Phascolarctos cinereus

The koala (Phascolarctos cinereus) is a species of diprotodont marsupial in the family Phascolarctidae, endemic to Australia.

It is the only extant representative of the family Phascolarctidae, and its closest living relatives are the wombats. It lives in the coastal areas of the eastern and southern Australian regions, in the states of Queensland, New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia. It is easily recognizable by its stocky body with no tail, large head with round fluffy ears, and large spoon-shaped nose. They measure between 60 and 85 cm and weigh from 4 to 15 kg. Their coat color ranges from silver gray to chocolate brown. The northern populations are usually smaller and lighter in color than the southern ones, so it is believed that they may be a separate subspecies, although this possibility is under discussion.

They live in open areas of eucalyptus forests, the leaves of which make up the bulk of their diet. Because this diet provides a low amount of nutrients and calories, koalas lead a sedentary life, often sleeping up to twenty hours a day. They are asocial animals and there is only a bond between the mothers and their dependent young. Adult males communicate with loud roars that intimidate rivals and attract females. Males signal their presence with secretions from scent glands located on their chest. As in other marsupials, their young are born without being fully developed and immediately climb into their mothers' pouches, where they remain for their first six or seven months of life; the young are fully weaned by the time they are one year old. They have few parasites and natural predators, though they are threatened by various pathogens, including chlamydial infections and koala retrovirus, as well as bushfires and droughts.

There is evidence that Aboriginal Australians already hunted these animals and they have been depicted in their myths and rock art for millennia. The first recorded encounter between a European and a koala occurred in 1798, and a picture of the animal was published by naturalist George Perry in 1810. Botanist Robert Brown wrote the first detailed scientific description of the koala in 1814, although his work remained unpublished for 180 years. years. Ornithologist and artist John Gould illustrated and described these animals, introducing the species to the general British public and throughout the 19th century other English scientists revealed more details about its biology.

Because of its distinctive appearance, it is recognized worldwide as one of the symbols of Australia. It is the state emblem for Queensland's wildlife. The species is listed as vulnerable on the International Union for Conservation of Nature Red List. The Australian government also lists specific populations in Queensland, New South Wales and the Capital Territory as vulnerable in their national environmental legislation. In the early 20th century it was hunted in large numbers by European settlers primarily for its fur. Its greatest current threat is the destruction of its habitat caused by agriculture and urbanization. As with most Australian wildlife, it is illegal to keep koalas as pets, both in Australia and elsewhere in the world.

Etymology

From its scientific name, the genus, Phascolarctos, derives from the Ancient Greek φάσκωλος pháskōlos, 'bag', and ἄρκτος árktos, 'bear,' while the specific name, cinereus, comes from Latin and means 'ash-coloured'.

Its common English name, koala, comes from gula, from the Dharug language, spoken by some native peoples of Australia; although the vowel 'u' it was written in the English spelling as 'oo' (coola or koolah) later became 'oa', possibly in error. Aboriginal tribes in Australia use names such as cullawine, koolawong, colah, karbor, colo, coolbun, < i>boorabee, burroor, bangaroo, pucawan, banjorah or burrenbong i> to refer to this animal, many of which with the meaning 'does not drink',

Because of its teddy bear-like appearance, it is sometimes referred to as a "koala bear", though it is not really related to the animal, as it is a marsupial, not an ursid.

Taxonomy and evolution

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Cylogenetic tree of Diprothodontia (including external groups) |

French zoologist Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville designated the koala the generic name Phascolarctos in 1816, though he decided not to assign it a specific name until a later revision. The German Georg August Goldfuss assigned it the binary name Lipurus cinereus in 1819, but since Phascolarctos had been published first, it has priority as the scientific name of the genus according to the Code International Zoological Nomenclature. French naturalist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest proposed Phascolartos fuscus in 1820, considering animals with brown fur to be a different species from gray ones. Other names proposed by European authors were Marodactylus cinereus by Goldfuss in 1820, P. flindersii by René Primevère Lesson in 1827 and P. koala by John Edward Gray in 1827.

The koala is classified with the wombats (family Vombatidae) and other extinct families (such as Palorchestes, Thylacoleonidae, and Diprotodontidae) in the suborder Vombatiformes of the order Diprotodontia. The vombatiforms are a sister group to a clade that includes macropodiforms (kangaroos and wallabies) and possums. The ancestors of the vombatiforms were probably arboreal, and the koala evolutionary lineage was possibly the first to branch about 40 million years ago, during the Eocene.

The modern koala is the only extant member of the Phascolarctidae, a family that came to include several genera and species. During the Oligocene and Miocene, koalas lived in forests and had less specialized diets. Some of these species, such as Nimiokoala greystanesi and some species of Perikoala, were about similar to the modern koala, while others, such as those of the genus Litokoala, were half to two-thirds the size of today. Like modern species, prehistoric koalas had well-structured ears. developed, suggesting a development of long-distance vocalizations and sedentarism at an early time. During the Miocene, the Australian mainland began to dry out, causing the decline of rainforests and the expansion of open eucalypt forests. The genus Phascolarctos diverged from Litokoala at the end of this period and underwent several adaptations that allowed it to live on a specialized diet of eucalyptus leaves, as a change of the palate toward the front of the skull, an increase in the size of the molars and premolars, a decrease in the size of the pterygoid canal, and a greater gap between the molars and incisors.

