Peruvian Literature

Peruvian literature is understood as the literary manifestations produced by authors of that nationality, from pre-Hispanic traditions to the present, which includes literature from Cuzco, Arequipa, Puno, Amazonia and other regions of the territory of Peru, and which has achieved greater brilliance in the 20th century with indispensable names for universal literature, such as the poet César Vallejo or the novelist Mario Vargas Llosa. Belonging to the canon of the chroniclers of the Indies is more commonly accepted than other paraliterary manifestations, such as Peruvian children's literature or Peruvian science fiction literature.

Pre-Hispanic Andean tradition

The literary production of the pre-Hispanic period in the central-Andean territory (which covers territories of the current republics of Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and Chile), is especially linked to the Inca Empire, being its main vehicle of transmission the language Quechua or runa simi, which the Incas imposed as their official language. The chroniclers of the conquest and the colony have attested to the existence of a Quechua literature, which was transmitted orally and which is usually divided into courtly and popular.

- The court literature, so called for having performed in the court of the incas, was the official literature, whose execution was entrusted to the educators or teachers and to the quipucamayos or librarians, who used the nemotechnic system of the quipus or nested cords. Three were the main genres they cultivated: epic, didactic and dramatic.

- The epic genre is represented by the poems that expressed the cosmovision of the Andean world (mitos de la creación, el diluvio, etc.), as well as those that related the origin of the incas (the legends of the Ayar brothers, of Manco Cápac and Mama Ocllo, etc.).

- The teaching genre covered fables, apologists, proverbs and stories, examples of which have been modernly collected by various scholars.

- The dramatic genre, which, to say of the Inca Garcilaso, covered comedies and tragedies (obviously seeking their equivalents in Western culture). They were actually theatrical performances where dance, singing and liturgy were mixed. It is alleged that the famous drama Ollantay, whose written version dates from the colonial era, would have a fundamental core of incaic origin and a series of subsequent interpolations straightened to amoldar it to Hispanic theater.

- Popular literature is the one that spontaneously arose in the village and in the countryside. It massively encompasses the lyric genre, i.e. poetic compositions that were united to music and dance, and that were usually intonated in large coral masses, altering men and women. These manifestations were part of what to do everyday. Funerals, parties, nuptists, fights, wars, etc. were framed in a ritualization expressed through art. There are two main manifestations:

- The harawi, song of various types (of love, of repentance, of joy, etc.). He had an intimate character and was in charge of an aeda, called harawec or haravicu. In the colonial period he derived in the Huayno and the Yaravi.

- The Haylli, hymn of joy, was intonated at religious feasts or in celebrations of triumphs.

Many of these creations have survived to our days in a delayed manner, embodied in the works of the first chroniclers (the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega recovers Quechua poetry, while Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala recounts the myth of the five ages of the world).

Indigenous literature was unknown or relegated until the XX century. Its inclusion in the official canon was slow. Already in his thesis The character of the literature of Independent Peru (1905), José de la Riva Agüero y Osma considered "insufficient"; the Quechua tradition to consider it a predominant factor in the formation of the new national literary tradition. Subsequently, Luis Alberto Sánchez recognized certain elements of tradition and their influence on later tradition (in authors such as Melgar) to base his idea of mestizo or criolla literature (daughter of two sources, one indigenous and the other Spanish), for which he consults sources in the colonial chronicles (Pedro Cieza de León, Juan de Betanzos and Garcilaso).

The real opening to the pre-Hispanic tradition arose in the first decades of the XX century thanks to the work of literary scholars and anthropologists who compiled and rescued myths and oral legends. Among them, Adolfo Vienrich stands out with Tarmap pacha huaray (Quechua lilies, 1905) and Tarmapap pachahuarainin (Quechua fables, 1906); Jorge Basadre in Inca literature (1938) and Around Quechua literature (1939); and the anthropological and folkloric studies of José María Arguedas (in particular, his translation of Dioses y hombres de Huarochirí). More contemporary works include Martín Lienhard (The voice and its trace. Writing and ethnic-cultural conflict in Latin America. 1492-1988, 1992), Antonio Cornejo Polar (Writing on the air Writing in the air: essay on socio-cultural heterogeneity in Andean literatures. 1994), Edmundo Bendezú (Quechua Literature, 1980 and Other Literature, 1986) and Gerard Taylor (Rites and traditions of Huarochirí. Quechua manuscript of the XVII century, 1987; Quechua stories from Jalca, 2003).

