Philip II of Spain

Philip II of Spain, called "the Prudent" (Valladolid, May 21, 1527-San Lorenzo de El Escorial, September 13, 1598), was King of Spain from January 15, 1556 until his death; from Naples and Sicily from 1554; and of Portugal and the Algarves —as Felipe I— from 1580, achieving a dynastic union that lasted sixty years. He was also King of England and Ireland iure uxoris , by his marriage to Mary I, between 1554 and 1558.

He was the son and heir of Carlos I of Spain and Isabel of Portugal, brother of María de Austria and Juana de Austria, paternal grandson of Juana I of Castilla and Felipe I of Castilla, and of Manuel I of Portugal and María from Aragon by maternal route; He died on September 13, 1598 at the age of seventy-one, in the Monastery of San Lorenzo de El Escorial, for which he was brought from Madrid in a chair-lounger made for the occasion, given the insistence of the monarch to pass his last days there.

Since his death he was presented by his defenders as an archetype of virtues, and by his enemies as an extremely fanatical and despotic person. This dichotomy between the white or pink legend and the black legend was favored by his own actions, since he refused to have his biographies published during his lifetime and ordered the destruction of his correspondence.

His reign was characterized by global exploration and territorial expansion across the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. With Philip II, the Spanish monarchy became the leading power in Europe and the Spanish Empire reached its apogee. For the first time in history, an empire integrated territories from all inhabited continents.

Prince Philip

Education

In 1534, the Empress Isabel chooses Silíceo as teacher of the still child Felipe. In 1535, Carlos V appointed don Juan de Zúñiga y Avellaneda tutor or educator of the prince, Felipe becoming educated only by men, and abandoning the company and guardianship of his mother, who had a small house or court made up mostly of women.

In 1541, Juan Calvete de Estrella replaced Silíceo as Felipe's teacher. The prince learned Latin and Greek, but was not formally taught French or Italian, languages that he could understand but never mastered, despite being the languages of many of his future subjects.

Carlos, due to his absences, could not get involved in his son's education, but in 1543, he appointed Felipe Governor of Spain, advised by three veteran advisers, participating in state affairs, a position he would hold until 1548, and whose experience helped him to train as a future monarch.

On June 30, 1546, at the age of 19, Felipe received the emancipation letter by order of his father, who renounced his parental authority; the young prince is legally of legal age.

The Most Happy Journey [1548-1551]

At the end of 1548, Felipe left Spain to go to Italy, from where he traveled to the Netherlands, leaving his cousin Maximilian along with his sister María as governors.

In 1549 the young prince will visit the seventeen provinces, where he will be sworn heir and successor to his father by the different states, in a festive atmosphere, presided over by court parties and knightly tournaments.

In 1550 he accompanied his father to Germany, where they met his uncle Ferdinand of Austria. Here Carlos will have a dispute with his brother, so that he recognizes Felipe as successor in the Empire, something that Fernando refuses.

In the summer of 1551, Felipe returned to Spain, where he would remain until 1554, once again serving as governor, while his cousin and sister went to Germany.

Monarchy Extension

Duke of Milan

After the death, on November 1, 1535, of Francis II, the last Sforza, the Duchy of Milan was left without a sovereign. The kings of France, related to the Visconti family, claimed the dukedom. This was one of the causes of the successive Italian wars. Francisco I saw in the death of the Duke of Milan a new opportunity to seize the territory, causing a third war against Carlos I of Spain, which ended with the Truce of Nice in 1538.

In 1540 the duchy was still without a sovereign, being in charge of a governor. At first, Carlos I himself thought of naming himself a duke, since Milan was a feudatory state of the Holy Roman Empire and the emperor had the power to grant the title. But this could be considered a casus belli in France, and furthermore, it would damage its image as a liberator and not a conqueror. So he decided to grant the title to Prince Philip. On October 11, 1540, Philip was invested as Duke of Milan. The ceremony was secret and the prince electors were not consulted to avoid international problems.

In 1542 a new war broke out between France and Spain. Among the conditions of the Peace of Crépy, which ended hostilities in 1544, was the wedding of Charles, Duke of Orleans and son of Francis I, to Charles I's daughter Marie of Habsburg (and the Netherlands and Franche-Comté as dowry), or with the daughter of the King of Romans Ferdinand, Anne of Habsburg (and Milan as dowry). The choice was Milan, but in 1545 the death of the Duke of Orleans rendered the agreements invalid. Prince Felipe was secretly invested duke again on July 5, 1546. In 1550 Philip's appointment was finally made public and, on February 10 of the same year, Ferrante Gonzaga, Governor of Milan, swore an oath of allegiance to him in his name and that of the city.

King of Naples

At the end of 1553 it was announced that Philip was married to his second aunt, Queen Mary I of England. But it turned out that Philip was only a prince and a duke. There could be no marriage between the queen and someone of lower rank. Carlos I solved the problem by renouncing the Kingdom of Naples in favor of his son, so that he would be king. On July 24, 1554, Juan de Figueroa, special envoy of Carlos I and regent of Naples, arrived in England with the formal investiture of Philip as King of Naples and Duke of Milan. The next day the betrothal was celebrated.

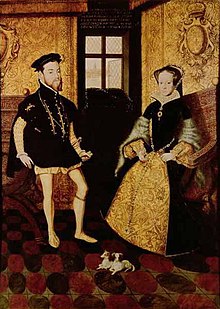

King of England and Ireland

On July 25, 1554, Philip married Queen Mary I of England. At the end of the ceremony they were proclaimed:

Philip and Mary, by the grace of God, King and Queen of England, France, Naples, Jerusalem, Ireland, Defenders of the Faith, Princes of Spain and Sicily, Archdukes of Austria, Dukes of Milan, Burgundy and Brabante, Counts of Habsburg, Flanders and Tyrol, in the first and second year of his reign.

The marriage clauses were very rigid (comparable to those of the Catholic Monarchs) to guarantee the total independence of the Kingdom of England. Philip had to respect the laws and the rights and privileges of the English people. Spain could not ask England for military or economic aid. In addition, it was expressly requested that an attempt be made to maintain peace with France. If the marriage produced a son, he would become heir to England, the Netherlands, and Burgundy. If Maria died being the minor heir, her education would be the responsibility of the English. If Philip died, Mary would receive a pension of £60,000 a year, but if Mary died first, Philip would have to leave England, relinquishing all his rights to the throne (which happened in 1558).