During the Pliocene and Pleistocene, Australia experienced changes in its climate and vegetation, and koala species grew in size. P. cinereus may have arisen as a dwarf form of the giant koala (P. stirtoni). The reduction in the size of large mammals is considered a common phenomenon throughout the world during the Late Pleistocene and several Australian mammals, such as Macropus agilis , are traditionally considered to be products of this phenomenon. However, a 2008 study questioned this hypothesis, stating that P. cinereus and P. stirtoni were sympatric from the Middle to Late Pleistocene or even the Pliocene. The fossil record of the modern koala extends at least to the Middle Pleistocene.

Genetics and variations

There are three distinct traditionally recognized subspecies: the Queensland koala (P. c. adustus, Thomas 1923), the koala New South Wales koala (P. c. cinereus, Goldfuss 1817) and Victoria koala (P. c.victor, Troughton 1935). They differ in the color and thickness of their fur, their body size, and the shape of their skulls. The Queenslander is the smallest of the three, with a shorter, silver-colored coat and a smaller skull; Victoria's is the largest, with a larger skull and longer brown fur. The limits of these variations are set within the borders of these states, and their status as a subspecies is still disputed. A 1999 genetic study suggests that these variations represent distinct populations with limited gene flow between them and that the three subspecies form a single evolutionarily significant unit. Other studies concluded that koala populations exhibited high levels of inbreeding and low variability. It was observed that in the northern regions there was a greater genetic diversity, while in the southern ones there was less diversity and a higher level of inbreeding, which was consistent with some abnormalities observed among others, in the testicles, in these southern populations. At the continental level there are clear biogeographical barriers such as the Brisbane Valley, the Hunter Valley and the Clarence River, which impede gene flow between populations. This low genetic diversity may have been a feature of koala populations since the Pleistocene. late. Rivers and roads have been shown to limit gene flow and contribute to the genetic differentiation of populations in south-east Queensland.

In 2013, scientists from the Australian Museum and Queensland University of Technology announced that they had sequenced the koala genome.

The koala genome is made up of 16 chromosomes. The centromeres are smaller in marsupials than in eutherians (for example, mice or humans). 47.5% of the koala genome is made up of repeating sequences, 44% of these are transposable elements. In terms of coding regions, 6124 protein-coding genes have been identified.

Anatomy and Physiology

It is a stocky animal, with a large head and vestigial or non-existent tail. Its body length is 60-85 cm with a weight of < span style="white-space:nowrap">4 to 15 kg, making it one of the largest arboreal marsupials. Victorian koalas weigh almost twice as much as Queensland koalas. species does not display marked sexual dimorphism, although males are 50% larger than females; males are also distinguished from females by their more curved nose and by the presence of pectoral glands (which produce odorous secretions), which are visible as hairless patches. Like most marsupials, the male has a bifurcated penis, and the female has two lateral vaginas and two separate uteri. The skin covering the male's penis contains natural bacteria that play an important role in fertilization. The opening of the female's pouch can be contracted by means of a sphincter to prevent the hatchlings from falling off.

Their fur is longer and denser on the back and shorter on the belly. The ears have bushy hair both inside and outside. The fur on the back varies from light gray to chocolate brown, while the fur on the belly and hindquarters is whitish. the back is the most effective insulator of all marsupials and is highly resistant to wind and rain, while the skin on the belly can reflect solar radiation. Its sharp, curved claws are well adapted for climbing trees. Its large front legs have five fingers, two of them (the first and the second) opposite the other three, which allows them to grasp small branches. On the hind feet, the second and third toes are conjoined (a typical feature among diprotodonts) and the claws of these fused toes (which are still separated) are used for grooming. Like humans and other primates, koalas they have dermal papillae on their legs. It has a stout skeleton and a short, muscular trunk with proportionally long forelimbs that contribute to its climbing and clinging abilities. Strong thigh muscles that attach to the tibia lower than in other animals give them extra strength when climbing. They have a cartilaginous pad at the end of their spine that helps them be more comfortable when they perch on the branches of trees.

Weighing just 19.2g, koalas have one of the smallest brains to body weight ratio of any mammal, 60% smaller than that of a typical diprotodont. The surface of the brain is fairly smooth, a common feature in more "primitive" animals (plesiomorphy). It occupies only 61% of the cranial cavity and is pressed against the inner surface by cerebrospinal fluid. The function of this relatively large amount of fluid is unknown, although one possibility is that it acts as a shock absorber, absorbing shock and protecting the brain if the animal falls from a tree. The small size of its brain may be an adaptation to the restrictions. energy requirements imposed by their diet, which is insufficient to support a larger brain. Due to their small brains, koalas' ability to carry out complex or unfamiliar behaviors is limited; for example, when offered leaves torn from a tree on a flat surface, the animal cannot adjust to the change in its normal feeding routine and does not eat them.

