Po

The River Po [pɔ] (Latin: Padus and Eri ancient place: Bodincus or Bodencus; in ancient Greek: Πάδος and Ἠριδανός', Eridanos) is a long river in northern Italy that flows west to east from the Cocian Alps to the Adriatic Sea, where it empties into a wide delta near and south of the city of Venice. It is 652 km—or 691 km considering the Po-Maira system, a tributary of the right bank—, making it the longest river entirely through Italian territory. It drains a hydrographic basin of 74,000 km², of which about 71,057 km² is Italian territory, a quarter of the country —41,000 km² in mountainous environments and 29,000 km² plain—, making it the largest Italian basin (the rest of the basin is Swiss and French territory). It is also the largest Italian river —either by minimum flow (absolute 270 m³/s), medium (1540 m³/s) or maximum (13 000 m³/s)— and also by average flow the fifth European river (except the Russians, after the Danube, Rhine, Rhône and Dnieper)[citation needed] (the Po is characterized by its great flow and many rivers of more than 1000 km have less flow). The Po, at its widest point is 503 m and runs generally along the 45th parallel north.

The Po crosses or borders 14 provinces —from its source to its mouth, Cuneo, Turin, Vercelli and Alessandria (Piedmont region), Pavia, Lodi, Cremona and Mantua (Lombardy region), Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia and Ferrara (Emilia-Romagna region) and Rovigo (Veneto region)— and bathes or crosses 183 communes. It marks the regional border for long stretches, between Piedmont, Lombardy, Emilia-Romagna and Veneto. Its basin is of interest to about 3,200 communes in seven regions —in addition to those it runs through, Valle d'Aosta, Liguria, Tuscany and the Autonomous Province of Trento— and there are 450 lakes in it that drain through the Po and /or its 141 tributaries (among them Lakes Maggiore, Lugano, Como and Garda). The river flows through Turin - capital of the Piedmont region - and passes next to Piacenza, Cremona and Ferrara - the three provincial capitals -. In addition, it is connected to Milan through a network of canals called navigli that Leonardo da Vinci helped design.

The head of the Po is a spring located at an altitude of 2022 m that seeps from a stony slope in Pian del Re, in the Piedmontese municipality of Crissolo, on a terrace at the head of the Val Po, below the northwest face from Monviso (in the Cocian Alps). Near the end of its course, a wide fluvial delta is created (with hundreds of small channels and five main branches, called Po di Maestra, Po della Pila, Po delle Tolle, Po di Gnocca and Po di Goro) in whose southern part is Comacchio, an area famous for eels. The Po Delta, due to its great environmental value, was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1999 as part of "Ferrara, City of the Renaissance and its Po Delta".

The river is subject to heavy flooding and more than half its length is controlled by argini, or dikes. The slope of the valley decreases from 0.35% in the west to the 0.14% in the east, a low gradient. In most of its course, the Po runs through flat territory, which is why it takes its name (plain or valley of Padano). Currently, the Po is navigable for about 389 km from the mouth of the Ticino to the sea. There are active commercial shipping services from Cremona to the sea (292 km).

Due to its geographical position and the historical, social and economic events that have taken place around it since Antiquity —the Po Valley was already part of Roman Cisalpine Gaul and its course divided it into Cispadan Gaul (already south of the river) and the Gaul Transpadana (north of the river)—to this day, the Po is recognized as the most important Italian river. On its banks 40% of the gross domestic product is formed, 37% of the national industry is concentrated —which supports 46% of the jobs—, 35% of agricultural production, 55% of animal husbandry and 48% of the national electrical energy is consumed. It is therefore a nerve center for the entire Italian economy and one of the European areas with the highest concentration of population, industries and commercial activity.

Hydronym

The river Po was already geographically known in ancient Greece under the name of Eridanós (in ancient Greek: Ἠριδανός, in Latin: Eridanus; in literary Italian Eridano); originally used as a synonym for a mythical river, which would appear more or less south of Scandinavia, and which would have formed after the last European ice age (Würm).

The first historical sources are in the Greek Theogony of Hesiod (6th century BC), cited as the name of one of the many children of the Titan Oceanus and the nymph Thetis, and of the which derive various names from European rivers. This name was later taken up by the historian Polybius in the 2nd century BC. C., where Eridanus was one of the sons of Phaethon, fallen into a river during a chariot race, enough to attribute the gates of Hades, and hell according to Greek mythology, but also the title of a prince dedicated to Egyptian cults, a figure that often appears in the ancient legends about Turin.

However, the name would have even older roots; In both Akkadian and Sumerian, but also in other Semitic roots, eridu would generically mean a place or city of command located near a river, citing, for example, the homonymous city of Eridu in the region of Mesopotamia dated to the 20th century B.C. c.; in parallel, other historical sources say that a small Eridu was also built near the Po delta, on the Adriatic Sea. On the other hand, the name Eridanus contains the ancient Semitic root *rdn, which is common to some other river names such as the Rhône, Rhine, Dan ubio, Giordano (Jordan). In addition, in ancient Greece there was a small river called Eridano (for a long time dry), which arose from the heights of eastern Attica and flowed into the Aegean Sea through the Ceramicus necropolis, south of the city of Athens.

For the Celts-Ligurians, who only appeared in the region from the 9th century B.C. C., the name of the Po was Bodinkòs or Bodenkùs, from an Indo-European root (*bhedh-/*bhodh- ) indicating 'dig' or 'make deep', the same root from which the current Italian terms of "fossa" ('ditch') or "fossato" ('well') derive, alluding to the entire geographical depression of the Padano fluvial area. Thus, the old Latin name Padus —hence the adjective Padano— would derive, according to conventional wisdom, from the same root as bodinkòs; according to others, however, it would derive from another Celtic-Ligurian word pades, which would indicate a resin produced by a variety of Scots pines particularly abundant near the source of the Po.

The Italian name "Po" is obtained by contraction of the Latin Padus > Paus > Pàu > Po. In other Slavic languages (Czech, Slovak, Polish, Slovene, Serbian, Croatian), but also in Romance languages, such as Romanian, it is still often used to call Po Pad or Padus . In the same way, among the Italian adjectives, which generally inherit the old Latin root, the words paduano and padano still survive, which apply to the Padan plain and give name to Padania, whose use has been politically extended since the 1990s.

History

Prehistory and Antiquity

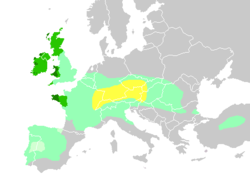

Nucleus of Hallstatt territory, towards the sixth century BC. Maximum Celtic expansion, ca. 275 a. C. The lusitana area of Iberia where the Celtic presence is uncertain. The 6 Celtic nations that maintained a significant number of Celtic speakers in the Modern Age. Areas where Celtic languages are still spoken today.

Urban development began in the Po Valley much later than in southern Italy or Greece. The first known inhabitants of the thick forests and swamps were the Ligurians, an Indo-European people. Later, in the seventh century B.C. C., the progressive migration of the Insubres, a Celtic people (hence the name Insubria, which is sometimes designated the northwest of Lombardy) arrived and the southern and central parts of the valley were conquered and colonized by another pre-Indo-European people, the Etruscans, who left such names as Parma, Ravenna and Felsina, the ancient name of Bologna. Etruscan rule left important marks and introduced urban civilization, but it was short-lived. When the fifth century B.C. C., a new Celtic horde swarmed through the passes of the western Alps and conquered most of the Po Valley. This invasion from the north did not reach Veneto: its inhabitants, the Veneti, were likely a distinct group who, being skilled traders, were culturally influenced by both Etruscans and Greeks at the time.

