Pisco from Peru

The Peruvian pisco is a denomination of origin that is reserved for the alcoholic beverage brandy made from grapes that has been produced in Peru since the end of the century XVI. It is the typical distillate of this country, made from the fermented wine of certain varieties of grapes (Vitis vinifera), whose value has passed its borders, as attested by the records of shipments made through the port of Pisco to Europe and other areas of America since the XVII century, such as the United Kingdom, Spain, Portugal, Guatemala, Panama, and the United States, since the mid-XIX century.

It is one of the flagship Peruvian products and is only produced on the coast (up to 2,000 meters above sea level) in the departments of Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna.

About the denomination of origin "pisco", there is a controversy between Chile and Peru.

Background

In the southern Quechua language, spoken in much of Peru at the arrival of the Spanish, the word pisqu (pronounced [pis.qu], also found in chronicles as pisku , phishgo, pichiu) designates small birds. It is part of the name of the toponymy of several regions of the country, both via southern Quechua and through other varieties of Quechua, where it is usually found in the form pishqu and similar.

The Peruvian coast has been characterized by hosting huge populations of birds that feed on the abundant amount of fish, especially in the so-called "Sur Chico". In this range are the valleys corresponding to the Pisco, Ica and Grande rivers.

In the valley of Pisco, a human group inhabited more than two thousand years ago, noted for its ceramics and which, at the time of the Inca Empire, was characterized by its remarkable pottery products, called piskos.

Since that time, one of these pottery products were containers or amphoras, which were used to store all kinds of beverages, including alcoholic beverages. These vessels were called piskos.

In this way, the first grape brandy produced in Peru was stored in piskos and, over time, this alcoholic liquid acquired the name of its container. [citation required]

In addition, the Royal Spanish Academy, in its Dictionary of the Spanish language, recognizes the origin of the term "pisco" from Pisco, a city in the department of Ica in Peru.[citation required]

History

16th and 17th centuries

The first vine plantations in Peru

With the founding of Lima in the year 1535, as the City of Kings, the first stones were laid for the building of churches in Peru and with it the need to supply wine for the celebration of liturgical acts was born. In order to achieve this objective, the first vine plantations began on these lands, in the most fertile areas.

The first vine arrived in Peru at the end of the first half of the XVI century, coming from the Canary Islands. The Marquis Francisco de Caravantes was in charge of importing the first grape shoots received from these islands. One hundred years before (1453), Chuquimanco, cacique of the lands to the south of Lima, contemplated at sunset flocks of little birds that crossed the sea horizon, in search of islands to rest;[citation needed] were thousands of birds that Chuquimanco knew in his language as pishqus.[ citation needed] They inspired their pottery people and gave it their name. This is how Pedro Cieza de León narrated it in 1550 in The General Chronicle of Peru: «pisco is the name of birds».

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the Viceroyalty of Peru became the main wine producer in South America, its epicenter being the Ica Valley, where Jerónimo Luis de Cabrera founded, in 1563, the " Villa de Valverde del Valle de Ica" (current Ica). In 1572, the town of "Santa María Magdalena del Valle de Pisco" was founded. Cuzco, where the first winemaking in South America took place".

The birth of pisco

At first, grape production was used solely for winemaking, but little by little brandy also made its way. According to the Peruvian historian Lorenzo Huertas, the production of grape brandy in Peru began in the mid-XVI; In addition, he adds that the studies of the American Brown Kendall and the German Jakob Schlüpman show that "the expansion of the wine and brandy market occurred in the last third of the 16th century".

In the General Archive of the Indies there is a request made by Jerónimo de Loaysa and others, to "populate in the valley of Pisco under certain conditions", which was approved by the Spanish Crown on February 10, 1575. In the same archive, there is a copy of a royal provision of November 26, 1595, by which Agustín Mesía de Mora was given the title of "notary public, of mines and records and dispatches of ships of the port of Pisco, in Peru".

Peruvian researcher Emilio Romero points out that, in 1580, Sir Francis Drake raided the port of Pisco and demanded a ransom for the prisoners he took; To complete the ransom, the villagers paid him 300 jugs of brandy from the area. Later, in 1586, the sale in Panama of "cooked wine" from Peru was prohibited, ordering "That in the city of Panama [...] no innkeeper [...] can sell or sell in public or secretly any cooked wine [...] Everything that is sold in the taverns and grocery stores of these kingdoms [whether] without a mixture of cooking"; then the export of any kind of wine to Panama would be prohibited, by a provision of December 17 December 1614, which prescribed "That no person [...] can bring wine of any kind from Peru to Panama City".

In 1613, a will was registered in Ica that left documentary evidence of the production of grape brandy in that area. Said will was extended by a resident named Pedro Manuel "el Griego", a native of Corfu Greece dated that year and who is kept in the General Archive of the Nation, in Lima, within the notarial protocols of Ica. In that instrument, said resident states that he possesses "thirty vurney jars full of brandy, plus a barrel full of brandy that had thirty botixuelas of said brandy", plus the technological implements to produce this distilled beverage, "[...] a large copper cauldron for making brandy, with its barrel lid. Two pultayas, one with which the pipe passes and the other healthy one that is smaller than the first one". In any case, it would be possible to conclude the production of brandy some time ago; In this regard, Lorenzo Huertas points out that it must be taken into account "That, although the will was signed in 1613, those instruments of production existed much earlier".

Starting in 1617, the large-scale production of grape brandy sold by the Jesuits in Lima, Arequipa, Cuzco, Ayacucho and Potosí in Upper Peru increased. Lorenzo Huerta indicates that the studies by Brown Kendall and Jakob Schlüpman would show that the expansion of the wine and brandy market "reached unprecedented limits in the 17th century".

The first identification of brandy with the place —“aguardiente de Pisco”— would have been made in 1749 by the peninsular Spaniard Francisco López de Caravantes, when exposing in his “Relation” that it is preserved in handwriting and that it is dated in 1749, that «the valley of Pisco, continues to be the most abundant of excellent wines in all of Peru. From there, one that competes with our Jerez, the so-called “Pisco brandy”, because it is extracted from the small grape, is one of the most exquisite liquors that is drunk in the world ».

In a documentary shown by the History Channel, Peruvian anthropologist Jorge Flores Ochoa explains that this grape brandy began to be made in the town of Pisco and was distributed along the Peruvian coast, even reaching the Chilean coast.

Expansion

The increase in the local production of brandy and wine allowed its export to various parts of the Spanish Empire, which was carried out mainly through the port of Pisco. Trade grew in the mid-17th century century, with shipments bound for various Pacific ports.