Philip acted in accordance with the stipulations of the marriage contract, meeting with strong resistance from courtiers and English parliamentarians, which was manifested in an abortive assassination attempt in March 1555 in Westminster., exerted a notable influence on the government of the kingdom, ordering the release of noblemen and knights imprisoned in the Tower of London for having participated in previous rebellions against Queen Mary, and acting vitally for the reintegration of England into the Catholic Church. After his departure to the Netherlands, a Selected Council of Englishmen sent letters to Felipe demanding his opinion and recommendations on the various government issues he was debating, coming to faithfully follow the guidelines that the king gave them. he sent later. During an important part of his reign he was absent, especially after 1556, when his father abdicated the Crowns of Spain in favor of him. a, Sicily and Sardinia.

On November 17, 1558, while in the Netherlands, Queen Mary I Tudor died childless. Her sister ascended the throne as Elizabeth I of England, recognized as such by the already ex-king Philip.

Sovereign of the Netherlands and Duke of Burgundy

In 1555 Carlos I, already old and tired, decided to give up more territories in favor of his son Felipe. On October 22 of the same year, Carlos abdicated in Brussels as Sovereign Grand Master of the Order of the Golden Fleece. Three days later, in a grandiose and ostentatious ceremony before dozens of guests, the abdication as sovereign of the Netherlands took place. the Habsburgs. The renunciation of the County of Burgundy took place on June 10, 1556.

Carlos thought that Spain would defend the Holy Roman Empire from those territories, weaker than France. Unlike Castile, Aragon, Naples and Sicily, the Netherlands were not part of the heritage of the Catholic Monarchs and saw the monarch as a foreign and distant king.[citation required]< /sup> The northern states soon became a great battlefield, aided by France and England, who exploited the situation of constant rebellion in Flanders to weaken the Spanish Crown.

King of Spain, Sicily and the Indies

On January 16, 1556, Carlos I, in his private rooms and without any ceremony, ceded to Felipe the Crown of the Spanish Kingdoms, Sardinia, Sicily and the Indies. Felipe was already performing government functions since 1544, after Carlos I wrote in 1543, on his return to Spain, the Instructions of Palamós, which prepared Felipe for the regency of the peninsular kingdoms until 1550 when he was still sixteen years old. Although during his youth he lived for twelve years outside of Spain in Switzerland, England, Flanders, Portugal, etc., once he became king of Spain he settled in Madrid and strengthened the role of this city as capital of all his kingdoms.

King of Portugal

On August 4, 1578, after the death without descendants of King Sebastian I of Portugal at the Battle of Alcazarquivir in Morocco, his great-uncle, Cardinal Enrique I of Portugal, inherited the throne. During his reign, Philip II became, as the son of Isabella of Portugal, a candidate for the Portuguese throne alongside Antonio, the Prior of Crato and grandson of the Portuguese King Manuel I, Catherine of Portugal and the Dukes of Savoy and Parma. Felipe received the support of the nobility and the high clergy and the Prior of Crato was supported by the vast majority of the people.

On the death of Enrique I, the Prior of Crato proclaimed himself King of Portugal on July 24, 1580. Given this fact, Philip II reacted by sending an army under the command of Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Pimentel, the Grand Duke of Alba, to fight against the Prior of Crato and claim their rights to the throne. The battle of Alcántara culminated a rapid and successful military campaign that forced Antonio to flee and take refuge in the Azores islands, from where he was evicted in 1583 after the battle of Terceira Island.

Once Lisbon had been taken, Felipe II was proclaimed King of Portugal on September 12, 1580 with the name of Felipe I of Portugal and sworn in as such by the Cortes assembled in Tomar on April 15, 1581. Portugal reigned from Madrid and appointed Fernando Álvarez de Toledo Constable of Portugal and I Viceroy of Portugal, highest positions in that country after the person of the monarch himself. Felipe II achieved the long-awaited unification of the Iberian Peninsula under a single Spanish king.

Culture and art

The government of Felipe II coincided with the historical stage known as the Renaissance, although the ideological change was not as extreme as in other countries: it did not break abruptly with the medieval tradition, religious literature did not disappear and it was during the Renaissance when ascetic and mystical authors arose in Spain.

Religious literature was led by writers such as Saint Teresa of Jesus, Saint John of the Cross, Fray Luis de Granada, Fray Luis de Molina, Saint Juan de Ávila and Fray Juan de los Ángeles. Miguel de Cervantes began to write his first works. The lyric poetry of this period is divided into two schools: the Salmantina (Fray Luis de León) and the Sevillana (Fernando de Herrera). Epic poetry culminates with Alonso de Ercilla, who dedicates La Araucana to Felipe II. In the theater, Lope de Rueda stands out, one of the first professional Spanish actors, considered a forerunner of the theater of Lope de Vega, who would be even more important in the reign of Felipe III, like Miguel de Cervantes.

Among the most famous painters were El Greco, Titian, Antonio Moro and Brueghel the Elder. Alonso Sánchez Coello was the chamber painter of Felipe II. It was the heyday of Spanish architects, among them Juan de Herrera, Juanelo Turriano, Francisco de Mora or Juan Bautista de Toledo, which resulted in the appearance of a new style that was characterized by the predominance of constructive elements, the absence decorative, straight lines and cubic volumes. This style was later baptized as Herreriano style. These famous architects built religious and mortuary buildings such as the Monastery of El Escorial or the Cathedral of Valladolid; civil or administrative such as the Casa de la Panadería in Madrid or the Casa de la Moneda in Segovia, and military such as the Citadel in Pamplona.

The most notable composers of sacred music during the reign of Philip II were Tomás Luis de Victoria and Francisco Guerrero. One of the last vihuela books was also published in 1576: El Parnaso by Esteban Daza. Alonso Lobo composed his well-known work Versa est in luctum on the death of Felipe II.

In fact, this era, in which great writers and playwrights excelled, and those who stood out under the government of Felipe III had just been born, is known as the Golden Age or the apogee of culture Spanish.

Science and technology

The "prudent king" acted as patron of numerous scientific projects, but most of them limited to mathematical, geographic, cosmographic and naval engineering subjects. In 1552 he created the Chair of Cosmography in the Seville House of Contracting, Pedro de Medina's book was explained. In 1581 he convened the first modern debate on naval construction and engineering between Diego Flores de Valdés, Cristóbal de Barros, Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa and Juan Martínez de Recalde, who exchanged views with the Santander Boards and Seville to define the traces, proportions, measurements and strengths of the new royal galleons. He even promoted the construction of several prototypes of steamships, ahead of his time, made by Jerónimo de Ayanz y Beaumont.