Their sense of smell is normal, and they are known to sniff the oils of individual branches to assess their edibility. Their nose is quite large, covered with leathery skin. Its rounded ears provide good hearing and it has a well-developed middle ear. On the other hand, its vision is not very good and its eyes are not common among marsupials, since they are relatively small and have shaped pupils. vertical slit. To produce bass sounds they use an original vocal organ; unlike the typical mammalian vocal cords, which fold into the larynx, this organ is located in the soft palate and is called the velar vocal cords.

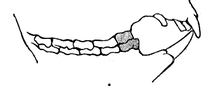

Koalas have undergone various adaptations to adapt to their diet based on eucalyptus leaves, which are of low nutritional value, high toxicity, and high in dietary fiber. The dentition of this animal is made up of the incisors and postcanines (a single premolar and four molars in each jaw), which are separated by a large gap (characteristic of herbivorous mammals). The incisors are used to grasp the leaves, which they then cut along the petiole with the premolars before passing them to the sharp-cusped molars, where they are ground into small pieces. They can store food in their pouches before they are ready to eat. chewed. The partially worn molars of middle-aged koalas are optimal for breaking the leaves into small particles, which promotes more efficient digestion by the stomach and absorption of nutrients by the small intestine, which digests the eucalyptus leaves. to provide most of the animal's energy. Sometimes they regurgitate food into their mouths for a second chew.

Unlike kangaroos and possums, which feed on eucalyptus, koalas are caudal fermenters (which occurs in the large intestine) and their digestive retention can last up to 100 hours in the wild, or up to 200 hours in captivity. This is possible thanks to the extraordinary length of its caecum (200 cm in length and 10 cm in diameter), proportionally the largest of all animals. This anatomy allows them to select which food particles to retain for longer fermentation and which to let through: large particles tend to pass more quickly, taking longer to digest. Although their lower GI tract is proportionally larger than in other herbivores, the koala gets only 10% of its energy gy through fermentation. Since they obtain a low amount of energy from their diet, their basal metabolic rate is half that of a typical mammal, although this can vary depending on the season and the sexes. They are able to conserve water in the body by passing relatively dry fecal balls rich in undigested fiber and storing water in the cecum.

Ecology and behavior

Its geographic range spans approximately 1,000,000 km² in 30 ecoregions. It extends across eastern and southeastern Australia, including the north east, central and south east Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria and south east South Australia. The koala was introduced in the vicinity of Adelaide and on several nearby islands, including Kangaroo and French Island. The Magnetic Island population represents the northern limit of its range. Fossil evidence indicates that its geographic range extended farther west to southwestern Western Australia during the Late Pleistocene. Their extinction in this area was probably caused by environmental changes and hunting by Aboriginal Australians.

In Queensland, populations are patchy and uncommon except in the south-east where they are numerous. In New South Wales they are only abundant in the Pilliga forests, while they are common throughout the state of Victoria. In the south they were extirpated (local extinction) in the 1920s and later reintroduced. Koalas can be found in habitats ranging from relatively open forest to woodland and in climates ranging from tropical to temperate. In semi-arid climates, they prefer riparian habitats, where nearby rivers and streams provide shelter in times of drought and extreme heat.

Diet and activity

Koalas are herbivores and although most of their diet consists of eucalyptus leaves, they can be found on trees of other genera, such as Acacia, Allocasuarina, < i>Callitris, Leptospermum and Melaleuca.

Eucalyptus leaves contain high levels of secondary metabolites (phenolic compounds and terpenes) that are usually lethal to most mammals. However, these marsupials have the ability to metabolize these xenobiotics. This can be explained by the two cytochrome P450 family 2C-specific monophyletic expansions (CYP2Cs) found in koalas. The function of cytochrome P450 plays a fundamental role in the detoxification during phase I of oxidative metabolism of a range of compounds, including xenobiotics.

Although they have the foliage of more than six hundred eucalyptus species in their range, they show a strong preference for only about thirty of them. They tend to choose species that are high in protein and low in fiber and lignin.. In addition, they select those leaves with fewer toxic secondary metabolites, thanks to the fact that they have a greater number of receptors in the vomeronasal organ and taste receptors such as TAS2R, which allow them to detect substances such as terpenes, phenols and glycosides, some of them they are toxic. Their preferred species are Eucalyptus microcorys, E. tereticornis and E. camaldulensis, which make up on average more than 20% of their diet. Despite their reputation as a picky eater, the koala is more of a generalist than other marsupial species, such as the giant glider. Since eucalyptus leaves contain a high water content, they do not need to drink often; their daily water turnover rate ranges from 71 to 91 ml per each kg of body weight. They also select for leaves with the highest water content, thanks to a duplication of the aquaporin 5 gene. Although females can meet their water needs by eating leaves alone, larger males require additional water inputs from the soil. or in the hollows of the trunks of trees. To eat, they hold on to a branch, holding on with their hind legs and one foreleg while with the other foreleg they tear the foliage. Small koalas can move near the end of a branch, but larger ones stay near the base of thicker ones. They consume up to 400 g of leaves per day. spread over four to six feeding sessions. Despite their adaptations to a low-energy lifestyle, they have few fat stores and need to eat frequently.

