Philo of Alexandria

Philo of Alexandria (Greek: Φίλων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς, Philôn ho Alexandreus; Latin: Philo Judaeus, «Philo the Jew»; Hebrew: פילון האלכסנדרוני, Filôn Haleksandrôny) was a Hellenistic Jewish philosopher born around 20 BC. C. in Alexandria, where he died around 45 d. C. Contemporary at the beginning of the Christian era, he lived in Alexandria, then the great intellectual center of the Mediterranean. The city had a strong Jewish community of which Philo was one of its representatives before the Roman authorities. The abundant work of his is mainly apologetic, with the intention of demonstrating the perfect combination between the Jewish faith and the Hellenistic philosophy.

Philo was the first to think of God as the architect of the universe, unlike Plato (for whom the demiurge is a craftsman) and Aristotle (for whom the world is uncreated). In his work he attached great importance to divine Providence and grace, recognizing that the world belongs to God and not to men. So while human beings may have some spiritual kinship with God, they are not in the same rank as him. To believe otherwise would be to succumb to evil. God acts through divine powers: the one who creates, the one who orders, the one who prohibits, compassion or mercy and finally the royal or sovereign power. For Philo, there are two kinds of angels: those who helped God create the world and those who help men in their ascent to God.

In his ethics, Philo differentiated bad passions (desire, fear, sadness, and pleasure) from good ones (joy, caution, and wanting). He compared the four rivers of paradise to the four virtues of prudence (or self-control), temperance, courage, and justice. For Philo, virtuous beings are beneficial to those around them and find their own reward in righteous and virtuous actions. However, human beings are not virtuous by nature and need adapted laws, derived from natural law, to live together as best they can. Therefore, although Philo maintained (following the Stoics) that men belong to a natural community, he believed that they must be divided into nations to be viable.

Although for Philo democracy is the best form of government, he always considered it threatened by an excess of freedom or by the weakness of its leaders. Therefore, he insisted that the latter must be wise and concerned with justice and equality. Finally, although he recognizes the need for politics, he shows some mistrust towards the political figures symbolized by the person of Joseph (Jacob's son) towards whom he has ambivalent feelings.

Philo interpreted the Bible through Greek philosophy, relying mainly on Plato and the Stoics. This resulted in the following centuries in a submission of philosophy to the Scriptures. Although Philo's thought permeated the fathers of the Church, such as Origen of Alexandria, Ambrose of Milan, and Augustine of Hippo, its influence was weak in the Jewish tradition, particularly in the rabbinic tradition that arose a century or two after his death. Part of this is due to his use of the Septuagint (the Bible translated into Greek) instead of the Hebrew Bible and his allegorical interpretation of the Torah. His work also gives references to religious movements that have disappeared today, such as the therapists of Alexandria.

Philo and Alexandria

Biographical Elements

Philo belonged to a wealthy family from Alexandria: his brother Alexander held the position of alabarca, that is, a customs officer; he was very rich and close to Antonia Minor, the daughter of Mark Antony; and he lived in a luxury of which his philosopher's sister disapproved. Philo was married to a virtuous woman, but it is not known if they had children. He had a solid education, but it is not known whether he attended Greek schools or received an education at a small private establishment or even at a school near the synagogue. He is supposed to have studied philosophy by attending "public lectures at the Museum" and visiting the Library of Alexandria. His preferences drew him more toward Plato and the Presocratics than toward Aristotle and the new Academy. The descriptions of boxing, pentathlon, pancreatic contests, and chariot races that mark his writings show that he enjoyed the sport, as well as he also appreciated theatrical performances and public readings.

Although he wrote his work in Greek, historians have debated his level of proficiency in the Hebrew language. Ernest Renan considers him weak, but the debate is not over. Greeks and Jews lived in the diaspora, that is, they maintained strong ties with their cities or provinces of origin (Macedonia, Crete, Judea, etc.). If a treaty, the authenticity of which is disputed, seems to indicate that Philo made a pilgrimage to Jerusalem, his attendance at the synagogue is, on the other hand, solidly attested. However, Philo shared the opinion of the majority of the Jews of Alexandria, who "were [...] convinced of the superiority of Greek civilization", although "they did not understand the polytheism with which it was reconciled". In his writings he sometimes opposes the mythological dramas of the Greek gods to the truth of the Bible.

His writings seem to show that he did not pursue a profession for a living and devoted himself solely to studies, although according to Mireille Hadas-Lebel, "the writing of his work probably did not extend over a long period of his life", probably as he approaches old age.

Alexandria in the time of Philo

Founded by Alexander the Great, Alexandria represented for the first three centuries of its existence "the most brilliant [...] of Mediterranean civilization". Its architect Dinocrates designed it using a right-angled street network plan, first adopted in the rebuilding of Miletus and the building of the city of Piraeus in the V century BCE. by Hippodamo of Miletus. According to R. Martin, "its mathematical division responded to the mathematical and logical divisions in which these philosopher-architects sought to enclose their ideal society." After its foundation, the city became " the center of a new civilization that combined Greece and the Orient." The city was divided into five districts, two of which were occupied mainly or exclusively by Jews. The city had three types of population, corresponding to three different religions: the The Egyptians worshiped Isis and Serapis and the Greeks worshiped the gods of Olympus, while the Jews (who in Philo's time represented about a third of the population) worshiped the God of Abraham. The coexistence of these three religions gave rise to a certain syncretism, particularly observable in the necropolises.

The city had two ports. One, in Lake Mareotis, received the goods that crossed the Nile and the channels of Egypt, Africa or even Asia. The other, the seaport, was mainly used for the export of goods across the Mediterranean: Alexandria exported papyrus, cloth, vases, and wheat. A quarter of Rome's supplies came from Egypt.

Alexandria then had famous monuments such as the Lighthouse, one of the seven wonders of the ancient world, and its no less famous Library, created at the initiative of Ptolemy I Soter, who wanted to turn the city into the cultural capital of the Hellenistic world in place of Athens In 288 B.C. C., at the request of Demetrio de Falero, built the Museion (the "Palace of the Muses"), which housed a university, an academy and the Library. The latter housed 400,000 volumes in its early days, and up to 700,000 in the time of Julius Caesar. Located in the Bruchium district near the royal palaces (basileia), Epiphanius of Salamis built it. It is located in "Broucheion". The Library's assets consisted mainly of acquisitions, but also seizures. Ptolemy is said to have ordered all ships calling at Alexandria to allow the books on board to be copied and translated; the copy was returned to the ship and the original was kept in the Library.

Strabo described the institution as follows: «The Museum is part of the palace of the kings, it contains a promenade, a place furnished with seats for conferences and a large room where the scholars that make up the Museum take their meals together. This society has common income, its director is a priest, formerly appointed by the kings, now by the emperor". Among the scholars and researchers who resided in the Museum or in Alexandria, are Euclid, Archimedes of Syracuse, Nicomacheus of Gerasa (founder of arithmetic), Apollonius of Perge (geometry), Aristarchus of Samos, Hipparchus of Nicaea and Claudius Ptolemy. The two founders of the Herophilic School of Medicine, Herophilus and Erasistratus, also passed through Alexandria. The Museum also had a first-rate philological school with Zenodotus of Ephesus, Aristophanes of Byzantium and Aristarchus of Samothrace. Philosophy was always very present, especially with Theophrastus and Strato of Lampsacus, who were in the Museum. However, if from the beginning all the philosophical schools were present in Athens, the Alexandrian school of philosophy is later than Philo, who is in a way "the forerunner".

Alexandria quickly became an intellectual center of prime importance in the fields of science and philosophy, while literature was somewhat neglected. The Hellenist Alexis Pierron notes in this regard that "literature itself vegetated sadly in this atmosphere of science and erudition and only bore fruit without sap or taste".