Despite the prohibitions that the Crown wanted to impose on the production and trade of wines in Peru, an intense wine-producing activity developed, mainly in the corregimiento of Ica, which generated an important maritime movement on the ocean coast Pacific during this time.

Sample of the former are the provisions of King Felipe III and Felipe IV, issued on May 18, 1615 and June 19, 1626, respectively, and included in Law 18, Title XVIII, Book IV of the Compilation of the Laws of the Indies, by virtue of which the sale of Peruvian wine in Guatemala was prohibited ("That in the Province of Guatemala no trajine, nor hire wine from Peru"). In it, it is pointed out that the city of Santiago de Guatemala represented "that some people bring to the port of Acaxultla in that province many wines from Peru, which because they are strong, new and uncooked, generally cause great damage to the Indians." ", so it would refer to the Peruvian grape brandy, which has a higher alcohol content than wine and requires distillation ("new, strong and uncooked").

Regarding such provisions issued by the Spanish Crown, Lorenzo Huertas indicates that "It is said that the famous Jesuit provincial Diego Torres Bollo managed to get the king to repeal such prohibition." In turn, the historian Jakob Schlüpman, based on in the study of the declarations of the colonial maritime trade of the region, indicates that despite the restrictions on the trade of "wine from Peru", it continued to be carried out in the corregimiento of Ica.

During the government of the Viceroy of Peru Pedro de Toledo y Leiva, I Marquis of Mancera, in 1640, Pisco was founded as a “villa”, under the name of “Villa de San Clemente de Mancera”, although it was always popularly known as "Villa de Pisco". Later, in 1653, the chronicler Bernabé Cobo, in the "Historia del Nuevo Mundo", would describe that "The Indians of the mountains and the coast highly appreciate chicha, but even more the brandy that is distilled in the valley of Pisco, from which it takes its name. They store it in sandstone jars called “botijas”».

Since 1670, the valleys of Ica and Pisco mainly exported grape brandy in “botijas de Pisco” and from the beginning of the XVIII century such export was greater than that of the wine itself. The reason for this conversion was the distillation of the residues and the wines turned into vinegar, which can be seen in a document from the General Archive of the Nation of Peru, where it indicates that "of the 153 jugs of wine standing with shells and waste, 15 peruleras of brandy came out. And of the 137 jugs of wine from the Bentilla de Alarcon hacienda that were culled to recognize that it was turning into vinegar, 19 peruleras of brandy came out [...] For the shipment of 137 jugs of wine, which were brought from said hacienda of the bentilla de las separadas at little size to get spirits for half a real".

In 1684, the main customs office of Pisco was created in order to control the commercial exchange of the area, while the customs offices of Ica, Palpa and Cerro Azul were created in 1692 and 1693.

In Pisco there were five churches, de la Compañía and San Juan de Dios. It was highly populated until 1685, when it was looted by an English pirate, and was also badly mistreated in 1687... the vines abound, despite the sandy and barren terrain, the vines grow in many places with only the interior humidity of the land... supplies Lima with its wines and spirits and takes some to Panama, Guayaquil and various provinces of the mountains.

The 1687 earthquake, and the tsunami that followed, destroyed Pisco, Ica, and several other towns on Peru's central coast, causing the wine industry as a whole to suffer a sharp collapse.

As a consequence of the above, the town of Pisco had to be refounded in 1689, under the name of "Villa de Nuestra Señora de la Concordia de Pisco", in the vicinity of its original location.

18th century

Peruvian historian Alicia Polvarini points out that «the production of the best grape brandy, known as “aguardiente de Pisco” or simply “pisco”, has been preserved since the 17th century, its refined production conquered European palates towards late 18th century and 19th century", based on the shipments of the sea and land customs guides and the highest price at which the jugs from said valley were sold.

Based on the aforementioned study, the Argentine researcher Pablo Lacoste indicates that the first references to the use of the name "Pisco" to name the Peruvian brandy are found in customs guides, in which it is indicated since 1764, in chronological order, “so many peruleras of brandy from the Pisco region”, “so many peruleras of brandy from Pisco”, to later eliminate the word “aguardiente” and going on to write down directly "tantas peruleras de Pisco", which constitutes a sample of the origin of the use of the denomination "Pisco" for the brandy of Peru based on the geographical location.

Pablo Lacoste points out that, although at the beginning of the XVIII century the area's production consisted mainly of wine, With a lower proportion of brandy, the trend was reversing and by 1767 the production of brandy, which came largely from the Pisco region, represented 90 percent of the total wine production.

Lorenzo Huerta adds that, in the studies by Brown Kendall and Jakob Schlüpman, he realizes that the production of wine and spirits in Peru began to decline gradually in the XVIII.

On the other hand, according to Jakob Schlüpman, it was not until the middle of the XVIII century that it began to receive, from Valparaíso, wines produced in Concepción and at the end of the XIX century brandy from the same port.

19th century

The Englishman Hugh Salvin recounted in 1824 that "The city of Pisco, almost a mile from the beach [...] This district is known for the manufacture of a strong liquor that bears the name of the city [...]". Meanwhile, the Englishman Charles Milner Ricketts indicated in 1826 that "[To] protect the landowners of Pisco in the distillation of their brandy [...] Pisco brandy is preferred [...] also consider the products that Peru exports to Chile and Guayaquil [...] Pisco brandy [...] constitute the items supplied by Peru" For his part, the German Johann Takob Von Tschudi, in "Testimony of Peru", explains in 1838, that "Most of it is distilled brandy, which, as will be understood, is exquisite. All of Peru and a large part of Chile stock up on this drink from the Ica Valley. Common brandy is called Pisco brandy because it is shipped in this port [...]"

The American writer Thomas W. Knox, in the book "Underground" written in 1872, it says that pisco "is perfectly colorless, very fragrant, extremely seductive, terribly strong... but very delicate, with a marked aroma of fruit. It comes in clay jugs, which are wide at the top, and narrow to the top, holding about five gallons..., the first glass satisfied me (and I realized) that San Francisco was, and is, a beautiful city to visit".

The writer Herbert Asbury, in the work entitled "The Barbary Coast", an account of the cosmopolitan life of the city of San Francisco (United States) between the years 1878-1880, narrates that "of the countless saloons (bars) that made San Francisco so famous, the most famous was the Bank Exchange. The Bank Exchange was especially known for its pisco punch. During the 1870s it was certainly the most popular cocktail in San Francisco, despite costing about twenty-five cents a glass, a high price in those days, and was without question the crème de la crème of drinks.. The secret of its preparation was a pisco brandi distilled from the grape known as Italia or Rosa del Perú, and it took its name from the Peruvian port from which it was exported. And the pisco brandi, without any other ingredient that would turn it into a punch, was a drink that well deserved to write home and tell about".