Bendezú affirms that Quechua literature has been constituted, since the conquest, in a marginal system opposed to the dominant one (of Hispanic vein) and postulates the permanent existence and cover of a tradition of four centuries. He speaks of a great tradition (& # 34; enormous textual mass & # 34;) marginalized and left aside by the Western scriptural system, since this & # 34; other & # 34; Literature is, like Quechua, fully oral.

Cologne

The term colonial literature (or colonial literature) refers to the state of the territory of Peru in the XVI to the XIX century, dependent on the Spanish crown and politically organized as a Viceroyalty.

Literature of Discovery and Conquest

With the Spanish conquest, the Castilian language (misnamed Spanish) and European literary tendencies arrived in Peru. A process began that over time would give rise to a mestizo or Peruvian literature, although initially it accused of a Hispanic pre-eminence.

Francisco Carrillo Espejo has coined the term discovery and conquest literature, which designates the period that encompasses all the works written during the process of discovery and conquest of Peru, which began in 1532 in Cajamarca with the capture of the last Inca, Atahualpa, and ends with the dismantling of the Inca Empire. The literature of this period, although not necessarily written during this time frame, does relate to the events that took place before or during it.

The first literary manifestations were the couplets recited by the conquerors; An example is the famous copla written by a soldier during Pizarro's second trip, complaining to the governor of Panama about the hardships they suffered:

Well, Mr. Governor,

Look at him completely,

that there goes the collector

And here's the butcher.

Then came chronicles, discovery letters, and relationships. Particularly, the chronicles constitute an interesting literary genre that mixes history, the literary essay and the novel. The first chronicles, written by the soldiers and secretaries of the military expeditions, have a rough and dry style. Later, other better worked works appeared, such as that of Pedro Cieza de León (1518-1554), author of the Crónica del Perú, divided into four parts: First part of the Crónica del Perú, The Lordship of the Incas, Discovery and Conquest of Peru and the Civil Wars of Peru, which constitute the first major project of a global andean history. Due to this, some consider Cieza as the first historian of Peru. Finally, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega, mestizo, son of a Spanish conquistador and an Inca noblewoman, published at the beginning of the XVII century his Comentarios reales de los Incas, a work that exceeds the requirements of a simple chronicle to become a literary masterpiece, the first written by a Hispanic-American mestizo.

The critic Augusto Tamayo Vargas has divided the chroniclers into Spanish, indigenous, mestizo and criollo.

Spanish chroniclers

These are divided into two groups: chroniclers of the conquest and chroniclers of the colonization. The latter is further subdivided into pre-Toledo, Toledo and post-Toledo.

Chroniclers of Conquest

- Cristóbal de Mena

- Francisco de Jerez

- Pedro Sancho de la Hoz

- Miguel de Estete

- Pedro Pizarro

- Diego de Trujillo

- Alonso Borregán

Chronicles of colonization

- Pretoledanos

- Pedro Cieza de León

- Juan de Betanzos

- Agustin de Zárate

- Francisco López de Gómara

- Bartolomé de las Casas

- Cristóbal de Molina “the Chilean”

- Diego Fernández de Palencia “el Palentino”

- Fray Gaspar de Carvajal

- Toledanos

- Juan Polo de Ondegardo

- Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa

- Postoledanos

- Miguel Cabello Valboa

- Father Martin de Murúa

- Fernando de Montesinos

- Father José de Acosta

- Fray Reginaldo de Lizárraga

- Father Bernabé Cobo

Indigenous chroniclers

Three names are especially mentioned among indigenous, native, or Indian chroniclers:

- Titu Cusi Yupanqui, one of the incas of Vilcabamba who in 1570 wrote a Relation of how the Spaniards entered Peru and the subcess that Manco Inca had in the time between them lived.

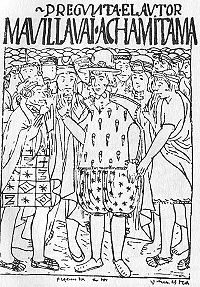

- Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, author of an original illustrated work: The First New Coron and Good Governance (sic), written between 1585 and 1615, and published only in 1936. In it he presents the process of destruction of the Andean world (due to the pride of the incas or fails in communication with the Spanish), trying to explain and present an alternative to the chaotic reality of his time.