The Gallic conquerors, divided into important tribes such as the Boii (from which Bononia, present-day Bologna, derives), the Taurines (hence the name of Turin), the Cenomanians and the earlier Insubres they lived mainly in the plains, while incorporating the populations of the Alps. A warlike people, they even attacked and burned Rome itself in 390 B.C. C. under a leader named Brennus. Roman revenge took time, but it was complete and final: the Celtic languages disappeared from northern Italy, being replaced by the Latin culture. This transformation occurred after the victory of the Republic of Rome over the Gauls at the Battle of Clastidio (222 BC) and after Hannibal's final defeat at the Battle of Zama around 196 BC. By BC, Rome already mastered the woody plains and soon displaced the Etruscans, dotting the region with lively colonies, clearing the forests to make way for new land, fighting off the last rebellious tribes and gradually imposing its own civilization.

The centuries of Roman domination forever decided the main aspect of the Po Valley. The cities were located in two stretches of the areas at the foothills of the Alps and the Apennines: in the south, they continued along the Via Emilia; in the north, along the route between Milan and Aquileia. Julius Caesar granted Roman citizenship to the peoples of these lands, from where he recruited many of his bravest troops. The Po Valley was for a time the seat of the capital of the Western Roman Empire, in Mediolanum, between 286-403, and then in Ravenna until its final political collapse. The region was attacked in the 3rd century century by Germanic tribes who broke through the Alps and was then sacked two centuries later by Attila. Led by their king Theodoric the Great, the Ostrogoths conquered the region from the north in the closing years of the V century, deposing Odoacer, the barbarian ruler of Italy, who had succeeded the last Western Roman Emperor (see reign of Odoacer).

Middle Ages

The Gothic war (535-554) and Justinian's plague (541-543) devastated the Padan population. In this desolate setting, many people had fled to the mountains for their safety (remaining quite populated until the XX century).), the Germanic Lombards arrived, a warrior people who gave their name to almost the entire Po Valley: Lombardy. In the Middle Ages the term was used to indicate all of northern Italy. The Lombards divided their domain into duchies, which often contended for the throne; those of Turin and Friuli, in the extreme west and east, respectively, seem to have been the most powerful; meanwhile, the capital soon changed from Verona to Pavia. Monza was also an important city at the time, more so than the already ruined Milan. The rigid rule of the Lombards, who behaved almost like a superior caste over the natives, softened somewhat with their conversion from Arianism to Catholicism.

The Lombard kingdom was overthrown in 774 by Charlemagne and his Frankish armies, becoming a prized part of the Carolingian Empire. The assertion of large land ownership in the 8th/9th centuries accelerated the process of land reclamation and intensification of land use, transforming the landscape of the Po Valley. After the chaotic feudal dissolution of the empire and the many In strife between claimants to the imperial crown, Otto I of Saxony set the stage for the next phase of the region's history by incorporating the Po Valley in 962 into the Holy Roman Empire of the Germanic nation. In Veneto, in Venice, the capital located on the lagoon, a great maritime power arose in alliance with its former masters, the Byzantine Empire. Over time communis arose as cities prospered in trade. Soon Milan became the most powerful city in the central plain of Lombardy itself, and despite having been razed to the ground by Germanic imperial troops in 1162, it was the Milan-led Lombard League, with papal blessing, that defeated the emperor. Frederick Barbarossa at the Battle of Legnano in 1176.

Other civil wars intensified with the reciprocal bloodbaths of the Guelphs and Ghibellines of the 13th century and XIV. The Signorie came from communal institutions. In the first half of the XV century, with the expansion of Venice, in the eastern mainland, and with the supremacy of Milan In the center and west of the region (which was not diminished significantly by the Black Death of 1348), unprecedented levels of prosperity were reached. Vast areas were irrigated and cultivated with the most modern techniques then available. The average population is estimated to be around 50 people per square kilometer, a very high level for those times.

Early Modern Age

In 1494 the ruinous Italian Wars between France and Spain began, which lasted for a few decades. The land changed hands frequently. Even Switzerland received some Italian-speaking lands in the north (the Canton of Ticino, which is technically not a part of the Padana region), and Venetian rule was challenged, forcing Venice to neutrality as an independent power. In the end, Spain prevailed with the victory of Charles V over Francis I of France at the Battle of Pavia in 1525.

Spanish domination was oppressive, adding its burden to the Counter-Reformation imposed by the archbishopric of Milan; Protestantism was fought and could not establish itself in the area. Burning at the stake became a common practice during witch hunts, especially in the neighboring Alpine lands. During this dark period, however, the Lombard industry recovered, especially the textile branch, its mainstay. Following the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1713) and the cession of Milan to Austria, government and administration improved significantly, although the peasantry began a century-long slide into misery, the cities grew and prospered.

When Napoleon I entered the Po Valley during some of his most brilliant campaigns (in 1796 and in 1800, culminating in the historic battle of Marengo), he found an advanced country and made it his kingdom of Italy (1805-1814). With the final defeat of Napoleon the Austrians returned, but were no longer welcome. In the west, in Piedmont, the House of Savoy would emerge to serve as a springboard for the unification of Italy.

Late Modern and Contemporary Ages

The Risorgimento, after a failed start in 1848 and 1849, triumphed ten years later in Lombardy, which was conquered by a Franco-Piedmontese army. In 1866 the Veneto joined the young Italy, thanks to the defeat of Austria against Prussia. Rural poverty increased emigration to the Americas, a phenomenon that continued in the central region until the end of the 19th century, but which persisted in Veneto well into the XX century. Industry grew rapidly, thanks to an abundance of water and a literate workforce.

The World Wars did not significantly damage the area, despite the destruction caused by Allied aerial bombardment of many cities and heavy fighting on the front lines in the Romagna. The Resistance protected the major industries in the region, which the Third Reich was using for war production, preventing their destruction: on April 25, 1945, a general insurrection in the wake of German defeat was highly successful. Most of the cities and towns, in particular Milan and Turin, were already liberated by the partisans days before the allied troops arrived.

After the war, the Padana area led the Italian economic miracle of the 1950s and 1960s. Since 1989, the Northern League, a federation of northern regionalist parties, has promoted both secession and greater autonomy for the area of Pada called Padania.

Historical evolution of the mouth on the Adriatic coast

Antiquity

Around the 10th century B.C. C. the Adriatic coastline was withdrawn about 10 km compared to today. The Po entered the sea with two estuaries: to the north, it ended near the current Chioggia, while to the south it drained at a point equidistant between the current cities of Ferrara and Ravenna. The river divided into two branches at the height of the current municipality of Ficarolo.

In the sixth century B.C. C. the Greeks founded the emporium of Adria on the northern branch of the Po (Po di Adria) and, in a short time, began to call the entire northern part of the Adriatic Sea Adrias Kolpos. Later, the Etruscans founded the city of Espina on the southern branch. Meanwhile, over time, there had been a change in the water regime that gave more prominence to the southern channel of the river. Between protohistory and the Roman age, the branch of the Adria was reduced while the southern branch increased. The fate of the two cities shows it: while Adria was experiencing a period of crisis, Espina was reaching its maximum splendor. The Po, in Adria, was buried within the space of a few centuries.

Perhaps due to the great influx of water, the spinetic branch doubled: the Olana (now Po di Volano) and the Padoa (from which the name Po could derive) were born. Fossil evidence remains of the then coastline, the main one being the Agosta embankment (Argine Agosta), in the interior of Valle del Comacchio. The Olana flowed further north from Espina and also had an additional branch that headed north and from which the section called Gaurus (from which the current names Goro and Codigoro derive) was born and emptied near the current Mesola; the fossil dunes of Massenzatica, to the south, and those on the other side of San Basilio, bear witness to the position of the ancient mouth.

In Roman times the most important river ports on the Po were those of Cremona, Piacenza, Brescello, Ostiglia, Vicus Varianus (present-day Vigarano Mainarda) and Vicus Hobentia (the current Voghenza). Descriptions of the river from three famous Roman authors have been preserved:

- Plinius the Old said that the Po was navigable to Turin, as its main tributaries were also navigable.