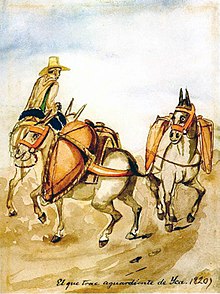

In 1884, Juan de Arona included the term pisco in his «Diccionario de Peruanismos», indicating that this term was the "generic name of the grape brandy that is made on farms near Pisco and that is exported through this port" also noting that "pisco brandy is one of the richest on earth". The author also points out that the terms "pisco" or "pisquito" designated the terracotta jug in which the drink was packaged (see Pancho Fierro's watercolors on the right side).

Rudyard Kipling describes the Peruvian pisco in his book "From Sea to Sea", published in 1899, where he points out that the " pisco brandy botton punch [...] the most noble and beautiful product of our age [...] I have a theory that it is composed of little cherubs' wings, the glory of a tropical sunrise, red clouds of sunsets and fragments of ancient epics written by great deceased masters".

In the middle of the XIX century in Peru, around 150,000 hectares of vines were planted for the production of pisco.

Anecdote related to the pisco trade

The traffic of merchant ships between Peru and the United States of America has always been fluid since the independence of Peru; Many of the Peruvian ships made the maritime route between the ports of Pisco and Callao and the US port of San Francisco, carrying pisco from Peru, among other products, since the 1830s. In the 1840s The gold rush broke out in western California, attracting all sorts of adventurers, the unemployed, the underemployed, and even the crews of the ships that did commercial traffic with the United States from all parts of the world, including the From Peru.

In 1848, in the port of San Francisco there were several Peruvian merchant ships without crew, who had abandoned their ships attracted by the gold rush; The Government of Peru decided then to send a ship from the national navy to the Californian port to safeguard Peruvian naval interests, until a solution was found to the problem of the crews of merchant ships located there. The task was entrusted to the BAP "EP Division General Agustín Gamarra'" under the command of AP frigate captain José María Silva Rodríguez. In said port the brig remained ten months.

In that period of time, '"the second armed intervention of a foreign naval force on US soil in the history of that nation occurred." It turns out that on land, a great disorder had been generated that the Californian authorities could not contain; So they decided to ask for help from the Peruvian warship that was in the port. Its commander, Silva Rodríguez, upon such a request, decided to disembark with part of the armed sailors, to place themselves under the orders of the local authorities. The US authorities together with the Peruvian naval force from the warship stranded in the port, finally managed to restore public order in the city of San Francisco.

20th and 21st century

The Chilean Manuel Antonio Román pointed out in his Dictionary of Chilenismos y de otras locutiones viciosas (1901) that pisco was a highly esteemed brandy that is manufactured in Peru, and also in Chile, and already known throughout the world. It began without a doubt, in the Peruvian port of Pisco, and that is why it took that name".

Rodolfo Lenz points out, in turn, in his "Etymological Dictionary of Chilean voices derived from indigenous American languages" (1905), that pisco was a "good grape brandy; the best in Chile is made in Huasco and in other places in the north", and when explaining its etymology he indicates that "the current pisco used to be called "aguardiente de Pisco" because he came from there and from Ica & # 34;. In the same way, José Toribio Medina in his work & # 34; Chilenismos. Lexicographic notes" (1928), indicates that this was a "aguardiente made from muscatel grapes of that origin [from the town of Pisco, in Peru] and under whose name it is also manufactured in Chile" and that it was also the "jug itself in which it is packaged".

The Dictionary of the Spanish language of the Royal Spanish Academy, in its twenty-second edition, defines Pisco as "aguardiente de uva", indicating in the etymological note & #34;from Pisco, a Peruvian city in the department of Ica". While the Encyclopedia Britannica defines Pisco as "city, Ica, southwestern Peru...known for its brandy made from muscatel grapes".

In Peru, in 1964, Law No. 15,222, on new alcohol tax rates, states that "The Executive Branch, following a report from the National Institute of Technical Standards, will establish the conditions to which the elaboration of grape spirits must be subject so that their manufacturers may have the right to use the denomination "Pisco", alone or followed by the respective specific brand, with an express indication of the place of elaboration& #34;.

In 1974, when Augusto Pinochet visited Peru, Juan Velasco Alvarado gave the former a bottle of Demonio de los Andes pisco as a present.

In 1990, the term "Pisco" It was declared a Peruvian denomination of origin, through Directorial Resolution No. 072087-DIPI, of the ITINTEC Industrial Property Directorate. The following year, with Supreme Decree No. 001-91-ICTI/IND of January 16, 1991, the territory for the production of pisco in Peru was officially established, in the coastal zone of the departments of Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua and the valleys of Locumba, Sama and Caplina in the department of Tacna.

The level of production of pisco, from the middle of the XIX century, gradually decreased during the XX, up to 11,500 cultivated hectares in 2002, due to lack of incentives and substitution of crops for other more profitable ones in the short term. Having verified the decline of this crop and wanting to gradually recover the previous levels of production, at the beginning of 2003, the Peruvian Government decided to promote the increase in cultivation areas and its export, dictating special measures to meet this objective.

Notwithstanding the foregoing, the consumption of pisco has formed part of the cultural activity in Peru, which is exposed in a chronicle by the writer Mario Vargas Llosa, contained in "El parque Salazar", published in 2007: "On Saturday night there used to be parties, to celebrate a birthday. They were benign parties as could not be, where they ate cakes and pastries, and drank soft drinks, but never ever a drop of alcohol. For this reason, when one began to feel big, before entering the party on Saturday, one would have a "captain" in the Chinese on the corner, a small glass of pisco mixed with vermouth, which inflamed the blood and excited the brains".

Designation of origin

Peruvian Pisco Legislation

Supreme Decree No. 001-91-ICTI/IND of January 1991, officially recognizes pisco as a Peruvian denomination of origin, for products obtained by the distillation of wines derived from the fermentation of fresh grapes, in the coast of the departments of Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua and the valleys of Locumba, Sama and Caplina in the department of Tacna. This means that any grape spirit prepared outside the established boundaries will be just that, a grape spirit but not pisco from Peru.

This denomination of origin granted by INDECOPI, requires producers to submit samples to certification laboratories, to submit them to a physical-chemical analysis that will determine if they meet the requirements established in the Technical Standard. This is an important requirement, since the designation of origin guarantees the consumer that the pisco they are buying has a certified quality.

according to what is specified by the Peruvian Technical Standard of November 6, 2002 (NTP211.001:2002) pisco is defined as the "Liquor obtained exclusively by distillation of fresh musts of pisco grapes (Quebranta, Negra Corriente, Mollar, Italia, Muscatel, Albilla, Torontel and Uvina) recently fermented, using methods that maintain the traditional principle of quality established in recognized production areas". Said standard also establishes that the alcoholic degree by volume of pisco can vary between 38 and 48 degrees.

