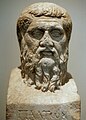

Plato

Plato (Ancient Greek: Πλάτων, Plátōn ; Athens or Aegina, c . 427-347 BC) was a Greek philosopher, follower of Socrates, and teacher of Aristotle . C. he founded the Academy of Athens, an institution that would continue for more than nine hundred years and to which Aristotle would go from Stagira to study philosophy around 367 BC. C., sharing about twenty years of friendship and work with his teacher .

He actively participated in the teaching of the Academy. He wrote his works, mostly in the form of dialogue, on the most diverse topics, such as: political philosophy, ethics, psychology, philosophical anthropology, epistemology, epistemology, metaphysics, cosmogony, cosmology, philosophy of language and philosophy of education. Unlike his contemporaries, all of his work is believed to have survived intact .

Plato developed his philosophical doctrines through myths and allegories. In his "theory of forms" or "ideas", he maintained that the sensible world is only a "shadow" of a more real, perfect and immutable one from which the universal concepts that structure reality come from the "Idea of Good". "; and the human soul, which is immortal but is "imprisoned" in the body. According to his "reminiscence theory", ideas are innate in the soul and "remembered" by reason ( anamnesis). Plato is also considered one of the founders of political philosophy, considering that the just city would be governed by "philosopher kings". He also tried to translate his original political theory into a real State, which is why he traveled twice to Syracuse, Sicily, with the intention of putting his project into practice there, but he failed both times and managed to escape painfully and risking his life due to the persecutions he suffered from his opponents. From Plato we also receive the concepts of "platonic love" and "platonic solids".

Plato died at the age of 80, spending the last years of his life teaching at the Academy in his hometown. After his death, this institution was in charge of his nephew Speusippus. For several centuries, the "Old Academy" was abandoning Platonism, taking a philosophical turn towards skepticism in the "New Academy". This was permanently closed by Emperor Justinian in 529 .

In the 1st century BC. C., Antiochus of Ascalon took up Plato's ideas absorbing doctrines from the Peripatetic and Stoic school, thus forming the so-called "middle Platonism" followed by Philo of Alexandria and Plutarch. This was in turn the basis of the so-called "Neoplatonism", defended by philosophers such as Plotinus and Porphyry. These doctrines influenced Christian, Jewish and Islamic religions during the Middle and Modern Ages in figures such as Saint Augustine, Avicenna, Maimonides, Marsilio Ficino, Henry More, and Georg Wilhelm Hegel. Platonism was later criticized by philosophers such as Nietzsche, Heidegger, and Popper.However, his influence as an author and systematizer has been incalculable in the history of philosophy, which has often been said to have achieved identity as a discipline thanks to his work. Of him, Alfred North Whitehead commented:The surest general characterization of the European philosophical tradition is that it consists of a series of footnotes to Plato.Alfred North Whitehead (1929 )

Biography

Birth and family

Plato was born around the year 427 BC. C. in Athens or on the island of Aegina, within an Athenian aristocratic family. He was the son of Ariston, who claimed descent from Codrus, the last of the kings of Athens, and Perictione, whose family was related to Solon. He was the younger brother of Glaucon and Adeimantus, older brother of Potone (mother of Speusippus, his future disciple and successor in the direction of the Academy) and half-brother of Antiphon (since Perictione, after the death of Aristo, married Pirilampes and had a fifth child). Critias and Charmides, members of the oligarchic dictatorship of the Thirty Tyrants, who usurped power in Athens after the Peloponnesian War, were Plato's uncle and cousin on his mother's side, respectively.In keeping with his background, Plato was a staunch anti-democrat (see his political writings: Republic , Politician , Laws ); However, this did not prevent him from rejecting the violent actions that had been committed by his oligarchic relatives and refusing to participate in his government .

Name

Plato's name was, apparently, the nickname given to him by his gym teacher and which translates as one with broad shoulders , according to Diogenes Laertius in Life of Illustrious Philosophers . His real name was Aristocles .

Education

Speusippus, Plato's nephew, praises the quickness of mind and modesty he had as a child, as well as his love of study. In his youth he would have been interested in arts such as painting, poetry and drama; in fact, a set of epigrams is preserved that are usually accepted as authentic, and tradition reports that he had written or was interested in writing tragedies, an effort that he would have abandoned when he began to frequent Socrates, —note the harsh criticism that Plato makes of the arts in Republic—, justifying his partial expulsion from the ideal State. Also, as seen in his educational theory, he was always interested in gymnastics and body exercises, and certain sources refer that he would have devoted himself to athletic practices; he would also have participated in some battles of the Peloponnesian War and the Corinthian War, but there is no information about it other than simple mentions of the case .

Regarding his early intellectual formation, Aristotle refers that, before meeting Socrates, Plato had dealt with the Heraclitean Cratylus and his ideas that everything sensible is in the process of becoming and, therefore, that scientific knowledge about it is not possible. of it; but that later, influenced by Socrates and his teaching and insistence on inquiring and defining what each thing is in order to be able to speak of it properly, he became convinced that there were knowable realities and, therefore, permanent, and decided that they were not sensible —the realm of what always becomes and never is—but of intelligible nature. This is, according to Aristotle, the origin of the theory of Ideas, and his information allows us to reconstruct something of Plato's biographical-intellectual itinerary .

According to Diogenes Laertius, Plato met Socrates at the age of 20, although the historian WKC Guthrie is convinced that he had frequented him before then. In any case, it can be agreed that the first meeting took place between 412 and 407 (that is, between Plato's fifteen and twenty years). From then on, he was one of the closest members of the Socratic circle until in 399, Socrates, who was about seventy years old, was sentenced to death by the Athenian popular court, accused by the citizens Anito and Meletus of " impiety" (i.e. disbelieving in or offending the gods) and "corrupting the youth". The Apologyit shows us Socrates in front of the court, rehearsing his defense and accusing his opponents of the injustice they were committing against him; after being found guilty, Socrates mentions a group of friends who are in the gallery, including Plato. However, Plato himself makes Phaedo say, in the dialogue that bears his name and when referring to Echecrates on the last evening of Socrates with his friends before drinking the hemlock, that "Plato was sick, I think". In his absence, W. K. C.He writes: "To judge him unfavorably for this would be unfair, since not only do we owe this circumstance to Plato himself, but the whole of the Phaedo, to say nothing of the other dialogues, leaves beyond doubt the undoubted reality and force of his devotion to Socrates. His feelings may have been so intense that he could not bear the spectacle of witnessing the actual death of the best, the wisest, and the most just of men he knew."

After the loss of Socrates, Plato, who was only twenty-eight years old, retired with some other of his teacher's disciples to Megara, Sicily, to the house of Euclid (Socratic, founder of the Megaric school). From there he would have traveled to Cyrene, where he met the mathematician Theodore (personified in the Theaetetus) and Arisitippus (also a Socratic, founder of the Cyrenaic school) and to Egypt, although these last two trips are doubted by many specialists. .On the other hand, the trips to Italy and Sicily are considered safer, not only because there are more testimonies, but also because of the decisive Letter VII, on the basis of which the rest of his voyages are reconstructed. On his trip to Italy he would have had contact with the Eleatians and Pythagoreans, two of the main influences that accuse his works, especially with Philolaus, Euritus and Archytas of Tarentum, who was, at the same time, a politician and a philosopher in his polis .. In 387 BC C. he traveled for the first time to Sicily, to the powerful city of Syracuse, ruled by the tyrant Dionysus; there he met Dion, the brother-in-law of Dionysus, to whom he was strongly attracted and to whom he transmitted the Socratic doctrines of virtue and pleasure. According to a traditional account, at the end of his visit, Plato would have been sold into slavery by order of Dionysius and ransomed by the Cyrenaic Anniceris at Aegina, a polis that was at war with Athens .