- Polibio said that the Po dates back about 2000 stadiums (i.e., about 355 kilometers, up close to the Tanaro) from the ancient mouth of the Volano. He described the place of Trigaboli, where the Po was divided into two branches: that of Olana and that of Padua. Trigaboli derives from Three gabuliThree Corps, probably the current Codrea. Waters up the fork should be a port called Bodencus. Bodencus or Bodincus, a Celtic word of ligur origin which means "deep" and which was also used to designate any river.

- Estrabón noted that to go from Piacenza to Rávena following the course of the Padus It took two days and two nights. Rávena, located at the southern end of the delta, was connected to the spinal branch through the Fossa Messanicia, a channel of 18 km.

Middle Ages

In the Middle Ages the main branch of the delta was already constituted by the current Po Morto di Primaro, which had been formed in the century VIII a little south of the Padoa, and running south of the Valli di Comacchio. Since the mid-18th century century, this branch formed the tail end of the Reno River (also once a tributary of the Po) in which Reno himself was transported as a result of the creation of Cavo Benedettino.

Also the Po di Volano, which flows in Ferrara, was one of the two main courses: this situation lasted until 1152, the year of the Rotta di Ficarolo. As a result of the heavy and frequent rains, the river broke the north dike near the confluence of both arms, in Ficarolo, in what was then Transpadana Ferrarese; the course of the river was modified and gradually began to take its current shape.

The new section was shorter than the others, and for this reason the water flowed through it faster, giving rise to the main course called Po di Tramontana and then Po di Venezia, turning off the Po di Volano at Pontelagoscuro, a few kilometers north of Ferrara.

Modern Age

Between 1600 and 1604 the Republic of Venice, despite the protests of the Papal States, diverted the final stretch of the course of the Po to prevent the delta from moving and flooding the lagoon. The works, which were called & #34;taglio di Porto Viro" ('Corte de Porto Viro'), began on May 5, 1600 and were completed on September 16, 1604. This modification extended the delta to the east in a few years to form new territories included in the current Po delta, partially burying the sacca di Goro. From north to south, the branches of the Po di Levante, Po di Maistra, Po di Pila, Po delle Tolle , Po di Gnocca and Po di Goro (which already existed, but was doubled in length). In addition, to the south and north of the current delta, in the coastal areas then deprived of sediment supply, in addition to the phenomenon of subsidence, the erosion of the coastal dune belt and beaches became more acute.

A 1693 map patella Po di Venezia to the northern fork of the Po di Goro. Continuing east and close to Donada, the same branch is spelled Po delle Fornaci.

The Po di Levante, during the great improvements carried out in the 1930s to protect the Fissero-Tartaro-Canalbianco waterway, was disconnected from the Po di Venezia, remaining connected through the Volta Grimana navigation lock, becoming the terminal section of the Canalbianco.

The Po di Volano reaches the sea through a small estuary that flows into the Goro.

Geography

Course Description

Course in Piedmont

The Po River rises in the Piedmont region, in the province of Cuneo, very close to the border with France. Its source is in the Cocian Alps on a terrace at the head of the Val Po, in a spring located at an altitude of 2022 m that seeps from a stony slope near the town of Pian del Re (commune of Crissolo), below the northwest face of Monviso (3841 m). A large rock with an inscription—"QUI NASCE IL PO"—now indicates that origin. Enriched by the contribution of countless other sources (it is not a mistake to say that "the Monviso itself is the source of the Po"), it begins to flow impetuously in the valley of the same name. This area is considered as Pian del Re Natural Reserve integrated into the Parco della fascia fluviale del Po - cuneese section (established in 1990 and protecting 7780.14 ha).

In the first part of its course, the Po is a typical mountain stream, which runs fast through the bottom of a valley with the typical U shape of glacial valleys, with steep slopes and a rounded bottom. The river soon heads east, passing through Crissolo (174 hab.), Ostana (74 hab..) and then Paesana (2784 hab.), where there is already a continuous narrow band of agricultural areas some 610 m s. no. m., sandwiched between two wooded slopes of the Rocchetta basin, bordering Mount Bracco (1306 m), an important geological formation and interesting archaeological, historical-architectural and natural site.

Near Revello (351 m s. n. m.) the Po already comes out of the mountains, the valley widens out to a wide plain, and the river head north: only 13 km in a straight line separate the sources of the Po from this plain, a distance in which it has lost almost 1900 m. Enter the “Nature Reserve of the confluence with the Bronda” (Riserva Naturale della confluenza con il Bronda) and the “Living Fish Bridge Equipped Area” (Area Attrezzata del Ponte dei Pesci Vivi). Something happens north of Saluzzo (17,057 inhab. in 2014), where the river already has the characteristics of a slow and lazy plain river. Slow waters support more species and allow for more complex riparian life. On the bridge of the SS 623 , with one of the iconic images of it, distant Monviso is reflected in the now wide Po River. After the confluence with the short Ghiandone stream (23.8 km), the course of the Po River becomes deeper and more regular, with an abundant flow that It allows navigation throughout the year with canoes and the typical barche a punta. In its course, on the left bank, is the Abbey of Santa Maria di Staffarda, an ancient monument built by Cistercian monks in 1135 and, beyond, on the plain, the spur of the Rocca di Cavour Nature Reserve. In the Middle Ages these once swampy lands were drained to make them productive.

- El Po in the province of Cuneo

Then the Po passes through Cardè (1124 inhabitants) and begins a section that will be the provincial boundary, between Cuneo, to the southeast, and Turin, in the northwest. In this section it immediately reaches Cantogno, Villafranca Piedmonte (4764 hab.) and Faule (489 hab.), where it meets the Torrente Pellice, in an area protected as the “Nature Reserve of the Pellice confluence” (Riserva Naturale della confluenza del Pellice, at 247 m s. n. m.), near Polonghera (1160 inhab.). Attached to the protected area is the last nature reserve of Cuneo, already only 241 m s. no. m. altitude, at the confluence with the Varaita (92.4 km), a tributary that comes from the right. Then, after passing through Casalgrasso (1449 hab.), it reaches the small Lombriasco (1075 hab. span>), already on the border with the province of Turin, where it also receives from the right the Maira stream (111.1 km), near the city from Carmagnola (29,033 hab.). The inhabited centers of these lowlands preserve valuable testimonies of the works linked to the use of water by man for centuries: mills, bealere, pipes, closed stone.

The Po enters the province of Turin, receiving the short Meletta on the right (26.4 km) and then passing through Carignano (9258 hab.), La Loggia (8930 hab.) and the city of Moncalieri (57,120 inhab.), already in the metropolitan area of the Piedmontese capital and where the Moncalieri castle of the same name stands out, built in the 12th century and enlarged in the 15th century, which is part of the World Heritage Site (Royal Residences of the House of Savoy). In Moncalieri it receives, on the left, first, the Chisola torrent (39.4 km) and when it comes out the Sangone (46.1km); and to the right, two short torrents, the Banna (28 km) and the Tepice (17.6 km).

The Po then enters the city of Turin (890,385 inhabitants) arriving from the south and despite not having traveled more than a hundred kilometers from its sources, it is already an important stream with a large channel about 200 m wide and with an average discharge of about 100 m³/s. After skirting the center of the city, it receives, coming from the west and to the left, the rivers Dora Riparia (101.09 km) and Stura di Lanzo (68.8 km), two rivers that provide water from the alpine area of Gran Paradiso. On the banks of the Po is another residence of the royal house of Savoy, also a World Heritage Site, the Valentino castle. Right at the confluence of the Stura di Lanzo is the first major river island in its course, the Isolone di Bertolla, which is almost 2.5 km long.