International controversy over appellation of origin

About the designation of origin Pisco, there is a dispute between Chile and Peru. While Peru considers that the word "Pisco" applied to liquor has a close relationship with the geographical space where it is produced (as in the case of Champagne in France and which Spain can only produce under the name of cava) and therefore should be used only for liquor produced in Peru, Chile considers that the term or denomination is generic (as in the case of wine or whiskey) and can be used by both countries.

Chile maintains that "Pisco" It is a denomination used for a type of alcoholic beverage made from grapes. It does not deny that such a product could have been first manufactured in Peru, but argues that this name was used to designate the grape brandy produced in both countries due to various factors (packaging, export port, etc.). It also bases its livelihood on the existence of a wine-growing geographical area, in two regions of Chile, legally delimited to use the term "pisco": Atacama and Coquimbo.

Peru, for its part, bases its support on historical documents on the origin of the word pisco, pisku or pisko, applied to hunter-gatherer human settlements, called piskos, to the antiquity of the term and to the multitude of applications of this term to "bird", to "valley", to a "river", to a port, to a pre-Hispanic town, to liquor, to a vessel and also to a city; product of the denomination of the town through 20 centuries. That is: the argument begins from the etymological point of view, to culminate arguing a historical path to reach the place name. Keep in mind that the jugs where they were processed have the shape of pisqo (referring to the phallic shape of the container).

International recognition of Peruvian pisco

Within the framework of the Andean community in 1998, Bolivia, through a resolution of the Industrial Property Office, and Ecuador, through a resolution of the National Directorate of Industrial Property, recognized Peru with the denomination of origin "Pisco& #3. 4;. Colombia, for its part, did so by resolution of the Superintendence of Industry and Commerce in 1999.

In 1998, Venezuela, by resolution of the Autonomous Service of Intellectual Property, and Panama, through a resolution of the General Directorate of the Registry of Industrial Property of the Ministry of Commerce and Industries, granted Peru recognition of the designation of origin "Pisco". In the same way, Guatemala, by final resolutions of the Industrial Property Registry of 1998, and Nicaragua, by resolution of the Ministry of Development, Industry and Commerce of 1999, recognized the denomination of origin "Pisco" as Peruvian.

Costa Rica included in 1999, in its Registry of Intellectual Property of the Ministry of Justice and Grace, the appellation of origin "Pisco" in favor of Peru. In turn, Cuba, by virtue of the Agreement on mutual recognition of protection of their appellations of origin, signed between both countries in the year 2000, recognizes the appellation of origin "Pisco" to Peru.

El Salvador, by resolution of the National Registry Center, and the Dominican Republic, by resolution and certificate of Denomination of Origin of September 2004, of the National Office of Industrial Property, recognized the denomination of origin "Pisco& #3. 4; as Peruvian. However, on July 3, 2007, the Intellectual Property Directorate of El Salvador, resolving an appeal to a first instance decision of 2006, also recognized Chile's appellation of origin "Pisco", based on the Free Trade Agreement signed between Chile and Central America that entered into force in 2002. The Peruvian government challenged this decision and continued with the dispute for many years, until the final ruling was announced on October 13, 2013. of the Supreme Court of Justice of El Salvador, which recognized the denomination of origin "Pisco" exclusively to Peru.

In May 2005, Peru filed an application for international registration of said appellation of origin in accordance with the Lisbon System, before the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), which then grouped twenty-five countries (Algeria, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Congo, Costa Rica, Cuba, France, Gabon, Georgia, Haiti, Hungary, Iran, Israel, Italy, Mexico, Nicaragua, Peru, Portugal, Moldova, Korea, Czech Republic, Serbia and Montenegro, Slovakia, Togo and Tunisia).

In August 2006 the result of this application was known. Of the aforementioned States, Bulgaria —it had initially rejected it due to a previous national recognition of the term, which was not related to this grape spirit: «P.I.C. Co", which he later rectified -, Slovakia, France Hungary, Italy, Portugal, and the Czech Republic rejected the application for exclusive registration of the Pisco appellation of origin submitted by Peru, solely because it would mean an obstacle for its use of the designation of origin Pisco for products originating in Chile ("La protection de l'appellation d'origine PISCO est refusée uniquement en ce qu'elle ferait obstacle à l&# 39;utilisation pour des produits originares du Chili de l'appellation PISCO protegée conformément à l'Accord établissant une association between the Communauté Européenne et ses Etats membres, d'une part, et la République du Chili, d& #39;autre part"), by virtue of the Economic Association Agreement that Chile has with the European Union. In turn, Mexico also denied it "only if it constitutes an obstacle to the use of products from Chile with the name Pisco", protected by the Free Trade Agreement between Chile and Mexico. Iran rejected the registration because it is an alcoholic beverage, the consumption of which is prohibited under its legislation. Meanwhile, the states of Algeria, Burkina Faso, DRC, Cuba, Georgia, Haiti, Israel, Nicaragua, North Korea, Republic of Moldova, Serbia, Togo and Tunisia, therefore, in accordance with the provisions of the Lisbon Agreement, exclusively recognize the name "Pisco" to Peru.

On October 3, 2005, the Department of Intellectual Property of the Kingdom of Thailand included in its register of geographical indications, the name "Pisco" as Peruvian. In the second semester of 2006, the Patent Office of the State of Israel issued in favor of Peru the registration certificate for the appellation of origin "Pisco". Meanwhile, on October 20, In 2006, the Honduran Industrial Property Registry recognized Peru's designation of origin "Pisco".

The United States, in the Peru-United States Trade Promotion Agreement, signed in 2006 and in force since 2009, recognizes "Pisco Peru" as a distinctive product of Peru.

On May 23, 2007, the National Intellectual Property Office of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam granted recognition of the appellation of origin "Pisco" in the name of Peru. In turn, the Republic of Laos, by virtue of the Agreement for Cooperation and Protection of Intellectual Property, signed on August 28, 2007 with Peru and which has not yet entered into force, recognizes the name of origin of the "Pisco" as Peruvian.

The Administrative Registry Court of Costa Rica, on September 22, 2007, confirmed for Peru the denomination of origin "Pisco", revoking a denial of partial protection issued on July 13, 2006, in under the Free Trade Agreement signed between said country and Chile.