Academy and old age

On his way back from Sicily, it is estimated that shortly after, Plato bought a farm on the outskirts of Athens, on a site dedicated to the hero Academus, and founded the Academy there, which functioned as such uninterruptedly until 86 BC when it was destroyed. by the Romans, being restored and continued by the Platonists until in 529 AD it was definitively closed by Justinian I, who saw in the pagan schools a threat to Christianity and ordered their complete eradication. Numerous philosophers were trained in this thousand-year-old Academy , including Aristotle himself during the direction of Plato, with whom he worked for about twenty years, until the death of his teacher. It is worth recalling a certain description of W. K. C.Regarding the Academy: "... It is nothing like any modern institution (...) The closest parallels are probably our ancient universities (...) with the characteristics they have inherited from the medieval world, in particular their religious connections and the ideal of life in common (...) The sanctity of the place was great, and other cults were celebrated there, including those of Athena herself. In order to form a society that would have its own land and premises, as Plato did, it seems that it was a legal requirement to register it as a thíasos, that is, as a cult association dedicated to the service of some divinity. Plato chose the Muses, who exercised the patronage of education (...) The meals in common were famous for their combination of healthy and moderate food with a conversation that was worth remembering and writing down. A guest is reported to have said that those who had dined with Plato felt well the next day. At the Academy, which did not accept people without previous mathematical knowledge, teachings were given on different sciences (arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, harmony, perhaps also natural sciences) as a preparation for dialectics, the method of the philosophical inquisition, the main activity of the institution; Likewise, the main activity, in line with what was expressed in the Republic, was also the training of philosophers in politics, so that they were capable of legislating, advising and even governing (it is known of several Platonists who, after studying at the Academy, actually engaged in these activities).

Plato was also influenced by other philosophers, such as Pythagoras, whose notions of numerical harmony and geomathematics are echoed in Plato's notion of Forms; also Anaxagoras, who taught Socrates and who affirmed that intelligence or reason penetrates or fills everything; and Parmenides, who argued about the unity of all things and who influenced Plato's concept of the soul.

Plato died in 347 B.C. C., at 80/81 years of age, dedicating himself in his last years of life to teaching at the academy of his hometown.

Influences

Pythagoras

Although Socrates influenced Plato directly as related in the dialogues, Pythagoras' influence on Plato, or in a broader sense, the Pythagoreans, such as Archytas, also seems to have been significant. Aristotle claimed that Plato's philosophy closely followed the teachings of the Pythagoreans, and Cicero repeats this claim. Pythagoras held that all things are numbers, and the cosmos proceeds from numerical principles. He introduced the concept of form as something other than matter, and that the physical world is an imitation of an eternal mathematical world .

Numenius of Apamea accepted both Pythagoras and Plato as the two authorities one should follow in philosophy, but considered Plato's authority to be subordinate to that of Pythagoras, whom he regarded as the source of all true philosophy, including Plato's own. .

Heraclitus and Parmenides

The two philosophers Heraclitus and Parmenides, following the path started by pre-Socratic Greek philosophers like Pythagoras, depart from mythology and start the metaphysical tradition that strongly influenced Plato and continues today .

The surviving fragments written by Heraclitus suggest the idea that all things continually change or become. His image of the river, with ever-changing waters, is well known. Plato received these ideas through Heraclitus' disciple Cratylus, who held the more radical view that continual change justifies skepticism because we cannot define something that is not permanent in nature .

Parmenides took an entirely opposite view, arguing for the idea of immutable Being and the view that change is an illusion and as such, qualifies him as the founder of metaphysics or ontology as a domain of inquiry distinct from theology.

These ideas about change and permanence, or becoming and being, influenced Plato in formulating his theory of forms.

Plato's most self-critical dialogue is called Parmenides , in which Parmenides and his student Zeno appear, who after Parmenides' denial of change vigorously argued with his paradoxes to deny the existence of motion. Plato 's Sophist dialogue includes an Eleatic follower of Parmenides. In the dialogue, Plato argues that motion and rest "are", against the followers of Parmenides who say that rest is but motion is not.

Socrates

Plato was one of Socrates' devoted young followers. The precise relationship between Plato and Socrates remains an area of discussion among scholars.

Aristotle attributes a different doctrine regarding forms to Plato and Socrates. Aristotle suggests that Socrates' idea of the Forms can be discovered through investigation of the natural world, unlike Plato's Forms which exist beyond and outside the ordinary range of human understanding. According to Letter VII, Plato he saw Socrates as "the most just of the men of his time" (324e). According to Diogenes Laertius, the respect between the two was mutual. Letter II , says "I have never written anything, and there is not and never will be." works by Plato; those attributed to me are by Socrates." However, the latter letter is considered to be a forgery .

Construction site

All of Plato's works, with the exception of the Letters and the Apology , are written—like most of the philosophical writings of the time—not as pedagogical poems or treatises, but in the form of dialogues; and even the Apology contains sporadic dialogue passages. In them Plato places a main figure, most of the time Socrates, who develops philosophical debates with different interlocutors, who through methods such as indirect comment, excursions or mythological story, as well as the conversation between them, relieve, they are completed or interwoven; Monologues of some length are also used.

Among the Platonic dialogues, which are stylistically characterized by sharing the form of dialogue, whose use in philosophy he inaugurated, the following can be pointed out as the most influential: Cratylus , an examination of the relationship between language and reality, evaluating both a theory naturalist of language as a conventionalist; Meno , an investigation of virtue as knowledge and its teachability, ontologically substantiated by a proof and exposition of the theory of reminiscence; Phaedo , a demonstration of the divine and imperishable nature of the soul and the first complete development of the theory of Ideas; The Banquet, the main exposition of the particular Platonic doctrine about love; The Republic , an extensive and elaborate dialogue in which, among other things, a political philosophy about the ideal state, a psychology or theory of the soul, a social psychology, is developed. a theory of education, an epistemology, and all this based, ultimately, on a systematic ontology; Phaedrus , in which a complex and influential psychological theory is developed and topics such as desire, love, madness are addressed , memory, the relationship between rhetoric and philosophy and the poverty of written language as opposed to genuine oral language; Theaetetus, an inquisition on knowledge in order to find its nature and its definition; Parmenides , a criticism of Plato - put in the lips of the Eleatic philosopher - to his own theory of Ideas as he had presented it until then and that would prepare the way for its reformulation in subsequent dialogues; Sophist , a work in which a restructuring of the eidetic world is developed and a presentation of the revolutionary theory about non-being as difference and the first finished foundation, from it, of the possibility is made. false judgment and opinion, as well as their difference from the corresponding true ones; Political, a dialogue that includes an exposition of the mature Platonic dialectical method, as well as the theory of the just measure, of the authentic politician and the authentic State, with respect to which the other models of political organization are presented as imitations; Timaeus , an influential essay of cosmogony, cosmology, physics and eschatology, influenced by the Pythagorean tradition; Philebo , research on the good life, on the relationship of good with good sense and pleasure as compounds of the former and enablers of living well and profitably ; laws, an extensive and mature theory about the proper constitution of the State, which opposes a greater realism to the pure idealism of the political philosophy presented in the Republic .

Plato also wrote Apology of Socrates , Crito , Euthyphro , Ion , Lysis , Charmides , Laches , Hippias Major , Hippias Minor , Protagoras , Gorgias , Menexenus , Euthydemus and Critias . There are several writings whose authenticity remains in doubt, and the dialogues Alcibiades I and Epinomis are the most important among them.The same happens with the surviving letters, although there is almost unanimity in accepting the genuine character of the important letter VII. Finally , we come to the question of the unwritten doctrines of Plato, whose oldest source is nothing more and nothing less than Aristotle, who mentions in several places theories that we do not find in the written work of his teacher .