- The Po in Turin

Leaving Turin behind, the Po passes through San Mauro Torinese (18,925 inhabitants), where the Luigi Einadi river park is and where the Cimeno dam allows divert water, on the right, to the Cimeno canal. The Po continues bordering Settimo Torinese (47,785 hab.), Piana San Raffaele and Brandizzo (8,297 hab. ). It receives the Malone stream (47.72 km) and the Orco stream (89.5 km), who approach it almost together from the left, in an area protected as the “Special Nature Reserve of the confluence of the Orco and the Malone”. On the banks of the Orc is an Esso petrochemical depot that can store 36,000 m³. Shortly after the Po, it reaches the city of Chivasso (26,728 inhabitants), where the Cavour channel is born, a long channel of 83.2 km that diverts waters from the left bank and heads northeast for crop irrigation, especially rice, and ends up draining into the Ticino River. Right at the canal bypass is the Chivasso thermoelectric plant, owned by ENEL, a combined cycle gas plant renovated in 2015 to reduce its emissions. Then the Po turns east, following a section in which its banks become protected in the "Parque fluvial del Po y del Orba", with several more natural reserves, including the one at the confluence of the Dora Baltea (160km).

Here the river will mark the provincial boundary in a stretch between the provinces of Turin, to the south, and Vercelli, to the north. In this section of the border, it reaches Crescentino (7,984 inhabitants) and then passes in front of the Enrico Fermi Nuclear Power Plant, built in 1961–1964, which has a single 260 MW reactor, currently being dismantled by SOGIN. After passing through the small town of Trino (7,345 inhabitants), it enters the province of Alessandria, in the historical-geographical region of Monferrato, which in 2014, it was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO as part of the "Piedmont Wine Landscape: Langhe-Roero and Monferrato". The Po briefly crosses the Monferrato in its northern part, entering the plain of Vercella. Arrive immediately at Pontestura (1485 hab.), Morano sul Po (1530 hab.) and Casale Monferrato (34,437 inhab.). In this section, on the right, you will find the Stura del Monferrato (36.7 km). It continues along Frassineto Po (1463 hab.) and is later reinforced by the contribution of the Sesia river (138 km), which approaches it from the left bank, arriving from the north, at the provincial border between Vercelli and Pavia, the Po beginning to have majestic dimensions.

- The Po in the Piedmont after Turin

Piedmont-Lombardy regional limit course

After this confluence with the Sesia, the Po turns almost to the south, in a section that will mark, for several tens of kilometers, the limit between the regions of Piedmont (province of Alessandria, to the south) and Lombardy (province of Pavia, to the north). The river continues its slow progress passing through Breme (AL) (872 hab.), where an important abbey was founded in 929 and has survived to this day. The left bank is part of the historical-geographical region of Lomellina, located opposite the last foothills of Monferrato, on the western bank, which the Po skirts passing at the foot of Valmacca (1040 rooms), Bozzole (326 rooms, Pomaro Monferrato (386 rooms.), small towns all located, then comes Valenza (19,178 hab.) a historic city that changed hands many times throughout the of history between Italians, Spanish and French.

After passing through the «Garzaia di Valenza Integral Natural Reserve», the Po heads definitively towards the east and passes a short distance from Frascarolo (1241 hab.), where a good medieval castle is still preserved, which has already lost its original defensive stamp. It is followed by Mugarone (1,772 inhab. in 2010) and Bassignana (1,772 inhab.) and then, thanks to the contribution of the Tanaro River (276 km), its main tributary from the right that approaches it coming from the south, already has a large flow (more than 500 m³/s). Pass by the small towns of Capraglia, Isola Sant'Antonio (742 hab. in 2011) and Cornale (747 inhab. in 2010), where it receives from the right the small Scrivia stream (117.2 km), at a point marked the place where the Po becomes fully Lombard, entering the province of Pavia.

Course in Lombardy

Already in the province of Pavia, almost opposite the mouth of the Scrivia, on the left bank, is the confluence with the Agogna (140 km), in the small town of Balossa Bigli in the commune of Mezzana Bigli. Leaving Ghiaie behind, it meets the Staffora River (65 km) on the right. The A7 Autostrada (Genoa-Milan) then crosses the Po, which continues through the small towns of Mezzana Robattone, Bastida Pancarana (1,047 inhab. in 2010) and Mezzana short. Then, on the right, it receives the short and scarce Coppa stream (32 km), in Bressana Bottarone (3560 inhabitants. in 2010). In Mezzanino (1,509 inhab. in 2010) the small Scuropasso stream flows to the right (30 km ) and shortly after, in Vaccarizza, it receives, from the left, the Ticino river (248 km), the river that bathes the capital Pavia located to the north, less than 4 km from the course of the Po. The Ticino is its main tributary by volume of water and makes the Po navigable (thanks to its flow being more than 900 m³/s) also for large ships to the mouth. The Po continues its advance, and after receiving from the right in Portalbera (1,577 inhabitants in 2010) the short Versa stream (12 km), it passes in front of San Zenone al Po (625 inhabitants in 2010), where it receives the short Lower or southern Olona (36 km) (not to be confused with the nearby and longer Olona, a tributary of the Lambro). It then continues through Parpanese, where its course once again becomes the regional limit.

Lombardy-Emilia-Romagna regional limit course

The course of the Po once again marks the regional boundary, this time between Lombardy, to the north, and Emilia-Romagna, to the south. After first receiving the Tidone torrent on the right (47 km), from the confluence in Orio Litta on the left with the Lambro river (130 km), the Po is the Lombard limit of the Province of Lodi. It then turns right into the Trebbia river (118 km) just before entering Piacenza (102,191 hab.. in 2015), the provincial capital and most populated city in this section. Follow Mortizza and then take the river Nure (75 km) to the right. Shortly after, it passes another nuclear power plant, the Caorso nuclear power plant (the most powerful and modern in Italy in its day, closed in 1990 by popular decision after the 1987 referendum and since 1999 under dismantling by SOGIN like the one in Trino)., located at the confluence with the Chiavenna torrent (52 km), which also comes from the right. After passing through the town of San Nazzaro, it reaches the island of Serafini, in Castelnuovo Bocca d'Adda, but which extends for about 10 km² in the municipality from Monticelli d'Ongina. It then receives, on the left bank and on the northern shore of the island, the river Adda (313 km), a point that marks the entry into the province of Cremone. It then immediately reaches the provincial capital, Cremona (71,901 inhabitants in 2016), another of the important cities of this middle section, where it crosses a series of channels called navigli, which give the area a very characteristic aspect.

The Po then receives, on the right bank, the river Arda (56 km), at a point that marks the border between the provinces of Piacenza and Parma and shortly before passing Polesine Parmense (1,432 inhab. in 2014). It continues through Zibello (1833 inhab. in 2014) and Isole Pescaroli and then approaches it, from the right and coming from the Genoese Apennines, the river Taro (126 km) in small Gramignazzo, commune of Sissa. The Po continues through Casalmaggiore (15,407 inhab. in 2014), Isolone and Cicognara, almost opposite the mouth of the Parma torrent (92 km), which approaches the Po from the right coming from the south and after having passed through the homonymous provincial capital, Parma (193 343 hab. in 2016), located about 20 km from Po. It then leaves the Po on the north bank of the Lombard province of Cremona and enters the province of Mantua. It then goes through Viadana (20,083 hab. in 2014), Brescello and Boretto (5,315 hab. in 2014), where it receives, from the right, the river Enza (93 km). Follow Guastalla (15,225 inhabitants in 2015), located just after having received the Crostolo stream on the right bank (55km). After passing through Luzzara (9,318 inhabitants in 2014), its course ceases to be a regional limit to fully enter the province of Mantua, again entirely in Lombardy.