Singapore recognized the designation of origin of "Pisco" as proper to Peru in the Free Trade Agreement, signed with that country on May 29, 2008, as agreed after the end of the negotiations for its preparation, on August 29, 2007.

On November 3, 2009, the Intellectual Property Corporation of Malaysia registered the appellation of origin "Pisco" in favor of Peru and no other country may use it in Malaysia. Indonesia, through its Ministry of Justice and Human Rights, recognized on July 1, 2010, the designation of origin "Pisco" in favor of Peru.

On October 31, 2013, the European Union, through the European Commission –and following a request submitted by the Republic of Peru in 2009–, recognized "Pisco" as a geographical indication of Peru, without prejudice to the use of the denomination for products originating in Chile under the Association Agreement between the European Union and Chile of 2002.

Peruvian pisco production

Crafting

The elaboration of Peruvian pisco is a sector dominated by the medium-sized industry, often artisanal. This takes care of the old production processes and quality, and often does not respond to strictly commercial purposes but to a kind of generational pride. It is a flagship product of Peru.

Its quality, product of the fermentation of fresh juice of special grapes (wine) distilled in copper stills, came to have great prominence and prestige during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, not only in the territory Peru, but also outside of it, reaching European countries and the United States of America (California).

The production is governed by the Peruvian Technical Standard of November 6, 2002 (NTP211.001:2002), which in its definitions specifies the following: "Pisco is the product obtained from the distillation of the wines resulting from the exclusive fermentation of ripe grapes following the traditional practices established in the production areas previously recognized and classified as such by the corresponding official body".

The elaboration of the pisco of Peru begins in March of each year, with the collection of carefully selected grapes, coming from the vineyards of the Peruvian coast, in trucks full of baskets of this fruit. After weighing, the grapes are unloaded in a lagar, a rectangular masonry pool, necessarily located in the highest place in the winery, since from there the juices and musts will flow by gravity, first to the fermentation vats and then to the same still. Seven kilos of grapes produce a liter of pisco in this country.

The "tread on the grapes" It usually starts at sunset, avoiding the exhausting heat of the day, and lasts until dawn. A gang of six "stompers" or threshers spread the grapes evenly in the press. Between songs and jokes, the threshers do their work claiming the "chinguerito", which will accompany them throughout the night. The chinguerito is a punch made with the same fresh grape juice that is being obtained, to which is added a good dose of pisco, lemon, cloves and cinnamon.

When the sixth threshing is finished, the gate of the press opens and the fresh grape juice falls into the puntaya. There it is macerated for 24 hours. The juice is then carried to the fermentation vats through an ingenious system of gutters. Currently, the wineries use sticks, destemmers and pneumatic presses, converting the artisanal pressing process into a highly efficient mechanized system.

In the vats there is a biochemical process of alcoholic fermentation where the glucose from the natural sugar of the grapes is transformed into pyruvic acid, forming an ester. This last molecule loses carbon dioxide by expelling by a biological mechanism, characteristic of yeasts, the carboxyl functional group of pyruvic acid. The acetaldehyde formed later accepts two protons from NADH and from the one released in the initial stage of glycolysis, transforming it into ethanol or alcohol for human consumption. The vats are usually made of concrete or stainless steel, cooled by cold water that circulates through "jackets" on the tank walls.

To achieve this, small natural yeasts contained in the peel of the fruit digest one gram of sugar and convert it into half a gram of alcohol and half a gram of carbon dioxide. The process takes seven days. The producer controls that the fermentation does not stop and that the temperatures of the must do not rise excessively, since the fruit would lose its natural aroma, which is what gives the final character of the pisco. Once the fermentation is finished, it is taken again through gutters to the alembic to start the distillation.

The technique and art of distillation consists of regulating the external input of energy (heat), to achieve a slow and constant rhythm, which allows the appearance of the desired aromatic components at the right time. The process takes place in two phases: the vaporization of the volatile elements of the musts, and the condensation of the vapors produced.

In Peru three types of stills are used:

- The guy. charentès (used in the area of Coñac, France) known in Peruvian territory as "simple environment". It has four parts: the paila where the must is placed, the capitel or throat in the form of onion, swan neck where the alcoholic vapors flow, and the serpent (Immersed in a "sock" of cement with fresh water), where the alcoholic steam is condensed, becoming pisco.

- The second distillation device is equal to the previous one but also has a heats wines, luck of cylinder crossed inside by a small snake, continuation of swan neck.

- The third guy is the skirt craftsman built of brick and mud with walls lined with concrete with lime. Instead of swan neck the vapors go to the serpent through a copper tube called barrelIt's coming from a side of the vault.

There is a serious debate among the piscos about the benefits of one and the other, but it is considered that an artisan pisco, made in a falca, is a very high quality product and is highly appreciated.

Peruvian pisco is made from pure grape juice and is totally different from grape spirits made in other parts of the world. Johnny Schuler, in History of Pisco, says that: "Peru is the only producer that uses the juice and must, since all the others use them to produce their wines, returning to hydrate, ferment and distill the residual matter (pomace, pomace). The Italian grappa, the Spanish pomace or the Greek tzipouro, are made with skins. Here lies the character of the pisco of Peru. Its aromatic structure and its complexity in the mouth. Characteristics that differentiate it from the other grape spirits in the world".

The Technical Standard establishes that the distillate must rest in innocuous containers that do not change "neither the flavor nor the color", for a period of at least three months, after which it can be bottled.

- Varieties of pisquera grapes

- Aromatics: Albilla, Italy, Moscatel and Torontel.

- Not aromatic: Mollar, Black current, Quebrata and Uvina.

Varieties of Peruvian pisco

Depending on the grapes used in its production and the distillation process, recognized by the Peruvian Technical Standard, there are four varieties of pisco from Peru:

- Pisco Purospecial for its fine distillation and a single variety of grapes. It is obtained both from grapes of the varieties not aromatic as they are: broken, molar and black, as of aromatic like Italy, torontel, albilla, and flytel. Pure pisco in tasting is a pisco of very little aromatic structure in the nose, that is, in the smell. This allows the drinker not to sature or get tired of its tasteful sensations. It has a complexity of flavors in the mouth. It is the favorite of the iqueños and the pisco used for the elaboration of the pisco sour. In a recent study it has been reported that among the Peruvian consumer the purest consumption pisco is the one produced with a broken grape, which is preferred by 40%

- Pisco Mosto Verde, from the distillation of incompletely fermented fresh musts. It is made with musts that have not finished its fermentation process. In other words, the must is distilled before all sugar has been converted into alcohol. That is why it requires a greater amount of grapes per litre of pisco, which slightly increases the product. The green must is a subtle pisco, elegant, fine and with a lot of body. It has a varied aroma structure and flavors, and also a touch sensation in the mouth. The fact of distilling the must with residual sugar does not imply that the pisco is sweet. Glucose is not eliminated by alambique as it only evaporates alcohols. However, this small amount of sweet in the must conveys a very particular characteristic by providing "body" to its structure and a "velvety" sensation in the mouth.