Filon's political commitments and community

Philo was born around 20 B.C. C., ten years after Egypt became a Roman province. While this change in status had little cultural effect, it introduced profound social and political changes. The Greeks had the chance to become Roman citizens, but they had to break ties with their hometown. Jews, whom the Romans considered closer to the Egyptians than the Greeks, were required to pay laographica taxes, an obligation considered degrading. More generally, the statute than in the Ptolemaic period allowed them to form “a politeuma, a community... enjoying specific privileges, directly subservient to the government rather than the city” was called into question. The title of ethnarch (head of the community) was abolished in the year 10 or 11 AD. while the authority of the council of elders was strengthened. In addition, access to the administration and the army became more difficult for Jews because positions were reserved for Romans. Meanwhile, tension between Jews and Egyptians increased. It was in this context that Philo became politically involved in the life of the city, in particular through his work In Flaccum (Contra Flacco).

Flacus, prefect of Egypt under Tiberius, lost his support in Rome when the emperor died in AD 37. C. and was succeeded by Caligula. To stay in office, he sought compensation to reconcile the city of Alexandria by ceding to the more anti-Jewish elements. Finally Skinny, who could not maintain order, was dismissed and executed. During this period, the Jewish community suffered and was criticized in particular for its dietary restrictions. In AD 39. C., Philo was chosen along with three other notables to defend "the right of citizenship of the Jews in Alexandria." He had to face another delegation led by Apion, a Hellenized Egyptian who defended the point of view of the Greeks.It was on this occasion that Philo wrote the Legatio ad Gaium . The Jewish delegation had trouble meeting Caligula, and when they finally met with him, the emperor declared that he wanted a statue of him built as Jupiter in the Temple in Jerusalem, causing desolation among the members of the delegation. Finally, this project was not carried out thanks to the intervention of Agrippa I and the death of Caligula. Philo attributed the happy ending of both cases to Providence.

The encounter with Caligula gave Philo an opportunity to ponder the nature of tyranny. He did not believe (like Plato) that it was a degeneracy of democracy, but that it came from people naturally inclined to tyranny, a tendency that is reinforced by impunity and by the weakness of those who should end it. According to him, the desire of the emperors to be considered gods was linked to the fact that, among the Greeks, the king is the "shepherd of the peoples." He emphasized that faith in one God protects Jews from this temptation. Speaking of Caligula, Philo wrote:

He only saw the Jews wrong, precisely because they were the only ones who showed contrary provisions, educated as they were and (may be said) wrapped by their parents, their teachers, their preceptors and even more by holy laws, even also by unwritten traditions, believing in a single god, who is the father and author of the universe (Legatio ad Gaium, 115).

Philo, the Biblical Commentator

Philo and the Septuagint

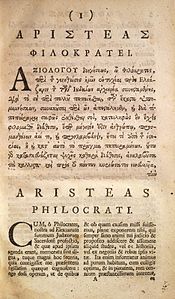

According to a tradition reported in the Letter of Aristeas (II century B.C.E. C.), a legendary pseudepigraphic description of the Greek translation of the Bible, this would have been written by 72 translators in Alexandria (c. 270 BC) at the request of Ptolemy II Philadelphus. Philo (and later Augustine of Hippo in his book The City of God) gave credence to this thesis. This translation, however, did not refer to the entire biblical text, but only to “what the Jews of Alexandria called ho nomos, the Law, or preferably, in the plural hoi nomoi”. , the Laws, that is to say the first five books of the Torah, known by the Greek name of Pentateuch".

Although in the Letter of Aristeas the role of divine providence is discreet and limited to the fact that the 72 translators finished the translation in 72 days, Philo emphasized the divine nature of this translation when specifying that the translators lived on the island of Faro, safe from the vices of the city, and had sought divine help before getting down to work. In his work On Moses (II, 37) he goes even further and affirms that the translators «prophesied, as if God had seized their spirit, not each with different words but with the same words and the same twists, each as under the dictation of an invisible blower." Therefore, for him, the Greek version is as indisputable as the Hebrew version and also has a sacred character. He further held that "whenever Chaldeans who know Greek or Greeks who know Chaldean find themselves faced with the two versions simultaneously, the Chaldean and its translation, they regard them with admiration and respect them as two sister works, or rather as one." same work". It seems that the Jews of Alexandria shared this opinion by celebrating each year the anniversary of the translation on the island of Faro in festivities in which non-Jewish Alexandrians also participated.

Summary of Philo's comments

Philo's commentaries focus on the five books of the Torah (i.e., the Pentateuch): Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy. Taking stock of the texts cited in the manuscripts of the surviving commentaries of Philo, Genesis is the most cited (58 columns) before Exodus (28 columns), Deuteronomy (13 ½ columns), Leviticus (12 columns) and Numbers (9 columns). The other biblical writings occupy only 3 columns.

Philo, following the Hebrew tradition, attributes the Pentateuch to Moses. What interests him about these books is not the history they contain (for Hadas-Lebel, Philo's thought is ahistorical), but what they say about the relationship between God and human beings. Mireille Hadas-Lebel argues that Philo wrote his Biblical commentaries based first on the questions that the Jews were raising at the time. These would be synagogal homilies that would have been collected in a more elaborate form, as well as written.

Royse, in The Cambridge Companion to Philo, distinguishes between works based on the question-and-answer technique, allegorical commentary, and works used for exposition of the Law.

| Type of interpretation | Treaties |

|---|---|

| 1. Questions and answers | Quaestiones et solutiones in Genesim and Quaestiones et solutiones in Exodum (These works have been lost in part and we only know them through a translation into Armenian). |

| 2. Allegorical interpretation | Legum Allegoriae (Allegory of laws), From Cherubim (About cherubim), De Sacrifiis Abelis et Caini (About the sacrifices of Abel and Cain), Quod deterius potiori insidiari soleat (The usual intrigues of the worst against the best), De posteritate Caini (About the future of Cain), Gigantibus (About the giants), Quod Deus sit immutabilis (God is immutable), Agriculture (On agriculture), De plantatione (On the plantation), From the crack (About the ebriedad), Sobrate (About sobriety), Confusing linguarum (About the confusion of tongues), De migratione Abrahami (About Abraham's Migration), Quis rerum divinarum heres sit (The heir to divine things), From congressu eruditonis gratia (About the meeting of the scholar with grace), De Fuga et inventione (About escape and invention), De mutatione nominum (About the name change). |

| 3. Exposition of the Act | Opposition Mundi (About the creation of the world), De somniis (About dreams), From Abraham (About Abraham; dealing with Enos, Enoch, Noah, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob, men who kept the divine law before Moses; From Josepho (About José), Of vita Mosis (About the life of Moses), Decalogo (About the Ten Commandments), Of specialibus legibus (On specific laws), From virtutibus (About virtue), De praemiis et poenis (On rewards and punishments). |

Philo's work as a commentator on the Bible has been the subject of various classifications. We can distinguish the writings where exegesis predominates, from those that resort to allegorical interpretation. In this line, Mireille Hadas-Lebel classifies the comments into three main poles: those related to the creation of the world, those that focus on the succession of generations to Moses and those who treat of the laws.

In the Tractatus Coisliniamis, a Greek inspired by Aristotle distinguishes mimetic writings (poetry) from non-mimetic ones, which are subdivided into three: historical writings, morally instructive writings, and theoretical writings. According to Kamesar, there is a correspondence between the non-mimetic genres described in the Tractatus and «the genres of the Pentateuch described by Philo: Philo's cosmological genre corresponds to the so-called theoretical; the historical/genealogical genre, to the historical; and the legislative genre, to the morally instructive one".

Philo and exegesis

In the Hellenistic period, Jews were influenced and stimulated by Greek exegesis of Homer's texts. However, these Greek texts refer to myths and were therefore not didactic; while, for Philo, the Bible is not a text that refers to myth, but constitutes the word of God. To overcome this, Philo made a double move and differentiated between a literal sense (sometimes associated with an individual's body) and an allegorical sense (associated with the spirit). While acknowledging that Philo's allegorical method is ingenious, some commentators deplore her "whimsical" side, even her occasional "wickedness".

However, Philo only resorted to the allegorical interpretation when the literal meaning was "low" or when the reading was blocked by an ambiguity of the sacred text, by intolerable absurdities for reason or even by problems of a theological nature. The same idea is found later in Augustine, for whom it is convenient to resort to allegorical exegesis for "passages of Scripture that do not refer, in their literal sense, to ethical rectitude and doctrinal truth".