Dialogue list

Plato was a very prolific author. His work was presented in the form of dialogue, putting into practice the principle of the Socratic dialectical method. The Greek philosopher's works have been arranged in many ways. One of the criteria has been according to his maturity stages. Calonge Ruiz and García Gual propose the following order :

Age of youth (393-389)

They are characterized by their ethical concerns. They are fully influenced by Socrates.

- Apology of Socrates (Speech of Socrates at his trial)

- Crito (Socrates in jail on civic problems)

- Laches (What is courage?)

- Lysis (What is friendship?)

- Charmides (What is temperance?)

- Euthyphro (What is Piety?)

- Ión (On poetry as a divine gift)

- Protagoras (On virtue and whether it is teachable)

Transition period (388-385)

This phase is also characterized by political issues, in addition, a first draft of the Reminiscence Theory appears and deals with the philosophy of language.

- Gorgias (On rhetoric, politics and justice)

- Cratylus (On the Meaning of Words)

- Hippias elder (What is beauty?)

- Hippias Minor (Is Voluntary Evil Better?)

- Euthydemus (On Eristic Sophism)

- Meno (On the Teaching of Virtue and Knowledge as Reminiscence)

- Menecene (Parody on funeral prayers)

Period of maturity (385-370)

Plato explicitly introduces the Theory of Ideas and develops in more detail that of Reminiscence. Likewise it is a about different myths.

- Phaedo (On the immortality of the soul, the last conversation of Socrates in prison)

- Banquet (About love. Myth of androgyne and the ladder of love)

- Republic (On politics and other matters: metaphysical, epistemological, etc. Allegory of the cave, the sun, the myth of metals, the rings of Gyges and Er)

- Phaedrus (On love, beauty and the destiny of the soul. Allegory of the winged chariot)

Age of old (369-347)

In this phase he revises his previous ideas and introduces topics about nature and medicine.

- Parmenides (Critique of the Theory of Ideas)

- Theaetetus (On Knowledge)

- Sophist (On language, rhetoric and knowledge)

- Political (On politics and philosophy)

Plato's growing pessimism, if we stick to the content of his last works, which already in the critical phase seemed to lean towards the predominance of mystical-religious and Pythagorean elements in his thought.

- Philebus (On Pleasure and the Good)

- Timaeus (Cosmology. Demiurge)

- Critias (Description of ancient Athens. Myth of Atlantis)

- The Laws (The ideal city, pessimistic review of the Republic)

- Letter VII (Plato presents a short autobiography)

The early dialogues show some resemblance to Socrates' style of inquiry. The dialogues of the medium developed a substantially metaphysical and ethical system to solve these problems. The central ideas are the World of Ideas, a theory that asserts that the mind is imbued with an innate capacity to understand and apply concepts in the world, and that these concepts are somehow more real, or more basically real, than the things of the world around us; the immortality of the soul, and the idea that it is much more important than the body; the idea that evil is a form of ignorance, that only knowledge can lead to virtue, that art should be subservient to moral purposes, and that society should be ruled by a class of philosopher kings.

In the later dialogues, Socrates figures less prominently, and the World of Ideas theory is called into question; More ethical direct questions become the focus. In the Republic, Plato attacks the political system of democracy, blaming it for the defeat of Athens in the Peloponnesian Wars. Plato attributes indecision to the masses (who voted on everything, including military strategies) as the reason for military defeat. Instead, he proposed a three-tiered hierarchical society, with workers, guardians, and philosophers, in ascending order of importance, citing the philosophers' great knowledge of ideas as the reason why they were suited to rule the world's society. moment.

Plato's works are currently arranged under the Stephanus pagination, which is used in modern editions and translations of his works (as well as those of Plutarch). Plato's works are divided into numbers, and each number is divided into sections of equal size according to the letters a, b, c, d and e. This system is often used to quote Plato.

Unwritten doctrines

For a long time, "Plato's Unwritten Doctrines" had been controversial. Many modern books on Plato seem to diminish his importance; however, the first important witness to mention its existence is Aristotle, who in his Physics writes: "It is true, indeed, that the account he gives there [i.e. in Timaeus ] of the participant is different from what he says in his so- called unwritten doctrine (ἄγραφα δόγματα)".It represents Plato's most fundamental metaphysical teaching, which he revealed only orally, and some say only to his most trusted companions, and which he may have kept secret from the public. The importance of the unwritten doctrines does not seem to have been seriously questioned before the nineteenth century. It is worth saying that the supporters of the unwritten doctrines make selective use of dialogues. Ultimately, Plato's substantive work is the dialogues, without which the unwritten doctrines would not exist .

One reason for not revealing it to all is partially discussed in the Phaedrus, where Plato criticizes the written transmission of knowledge as defective, favoring instead the spoken logos: "he who has knowledge of the just and the good and the beautiful ... will not , when seriously, write them in ink, seeding them through a pen with words, which cannot be defended with arguments and cannot effectively teach the truth." The same argument is repeated in the Seventh LetterPlato: "every serious man dealing with really serious subjects carefully avoids writing." In the same letter, he writes: "I can certainly declare about all these writers who claim to know the subjects I study seriously... there is not, nor will there be, any treatise of mine relating to it". Such secrecy is necessary so as not to "expose them to unseemly and degrading treatment" .

However, Plato is said to have once revealed this knowledge to the public in his discourse On the Good(Περὶ τἀγαθοῦ), in which the Good (τὸ ἀγαθόν) is identified with the One (the Unity, τὸ ἕν), the fundamental ontological principle. The content of this conference has been transmitted by various witnesses. Aristoxenus describes the event in the following words: "Each one came expecting to learn something about the things that are generally considered good for men, such as wealth, good health, physical strength, and in general a kind of wonderful happiness. But when came the mathematical proofs, including numbers, geometrical figures, and astronomy, and finally the statement The Good is One seemed to them, I imagine, completely unexpected and strange; hence some dismissed the matter, while others rejected it.Simplicio quotes Alexander of Aphrodisias, who states that "according to Plato, the first principles of everything, including the Forms themselves, are the Single and Indefinite Duality (ἡ ἀόριστος δυάς), which he called Great and Small (τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν )", and Simplicio also reports that "one could also learn this from Speusippus and Xenocrates and the others who were present at Plato's discourse On the Good ".

His account is in complete agreement with Aristotle's description of Plato's metaphysical doctrine. in metaphysics, writes: "Now, since the Forms are the causes of all else, he [i.e., Plato] supposed that their elements are the elements of all things. Consequently, the material principle is the Great and the Small [ i.e., the Dyad], and the essence is the One ( τὸ ἕν ), since the numbers are derived from the Great and the Small by participation in the One". "From this account it is clear that he only employed two causes: that of the essence and the material cause; for the Forms are the cause of the essence in all else, and the One is the cause of it in the Forms. He also us it says what is the material substratum from which the Forms are based in the case of sensible things, and the One in the case of Forms: that this is the duality (the Dyad, ἡ δυάς ), the Great and the Small ( τὸ μέγα καὶ τὸ μικρόν ).

"Middle Platonism" philosophers focused on synthesizing Plato's unwritten doctrines with the dialogue of the Timaeus . Inspired by Pythagoreanism, Plato made a metaphysical scheme with two opposing principles, the One and the Indefinite Dyad, the first being the one that imposes limits on the second, thus laying the foundations of the cosmos and generating the rest of the numbers, being the most important of these numbers the tetraktys .

Literary style

Use of dialogue

In the 4th century BC, the most important means of transmitting information was hearing, memorization, and orality, which outstripped writing. Plato was a prolific author, writing mainly in the form of dialogue, attempting to do so in the form " least written" possible. Through the "Myth of Theuth and Thamus" told by Socrates in the Phaedrus , he explains that the knowledge of writing is not embodied in the soul and the author cannot be asked questions, unlike dialogue. For Plato, thinking is a dialogue with the soul itself. By comparison, his disciple Aristotle held philosophical reading and writing in higher esteem, writing numerous treatises and instructing his students to encourage reading .

