Policy

Politics is the set of activities associated with group decision-making, or other forms of power relations between individuals, such as the distribution of resources or status. Also It is the art, doctrine or practice referring to the government of the States, promoting citizen participation by having the ability to distribute and execute power as necessary to guarantee the common good in society.

Can be used positively in the context of a "political solution" that is compromising and nonviolent, or descriptively as "the art or science of government", but often also has a negative connotation. For example, abolitionist Wendell Phillips stated that "no we play politics; anti-slavery is no joke to us". The concept has been variously defined, and different approaches have fundamentally different views on whether it should be used extensively or narrowly, empirically or normatively, and about whether conflict or cooperation is more essential to him. Politics is the science of power and the ability of a person or a group of people to influence the will of others even when it is against their own will.

A variety of methods are implemented in politics, including promoting one's political views among individuals, negotiating with other political subjects, making laws, and using force, including war against adversaries. The Politics is exercised at a wide range of social levels, from clans and tribes of traditional societies, through local governments, companies, modern institutions and sovereign states, to the international level. In modern nation states, people often form political parties to represent their ideas. Members of a party agree to take the same position on many issues and agree to support bills and their leaders. An election is usually a contest between different parties. A political system is the framework that defines acceptable political methods within a society.

Political science is a branch of the social sciences that deals with the activity by virtue of which a society, made up of free human beings, solves the problems posed by their collective coexistence.

Etymology

In Spanish política has its roots in the name of Aristotle's classic work, Politiká, which introduced the term from the Greek (Πολιτικά, 'affairs of the cities'). By the mid-15th century, Aristotle's composition would be translated into Early Modern English as Polettiques [ sic], which would become Politics in Modern English.

The word política is attested in the first Spanish translation from 1584 by Simón Abril of "Política" of Aristotle in turn taken from politicus, a Latinization of the Greek πολιτικός from πολίτης (polites, 'citizen') and πόλις (none: polis, lit. 'city').

Definitions

Broad concept

A broader broader definition (coined from various readings) would make us define politics as any activity, art, doctrine or opinion, courtesy or diplomacy, tending to seek, to the exercise, modification, maintenance, preservation or disappearance of public power.

In this broad definition, the object of political science can be clearly observed, understood as the public power removed from human coexistence, be it from a State, Be it from a social group: a company, a union, a school, a church, etc.

That is why when the broadest definition of «politics» is used, it is usually clarified that this is an activity that is very difficult to avoid, since it is found in almost all areas of human life.

Restricted concept

A stricter definition would propose that politics is only the officially expressed result of the laws of coexistence in a certain State.

Definition that restricts the life of non-state groups and organizations, limiting them only to the legal provisions of their States.

An opposite perspective sees politics in an ethical sense, as a willingness to act in a society using organized public power to achieve beneficial objectives for the group. Thus, subsequent definitions of the term have differentiated power as a form of agreement and collective decision, from force as the use of coercive measures or the threat of their use.

An intermediate definition, which encompasses the other two, must incorporate both moments: means and end, violence and general interest or common good. It could be understood as the activity of those who seek to obtain power, retain it or exercise it with a view to an end that is linked to the good or with the interest of the generality or people.

Gramsci conceived the science of politics both in its concrete content and in its logical formation, as a developing organism. When comparing Machiavelli with Bodin, he affirms that the latter creates political science in France in a much more advanced and complex field than Machiavelli and that Bodin is not interested in the moment of force, but in that of consensus. On the same page, Gramsci believes that the first element, the pillar of politics, "is the one in which the governed and rulers, leaders and directed really exist. All political science and art is based on this primordial fact, irreducible (under certain general conditions)"

The exercise of politics allows managing the assets of the national state, it also resolves conflicts within the societies attached to a specific state, which allows social coherence, the norms and laws determined by political activity become mandatory for all members of the national state from which such provisions originate.

Frank Goodnow makes a special emphasis on the function of politics that corresponds to the will of the State. This is complemented by its execution through the government. Politics is only functional when it allows rules to be established between the rulers and the governed, who are subjected to the will of the actions that are to be directed in order to achieve a certain goal. In turn, in the modern era, politics has managed to widen the spectrum of conflict in the private and public life of citizens, due to the desire to promote individual and collective interests.

History

The history of political thought dates back to early antiquity, with such seminal works as Plato's Republic, Aristotle's Politics, Chanakya's Arthashastra, as well as the works of Confucius.

Prehistory

Frans de Waal argued that already chimpanzees engage in politics through "social manipulation to secure and maintain influential positions. " The earliest human forms of social organization - bands and tribes - lacked centralized political structures. They are sometimes referred to as Stateless Societies.

