Pio Baroja

Pío Baroja y Nessi (San Sebastián, December 28, 1872-Madrid, October 30, 1956) was a Spanish writer of the generation of '98. Baroja, who received his doctorate in medicine, he ended up abandoning this profession in favor of literature, an activity in which he cultivated the novel and, to a much lesser extent, the theater. In his work, in which he often betrays a pessimistic attitude, he embodied his individualism. His political thought, not exempt from ambiguities, went through sympathies for the anarchism of his youth, opposition to the Second Republic and defense of a military dictatorship, never abandoning his anticlericalism.

Biography

Family

He was the grandson of the printer and publisher Pío Baroja, and the son of José Mauricio Serafín Baroja Zornoza and Andrea Carmen Francisca Nessi Goñi, of Italian origin. He was the brother of the writers Carmen Baroja and Ricardo Baroja and uncle of the anthropologist, historian, linguist, folklorist and essayist Julio Caro Baroja and of the film and television director and screenwriter Pío Caro Baroja. great uncle of Carmen and Pío Caro-Baroja Jaureguialzo, the latter found and published a novel by his great-uncle, Los caprichos de la suerte , 65 years after his death.

Pío Baroja grew up in a wealthy family in San Sebastián, related to journalism and the printing business. His paternal great-grandfather, Rafael Baroja from Alava, was an apothecary who went to live in Oyarzun and printed the newspaper La Papeleta de Oyarzun and other texts (proclamations, proclamations, primers and ordinances of French and Spanish). during the War of Independence. There he married the sister of another pharmacist named Arrieta and, helped by his children, moved the printing press to San Sebastián and also edited El Liberal Guipuzcoano and some issues of La Gaceta de Bayona directed by the famous journalist and writer Sebastián de Miñano from France.

His paternal grandfather of the same name, Pío Baroja, apart from helping his father edit the newspaper El Liberal Guipuzcoano (1820-1823) in San Sebastián during the Liberal Triennium, printed the History of the French Revolution by Thiers in twelve volumes with a translation by the aforementioned Sebastián de Miñano y Bedoya. He and his brother Ignacio Ramón continued with the printing business and a son of the latter, Ricardo, the novelist's uncle, would eventually be editor and factotum of the San Sebastian newspaper El Urumea .

Pío Baroja's mother, Andrea Carmen Francisca Nessi Goñi, was born in Madrid (1849) and descended from a Lombard Italian family originally from the city of Como, on the shores of the lake of the same name, the Nessi, to whom the writer owes his second last name. Due to the sudden death of his father, his mother went to educate him in San Sebastián with his great-uncle Justo Goñi, and this maternal branch of the Goñi was linked to navigation, something that influenced Baroja's subsequent narrative, for example in his second tetralogy novel, The Sea.

The father, José Mauricio Serafín Baroja Zornoza, was a mining engineer at the service of the State; A restless man with liberal ideas, he occasionally worked as a journalist and his position as a mining engineer led his family to constant changes of residence throughout Spain. His first paternal surname, Baroja, comes from the name of the homonymous Álava village (quoted as Barolha in 1025, and located in the current municipality of Peñacerrada), of uncertain etymology, although it may contain the Eusqueric element ol(h)a 'cabana', 'shanty'. In Memorias de él , Don Pío himself ventures a possible etymology of the surname, according to which "Baroja" would be an apheresis of ibar hotza , which in Basque means &# 'cold valley' or 'cold river'. Although it could also be a contraction of the Castilian surname Bar(barr)oja.

Baroja was the third of four brothers: Darío, who was born in Riotinto and died, still young, in 1894 of consumption; Ricardo, who in the future would also be a writer and an important engraver, known above all for his splendid etchings, and Pío, the younger brother, who would leave his profession as a doctor for that of a novelist around 1896. Already temporarily separated from them, he was born the last sister: Carmen, who was to be the inseparable companion of the novelist and the wife of her brother's future editor, Rafael Caro Raggio, also an occasional writer. It is possible that a fifth brother, César, was born and that he died at a very young age.The close relationship with his brothers was maintained until the end of his days.

Childhood

Baroja was born in the city of San Sebastián on December 28, 1872 (Day of the Holy Innocents) at the sixth number of Oquendo street. It was the house that his paternal grandmother Concepción Zornoza built. At birth he became the third of three brothers, taking Dario three years older and Ricardo two. Due to the bombardment of San Sebastián due to the siege that the Carlists had erected around them (described by Miguel de Unamuno in his novel Peace in War), the family changed their address to a chalet in the shell walk. But in 1879 they all moved to Madrid when Baroja was barely seven years old, to Fuencarral street and near the Mico era, between the Bilbao and Quevedo roundabouts, a space that marked his childhood in Madrid. His father worked at the Instituto Geográfico y Estadístico de Madrid and in a couple of years he changed his address again to the neighboring street of Espiritu Santo. Baroja was able to contemplate during this period the Madrid characters of the time: the water carriers of Asturian origin, the soldiers who filled the streets from the war in Cuba, the porters, various travelers...