He founded the first Academy of Mathematics and Delineation in Europe in 1583 and gave it a building next to the Royal Palace, apparently in the Convent of Santa Catalina de Sena, naming the architect Juan de Herrera to direct it; he hired the prestigious Portuguese cosmographer Juan Bautista Labaña to occupy the chair. The humanist Pedro Ambrosio de Ondériz was commissioned to translate scientific texts from Latin into Spanish. Later, they were professors at the Juan Arias de Loyola Academy and the Milanese Giuliano Ferrofino.He also made an Alchemy Cabinet and created and endowed the Library of the Monastery of El Escorial, whose organization he entrusted to the humanist Benito Arias Montano. He ordered them by language and in 74 subjects, 21 of which were scientific. Pompeo Leoni brought Leonardo da Vinci's engineering codices from Milan at the king's express request long before the famous painter's scientific value was recognized. In 1562 a chair of Mathematics was created in Salamanca where the Copernican system was explained, entrusting its teaching to Andrés García de Céspedes. Its royal cosmographer Rodrigo Zamorano wrote Cronología y Repertorio de la razón de los tiempos —1585 and 1594—, translated The first six books of Euclid —1576— and produced a Carta de marear —1579— and a Compendium of the art of navigation. The monarch ordered a pioneering topographical description of Spain to be made and a geodesic map drawn up by the master Pedro Esquivel. He promoted and financed the geographical works of Abraham Ortelio and commissioned Ambrosio de Morales to explore the ecclesiastical archives and the botanist Francisco Hernández to study the Mexican fauna and flora.

During his reign, the "Calendar Commission" was created at the University of Salamanca in 1578, from which the Gregorian calendar would emerge in 1580, to which his kingdoms would be added the first and which is currently the calendar by which all nations and international organizations are officially governed.

Regarding the ethnography and Natural History of that period, it is worth highlighting the monumental Historia natural y moral de las Indias (1589), by José de Acosta (1540-1600), which addresses cosmographic, biological, botanical, geographical as well as religious, political and historical matters.

Surgery and urology were also studied at this time, such as the work of Francisco Díaz de Alcalá on kidney disease, this being one of the pioneering works in this field and, therefore, considered as the father of universal urology.

In the time of Felipe II, many activities were undertaken to analyze the waters of the empire, and protomedics such as Miguel Martínez de Leiva carried out studies and compendiums on the plague and its remedies.

Domestic policy

During his reign he faced many internal problems, among which are worth noting: his son Carlos, his secretary Antonio Pérez and the war in the Alpujarras. He also ended the Protestant pockets in Spain, located mainly in Valladolid and Seville.

Prince Charles (1545 to 1568) and the dynastic problem

Prince Carlos was born in 1545, the son of Philip's first wife, Maria of Portugal, whom he had married two years earlier and who died in childbirth. Characterized by his mental imbalance, of very possible genetic origin, since he had four great-grandparents (instead of the natural eight) and six great-great-grandparents (instead of sixteen), Carlos had a weak and sickly complexion. He was educated at the University of Alcalá together with the King's half brother, Don Juan of Austria. He conspired with little concealment with the Flemish rebels against his father. After astonishing scandals related to this, such as the attempt to stab the Duke of Alba in public, he was arrested by his own father, prosecuted and locked in his chambers. Later he was transferred to the Castillo de Arévalo where he died of starvation (he refused to eat) and in total delirium in 1568. This terrible event deeply marked, and for life, the monarch's personality.

From his second marriage, to Mary I of England, there were no children, but from his third marriage to Elizabeth of Valois he had two daughters, so that, when Elizabeth of Valois died in 1568, Philip II found himself with forty-one years old, widower and without male descendants. This was one of the worst years for Felipe II: the personal tragedy was joined by the rebellion in the Netherlands and the Alpujarras, the unstoppable advance of the Protestant and Calvinist heresy in France and Central Europe, Barbary piracy and the resurgence of the Ottoman threat after the failure of the siege of Malta and the death of Suleiman the Magnificent.

In 1570, Felipe II married for the fourth time with Ana of Austria, daughter of his cousin Emperor Maximilian II, with whom he had four children, of whom only one, Felipe (April 14, 1578-March 31). 1621), the future Felipe III, reached adulthood. The issue of descendants being finally resolved, Anne of Austria died in 1580. Felipe II did not remarry.

The rebellion in the Alpujarras (1568 to 1571)

In 1567 Pedro de Deza, president of the Royal Chancery of Granada, proclaimed the Pragmatics under the order of Philip II. The edict limited the religious, linguistic and cultural freedoms of the Moorish population. This provoked a rebellion of the Moors of the Alpujarras that Juan de Austria reduced militarily.

The crisis of Aragon (1590 to 1591) and Antonio Pérez

Antonio Pérez, from Aragon, was the king's secretary until 1579. He was arrested for the murder of Juan de Escobedo, a trusted man of Don Juan of Austria, and for abusing the royal trust by conspiring against the king. The relationship between Aragon and the crown had been somewhat deteriorated since 1588 due to the lawsuit by the foreign viceroy and the problems in the strategic county of Ribagorza. When Antonio Pérez escaped to Zaragoza and took refuge in the protection of the Aragonese fueros, Felipe II tried to prosecute Antonio Pérez through the Inquisition court to avoid Aragonese justice (the Aragon justice was theoretically independent of royal power). This fact provoked a revolt in Zaragoza that Felipe II reduced using force, beheading Juan de Lanuza y Urrea and eliminating the privileges and privileges of Aragon in order to be able to execute him.

Administrative reforms

The King's father, Carlos I, had ruled like an emperor, and as such, Spain and mainly Castile had been a source of military and economic resources for distant wars, of a strategic nature, difficult to justify locally since they responded to his personal ambition (and even more, to the ambitions of the House of Austria) and that they had become very expensive with the technological innovations of war. Everything was maintained with the Castilian funds and with the American wealth, which came directly from America to the Dutch, German and Genoese bankers without going through Spain.

Felipe II, like his predecessor, was an authoritarian king, and continued with the institutions inherited from Carlos I and with the same structure of his empire and autonomy of its components, but he ruled as a national king. Spain, and especially Castile, were the center of the empire, with its administration located in Madrid. Felipe II hardly visited their territories outside the peninsula and administered them through officials and viceroys, perhaps because he feared falling into the error of his father, Carlos I, who was absent from Spain during the years of the communal rebellions; perhaps because, unlike his father, who learned Spanish when he was very young, Felipe II felt deeply Spanish.