- The Po at the Lombardy-Emily-Roman limit

Course in Lombardy (2nd section)

The Po continues its advance through the province of Mantua and, after passing in front of Suzzara (21,129 inhabitants in 2014) and small Cizzolo, it receives, on the left, to the Oglio river (265 km), in an area protected since 1988 as a regional park, the Parco dell'Oglio Sud. the towns of Borgoforte (3562 inhab. in 2010), Moteggiana, Portiolo, San Giaccomo Po, San Benedetto Po (7486 inhab. in 2014) and Correggio Micheli. Then it receives, also from the left, the Mincio river (75 km, but which reaches 194 km, considering the Sarca-Lake Garda-Mincio system). After receiving the Secchia river on the right (172 km), the Po continues through Ostiglia (6830 hab. in 2015), Revere (2594 inhab. in 2010), and Borgofranco sul Po ( 803 inhab. in 2010), where the river once again becomes the regional boundary, this time between the Lombard province of Mantua and the Venetian province of Rovigo.

Lombardy-Veneto regional boundary course

The Po continues its slow progress towards the east, reaching the small towns of Carbonara di Po, Bergantino (2,572 inhabitants in 2014), Carbonara di Po (1,344 inhab. in 2010) and the Castelmassa twins (4,287 inhab. in 2014) and Sermide (pop. 6,428 in 2010), facing on either side of the Po. After passing in front of Stellata, the Po once again becomes the regional limit, again of Lombardy, although this time with the Veneto, with the province of Ferrara, in the south. At Stellata the Po branched off into a branch of the ancient delta, now fossilized, of the Po di Volano, which runs through the city of Ferrara and empties into the Lido di Volano. This branch is now almost completely canalised.

Emilia-Romagna-Veneto regional limit course

As soon as it enters the province of Ferrara, it receives the Panaro River (148 km) on the right bank, almost at the mouth of the Cavo Napoleonico, a 18 km canal begun to be built between 1806-1814 (although completed in 1954-1963) that connects with the Reno River. With an almost horizontal outline and sufficient width, it works as a bidirectional spillway that can evacuate between both basins up to 1000 m³/s. Then the Po continues, reaching Ravalle, Zampine, Occhiobello (11,915 inhabitants in 2014), Santa Maria Maddalena and its twin Pontelagoscuro. Here, the Boicelli canal connects the Po with the capital Ferrara (133,155 inhabitants in 2016), located less than 4 km to the south, on a route that corresponds to the old course of the Po di Volano. Then the Po reaches Francolino, Fossa d'Albero, Alberone, Polesella (4075 hab. in 2014), Crespino (1910 pop. in 2014), Villanova Marchesana (964 pop. in 2014) and Berra (4954 inhab. in 2014). From here the Po splits in two, following the main river to the east and the branch of the Po di Goro going south, leaving between the two the great island of Ariano, an alluvial island of 178 km². This point is considered the beginning of the Po delta.

- The Po at the Emilia-Roman-Véneto boundary

Course in Veneto

Here the river begins its wide delta (380 km²), in which it will divide into five main branches (Po di Maestra, Po della Pila, Po delle Tolle, Po di Gnocca and Po di Goro) and 14 mouths; an additional secondary branch (the Po di Volano) that runs through the city of Ferrara, is now inactive. The great river then empties into the Adriatic Sea, crossing the territories belonging to the municipalities of Ariano nel Polesine, Goro (3828 inhab. in 2014), Porto Tolle, Taglio di Po and Porto Viro. The river delta, due to its great environmental value, has been declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO.

The main branch of the Po ceases to be a regional boundary and fully enters the province of Rovigo, in a section that is entirely part of the Venetian Po Delta Regional Park. The main course continues in this final section passing in front of Corbola (2,461 inhabitants in 2014), Curicchi, Mazzorno, Mazzorno Sinistro and Cavanella Po, where the branch starts from Po di Levante, which passes in front of Porto Viro (14,591 inhab. in 2014). It follows the main course through Taglio di Po (8,351 inhab. in 2014) and the twin Contarina, across the river, past Ca' Capellino, Veniero and Villareggia (1015 inhab. in 2010), located in front of the mouth of the Po della Donzella branch. The Po continues through Porto Tolle (9920 inhabitants in 2014), Tolle and Ca' Dolfin, just before it empties into the Adriatic Sea.

In summary, the Po crosses (from the source to the mouth) 13 provinces: Cuneo, Turin, Vercelli and Alessandria (Piedmont region), Pavia, Lodi, Cremona and Mantua (Lombardy region), Piacenza, Parma, Reggio Emilia and Ferrara (Emilia-Romagna region) and Rovigo (Veneto region). There are 183 riverside municipalities (that touch the banks of the river) belonging to the aforementioned 13 provinces bathed by the Po.

Main tributaries of the Po

The Po officially has 141 tributaries, of which the most important, by length, basin or flow, are the following.

Left tributaries

- Pellice, abundant torrent of 60 km in length, which with its tributary the Chisone, leads to the Po an average 22.3 m3/s;

- Sangone, torrent of some 47 km which flows into the Po between Turin and Moncalieri;

- Dora Riparia, derives its name from one of its sources: the Ripa. From its origin, which is between the three steps of the Monginevro, Colle del Frejus and Moncenisio, descends through the Valley of Susa and flows into the Po, in Turin, with an average flow of 26 m3/s;

- Stura di Lanzo, which originates a little south of the Great Paradiso of the union of the branches of the ViùOf the Ala and Valgrande and that, after 65 km of course, enters the Po with a covetous medium flow 32 m3/s;

- Orco, another river in the area of Turin that is born in Gran Paradiso and after some 100 km of course in the Po in Chivasso providing an average of 24 m3/s;

- Dora Baltea, an important river that flows from Mont Blanc and is richly fed by the extensive glaciers of Monte Rosa, Cervino and Gran Paradiso. It takes its name from the Balteo, which descends from the side valley of the Col of the Small San Bernardo, runs through the Valle d'Aosta and enters the plain near Ivrea. Al Po pours half, after 160 km course draining a basin 4322 km2Ones. 110 m3/smaking it the fifth inflow by average annual flow;

- Sesia, coming from Mount Rosa and running through a valley (the Valsesia) is not very important in terms of transport since it does not lead to any step by road. In the sand banks that leave at their pace, there are traces of gold. Baña the city of Vercelli and pour into the Po to 10 km downstream of Casale Monferrato after 138 km course with an average flow of more than 70 m3/s;

- Agogna, born from Mottarone, crosses the province of Novara, the province of Pavia and dewaters in the Po after 140 km with an average flow rate 13 m3/s;

- Ticino river, which is born in the San Gottardo region and runs to Biasca in a very narrow valley (Val Leventina), flanked by high mountains covered with permanent snow and glaciers. In Biasca the valley opens and the river, after crossing the capital of Ticinesa Bellinzona, descends to Lake Maggiore, where Lake Toce (Val d'Ossola) flows. So far the course of the Ticino belongs to the Swiss territory (Canton Ticino). Lake Maggiore interrupts its course about seventy kilometers; after having left the lake in Sesto Calende, the river, enriched by the contribution of many important tributaries that flow directly into the lake (Toce, Verzasca, Maggia, Tresa, etc.), continues, marking the border between the Piedmont and Lombardy for a hundred kilometers to the Po, with which it converges shortly after. Its course is navigable for discreet tonnage ships. Both on the right and on the left are important navigation and irrigation channels: Canal Cavour, Naviglio Grande, el Villoresi. Also along its shores can trace the gold sands. Although it is only the longest affluent room in the Po (248 km) is, with much, the 1.o by average annual flow (350 m3/s) and, especially at the end of spring (515 m3/s in June, which amounts to more than half of the Po Flow that month), occupying the second absolute place of Italy by Flow, after the same Po;