At that time, the father frequented the coffee gatherings that proliferated around the Puerta del Sol and some of the writers and poets of the time were invited to the house on Calle del Espíritu Santo. But a new destination for the father forced the family to move to Pamplona, in Navarra. Baroja and Ricardo had to adjust to a new Institute; Darío, the eldest, was less aware of the changes. Ricardo then began to show interest in painting and Pío became a voracious reader, not just of contemporary literature, but of serials and youth classics such as Robert Louis Stevenson, Jules Verne, Thomas Mayne-Reid and Daniel Defoe. In 1884 his younger sister Carmen was born, when Pío was twelve years old. The fact is important: Baroja pointed out that his "sentimental background" was formed between the ages of 12 and 22. A woman among three older boys. Certainly, the Pamplona period left its mark on him because grandfather Justo Goñi opened an inn on the floor of the same building where the family lived, so he was able to see bullfighters, puppet companies, singers, writers pass through the premises... A variegated and heterogeneous human landscape reminiscent of the overcrowded novels that he would write. The atmosphere of Pamplona at the end of the XIX century gave abundant adventures to the members of the Baroja family, as well as to the adolescence of peep.

Serafin's taste for itinerancy led him once again to accept a position in Bilbao, but the bulk of the family returned to Madrid in 1886 through the intercession of his mother, tired of so many moves. The maternal argument put forward was that the children could carry out their future university studies there in the capital. Serafín, his father, would periodically visit Madrid to see his family and San Sebastián to cultivate childhood friendships. In this second stage in Madrid, the family resided in a mansion owned by Mrs. Juana Nessi, wife of the Aragonese businessman Matías Lacasa, on Misericordia street, next to the Descalzas Reales Monastery, which was a "chaplains' mansion". The street where they lived, thanks to the hospitality of Juana Nessi, had only one number and was close to Puerta del Sol and the now-defunct Teatro de Capellanes (also called Comic Theater) and the Hospital de la Mercy. The Madrid home of the Barojas was in this period right in the middle of the thriving Madrid society of the late XIX century. Baroja would return to this house on Calle Capellanes years later, during his prolific period as a writer.

Dario and Pío began to go to a preparatory academy for admission to the newly founded Polytechnic School. Baroja finished high school at the San Isidro Institute, where he met Pedro Riudavets, with whom he had long conversations that Pío later included in The Adventures of Silvestre Paradox. After taking the high school exam, Pío decided to study medicine by starting the corresponding preparatory course. Until the last moment he was undecided whether to study medicine or pharmacy. In the final exams he passed all the subjects except chemistry.

During the summers, to escape the heat of Madrid, the family used to meet in San Sebastián and Baroja managed to pass the subject in September that he needed to enter the faculty. The family moved to Atocha street, near the San Carlos College of Surgery when his father was notified of the transfer to Madrid again. During this period, Pío began to attend gatherings in cafes and lead a certain social life, meeting with writers and artists at the home of his friend Carlos Venero. This environment managed to excite Baroja's writing essence. Some of these friends would be future classmates from the San Carlos faculty.

Academic training

As a medical student he did not stand out, more due to a lack of interest than talent, and by then a hypercritical and dissatisfied character was appreciated; no profession attracted him, only writing did not dislike him. During his internship at the Hospital of San Juan de Dios, San Carlos and the General, he discovered his indifference to the health profession. It is during this study period that he begins to write short stories. The meetings at Carlos Venero's house prompted his first writings and he began to sketch two of his future novels: Camino de perfección and Las aventuras de Silvestre Paradox .

In the fourth year of his degree, he had José de Letamendi and Benito Hernando y Espinosa as professors in San Carlos, and he had the bad luck of not being liked by any of them. Public clashes in the classes were frequent and both professors dedicated themselves to hindering his career. Pío Baroja will then offer a picturesque panorama of these problems and of the decadent Madrid university life in the first chapters of his partly autobiographical novel El árbol de la ciencia. In these, the father was offered a position in Valencia that again forced the entire family to relocate. However, the brothers were able to continue their careers in the new city, even when Baroja left Madrid with low spirits due to his run-ins with the two teachers. First, they settled in Cirilo Amorós street, somewhat distant from the center of Valencia, which they solved with a new move to the narrow Navellós street, next to the Cathedral itself. Unfortunately, Dario began to show symptoms of tuberculosis, something that caused the consternation of the whole family and deeply affected the writer, as reflected in his novel The Tree of Knowledge, in which Dario appears under the name of the consumptive brother of the protagonist Andrés Hurtado, Luisito.

Pío continued his medical studies in Valencia, but one of his professors during this new period, Enrique Slocker de la Rosa, a disciple of Letamendi, failed him in the subject of General Pathology. Pío frequently goes to the General University Hospital and focuses his work on completing his studies as soon as possible. However, although he passed the theoretical subjects, the professors ironically scolded him in the exams for his little dedication to praxis. He finally graduated in Valencia, but went to Madrid to obtain his doctorate by the fastest means possible. During this period he began his journalistic career writing articles in La Unión Liberal (1st phase 1889-1890) of San Sebastián, as well as in some Madrid newspapers such as La Justicia . His brother Darío died during the Christmas holidays of 1894 and melancholy and grief made the family move to a house in Burjasot to escape from the city, a house that Pío would later describe in The Tree of Knowledge.

Baroja focused on his doctorate in order not to prolong his studies and finally presented the title of his thesis in 1896: El dolor, estudio de psicofisica. The thesis was defended before a court of teachers from San Carlos. He returns to Valencia and there he finds out about a vacancy for a rural doctor in Cestona in Guipúzcoa. Although in his memoirs Baroja claims to have been the only suitor, City Hall records indicate that there was another candidate named Diego. Knowledge of Basque was a necessary requirement that could have influenced the decision.