The allegorical interpretation allowed in principle to reach a veiled truth. For example, Philo made the serpent the symbol of pleasure and maintained, in De Opificio Mundi, that "if it is said that the serpent emitted a human language, it is because pleasure knows how to find a thousand lawyers." Consequently, Philo refused to take literally the facts presented as real in the Bible. He pointed out, for example, that the creation could not have been made in six days, because the days are measured by the course of the sun and the sun is part of the creation. Similarly, he dismissed as "mythical" the story of Eve's creation from Adam's rib.

Philo also resorted to allegorical explanation to "explain Biblical anthropomorphisms", that is, when God is represented with human feelings. For example, when a passage from the Flood shows God repentant, Philo rejected a literal reading because, according to him, such a thought constitutes impiety, even atheism. Philo liked to repeat the words of Numbers 23:19: "God is not man." In De confusione linguarum, Philo argued that giving feelings to God is a sign of our inability “to get out of ourselves, [...] [to] get an idea of what was not created, only from our experience". Likewise, the philosopher refuses to read literally this passage that attributes a physical dimension to God: "And the glory of YHWH rested on Mount Sinai, and the cloud covered it six days; and on the seventh day he called Moses out of the midst of the cloud »( Exodus 24:16 ). In Philo's opinion, this story rather denotes the conviction that Moses had the presence of God and the spiritual communication that he had established with him.

For Philo, biblical characters represent dispositions of the soul or spirit. In this he follows Plato who, in the dialogue Alcibiades (I, 130c), defines man "as nothing more than the soul". Another Platonic feature of Philo's allegorical interpretation is the high level of abstraction of his writings. For Kamesar this is due to the fact that, for the Alexandrian exegete, the characters of the Bible are a kind of ideal archetypes that represent ideas or forms of virtue. In De Vita Mosis (1.158-9), he evokes the life of Moses in terms of paradigms and types.For Philo, Abraham symbolizes those who acquire virtue by learning; Isaac, to those who acquire it by nature; and Jacob, to those who acquire it by practice, during his fight with the angel. Cain, for his part, represents self-love. For the Alexandrian, the historical part of the Pentateuch shows us individuals who fight against their passions and their bodies, tense in an effort to overcome them and achieve virtue, in a movement of the soul that allows, through purification, to see and contemplate God.

Philo wrote his work in a similar way to the Pharisees and Essenes who were also studying the Bible at the time. Historians have no proof that they met or corresponded. However, during the same time in Jerusalem, Hillel and Shammai introduced a tradition of oral interpretation, called the "Oral Torah," which gave rise to the Talmud and Midrash. For Belkin, in a way, "Philo is the author of a Midrash in the Greek language". In fact, even if Philo's work is clearly more philosophical, there are points in common with the Midrash, in particular in the importance given to etymology and the attention paid to the smallest details of the text. Midrashic authors, however, made a more restricted use of allegory and kept "biblical characters in their human dimension".

According to Photius of Constantinople, Philo was behind the allegorical interpretation of the Bible adopted by Christians. Theodore of Mopsuestia regarded Philo as Origen of Alexandria's teacher for allegorical interpretation. However, according to him, the father of the Church goes further in this regard since, despite everything, Philo continued to adhere to the meaning of the text.

The main characteristics of his commentaries on the Pentateuch

In De Opificio Mundi, Philo wondered why Moses (whom he called, as was then common among Hellenistic Jews, ho nomothetès, the Lawgiver ) begins the five books of the Pentateuch, also called the books of the Law, after the Genesis account. He replied that it was due to the fact that "the laws were the closest image of the constitution of the universe" (Opif . 24).The reference to the laws also allowed him to assert that the text was not a mythology. According to Philo, because Moses was chosen by God and carried the laws "engraved on his soul", these were the true laws of nature, those of a God who is both creator and lawgiver of the universe. the lives of the patriarchs clearly showed that they lived according to the law (even before it was revealed on Sinai) it was because, as the Stoics might have said, they were "living laws". Two triads of patriarchs: Enos, Enoch and Noah (on the one hand) and Abraham, Isaac and Jacob (on the other), led Philo to particular developments.

Philo attributed to Enos the virtue of hope, while Enoch underwent "a conversion, a reformation" that allowed him to strive for perfection. As for Noah, as he writes in De Abrahamo, he was "beloved of God and friend of virtue". About the second triad, the episode of the oak of Mamre where Abraham welcomes three strangers in the desert can in fact be interpreted literally and means Abraham's hospitality; in the allegorical interpretation, Philo insists that the unknown is three in number. According to Mireille Hadas-Lebel, for Philo "there are three characters in one: God, 'he who is', framed by his two powers: the creative power and the royal power". When it comes to punishing Sodom, only two angels they attack because "Being stands apart." Likewise, for Philo, only four out of five cities were punished because the first four represent the senses that lead to vices, while the fifth represents sight, a symbol of height, of philosophy. Philo was also interested in the Abram's name changes to Abraham and Sarai to Sara, which he interpreted allegorically as a move towards true wisdom.

Joseph and Moses symbolize for the philosopher two ways of being a leader. He did not have a very high opinion of Joseph and criticized him for being too tempted by luxury and a social life rather than a search for the truth, although the way he resisted the charms of Potiphar's wife raised him in his esteem.. Joseph, according to Philo, was caught between the body (symbolized by Pharaoh and Egypt) and the soul (symbolized by Jacob). Moses, in En Vita Mosis, held a special place because he was the protege of God, "the interpreter of God," the lawgiver, a human and divine being. Philon wrote:

He was human, divine or composed of the two natures, for he had nothing to do with the spirit of the people, but he dominated and always tended to be greater (MosI, 27).

Philo's interpretation of the six days of creation was marked by Plato's thought expounded in the Timaeus and included "Pythagorean and/or Stoic" elements. on the sixth day she has no sex, she is "a soul, an emanation of the logos". The process of creating woman from a rib removed from Adam while he slept, while intelligence of the man is asleep, prompted him to consider the woman as the symbol of sensitivity. If paradise symbolized virtues, for Philo the tree of knowledge of good and evil symbolized prudence. The snake, meanwhile, symbolized pleasure, which appeals more to the senses (the woman, for Philo) than to intelligence. Mireille Haddas-Lebel maintains that in Philo there is no theory of original sin. Cain and Abel represent only two tendencies of man: the one that turns towards possession, the earth, and the one that turns towards God. Although Cain symbolizes evil, Philo never mentions Satan.

Comments focusing on Judaism and the Law

Cristina Termini, in The Cambridge Companion to Philo, argues that "the excellence of the Law of Moses is one of the pillars of Philo's thought". In fact, Philo's exegesis tended to to unite the law of nature and the laws of Moses, emphasizing the rationality of the commandments. His comments insisted on the three prescriptions that distinguished Jews from other populations at that time: circumcision, Shabbat, and food prohibitions.

In a way, because Antiochus IV Epiphanes forbade circumcision, it became a central element of Jewish identity. For Philo, circumcision helped prevent disease and tended to remind people that God is the true cause of procreation (De specialibus legibus, 1.8-11). It also symbolized the elimination of superfluous pleasures. Finally, it allowed internalizing the Law because "it symbolizes two fundamental principles of the Torah: the repudiation of pleasure, which is the main cause of moral errors, and faith in God, the true source of all good."

The Shabbat celebrates the birth of the world. The symbolism of the number seven is essential to understand the meaning that Philo gives to Saturday. The number seven, for him, is linked to one, and reveals something of what unites us with God. In addition, it is an imitation of God since it reminds that God rested on the seventh day. Finally, he calls us for justice and freedom as even the servant is free on that day, so the master has to do his daily chores on that day.