- Juan de Santa Cruz Pachacuti Yamqui Salcamaygua, belonging to the lineage of the collaguas, is the author of a Relationship of Antiquities of This Piru Kingdom, written about 1620 or 1630, and published in 1879. Use to express yourself a Spanish rudimentary, strongly quechuted.

Half-Blood Chroniclers

- Blas Valera (1545-1597), a natural Jesuit religious of Chachapoyas, whose History of the Incas It was used by many Spanish chroniclers and even the same Inca Garcilaso and which apparently was lost in a fire in Cadiz, during a war between Spanish and English.

- Cristóbal de Molina “the cuzqueño” (1529-1585) clergy and chronist who for a long time believed to be mixed, but in reality was a natural Spanish of Andalusia, However, it was composed both with the Andean culture that can be considered a cultural mestizo. His main work is a Relation of fables and rites of the Incas.

But undoubtedly the most important mestizo chronicler is Inca Garcilaso de la Vega (1539-1616), considered the "first biological and spiritual mestizo of America" , or in other words, the first racial and cultural mestizo in America, since he knew how to assume and reconcile his two cultural heritages: the indigenous American (Inca or Quechua) and the European (Spanish), attaining great renown at the same time. intellectual. He is also known as the "prince of the writers of the New World", since his literary work stands out for his great command and command of the Spanish language. In his masterpiece, the Real Comments of the Incas , published in Lisbon in 1609, Garcilaso expounded on the history, culture, and customs of the Incas and other peoples of ancient Peru. For many critics it is the song of deed of Peruvian nationality, which is forged precisely with the fusion of two heritages, the native and the Spanish. Garcilaso is also the author of La Florida del Inca (Lisbon, 1605), which is an account of the Spanish conquest of Florida; and the Second part of the Royal Commentaries, better known as the General History of Peru (Córdoba, 1617), published posthumously, where the author deals with the conquest and the beginning from the colony. The Inca Garcilaso is justly considered the first writer of Peru.

Creole chroniclers

Among the Creole or American chroniclers (born in America to Spanish parents) who wrote about Peru, the following stand out:

- Pedro Gutiérrez de Santa Clara, native of Mexico, author of a History of wars more than civilians in the Kingdom of Peru.

- Augustinian father Antonio de la Calancha (1584-1654), native of La Plata and author of the Moralized body of the order of St. Augustine in Peruwhich contains valuable information from the pre-Hispanic past.

Other chroniclers

It is also worth mentioning the Italian Jesuit Father Giovanni Anello Oliva (1572?-1642), who lived more than 40 years in Peru, and was the author of a History of the kingdom and provinces of Peru and lives of illustrious men in the Society of Jesus of the province of Peru, whose first part is a historical introduction entitled: History of the kingdom and provinces of Peru, its Incas, kings, discovery and conquest by the Spanish of the crown of Castile.

Literature from the beginnings of the Viceroyalty

Important cultural milestones were the foundation of the Royal and Pontifical University of San Marcos de Lima on May 12, 1551 by Royal Provision of Carlos I of Spain and V of Germany, the first in America, and the installation in Lima of the first printing press in South America, that of Antonio Ricardo from Turin in 1583, institutions that promoted the early intellectual development of Peruvians.

The first book published in the city of Lima is the Christian Doctrine and Cathecism for the Instruction of the Indians (1584) by the printer Antonio Ricardo, which properly inaugurates the idea of Peruvian literature. This first catechism is published in Spanish, Quechua and Aymara. During previous decades, the system of reductions had already been established as a result of the reforms of Viceroy Francisco de Toledo (1569-1581) that separated colonial society into two republics, the Republic of Indians and the Republic of Spaniards (this is the period in which the greatest amount of extirpation of idolatry was carried out). The Laws of the Indies were also promulgated, which established the following:

“that is not printed, nor seen Art, nor Vocabulary of the language of the Indians, without being approved conforming to this law”; “that the profane and fabulous books are not reflected in the Indias. For from taking to the Indian books of Romance, who deal with profanous matter, and fabulous and fined stories follow many inconveniences (...) that no Spanish, nor Indian read them”; “that the books of Hereges be collected, and prevent their communication. Porqve the Hereges Pirates with the cause of the prey and rescues have had some communication in the Ports of Indias, and this is very damaging to the purity with which our vassals believe and have the Santa Fé Catolica for heretical books and false propositions, which spread and communicate to ignorant people. ”Indian Laws, Book I, Title XXIVcolor

These two factors determined that the initial literary production in the Colony was limited to circles of mainly Hispanic influence, produced in large cities by children of Spaniards (Spanish Americans). Literature is cultivated in enlightened circles, closely linked to the Church (which provides education among the social elites, since all the schools and convictories were run by religious orders). From the Church it is precisely Father José de Acosta, who pays more attention to the American world since, together with his religious and theological reflections, we find a clear concern for the geography and physiology of the natural peoples of Peru. Acosta represents a moment in which Renaissance aesthetic standards are still present on the literary scene. In 1586 he published Peregrinación de Bartolomé Lorenzo, in 1588 De Natura Novi Orbis et De Promulgation Evangelii apud barbaros, sive de Procuranda indorum salute (Of the nature of the new world...) and in 1590 his best-known work: Natural and Moral History of the Indies.

Classicism (mid-16th and early 17th century)

The literature of the so-called Spanish Golden Age is also reflected in Spanish America, especially in the field of lyrical and epic poetry. It is an erudite literature, of refined forms, adhered to the classic molds (classicism). The most relevant authors who developed in Peru under this trend are the following:

- Diego de Hojeda (1571?-1615), a Sevillian poet, ordained a priest in Peru in 1591, is the author of The Cristiada (1611), first epic-mystical poem written in America, in octaves.

- Clarinda, pseudonym of the author or author of Speech in poetry parlor, poem in stews, which appeared in the Antarctic paranaso (1608) by Diego Mexía de Fernangil.

- Amarilis, pseudonym of the author or author of the Epistle to Belardo, written in silva, directed to Lope de Vega and that he reproduced in The Filomena (1621).

- Diego Mexía de Fernangil (1565?-1634), author of the first part of Antarctic paranaso (1608). The second part was not published and remained unpublished until the centuryXX..

Baroque style (17th century)

Following the trend dictated from Europe, Peruvian literature adopts the baroque style (conceptismo and culteranismo). Literary language tends to be overloaded with many stylistic devices and erudition is displayed. The top figure of Peruvian baroque style was El Lunarejo.

- Juan de Espinoza Medrano called "El Lunarejo" (1630?-1688), clergy, preacher, writer and humanist mestizo, born in the village of Calcauso (Apurímac). Author of religious, sermon and dramatic pieces Apologetic in favor of D. Luis de Góngora, prince of the lyric poets of Spain (1662), brilliant defense of the lyrics of the Spanish poet, summit of culteranism. Posthumously a selection of his sermons was edited under the title The ninth wonder (1695).

- Juan del Valle and Caviedes (1652 or 1654-after 1696), satirical poet and ribumbrist, born in Spain, but who lived mostly in Peru. It highlights its festive and satirical poetry, through which it makes a harsh criticism of the social environment. He also cultivated mystical poetry and repentance. His poetic work was compiled and edited long after his death, under the title of Diente del Parnaso.

We can also mention Lorenzo de las Llamosas (c.1665-c.1705), who after a few years in the Viceroyalty of Peru, traveled to Spain where he carried out activities in the King's Court, as a soldier and at the same time as the author of plays and didactics.

Frenchification and Neoclassicism (18th century)

In the second half of the XVII century, literature in Europe, under the influence of French letters, tended to return to the classic molds, although in the Spanish colonies the baroque style continued to predominate. However, at the beginning of the XVIII century, coinciding with the establishment of the Bourbon dynasty in Spain, Spanish-speaking writers tended to to “frenchify”. Literary Academies arose, imitating those of France, such as the so-called Palacio Academy founded by the Viceroy of Peru Marqués de Castell dos Rius (1707-1710). Among the academics of the Palace, the following stand out:

- Luis Antonio de Oviedo and Herrera, Count of the Farm (1636-1717), poet and theatrical author, author of the poems: The Life of Santa Rosa (1711) and Sacred Poem of Passion (1717).