He turned Spain into the first modern kingdom, he carried out hydraulic reforms (the Monnegre dam) and a reform of the road network, with inns, with an administration (and a bureaucracy) unknown until then. Felipe II's administrators used to have university studies, mainly from the universities of Alcalá and Salamanca, the nobility also held administrative positions, although in fewer numbers. Notable examples of his meticulous administration are:

- In 1559, Felipe II decided to move the seat of the court and turned Madrid into the first permanent capital of the Spanish monarchy. Previously, probably from before his birth in Valladolid in 1527, under the reign of his father Carlos I, the Court was in Valladolid, thus until 1559. Since then, except for a short period of time between 1601 and 1606, under the rule of Felipe III, in which the capital temporarily returned to Valladolid, Madrid has been the capital of Spain and headquarters of the Government of the Nation.

- The Great and Congratful Navy, badly called "Invincible Burn", from which it was known to the name of the small group, while the English did not have any news of even all the ships that participated.

- The thirds were the best military units of their time. Created by his predecessor, Carlos I of Spain, they were decisive for Felipe II in the victories he won in front of the French, English and Dutch in his reign (see corresponding sections). They were experts in tactics such as siege (in Antwerp from 1584 to 1585).

- Apart from having the best soldiers he also had the best generals of his time, both on land and on the sea. Among these were Fernando Álvarez de Toledo and Pimentel—III duke de Alba de Tormes—, Alejandro Farnesio, Duke of Parma, Alvaro de Bazán and Juan de Austria, among others.

- Military innovations in every way. Apparition of the archbuceres and musketeers, who fought along with the piqueros and the Cavalry. Artillery was also available: from bronze cannons or cast iron, medium cannons, celebrity to falconetes. In the tactical aspect, it highlights the use of night surprise attacks (Encamisada). If it was a siege, the Tercios carried out works of entrenchment to surround the square and approach the cannons and mines to the walls. One of the squadrons remained in reserve to reject any attempted counterattack of the besieged.

- In the sea, the massive use of gallons was highlighted, as its combination of size, sail and the possibility of transporting armaments and troops made it suitable for the long ocean crossings, thus combining the capacity of transport of cargo ships with the power of fire that required the new techniques of war in the sea, allowing to have heavily armed transport boats.

- Carlos I created on February 27, 1537 the Marine Corps of Spain, making it the oldest in the world by permanently assigning to the galley squads of the Mediterranean the old companies of the sea of Naples. However, it was Philip II who created the current concept of disembarkation force, a concept that still lasts in our days.

- He spent a lot of money to create the best spy network of the time. The use of invisible ink and microscopic writing by Philip II's secret services is well known. Bernardino de Mendoza was a military, ambassador and head of secret services in various regions of the Spanish Empire under Philip II and during this time he was destined as a Spanish ambassador in Paris. One of the most important actions attributed to this ancestor of the current secret services was the murder of William of Orange at the hands of Balthasar Gérard.

- Creation of the Spanish Way, a land route to transport money and troops from the Spanish possessions in Italy, to the Spanish Netherlands.

- Trade with the Indias was heavily controlled. By law, these Spanish possessions could only trade with a port in Spain (first Seville, then Cadiz). The English, Dutch and French tried to break the monopoly, but it lasted for more than two centuries. Thanks to the monopoly, Spain became the richest country in Europe. This wealth allowed for wars against Protestants in Central and North Europe. It also caused enormous inflation in the XVIwhich practically destroyed the Spanish economy.

- Philip II was communicating almost daily with his ambassadors, viceroys and officers spread over the empire through a system of messengers that took less than three days to get to any part of the peninsula or about eight days to get to the Netherlands.

- In 1566 he carried out a monetary reform in order to increase the value of the gold shield and put in circulation different species of rich fleece.

- In 1567 Felipe II commissioned Jerónimo Zurita and Castro to gather the documents of State of Aragon and Italy and to bring them together with those of Castile in the castle of Simancas, creating one of the largest national archives of his time.

Territories attached to the Council of CastileTerritories attached to the Aragon CouncilTerritories attached to the Council of PortugalTerritories attached to the Council of ItalyTerritories attached to the Indian CouncilTerritories attached to the Council of Flanders covering the territories disputed with the United Provinces.

The government through Councils established by his father, continued to be the backbone of his way of running the state. The most important was the Council of State of which the king was the president. The King communicated with his Councils primarily through the Consultation, a document containing the Council's opinion on a subject requested by the King. There were also six regional Councils: that of Castilla, Aragon, Portugal, the Indies, Italy and the Netherlands and they exercised legislative, judicial and executive tasks.

Philip II also liked to have the opinion of a select group of advisers, made up of the Catalan Luis de Requesens, the Castilian Grand Duke of Alba, the Basque Juan de Idiáquez, the Burgundian Cardinal Antonio Perrenot de Granvela and the Portuguese Ruy Gómez de Silva and Cristóbal de Moura distributed by different offices or being members of the Council of State. Felipe II and his secretary were directly in charge of the most important matters, another group of secretaries was dedicated to daily affairs. With Felipe II the figure of the king's secretary reached great importance, among his secretaries are Gonzalo Pérez, his son Antonio Pérez, Cardinal Granvela and Mateo Vázquez de Leca. In 1586 he created the Junta Grande, made up of officers and controlled by secretaries. Other boards dependent on it were the Militia, Population, Cortes, Excise and Presidents.

Finances

During his reign, the Royal Treasury declared bankruptcy three times (1557, 1575 and 1596), although, in reality, they were suspensions of payments, technically very well elaborated according to modern economics, but completely unknown at the time.

Philip II inherited a debt of about twenty million ducats from his father and left his successor one that was five times that debt. In 1557, shortly after the king came to power, the Crown had to suspend the payments of its debts, declaring the first bankruptcy. But the revenues of the Crown doubled shortly after Felipe II came to power, and at the end of his reign they were four times higher than when he began to reign, since the tax burden on Castile quadrupled and the wealth from America reached historical values.. As with its predecessor, the wealth of the Empire rested mainly with Castile and depended on advances at high interest from Dutch and Genoese bankers. On the other hand, income from America was also important, which accounted for between 10% and 20% per year of the wealth of the Crown. The biggest consumers of income were the troubles in the Netherlands and the politics in the Mediterranean, together some six million ducats a year.