During the reign of Antiochus IV not only was circumcision prohibited, but Jews were also forced to eat food considered unclean, further strengthening their resolve. However, the question of the rational nature of these prohibitions remained unanswered, as the reading of the Letter of Aristeas shows. Philo, for his part, maintained that the food laws derive from the tenth commandment, which prohibits coveting another's property. He interpreted this commandment in its general sense, considering lust or desire as the leaven that leads to low passions, to what is falsely called good.

In a way, Philo returned to the Platonic tripartite division of the soul, which distinguishes the rational part, the emotional or irascible part, and the concupiscible part. According to Philo, the lawgiver Moses wanted through these laws to strengthen the virtue of "enkrateia (self-control)", necessary for good relations between individuals. Therefore, reserving the first fruits for the priests improves self-control and teaches us to see things as if they were not available to us. For him, pork and fish without scales and fins are doubly problematic: on the one hand, they encourage gluttony because of their taste, and on the other, they are harmful to health. Philon explained that the fact that it is forbidden to eat carnivorous animals and those that attack men is because humans should not be forced to eat them out of anger and a spirit of revenge. Philon explained that if the consumption of animals that chew the cud and have a forked hoof is allowed, it is because the split hoof teaches to observe and distinguish good from evil, while rumination reminds that the study involves a long work of memory and assimilation..

Philo the Philosopher

Presentation of Philo's philosophical work

Philo was eclectic on philosophical matters, borrowing from almost every school. Although heavily influenced by Plato and Aristotle, he attributes the invention of philosophy to Moses, who would later communicate his wisdom to the Greeks, particularly through Pythagoras, who would have been in contact with disciples of the prophet during his travels through the Mediterranean basin.

In his philosophical work, however, Philo made few references to the Bible or Jewish teachings. According to Royse, his writings bear witness to Philo's gifts but also to a certain eclecticism to the extent that they sometimes take the form of theses, diatribes or dialogues.These texts are the ones that have suffered the most over time. In fact, as they were of lesser interest to scholars, monks, and Christian researchers, their preservation was somewhat neglected.

Because of this eclecticism, so-called "philosophical" works are sometimes considered as compilations that form "a mass of rather crude extracts juxtaposed in a purely mechanical way". Mireille Hadas-Lebel recalls that the works of which Many times we have only fragments of the original works and he wonders if criticism has not been "unjustly severe towards a work that has the merit of reflecting well the philosophical culture of an age, nothing less than the philosophical writings of Cicero, which find more indulgence".

| Treaties | Ideas developed |

|---|---|

| Quod omnis probus liber sit | Book focused on the stoic idea that freedom is, first of all, interior. |

| From aeternitae mundi | For a long time, doubts were made clear about the authenticity of this book. Today the specialists consider that it is a work of Philo, although it seems that the second part of the original work has been lost. |

| Of providentity | The concept of divine Providence appears for the first time between the Stoics and Crisipo of Solos. It was assumed almost at the same time by Phil and Seneca. The concept was criticized by the aristotelians, the epicures and the new Academy. |

| Of animalibus | This book holds, following the stoic and against the new Academy, that human beings have a special position in the world, because they are the only ones with God who have a Logos or a reason. |

Philo, the magicians, the Essenes and the therapists

About the magicians (the followers of Zoroaster) and the Indian gymnosophists (the naked sages), Philo writes in his Quod omnis probus liber sit (74):

Among the Persians, it is the kind of magicians that searches the works of nature to know the truth and that in silence, through manifestations that are clearer than the word, they receive and transmit the revelation of the divine virtues. Among the Indians, it is the order of the gymnosophists who, in addition to natural philosophy, also strive in the study of moral science, and thus make their whole existence a kind of lesson of virtue.

Mireille Hadas-Lebel wonders if Philo's admiration for the Indian gymnosophists was nothing more than an "intelligent concession to the times and an ingenious detour to introduce the most indisputable model of virtue, that offered by the Essenes". Philo left “the two oldest reports on the Essene sect. One in his treatise entitled Quod omnis probus liber sit (§§ 75-91); the other in his Apology of the Jews, a book now lost but of which Eusebius of Caesarea, in his Preparatio evangelica (book VIII chap. XI), has preserved the passage about the essenes The exact date of these two references is unknown." According to him, the Essenes lived in community and did not have any personal property, they were in favor of the equality of men and against slavery. In philosophy, they favored ethics and the acquisition of virtues. Every seventh day they attended the reading of the Torah that a teacher commented allegorically.

Therapists were close to the Essenes, but more contemplative. They left the world after a long period of active life and traveled to the desert, near Alexandria and Lake Mareotis. There, they dedicated themselves "to science and to the contemplation of nature, according to the holy prescriptions of the prophet Moses" The number 7 seemed to mark their life: they met every seven days, they had a banquet every seven weeks, etc. During this banquet they celebrated their departure from Egypt, that is, their spiritual exodus. Philo, in De Vita Contemplativa, noted that they were at the service of "the Being that is better than good, purer than the One, more primordial than the monad".

Philo and Aristotle

Philo took his theory of causality from Aristotle, as well as his conception of virtue as a mean between extremes, a position he expounds in his treatise Quod Deus immutabilis sit.

However, as a rule, Philo was opposed to Aristotle, especially regarding the creation of the world. For him, as for Plato and the Stoics, the world was created, while for Aristotle the world is eternal. However, in the Treatise on the eternity of the world it seems to say the opposite. This led scholars to consider that this text was not from Philo for a long time. However, philological and stylistic studies have confirmed the authenticity of the text. Today, researchers tend to think that the text is incomplete and reduced to exposing Aristotelian theses, while the part where it would address a more Platonic position would have disappeared.

Filo and Stoicism

It would be difficult to determine whether Philo borrowed more from Platonism or Stoicism, as both pervade his thought. Mireille Hadas-Lebel sees the Stoic influence in De Opificio, because creation is regarded as dependent on both a passive principle (matter) and an active principle (God, considered as the true creator). The way of seeing the universe as a kind of megalopolis governed by Providence is also Stoic, as developed particularly in De Providentia. Likewise, the idea of the link between Providence, the Logos that pervades the universe, and the reason of men is profoundly stoic. Following the Stoics, the megalopolis is governed by beings endowed with reason (men and women) in the moral and political part and by the stars in the physical part. Like the Stoics, Philo argues in De Animalibus that the universe was created for humans while he considered animals, which have no hands, no language, and no reason, inferior to man.

Stoicism's contribution also permeates the moral domain as shown in Quod omnis probus liber sit, where Philo developed the idea that it is the control exercised over the four passions (pain, fear, desire, pleasure) which leads to wisdom and freedom. Thus, like the Stoics, "virtue is identified with reason, with the logos that pervades the universe." Following Zeno of Citium, "wisdom consists in living according to virtue." According to Mireille Hadas-Lebel, if Philo promoted an austere virtue that denounces luxury and sexual pleasures and if he exalted "simplicity, frugality and self-control" it was also because his temperament pushed him in this direction.

Philo also borrowed from Stoicism the sevenfold division of bodily functions (the five senses, language, and the reproductive function) and the fourfold classification of nature (inorganic matter, plant world, animals, reason).

At the same time, he generally opposed the materialism of the Stoics. Ethically, he rejected the idea that man is the master of his destiny and the captain of his soul, as Horace particularly proclaimed. For him, in fact, it was blasphemy to consider the source of any faculty or virtue in oneself and not in God.

Influence of Plato and Pythagoras

Jerónimo de Estridón quickly noticed the influence of Plato's thought on Philo. The Timaeus permeates its commentaries on Genesis from De Opificio Mundi and Legum Allegoriae. In both Philo and Plato, a benevolent God, called "craftsman" by Plato and "architect" by Philo, created the world. In fact, he first created the intelligible world, the architect's plan, before the material world. In the same way, as in Plato, the architect is not responsible for the faults and evil of the real man because it was not he, but his assistants who created the sensitive man. He also took from Plato the theory of ideas, which constituted a essential part of his cosmology. As for Plato, for Philo the body is the tomb or the prison of the soul.