- José Bermúdez de la Torre y Solier (1661-1746) Limeño poet, author of the poem Theme on the island of Calipso; he was also jurisconsult, as well as rector of the University of San Marcos de Lima.

- Pedro Peralta and Barnuevo (1664-1743), Limeño poet, scholar and scientist, the most outstanding literary figure of the first half of the centuryXVIII. His work that covered various fields of knowledge, being the author of tragedies and sainetes that can be considered the precursors of coastalism. Among his works he highlights Lima Founded (1732), epic poem of great breath, in ten songs, 1183 real octaves and a total of 9464 verses endecasylabos. However, it is their theatrical works that have aroused more the interest of modern criticism.

Neoclassicism broke out in the second half of the XVIII century and progressively displaced Baroque style. It is a return to the norms of classicism, in opposition to the ornate style of baroque, as well as a tendency towards a pedagogical attitude. This movement developed together with the expansion of liberal ideas that emerged in France, which would have such an influence on the development of the separatist revolution in Latin America.

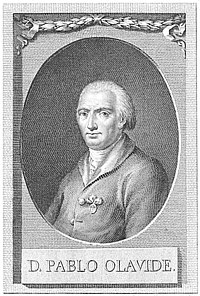

The most conspicuous figure of literary Frenchism in the second half of the XVIII century was Pablo de Olavide (1725-1803), writer, translator, jurist and politician, born in Lima, but who developed his career in Spain. His house in Madrid became a prominent center for cultural gatherings. Influenced by the French Enlightenment, he initially professed liberal ideas. Accused of heresy, he was imprisoned by the Inquisition. Reconciled with religion, he published The Gospel in Triumph (1797); Christian poems; and Spanish Psalter (1799). Already in the XX century, the works of his Frenchified period, of dramatic and narrative genre, were exhumed, the latter being the one that has aroused the interest of modern critics, since they are short novels, which would make Olavide a precursor of said literary genre.

While in Peru, Creole poets and satirical writers, close to costumbrismo, developed at that time:

- Fray Francisco del Castillo Andraca (1716-1770), known as "The Blind of La Merced", friar, playwright and poet, undoubtedly the best theatrical author of the colony and among whose works stand out The Conquest of Peruone of the first to offer a critical perspective of the conquest of Peru; All the wits out there.; Mitridates, king of the Ponto; the intermés From justice and litigants. This friar belonged to the Order of Merced and should not be confused with the Jesuit priest Francisco del Castillo S.J. (1615-1673), who also lived and worked in Lima, but a century earlier.

- Alonso Carrió de la Vandera (1714 or 1716-1783), who under the pseudonym of Concolorcorvo, wrote the Lazarillo of blind walkers, book that for quite some time was mistakenly attributed to Calixto Bustamante Carlos Inca and which deals with a journey carried out between Lima and Buenos Aires.

- Esteban Terralla and Landa, a satirical poet who used the pseudonym Simon Ayanque to publish your book Lima inside and outside (1797).

At the end of the XVIII century and coinciding with the end of the mandate of Viceroy Manuel Amat y Juniet, it was represented in the steps of the cathedral of Lima a drama, the Drama of the basins: veteran and inexperienced, which is a ruthless criticism of the government and the person of this viceroy, particularly his love affair with La Perricholi. The text has been rescued by the literary critic Luis Alberto Sánchez.

Emancipation (18th and 19th centuries)

The last period of colonial literature spans from the late 18th century to the early XIX, at this time the idea of freedom arose and the events that marked an influence are: The French Revolution that occurred in 1789 in addition to the Independence of USA in 1776. It was developed in a context of the Revolution of Túpac Amaru II in 1780 and this movement will conclude with the uprising of the Peruvian people due to the dictatorship of Simón Bolívar; and the Proclamation of Independence on July 28, 1821.

In the style of the French encyclopedists, the editors of Mercurio Peruano, the first great American magazine, who group together in the so-called Society of Country Lovers, stand out. Among them, Hipólito Unanue, Toribio Rodríguez de Mendoza, José Baquíjano and Carrillo, among others, stand out.

The themes used in this literature were: freedom, the goal of all indigenous people; the homeland, anti-Spanish and separatist; and indigenous sentiment.