The state of finances depended entirely on the Castilian economic situation. The Netherlands were the main recipients of Castilian wool and, due to the already open conflict in the Netherlands, the wool route was interrupted, which produced a recession in the Castilian economy in 1575. As a consequence, in that same year there was a second suspension of payments upon the declaration of the second bankruptcy. In 1577 an agreement was reached with Genoese bankers to continue advancing money to the Crown, but at a very high price for Castile, which worsened its recession. This is known as "the General Remedy" of 1577, which consisted of a long-term debt consolidation, which could reach seventy or eighty years. Thus, juros (bonds) were delivered to the creditors as a commitment from the Crown to return the money with an interest of 7%. Said money would be returned as liquidity returned and with the guarantee of American metals. At the same time, between 1576 and 1588, Felipe used the financial intermediation of Simón Ruiz, who facilitated payments, collections and loans through bills of exchange.

Before Felipe II, there were already various taxes: the alcabala, a customs tax; the ecclesiastical tax crusade; the subsidy, tax on income and land and the real thirds, taxes on military orders. Felipe II, in addition to raising these during his reign, introduced others, including the toilet in 1567, taxes on parishes. Felipe II managed to collect up to 20% of the wealth of the Crown from the Church, which led to criticism from some ecclesiastics.

In 1590 the Cortes approved the millions, consisting of eight million ducats a year for the following six years, which were dedicated to the construction of a new Navy and to bloody military policy. This ended up ruining the Castilian cities and destroying the already weak attempts at industrialization that remained. In 1597 there was a new suspension of payments when the third bankruptcy was declared, resorting to a new "General Remedy". This caused a gigantic and disproportionate indebtedness of the Crown, but allowed the continuation of foreign policy.

After the already bad economic situation in Castile that he received from Carlos I, Felipe II left Spain on the brink of crisis. The life of the Spaniards of the time was hard; the population endured brutal inflation, for example, the price of grain rose 50% in the last four years of the century; the tax burden, both on producers and consumers, was excessive. Due to inflation and the tax burden, there were fewer and fewer businesses, merchants and businessmen left their businesses as soon as they could acquire a title of nobility, with its low tax burden. In the last Cortes, the deputies protested effusively against another demand for more money from the king, urging a withdrawal of the armies from Flanders, seek peace with France and England and concentrate their formidable military and maritime power in the defense of Spain. and his empire. In 1598, Felipe II signed peace with France; with Flanders he did not reach an agreement and England did not make things easy with her constant piracy and hostility towards Spain. The situation would worsen with Felipe III due to the reduction in income from America and even more voices would begin to be heard about Castile not being able to continue bearing the burden of so many wars and that the rest of the members should also contribute to the common good..

The fiscal pressure in Aragon, without being as brutal as that of Castile, was not much lower. But in this case, most of the proceeds were not going to form part of the Spanish Crown but, thanks to the protection of the fueros, they became part of the wealth of the oligarchy and the nobility of those kingdoms. Trade in the Mediterranean for Aragon, especially Catalonia, was still badly damaged by Turkish rule and competition from the Genoese and Venetians.

Income from other parts of the empire—the Netherlands, Naples, Milan, Sicily—was spent on their own needs. The annexation of Portugal was financially a great effort for Castile, since it began to pay for the maritime defense of its extensive empire without Portugal contributing anything to the whole.

Most historians agree in emphasizing that the situation of poverty that plunged the country at the end of his reign is directly related to the burden of the Empire and its role as defender of Christianity. During the reign of Felipe II there was hardly a respite in the military effort. He had to combine two during most of his reign: the Mediterranean against Turkish power and the Netherlands against the rebels. At the end of his reign he had three simultaneous fronts: the Netherlands, England and France. The only power capable of supporting this burden in the XVI was Spain, but with questionable benefits and at a very high price for its population.

Foreign Policy

Characterized by its wars against: France, the Netherlands, the Turkish Empire and England.

Wars with France

Philip II maintained the wars with France, due to the French support for the Flemish rebels, obtaining a great victory in the battle of San Quentin, fought on August 10, 1557, the feast of San Lorenzo, in memory of which he made build the monastery of El Escorial, a building with a grid-shaped plan that symbolizes the martyrdom of the saint (1563-1584). In this monumental and sober palace, the largest of its time —already then called the eighth wonder of the world—, specifically in the Royal Crypt, almost all the Spanish kings and their closest family members have been buried ever since. This victory against the French was compounded by a later decisive victory at the Battle of the Gravelines in 1558.

As a consequence of these sudden Spanish successes, the Peace of Cateau-Cambrésis of 1559 was signed, a treaty in which France recognized Spanish supremacy, Spanish interests in Italy were favored and the marriage with Isabel de Valois, queen, was agreed from Spain. But, in Flanders, the problems continued from 1568 due to the support of the Flemish rebels by the French Huguenots.

At the end of the Italian wars in 1559, the House of Austria had managed to establish itself as the leading world power, to the detriment of France. The states of Italy, which during the Middle Ages and the Renaissance had accumulated power disproportionate to their small size, saw their political and military weight reduced to that of secondary powers, some of them disappearing.

In 1582, Álvaro de Bazán defeated a squadron of French corsairs in the battle of Terceira Island, in which for the first time in history land infantry forces were used to occupy the beach, ships and land, what is considered as "the birth of the marine infantry." In 1590, taking advantage of the death of the Cardinal de Bourbon, King of France for the Catholic League, Philip II intervened in France's religious wars against Henry IV. In the Estates General of 1593 convened by the Duke of Mayene, as a rival lieutenant general to Henry IV, they refused to recognize Isabel Clara Eugenia, daughter of Philip II, as Queen of France, which Henry IV took advantage of to convert to Catholicism. Felipe II's position and hopes faded until the Peace of Vervins (1598), in which the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis was restored.

Conflicts with the Netherlands

Philip II had received as an inheritance from his father, Carlos I, the Netherlands together with Franche-Comté, so that Spain, at that time the most powerful nation in the world, would defend the Empire against France. For this reason, it was both a strategic point and a point of weakness for Felipe II. Strategic, since in the middle of the XVI Antwerp was the most important port in Northern Europe, serving as the base of operations for the Spanish Navy, and a center where goods from all over Europe were traded and Castilian wool was sold. Wool, from Merino sheep, processed in the Netherlands that, sold at reasonable prices, would arrive manufactured in Spain, with the corresponding added value, but less than if it had been manufactured in the Peninsula, since labor was cheaper there. Spain was a focus of inflation for the Netherlands due to the gold coming from America, favoring high salaries.