Because they get so little energy from their diet, they must limit their energy expenditure, so they only engage in active movement for about four hours a day and spend the remaining twenty hours asleep. They are predominantly active at night and spend most of their waking hours feeding. They usually eat and sleep in the same tree, where they usually stay for a day. On very hot days they may go down to the cooler part of the tree, which is cooler than the surrounding air, and cuddle up to the tree. tree to lose body heat without the need to pant. On warm days they may rest with their backs against a branch or lie on their stomachs or backs with their limbs dangling. During cold, wet periods, they curl up into a ball to conserve energy. On windy days, koalas look for thick, low branches to rest on. Although they spend most of their time in trees, they descend to the ground to move from one to the other, walking on all fours. They usually groom themselves using their hind legs, although they sometimes use their front legs or their mouths.

Sociability

They are asocial animals, spending only 15 minutes a day on social behaviors. In Victoria their home range is small and highly overlapping, while in central Queensland it is larger and less overlapping. The society of these animals appears to be made up of "residents" and "transients", made up mostly in the first case by adult females and by males in the latter. Resident males appear to be territorial and dominate other males with their larger body size. Alpha males tend to establish their territories near breeding females, while younger males behave subserviently until they mature and reach full body development. complete. Adult males occasionally venture outside their range or home range, maintaining their status. When a male moves to a new tree, it marks it by rubbing its pectoral gland against the trunk or a branch; they have also been observed occasionally urinating on the trunk. This territorial marking behavior likely serves as communication, and individuals are known to sniff the base of a tree before climbing. Scent marking is common during aggressive encounters. Pectoral gland secretions are complex chemical mixtures — about 40 compounds have been identified in one analysis—varying in concentration and composition depending on the season and the age of the animal.

Adult males communicate with loud, low-pitched roars consisting of snore-like inhalations and resonant exhalations that sound like grunts. These sounds are thought to be generated by vocal organs unique to this species. Due to their Low frequency, these roars can travel great distances through the air and vegetation. They emit them during any time of the year, but especially during the mating season, when they use them to attract females and possibly to intimidate other males. They also announce their presence to their neighbors when moving to a new tree. With these calls they indicate their body size and are able to exaggerate it, as females pay more attention to the roars of larger males. Females They also emit roars, although softer, as well as grunts, moans and screams. These calls are issued when in danger and to make defensive threats. Young koalas squeal when in danger. As they get older, the squeak becomes a kind of scream produced both when they are feeling distressed and to show aggression. When another individual climbs on it, it emits a low grunt with its mouth closed. Koalas display numerous facial expressions. When he growls, moans, or squeals, he curls his upper lip and folds his ears forward. During screaming they retract their lips and ears. Females move their lips forward and raise their ears when restless.

Agonistic behavior usually consists of bickering between individuals climbing or passing each other, sometimes leading to biting. Unfamiliar males may fight, chase, and bite each other. In extreme situations, a male may attempt to drive a smaller rival out of a tree. This involves the larger assailant climbing up and trying to corner the victim, who tries to quickly escape by dodging and climbing down the tree or moving to the end of a branch. The offender attacks by grabbing the victim by the shoulders and biting him repeatedly. Once the weaker individual is driven off, the victor roars and marks the tree. Pregnant or lactating females are particularly aggressive, attacking individuals that get too close. However, koalas generally tend to avoid aggressive behaviors that waste energy.

Reproduction and development

They are seasonal breeders, hatching from mid-spring through summer and early fall, October through May. Females in heat tend to hold their heads further back than usual and often suffer from tremors and spasms. However, males do not seem to recognize these signals and cases have been observed in which they mount females that are not in heat. Being much larger in size, males can force females to mate by mounting them from behind and, in extreme cases, even pulling the female out of the tree. The female may scream and fight vigorously against her suitors, but she will submit to a dominant or familiar male. The roars and screams they emit during mating can attract other males from the surrounding area, forcing the male to delay mating and fight off intruders; these fights can allow the female to assess which is dominant. It is common to see markings, scars, and cuts on older males, especially on the exposed parts of the nose and on the eyelids.

Ovulation is induced, that is, after intercourse, the ejaculated semen of the male induces the production of luteinizing hormone (LH) that causes ovulation in the female. The gestation period lasts 33-35 days and females typically bear a single young. Like all marsupials, young are born while still in the embryonic stage, weighing as little as 0, 5 and 2 g, although they already have relatively well-developed lips, shoulders, and limbs, as well as functional respiratory, digestive, and urinary systems. The newborn crawls into its mother's pouch to continue its development. Unlike most marsupials, the koala does not clean its pouch.