The characters in the dialogues are generally historical figures, such as Socrates, Parmenides of Elea, Gorgias and Phaedo of Elis, although sometimes some of whom there is no historical record apart from Platonic testimony also appear. In his early works, different characters discuss a topic by asking each other questions. Socrates figures as a prominent character, and that is why they are called "Socratic Dialogues". The dialogue-like structure allowed Plato to express unpopular opinions in the mouths of unsympathetic characters, such as Thrasymachus in the Republic . It should also be noted that while disciples of Socrates appear in many dialogues, Plato never appears as a character. He is only named in the Apology of Socrates and inPhaedo .

The nature of these dialogues changed substantially in the course of Plato's life. It is generally recognized that Plato's early works were based on the actual thoughts and conversations of Socrates, while his later works moved away from the ideas of his former master, being the work and ideas of Plato. In the later dialogues, which more either they have the form of treatises, Socrates is silent or absent, while in the immediately preceding ones he is the main figure and the interlocutors limit themselves to answering "yes", "of course" and "very true" .

UUUUUse of myth

The terms myths and logos underwent an evolution throughout the history of classical Greece. Thus, in the times of Homer and Hesiod (8th century BC) they were used as synonyms, with a meaning of narration or history . Later historians arrived, such as Herodotus and Thucydides, and also philosophers, such as Parmenides and the Presocratics, who introduced a differentiation between both terms, and thus myths became identified with an unverifiable narration , and logos with a rational narration .Plato being a disciple of Socrates and a strong supporter of logos-based philosophy, it would seem logical that he would have avoided the use of myths. He did however make great use of them. This fact has produced abundant analytical work, in order to clarify the causes and objectives of such use.

Plato distinguished between three types of myths. In the first place, there were false myths, such as those that related stories of gods subject to human passions and suffering, since reason teaches that God is perfect. Then he considered those myths that were based on true reasoning, and therefore true. Finally, there were the unverifiable myths because they were beyond the reach of human reason, but they contained some truth. Plato's myths have two types of content, on the one hand the origin of the universe, and on the other the morality and origin and destiny of the soul .

It is generally accepted that Plato's purpose for the use of myth was didactic. He considered that only a minority was capable of, or interested in, following philosophical reasoning, while the majority is interested in stories and narratives. Thus, he used myths to convey the conclusions of philosophical reasoning. Some of the myths used by Plato were traditional, others were based on modified traditional myths. He eventually he also created new myths of his invention .

On the other hand, the story of the lost city and island of Atlantis came to us as a "true story" through his works Timaeus and Critias , where the character of Critias uses the Greek expression "alēthinós logos", that in those times was used to name a "story that was true", and as such is translated in all the Latin versions of said dialogues, that is, veram historiam , as opposed to myth (from the Greek μῦθος, mythos , 'tale ) or fabled tale. However, the figure of Socrates shows a skepticism towards the story. Later Platonic thinkers will take the story as a metaphorical interpretation .

Topics

The theory of ideas

Unlike Socrates, Plato wrote extensively about his philosophical views, leaving behind a considerable number of manuscripts. His best-known theory is that of Ideas or Forms. It maintains that all the entities of the sensible world are imperfect and deficient, and participate in other entities, perfect and autonomous (Ideas) of a much higher ontological nature and of which they are a pale copy, which are not perceptible through the senses. Each Idea is unique and immutable, while the things of the sensible world are multiple and changing. The opposition between reality and knowledge is described by Plato in the famous myth of the cave, in the Republic. For Plato, the only way to access intelligible reality was through reason and understanding; the role of the senses is relegated and is considered misleading .

Knowledge and opinion

Another theme that Plato dealt with extensively was the dichotomy between knowledge and opinion, which anticipated the more modern debates between empiricism and rationalism, and which was later dealt with by postmodernists and their opponents in arguing about the distinction between objective and subjective . It is important to highlight that the dichotomy between an intelligible world and another sensible world is rather a pedagogical resource that is often used to illustrate the ontological difference between intelligible and sensible entities.

Ideal government

Concepts of forms of government can be seen in Plato's writings, including aristocracy as the ideal; as well as timocracy, oligarchy, democracy and tyranny. A central theme of his work is the conflict between nature and the beliefs of the time concerning the role of heredity and the environment in the development of personality and the intelligence of man long before the debate on the nature and nurture of Man began in the time of John Locke .

Women rights

Greek philosophy conceptualizes man as a (male) citizen of the polis. While Aristotle denies the existence of the highest human qualities to slaves and women, Plato in Book V of the Republic admits women in the class of guardians and at the end of Book VII acknowledges the possibility of female ruling philosophers, however, this admission of women in male activities would only be dictated —according to analysts of his work— by a utilitarian criterion, since the objective is to eliminate the private.Plato's attitude towards women was ambivalent. In some of his writings he advocated fairer treatment for women. On the other hand, he attributed the inferior status of women as a degeneration of men .

Philosophy

Theology

Platonic thought may have had a wide range of theological or religious elements. These elements could be the basis of their ontological, epistemological, political and epistemological approaches. Even in the dialogue Timaeus Plato presents a cosmogonic and religious theory.

This religion was surely adopted from Socrates and must be related to the trial (because in the explanatory statement to the punishment are corrupting youth and asebeia (ἀσέβεια, asébeia ): bringing new gods and denying existing ones) . It probably contained monotheistic (present in the ultimate "Truth" or ultimate "Good" found in his ontological and political theories) and Orphic (due to the reincarnation of the soul) elements. In the dialogues of his youth, Socrates appears defending certain religious beliefs such as that the gods are completely good and that no one really knows what happens after death .

Plato's theological theories were possibly esoteric (secret). Even in Letter VII Plato states: "There is not and never will be a work of mine dealing with these subjects [...] Any serious person would be very careful not to entrust serious matters in writing, exposing them to the malevolence of the people" (341c) . These comments by Plato suggest that what he left in writing is not, for him, "serious" enough. According to Aristotle's confessions in On the Good , the staligite did not have access to these doctrines, unlike Epeusippus and Xenocrates –which would give an idea of why Aristotle did not adopt the Academy–.

In the Republic , Plato condemned atheism (understood as an atomism). He argued that the universe did not arise from the random combination of corporeal elements without any intelligence behind them. He used a kind of cosmological argument in favor of a source of movement that moves by itself, which is the spirit or the soul, the source of cosmic movement. God is for Plato the absolute being, supreme good, creator of all things. things .The world has had a beginning. Indeed, the world is visible, tangible, corporeal; everything that has these qualities is sensible: and everything that is sensible and is subject to opinion accompanied by sensation, we already know, is born and engendered. Furthermore, we say that everything that is born necessarily comes from a cause. What is in this case the author and the father of this universe? It is difficult to find it; and, when he has been found, it is impossible to make him known to the multitude.Secondly, it is necessary to examine according to what model the architect of the universe has built it [...] If the world is beautiful and if its author is excellent, it is clear that he had his eyes fixed on the eternal model [...] ] The universe engendered in this way has been formed according to the model of reason, wisdom and immutable essence, from which it follows, as a necessary consequence, that the universe is a copy.Plato. Timaeus

In the Myth of Er, Plato expresses his vision of the underworld with the existence of rewards and punishments; the involvement of the gods with human choices and the transmigration of souls, which choose their next life:Ephemeral souls, behold, a new career begins for you, expires in a mortal condition. It will not be Fate who chooses you, but you will choose your destiny. Let the one who luckily comes out the first, choose the first his kind of life, to which he will be inexorably united. [...] The responsibility belongs to the one he chooses; there is no fault in Divinity.Plato.