From ancient times, Eusebius of Caesarea and Clement of Alexandria emphasized how much Philo had been influenced by Pythagoreanism. Furthermore, being a Platonic and a Pythagorean was not contradictory, insofar as Plato's spokesman in Timaeus is a Pythagorean. Middle Platonism and Neo-Pythagoreanism, which arose at roughly the same time, shared similar characteristics.. For Philo, numbers "govern the laws of the physical world" and are the starting point for a better understanding of the world. The one, the monad, as in Pythagoras, constitutes "the essence of the divine". refers to femininity, to a divided substance. Three is a masculine number. The six (2x3) is «the perfect world that corresponds to creation». Four is the perfect number, since both 2x2 and 2+2 are four. Seven is Philo's favorite number: if, according to the Pythagoreans, it corresponds to Athena, the motherless virgin, for Philo it represents God himself. Seven also rules life and the cosmos. Eight represents beauty. Philo barely commented on the nine. Regarding ten, he considered that "the mathematical virtues of ten are infinite."

In De posteritate Caini, Philo attributed the number 10 to Noah because he belonged to the tenth generation of mankind, “a generation higher than previous generations [...] but still lower than next ten [generations], beginning with Shem, the son who fought with good works the deviation of the paternal soul, to end in Abraham, model of sublime wisdom."

Conception of philosophy

Philosophy, for Philo, is the contemplation of the world, relied on sight that stimulates thought and communicates with the soul, as shown in the following passage:

The eyes, since they leave the earth, are already in heaven at the limits of the universe, at the same time to the east, to the west, to the north and to the south; and when they do, they force the thought to turn to what they have seen to be fulfilled. Thinking, in its own way, is under the effect of a passion: it has no respite, restless and always in motion, finds in the sight the starting point of the power it has to contemplate the intelligible things, and comes to ask questions: are these phenomena unbelieved or have they had their beginning in a creation?, are they infinite or finite?, is there one or more universes? On the other hand, if the universe was created, who created it?, who is the demiurgo, in its essence and its quality, what thought it had in doing it, what does it now, what existence, what life it has? (Abr161-164).

Observing the world led to both philosophical and scientific questions. Philo wrote about this:

Exploration for these and other similar problems, what to call it in addition to philosophy? And the man who asks these questions, how to designate it with a more appropriate name than that of philosopher? For the research of God, of the world, of the animals and plants contained in this together, of the intelligible models and their sensitive realizations, of the individual qualities and defects of the produced beings, this reflection manifests a soul in love with science, passionate about contemplation and truly in love with wisdom (Spec. II, 191).

Philosophy is wisdom and prudence. Mireille Hadas-Lebel emphasizes that in Philo, «the ‹true» philosophy includes both ‹wisdom› (sophia) for the service of God, and ‹prudence› (phronesis). >) for the conduct of human life" (Praem., 81). Philo held in De Congressu (79):

As the sciences that constitute the cycle of education help to understand Philosophy, Philosophy helps to acquire Wisdom. For Philosophy is the study of Wisdom. Wisdom is the science of divine and human things and their causes.

Two paths lead to wisdom: philosophy and Jewish laws and institutions. "What the best-tested philosophy teaches its followers, the laws and institutions have taught the Jews: the knowledge of the highest and most ancient Cause of all, which has saved them from the error of believing in begotten gods" (De Virtute, 65).

The question that arises is whether Philo was the first to make philosophy a slave to Scripture and theology, the idea that dominated the West until the late XVII. For Harry Austryn Wolfson, the answer is yes; for Mireille Hadas-Lebel, the hypothesis deserves at least to be examined because, according to her, the fundamental originality of Philo's work comes from "the articulation of philosophy with Scripture".

Philo, Philosophy and the Scriptures

The God of the Scriptures and the God of the Philosophers

Two ways to know God

For Philo, there are two ways to know God: abstract philosophy and revelation. We can know God by observing the world and the cosmos, about which he wrote: «the first philosophers sought how we arrived at the notion of the divine; then others, who appear to be excellent philosophers, have said that it was by the world, its parts, and its powers residing in it, that we had formed an idea of the cause [of God's existence]." The second part of the quote refers to the Stoics. For Philo, through abstract philosophy we can acquire knowledge in accordance with the conversion of our soul to God. If abstract knowledge of God is possible, it is because He is "the source and guarantor of human intelligence and autonomous philosophical knowledge". Taking the existence of the creator god for granted, Philo considered the Bible to be an infallible source.. Furthermore, when he comments on Genesis, he certainly takes inspiration from Plato and the Stoics, but he changes the order of reasoning. For him, the basis is the Bible and not abstract knowledge. For Mireille Hadas-Lebel, the originality of the Alexandrian philosopher "wants me to develop his ideas, not by themselves, but in relation to a biblical verse."

A personal God or an abstract principle of God

The question of the two ways of knowing God, by faith or by reason, leads to the question of the nature of God. For those who have faith, God is above all a personal and intimate God who "illuminates" them. For a philosopher like Aristotle, on the contrary, God is an abstract principle, the principle that sets the world in motion (the immobile prime mover). On this point, Philo seems to have hesitated: on the one hand, in relation to the absolute transcendence of God, he pointed out that "God is not man"; on the other, he pointed out that “God is like a man.” According to Roberto Radice, Philo seems to mean that God “would be like a man, although much taller in thought than him, but completely different in physical appearance from him.” ».

Divine transcendence

Aspects of God's transcendence

The fact that not even Moses saw the face of God denotes for Philo the absolute transcendence of God: He is "the first object that is better than Good and prior to the Monad". than the One" and "cannot be contemplated by anyone but himself, because it is up to him to comprehend it" (Praem., 40). Philo considered divine transcendence as a radical difference between God and his creation:

Very important is the statement of Moses. He has the courage to say that it is only God to whom I must reverence and nothing to come after Him (Ex., XX, 3) neither the earth, nor the sea, nor the rivers, nor the reality of the air, nor the variations of the winds and seasons, nor the species of plants and animals, nor the sun, nor the moon, nor the multitude of stars that circulate harmoniously, neither the sky, nor the whole world. The glory of a great soul that arises from the common is to emerge from the becoming, to transcend its limits, to adhere to the uncreated [...] according to the holy prescriptions, to which we are commanded to adhere to it (Dt., XXX, 20). And when we cling to God and serve Him tirelessly, God Himself becomes known to be shared. To promise this, I trust the word that says: The Lord Himself is His inheritance (Deut., X, 9) (Congr., 133-134).

From this quote it can be deduced that idolatry consists in considering created things as gods, one of Philo's fundamental themes, according to Jean Daniélou. Abraham's greatness comes precisely from the "blessing granted by God" (Heres, 97) that allowed him to abandon "the Chaldean science of the stars which taught that the world is not the work of God" (Heres, 97) to turn to God.

Roberto Radice also insists on the importance of divine transcendence in Philo, which he links to the fact that God in the Jewish tradition is unnamable. This idea that God has no name was already present in Pythagorean circles in the IV century BCE. C. However, with them it had a negative character in relation to the irrationality of the material world, while with Philo, the absence of a name is something positive. The thesis of the ineffability of God introduced a negative theology that marked the Neopythagoreans and Plotinus a few years later.

Divine transcendence and man

For Philo, the human mind cannot comprehend God: «The uncreated [...] resembles nothing among created things, but transcends them so completely that even the most penetrating intelligence is far from grasping it and he must confess his impotence» (Somn., I, 184). In this case, is there an irremediable separation between God and the human being? No, but the union does not depend on the possibility that the human mind conceives of God. He writes on this subject: "What is more dangerous for the soul than to attribute what it is to God by boasting?" (Cher., 77). John Chrysostom. However, despite the fact that God is not knowable by intelligence or by concepts, he is known by grace, by "the gift that God makes of himself":

Moses insatiably desires to see God and be seen by him, so he asks him to clearly show his difficult reality to understand, to change his uncertainties by a firm faith. And in his fervor, he does not loosen in his search, even knowing that he loves something difficult to achieve or even better inaccessible, yet he strives to achieve it. Then he penetrates into the darkness where God is, that is, in the hidden and unshaped notions of the Self. In fact, the cause is not in time or place, but transcends time and place [...] This is how the soul, a friend of God, when seeking what is Being in its essence, comes to an invisible and formless search. And it is from there that the greatest good comes to him, namely to understand that the Being of God is incomprehensible to any creature and to see that even he is invisible (Post., 13-15).