The female has two teats, and the young latch on to one of them to suckle during the entire period of its life in the pouch. The koala has one of the highest rates of milk energy production in relation to its body size shortest of all mammals; to compensate, the lactation period is extended to twelve months. At seven weeks of age, the head of the calf begins to grow in proportion to the body, pigmentation begins to develop, and its sex can be determined, since in males The scrotum can already be seen and in females the marsupium begins to develop. At 13 weeks, the pup weighs around 50g and its head has doubled in size, its eyes are beginning to open and fine fur grows on its forehead, neck, shoulders and arms. At 26 weeks the pup resembles an adult, is completely covered in fur and begins to poke its head out of the pouch.

As the young approaches six months of age, the mother begins to prepare it for its eucalyptus diet by predigesting the leaves and producing a fecal mush that the young eat from its cloaca; the composition of this porridge is very different from that of regular feces, more resembling the contents of the cecum and has a high concentration of bacteria. The young feed in this way for about a month, receiving a supplemental source of protein through this porridge while transitioning from a milk-based to a leaf-based diet occurs. It leaves the marsupial pouch for the first time at six or seven months of age, when it weighs between 300 and 500 g, and then begins to explore its new environment cautiously, clinging to its mother for support. At nine months he weighs more than 1 kg and develops his adult skin colour. After having definitively abandoned the pouch, it rides on its mother's back to move and learns to climb by clinging to the branches of trees. Little by little, it spends more time separated from its mother, weaning itself completely at 12 months., already weighing about 2.5 kg. When the mother becomes pregnant again, her bond with her previous offspring is completely broken and he behaves aggressively towards the newly weaned so that they separate and become independent from her.

Females reach sexual maturity around three years of age, at which time they can become pregnant. In contrast, males reach sexual maturity when they are around four years of age, although they can already produce sperm at two years of age. Although their pectoral glands are already functional at 18 months of age, males do not initiate their mating behavior. scent marking until they reach sexual maturity. Because the young have a long dependency period, females often breed every other year, although favorable environmental factors such as an abundant supply of high-quality food-producing trees are present. quality, they may reproduce every year.

Health and Mortality

They can live from 13 to 18 years in the wild, although males often live less than females due to their more dangerous behaviors. They often survive falls from trees and immediately climb back up, but are they give cases in which they can be injured or even killed, especially among inexperienced young or during fights between males. At around six years of age, their molars begin to wear down and their chewing efficiency decreases; over time the cusps of these teeth disappear completely, causing the animal to die from starvation.

Koalas have few predators; dingoes and large pythons may hunt them, while birds of prey such as the robust nynox or bold eagle may attack the young. They do not normally suffer from external parasites, except for ticks in coastal areas. They can suffer from scabies caused by the mite Sarcoptes scabiei and skin ulcers from the bacterium Mycobacterium ulcerans, although both ailments are rare. Internal and normally harmless parasites are also not common, among these are the cestode Bertiella obesa, usually in the intestine, and the nematodes Marsupostrongylus longilarvatus and Durikainema phascolarcti which are rarely found in the lungs. In a three-year study of nearly 600 koalas admitted to the Australian Zoo Wildlife Hospital in Queensland, 73.8% of the animals were infected with at least one parasitic protozoan species of the genus Trypanosoma, the most common of which was T. irwini.

They can be affected by pathogens such as Chlamydiaceae bacteria, which can cause keratoconjunctivitis, urinary tract infection, and reproductive tract infection. These infections are common in mainland populations, but do not occur in some island populations. Koala retrovirus (KoRV), belonging to the genus Gammaretrovirus, can cause Koala Immune Deficiency Syndrome (KIDS), a syndrome similar to HIV/AIDS in humans. The prevalence of KoRV in koala populations shows a trend extending from northern to southern Australia, with northern populations fully infected, while some southern populations (including Kangaroo Island) are free of this virus.

Conservation status

In 2016, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) included the koala on its Red List, classifying it as a vulnerable species due to "uncertainty about the relevant parameters of its population and the marked variation in population trends in its wide range of distribution. The overall rate of decline in population size over the past 18-24 years was estimated to be approximately 28% by the Scientific Committee on Threatened Species (2012), with a rate considerably influenced by severe depletion in regions most exposed to recent drought." In 2009 Australian lawmakers rejected a proposal to include the koala in the Biodiversity Conservation and Environment Conservation Act 1999. In 2012 the Australian government listed koala populations in Queensland, New South Wales and the Capital Territory as vulnerable in its national environmental legislation. Populations in Victoria and South Australia appear to be abundant, however the Australian Koala The Foundation argues that the exclusion of Victorian populations from protection measures is based on the misconception that the total koala population is 200,000, while they believe it is probably less than 100,000.