- Southern Olona, sometimes also known as the lower Olona to distinguish it from the homonymous river — which is born in the province of Varese— is born near Bornasco in the province of Pavia and conflues with the Po near San Zenone al Po. The Olona has 40 km and drain a watershed 130 km2;

- Lambro, a modest river from the Triangolo Lariano, which crosses the Brianza and borders Milan. It flows into the Po in Orio Litta with an average flow rate 12 m3/s. The Lambro, also called North Lambro, has 130 km, and its main tributary is the corresponding Southern Lambro of very poor quality water;

- Adda River, the largest tributary of the Po by length (313 km) and the second by medium flow in the mouth (almost 190 m3/s); its various sources arise from the yoke of the Stelvio and the Gruppo de los Ortles. It flows into the lake of As, in the Valtellina; this divides the rhetic Alps of the orobic Alps, it is flat and fertile, rich and populous; the most important centers are: Bormio, Tirano and Sondrio. In Lecco, the river takes its course to the Po; it addresses it in the section between Piacenza and Cremona, after having received the contribution of two rivers of bergamascos: the Brembo and the Serio, which descend from the Alps Orobiche (Pico del Diavolo and pico Coca);

- Oglio, fed from the waters that come from Cevedale, Adamello-Presanella and Presolana, runs impetuous and fast 80 km to the lake of Iseo (or Sebino) in a valley in the most narrow part: the Valcamonica. After the lake, he describes an arch and then goes parallel to the Adda and Mincio, towards the Po. The most important tributary is the Chiese, who descends from Adamello on the left of the Oglio, through the middle section of the Giudicarie. With her 280 km course is the 2.o affluent of the Po by length, but it is the 3.o by medium flow in the mouth (137 m3/s);

- Sarca-Mincio, from the eastern side of the Adamello with the name of Sarca, is fed by the water of the Dolomites of Brenta entering near Riva in the lake of Garda and coming out near Peschiera with the name of Mintius markedly enriched. It plays the city of Mantua after carving the cord of the Morrenic hills of Solferino and San Martino, battle theatre of the Second War of Independence. The Sarca-Mincio system 203 km long, it constitutes the tributary of the Po of greater regularity of flow, because of the fundamental calmer action of Lake Garda: the medium module is about 60 m3/swith a minimum flow that never falls below 35 m3/swhile the maximum rarely exceeds 150 m3/sbecause downstream of the lake there are virtually no tributaries.

Right tributaries

- Tanaro, with much, the greater by length (276 km), drained surface (8324 km2after the Arno and medium flow in the mouth (131.76 m3/s) of its affluents on the right. By average volume of water is also the 4.o of all tributaries, after Ticino, Adda and Oglio. It is born on Mount Saccarello, in the Ligurian Alps. At first it seems to be directed regularly to Turin to lead in the Po, but quite close to Cherasco it turns towards the east, marking the natural border between the Langhe and the Roero, where it opens a huge gap through the Morrenic hills of the Monferrato, after which it is directed towards Asti, Alessandria and the confluence with the Po. It receives on the right the Bormida and, on the left, the Stura di Demonte: the first descends from the Alps ligures and the Apeninos Ligures, and the second from Argentera (col de la Maddalena).

- Scrivia, born in the Apennines Ligures, in mount Genoa, runs in the narrow valley of the same name to Serravalle, where it flows into the plain with an average flow of 23 m3/s. Throughout its course, the great communication route that goes from Turin and Milan, through Passo dei Giovi, descends to Genoa.

- Trebbia, born in the Prelà Mountain (1406m. n. m.) in the Apeninos Ligures and communicates the Pyacentino territory with the genoves, through Bobbio. It runs in a narrow valley, deep and largely wild; it receives the Aveto that provides half of the flow, cuts the Emilia road near Piacenza, where it falls in the Po. After the Tanaro, the Secchia and the Taro is the 4th affluent of the right by medium flow in the mouth, with almost 40 m3/sdespite its relatively short course (115 km).

- River Taro, born on Mount Penna (waters above Rapallo). It flows shortly after Fornovo, on the Padana plain after receiving the Ceno, with a very long alveo (almost of 2 km), cut the Emilia road just before Parma and flows into the Po near Gramignazzo. It's 3.♪ right affluent by medium flow in the mouth (approximately 41 m3/s), and the 4.o by length (126 km).

- Torrente Parma, born from Lake Santo parmense and the Gemio and Scuro lagoons located on the ridge in the Orsaro and Sillara mountains. The two branches converge upstream of the town of Bosco to give origin to the Parma torrent propriomente dicho. The river receives many tributaries, including the torrent Baganza, in the city of Parma. After a tour of some 100 km joins the Po in the town of Mezzano Superiore providing an average 11,3 m3/s.

- Enza, born in Passo del Lagastrello, just east of the Alps di Succiso, receives Cedra, flows into the plain in San Polo d'Enza and flows into the Po in Brescello, in front of the Viadana lombard after 93 km course with an average contribution of around 12 m3/s.

- Secchia, born near the apennic valley of the Cerreto and flows into the Po, just downstream from the point where the Mint converges, on the opposite shore, after 172 km of course, being the second right affluent by length and flow (42 m3/s).

- Panaro, descends from the Passo del Giovo del Monte Rondinaio and collects a wide variety of tributaries from the highest section of the northern Apennines. After having flown into the emilian plain to the southeast of Modena, near Vignola, converges in the Po to the west of Ferrara resulting, with its 148 km course and average flow 37 m3/s respectively, the third right affluent by length and the fifth by volume of water.

The Po Valley

The vast valley around the Po is called the Po Basin or Po Valley (Italian: Pianura Padana or Val Padana); over time it became the main industrial zone of the country. In 2002, more than 16 million people lived in it, at that time almost ⅓ of the total population of Italy.

The two main economic uses of the valley are industry and agriculture. Industrial centers, such as Turin and Milan, are on higher ground, away from the river. They rely on power from the many hydroelectric power plants in, or on the flanks of, the Alps, and on coal/oil-fired power plants that use water from the Po Basin as a coolant. The drainage of the northern slope of the valley is mediated by several large lakes, with a strong landscape character. The flows are controlled by so many dams that they slow down the sedimentation rate of the river, causing geological problems. The expansive wet and fertile floodplain is reserved primarily for agriculture and is subject to seasonal flooding, despite the fact that the total amount of water is less than in the past and below demand. The main products of the farms around the river are cereals, including—unusually for Europe—rice, which requires heavy irrigation. These cereal uses are the main consumer of surface water, while industrial and human consumption make use of groundwater.

The Po delta

The active delta

The most recent part of the delta, which projects into the Adriatic between Chioggia and Comacchio, has channels that actually connect to the Adriatic Sea and is therefore called the active delta by the park authorities (compared to the fossil delta, that has channels that no longer connect with the sea but that did before). The active delta was created in 1604 when the Republic of Venice diverted the main stream, the Po grande or Po di Venezia, from its channel north of Porto Viro to the south from Porto Viro in a canal they called the Taglio di Porto Viro, (Porto Viro shortcut). His intention was to stop the gradual migration of the Po into the Venetian Lagoon, which could have silted it up. The subsequent town of Taglio di Po grew around the diversion works. The Volta Grimana lock blocks the former canal, now the Po di Levante, which flows into the Adriatic through Porto Levante.

Following the Taglio di Po, the Parco Regionale Veneto, one of the stretches under the authority of the Parco Delta del Po, has the last branches of the Po: the Po di Gnocca, to the south, followed by the Po di Maestra, to the north at Porto Tolle. In Tolle, the Po di Venezia continues downstream, dividing into the Po delle Tolle, to the south, and the Po della Pila, to the north. The first one comes out through Bonelli. And the latter divides again in Pila into the Busa di Tramontana, to the north, and the Busa di Scirocco, to the south, while the main stream, the Busa Dritta, it enters Punta Maistra and finally leaves past the Pila lighthouse.