- Pisco Accholado, Provenient of the mixture of different grape or fish varieties. Made with an assembly of several strains. The definition of "acholate" means "analogía" with the term ♪, which in the "coloquial" and "love" sense means "mezcla de races oriundas de los Andes del Perú. approaches theblended" (mixture) as it is blended Scotch whisky, cognac or sherry. For better understanding it can be established that pure and aromatic fish are "varies" or "single malt"and the chimneys, "blended". The chins combine the odor structure of the aromatic with the flavors of the pure. Each producer secretly treasures the proportions he uses in his wicker, thus creating a world of varieties and flavors. The pisco chipped as the raw material of the pisco sour, is especially appreciated according to the understood ones.

- Aromatic Piscomade of aromatic pisqueras grapes. It is made with strains of varieties aromatic: Italy, flyer, torontel, albilla. In tasting the aromatic fishes provide the nose with a range of aromas of flowers and fruits, confirmed in the mouth with a complex and interesting aromatic structure, which also provides a prolonged retro nasal sensation. They are ideal piscos, in cocktails, to prepare chilcano of pisco, whose base must be an aromatic pisco. The aromatic pisco Italy (made of grapes of the same name) would have 20% of the Peruvian market and would have greater preference in the female segment according to a recent study

Finally, there are two types of pisco that are not yet contemplated in the technical standards:

- Pisco aromatizedmade in the traditional way but aromatized, that is, they are incorporated aroma of other fruits, at the time of distillation. For this, the producer places a basket inside the paila with the chosen fruit. The basket hangs from the capital base. It is the vapours that when passing through the basket extract the aromas of the fruit. In the market there are lemon, cherry, mandarin and other flavors.

- Piscos macerated, are prepared with pisco as a macerating element and fruit as a macerated element. Of very easy preparation, these macerates are usually made at home being very appreciated digestives. For your preparation just take a wide-mouthed ladyjuana, place the preferred fruit, add pure pisco and let macerate a few weeks. People in Peru use their imagination for this type of preparation, adding orange peel, some honey, cinnamon, some raisins and what the imagination suggests.

Features

According to the Peruvian Technical Standard applied by the Ministry of Production, the production of pisco must have five invariably rigid characteristics:

- Primary: one of the main differences in the types of pisco, lies in the inputs used for its elaboration, whether artisanal or industrial. It is not only used varieties of aromatic grapes type flytel and grapes (injury of Peru), but also non-aromatic varieties such as ordinary black and molar, although in a lower percentage.

- No steam rectification: the process of distillation, is done in uncontinuous and non-continuous alambiques or malfunctions. This prevents the elimination of the constituent elements of the true pisco, by rectifying the vapors produced at the time of its distillation.

- Time of fermentation of the musts and the process of distillation: pisco comes from the distillation of "fresco" broths or musts, recently fermented. This fast procedure prevents the fermented grape broth or must, from having a long time before being distilled.

- In Peru, companies that produce pisco must conform to the requirements established for the use of alambiques; by the Technical Standards Monitoring Commission, Metrology, Quality Control and Para-arance Restrictions of the National Institute for the Defence of Competition and the Protection of Intellectual Property (INDECOPI).

- It doesn't have aggregates.: the process of distillation of the Peruvian pisco is not paralyzed until the time when an average alcoholic level of 42 or 43°GL has been obtained (approximately in physical concentration units, a 42− − 43% % VV{displaystyle 42-43%{begin}{matrix}{frac {V}{V}{V}}{matrix}}}}{matrix}}}). Nor is it used distilled or treated water, which would make you lose body, color and all the other features that distinguish it.

- Obtaining alcohol content: At the beginning of the process of distillation of the fresh musts, its alcoholic wealth reaches about 75°GL. As the process continues, the alcoholic degree decreases, allowing the integration of the other characteristic elements of the pisco.

- This process will continue until the alcoholic level has dropped to 42 or 43 degrees on average according to the fisherman's criterion; it can even reach 38°GL.

Pisco quality: cordon and rose

The quality test that distinguishes Peruvian pisco is known as "cordón y rosa". It consists of shaking the unopened bottle and then appreciating a large number of bubbles spinning at the top of the bottle, like a whirlwind, called "pink". At its ends, a tail of bubbles called a "cord" appears. Physical effect rarely appreciated in commercial piscos.

Production area

In the Peruvian territory, the coast of the regions of Lima, Ica, to which the valley of Pisco, Arequipa, Moquegua belongs, as well as the valleys of Caplina, Locumba and Sama de la Tacna region.

Implanted area

In the middle of the XIX century in Peru, around 150,000 hectares of vines were planted for the production of pisco. This area gradually decreased until it reached 11,500 cultivated hectares in 2002, due to lack of incentives and substitution of crops for other more profitable ones in the short term.

Having verified the decline of this crop, which has been practiced for four and a half centuries, and wanting to gradually recover the previous levels of production, at the beginning of 2003, the Peruvian Government decided to promote the increase in cultivation areas and their export, dictating special measures to meet this objective.

At the same time, specific and strict legal provisions were issued so that producers achieve a high level of quality, disqualifying those who do not meet the essential requirements required to obtain a first-class distillate, even preventing them from exporting it labeled as pisco.

The planted hectares produce 800,000 liters of pisco per year (statements by Ismael Benavides, General Manager of Interbank and producer of Huamaní pisco, in the newspaper "Expreso", edition of July 23, 2006). The proven result so far is that the level of harvest area has increased substantially and will probably continue to be so in the future, which would facilitate the promotion of pisco sour.

Exports

In 2007 the main export destinations for Pisco from Peru were: Chile (31%), the United States (30%), France, Spain, Germany, Canada, Colombia, Mexico, Argentina, Australia, the Czech Republic.

In 2008, Peru established itself as the leading exporter of pisco.

Promotion of Peruvian pisco

Cultural heritage

The National Institute of Culture of Peru, by Chief Resolution No. 179 of April 7, 1988, declares the term "pisco" as the nation's cultural heritage.

Pisco and Pisco Sour Day

The fourth Sunday of July was established as Pisco Day in Peru, by Ministerial Resolution No. 055-99-ITINCI/DM of May 6, 1999.

The Pisco Sour Day has also been institutionalized, which is celebrated on the first Saturday of February, as dictated by Ministerial Resolution No. 161-2004-PRODUCE of April 22, 2004.