A weakness, because for the Netherlands it not only meant a change of king, but also a change of "owner", they went from being part of an empire to being part of the most powerful kingdom of the time. Unlike Castile, Aragon and Naples, the Netherlands were not part of the heritage of the Catholic Monarchs, and they saw Spain as a foreign country. This is how the citizens of the Netherlands felt it themselves, since they saw, unlike Carlos I, a foreign king (born in Valladolid, with the Court in Madrid, never lived in those territories and delegated the government to him). To this we must add the religious clash that was brewing within Flanders, and that would be fueled by the position of Felipe II on the religious level, the religious wars returned to the heart of Europe after the Schmalcald war.

Governed by their sister Margaret of Parma since 1559, they confronted the rebellious nobles who demanded greater autonomy and the Protestants who demanded respect for their religion, starting the Eighty Years' War. However, Felipe II was of another opinion. The king wanted to apply the Tridentine agreements, as he had demanded of Catherine de' Medici in France against the French Huguenot nobility. Upon learning in the Netherlands of the decision to apply the Tridentine agreements, the same civil authorities were reluctant to apply the sentences handed down by the inquisitors and, as a result of great discomfort, an atmosphere of revolution began. The lower nobility gathered in Brussels on April 5, 1566 in the governor's palace, being despised as "beggars", an adjective that the following nobles would take in their claims, dressing as such. The members of the Breda compromise sent Floris de Montmorency, Baron de Montigny, to Madrid, and then the Marquis de Berghes, who would never return.

After increasing tension and conflicts in Antwerp, the governor asked William of Orange to bring order, he reluctantly accepted but pacified the city. The Prince of Orange, the Count of Egmont and the Count of Horn again asked Marguerite of Parma for more freedom. She let her brother know, but Felipe II did not change his mind and warned the pope of her intentions:

[...] you can assure His Holiness that before suffering the least thing to prejudice the religion or the service of God, I would lose all my states and a hundred lives that I had, for I do not think, nor want to be lord of heretics [... ]

Before this news arrived, on August 14 a group of uncontrolled Calvinists stormed the main church of Saint-Omer. A widespread rebellion followed in Ypres, Courtrai, Valenciennes, Tournai, and Antwerp. Felipe II received Montigny and promised to convene the Council of State of Spain. On October 29, 1566, the king summoned his closest advisers: Éboli, Alba, Feria, Cardinal Espinosa, Don Juan Manrique and the Count of Chinchón, together with the State Secretaries Antonio Pérez and Gabriel Zayas. The agreement was to proceed urgently, and, despite the differences in form, the monarch opted for force. Thus it was agreed to send the III Duke of Alba to quell the rebellions. This fact led to a confrontation between Prince Don Carlos and the Duke of Alba, since the heir was displaced from his affairs. On August 28, the Duke of Alba arrived in Brussels. The Duke of Alba - at the head of the army - quickly carried out a harsh repression, executing the rebellious nobles, which led to the resignation of Margaret of Parma as governor of the Netherlands, a resignation immediately accepted by her brother the king. Furthermore, on September 9, Egmont and Horn were seized, and their throats beheaded on June 5, 1568.

Philip II sought solutions with the appointments of Luis de Requesens, Juan de Austria (died in 1578) and Alejandro Farnesio, who achieved the subjugation of the southern Catholic provinces in the Union of Arras. Given this, the Protestants formed the Union of Utrecht. On July 26, 1581, the provinces of Brabant, Gelderland, Zutphen, Holland, Zeeland, Frisia, Mechelen and Utrecht annulled in the States General, their link with the King of Spain, by the act of abjuration, and elected as sovereign to Francis of Anjou. But Felipe II did not renounce those territories, and the governor of the Netherlands Alejandro Farnesio began the counteroffensive and recovered a large part of the territory to the obedience of the King of Spain, especially after the siege of Antwerp, but part of them returned to lose after Mauricio de Nassau's campaign. Before the death of the King of Spain, the territory of the Netherlands, in theory the seventeen provinces, passed jointly to his daughter Isabel Clara Eugenia and his son-in-law Archduke Alberto of Austria by the Assignment Act of May 6, 1598.

Trouble with England

Philip II fought against the English Crown for religious reasons, for the support they offered to the Flemish rebels and for the problems caused by the English corsairs who stole American merchandise from Spanish galleons in the Caribbean area from 1560 Thus, the main scenarios for the fighting would be the Atlantic and the Caribbean.

The burden caused by the continuous English and French piracy against their ships in the Atlantic and the consequent decrease in the gold income from the Indies has been shown in various literary works and especially in films. However, more in-depth investigations indicate that this piracy actually consisted of several dozen ships and several hundred pirates, the first being of low tonnage, so they could not face the Spanish galleons, having to settle for small ships or the that they could get away from the fleet.

Secondly, there is the fact that, during the XVI, no pirate or privateer managed to sink any galleon; In addition to some 600 fleets chartered by Spain (two per year for about three centuries), only two fell into enemy hands and both by navies, not by pirates or corsairs.

The execution of the Catholic queen of Scotland, Mary Stuart, led him to send the so-called Great and Happy Armada (in the black legend, Invincible Armada) in 1588, which failed. The failure made possible greater freedom for English and Dutch trade, a greater number of attacks on Spanish ports —such as that of Cádiz that was burned by an English fleet in 1596— and, likewise, the English colonization of North America. From these events and until the end of the war, Spain and England achieved equal victories in the naval battles waged by both kingdoms, both at sea and on land. With what the war remained in a tie of losses of resources for the countries until the end. While the English plundered Spanish possessions and never achieved the objective of capturing a fleet from the Indies, the Spanish Armada prepared without much success to invade England, repelled some English attacks and Spanish corsairs captured tons of goods from English ships. The English attacks (and those of pirates or corsairs in their pay) used to end in failure with not inconsiderable losses, among which the failure of the Invincible English (or Counterarmada) stood out. The situation was balanced, until Felipe III signed the Treaty of London in 1604, with James I, successor to Elizabeth I. In some of the expeditions under his command, he landed in the south of England or in Ireland (battle of Cornwall: Carlos de Amésquita landed in 1595 in the south of England).