Primitive States

In ancient history, civilizations did not have defined boundaries like present-day states, and their borders could be more accurately described as borders. Early Dynastic Sumer, and Early Dynastic Egypt were the first civilizations to define their borders. Furthermore, until the 12th century, many peoples lived in non-state societies. These range from relatively egalitarian bands and tribes to complex and highly stratified chiefdoms.

Formation of the State

There are a number of different theories and hypotheses about early state formation that seek generalizations to explain why the state developed in some places but not others. Others believe that generalizations are not helpful and that each case of early state formation should be treated separately.

The voluntary theories hold that various groups of people came together to form states as a result of some shared rational interest. The theories focus largely on the development of agriculture, and on the demographic and organizational pressure that followed and led to the formation of states. One of the most prominent theories on the early and primary formation of the state is the hydraulic hypothesis, which holds that the state was the result of the need to build and maintain large-scale irrigation projects.

The 'Conflict theories of state formation consider conflict and the dominance of one population over another to be the key to state formation. Voluntary theories, these arguments believe that people do not voluntarily agree to create a state to maximize benefits, but that states are formed due to some form of oppression by one group over another. In turn, some theories maintain that the war was essential for the formation of the State.

Ancient history

The earliest type states were Early Dynastic Sumer and Early Dynastic Egypt, which arose from the Uruk period and Predynastic Egypt respectively around 3000 BC. Early Dynastic Egypt was based around the Nile River in north-east Africa, the kingdom's borders were based on the Nile and extended to areas where oases existed. Early Dynastic Sumer was situated in the south of Mesopotamia with its borders extending from the Persian Gulf to parts of the Euphrates and Tigris.

Although state forms existed before the rise of the Ancient Greek empire, the Greeks were the first known people to explicitly formulate a political philosophy of the state and rationally analyze political institutions. Prior to this, states were described and justified in terms of religious myths.

Several important political innovations of classical antiquity came from the Greek city-states (polis) and the Roman Republic. The pre-IV century Greek city-states granted citizenship rights to their free population; in Athens these rights were combined with a direct democratic form of government that would have a long life in political thought and history.

Modern States

The Peace of Westphalia (1648) is considered by political scientists to be the beginning of the modern international system, in which external powers must avoid interfering in the internal affairs of another country. The principle of non-interference in internal affairs of other countries was expounded in the mid-18th century by the Swiss jurist Emer de Vattel. States became in the main institutional agents of a system of interstate relations. The Peace of Westphalia is said to have put an end to attempts to impose supranational authority on European states. The "Westphalian" of states as independent agents was reinforced by the rise in the thought of the 19th century of nationalism, under which he assumed that legitimate states corresponded to nations', that is, groups of people united by language and culture.

Political Science

Political science is the scientific study of politics. It is a social science concerned with systems of government and power, and the analysis of political activities, political thoughts, political behavior, and associated constitutions and laws.

Modern political science can generally be divided into three subdisciplines of comparative politics, international relations, and political theory. Other notable subdisciplines are public policy and administration, domestic politics and government (often studied within comparative politics), political economy, and political methodology. [3] In addition, political science is related to and draws on the fields of economics, law, sociology, history, philosophy, human geography, journalism, political anthropology, psychology, and social policy.

Political science is methodologically diverse, appropriating many methods originating in psychology, social research, and cognitive neuroscience. Approaches include positivism, interpretivism, rational choice theory, behaviorism, structuralism, post-structuralism, realism, institutionalism, and pluralism. Political science, as one of the social sciences, uses methods and techniques that relate to the types of research sought: primary sources such as historical documents and official records, secondary sources such as academic journal articles, survey research, statistical analysis, case studies, experimental research and model building.

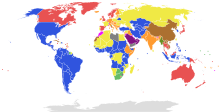

Political systems

Forms of government

Form of government, government regime or system of government, model of government, political regime or political system, are some of the various ways to name an essential concept of political science and state theory or constitutional law.

It refers to the model of the organization of constitutional power that a State adopts depending on the relationship between the different powers. The way in which the political power is structured to exercise its authority in the State, coordinating all the institutions that form it, makes every form of government need some regulatory mechanisms that are characteristic of it. These political models vary from one state to another and from one historical to another. Its formulation is usually justified by alluding to very different causes: structural or idiosyncratic (territorial, historical, cultural, religious, etc.) or conjuncture (periods of economic crisis, catastrophes, wars, dangers or "emergences" of very different nature, voids of power, lack of consensus or leadership, etc.); but always as a political illustration of an ideological project.