In the field of poetry, Mariano Melgar (1791-1815) from Arequipa stands out, in whose verses romanticism is prefigured and shows a mix between cultured poetry and indigenous popular songs. Although his work falls more within the Republican era, and consists of Letter to Silvia (1827) and Poems (1878). He joined the independence revolution in 1814 and was shot. This poet was nicknamed "The precursor of literary Romanticism in America" and "Representative of the first authentic moment of Peruvian literature".

Another representative of Emancipation poetry is José Joaquín Olmedo (1780-1847), born in Guayaquil when it belonged to Peru. He was a deputy before the first Congress of the Republic of Peru and Plenipotentiary Minister of Peru in England. His fundamental poem is Ode to the victory of Junín , epic verses of neoclassical style that sing of the triumph obtained by Bolívar in the battle of Junín.

In the field of political literature, the tribune José Faustino Sánchez Carrión (1787-1825), defender of the republican system of government and author of the Letter of the Solitaire of Sayán, stands out.

It is also necessary to mention the Lima clergyman José Joaquín de Larriva (1780-1832) poet, writer and journalist, nicknamed the “lame Larriva”. A satirical and very scathing writer, according to Porras Barrenechea he was the "first comic poet" of Peru. Currently he is remembered more for the letrillas he wrote against the Liberator Bolívar, although in his time he was very popular and celebrated for his funeral and laudatory orations, and his newspaper articles, in addition to his poetic improvisations. He is considered a precursor of Peruvian literary costumbrismo.

Republic

19th century

The first literary currents of independent Peru were costumbrismo and romanticism. Already in the last stretch of the century, realism developed.

Customs

Costumbrismo was a literary current whose cultivators paid more attention to the customs of the people, both to celebrate them, as well as to criticize or ridicule them, through diverse genres (comedies, letrillas, sainetes, etc.). In Peru it begins around 1830, coinciding with the founding period of the Republic and lasts until the 1850s.

Two satirical poets and comic playwrights belong to the Peruvian costumbrista period, both from Lima, but with opposite spirits:

- Felipe Pardo and Aliaga (1806-1868). The Peruvian reality through its comedies and coastal articles was seriously examined and judged; among the latter it is more celebrated and remembered A journey, better known as The Journey of the Boy Goyito. Poetry highlights his letrillas and epigrams, the most reproduced: "The Jet of the Warrior" and "My Son in His Days." In the dramatic field he wrote only three comedies: Fruits of education, An orphan in Chorrillos and Don Leocadio and the anniversary of Ayacucho. He was a severe critic of popular customs he considered barbaric and repellent. He also directed his criticism of the habits of politicians, the lack of civics and the personalistic ambition of the rulers.

- Manuel Ascencio Segura (1805-1871), considered the greatest national playwright of the centuryXIXIt's the one who best portrays the popular types of Lima. While Felipe Pardo was a man of aristocratic ideas and defender of the Spanish colony, Segura represented the democratic values of the new Peruvian society, which is reflected in the Creole taste of his coastal comedies. He is the author of 17 plays, among which stand out Ña Catita, The Pepa, Sergeant Canuto, The saya and the mantle, Lances of Amancaes, The three widows. In the field of the lyrics his poems are very remembered: "To the girls" and The Pelimuerte.

From this period it is also important to highlight the following authors:

- Narcissus Aréstegui (1818 or 1820-1869), cuzqueño, author of the novel Father Horan (1848), considered the first novel of Peruvian literature and one of the first South American novels in Spanish. It is also considered as one of the major precursors of indigenism in Peru.

- Flora Tristan (1803-1844), a Peruvian-French writer, born in Paris, author of Pilgrimages of a pariah, a diary of his journey through Peru (between 1833 and 1834) where he came claiming the paternal heritage. It is a fundamental book to know closely the avatars of the incipient Peruvian Republic, whose practices and customs were carefully analyzed by the author. He also wrote the novel Mephis.

- Manuel Atanasio Fuentes, known as The bat (1820-1889), he wrote Bat fins (3 vols., 1866) and Lima: historical, descriptive, statistical and customs notes (1867, in Spanish, French and English editions).