Republic X, 15, 617d-618a.

Ontology and Metaphysics

Various metaphysical topics and concepts are discussed in Plato's dialogues such as being, existence, nature, soul, and body. In his theory of forms, Plato said that reality can only be understood by the rational understanding of forms or abstract universal ideas. Each idea is unique and immutable; on the contrary, material things are multiple and changeable, being only "shadows" of those ideal forms. In Books VI and VII of the Republic, Plato uses various metaphors to explain his metaphysical and epistemological ideas: the metaphors of the sun, the well-known "allegory of the cave" and, the most explicit, that of the divided line. Taken together, these metaphors convey complex and difficult theories; this, for example, is the Idea of the Good, which it has as the principle of all being and all knowing. The Idea of Good does this in the similar way that the sun emanates light and allows the vision of things and their generation in the perceptual world (see the allegory of the sun).

Platonic dualism

Platonism has been interpreted as a form of metaphysical dualism, sometimes referred to as exaggerated or platonic realism. According to this, Plato's metaphysics divides the world into two different aspects:

- The intelligible world , which resides the authentic being, immutable, of abstract forms or objects;

- The sensible world , which we see around us in a perceptive, changing and imperfect copy of intelligible forms or Ideas.

Plato thus established the fundamental dualism of philosophy, the distinction between idealism and materialism, between abstract eternal essences and concrete ephemeral existences, between Parmenidean being and Heraclitus change. This ontological division also leads Plato to a duality in his anthropological and epistemological .

Despite many criticisms of his dualism, Plato refers in the Timaeus to a single universe where both sensible matter and immaterial forms are found (see Cosmology). In a pedagogical way, he unfolds the universe in two and, like someone taking a picture of a landscape, he describes a complex reality in two dimensions. Thus, whoever looks at the landscape will realize that it is impossible for the landscape to 'be' merely what the photograph shows. However, a natural object is not properly a "photographic" copy of the Ideas (since these belong to a different order from that of physical things) but rather an imaginative and symbolic transmission of these .

The forms

The "Forms" or "Ideas" (Greek: morphé and eîdos ) are transcendent, unitary and immutable essences or entities that structure the plurality of things. The Forms are outside of time, like the noumenal world of Immanuel Kant. They are only understandable through the intellect or understanding, that is, the ability to think about things by abstracting them from how they are given to the senses. The ideas are the being of the thing and are subsistent, they exist by themselves, not only in the human mind. For example, in mathematics, the ideal circle consists of an infinite number of infinitesimal points. Such infinity is never realized in the material world, so an ideal circle could be said to have an immutable and eternal nature. (See:

Therefore, Plato's Forms are universal and represent the true reality of things themselves, as well as properties, patterns, and relationships, which we refer to as objects. For example, fair and beautiful things lead us to the Idea of justice and beauty, which if they did not exist, such things would not exist. As they do not manifest themselves in this world and are only perceived through direct intuition by reason, they must exist in another, separate from ours. According to Plato, the "Idea of Good" is the supreme Form, "cause of science and truth", which "provides the truth to the objects of knowledge and the faculty of knowing the one who knows" .

However, Plato collects a series of aporias of his theory in the Parmenides , for example: how many particulars can "participate" in a single Form; how forms interact in the material world by being separated from it; or why one Form does not participate in another (third man argument) .

Cave allegory

In book VII of “ The Republic ” (514a-516d), Plato presents the myth of the cave, a metaphor for our education and its absence. It serves to illustrate his epistemological theory, but also has implications as in ontology, anthropology, and even politics and ethics .

In the allegory, Plato compares the unformed people in the Theory of Forms to prisoners chained in a cave. Having no knowledge of the real world, the shadows cast on the wall by a fire are the ultimate truth to them, but when one is freed and sees the objects and the fire, then they realize their mistake. Once man has assumed this new situation, he appreciates the new exterior material reality of the cave (trees, lakes, stars, etc.), the foundation of the previous realities and finally he appreciates the Sun, the metaphor of the idea of good .

In the perceptual world, the things we see around us are but a slight resemblance to the more real and fundamental forms represented by Plato's intelligible world. It is as if we saw a shadow of things, without seeing the things themselves; these shadows are a representation of reality, but not reality itself.

Epistemology and epistemology

Plato's views also had much influence on the nature of knowledge and teaching which he proposed in the Meno , which begins with the question of whether virtue can be taught and proceeds to expound the concepts of memory and learning as a discovery of prior knowledge and opinions that are correct but not clearly justified.

Socrates stated that "Man is capable of knowing the truth, of overcoming opinion, rising to the knowledge of concepts, of the universal." And his pedagogical practice and his "maieutics" led him to deduce the universal concepts that are present, even in the soul of the most ignorant man, who, if correctly guided, discovers them.THEET. - What do you call thinking?SOCRATES. - To the discourse that the soul has with itself about the things that it submits for consideration.Plato.

Theaetetus 189e.

For Plato, knowledge aims to find an unequivocal definition to know all things. The highest knowledge will then be the knowledge of the universal and the lowest will be the knowledge of the particular. This doctrine supposes an irreconcilable separation between Universal knowledge and the real world, but for Plato this concept of the Universal does not imply an abstract form, but rather that each of these universal knowledge corresponds to a concrete reality .

For Plato it is the ideas that can be known in an accessible way, but he does not deny reality to the world of things. However, Plato could not determine what is the relationship between the particular and the universal.

Plato explains this problem more clearly when he refers to art, he tells us that the artist represents a third version of man. According to Plato, the ideal man is the goal that all humans try to achieve, then there are particular men who are copies of the ideal and finally there is the artist who imitates a copy. For example, in Geometry, one starts from a hypothesis and continues to advance through a visible diagram to reach a conclusion. The geometer supposes a geometric figure from graphs and figures, trying to distinguish objects that can only be seen with intelligence.

Through abstract reasoning and having understood the principles, the mind can draw conclusions without counting on the visible images.

Plato assumes that the knowledge of the real can be achieved in an absolute way, but the same does not happen with the things of the sensible world, which for him is illusory and subject to change. Reason why they cannot be the object of scientific knowledge.

Reminiscence

The doctrine of reminiscence knowledge is based on the Pythagorean doctrine of recollection and appears in the dialogues Meno , Phaedo and Phaedrus . The theory arises as a response to the paradox raised by Meno:And what means will you adopt, Socrates, to investigate what you do not know at all? What principle will guide you in the investigation of things, which you are absolutely ignorant of? And even if you did find virtue, how would you recognize it, having never known it?Plato. Meno

To answer this question, Socrates uses the concept of "reminiscence" or "anamnesis" is a fundamental notion in Plato, which is that knowledge is innate in the human soul and knows the forms of the world of ideas before incarnating in the body. Therefore, "know" is "remember". This theory is a complement to the Socratic method theory since it encourages the student to discover a truth within himself through questions. This theory is a complement to the Socratic method theory, since it encourages the student to discover a truth within himself through questions .This section is an excerpt from Substantial Form § Platonic Forms.

Plato maintains in the Phaedo regarding our knowledge of equals :Did we experience something similar with respect to the logs and the same things that we were talking about now? Is it that they do not seem to be the same as what is equal in itself, or do they lack something to be of the same kind as the equal in itself, or nothing? [...]

Therefore, do we recognize that, when one sees something and thinks: what I now see pretends to be like some other real object, but lacks something and does not manage to be like it, but is inferior, necessarily the one who thinks this must have been able to see before what it says that this resembles, and that it is inferior to it? [...]So it is necessary that we have previously seen the same thing before that moment in which, when seeing the same things for the first time, we think that they all tend to be like the same but that they are insufficiently so.Plato.

Phaedo 74d-75a.