Pisco route in Peru

In most wineries in Peru, tourism has been incorporated into their production and it is an obligatory step to visit a winery on scheduled tourist tours; where in addition to tasting the pisco, you can share knowledge, experiences and anecdotes with the hosts. They show the traveler their vineyards, their wineries, their stills and their piscos. The following are some routes of the pisco of Peru, instituted from the year 2004:

- Lima. Given the urban growth of Lima, the wineries have their shops in the city center. These are located in the districts of Pueblo Libre, Surco and Pachacámac.

- Cañete. Wineries can be found in the Santa Cruz de Flores district in the Mala valley, and in the districts of San Luis de Cañete, San Vicente de Cañete, Imperial, New Imperial in the lower part of the Cañete River Valley. One of the most important vineyards in the area is that of the winery "Santiago Queirolo".

- Lunahuaná. In the annex to Socsi, before the bridge over the Cañete River, it has rocks that have obtained gold medals at national events. The Jita annex is popular for its pisco Italy; at the top of the valley, in Catapalla, a wide variety of macerates and fish are produced.

- Zúñiga. In the annex to Cascajal, whose lands surpass the Cañete River, its fish of the Uvina variety have obtained gold medal at international events (Concours Mondial de Bruxelles 2011).

- Chincha. The whole Chincha valley produces wines and fish. One case that deserves to be highlighted is that of the winery "Tabernero", whose dyes are exported to the United States of America and whose wines and fishes have been awarded gold and silver medals at wine festivals in Paris, France.

- Ica. The Centro de Innovación Tecnológica Vitivinícola (CITE-VID), is responsible in the department of Ica for providing new technologies and monitoring quality, both in the driving of vineyards, and in the elaboration of piscos and wines. Ica is the most important producer valley and the wineries that can be visited are counted by dozens. Some of the most important iqueñas wineries are "Ocucaje", "Tacama", "Vista Alegre"The Caravedo", (the latter is one of the oldest producers of pisco and one of the oldest vineyards in South America, with 323 years of existence) among others.

- Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna. The producers of this area, thanks to the climatic conditions, produce piscos Italy and green must. One of the best known wineries is the "Omo" winery that produces the pisco "Biondi"; in Moquegua, there is one of the wineries that are already relics of the past coming to the centuryXXI. In Ilo, pisco is also produced. In the valley of Vitor, there are also rocks like in the Majes valley where a Viticulture Research Centre has also been installed. Finally in Tacna, pisco is produced in Magollo and other places in the department.

Bottle and glass of Peruvian pisco

Consumers of pisco in Peru, have built for centuries, a paraphernalia around its consumption, where it is most noticeable, is in the pisco areas such as Lima, Ica, Arequipa, Moquegua and Tacna, having spread to the rest of the territory in recent years, and which consists of normalizing both the bottle that contains it and the glass in which it should be drunk. In the producing areas, custom dictates that pisco "must be taken pure", perhaps accompanied by a ceviche or chicharrón de chancho (as is customary in Ica) and this is done to be considered a "good fisherman".

The pisco fishermen from these areas have thought of everything, to recreate not only senses such as smell and taste, but in recent years the pisco has a new standardized container, to recreate the sight. The pisco producers have reached an agreement with the National Society of Industries to package the pisco in a type of bottle, very fine and tall, 750 ml, very slender and tall, which has the characteristics of good quality engraved in bas-relief. pisco from Peru It only differentiates the different types of pisco, the label that shows the type, brand and place of origin and the prizes won.

In 2006, the Austrian house Riedel, which has been working with glass for 250 years (founded in 1756), designed the Riedel glass for pisco from Peru. The presentation of the cup was held on May 11 in the city of Vienna, within the framework of the Summit of the European Union and Latin America, having initially manufactured 40,000 units for import into Peru. Its market launch took place on June 24, 2006. On July 24, 2006, a presentation ceremony for the Riedel pisco glass was held at the Government Palace in Lima with the assistance of the President of the Republic, Alejandro Toledo, and Riedel Chairman Georg Riedel.

The design took a year of work and 29 prototypes were tested; Prominent Peruvian tasters participated in this test who analyzed the prototypes from the point of view of the characteristics of Peruvian pisco. Padelis Paliouras, representative of the Riedel House for Latin America, and Johnny Schuler have said that "Design obeys not only aesthetics, but mainly physics. Its structure allows the best of pisco to come out".

Most known cocktails with Peruvian pisco

Punch of the Liberators

It is a tradition in the Congress of the Republic of Peru, since 1821, to toast in the parliamentary compound after each transmission of the Supreme Command, on July 28, the day of the independence of Peru, with the "Ponche of the Liberators". This cocktail originates from India. It arrived in Peru, probably at the beginning of the XIX century, and was offered for the first time, already mixed with pisco, after swearing the independence in the Cabildo of Lima.

This traditional cocktail incorporates in its ingredients: 1 ounce of pisco, 1 ounce of white rum, 1 ounce of golden rum, ½ ounce of algarrobina, 1½ ounce of dark beer, 1½ ounce of evaporated milk, 1 egg and 2 ounces gum syrup.

Its preparation consists of boiling all the ingredients except the egg, letting it warm and blending the whole with the incorporated egg. It is served in hot drink glasses, decorated with cinnamon.

Pisco sours

The pisco sour is considered the most traditional cocktail prepared based on pisco, receiving the consideration of Peruvian national drink.

According to the classic recipe, it consists of 3 ounces of pisco, 1 ounce of lemon juice, 1 ounce of syrup, 1 egg white, 6 ice cubes and 2 drops of Angostura bitters.

The preparation consists of beating the ice in a shaker with the pisco, the lemon, the syrup and the egg white until the hit of the ice is not heard. Using a blender, beat for a minute and only at the end add the egg white, giving a blender stroke of no more than 4 seconds.

To serve, we recommend taking care to fill the glass up to half, trying not to get too much foam, serving with two drops of Angostura bitters.

Pisco Chilcano

The chilcano is a traditional Peruvian drink that is prepared based on pisco, preferably with soft drinks, although you can also mix it with cola or other flavored soft drinks, such as since 1935, the Peruvian Inca Kola.

Pisco punch

The pisco punch (translated as "pisco punch or slap") is a cocktail created at the end of the century XIX in San Francisco, United States of America, by Duncan Nicol. This drink was prepared with pisco which was imported by North American merchants who brought it to San Francisco from the ports of Peru. Its preparation consists of a mixture of pisco, pineapple, lemon juice, sugar, gum arabic and distilled water.