Baroja began to practice medicine as a spur doctor. His sister Carmen and her mother moved to Cestona when Baroja settled in a large house. There Baroja moved to the farmhouses in a charioteer, with little rest. The life of a rural doctor was painful and very poorly paid. An event will change his life: his father is appointed Chief of Mines of the province of Guipúzcoa, with residence in San Sebastián. Baroja abandoned the Plaza de Cestona definitively, leaving behind a reputation (rightly or not) as a problematic person. He had some difference of criteria with the old doctor, with the mayor, with the parish priest and with the Catholic sector of the town, which gave him he accused of working on Sundays in his garden and of not going to mass, since, in effect, he was an agnostic; he never sympathized with the Church from his very childhood, as he tells in one of his autobiographies, Youth, egomania . After a scant year of medical activity, Baroja obtained a place in Zarauz, but finally gave up.

Literary career

After his interrupted experience as a rural doctor, he decides to return to the bustling Madrid; His brother Ricardo ran a bakery (Viena Capellanes) that his maternal aunt Juana Nessi had bequeathed to them after the death of her husband and Ricardo had written to him from Madrid that he was fed up and wanted to quit the business. Baroja decided to take it upon himself to run the tahona near the Descalzas Reales monastery, the family's old home (near the Celenque square). They made jokes about Baroja's employment situation that he did not like: "He is a writer with a lot of love, Baroja" — Rubén Darío told a journalist of him. To which the writer replied: "Dario is also a writer with a lot of pen: you can tell that he is an Indian."

Installed in Madrid, he began to collaborate in newspapers and magazines, sympathizing with anarchist social doctrines, but without openly militating in any. Like his contemporary Miguel de Unamuno, he abhorred Basque nationalism, against which he wrote his satire Momentum catastrophicum .

Baroja's intervention in the Viena Capellanes bakery attracted the hatred of Matías Lacasa's relatives. Added to this were the problems with the bakery workers, the fight with the union. All this atmosphere meant that dedicating himself to the bakery was not one of the happiest businesses in Baroja. In spite of everything, during this period in the bakery, working in the bakery, he meets the curious characters that would feed some of his novels (Silvestre Paradox, and the trilogy The Struggle for Life ). Those were times when news of the Spanish-American war was found on the street, something that unleashed conflicting passions. Baroja reads avidly during the long hours at the counter. During the summer months, Pío would go to see the plays that were performed in the gardens of the Retiro park in Madrid. Once his mother and sister Carmen return to see de Baroja in Madrid, shortly after his return, aunt Juana Nessi dies. The Barojas settle in the house and permanently close the Capellanes bakery. This stay in Madrid coincides with the rise of modernism and with a more or less picturesque literary bohemia.

The fondness for literature that arose in his adolescence is now increased in the long stays behind the bakery counter, in which he avidly reads German philosophy, from Immanuel Kant to Arthur Schopenhauer, finally opting for pessimism from the last batch. His educated Swiss friend, the translator and Hispanist Paul Schmitz, would later introduce him to Nietzsche's philosophy. Baroja was thus getting closer and closer to the literary world. He forged a special friendship with the anarchist José Martínez Ruiz, better known as Azorín . He likewise cultivated the friendship of Maeztu. With him and Azorín they formed for a brief period the Group of Three. In 1898, the leader of literary circles, Luis Ruiz Contreras, visited him several times to write for the Revista Nueva, which Baroja, after writing a few articles, ended up rejecting.

Travel period

In 1899 Baroja made the first of his many trips around Europe. He went to Paris, carrying ideas for a first novel in his luggage. There he witnessed the life, customs and disturbances of the French. He attends the nightlife of the cabarets and passionately lives the events of the Dreyfus case. He also frequents the Machado brothers, especially Antonio. His figure is already defined by the features with which he will remember it in the future: trimmed beard, bald head, expressive eyes and the typical Basque beret. Upon returning to Madrid, he made frequent excursions to the Sierra de Guadarrama and the monastery of Santa María de El Paular. On one of those excursions to the Madrid mountains, he met his Swiss friend, the Hispanist, writer and translator of Friedrich Nietzsche into Spanish, Paul Schmitz, and came into contact with the ideas of the great philosopher that would pervade part of his work. At the end of 1900, he and his then friend Azorín were invited by the journalist Julio Burell, to visit Toledo, which in his novel Camino de perfección will also appear consigning the excursion to El Paular and the character of the Swiss, so important to him, under the name of Schulze, and whom he will make say the following:

- The Spaniards have solved all those metaphysical and moral problems that concern us, the North, in the background far less civilized than you. They have resolved to deny them; it is the only way to resolve them (Pius Baroja, Way of perfection, chap. XIV).

Azorín, for his part, will remember Baroja with the name Olaiz in his novel La voluntad, and will say of him that "he has instilled love for El Greco among young Castilian intellectuals". With the traveler Ciro Bayo he will also make several excursions to Extremadura and will also hike through Jutland in Denmark. His active wandering throughout Western Europe (he defined himself in Youth, egomania as a "humble and wandering man") will be reflected in his novels; only Eastern Europe was left out of his interest.

However, Spain itself did not escape his curiosity either, which he visited periodically through a large number of excursions with various relatives, friends and writers. He almost always did them accompanied by his brothers Carmen and Ricardo, but also by Ramiro de Maeztu, Azorín, Paul Schmitz and even José Ortega y Gasset on one occasion when they covered a large part of the itinerary of General Gómez in his famous expedition during the First Carlist War; Baroja will write an interesting travel book about it. All these journeys at the beginning of the XX century fertilized his novelistic creativity and coincided with his most fertile literary period: in it he was gestating, with his knowledge of environments and people, the types, environments and landscapes that will later populate his novels.