Ways of knowing

Plato distinguishes various degrees of knowledge based on Parmenides. He differentiated between: doxa and episteme:

- Knowledge of sensible things ( Doxa ): It is called by Plato doxa (opinion or appearance) the perception of the sensible world, the path between truth and ignorance. Since it does not have a true entity, there can be no authentic knowledge either, but merely opinion. In turn, opinion has two modes: divided into beliefs (pistis) and knowledge of appearance or imagination (eikasía) .

- Imagination ( Eikasía ): Through eikasía or imagination, the images of things, their shadows and reflections are learned, being the lowest degree of the scale of knowledge. We cannot imagine an object endowed with less consistency than the extreme transience of a shadow. Possibly Plato is thinking of activities such as poetry, painting or rhetoric. Indeed, both the speaker and the poet or the painter are only interested in a mere plausible imitation of reality and for this the production of images is enough for them.

- The belief ( Pistis ): In the pistis there is a degree of knowledge superior to the previous one since it is already about an object itself and not about an image of it. The various productive arts, such as carpentry, would fit in here perfectly: the carpenter knows more about the table than the painter who represents it on canvas because a mere credible appearance of the table is enough for the latter, while the carpenter he has to make a "real" table .

- Intelligible knowledge ( Episteme ): Episteme (science) is true knowledge, which comes from the true immutable reality of Ideas.Itsobject is intelligible reality, the perfect and immutable being: ideas. There are also two degrees here, discursive knowledge (dianoia) and pure intelligence (nous):

- Discursive knowledge ( Dianoia ): As an example of diánoia, Plato thinks of arithmetic or geometry. In both, one always starts from hypotheses or presuppositions and needs (Plato thinks) sensible symbols. Mathematics proceeds according to a type of reasoning that we could call "hypothetical-deductive", that is, it goes from the hypothesis to the conclusion by deduction.

- Knowledge or pure intelligence ( Nous ): The nous is the overcoming of the diánoia through dialectics, considered as the "culmination of all sciences". This is about assuming what we want and discussing that thesis through an introspective dialogue or with another person.Only she is capable of canceling the merely hypothetical character of the principles used in the remaining disciplines, by giving reason for them and justifying them rationally. To achieve this, the dialectic has to go back to a non-hypothetical principle from which it can deduce everything else as consequences. It is clear that this non-hypothetical principle, object of the dialectic, is none other than the idea of the Good. Through it, knowledge of the relational structure of ideas is achieved, and ultimately, knowledge of the supreme truth, condition (foundation) of the ideas themselves and, therefore, also of the sensible world: The idea of the Good .

His vision of these changed during his life. In the first dialogues he understood the doxa as a subjective judgment and the episteme as a skill. While in the Symposium he praised doxa as an essential means to attain virtue in the episteme , in The Republic he regards all doxa as dangerous and opposed to the episteme .

Simile of the line

In book VI of his work The Republic, Plato uses the analogy of the line to express the two regions of reality, their divisions and the types of knowledge that correspond to them .

| D | C | B. | TO | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| sentient world | intelligible world | ||||

| Shadows / images | physical objects | mathematical objects | Ideas or Forms | ||

| Dialectics |  Reminiscence Reminiscence | idea of good | |||

| Imagination | Belief | discursive reason | intuitive reason | ||

| Opinion (doxa) | Science (episteme) |

- In the first segment of this line he places the objects that are perceptible by the senses and at the same time divides them into two classes and refers for each type of object a way (or operation) in which the soul knows these objects. The first are the images or shadows that emerge from physical objects, images from which almost zero knowledge can be obtained, therefore, the human being imagines what these shadows can be. In the second division of this first segment, he places the physical objects that fulfill a double role, they are generated by what he will call inferior and superior intelligible beings while with other elements (ie light) they generate shadows. To these corresponds the operation of belief .because being in constant change due to being subject to time and space they never 'are'.

- In the second segment of the line, Plato establishes the objects that, without being able to be perceived by the senses, are perceived by the soul and are the generators of those that were in the first segment of the line, and he also divides it into two. In the first part of this second segment he settles the lower intelligible beings, the mathematical and geometrical principles. These entities still have some kind of relationship with the sensible part of the universe because they can be represented (for example, a square, the number 4, the odd with respect to the even, etc.); the operation carried out by the soul to apprehend these concepts is the understanding. In the last part, he settles the superior intelligible beings, those ideas that can only be defined by others and that in no way can be represented for sensory perception (ie justice, virtue, value, etc.); to understand them the soul disposes itself towards them using intelligence .

Thus for the first section Plato understood that imagination and belief, that is, the mere description of what is perceived, can result in an opinion. However, understanding and intelligence are for Plato those operations from which knowledge is obtained.

While interpretations of Plato's writings (particularly The Republic) have had immense popularity in the long history of Western philosophy, it is also possible to interpret their ideas in a more conservative way that favors reading from an epistemological point of view rather than a metaphysical one, as would be the case of the metaphor of the Cave and the Divided Line (however, there are also important authors who speak of the need to make a phenomenological interpretation of Plato in order to see the author beyond the historical layers that cover him due to his other less fortunate interpretations). There are obvious parallels between the allegory of the Cave and the life of Plato's teacher, Socrates, who was executed in his attempt to open the eyes of the Athenians.The Republic , who narrates the story is Socrates)

Justified true belief

Many have interpreted Plato as stating that knowledge was essentially based on justified true beliefs; an influential belief that led to the further development of epistemology. In the Theaetetus , Plato distinguishes between belief and knowledge by means of justification. Justification is a rational explanation of belief. True opinion accompanied by reason is knowledge .

Although "justified true belief" is the traditional philosophical definition of knowledge, the ancients were already skeptical of this Platonic idea. Socratic dialogues usually did not reach any positive conclusion; they were "negative dialectics". Years later, Edmund Gettier would demonstrate the problems of justified true beliefs in the context of knowledge. Plato himself also identified problems with the definition of justified true belief in Theaetetus , concluding the definition of knowledge is circular .So, Theaetetus, epistēmē would be neither sensation nor true belief nor logos supervening true belief.Plato.

Theaetetus 210a9-b.

Because the object of knowledge must be unmodifiable, stable and permanent to achieve its definition clearly. Knowledge is achieved through judgments about universal concepts and not about particulars, and only judgments about what is permanent and stable can be true. Neither sensible perception nor true belief can be the object of knowledge. An infinite regress arises when we ask what are the justifications for the reasons themselves .

Anthropology and psychology

Platonic anthropology divides the human being into an entity composed of two antagonistic elements, body (material) and soul (immaterial), with the soul having priority and prevalence over the body. Plato elaborated a tripartite theory of the soul in his dialogue On him The Republic , and also with the allegory of the winged chariot in the Phaedrus . In the Republic and in the Timaeus , Plato stated that the soul ( psyche ) is made up of three parts :

- Rational soul , (λογιστικόν); immortal, intelligent, divine and located in the brain; her virtue is prudence and wisdom.

- Wrathful Soul , (θυμοειδές); source of noble passions (courage, courage, strength), is located in the chest and dies with the body. Her virtue is strength.

- Concupiscible soul, (ἐπιθυμητικόν); source of ignoble passions (appetites, bodily desires), is located in the womb and is mortal. His virtue is temperance.

The rational soul is a substance that moves by itself. For Plato, the body is the prison of the soul, and it aspires to return to the world of Ideas. For this, there must be a harmony of souls. The references to the immortality of the soul, as well as the first attempts to deal with the demonstration of it, are found in the transitional dialogues; although it will be in the dialogues of maturity that the tests are developed, the belief in immortality being ratified in the Timaeus . Plato conceives immortality only of the rational soul. He argued in the Phaedo for the immortality of the soul on the basis of its simplicity. In the Meno , he defends the thesis that the soul lives without the body in the world of Ideas ( anamnesis). Aristotle pointed out that Plato's theory of the soul coincides with that of Empedocles, where the soul is composed of the four elements. Plato found in him his theory of vision. similar is known by similar, both postulate that the fire within us, similar to the external fire, flows in a subtle and continuous way through the eye thus allowing vision. Plato provided his version of metabolism: food nourishes all parts of the body, thus blood is formed in the womb, seat of the appetitive soul, by the action of fire and from there it is distributed throughout the body. The lungs revive the air, to keep the internal fire. The body's organs take substances from the blood to repair themselves.