The Logos

God, the Logos and the world

Regarding the Logos, Jean Daniélou maintains that many expressions come back to designate it. One of the most striking passages in this regard is the following:

If any man is not yet worthy to be named the son of God, to be ready to conform to his first-born Logos, the oldest of the angels, to be an archangel, and to bear several names: he is called in principle, the name of God, Logos, man in the image, seer, Israel. So, if we cannot yet be considered children of God, we can at least be considered of his report image, the Most Holy Logos. Because the very old Logos is the image of God.

Philo specialists questioned the status of the Logos: is it on the same plane as the divine or is it an intermediary between God and the world? Philo wrote about this:

It is the Archangel and the very old Logos that the Father who generated everything gave him the gift of being on the border to separate the creation of the Creator. He intercedes incessantly before the incorruptible by mortal and fragile nature and is sent by the Lord to the servant. It is not begotten as we are, but intermediate among the ends that communicate with each other (Her., 205-206).

Today the second solution dominates. It is defended by both Jean Daniélou and Roberto Radice, who consider the Logos "as a panel between the transcendent God and the sensible world".

The Logos as an instrument of creation and divine providence

The Logos is, in a way, the instrument by means of which God created the world: «The Shadow of God is his Logos, by means of which, as by an instrument, he created the world» (Laws allegorical ). and gives orders to the driver so that he directs the Universe correctly" (Fuga, 101). The principle of the Logos as an instrument of Providence is enunciated in particular as: "The Logos of God travels the world; it is what most men call fortune. He gives to some what is good for some and to all what is good for all» (Imm., 176).

The principle of division and unity of logos

The Logos has a function of division: «Indivisible are the two realities, that of the judgment in us and that of the Logos above us, but being indivisible, they divide the other things in large numbers. The divine Logos has discerned and divided all things. Our Logos, all the realities and bodies that it grasps intelligibly, divides them into indefinitely indefinite parts and never stops dividing» (Heres., 234-236). On the other hand, the Logos is also a link: "the Logos of Being, being the link of the Universe, also maintains all its parts and tightens them to prevent them from coming undone and disjointed" (Fug., 112).

To express this principle of cohesion, Philo also uses the term pneuma (breath or spirit) that he finds so often in the Genesis account ("the Spirit of God moved over the face of the waters », «animals have the breath of life», etc.) as in Stoic writings. For the latter, the pneuma or breath was an emanation of the creative Logos that maintained order and harmony in the world.

The Logos and Wisdom

For Philo, Wisdom was prior to the Logos and in a way constituted its source: «Moses calls Eden the Wisdom of Being. From this Wisdom, as from a source, the divine Logos descends like a river and divides into four principles that are the virtues» (Ps., LXIV).

Creation

Creation and the world of ideas

Following the Stoic conception, God is for Philo "the active cause of creation". Likewise, although he interprets the verses of Genesis using Platonic concepts, he does not repeat the process. If Plato's demiurge creates the cosmos taking a model from a world of ideas already pre-existing because it is eternal and uncreated (Timeo, 31), Philo's God first creates the world of ideas and then the world. From this it follows, according to Roberto Radice, that God can really, in the Alexandrian philosopher, be called an architect to the extent that he also created the plan of the world.

If it is necessary to speak in clear terms, I would say that Cosmos noêtos It is nothing but the Logos of God creating the world, as the intelligible city is nothing but the thought of the architect meditating on the creation of the city (Op25).

For Philo, the intelligible world was created on the first day. "The Creator named the necessary measure of time: day, not the first day, but a single day, so called because of the unity of the intelligible world that has a nature" (Op., 29-31); then came the sensible world: «The incorporeal world had from now on its borders constituted in the divine Logos. The sensible world was brought to its fullness on its model" (Op., 36).

The Man

In Genesis 1:26, God says, "Let us make man in our image, after our likeness"; whereas in Genesis 2:7, man is formed from the dust of the ground. This led Philo to emphasize the difference “between the man fashioned now and the man who was created in the image of God before. Indeed, the model is sensitive, has qualities, is composed of body and soul, male or female, mortal by nature. But what has been made to the image is an idea, a gender, a seal, intelligible, incorporeal, neither male nor female, incorruptible by nature» (Op., 134-135).

This leads Philo to distinguish two elements in man: the physical and the intellectual. For him, the intellect is hierarchically above the corporeal and in relation to the divine, through the image of God, but this relationship remains hidden from him: «The intelligence that is in each one of us is capable of knowing other things, but is incapable of knowing itself" (Leg. all., I, 91). On this same theme, he also writes: "God inspired man with his own divinity: this invisibly marked the invisible soul with his own features, so that the terrestrial region itself would not be deprived of the image of God. And this model was so invisible that the image itself remains hidden from view» (Des., 86-87).

As Jean Giblet remarks:

While, for all Greek thought, the "image" is on the side of the sensitive and visible world, it suddenly produced a revolution. The image of God Moses speaks of becomes the expression par excellence of the invisible and spiritual value of intelligence. This is because the perspective has changed: the fundamental opposition is no longer between two universes, one sensitive and another intelligible, but rather between God and the created.

Divine powers and angels

Divine powers

The powers bear witness to God's action in the world. In De posteritate Caini, Philo explained:

He (God) cannot be known face to face and with direct view, because then we would see him as he is, but he is known by the powers that follow him and accompany him. These manifest, not their essence, but their existence from their works (166-169).

In his interpretation of the episode of the oak grove of Mamre, Philo distinguished two powers: the creative power called God and the governing power called Lord.

In De Fuga, instead, he lists five divine powers: creative power, royal power, mercy, the power that commands, and the power that prohibits. These five powers are symbolized by the Ark of the Covenant:

The five powers are represented and have their image in the holy things: the laws established in the Ark are the image of the power that commands and of which it prohibits, the Ark's cover is the image of merciful power (it is called propitiative), the winged cherubims that are on each side are the image of creative power and real power (cf.Fuga100).

According to Jean Daniélou, the structure of five hierarchical powers is a constant in Philo. Man encounters first the power that prohibits, then the one that commands, then mercy, then sovereignty, and finally the Creator: "knowledge of powers or positive theology forms the little mysteries, knowledge in the darkness or negative theology constitutes the great mysteries".

In general, for Philo, the Logos is superior to the powers because it participates in creation. Returning to the symbolism of the cities of refuge, he writes: «The most ancient, the safest and the most excellent, which is not only a city but a metropolis, is the divine Logos, where it is useful to take refuge above all. The other five, as colonies, are the powers of the Legon who presides over the creative power, according to which the Creator made the world through his Logos »( Fug ., 94-95).

Angels

For Philo, angels can represent the Logos (as in De cherubim 35) or symbolize the main divine powers, which are sovereignty or goodness (as in De cherubim i> 27-8). They can also represent the thoughts and words of God (as in De confusione Linguarum 28). or as heroes who act as intermediaries between God and men. Actually, "evil angels are almost unknown" to Philo, contrary to the tradition expressed in Jewish apocalyptic accounts of the time; this is because Philo's angelology is Greek-inspired, influenced in particular by Plato and Plutarch.

Philo distinguished two types of angels: those who cooperated in the construction of the world and those who help men in their ascent to God, who can also transmit men's prayers to God. In both cases, angels are at the service of God:

The whole host of angels, set in well-ordered ranks, is presented to serve and worship the Lord, who has prepared them and those who obey as an army commander. The divine army is not allowed to be accused of desertion. It is the king's business to use his powers to do things that God must not do alone. It's not that God needs someone to do something. But seeing what suits Him and the sensing beings, he leaves certain things for the lower powers to do them (cf.Conf171).