Baroja's journey through Europe and Spain also extended to the same city of Madrid where he lived for many years; Abundant reflections of his impressions remain in all of his work, but above all in the trilogy The Struggle for Life , a wide fresco of the humble and marginal environments of the capital. In fact, he was a kind of second Galdós for his knowledge of the most remote corners of the Spanish capital, although, unlike the Canarian narrator, Baroja does not experience complicity or complicity with what he reflects, but rather criticizes bitterly when he has to do so and only barely does he show his lyricism, as intense as it is scarce. Among his walking companions wearing out sidewalks (as they were called) was the most frequent Valle-Inclán, since the eldest of his friends at the time, Azorín, did not like to walk. The stops at the basement of the Fornos café on Calle de Alcalá were frequent, as was the case at the Lyon d'Or, where writers and theater actors of the time used to go.

At the beginning of the XX century (1903) he was in Tangier as a correspondent journalist for El Globo , printed in Madrid. He later traveled throughout Europe (he lived several times in Paris (1906) with his sister Carmen and there he met Corpus Barga and the bohemian Francisco Iribarne, alias "Ibarra" who sabered him mercilessly. He spent some time in London (1906), and He passed through Italy (he was in Rome in 1907), Belgium, Switzerland, Germany, Norway, the Netherlands and Denmark.In 1902 the family settled in the house on Juan Álvarez Mendizábal street in the brand new Argüelles neighborhood.The house was an old A hotel that needed numerous renovations and they lived there until their father died in 1912 and their sister Carmen married. The house was full of the cats that their mother was fond of. Since 1912 they spent their summers in Vera de Bidasoa.

First novels

In 1900 he published his first book, a collection of short stories entitled Gloomy Lives, most of them composed in Cestona about people from that region and his own experiences as a doctor. In this work, all the obsessions that he reflected in his later novels are found in germ. The book was widely read and commented on by prestigious writers such as Miguel de Unamuno, who was enthusiastic about it and wanted to meet the author; also by his friend Azorín and by Benito Pérez Galdós. He always denied the existence of the "Generation of '98" considering that its alleged components lacked the necessary affinities and similarities. In that same year he published what would be his first novel: Aizgorri's House , thus beginning his career as a writer and essayist.

As an amateur bibliophile who frequented second-hand bookstores, on the Moyano slope and the bouquinistes on the banks of the Seine in Paris, Baroja built up a library specializing in the occult, witchcraft and history of the 18th century. XIX that was installed in an old farmhouse of the XVII dilapidated (but magnificently built), which he bought in Vera de Bidasoa and restored gradually and with great taste, turning it into the famous "Itzea" farmhouse, where he spent his summers with his family, who He settled in Vera del Bidasoa, although not in the uninhabitable farmhouse at the moment, but in a rented apartment, where his father Serafín Baroja died on July 15, 1912 when the restoration works on the farmhouse had not yet begun. After the death of his father and the wedding of his brother and sister, Pío and his mother were left alone in the house.

His main contribution to literature, as he himself confesses in Desde la última vuelta del camino (his abridged memoirs, Ed. Tusquets, 2006), is observation and objective, documentary and psychological assessment of the reality that surrounded him. He was aware of being a person endowed with a special psychological acuity when it came to knowing people; His alleged misogyny is a myth, having described numerous charming female characters or without any denigration towards them, rather the contrary, he was an impartial observer of women with their virtues and defects and created endearing female characters such as Lulu in The Tree of Knowledge. In addition, in his description of the characters, certain racial prejudices derived from his reading as a doctor of the phrenological theories of Cesare Lombroso sometimes appear, with a certain anthropological touch that derived from his conversations with his own nephew, the anthropologist Julio Caro Baroja, who He was his assistant in his youth and lived for long periods in Itzea.

In his novels, he reflected an original realistic philosophy, the product of psychological and objective observation ("Seeing in what is", as Stendhal said, whom he quotes in Youth, egomania, together with Dostoevsky as one of its sources when designing psychologies), also impregnated with the deep pessimism of Arthur Schopenhauer, but who somehow preached a kind of redemption through action, along the lines of Friedrich Nietzsche: hence the adventurous and vitalists who inundate most of his novels, but also the rarest listless and disillusioned, such as Andrés Hurtado from The Tree of Science or Fernando Ossorio from Camino de perfección (mystical passion), two of his most finished novels. Outside of this, his literary world drank from the numerous readings of nineteenth-century serials and adventure books that deeply marked his youth in the bohemian and small-gender Madrid of the beginning of the century XX.

He writes about the political reality of these first years of the XX century, paying special attention to the anarchist ideas that always dot his work. Dedicated to anarchist efforts, she reads her novel Aurora Roja , belonging to The Struggle for Life . In The Cape of Storms she describes the assassination of Cardinal Juan Soldevila. In her novel The Errotacho Family she describes the euphoria of exile and paints a portrait of Francisco Ascaso.

Political activity

Baroja's political life is highly inconsistent, as are other aspects of the writer's life, but in the end an evolution towards conservatism similar to that of other authors of the so-called generation of '98 such as Azorín can be seen or Miguel de Unamuno (but not like Antonio Machado or Ramón María del Valle-Inclán). The anarchist and republican periods are located at the beginning of his trajectory, and the totalitarian ones at the end. All of them were reflected in Baroja's journalistic work. In 1933, he visited Buenaventura Durruti and other anarchist militants in the Seville prison, after which he wrote: "When he left prison he thought: -Who knows if what these men advocate instead of being utopian? of the future, be in Andalusia something ancestral and traditional!".