Plato's politics and ethics are based on his anthropology, and this on his epistemology and ontology.

Politics

Plato's philosophical ideas had many social implications, particularly regarding the ideal state or government. There are discrepancies between his initial ideas and those he expounded later. Some of his most famous doctrines are set forth in the Republic . However, with modern philological studies it has been implied that his late dialogues ( Politics and Laws ) present a strong criticism of his previous considerations, this criticism will arise as a result of Plato's enormous disappointment with his ideas and the depression shown in Letter VII.

Justice

The government must be based on the consent and harmony of the true knowledge of what is good for the citizenry. For Plato, the most important thing in the city and in man would be Justice. Therefore, his State will be based on an ethical need for justice. Justice will be achieved from the harmony between social classes and, for individuals, in the parts of the soul of each one.

Plato said that societies should have a tripartite class structure which responded to a structure according to the appetite, spirit and reason of the soul of each individual:

- Artisans or farmers – The workers corresponded to the “appetite” part of the soul.

- Warriors or guardians – The adventurous, strong, brave warriors who formed the “spirit” of the soul.

- Rulers or philosophers – Those who were intelligent, rational, fit to make decisions for the community. These formed the "reason" of the soul.

To preserve social harmony, Plato considers a noble lie that the rulers will use to convince the people. In the myth of metals, differences in human nature are justified due to different proportions of three metals in the soul ( gold, silver and mixture of iron and bronze) placed by the gods .

| craftsmen | guardians | rulers | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Soul of the: | concupiscible soul | irascible soul | rational soul |

| Virtue of the: | Temperance | Strength | Prudence |

| Own metal of: | iron and bronze | Silver | Gold |

Philosopher king

According to this model, the principles of Athenian democracy, as it existed at that time, were rejected in this idea and very few were able to govern. This contempt for democracy could be due to its rejection of the trial of Socrates. Instead of rhetoric and persuasion, Plato says that reason and wisdom (episteme) should rule. This does not equate to tyranny, despotism or oligarchy. As Plato said:Until the philosophers rule as kings or, those who are now called kings and the rulers or leaders, can properly philosophize, that is, until the political and the philosophical power agree, while the different natures seek only one of these powers exclusively, the cities will not have peace, nor will the human race in general.Plato.

Republic V, 473d.

Plato describes these "philosopher kings" as those who "love to see the truth wherever it is with the means available" and supports his idea with the analogy of a captain and his ship or a doctor and his medicine. Navigating and healing are not practices that everyone is naturally qualified to do, regardless of wealth, beauty, or even gender:Therefore, dear friend, there is no occupation in the city regiment that is proper to women as such women or to men as such men, but the natural gifts are scattered indistinctly in one and the other beings, so that the women have access by nature to all tasks and men also to all; only that the woman is in everything weaker than the man.Plato.

Republic V, 455d.

However, Plato's attitude towards women was ambivalent. While in his Republic he abolished their property status and puts them on the same level with men for both the guardian and ruling classes, on the other hand he admitted as the Aristotelian view of women that they are a degeneration of human nature. perfect. It says in the Timaeus :All the cowardly men who led an unjust life, according to the probable discourse, changed into women in the second incarnation.Plato,

Timaeus 90e.

Much of The Republic is dedicated to indicating the educational process necessary to produce these "philosopher kings", in fact the ideal Platonic State will be largely an entity dedicated to education. All citizens would go through a long system of education with the aim of creating citizens committed to the common good and determining their social role. To prevent rulers from abusing their power, they were required to lead austere lives without owning money or property, or having a family life .

In the work Politician , Plato is the one to explain that political power needs a specialized type of knowledge or gnosis to govern correctly and justly, in addition to representing the best interests of its citizens. This dialogue is directed against those who rule in Greece at that time: those who give the appearance of possessing such knowledge, but in reality are only sophists. There he presents The Myth of the Divine Shepherds .

Ideal state

The foundation of the ideal State in the Idea of Good. It should be mentioned, however, that the idea of the city described in The Republic is qualified by Plato as an ideal city, which is examined to determine how injustice and justice develop in a city. According to Plato, the "true" and "healthy" city is the one described in Book II of The Republic , which contains workers, but does not have philosopher-kings, poets or warriors.

In any case, for Plato the ideal State (Monarchy) will become a sad but necessary corruption. Thus Plato establishes the categories of the different states in an order from best to worst :

- Monarchy or aristocracy, which would be the most perfect form.

- Timocracy or military regime.

- Oligarchy, where a minority rules.

- Democracy, government of the people, imperfect for Plato.

- Tyranny, the most perverse of regimes.

The aristocracy or monarchy corresponds to the ideal state with its tripartite class division (Philosophers-Guardians-Workers). In the best State , all things must be established according to the proverb: everything is common among friends . of theater and the public word.

Plato proposed a communist constitution that abolishes families and limits private property to a part of the city, unlike modern communism, and the monarchy, but in turn he ended up defending the laws as a system of government —more like submission to the circumstances than by true preference. Likewise, he is perhaps the first to defend equality between the sexes, unlike his disciple Aristotle. The State also establishes the eugenic guidelines that should regulate the marital and reproductive life of the city. The rulers would reproduce with pairs approved by the State to produce the best offspring .

In Laws , Plato renounces his earlier radicalisms (government by philosophers, abandonment of private property and families) as practical impossibility. The perfect State must be seen as a paradigm of a constitution to follow. Here the rulers without those who more rigorously obey the divine law in whose hands is the objective to which everything must be looked at .

Ethics

Various dialogues discuss ethics, including virtue and vice, pleasure and pain, crime, punishment, and justice. In the Republic , Plato sees "The Good" as the highest Form, somehow existing even "beyond being", attainable by a few through true episteme . In the Gorgias Plato argues against identifying the good with pleasure and against the morality of the "Superman" proposed by Callicles .

In the Philebus it is stated that the good life can do without neither pleasure nor intelligence and that the proportion with which these components are mixed comes from intelligence, not from pleasure. Plato distinguishes three pleasures: those that fill and replace a pain; those that do not fill a lack and the pleasures; of the philosopher do not fill a painful lack and are genuine pleasures. Against the hedonistic assumption, the pleasures of the philosopher are more substantial than the pleasures of the flesh. However, pleasure is a misleading guide to happiness .

Socrates proposed a moral intellectualism that affirmed that nobody did it wrong on purpose, and knowing what the good results are to do what is good; that knowledge is virtue. In the Protagoras dialogue it is argued that virtue is innate and cannot be learned. For Socrates, all ethics must begin with self-knowledge. Socrates already conceives of virtue as the correct behavior for that purpose or activity for which something is done, that is, the behavior appropriate to nature. Similarly, Plato builds his ethics on the pillars of his conception of happiness and virtue .Isn't it the same with runners who run well at the start and poorly at the end? [...] even if they cover up during their youth, they are caught at the end of their career, they make a laugh out of it and, when they grow old, they are ruthlessly harassed by outsiders and fellow citizens, they are flogged and in the end they suffer.Plato.

Republic X, 613b-e.

Plato had intended to lay ethics on solid foundations, moving away from the confused relativism of the sophists and turning it into an exact science, the science of good. Plato's ethics aims to study how the human being can approach the world of ideas and, ultimately, the contemplation of the idea of Good. Thus, ethics is reduced to the theory of forms. The supreme good of man can be said to be the authentic development of his personality as a rational and moral being, the right cultivation of his soul, the general and harmonious well-being of his life .