Sin, grace and divine providence

The imperfection of the world, sin and grace

Why did God create an imperfect world? For Aristotle, this was easy to explain because God belongs solely to the world of thought. For Philo, who followed the Platonic path, it was more complicated. Inspired by the fact that, for Plato, the demiurge creates everything as perfectly as possible, he thinks that human nature, created in the image of God, cannot do anything good by itself if God does not instill his grace in it. Certainly Philo could have introduced, to explain evil, a negative principle corresponding to Platonic matter ( chöra ), but he refused to do so because that would contradict his thesis of a One God and creator of the whole world.

For him, evil, impiety or sin consist in believing oneself on the same level as God, in thinking that one possesses oneself:

There are two opposing opinions among themselves: one allows the mind everything, like the principle of feeling and touching, moving and resting; the other attributes everything to God, as he is his creator. The type of the first attitude is Cain, whose name means possession, because he believes that everything belongs to him; the type of the second is Abel, which means relation to God (From Priest., 2).

To sin, therefore, is to reject divine grace, it is to want to be like God, as is clearly observed when he distinguishes three ways of sinning (De Sacr., 54):

- Forget the blessings of God and deprive yourself of the action of grace.

- Belief for excessive pride that one is the author of his successes.

- To assert that, although the good that comes to us comes from God, we still deserve it.

The grace and harmony of the world

For Philo, to have grace is to trust in God:

Those who claim that all that is in their thinking, their sensitivity, their speech is a gift of their own spirit, profess an ungodly and atheistic opinion and are counted in the race of Cain, who not even being their own master made the claim to possess all other things. But those who do not attribute all the beauty of nature, relating it to the divine graces, are truly of a noble race (Post., 42).

To have grace is also to accept that the world belongs to God and not to men: «No mortal is in lasting possession of any good. Only God should be considered lord and master and only he can say: Everything is mine" (Cher., 83). Finally, as in Cicero and Posidonius, grace is believing in universal sympathy, in a need for the cooperation of men: «God has granted the use of all creatures to all, without making any particular being perfect, so that he does not need others. So, wanting to get what he needs, he goes to them. It is like a lyre, made of several strings: by their interchange and mixing, the various beings are led to communion and agreement, from which the perfection of the entire universe results" (Cher., 108-110).

Divine Providence

Philo insisted in many passages that God is both the one and the all. According to Roberto Radice, through his writings, Philo wants to insist on two points: the superiority of God and divine Providence. God does not reside somewhere in the universe, but, like the Stoics, is superior to the cosmos. The idea of divine Providence springing from God's absolute transcendence is clearly stated in De opificio 46: «God directs everything according to his law and justice, in any direction he wishes, without the need for anything else. Because everything is possible for God". Mireille Hadas-Lebel insists on the fact that, for Philo, divine providence not only concerns the whole, the whole, but also extends to specific individuals:

He drives the chariot of the world with the reins of Law and Justice, whose power is absolute; without limiting his providence to the most worthy beings of him, he extends it to those who have less shine (Migr. 186).

Filo and ethics

The foundations of Philo's ethics

According to Carlos Lévy, Philo «refuses to base his ethics on the dogma of oikeiosis or appropriation”, a fundamental principle of Stoicism and, more generally, of the philosophical doctrines of the Hellenistic schools. Scholars adduce several reasons to explain this rejection. In the first place, as a Jew and a Platonist, it was difficult for Philo to accept that ethics is rooted in an instinct common to men and animals. Indeed, despite the fact that the Stoics placed man above the animal and they considered him the only one who shared the logos with God, they believed that the unity of the world was achieved through the feeling of appropriation, which operates both in the human world and in that of animals.

However, for Philo, the soul is only a stranger in the body, it does not preside over a natural adjustment, an appropriation of man for himself. The notion of nature does not refer in Philo to an instinct, but it has a normative meaning: it is the expression of the divine will. Created man is, above all, a sinner who cannot be saved without the intervention of divine transcendence. What matters, therefore, is not the impulse given by instinct, but the closeness to God, since man has been created in the image of God. God's closeness to men is manifested in two ways: through the providence inherent in creation and through the effort of man who, in the search for rationality, consciously seeks to resemble God. However, it is not about to put himself in God's place, but to establish a spiritual kinship with him. For Philo, although all men can reach this spiritual level, only the Jews can reach it as a people.

The Nature of the Soul

Although he fundamentally describes the soul as endowed with a rational part and an irrational part, Philo took from Plato the tripartite structure exposed in the Timaeus and the Republic, which they present the soul as formed by reason (logos), will (thumos) and desire (epithumia).

In Quaestiones in Genesim, however, he took up the tripartite division of Aristotle, who distinguished the vegetative part (threptikon), the sensitive part (aisthetikon) and the rational part (logikon).

Passions

Stoicism distinguishes four bad passions: desire (epithymia), fear (phobos), sadness (lupê) and fear. pleasure (hêdonê); and three good passions (eupatheiai): joy (chara), prudence (eulabeia) and will (boulesis). i>). Philo generally adopted the Stoic scheme of the passions while departing from it. For example, for him, joy is not (as in Stoicism) the opposite of pleasure, but refers to the state of a person who has achieved good. Likewise, hope is a "good" emotion, while the Stoics considered it negatively because it led to the passions. For Philo, "the four passions of the Stoics are the four legs of the horse, the animal that in Plato symbolizes the irrational part of the soul".

For Philo, human beings are helped in their fight against passions by the four traditional virtues (prudence, temperance, fortitude and justice), to which he adds self-control (enkrateia) and resistance (karteria). It is better not to face a passion when it reaches its peak. Therefore, he held that Rebekah symbolized prudence when she ordered Jacob to leave the house to escape Esau. Likewise, the wise man does not become wise by his own strength, but needs the help of divine grace. Apathy it is not a consequence of submission to the order of nature, but "is based on the belief that there is a transcendence that is not subject to the laws of nature." In short, Philo distinguished two types of apathy: the one that borders on indifference and the one that points to the absence of excess, to the moderation of emotions (metriopathy).

Unlike the Stoics, for whom the important thing was to live in harmony with oneself, Philo positively viewed madness of divine origin, "the possession by God of the soul of a sage."

The virtues

In his exegesis of Genesis (Genesis 2:10-14), Philo compares the four virtues: prudence (phronesis), temperance (sophrosyne), strength (andreia) and justice (dikaiosyne) with the four rivers of paradise. In De specialibus legibus, does not follow the Hellenistic tradition and presents the royal virtues, which for him are piety and holiness. Then follow three virtues (in the sense of following or serving a rich person): wisdom, temperance, and justice. Although, both in Philo and in Aristotle, virtue is never a strong passion but resides somewhere between two extremes, Carlos Lévy stresses that the philosopher's adherence "to Aristotelian ethics is only relative, his absolute adherence goes towards ascetic ethics and mystical detachment".

In De virtutibus, the two central virtues are metanoia (repentance) and eugeneia (nobility). For Philo, metanoia is not an unhappy passion as with the Stoics, but simply the sign of human finitude and openness to transcendence. The eugeneia does not reside (as in Aristotle) in lineage, filiation. Only the moderate and fair is noble. Abraham thus represents the model of nobility, because he abandoned the polytheism of his ancestors for the truth of monotheism.

Stoically inspired, self-control is assimilated to "the science that doesn't want us to go beyond what agrees with right reason" and is a variation on the theme of temperance. The Virtue of Fortitude it is inscribed in the Socratic tradition, which wants it not to be determined by anger but by knowledge. The virtue of justice has several meanings: it is submission to a religious ideal, it is also the mean, and finally (from a neo-Pythagorean perspective) a principle of equity. No one can achieve perfect virtue because it belongs only to the One, to God. Finally, Philo noted that although all virtues have feminine names, they possessed "the powers and activity of a mature man"..

Evil and Moral Progress

For Philo, evil is constantly present in this world. Thus he interpreted allegorically that in the Pentateuch the death of Cain, "a character who symbolizes the presence of evil on earth", was never shown. Philo presented the body as the seat of the passions, but did not develop (like the pessimistic versions of the platonism) the idea of a fall of the soul into the body. He did not appreciate the Epicureans, because for Philo the body should not be completely neglected and that bodily pleasure was necessary for procreation: pleasure was necessary for the fullness of the human being.