He managed to get out of military service in the way he tells in Youth egomaniacs. In a first stage of bohemia in Madrid, he had contact with Spanish anarchists such as Mateo Morral, who, inspired by his attack on Alfonso XIII, drew a trilogy, La raza . He likewise had contact with anarchists during his stay in London. He later aligned himself with Alejandro Lerroux's Radical Republican Party (PRR) He actively participated in electoral campaigns, giving speeches in Barcelona. Encouraged by Azorín, he made an attempt to enter politics during the general elections in Spain in 1914, appearing as a councilor in Madrid and as a deputy for Fraga, but failed. When Azorín approached Antonio Maura's party, he broke his old friendship with him. The government of the Liberal-Conservative Party of Eduardo Dato was unpleasant to him.

On September 23, 1923, the coup d'état by Primo de Rivera took place and Baroja did not seem to be interested in the event. Shortly after, he gave a conference at the Ateneo de San Sebastián in which he attacked liberal democracy, despite this, he never abandoned his anticlerical convictions. Curiously, he was co-founder on February 11, 1933 of the Association of Friends of the Soviet Union along with other non-Marxist authors such as Concha Espina and Jacinto Benavente, who later joined the Franco regime. by Ramiro Ledesma Ramos, criticizes the advent of the Second Republic.

On May 13, 1935, he was admitted to the Royal Spanish Academy; The reception ceremony for the new academic was presided over by the President of the Republic, Niceto Alcalá-Zamora. In the act, Baroja read his entrance speech, entitled & # 34; Psychological training of a writer & # 34;, lasting an hour and a quarter. After the speech, Alcalá-Zamora gave the floor to Dr. Marañón, who answered the new academic. In the end, the President of the Republic awarded Baroja the academic medal, amid cheers from the public.

On September 7, 1935, Carmen Nessi, Baroja's mother, died at her home in Vera.

In 1938, during the Civil War, Editorial Reconquista published Comunistas, judios y demas raleaa (1938), a selection of texts by Baroja not directly edited by him, claiming anti-Semitic, anti-parliamentary, anti-democratic and anti-communist, and with a prologue by Ernesto Giménez Caballero in which he called the author the "Spanish precursor of fascism". Pío Baroja published Ayer y hoy in 1939. Baroja's thought during this period is crystallized in three novels where the action takes place, in part or totally, during the Spanish civil war.

Civil War: Intermittent Exile

He preferred the climate, light, landscape and vegetation of northern Spain, which is why he chose Navarra to spend the summer in 1936. On July 22, 1936, he was arrested by Carlist forces (requetés) who were heading from Pamplona to Guipúzcoa and they detained him in the neighboring town of Santesteban; this experience scared him quite a bit. He is released from the municipal jail through the mediation of Carlos Martínez de Campos y Serrano, Duke of la Torre (years later tutor of the Prince of Spain, Don Juan Carlos). Upon returning to Vera, Baroja decides to avoid problems and go to foot to the nearby border with France. After crossing the border with France in a car, he initially settled in Saint Jean de Luz and later in Paris, at the Colegio de España de la Ciudad Universitaria, thanks to the hospitality offered to him by the director of said college, Mr. Establier (hospitality that was bitterly reproached to the director by the then ambassador of the Republic in France, Luis Araquistáin, who personally and through his wife made repeated efforts before the director Establier to expel Baroja from his lodgings, efforts that thanks to his chivalry of said director, did not give the slightest result).

Due to the steps taken by Professor Manuel García Morente, Baroja was granted a safe-conduct to access National Spain. On September 13, 1937, after a year in exile, he returned to Spain, crossing the Irún international bridge. He lives in Vera's house and is rarely seen. In January 1938, he was invited to Salamanca to be sworn in as a member of the recently created Institute of Spain and to manage the publication of newspaper articles highly critical of the Republic in general and of Republican politicians (such as the well-known "An Explanation", published in the Diario de Navarra, 1-IX-1936).

He returned to Paris, and began a series of round trips to Spain until the end of the war. As the year 1939 approached, the proximity of a confrontation was announced in Paris. He returns to Spain definitively in June 1940. That same year he returns to a post-war Madrid. In The Solitude of Pío Baroja (1953), Pío Caro recounts the life of the family in the period from 1940 to 1950.

Postwar

Somehow, his best literature ends with the war, except for the composition of his memoirs Desde la última vuelta del camino, one of the best examples of autobiography in Spanish. After the Civil War, he lived for a short time in France and later settled permanently between Madrid and Vera de Bidasoa. He continued to write and publish novels, his Memoirs (which achieved great success) and an edition of his Complete Works . He suffered some problems with censorship, which did not allow him to publish his novel about the Civil War, Miseries of War , nor its sequel, Los caprichos de la suerte . The first was published in 2006, in an edition by the writer Miguel Sánchez-Ostiz, preceded, among other titles, by Freedom from submission in 2001. He held a skeptical gathering at his home in Madrid (in in which various personalities participated, including novelists such as Camilo José Cela, Juan Benet and others).

His little hotel on Calle Mendizábal —parallel to Calle de la Princesa, near Plaza de España— was destroyed by a bomb from the insurgent faction during the Civil War, for which many valuable documents he had there were lost archived. After the war ended, he moved to Ruiz de Alarcón street, near the Stock Exchange.

All his life he was a great walker, having walked around Madrid and all its surroundings in his youth, as reflected in his trilogy The fight for life (The search, Weed and Red Dawn). In his last years he was a great walker through the Buen Retiro park in Madrid, so the statue that keeps his memory was erected there (crossing with Cuesta de Moyano and Alfonso XII). He was never married and left no children.