The denomination corresponding to the form or model of government (in addition to references to the form of State, which indicates the territorial structure) is often incorporated into the official name or denomination of the state, with terms of great diversity and that, although they provide some information on what they proclaim, they do not respond to common criteria that will define their political regime alone. For example: Plurinational State of Bolivia, United Mexican States, Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela, Kingdom of Spain, Principality of Andorra, Grand Duchy of Luxembourg, Russian Federation, Democratic People ' s Republic of Korea, United Arab Emirates or Islamic Republic of Iran. Between the two hundred states, there are only eighteen that add no more word to their official name, such as: Jamaica; while eleven only indicate that they are "states". The most common form is republic, followed by the monarchy.

There are very different nomenclatures to name the different forms of government, from the theorists of Antiquity to the Contemporary Age; at present three types of classifications are usually used:

- The elective or non-elective character of the head of State defines a classification between republics (elective) and monarchies (not elective).

- The degree of freedom, pluralism and political participation defines another classification, between democratic, authoritarian, and totalitarian systems, as permitted to a greater or lesser degree the exercise of the discrepancy and political opposition or deny more or less radically the possibility of dissidence (establishing a single party regime, or different types of exceptional regimes, such as dictatorships or military juntas); in turn the electoral system by which they have expressed in participatory systems

- The relationship between the head of state, government and parliament defines another classification, between presidentialisms and parliamentarisms (with many degrees or mixed forms between one and the other).

Political doctrines and ideologies

The concept of political doctrine, political tendency or political current can be applied both to differentiate one party or political movement from another, to differentiate subdivisions within one party or movement. Each political current is characterized by the main elements that it defends and pregone, such as the most representative of those principles and values.

Political movements and political parties are associations of freely constituted persons, and especially for political action.

- Political movements develop political action (general or specific to cases), which necessarily does not go through electoral representation in a parliament or at other levels of the state organization (municipal or provincial, counter-or advisory functions, etc.), among other things because they sometimes do not have this resource because they have not been able to access it, or because they do not.

- On the contrary, political parties exercise their political actions fundamentally through parliamentary action, real and legitimately acquired, or at least through media interventions and proselytistic acts precisely aimed at achieving some kind of representation in the institutional structure of power and government; public action and positioning at the level that is (legislative, national or communal executive, counter-lor, advisory, etc.), is an important element in the promotion and action of the principles. According to the country in question, the existence and regulation of political parties is to a greater or lesser extent, and that is why they are granted privileges and even direct financial support within certain limits. Obviously, in each case all this depends on the public freedoms and the current electoral system (see also the voting system).

All political ideologies are grouped around two dimensions: economic and social. The economic dimension is made up of two opposing ideologies, left-right, which form a horizontal line, and the social dimension is made up of two other opposing ideologies, authoritarianism-libertarianism, which form a vertical line. Together these two dimensions make up an ideological map in which we can find four great systems such as totalitarianism, conservatism, socialism and liberalism, and the point where the two lines cross is considered the political center.

However, given the emergence of current problems such as the ecological and cultural problems such as multiculturalism and globalization, various very varied authors propose other classification systems based on premises that Nolan did not foresee in his typical two-dimensional classification. There are also alternative classifications to those of Nolan elaborated by people of the Latino cultural sphere such as Andrés Ariel Luetich.

Other classifications on cultural and historical interactions

- Progressive versus romantic.

- Political Aculturation versus rejection of aculturation (globalism versus nationalisms).

Other classifications on social structure

- Collective versus individualists.

- Elitism versus pluralism (non-democratic governments versus democracies).

Other classifications on property and means of production

- Reject versus acceptance of private property.

- Productivists versus anti-productivists.

Political culture

By political culture is understood the set of knowledge, evaluations and attitudes that a given population manifests towards various aspects of life and the political system in which it is inserted. It encompasses both the political ideals and the operating rules of a government, and is the product of both the history of a political system and the histories of its members.

Political culture is a concept widely used in political science from the 1960s to the present, as an alternative model to Marxist premises about politics. In recent decades, the dissemination of studies carried out through of transnational surveys and the multiplication of case studies, have made it possible to gather systematic information on the political culture of societies of all levels of development and cultural traditions.

Policy levels

Macropolitics

Macropolitics can describe political issues that affect an entire political system (for example, the nation state) or refer to interactions between political systems (for example, international relations).

Global politics (or world politics) covers all aspects of politics that affect multiple political systems, that is, in practice, any political phenomenon that crosses national borders. This may include cities, nation-states, multinational corporations, non-governmental organizations, and/or international organizations. An important element is international relations: relations between nation-states can be peaceful when carried out through diplomacy or they can be violent, which is described as war. States that can exert strong international influence are called superpowers while less powerful ones can be called regional or middle powers. The international system of power is called the world order which is affected by the balance of power that defines the degree of polarity in the system. Rising powers are potentially destabilizing for him, especially if they show revenge or irredentism.