In order to live in the least imperfect way on this earth and progress towards goodness, three attitudes are possible: that of Abraham, characterized by the effort to know; Isaac's, which results from a happy nature; and that of Jacob, for the fight against what in human nature involves the senses and passion. As in the stoicism of Panaetius of Rhodes, Philo valued the person who progresses morally (pokoptön). The process had three stages: an education stage; another of progress proper, compared to the work of a man planting a tree; and finally, perfection, considered as the construction of a house. Philo did not insist on the teacher in the sense of educator (like the Stoics) since, for him, the only teacher is God and the important thing lies in the face to face with him.

Politics

Like the Stoics, Philo maintained that humans belong to a natural community (physikê Koinônia), where one of its fundamental rules is the restitution of what has been lost. As a result, there is a friendship between humans that should lead to rejecting slavery (as the Essenes did) and fighting crime. They must also be philanthropic. In a certain way, according to Carlos Lévy, Philo responded in this way to the Greeks, who accused the Jews of misanthropy. As K. Berthelot demonstrated, while for the Stoics the center of the social life of human beings resides in the love of parents for their children, for Philo (who follows the Ten Commandments) this center resides in the love of children for their parents.

Following the Stoics, Philo believed that there is a law of nature (nomos physeos) which, quoting Zeno of Citium, "orders to do what is right and prohibits actions contrary to justice" (SVF I.162). Moses is the model of the wise politician: he is not only a legislator, but also the embodiment of law (nomos empsychos). As the law of nature, the laws received from God prescribe what is good and prohibit what is bad. For Cicero, the natural law is valid only for virtuous people, the other laws need less perfect and more capable of containing the passions. Quite similarly, for Philo, the natural community is divided into nations due to the geographical dispersion of men and the passions of the human soul, which makes the peaceful coexistence of nations impossible and makes the world a virtual city. Political politicians, symbolized by José, must (therefore) make "adjustments", "additions" to the natural regime to allow men to live together imperfectly. For this reason, there is a deep mistrust of the political world in Philo, as Carlos points out. Lévy: "The ambivalence towards the character of José shows that, for Philo, immersion in the world of politics, while not necessarily leading to evil, constantly poses such a risk."

Philo considered democracy "the most civilized and most excellent of regimes" (Spec., IV, 237), because it is based on equality, a principle that governs the universe: «Because everything that leaves something to be desired here below is the work of inequality, and everything that responds to an adequate order is the work of equality: this is defined at the level of universal reality as strict cosmic harmony, at the level of the city as democracy» (Spec., IV, 237). He held therapists in high regard because they rejected slavery. In addition, Philo knew that democracy is fragile, always threatened by excessive freedom and the weakness of its leaders, which led to ochlocracy. He wrote about it:

The good (regimen) is the one who adopts democracy as his constitution, respectful of equality and whose judges are the Law and Justice; such a city is an hymn to the glory of God. The evil (regimen) is the one that degrades the good city, like the false coins or those that do not have rash depreciate the currency: it is the government of the multitude (oclocracy), which takes inequality as ideal and gives free rein to the oppression of injustice and anarchy (Confus. 108).

He does not mention the monarchy, although the texts he comments on leave him free to do so. He considered it important that Moses insist on the people's choice of leaders. For Philo, the ruler (archon) should surround himself with the wisest and most capable people, endowed with a sense of righteousness and piety. This choice must take into account the most important issues, those relating to equality and justice. In fact, the government of a democracy as understood by Philo is very much like what Plato calls the aristocracy or the rule of the best. He points out about the leader or the leader:

[...] what suits him are wise designs, well executed; we like to see him spend his wealth generously, reserved only what the forecast orders him to save, to protect himself from the uncertain blows of destiny (Legat51).

The retribution of the just

For Philo, "the price of intelligence is intelligence itself, and justice, like each of the other virtues, is its own reward" (Spec., II, 259). According to Mireille Hadas-Lebel, this position was already that of Plato, Aristotle, the Stoics and even the rabbis of the time who taught it, such as Antigonus of Socos in the I a. C.: «the good deed was in itself his own reward, just as evil was in itself his own punishment» ( Abot ., I, 3).

Philo did not use the Platonic myth of Er to introduce the idea of heaven and hell, as Christians would. He is not sensitive to the idea of the resurrection of the dead, later developed by the Pharisees. it was due to the fact that, for Philo, man is composed of body and soul and that, at the death of the human being, "the intelligent and celestial soul reaches the purest ether as towards its father" (Her., 280). According to him, there are two types of soul. The first is the one that turns to God in a disinterested way: it is the soul of the just, which will be united, like that of the patriarchs, to the people of God. This is how he interpreted the phrase "and was joined to his people" found in the Bible in the passages dealing with the death of the patriarchs ( Genesis 25: 8, 35:29, 49:33 ). For ordinary and disinterested souls, the reward was to leave "a house rich in quality and number of children" (Praem., 110). The idea of conversion was present in Philo, especially that of "those who have despised the holy laws of justice and mercy", but not linked to a messiah, but to God himself.

For Philo, virtuous men are, above all, a blessing to those around them:

Then, when I see or hear someone say that one of them is dead, I feel very sad and overwhelmed, and I weep less for them than for the living; for them, in fact, following a law of nature, has come the necessary time, yet they have had a glorious life and a glorious death; but those who are deprived of the strong and powerful hand whose support kept them sane and saved, will soon perceive,Sacrif124-125).

Filon's Influence

Influence during the period of writing of the Gospels

Philo lived in the time of Jesus. If he could have heard of Pontius Pilate, the beginnings of Christianity are completely unknown to him. In addition, there is virtually nothing known about the development of Christianity in Alexandria before the end of the centuryII, although the oldest fragment of the Gospel of John (the papyrus P{displaystyle {mathfrak {P}}}}52), dated c. 125, was found in the oasis of Fayum in Egypt. Two theses are often expressed to explain this lack of knowledge: the first Christians were either gnostics or both Jews and Christians were killed in the Kitos war in 115-117.

Folker Siegert believes he perceives an indirect influence of Philo in the Epistle to the Hebrews and in the Gospel of John written in Ephesus, where Apollos lived, a Jew from Alexandria who participated in the creation of the local Christian community. The latter, who also resided in Corinth, may also have had some influence on the letters to the Corinthians. Scholars have noted similarities between the Gospel of Luke (of Pauline inspiration) and Philo's thought. For Mireille Hadas-Lebel, as for Siegert, the influence is not direct, but results from the impregnation by the diaspora Hellenistic Jew with ideas close to those of Philo. If the notion of Logos, of the word of God, which we find in Philo, is present in the Gospel of John, the notion of incarnation in which it emerges is completely alien to it. Likewise, a connection between the Gospels and Philo in matters of Christology is not possible.

Influence on the Fathers of the Church

Clement of Alexandria was the first Church father to make extensive use of Philo's work, drawing inspiration from his commentary on the Biblical passage about Sarah and Hagar. Origen, who resided in Alexandria before going to Caesarea, owned Philo's books and made quite extensive use of them: studies have shown that his work has no less than three hundred direct, indirect or printed references to the Alexandrian philosopher. At Caesarea, Philo's work was studied by Eusebius of Caesarea, who regarded the therapists as Christians converted by Mark the Evangelist. This story marked Late Antiquity and the Middle Ages, where this community was considered the source of monasticism. In the 4th century, Philo's work marked Gregory of Nisa and Basil of Caesarea.

In the Western Christian Church, Philo profoundly marked the thought of Ambrose of Milan, who referred to his work more than 600 times. Following Ambrose, Augustine of Hippo was imbued with Philo's thought and used his work to interpret Genesis. In his book The City of God, marked by the opposition between the city of men and the city of God, he included the great opposing biblical couples Abel-Cain, Sara-Agar, Israel-Ishmael, returning to « the great allegorical style of Philo". Jerome of Estridon included Philo, Seneca and Josephus as the three famous non-Christians in his book De Viris Illustrubs .