Philip II urgently reinforces his squadron, orders twelve new gallons and by 1591, the reconstituted backbone of his navy already has nineteen of these vessels, among which we find three new, two captured the English, and four veteran survivors of Portugal [...] Alonso de Bazán, brother of the late Alvaro de Bazán, proceeds against Thomas Howard with a fleet of 55 candles, achieving catching the English between Punta Delgada and Punta Negra [...] The English flee, but the gallon Revenge [...] is approached and imprisoned. [...] In 1595 (the English) prepare the final take and installation of a base in Panama [...] with a fleet of 28 ships. But things were not good for pirates [...] Drake's command, they march to Panama, and that's where their existence ends. Sir Francis [...] After various vicissitudes, only eight ships of the expedition managed to return to the homeland. After the English counteroffensive Carlos de Amezquita disembarks on the coasts of Cornwall [...] It sows the Pistan in Pezance and other nearby locations and withdraws. [...]Victor San Juan. The naval battle of the Dunes. 2007. (p. 66 and 67)

In addition, a sophisticated system of escort and intelligence thwarted most privateering attacks on the Fleet of the Indies beginning in the 1590s: the buccaneering expeditions of Francis Drake, Martin Frobisher, and John Hawkins at the start of that decade were defeated.

Wars with the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, which had already been an opponent of Carlos I of Spain, turned to confront the Spanish Empire. In 1560, the Turkish fleet - which was a power of the first order - had defeated the Christians in the battle of Los Gelves. The siege of Malta, in 1565, however, was unsuccessful and also considered one of the most important sieges in military history and, from the point of view of the defenders, the most successful.

In 1570, after a few years of tranquility, the Turks began an expansion attacking several Venetian ports in the eastern Mediterranean and conquered Cyprus from Venice with 300 ships and laid siege to Nicosia. Venice asked the Christian powers for help, but only Pope Pius V responded. He managed to convince the king of Spain to help too, and an army was formed to face the Turks. This armada met in the port of Suda, on the island of Candia, in Crete. This coalition, known as the Holy League, faced the Turkish fleet in the Gulf of Lepanto, on October 7, 1571, igniting the Battle of Lepanto ("the highest occasion that the centuries have seen"), which ended in a great victory of the Catholic allies. This is how the Marquis de Lozoya describes it:

For two hours he fought with ardor on both sides, and for two times the Spaniards of the bridge of the Turkish royal galley were rejected; but in a third onslaught they annihilated the Jenizars who defended it and, wounded the Admiral of an ark, a Christian remero cut off his head. When a Christian pavilion was set up in the Turkish galley, the Christian ships seized the attack against the Turkish captains who did not surrender; but at last the Turkish central fleet was destroyed.

After this combat, the Turks rebuilt their fleet so that, again allied with the Barbary pirates, it was still the most powerful in the Mediterranean. For almost two years the Ottoman fleet avoided combat and it was not until after the taking of Tunis and La Goleta by don Juan de Austria, in 1573, when Selim II, successor of Suleiman the Magnificent, sent a force of 250 warships and a contingent of about 100,000 men to reconquer both places, work in the that nearly 30,000 men perished, albeit with satisfactory results. It was the last great battle in the Mediterranean.

However, what the battles and combats had not resolved, was resolved by diplomacy and international negotiations, for the benefit of both empires. Felipe II saw how the war in Flanders was getting worse, and Selim II had to face the war with Persia. Both were waging military campaigns on other borders, and neither felt strong enough to continue the conflict. Convinced of the different situation that both empires were experiencing, they decided to sign a series of truces that ended up definitively averting the war in the Mediterranean for a few years.

Atlantic and Pacific expansion

Philip II continued with the expansion in American lands and even the Philippine islands, conquered by Miguel López de Legazpi (1565-1569), were added to the Crown, although it was Ruy López de Villalobos who named them that in his honor. The Spanish colonization of the islands also coveted by the English, Dutch and Portuguese was not assured until 1565 when Miguel López de Legazpi, sent by the viceroy of New Spain, built the first Spanish settlement in Cebu. The city of Manila, capital of the archipelago, was founded by Legazpi himself in 1571. Once the circuit of ocean currents and favorable winds for navigation between America and the Philippines was discovered, the regular fleet route between Manila and Acapulco, Mexico was established., known as the Manila Galleon. Florida was settled in 1565 by Pedro Menéndez de Avilés by founding San Agustín and quickly defeating an illegal attempt by French captain Jean Ribault and 150 men to establish a supply post in Spanish territory. San Agustín quickly became a strategic defense base for Spanish ships full of gold and silver returning from the Indies.

In the South Pacific, off the coast of present-day Chile, Juan Fernández discovered a series of islands between 1563 and 1574. He gave the archipelago his own name, eventually becoming known as the Juan Fernández archipelago. The first Europeans to reach the islands that are now New Zealand did so on the probable trip of Juan Jufré and the sailor Juan Fernández to Oceania, the occasion in which they would have discovered New Zealand for Spain, at the end of 1576; this event was based on a document presented to Philip II and on archaeological remains (Spanish-style helmets) found in caves at the upper end of the north island.

The conquest of China for the Spanish Empire was even considered during his reign. As evidenced by a letter from the governor and archbishop of the Philippines, in which both told him that if he sent them 5,000 men and 30 ships they could do with China what Hernán Cortés had done in Mexico. However, Felipe II never responded to that letter.

The domains in Africa were expanded. Mazagán, incorporated into the Empire because it was a Portuguese colony, like Casablanca, Tangier, Ceuta and the island of Perejil. The rock of Vélez de la Gomera was reconquered from the Arabs, in an operation led by García Álvarez de Toledo y Osorio, Marquis of Villafranca del Bierzo and Viceroy of Catalonia. In addition, due to the annexation of Portugal, the colonies that this territory possessed in Asia were also added: Macao, Nagasaki and Malacca.

Family

Married couples and children

- He fell in the first nuptists with his first sister, the Infanta María Manuela of Portugal (1527-1545) on 15 November 1543. They had a single son:

- Charles of Austria (1545-1568), Prince of Asturias.

- He fell into second marriages with his fathers' cousin Charles and Elizabeth, Queen Mary I of England (1516-1558), in Winchester on 25 July 1554. They had no children.

- His third marriage to Isabel de Valois (1546-1568) took place on 22 June 1559. They had five daughters:

- Two twin girls (August 1564), miscarriage.