Australian aborigines hunted them for food. A common technique used to hunt them was to put a loop made of plant fibers at the end of a long, thin stick, in this way they could trap an animal high up in a tree, where they could not reach it by climbing up the trunk. Once caught in the lasso they killed it with a stone ax or a waddy, a kind of wooden mallet. Some tribes considered it taboo to remove the skin of the animal, while others believed that its head had a special status and kept it to bury it later.

In the early 20th century it was hunted in large numbers by European settlers, mostly for its thick, soft fur. It is estimated that more than two million pelts left Australia in 1924. Their pelts were used to make rugs, coat linings, muffs, and as linings on women's clothing. Mass culls took place in Queensland in 1915, 1917 and 1919, when more than a million koalas were killed with firearms, poison and traps. The popular outcry behind these massacres was probably the first large-scale environmental issue that prompted Australians to demonstrate. Novelist and social critic Vance Palmer wrote a letter in The Courier-Mail newspaper expressing popular sentiment:

The shooting of our harmless and lovable native bear is nothing less than barbarous... No one has ever accused him of spoiling the farmer's wheat, eating the squatter's grass, or even the spreading of the prickly pear. There is no social vice that can be put down to his account... He affords no sport to the gun-man... And he has been almost blotted out already from some areas.The hunt of our harmless and adorable native bear is nothing less than a barbarism... No one has ever accused him of ruining the wheat of the peasant, of eating the herb of the invading settler, or even of spreading the prickly. There is no bad social habit that can be charged on your account... It does not offer sport to the armed man... and has been almost exterminated from some areas.

Despite a growing social movement to protect native species, poverty caused by the 1926-28 drought led to the slaughter of another 600,000 koalas during an open hunting season in August 1927. In 1934 Frederick Lewis, then the Chief Game Inspector in Victoria, stated that the once abundant animal had been driven to near extinction in that state, suggesting that only between 500 and 1000 copies remained.

The first successful efforts to conserve the species began with the establishment of the Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary in Brisbane and the Koala Park Sanctuary in Sydney in the 1920s and 1930s. The owner of the latter park, Noel Burnet, became the first to achieve captive breeding of koalas, earning him a reputation as the foremost contemporary authority on this marsupial. In 1934, David Fleay, Curator of Australian Mammals at Melbourne Zoo, established the first wildlife enclosure. native in an Australian zoo, which included the koala, allowing him to carry out a detailed study of its diet in captivity. Fleay subsequently continued his conservation efforts at the Healesville Sanctuary and the David Fleay Wildlife Park.

Since 1870, koalas have been introduced around Adelaide and several nearby islands, including Kangaroo and French Island. Their numbers have increased considerably, but as the islands are not large enough to support large numbers, overgrazing became a problem. In the 1920s, Lewis began a large-scale relocation and rehabilitation program. scale to transfer koalas whose habitat had been fragmented or reduced to new regions with the intention of returning them to their former range. For example, in 1930-31, 165 individuals were transferred to Quail Island (Victoria) and, after a period of population growth and subsequent overgrazing of the eucalyptus trees on the island, in 1944 about 1,300 animals were released back into the islands. continental areas. The practice of moving koalas became common; Peter Menkorst, Victoria's state manager, estimated that between 1923 and 2006 some 25,000 animals were moved to more than 250 points in the state. Since the 1990s Various government agencies have attempted to limit their numbers through controlled culling, but criticism from both local and international has forced the continuation of the practice of transfer and sterilization instead.

One of the major human impacts on the environment for the koala is the fragmentation and destruction of its habitat. In coastal areas the main cause is urbanization, while in rural areas it is agriculture and the clearing of native forests for the manufacture of wood products. In 2000 Australia ranked fifth in the world for its deforestation rate, with 564,800 hectares being cleared, and according to Independent Australia in 2015 it was leading the way in deforestation and extinction species. The koala's range has shrunk by more than 50% since the arrival of Europeans, largely due to fragmentation of its range. habitat in Queensland. Its "vulnerable" status in Queensland, New South Wales and the Capital Territory means that developers in these regions should consider the potential impact on this species before undertaking any construction projects.. It must also be taken into account that koalas live in many areas p protected.

While urbanization can pose a threat to koala populations, koalas can survive in urban areas, provided there are sufficient trees, although they are subject to being hit by vehicles and attacked by domestic dogs, killing koalas. about 4,000 animals each year. In these cases, injured koalas are often taken to wildlife hospitals and recovery centers. In a 30-year retrospective study conducted at a New South Wales koala rehabilitation center, found that trauma, usually the result of a motor vehicle accident or dog attack, was the most frequent cause of admission, followed by chlamydial infections. Caregivers at these centers have special permits, but must release the animals back into the wild when they are well or, in the case of young, when they are old enough. As with most Australian wildlife, it is illegal to keep koalas as pets, both in Australia and elsewhere in the world.