Captain

The captain is prepared by mixing an ounce of pisco, an ounce of vermouth and accompanying the preparation with two green olives.

Canary

The canario is made by mixing two ounces of pisco, orange juice to taste and accompanying with ice.

Sun and shadow

It is a popular drink in the bars of Lima but whose offer has declined due to the drop in the production of the cherry liqueur. Take two ounces of cherry, two ounces of pisco, ginger ale, ice and lemon drops to the taste.

Panther Milk

It is a mixture of leche de tigre with pisco and ají limo.

Peruvian pisco pairing

Pisco from Peru, due to its high alcohol content, cannot accompany meals as if it were a 12-14 proof wine. For this reason, it is often preferred to use it as an aperitif or downer, either pure or in a pisco sour, before or after a meal. However, pairings are possible and pleasant, although the pisco should be consumed in moderation during the meal.

It is considered that the ideal pairing for pisco is cebiche, since Peruvian pisco has a minimum alcohol content of 43°, it needs a "main course" as is the cebiche, which incorporates among its ingredients fish, onion, parsley, coriander, kion, green lemon and rocoto chili pepper, the latter two very strong that will be complemented by the high alcohol content of Peruvian pisco.

Piscos from Peru, unlike wines, generally look good if combined with acidic, strong and spicy flavors. For this reason, the pairing for pisco includes everything from olives and salty canchita to cebiches, ocopas and tortillas with avocado guacamole. A product that also combines with pisco from Peru is chili. Dishes made with fish and shellfish from the Mar de Grau or with products from the Peruvian Andes, such as potatoes and corn, pleasantly blend flavors, colors, smells, and texture. All the piqueos that pair with the pisco of Peru are part of the gastronomy of Peru.

It is also customary to accompany the pisco with the following piqueos:

- Birds: chicken wings with blue cheese sauce.

- Cars: Anticuchos of heart, loin jumped, sprouts of meat.

- Saucers: sausages with mustard, grilled sausages, morcilla, cabanosi and others.

- Grains: orange, choclo in cheese sauce, mote sancochado.

- Fish: chubby, octopus to olive, fish chicharrón, pejerrey enrollado, choritos a la chalaca, lomo salted anchoveta, anchovies, among other fish.

- Cheese: Water or soda biscuits with strong cheeses and spicy blue cheese, Tilsic cheese from the Yura valley (Arequipa), Cajamarca steaks or fresh cheeses from Arequipa or the Mantaro valley (Junín), among others.

- Tube: potato in the oven, sausageed potatoes with aji.

- Vegetables: arequipeño scribe, pichanga and onions encurtidas.

International Awards

- 2007

- In the Brussels World Competition (Concours Mondial de Bruxelles) of 2007, one of the most prestigious worldwide, of a total of 63 samples of different varieties and brands, the Peruvian pisco obtained a total of 16 medals: a Grand Gold Medal, 8 gold medals and 7 silver.

- In the wine contest Les Citadelles du Vin In France, on June 18, 2007, three pisco brands in Peru were awarded, obtaining a Citadelles trophy (equivalent to a gold medal, having been granted 96), and two Prestige trophies (the bronze medals of 191).

- 2008

- In the contest Vinalies Internationalesorganized by the Union of Enologists of France, in Paris, from February 29 to March 4, 2008, the piscos “Finca Redondo Acholado Puro” and “Finca Redondo Mosto Verde Puro” produced by the wineries Viña Vieja and Viña Santa Isabel, obtained gold medals.

- In the 2008 Brussels World Contest, the Peruvian pisco won a total of 12 medals: 3 gold medals ("Tabernero Pisco Italy Style La Botija 2007", "Tabernero Pisco Quebranta La Botija 2007" and "Viñas de Oro Pisco Mosto Verde Torontel 2007") and 9 silver.

- 2009

- In the 2009 Brussels World Contest, the Peruvian pisco won a total of 15 medals: 4 gold medals ("Pisco Acholado Don Saturnino 2008", "Pisco Barsol Acholado", "Pisco Moscatel de Viejo Tonel 2008" and "Viñas de Oro Mosto Verde Torontel") and 11 silver.

- 2010

- In the 2010 Brussels World Contest, the Peruvian pisco won a total of 7 medals: 4 gold medals ("Bianca Pisco Acholado 2009", "Casa de Piedra Pisco Italia", "La Botija Pisco Puro de Quebranta 2009" and "Pisco Italia Viejo Tonel 2009") and 3 silver.

- 2011

- In the contest Vinalies International 2011, the pisco Viejo Tonel won gold medals for its pisco Italy harvested in 2010 and silver medal for the same year's pisco.

- In the 2011 Brussels World Competition, the Peruvian pisco won a total of 11 medals: 6 gold medals ("Pisco Cascajal", "Pisco Portón Mosto Verde Quebranta", "Pisco Portón Puro Torontel", "Pisco Pozo Santo Acholado", "Tabernero Pisco Premium Mosto Verde Italia" and "Pisco Puro de Quebranta".

- In the 2011 International Wine and Splendid Competition, held in Seville, Spain, the Pisco Mosto Verde Torontel de Ocucaje won the CINVE Award 2011, maximum distinction of the event

- 2012

- Gold Medal:

- Gold Medal:

- Silver Medal:

- 2013

- Gold Medal: Pisco 4 Fundos 2012.

- Gold Medal: Pisco Don Santiago Torontel Mosto Verde, Pisco Son of the Sun Italy, Pisco Son of the Sun Quebranta, Pisco Puro Torontel Gold Ways 2011.

- Silver Medal: Pisco Carbajal Mosto Verde Italy, Pisco Finca Rotondo Acholado 2012, Pisco Finca Rotondo Quebranta 2012, Pisco Queirolo Uva Quebranta, Pisco Torontel Viejo Tonel 2012, Pisco Porton Mosto Verde Quebranta, Tabernero Verde Pisco Italy 2012, Tabernero Pisco Acholado 2012, Tabernero Pisco Premium Mosto Verde

- 2014

- Gold Medal: Cuneo Pisco Mosto Verde Italy 2013, Pisco Mosto Verde Quebranta Finca Redondo, Pisco Torontel Viejo Tonel 2013.

- Gold Medal:

- Silver Medal:

- 2015

- Gold Medal: The Sarcay of Azpitia - Pure Pisco of Torontel 2013 and Tabernero Pisco Italy the Botija 2014.

- Gold Medal:

- Silver Medal:

- 2016

- Gold Medal: Pisco Portón Monto Verde Acholado 2014

- Gold Medal:

- Silver Medal:

Contenido relacionado

Chamorro language

Kirk hammett

Cartoon in Argentina