His sister Carmen died in 1949 and his brother Ricardo in 1953. Little by little affected by arteriosclerosis, he died in 1956 and was buried in the Civil Cemetery of Madrid (next to La Almudena) as an atheist, with great scandal official Spain, despite the pressure his nephew, the anthropologist Julio Caro Baroja, received to renounce his uncle's will. Notwithstanding this, the then Minister of National Education, Jesús Rubio García-Mina, attended the funeral in his capacity as such. His coffin was carried on the shoulders of Camilo José Cela and Miguel Pérez Ferrero, among others. Ernest Hemingway attended the funeral and John Dos Passos declared his admiration for him and his debt to the writer.

Between Pío Baroja's biographers and some relatives there are still controversies about various aspects of his personality and his work.

Works

Baroja preferably cultivated the narrative genre, but he also frequently approached essays, and more occasionally theater, lyrics (Canciones del suburbio) and biography. There is a contribution by Pío to the libretto of an operetta written by the musician Pablo Sorozábal entitled: Adiós a la bohemia (premiered at the Calderón in 1933).

Narrative work

The author himself grouped his novels, somewhat arbitrarily, into nine trilogies and two tetralogies, although it is difficult to distinguish in some of them what elements they may have in common: Basque Land, La struggle for life, The past, The sea, The race, The cities, Agonies of Our Time, The Dark Forest, Lost Youth and The Fantastic Life. Saturnales belongs in its theme to the Civil War and remained unpublished due to Franco's censorship, publishing the last two novels of the series in the XXI.

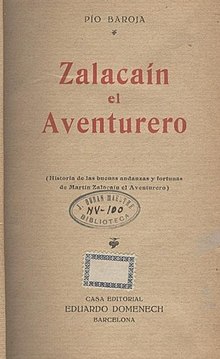

- Basque land is a tetralogy that groupes The house of Aizgorri (1900), The Elder of Labraz (1903), Zalacaín the adventurer (1908) and The legend of Jaun de Alzate (1922).

- Fantastic life is formed by Adventures, inventions and mixing of Silvestre Paradox (1901), Way of perfection (mystical passion) (1902) and Paradox king (1906).

- The struggle for life integration She's looking for her. (1904), Weed (1904) and Red light (1904).

- The past consists of The fair of the discreet (1905), The last romantics (1906) and The grotesque tragedies (1907).

- Race is formed by The errant lady (1908), The city of the fog (1909) and The Tree of Science (1911).

- Cities group to Caesar or nothing (1910); The world is craving (1912) and Perverted sensuality: loving essays of a naive man at a time of decay (1920).

- The sea is his second tetralogy: The concerns of Shanti Andía (1911); The maze of the sirens (1923); The high-rise pilots (1929) and Captain Chimista's Star (1930).

- agonies of our time collect The great whirlwind of the world (1926); The fortunes (1927) and Late love (1926).

- The dark jungle incorporate The family of Errotacho (1932); The end of the storms (1932) and The visionaries (1932).

- The lost youth Meeting Nights of the Good Retreat (1934); The Priest of Monleón (1936) and Carnival Madness (1937).

- Saturnthe last one, group to The vagabond singer (1950); Miserias de la guerra (2006) and The whims of luck (2015).

A series of novels from the last stage of the writer's life were not collected in trilogies and are often called "loose novels" because the author did not write the remaining ones due to old age and censorship (especially in which they dealt with the Civil War) mainly: Susana and the fly hunters (1938), Laura or loneliness without remedy (1939), Yesterday and today (published in Chile in 1939), The Knight of Erlaiz (1943), The Bridge of Souls (1944), The Swan Hotel (1946) and The Vagabond Singer (1950).

The Swan Hotel would be the first piece of another unfinished trilogy that would be called Días aciagos. As for Saturnales , a trilogy about the Civil War, he wrote the entire thing, but Franco's censorship prevented the publication of two of the novels that made it up; the advent of democracy made it possible for them to be printed; They are Miseries of War (2006), and The Whims of Luck (2015).

Between 1913 and 1935, the twenty-two volumes of a long historical novel appeared, Memories of a Man of Action, based on the life of one of his ancestors, the conspirator and liberal adventurer and Freemason Eugenio de Aviraneta (1792-1872), through which he reflects the most important events in Spanish history of the XIX century, from the Civil War from Independence to the regency of María Cristina, passing through the turbulent reign of Fernando VII. It constitutes a wide series of historical novels comparable to the Episodes nacionales by Benito Pérez Galdós and about the same historical period, although the Canarian writer wrote almost twice as many novels as the Basque writer and Baroja documented himself with as rigorous as Galdós himself, although his style is much more impressionistic. They are as follows: The Conspirator's Apprentice (1913), The “Brigante” Squadron (1913), The Ways of the World (1914), With the pen and with the saber (1915), which narrates the period in which Aviraneta was alderman of Aranda de Duero, Los recursos de la astucia (1915), The Adventurer's Route (1916), The Contrasts of Life (1920), The Gastizar Weathervane (1918), The Warlords of 1830 (1918), La Isabelina (1919), The Taste of Vengeance (1921), The Furies (1921), Love, Dandyism and Intrigue (1922), The Wax Figures (1924), The Ship of Fools (1925, in whose prologue he defends himself from the criticisms of his way of novelizing by José Ortega y Gasset in El Espectador), The bloody masquerades (1927), Humano Enigma (1928), The Painful Path (1928), The Bold Confidants (1930), The Sale of Mirambel (1931), Scandalous Chronicle (1 935) and From the beginning to the end (1935).

In 1938 he published Comunistas, judios y demas raleaa for the Reconquista publishing house, a book made up of fragments of Baroja's works and articles prior to 1936, but also contemporary to the Civil War, in which he was hostile to democracy and politics in general.