Plato's ethics is a eudaemonistic ethics, that is, an ethics that establishes that the end that all human beings wish to achieve in life is happiness, both individually and collectively. Happiness is the Therefore, happiness and virtue are closely linked. The platonic cardinal virtues already exposed in his politics are justice, prudence, fortitude and temperance .

Plato presents under the figure of Socrates the famous dilemma of Euthyphro in the dialogue of the same name, in which he criticizes divine law as the basis of morality (theory of divine mandate). For Plato, evil is necessary, fatal, and inevitable in the world because of matter, independent of God. In the Republic , Plato used the myth of the Ring of Gyges to consider whether a person would be righteous if he did not have to fear for the ethical consequences. In Laws , good is not considered as knowledge, but as a rational harmony of the elements that make up man. Plato no longer considers the emotions as a threat to the virtues. The ethical problem is no longer one of finding out what the Good is, but of how to make men live a good life.

Esthetic

Beauty and love

Beauty for Plato is a kind of universal form, so perfect beauty exists only in the eternal form of beauty. Plato argued for a timeless idea of beauty independent of and superior to that of the imperfect world of the senses. In his dialogue Hippias Major , his teacher, Socrates tries to establish a definition of beauty. There are beautiful vessels, women and men, but only physically. Beauty as such is wisdom. Socrates concludes this dialogue with the proverb: " What is beautiful is difficult " .

Beauty in Plato also covers the moral and cognitive fields. In the Symposium, for Plato beauty and good were synonymous terms. In this same dialogue, under the figure of the philosopher Diotima, he expresses the concept of platonic love with a ladder that reaches up to divine knowledge. Two types of love were differentiated: the physical (to the body) and the spiritual (to the soul, the latter brings us closer to divine knowledge). Also in that dialogue, Diotima presents the "ladder of love", through which the lover can ascend to the form of Beauty, being erotic love as degraded forms. For Plato, love is a "volitional" element and that he conceives as an impulse towards beauty, wisdom and good. In the Symposium, Aristophanes presents the myth of the Androgyne, according to which there was a being who brought together in his body two sexes (of the same or opposite). These beings tried to invade Mount Olympus, where the gods live, and Zeus, realizing it, threw a lightning bolt at them that divided them into male and female. Since then, it is said that the man and the woman go through life looking for their other half (see Half orange). However, Plato declares in the Phaedrus that love is revealed as "divine madness" and beauty is different from wisdom because it can be manifested through the senses. In such a dialogue, he considered that the contemplation of imperfect beauties awakens in us the memory of the very essence of beauty .

Art and poetry

Various dialogues address questions about art, including rhetoric and rhapsody. Socrates says in the Ion that poetry is inspired by the Muses and is not rational, rejecting all technique. He speaks approvingly of this and other forms of divine madness (drunkenness, eroticism, and dreams) in the Phaedrus , and however, in the Republic he condemned art along with literature and rhetoric as "a vile thing", expelling the poets from their ideal city. He wants to ban poetry. On the other hand, in law, Plato gives two functions to art: that youth have fair feelings and on the other hand be a source of rest for maturity. Here the art is subordinated to the good. In that dialogue, Plato spoke about the laws on music with moral criteria. He had a low esteem for common men, as they lack criteria regarding music and theater, preferring the vulgar .I agree with the common people that it is necessary to judge music by pleasure, but, by the way, not by anyone's, but I dare to say, the most beautiful Muse is the one that delights the elderly and sufficiently educated , and, especially, the one that provides pleasure to the only one who is distinguished by his excellence and his education.Plato.

Laws 659a.

For Plato, the origin of art must be placed in the natural expressive instinct. The nature of art for Plato is not the invention, but the mimesis, the "material copy", of the idea of beauty. But "the race of poets is not capable of knowing what is good and what is not" and "the creator of ghosts, the imitator, understands nothing of being, but appearance". As every copy is always imperfect, the artist acts as a sophist, a liar who lives by appearance and is carried away by passion. On the other hand, Socrates gives no indication in the Ion of the disapproval of Homer that he expressed in the Republic and suggests that the Iliadit functioned in the ancient Greek world as divinely inspired literature that can provide moral guidance, if only it can be properly interpreted.

Cosmology

It is presented mainly in the Timaeus , although there are cosmological elements in other texts (for example, in the Phaedo and, more particularly, in the Laws ). The introduction to the Timaeus suggests that the presentation does not guarantee accuracy, which shows Plato's recognition of the weakness of knowledge oriented to the sensible world and attainable through our sensations. In the Timaeus , Plato is concerned with the structure of the visible heaven as a model for the human soul, and also with the material conditions of human physiology .

According to the traditional interpretation of the metaphysics of the Timaeus , matter exists eternally and independently. The proper character of matter for is indeterminacy (apeiron). Plato calls Jôra a chaotic empty space that will serve as a place where matter is installed. However, Plato goes so far as to give the Jôra in the Timaeus certain material properties, referring to it as a kind of "formless clay" or "mother". from which the establishment of the material order proceeds. Plato uses the figure of the Demiurge, who plays the role of creator of the sensible world. The Demiurge does not create ex nihilo , but orders matter using ideas as a paradigm of the cosmos .Then, the world is the result of God, Ideas and matter .

Plato described the Earth in the shape of a globe and the spherical universe, being the most perfect figure, created by the Demiurge, being also finite and limited. Aristotle refers to Timaeus in his work On Heaven in which Plato expresses that the Earth rotates around its own axis in the universe. However , in the Phaedo , Plato affirms the immobility of the Earth, and in the Phaedrus , where a profession of Olympian gods is presented, Hestia is said to , the Earth divinity, "remains in the abode" .

The world is surrounded by the fixed stars and constituted by the seven celestial spheres (the Moon, the Sun, Venus, Mercury, Mars, Jupiter and Saturn). At its center resides the universal soul. The stars could be considered as divine and immortal living beings. Plato also associated each of the four classical elements (earth, air, water and fire) with a regular solid (cube, octahedron, icosahedron and tetrahedron).Due to their shape, the so-called platonic solids. There was a justification for these associations: the heat of the fire seems sharp as a piece of tetrahedron; air is an octahedron as it resembles fire; the water to the icosahedron because it escapes from the hand when it is grasped as if it were made of tiny balls; and the earth represents the most stable solid, the hexahedron. The fifth regular solid, the dodecahedron, was supposed to be the element that formed the heavens because it is the solid that most closely resembles the sphere, the most perfect shape. Aristotle named this fifth element the ether.

- The five regular convex polyhedra (platonic solids)

tetrahedron

tetrahedron hexahedron

hexahedron Octahedron

Octahedron Dodecahedron

Dodecahedron icosahedron

icosahedron

Later influence

In philosophy, Plato is a reference for rationalism and idealism. Regarding the historical influence of Plato it is difficult to exaggerate his achievements. Platonic work sows the seeds of philosophy, politics, psychology, ethics, aesthetics or epistemology. In covering this subject we must also consider his student, Aristotle, who postulates the beginnings of logic and modern science.

Cicero's political theory has Plato as a reference. Various Christian and Muslim authors found a great affinity between Plato's thought and the ideas of the new faith, which helped them to articulate them philosophically, as is the case of Saint Augustine, for example. Plato's metaphysics, and particularly the dualism between the intelligible and the perceptual, later inspired Neoplatonic thinkers, such as Plotinus, Porphyry, and Proclus, and other metaphysical realists. Fathers of Christianity, such as Augustine of Hippo, and the so-called Pseudo Dionysius were also greatly influenced by his philosophy. Boethius translated some works of Plato. John Scotus Erigena fused Neoplatonism and the Christianity of Pseudo Dionysius in pantheistic terms .