Although the park administration states that the active delta begins at Porto Viro, there is another active channel upstream at Santa Maria in Punta, where the Po river divides into the Po di Goro and the Po di Venezia.

The Fossil Delta

The Fossil Po is the region of now-inactive channels that led from the Po to the sea. It starts upstream from Ferrara. The Po currently flows north of Ferrara and is actually the result of a diversion at Ficarolo made in 1152 in the hope of alleviating flooding in the vicinity of Ravenna. The diversion channel was originally called Po di Ficarolo. The Po river, until then, followed the Po di Volano, which since then is no longer connected to the Po, which runs south of Ferrara and exits near Volano. In Roman times it did not come out there, but ran south as the Padus Vetus ("old Po") leaving near Comacchio, from where the Po di Primaro started leaving near Ravenna.

Before 1152 the seaward extension of the current delta was non-existent for about 12 km. The entire region from Ravenna to Chioggia was dense swamp, which explains why the Via Emilia was built between Rimini and Piacenza and did not start further north.

Protected areas in the delta

The wetlands of the Po delta have been protected with the institution of two regional parks in Veneto and Emilia-Romagna. Emilia-Romagna's Delta del Po Regional Park, the largest, consists of four parcels of land on the right bank of the Po and to the south. Created by law in 1988, it is administered by the Consorzio per la gestione de Parco, to which the provinces of Ferrara and Ravenna belong, as well as nine communes: Comacchio, Argenta, Ostellato, Goro, Mesola, Codigoro, Ravenna, Alfonsine and Cervia. The executive power resides in an assembly of the presidents of the provinces, the mayors of the communes and the administration council. They employ a Technical-Scientific Committee and a Park Council to carry out the directives. In 1999 the park was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site and was added to "Ferrara, a Renaissance city, and its Po delta". The 53,653 ha of the park contain wetlands, forest, dunes and salt flats. It has a high biodiversity, with 1,000-1,100 plant species and 374 vertebrate species, of which 300 are birds.

Protected areas in the delta del Po |

|---|

|

Cities and towns along the Po

Along the Po are many cities and towns. The most prominent are listed in the table below, highlighting in bold those with more than (20,000 inhabitants) (in parentheses, the provincial code is included).

Locations on the banks of the Po River |

|---|

|

Protected areas in the Po basin

There are many areas in the Po basin that enjoy some kind of protection. They are collected in the table that follows.

Protected areas in the Po basin |

|---|

|

Water regime

The catchment area of the Po (reaching about 71,000 km²) covers much of the southern slopes of the Alps and the northern slopes of the Apennines Ligures and Tusco-Emilians. For this reason, it has a mixed fluvial regime of the Alpine type (floods in late spring and summer and summer in winter) and Apennine (floods in spring and autumn and summer summer), but the Apennine regime prevails in any case, since that, despite the summer feeding of alpine glaciers, the minimum flow is experienced during the summer (usually in August), a phenomenon accentuated in recent decades by the progressive reduction of alpine glaciers.

Floods from the river, usually concentrated in the fall due to rainfall, are quite frequent and can be impressive and devastating as they have been several times in the last century. Mainly the Piedmontese tributaries (Dora Baltea, Sesia and Tanaro, in particular) and Lombards (Ticino) are determining factors in floods. To give some examples, during the flood in November 1994 the river already showed in Piedmont, after the confluence of the Tanaro, a flow of 11 000 m³/s, almost comparable with the one that travels much later downstream in the valley, in Polesine. The same thing also happened in October 2000, again in Piedmont, where the river already passed in the commune of Valenza with 10 000 m³/s of maximum flow, mainly because of the strong contributions of Dora Baltea and Sesia.

The absolute maximum values of Po flow were achieved during the 1951 and 2000 floods, with a peak of more than 13,000 m³/s in the medium-low course.

Average monthly flow

| Average monthly flow of the Po at the station of Pontelagoscuro |

|

Floods and Floods

The first flood caused by the Po for which there is reliable information dates back to 204 BC. C. as reported by Tito Livio. Since then 138 events have been known (an average of approximately one extraordinary flood every 16 years). The most important were:

- 589: Rotta della Cucca. Growing up that meant a substantial change in the hydrography of the véneto-padana plain.

- 1152: Rotta di Ficarolo. Inundation in Polesine with the birth of Po di Venezia. The Po remained diverted for about 20 years.

- 1330: Inundation of Polesine and Mantovano. 10 000 deceased.

- 1705: Inundación en el Modenese, Ferrarese y Mantovano con la muerte de 15.000 personas.

- 1839: Rotta in Bonizzo and the consequent flooding of the Mirandolano. The village of Noceto, between Caselle Landi and San Rocco al Porto, was completely destroyed by water.

In the XX century the most important floods were:

- May and June 1917: two floods with the full participation of the Po (25 May and 4 June). The second of which exceeded in the Polesella hydrometer the previous known maximum value of 1872 (8.17 m, at 7.46 m from the previous record). The river remained above the level of danger for more than 40 days. It had broken in Meleti, Castelnuovo Bocca d'Adda and Mortizza, near the confluence with the Adda. In Pontelagoscuro a maximum flow rate was measured 8900 m3/s.

- November 1951: This was the worst flood of the century. The Po broke in Occhiobello flooding 113,000 hectares of land and causing 89 deaths. In Pontelagoscuro the maximum flow reached 10 300 m3/s, historical maximum since the beginning of the measurements in 1807.

- November 1994: strong and continuous rains that affected the Pyamontes and Lombard tributaries. The rotates and the resulting floods occurred downstream from the confluence of the Orco and the Dora Baltea, hitting in particular, Chivasso, Trino, Crescentino, Morano sul Po and, below, Ghiarole. There were 70 victims. In Pontelagoscuro a maximum of 8700 m3/s.

- October 2000: this is the second largest increase in the maximum capacity of the centuryXX.: in Pontelagoscuro actually recorded a peak of 9600 m3/s, while at Ponte Becca the flow was 13 220 m3/s. There were floods in Piedmont, Lombardy and Emilia-Romaña. There were 23 victims, 11 disappeared and 40,000 displaced persons.

Note: the flow in Pontelagoscuro has often suffered dam breaks upstream, so there is no incompatibility with higher flows measured in upstream sectors.

Geology

The Mediterranean basin is a depression in the Earth's crust caused by the sliding of the African plate under the Eurasian plate. As usual in the geological history of the depression, it was filled with seawater, a sea known by various geological names, such as the Tethys Sea. In the last period of the Miocene, the Messinian (between 5 and 7 my ago), the Messinian salt crisis, almost the drying up of the Mediterranean, caused by the drop in sea level below the threshold of the Strait of Gibraltar and by the imbalance between evaporation and replacement, favored evaporation. At that time, the Po valley and the Adriatic depression constituted a single system of a canyon hundreds of meters deep. In the southwest, the Apennine Mountains border a landmass geologically named Tyrrhenis. Its orogeny was only completed in the Miocene. In the north, the Alpine orogeny had already created the Alps.

At the end of the Messinian the ocean broke through the sill and the Mediterranean refilled. The Adriatic transgressed all of northern Italy. In the later Pliocene sedimentary discharges, mainly from the Apennines, filled the valley and the central Adriatic in general, to a depth of 1000−2000 m, but between 2000−3000 m opposite the current mouth of the Po, with peaks as high as 6000 m. At the beginning of the Pleistocene the valley was full. The cycles of transgression and regression are detectable as far as the central part of the Po Valley and in the southern Adriatic Sea.

The alternation of Pleistocene marine and alluvial sediments occurred as far west as Piacenza. The exact sequences have been studied in detail in several places. The sea appears to have moved up and down the valley in accordance with a balance between sedimentation and the advance or recession of glaciers, at intervals of 100,000 years and with sea level fluctuations of 100−120 m. It began an advance after the last glacial maximum around 20,000 years ago, which meant that the Adriatic was at a high point about 5500 years.