One of the greatest dangers they face is forest fires, due to their slow movement and the flammability of eucalyptus trees. The koala instinctively seeks refuge in the upper branches, where it is vulnerable to intense heat and the flames Wildfires also fragment their habitat, restricting their movement and leading to population declines and loss of genetic diversity; dehydration and overheating can also be fatal. As a result, the koala is vulnerable to the effects of climate change. Climate change models in Australia predict warmer and drier climates, suggesting that the koala's range will shrink in the east and south moving towards more temperate and wetter habitats. Droughts also affect koala well-being. For example, a severe drought in 1980 caused many eucalyptus trees to lose their leaves, which subsequently caused 63% of the population of South West Queensland died, especially young animals which were excluded from main feeding grounds by the older, dominant koalas and subsequent population recovery was slow. Later this population declined by an estimated mean of 59,000 individuals in 1995 to 11,600 in 2009, a decline largely attributed to warmer conditions and resulting from the droughts that occurred between 2002 and 2007. Another negative forecast of climate change is the effect of rising atmospheric CO2 levels on the koala's food supply, as increased levels cause a reduction in proteins in eucalyptus trees and au the concentration of tannins in its leaves decreases, which reduces the quality of the practically only source of food for these animals.

Relationship with humans

History

The first written reference to the koala was recorded by John Price, a servant of John Hunter, Governor of New South Wales. Price found a "cullawine" on 26 January 1798 during an expedition to the Blue Mountains, although his find was not published for almost a hundred years later in the Historical Records of Australia. In 1802, the French explorer Francis Louis Barrallier found the animal when his two aboriginal guides returned from hunting bringing two koala paws with the intention of eating them. Barrallier preserved these appendices and sent them along with his notes to Governor Hunter's successor, Philip Gidley King, who in turn sent them to the English naturalist Joseph Banks. As with Price, Barrallier's notes were not published until 1897. An article on the first capture of a live "koolah" was published in The Sydney Gazette in August 1803. A few weeks later, James Inman, astronomer to the navigator and cartographer Matthew Flinders, bought a couple of samples to send to Joseph Banks in England, which he described as from an animal "somewhat larger than the waumbut" (wombat). These encounters prompted King to commission artist John Lewin to paint watercolors of the animal. Lewin painted three pictures, one of which later became an engraving reproduced in Georges Cuvier's The Animal Kingdom (first published 1827) and in various European works on natural history.

The first published image of a koala appeared in George Perry's natural history work Arcana in 1810. Perry named it the "New Holland Sloth" because he noted similarities. with the arboreal mammals from Central and South America of the genus Bradypus. His disdain for the koala, evident in his description of the animal, was typical of the prevailing early 19th century British attitude towards of the primitivism and rarity of the Australian fauna:

...the eye is placed like that of the Sloth, very close to the mouth and nose, which gives it a clumsy awkward appearance, and void of elegance... they have little either in their character or appearance to interest the Naturalist or Philosopher. As Nature however provides nothing in vain, we may suppose that even these torpid, senseless creatures are wisely intended to fill up one of the great links of the chain of animated nature...... the eye is situated as in the lazy, very close to the mouth and nose, which gives it a strange appearance, clumsy and lack of elegance... they have little in their character or appearance that may interest the naturalist or the philosopher. However, since nature does not provide anything in vain, we can assume that even these clumsy and meaningless creatures are wisely destined to fill one of the great links of the animated nature chain...

Botanist Robert Brown was the first to give a detailed scientific description of the koala in 1814, based on a female specimen captured near present-day Mount Kembla in the Illawarra region of New South Wales. Austrian botanical illustrator Ferdinand Bauer drew the animal's skull, throat, feet, and paws. However, Brown's work remained unremarked and unpublished, as his field books and notes remained in his possession until his death, when they were bequeathed to the Natural History Museum in London. These notes were not identified until 1994 (Bauer's watercolors were not published until 1989). British surgeon Everard Home included details of the koala based on testimony from explorer William Paterson, who had befriended Brown and Bauer while at New South Wales. Home, who in 1808 published his report in the journal Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society, gave the animal the scientific name Didelphis coola.

The British naturalist and popular artist John Gould illustrated and described this species in his three-volume work The Mammals of Australia, 1845-1863. and made it known both to other members of the Australian wildlife community and to the general British public. The comparative anatomist Richard Owen, in a series of publications on the physiology and anatomy of Australian mammals, featured a paper on the anatomy of the koala to the Zoological Society of London. In this widely cited work, he provided the first careful description of its internal anatomy and noted its general structural similarity to the wombat. English naturalist George Robert Waterhouse, Curator of the Zoological Society of London, was the first to correctly classify the koala as a marsupial in the 1840s. Waterhouse identified similarities between it and its fossil relatives Diprotodon and Nototherium , which had been discovered a few years earlier. Gerard Krefft, curator at the Australian Museum in Sydney, identified evolutionary mechanisms in his work by comparing the koala to its ancestral relatives in The Koalas. Australian mammals.

