personal, as in Judeo-Christian theology. Because Primal Original God is personal, both transcendent and immanent to all creation. It can be, and often is, approached through the worship of the Murti, referred to as 'Archa-Vigraha', which are described in the Vedas as portraying the various forms and spiritual dynamics of him. This is Vaisnava theology.

The fifth disciplic line of Vedic spirituality, founded by Shankaracharya, promotes the concept that the Absolute is Braman, without clear differentiations, without will, without thought, without intelligence.

In Hinduism's Smarta denomination, the philosophy of Advaita exposed by Adi Shankara allows the veneration of numerous deities, understanding that all of them are nothing more than manifestations of an impersonal divine force, Braman. Therefore, according to various schools of Vedanta like that of Shankara, which is the most influential and important within the tradition of Hindu theology, there are a large number of gods in Hinduism, for example, Vishnu, Chiva, Ganesha., Hanuman, Lakshmi and Kali, but they are essentially different forms of the same 'being'. However, many Vedanta philosophers also argue that all people are united by the same impersonal and divine power in the form of the Atman.

Many other Hindus, however, saw polytheism as much better than monotheism. Ramo Swarup, for example, notes the Vedas as specifically polytheistic, and asserts that, "only one form of polytheism can do justice to this variety and richness alone." Sita Ram Goel, another historian Hindu of the 20th century, wrote:

"I had the opportunity to read the manuscript of a book that [Ram Swarup] had just written in 1973. It was a profound study of monotheistic religion, the central dogma of Islam and Christianity, as well as a powerful presentation of which monotheists denounce as Hindu polytheism. I've never read anything like that. It was a revelation to me that monotheism was not a religious concept, but an imperialist idea. I have to confess that I myself had leaned towards monotheism until now. And I had never thought that a multiplicity of gods was the natural and spontaneous expression of an evolved consciousness. "

This notion of polytheism, however, is always understood in the sense of polymorphism - one God of many forms and names. The Rig Veda, the main Hindu scripture, makes it clear as follows:

They call it Indra, Mitra, Varuna, Agni, and he is the heavenly Garutman of noble wings. The one who is oneThe sages are given many titles by calling it Agni, Yama, Matarisvan. Book I, Hymn 164, verse 46 Rigveda

Serer Religion

In Africa, the polytheism of the Serer religion dates back as far as the Neolithic (possibly earlier) when the ancient ancestors of the Serer represented their Pangool to the Tassili Ajjer the supreme creator deity in the Serer religion is Roog. However, there are many deities and Pangool (singular: Fangool, intercessors with the divine.) in the Serer religion, each serving their own purpose and serving as Roog's agent on Earth. Among the Cangin speakers, a subgroup of the Serer, Roog is known as Koox.

Neopaganism

Hard polytheism holds the belief that the gods are different from each other, separate, real divine beings and not psychological archetypes or personifications of natural forces. Thus, they reject the idea that "all gods are one god." and they do not necessarily consider the gods of all cultures to be equally real, a theological position known formally as integrative polytheism or omnitheism.

This is in contrast to soft polytheism, which holds that the gods are aspects of a single god, psychological archetypes, or personifications of natural forces.Soft polytheism is frequent in the New Age and a leap forward from syncretic neopaganism, such as interpretations of deities as archetypes of the human psyche. The occultist Dion Fortune was one of the main popularizers of soft polytheism. In his novel, The Sea Priestess he wrote, "All gods are one sun God, and all goddesses are one goddess, and there is one initiator." This sentence is very popular with some Neopagans (particularly Wiccans) and often incorrectly believed to be just a work of modern fiction. However, Fortune did, in fact, cite an ancient source, the novel The Golden Ass by Lucius Apuleius. Fortune's soft polytheism straddling monotheism and polytheism has been described as "pantheism" (Greek: πάν pan 'everything' i θεός theos 'god'). Notwithstanding the "pantheism" It has a long history of use to refer to an immanent divinity that is all-encompassing.

Wicca

Wicca is a duotheistic faith created by Gerald Gardner, within which polytheism is permitted. Wiccans specifically worship the Lord and Lady of the Isles (their names are sacred under oath) It is an orthopractical mystery religion that requires initiation into the priesthood to consider oneself a Wiccan. Wicca emphasizes duality and the cycle of nature.

Reconstructionism

Reconstructionists are neopagans who apply academic disciplines such as history, etymology, archaeology, linguistics, and others to a traditional religion that has been destroyed, such as Norse paganism, neo-Hellenism, Celtic paganism, and others. After investigating his career, a reconstructionist applies the customs, morals and worldview of that to modern times. Although many describe themselves as 'hardcore' polytheists, others claim that this is not just historically accurate polytheistic theology.

Current Western Polytheism

Within Western culture it is also possible to find current forms of polytheism since the end of the 20th century. Neopaganism in its different variants, such as wicca, ásatrú, neodruidism, stregheria, etc. vindicates the ancient pagan cult and seeks to revive pre-Christian Western polytheism.

In the Canary Islands (Spain), the Canarian aborigines professed a polytheistic mythology (see Canarian aboriginal religion).

Contenido relacionado

Shintoism

Deuteronomic tradition

Pius IV