Since then, the Po delta has been prograding. The progradation rate of the coastal zone between 1000 B.C. C. and 1200 AD. C. was 4 m/yr. Some human factors, however, brought about a change in the equilibrium in the middle of the XX century. , causing the entire northern Adriatic coast to be now degrading. Venice, which was originally built on offshore islands, is most at risk from subsidence, but the effect affects the Po delta as well. The causes are, first of all, a decrease in sedimentation velocity due to the blocking of sediments behind hydroelectric dams and the deliberate excavation of sand from riverbeds for industrial purposes. Second, the agricultural use of the river is intense; During consumption peaks, the flow in some places leaves the channel dry, causing local containment. As a result of decreased flow, saltwater is introduced into aquifers and coastal groundwater. Eutrophication from standing waters and low-flow streams are increasing. The valley is subsiding due to the removal of groundwater.

Fish fauna

The Po and its tributaries have an original fish fauna of the highest biogeographical and ecological interest, with a very high rate of endemism. Unfortunately, in the second half of the XX century, many alien species have been introduced, contaminating this extraordinary biodiversity, which has led to to the depletion of many endemic species and has threatened some with extinction. Some endemic or sub-endemic species in the Po Valley are listed below:

The following is a partial list of some of the more widespread alien species:

- Abramis brama - Brema

- Ameiurus melas - Pez cat

- Aspius aspius - Aspio

- Barbus Barbus - Barbo danubiano

- Blicca bjoerkna - Blicca o brema blanca

- Carassius auratus - Carassio

- Ctenopharyngodon idella - Herbivorous tent or Amur

- Gambusia affinis - Gambusia

- Gymnocephalus cernuus - Acerina

- Hypophthalmichthys molitrix - Carpa testa grossa o Temolo russo

- Ictalurus punctatus - Pez cat maculato

- Lepomis gibbosus - Perca sol

- Micropterus salmoids - Perca atruchada

- Oncorhynchus mykiss - Risted trout

- Pseudorasbora parva - Pseudorasbora o Cebacek

- Rhodeus sericeus - Rodeo

- Rutilus rutilus - Gardon

- Sander lucioperca - Lucioperca or Sandra

- Silurus glanis - Siluro

On August 23, 2006, a Papuan loggerhead turtle (Carettochelys insculpta) was captured in the Po river, in the province of Ferrara. a snapping turtle (Chelydra serpentina) was found.

In August 2009, a piranha of the species Pygocentrus nattereri was captured in the river.

Ecological impacts

Numerous native and endemic fish species are threatened by various causes, one of the most important being the presence of non-native species: some of these species (especially catfish, but also asp, walleye, and catfish) are extremely damaging as predators, while others (such as bream, blicca, gardon or roach, rodeo, etc.) harm local fauna as competitors. To these can be added the Louisiana red crab (Procambarus clarkii), which is also capable of having a significant impact on fish stocks, the environment and waterworks. Other threats include pollution and the construction of dams without fish lifts, such as the Casale Monferrato dam, which prevent migratory species such as common sturgeon, cobic sturgeon and shad from being able to go up the river to spawn.

In 2022, the river's water level was very low and restrictions on water consumption have been imposed in many municipalities in the region.

Human aspects

Navigation on the Po

At one time the Po was the most important channel of communication between the Adriatic Sea and the northwest of the country. Since ancient times it has been incorporated into the heart of Lombardy, transporting people and goods. Over time, the traffic intensified, also involving the Ticino, Mincio, Adda rivers and the entire network of artificial canals built between the Middle Ages and today.

The river was traversed in both directions by increasingly numerous and significant vessels. The descent was, in many cases, problematic and to maintain the route, it was common in most cases to use oars and a chain drag rudder on the bottom of the river. To go up the river, in addition to sails, teams of horses, donkeys, oxen and even men were used. The boatman also used a long stick to push himself, walking the boat from front to back.

The different types of boats (bucentauro, barge, rascone, magàne, barbotte, burchi) varied in size, but they all had a raised bow and a flat bottom that allowed them to navigate in areas with high depths.

Today, the Po is navigable for about 389 kilometers from the mouth of the Ticino to the sea. There are active commercial shipping services from Cremona to the sea (292 km).

Pollution

Always prone to fog, the valley is subject to heavy smog due to industrial air emissions, especially from Turin

In 2002, the city of Milan did not have any wastewater treatment plants. The wastewater was being dumped through canals directly into the Po, so the European Environment Agency warned the city. Since 2005, all Milan's wastewater is treated at three different plants in Nosedo, San Rocco and Peschiera Borromean. The three plants can collectively treat the equivalent wastewater of more than 2.5 million inhabitants.

In 2005, the waters of the Po were found to contain amounts of benzoylecgonine, which was excreted in the urine by cocaine users. Based on these figures, cocaine use was estimated at around 4 kg per day, or 27 doses per day for every 1,000 young adults in the areas that feed into the river, a number almost three times higher than previous estimates.

On February 24, 2010, the Po was contaminated by an oil spill from a refinery in Villasanta via Lambro, the Agenzia Nazionale Stampa Associata estimating that the spill had been about 600,000 liters.

Management of water sources

Until 1989, water resources were managed at the regional or local level. The main authority in Lower Po was the Magistrato alle Acque di Venezia, having been an office instituted in the century. XVI in the Republic of Venice. He made all the decisions regarding the diversion of the lower river. Most of the delta is still in the Veneto.

In 1907 under the Kingdom of Italy, the agency became Magistrato alle Acque and took charge of all water resources in northeastern Italy. At present it is a decentralized institution of the Ministry of Public Works, directed by a president appointed by the head of State and the Council of Ministers. Its headquarters are in Venice. His domain is the management and protection of the water system in Veneto, Mantua, Trento, Bolzano and Friul-Venezia Giulia.

In 1989, in response to the main geological problems detected along the river, Law no. 183/89 was passed authorizing the Po River Basin Authority (Autorità di bacino del fiume Po), who directed operations related to water resources in the Po Basin (see Po Valley below). Its headquarters have been in Parma since its creation in 1990. It considers itself a synergy between all the institutions dealing with the conservation and development of the Po basin. It is administered by officials elected from among the administrations of the constituent regions and provinces.

In 2009, the Basin Authority initiated an integrated basin management plan in accordance with the European Union (EU) Water Framework Directive 2000/60/EC. The plan includes many of the water management and flood risk plans that were already approved. The Po Valley Project (the implementation of the plan) contemplated carrying out between 2009 and 2015 more than 60 measures to raise and strengthen the dikes, increase the natural retention zones, recover the transport of sediments, recover the hydromorphological characteristics, expand wetlands, afforest, restore the natural state, promote biodiversity and promote recreational use, among others.

Dams

In the village of Isola Serafini in the municipality of Monticelli d'Ongina, Province of Piacenza, 40 km downstream of Piacenza, a dam of 362 m long crosses the Po, with a 20 m lock with eleven, of 30 m, openings closed by vertical lift locks. Nine gates are 6.5m high and two are 8m to limit the sediments. A spillway to the right passes through a hydroelectric station with four 76 MW generators each operated by a 3.5 m - 11m. The spillway connects to a diversion channel that subtends the 12 km loop of the Po. A ship lock 85 m long and 12 m wide, next to the station, allows some traffic to pass through the canal, but above the dam the traffic is mainly barges. The average flow in the dam is 854 m³/s, with a maximum of 12,800 m³/s.

Bridges over the Po

The Po River System

The main tributaries of the Po (it has a total of 141) are listed in the table below. The tributaries are ordered geographically, following the river from its source to the mouth, and the direction in which the tributaries flow, left-right, are also considered downstream.