The first live koala arrived in Europe in 1881, purchased by the Zoological Society of London. According to what was reported by the society's solicitor, William Alexander Forbes, the animal died accidentally when a heavy sink lid fell on it from which it could not free itself. Forbes took advantage of this incident to dissect the fresh carcass of this female specimen, providing him with explicit anatomical details of its reproductive system, brain, and liver, parts not previously described by Owen, who only had access to preserved samples. Scottish embryologist William Caldwell, known in scientific circles to determine the reproductive mechanism of the platypus, he described the uterine development of the koala in 1884, using the new information to convincingly place the evolutionary period of the koala and monotremes.

Henry of Gloucester, son of King George V of the United Kingdom, visited Sydney's Koala Park Sanctuary in 1934 and was "extremely interested in 'bears'"; his photograph with Noel Burnet, founder of the park, and a koala, was featured in The Sydney Morning Herald. After World War II, when tourism to Australia began to increase and their animals began to be exported to zoos in other countries, the popularity of the koala increased throughout the world. This popularity led to photos being taken with these animals. various political leaders and members of royal families, such as Queen Elizabeth II of the United Kingdom, Prince Henry of Wales, Prince Naruhito and Princess Masako Owada, Pope John Paul II, US Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama, the Soviet President Mikhail Gorbachev, South African President Nelson Mandela, Australian Prime Minister Tony Abbott and Russian President Vladimir Putin.

Cultural Significance

It is a world-renowned animal and a major draw to Australian zoos and wildlife parks. He has appeared in advertisements, games, cartoons and stuffed animals. He is a significant contributor to Australia's tourism industry; a study carried out in 1997 showed that only in 1996 it represented an income of more than one billion dollars and some nine thousand direct jobs with an estimated income of 2.5 billion for the year 2000, figures that have increased since then. In 1997, half of the tourists visiting Australia, especially those from South Korea, Japan and Taiwan, visited zoos and wildlife parks and near the 75% of European and Japanese tourists ranked koalas at the top of their preferences for animals they wanted to see. According to biologist Stephen Jackson: "If I were to do a survey on which animal is most associated with Australia, it's a pretty safe bet that the koala would be marginally ahead of the kangaroo." Contributing factors to this enduring popularity include its infantile body proportion and teddy bear appearance.

The koala appears in Dreamtime stories and Australian Aboriginal mythology. The Tharawal people believed that this animal helped row the boat that brought them to the mainland. Another myth tells how a tribe killed a koala and used its long intestines to create a bridge for people from other parts of the world; this narrative highlights the koala's status as a game animal in Aboriginal culture and the length of their intestines. Several stories tell of how they lost their tail; in one, a kangaroo cuts it off to punish them for being lazy and gluttonous. Tribes in Queensland and Victoria considered it a wise animal and sought its advice. Bidjara-speaking people believed that koalas were responsible for turning barren lands into lush forests. They are often depicted in petroglyphs, though not as often as other species.

Early European settlers in Australia considered it a prowling, sloth-like animal with a "fierce, menacing gaze". In the early 1900s XX, the koala's reputation became more positive, largely due to its increasing popularity and its appearance in several well-known children's stories. It appears in Ethel Pedley's book Dot and the Kangaroo (1899), in which he is depicted as the "amusing native bear". Artist Norman Lindsay depicted a more anthropomorphic koala in The Bulletin magazine strips, which began in 1904; this character also appeared as Bunyip Bluegum in Lindsay's 1918 book The Magic Pudding. Although perhaps the most famous fictional koala is Blinky Bill, a character created by Dorothy Wall in 1933 who appeared in several books and has been the subject of films, television series, postage stamps, stuffed animals and a 1986 environmental song by Australian country musician John Williamson. The first Australian postage stamp featuring a koala was issued by the Commonwealth in 1930. A television advertising campaign for Australia's national airline, Qantas, which began in 1967 and ran for several decades, featured a live koala (voiced by actor Howard Morris) complaining that Australia had too many tourists and ended by saying "I hate Qantas"; this campaign was once ranked as one of the greatest television commercials of all time.

It is Queensland's state emblem for wildlife. The song "Ode to a Koala Bear" appears on the B-side of the 1983 Paul McCartney and Michael Jackson single Say Say Say. A koala is the main character in the 1980s cartoon series The Kwicky Koala Show by Hanna-Barbera and Noozles by Nippon Animation. There are numerous sweets in the shape of koalas, and Dadswells Bridge in Victoria has a tourist complex in the shape of a giant koala. The Queensland Reds rugby team have a koala as their mascot. There are numerous coins featuring koalas, such as the Australian "Platinum Koala", which shows the animal on the reverse and Queen Elizabeth II on the obverse.

As a counterpart to this docile herbivore, contemporary Australian folklore created the drop bear, a hoax depicting a predatory, carnivorous version of the koala. This imaginary animal is generally talked about in fantastic stories designed to scare tourists in rural towns and described as unusually large and vicious animals that dwell in the treetops and attack unsuspecting people or other prey passing below., falling on them.

Contenido relacionado

Glycolipid

Campylobacter

Carex