Baroja also published short stories, initially collected in Shady Lives (1900) and later in Basque Idylls (1902). Likewise, he was a regular in the memorial and autobiographical genre (Youth, egomania, 1917 and the eight volumes From the last turn of the road, composed by The writer according to him and according to the critics, 1944; Family, childhood and youth, 1945, End of the 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, 1946; Gallery of types of the time, 1947; Intuition and style, 1948; Reports, 1948; Autumn Trifles, 1949; and The Civil War on the Border, 2005). He also wrote a couple of biographies: Juan van Halen, the adventurous officer (1933) and Aviraneta or life of a conspirator (1931); essays such as El tablado de Arlequín (1904), La cavern del humorismo (1919), Momentum catastrophicum (against Basque nationalism), Passionate Ramblings (1924), The Lonely Hours, Intermissions. Picturesque showcase (1935), Rhapsodies. Little essays, The devil at a low price, Cities of Italy, The work of Pello Yarza and other things, Newspaper articles and some dramatic works: Brother Beltrán's Nocturnes, Everything ends well... sometimes, Harlequin, apothecary boy, Chinchín, comedian and The horrifying crime of Peñaranda del Campo.

Narrative Techniques and Style

The narrator Baroja believed art was insufficient to reflect what mattered most to him: the truth of life; His literary reflection, if he was really sincere, should arouse the same dissatisfaction that life itself caused. For this reason, like Miguel de Unamuno, he had a vivid and protean idea of what the novel was:

Is there a unique kind of novel? I don't think so. The novel, today, is a multiform, protein, in formation, in fermentation; it encompasses everything: the philosophical book, the psychological book, the adventure, the utopia, the epic; everything absolutely. To think that for such an immense variety there can be a unique mould seems to give me a proof of doctrinarism, dogmatism. If the novel was a well-defined genre, as a sonnet, it would have a well-defined technique.Pius Baroja, «Almost doctrinal prologue on the novel»

However, his structures were much less concentrated than those of the Basque philosopher and they have their own personality, a way of being like his. And in the "almost doctrinal prologue on the novel" that he put before his The Ship of Fools he responded to the ideas that José Ortega y Gasset had outlined about his narrative. His idea of the novel was open, polyphonic, permeable and fragmentary, as he considered it to flow in succession:

The novel, in general, is like the current of History: it has neither beginning nor end; it begins and ends wherever it is. Something similar happened to the epic poem. A Don Quixote and the OdysseyAl. Romancero or Pickwicktheir respective authors could add to them the same as removing chapters. Of course there are skilled people who know how to put dykes to that current of history, stop it and embalze it and make ponds like that of the Retreat. Some people like that limitation; others get tired of it, and it pisses us off.

Its composition must be heterogeneous ("the novel is a bag in which everything fits"). He made up his works as a series of scattered episodes, often linked by the presence of a central leading character in the midst of hundreds of episodic or secondary characters, or by a series of leading characters that follow one another, as in The labyrinth of the sirens. Most of the Barojan characters are misfits or anti-heroes who oppose the environment and the society in which they live, but powerless and unable to show enough energy to carry their fight far, they end up frustrated, defeated and destroyed, sometimes physically., in many others morally, and, consequently, condemned to submit to the system they have rejected. This is the case with its most famous characters: Andrés Hurtado from The Tree of Science, who commits suicide; the Fernando Ossorio of Camino de perfección , incapable of seeing that society prevails over his vain illusions; César Moncada from César o nada, who sees all his efforts as a progressive politician destroyed when he abandons the fight for just a moment to take care of himself, or Martín Zalacaín from Zalacaín the Adventurer, murdered by the rival family, the Obandos, or Manuel, the protagonist of The Struggle for Life, who finds himself thrown over and over again into the same miserable slums. As for the characterization of his characters, which Baroja calls "dolls", he opts for them to be reflected through his own actions or through the narrator's own observations, since he absolutely abhors the interior monologue:

They reproach me [...] that the psychology of Aviraneta and the other characters of mine is neither clear nor sufficient, nor leaves any trace. I don't know if my characters have value or don't have it, whether they stay in memory or not. I guess not, because there has been so much famous novelist in the nineteenth century that it has not come to leave clear and well-defined types, I will not have the claim to get what they have not achieved«Almost doctrinal prologue on the novel»

In this regard, after examining the virtues of great psychologists of characters such as Stendhal and Dostoevsky, Baroja concludes that it is impossible to create characters without incurring in contradictions, when the only thing that obsesses him is sincerity and truth: delving into the Characters always determine a propensity for pathology in the narrative, so it is not uncommon for many characters, if you delve into them, to end up appearing strange or disturbed, like many in his novels.

Barojian skepticism, his Schopenhauerian idea of a world that lacks meaning, his lack of faith in the human being lead him to reject any possible vital solution, be it religious, political or philosophical and, on the other hand, lead him to to a markedly pessimistic individualism, and not for that reason anarchic. Baroja has often been reproached for his carelessness in the way he writes. This is due to his anti-rhetorical tendency, since he rejected the long and labyrinthine periods of the long-winded narrators of realism, an attitude he shared with other contemporaries of his, as well as the desire to create what he calls a "rhetoric of a minor key", characterized by:

- Use of the short period, with little complex subordination and far from all impostation and academicism.

- Highness and expressive economy: "The writer who with less words gives a feeling is the best".

- Descriptive impressionism: selects the significant traits instead of photographically reproducing all the details as characteristic of the meticulous and documented narrators of realism.

- Tono agrio, selection of a lexicon that degrades reality tone with the pessimistic attitude of the author.