- Isabel Clara Eugenia (1566-1633), married to her cousin, Archduke Alberto of Austria.

- Catalina Micaela (1567-1597), married to Carlos Manuel I, Duke of Saboya.

- Joan of Austria (3 October 1568), died within a few hours of birth.

- The Archduke Ana of Austria (1549-1580) fell in fourth nuptials with her niece on 14 November 1570. Ana was the daughter of Maximilian II of Habsburg (the first of Philip) and of Mary of Austria and Portugal (the sister of Philip). The couple had four sons and one daughter:

- Fernando (4 December 1571-18 October 1578), Prince of Asturias.

- Carlos Lorenzo (12 August 1573-30 June 1575).

- Diego Félix (15 August 1575-21 November 1582), Prince of Asturias.

- Philip (14 April 1578-31 March 1621), prince of Asturias, future king of Spain as Philip III.

- Mary (14 February 1580-5 August 1583).

Lovers

- Isabel Osorio (1522-1589) lady of company of Philip II's sister. He had two sons, Bernardino and Pedro, of whom he never gave the father's name.

- Euphrasian de Guzmán (c. 1540-c. 1599) was possibly a lover of Philip II between 1559 and 1564, while he expected his wife Isabel de Valois to fulfill the age of marriage. He had a son and a daughter, being one of them attributable to Philip II without having ever confirmed such a point.

Semblance

In 1554, according to Scottish observer John Elder, Philip II was of average height, on the small side, and continues:

... face is very similar, with wide front and gray eyes, with a straight nose and a varonil shear. From the forehead to the tip of the chin his face is steep; his way of walking is worthy of a prince, and his porte so right and straight that he does not lose an inch of height; with the yellow head and beard. and so, to conclude, it is so well provided of body, arm, and leg, and the same is all other members, that nature cannot work a more perfect model.

Since the annus horribilis of 1568, the Renaissance monarch accentuated his severity, and over time he became assimilated to the stereotype of the black legend, as serious in gesture as in word. He was taciturn, prudent, calm, constant and considerate, and very religious, although without falling into the fanaticism of which his enemies accused him. In 1577 he described it thus:

... of mediocre stature, but very well provided; its blond hairs begin to bleached; its face is beautiful and pleasant; its humor is melancholic (...) He deals with matters without rest and in it he takes extreme work because he wants to know everything and see everything. He gets up early and works or writes until noon. Eat then, always at the same time and almost always of the same quality and the same amount of dishes. Drink in a glass glass glass of mediocre size and empty it twice and a half. (...) It sometimes suffers from stomach weakness, but little or no drop. Half an hour after the meal unpacks all the documents in which you must put your signature. Done this, three or four times a week goes in chariot to the field to hunt with crossbow the deer or the rabbit.

His psychological character was reserved and he hid his shyness and insecurity under a seriousness that earned him an image of coldness and insensitivity. He didn't have many friends, and none of them fully trusted him, but he wasn't the dark and embittered character that has been handed down through history through black legend.

He was considered an intelligent man, highly educated and educated, fond of books, architecture and collecting works of art: paintings, watches, weapons, curiosities, rarities. Very rigorous in defending Catholicism, he discarded El Greco in El Escorial, considering that his style did not conform to religious orthodoxy, but he treasured numerous extravagant works by Hieronymus Bosch and mythologies by Titian. obviously erotic. Felipe II was also a great fan of hunting and fishing.

Death

Felipe II had, during most of his life, a delicate health. He suffered numerous illnesses and during the last ten years of his life he was bedridden by gout. He came to lose the mobility of his right hand, unable to sign the documents. At the end of the spring of 1598 he had himself transferred by litter from Madrid to El Escorial. He received Communion for the last time on September 8, since the doctors forbade it from that moment, for fear of drowning when swallowing the host. He settled in a small room from whose bed and through a small opening he could see the main altar of the basilica and the tabernacle that rested on it. Despite his immense suffering, he had meticulously arranged the smallest details of his funeral. He sent for his favorite daughter and his son, to whom he was ashamed in their droppings and murmured to them "I wanted, my children, that you were present so that you could see what the kingdoms and dominions of this world come to end." At five o'clock in the morning on Sunday, September 13, 1598, with a crucifix in one hand and a lighted candle in the other and his eyes fixed on the tabernacle, he died in the monastery of El Escorial, where he was buried at the age of seventy-nine. one years. His agony had lasted fifty-three days, during which he suffered various illnesses: gout, osteoarthritis, tertian fever, abscesses, and dropsy, among others.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Felipe II of Spain | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Succession

Cinema

| Year | Movie | Director | Actor |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | In the King's Palace (In the Palace of the King) | Emmett J. Flynn | Sam De Grasse |

| 1934 | Willem van Oranje | Jan Teunissen | Cruys Voorbergh |

| 1937 | Fire Over England | William K. Howard. | Raymond Massey |

| 1940 | The Sea Hawk | Michael Curtiz | Montagu Love |

| 1946 | Monsieur Beaucaire | George Marshall | Howard Freeman |

| 1954 | The mayor of Zalamea | José Gutiérrez Maesso | Fernando Rey |

| 1955 | The Princess of Eboli | Terence Young | Paul Scofield |

| 1962 | Il dominatore dei sette mari | Rudolph Maté and Primo Zeglio | Umberto Raho |

| 1966 | El Greco | Luciano Salce | Fernando Rey |

| 1991 | Don Juan in Hell | Gonzalo Suárez | Iñaki Aierra |

| 1998 | Elizabeth | Shekhar Kapur | George Yiasoumi |

| 2005 | Filmmakers against magnates | Carlos Benpar | Antonio Regueiro |

| 2007 | Elizabeth: the golden age | Shekhar Kapur | Jordi Mollà |

| 2008 | The conjure of El Escorial | Antonio del Real | Juanjo Puigcorbé |

| 2010 | The Princess of Eboli | Bethlehem Macías | Eduard Fernández |

| 2016 | Ministry of Time (TV) | Carlos Hipólito (Temporada 2, Episode 13) and Jorge Clemente (Temporada 4, Episode 3) | |

| 2016 | Charles, emperor king (TV) | Oriol Ferrer, Salvador García Ruiz and Jorge Torregrossa | Pablo Arbués

Álvaro Cervantes Marcel Borràs |

| 2017 | Queens (TV) | José Luis Moreno and Manuel Carballo | Adrian Castiñeiras |

Contenido relacionado

511

491

145