Politics within the limits of political systems, which in the contemporary context correspond to national borders, is known as internal politics. This includes most forms of public policy such as social policy, economic policy or law enforcement that are carried out by the state bureaucracy.

Mesopolitics

Mesopolitics describes the politics of intermediate structures within a political system, such as national political parties or movements.

A political party is a political organization that typically seeks to achieve and maintain political power within government, typically by participating in political campaigns, educational outreach activities, or protest actions. Parties often embrace an expressed ideology or vision reinforced by a written platform with specific objectives, forming a coalition between disparate interests.

The political parties within a particular political system together form the party system which can be multi-party, two-party, dominant-party, or single-party, depending on the level of pluralism. This is affected by the characteristics of the political system, including its electoral system. According to Duverger's law, “first to the post” systems are likely to lead to two-party systems, while proportional representation systems are more likely to create a multi-party system.

Micropolitics

Micropolitics describes the actions of individual actors within the political system. This is often described as political participation. Political participation can take many forms, including:

- Activism

- Boycott

- Civil disobedience

- Demonstration

- Request

- Pickets

- Strike

- Fiscal resistance

- Vote (or its opposite, abstentionism)

Political values

Democracy

Democracy (from late Latin democrat, and this of the Greek δημοκρατία dēmokratía) is a form of social and political organization that attributes the ownership of power to the whole of citizenship. In a strict sense, democracy is a type of organization of the State in which collective decisions are adopted by the people through mechanisms of direct or indirect participation that confer legitimacy on their representatives. In the broad sense, democracy is a form of social coexistence in which members are free and equal and social relations are established according to contractual mechanisms.

Democracy can be defined from the classification of the forms of government made by Plato, first, and Aristotle, then, in three basic types: monarchy (government of one), aristocracy (government "of the best" for Plato, "of the least", for Aristotle), democracy (government "of the multitude" for Plato and "of the most", for Aristotle).

There is indirect or representative democracy when political decisions are adopted by people recognized as their representatives.

There is participatory democracy when a political model is applied that facilitates citizens ' ability to associate and organize in such a way that they can exert a direct influence on public decisions or when broad consultative plebiscite mechanisms are provided to citizens.

Finally, there is direct democracy when decisions are taken directly by members of the people, through plebiscites and binding referendums, primary elections, facilitation of the popular legislative initiative and popular vote of laws, a concept that includes liquid democracy.

These three forms are not exclusive and are often integrated as complementary mechanisms in some political systems, although there is always a greater weight of one of the three forms in a particular political system.

It is not necessary to confuse the republic with democracy, because they refer to different principles. According to James Madison, one of the founding fathers of the United States: "The two great points of difference between a democracy and a republic are: first, the government delegation, in the latter, to a small number of citizens elected by the rest; secondly, the largest number of citizens, and the largest sphere of the country, on which the latter can be extended."Social equality

Social equality is the characteristic of those states in which all their individuals or citizens without exclusion, in practice achieve the realization of all human rights, primarily civil and political rights, as well as the economic, social and cultural rights necessary to achieve true social justice.

Social equality entails the recognition of equality before the law, equal opportunities and equal civil, political, economic and social outcomes.

Social equality is the opposite of social inequality - economic inequality, slavery, racism, sexism, caste society and strata - as well as any other kind of discrimination based on gender, ethnicity, sexual orientation, resources, religion, biological species, language, age, disability - physical or intellectual - or any other personal status.Freedom

Political freedom (also known as political autonomy or political agency) is a central concept in history and political thought and one of the most important characteristics of democratic societies. Political freedom was described as the absence of oppression or coercion, the absence of disabling conditions for an individual and the fulfillment of enabling conditions, or the absence of coercive living conditions, for example, economic coercion, in a society. Although political freedom is often referred to as negatively interpreted as the absence of unreasonable external restrictions on action, it can also refer to the positive exercise of rights, capacities and possibilities of action and the exercise of social or group rights. The concept can also include freedom from internal restrictions on action politics or discourse (for example, social conformity, consistency, or inauthentic behavior). The concept of Political freedom is closely related to the concepts of civil liberties and human rights that in democratic societies usually enjoy legal protection by the State.

Political dysfunction

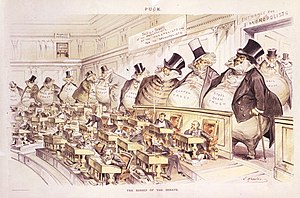

Political corruption

Political conflict

Contenido relacionado

Labor movement

Fernando Henrique Cardoso

Sofia from Greece