- Short essays in which the author exposes some of his ideas and intense lyric intermediates.

- Quick narrative temp, a dilated time period: the space and time of his works is little concentrated and sometimes encompasses a lifetime or even several generations, as in The maze of the sirens.

- Atomization of the novelist structure in very short chapters (probably by the influence of the novel by deliveries that he read in his youth) and with a lot of secondary characters, in a way that already announces sometimes the character or collective protagonist of later novels as The hive by Camilo José Cela.

- Dialogues respectful with orality and naturality.

- A desire for accuracy and precision, stylistic traits that confer amenity, dynamism and the sense of naturality and life that the writer intended for his novels.

Pío Baroja sometimes used a type of novel made up essentially of dialogues, as in La casa de Aizgorri, Paradox, rey and El nocturno del hermano Beltrán .

Theatrical play

Baroja's approach to the theatrical world was marked by doubts. He did not harbor much hope of being represented due to the many demands of theatrical managers. One of his first attempts corresponds to his earliest work, La casa de Aizgorri (1900). However, it seems that he was always interested in theater and everything around him since he began his life as a writer: for a while he wrote literary criticism for El Globo and even participated as a sporadic actor in some plays. of the time and in films that adapted his works. Apart from some dialogue novels from his early days, he left behind six theatrical pieces, a somewhat heterogeneous set:

- The legend of Jaun de Alzate (Basque legend on stage), 1922

- Arlequin, mouthpieceSainete

- Chinchín comedian

- The Horrific Crime of Peñaranda del Campowhich the author described as "farsa villanesca"

- The night of Brother Beltran

- Everything ends well... sometimes.concluded in 1937 in Paris.

It is also worth noting his collaboration with the cinema in the two adaptations of his novel Zalacaín el aventurero. In Francisco Camacho's late-1920s version, he himself plays the role of a Carlist. In Juan de Orduña's film from the fifties, he plays himself together with the director himself, who is going to visit him as a prologue to the story. Although he was not very fond of theater or popular shows, he adapted his play Adiós a la bohemia and composed the libretto for the homonymous small opera with music by composer Pablo Sorozábal premiered in 1933. in Madrid.

Journalistic material

Baroja was born into a family of journalists and his grandparents were printers and publishers. What's more, his father Serafín was a contributor to various newspapers in San Sebastián. His first literary works were carried out by Baroja precisely by writing small articles in newspapers and throughout his life he produced an abundant and constant creation of journalistic matter that has been the subject of in-depth studies. Baroja writes in Ahora, El Liberal, in La Justicia, in El Imparcial, all Madrid newspapers, but also in newspapers such as Mercantil Valenciano and El País and historic San Sebastian newspapers such as La Unión Liberal, La Voz de Guipúzcoa and El Pueblo Vasco. He writes for turn-of-the-century magazines such as Germinal, Revista Nueva, La Vida Literaria, Alma Española and Juventud, continuing later in Lectura y España.

At the age of seventeen he wrote about Russian literature for La Unión Liberal in San Sebastián, a newspaper of a monarchical nature. He sometimes does it using pseudonyms: "Doctor Tirteafuera" (as Dionisio Pérez Gutiérrez did), "Pío Quinto", "Juan Gualberto Nessy", etc. He was also a war correspondent. And, during his stay in Paris in the middle of the Spanish Civil War, he had to collaborate actively to earn a living and wrote for La Nación in Buenos Aires from late 1936 to mid-1940. journalist wrote articles together with his brother Darío and, after his return to Spain and already old, he collaborated in Granada Gráfica, El Norte de Castilla and Heraldo de Aragón , as well as in many others for which a certain account cannot be enough.

The first newspaper where he tried writing was El Ideal, owned by Comandante Prieto; it was a republican newspaper and he did so without signing. After this brief journalistic attempt, he went on to collaborate in La Justicia by Nicolás Salmerón. His collaborations in El Globo mark a milestone in Baroja's literary career. In 1915 he founded the magazine España , some of whose collaborators became ministers and public officials during the Second Republic.

Movie adaptations

In 1955, director Juan de Orduña adapted Zalacaín the Adventurer.

In 1966, La Busca was released, directed by Angelino Fons.

Tributes and recognitions

During his lifetime, Baroja was able to see his novels translated into other languages and his figure was already popular at the beginning of the XX century. His name was given to a series of monuments, squares, streets, schools, such as the CEIP Pío Baroja (Móstoles).

In Madrid, between Calle Alfonso XII that goes from the monument to the Fallen Angel and Cuesta de Moyano, there is a full-length bronze figure that reproduces the print of Pío Baroja, the work of Federico Coullaut-Valera. It was inaugurated by the mayor Enrique Tierno Galván on March 17, 1980 with the assistance of Baroja's nephews. On the pedestal you can read: «From Madrid to Pío». Commemorative plaques of his stay in Madrid can be found on Calle Misericordia (next to Plaza de Celenque).

Bilbao dedicates a square to his memory and gives its name to one of the tram stations that stops near it: Estación de Pío Baroja (Bilbao tram).

On May 12, 1935, he was admitted to the Royal Spanish Academy with the speech entitled The psychological formation of a writer answered by Gregorio Marañón. In it he defines himself as a street writer, with no language training; This was perhaps the only official honor accorded him. Later some academics would enter the Academy with speeches related to the work of Baroja. The centenary of his birth was celebrated at the Royal Academy of History by publishing articles in its Bulletin on the historicity of the Barojan novel.

Contenido relacionado

Gaston Suarez

Yoshito Usui

National Prize for Literature (Spain)