Close to costumbrismo is the work of Ricardo Palma (1833-1919), a writer from Lima, author of the famous Peruvian Traditions, the best-known work of the century, in which through a series of traditions —a genre invented by him, which combines elements of history with his own fables—, narrates the history of Lima and Peru during the Inca, colonial and republican eras. Written between 1860 and 1914, a definitive edition was compiled by Angélica Palma, the traditionist's daughter, in six volumes (1923-1925).

Romanticism

Romanticism, coming from Europe, arrived in Peru late, around the 1840s, and lasted for the rest of the century, although it declined after the War of the Pacific, to give way to Realism. The texts of the Peruvian romantics were, in general, artificial and abused sentimentality. The plays frequently cultivated the same sentiment and implausibly exaggerated the entanglements; although some were successful at the time, today they are forgotten. Two representatives of Peruvian romanticism, however, have survived literaryally, due to the quality of their works: Ricardo Palma and Carlos Augusto Salaverry, belonging to the so-called bohemia generation.

- Ricardo Palma (1833-1919), of which we have already mentioned its celebrations Peruvian traditions. He cultivated other genres, such as poetry, highlighting in this field his poems: Poetry, Youth, Harmonies, Passion, Cantarcillos, Religious, Nieblas and above all Verbos and gerundiosworks that express romantic feelings or a mock attitude to certain aspects of reality. Literary critique is your book The bohemia of my time, autobiography and relationship of romantic writers. He also wrote a philological work: Lexicographic ballots. Theatrical work is also preserved from his pen: Rodil.

- Carlos Augusto Salaverry (1830-1891), considered the best Peruvian lyric poet of the centuryXIX, was the son of Felipe Santiago Salaverry, the leader of the first years of the Republic who died shot in 1836. His poetic work gathers in four books: Diamonds and pearls, Albors and flashes, Letters to an angel and Mysteries of the tomb. His poetry is singularized by the melancholic sweetness of his passionate soul, by the elegant pessimism of his attitude to life and the colourful emotion that encourages his intimacy torn apart. His poem “Remember Me” (I insert Letters to an angel) is infallible in all poetic anthology.

The following poets, writers and playwrights also belong to romanticism:

- Manuel Nicolás Corpancho (1830-1863), limeño, author of the drama The Cross Poet, praising in your time and currently forgotten. He died during a fire on the ship he travels in the Gulf of Mexico, when he returned from a diplomatic mission.

- José Arnaldo Márquez (1832-1903), Limeño, representative of Peruvian romantic poetry on its philosophical and social side. He was able to harmonize the individualistic romantic sentiment with the humanitarian concerns of his time and a forerunner adherence to socialist ideals. He was also an essayist, teacher, journalist, translator, diplomat, military and traveler.

- Luis Benjamín Cisneros (1837-1894), limeño, author of the drama Alfredo el Sevillano; novels: Love child: romantic toy, Julia or life scenes in Lima and Edgardo or a young man of my generationand lyric works: To the death of King Alfonso XII, Aurora and love and Free wings (this last posthumous compilation).

- Clemente Althaus (1835-1881), Limeño, son of a German officer arrived at the time of independence. Among his works are: Poetry several, Poetic works, Patriotic poetry, Antioco (drama). It was also highlighted as a translator.

- Acisclo Villarán (1841-1927), Limeño writer, founder of the Literary Club (1875) who later became the Ateneo de Lima. Author of a fruitful and versatile work, of which we highlight: The triumph of Peru, The crown of laurels, The priest of Locumba, The warrior of the century, Nieblas and auroras, Republican silhouettes, Poetry in the Empire of Incasetc.

- Pedro Paz Soldán y Unanue (1839-1895), Limeño writer, known for his pseudonym Juan de Arona. Author of poetry and comedy, was also essayist, translator and philologist, his most remarkable work being the Dictionary of Customs (1883-1884).

Realism and naturalism

After the War of the Pacific (1879-1883) there was a reaction against romanticism, led by the intellectual Manuel González Prada (1844-1918), who cultivated a poetry that, due to its aestheticizing and the introduction of new metric forms was a clear precursor to modernism. Among his prose works, it is worth mentioning: Pájinas libres and Horas de lucha, books in which he makes a furious criticism of the political class, responsible, according to him, for the war catastrophe. Neither are the religious institutions and the literati of his time spared from his darts. His hypercritical position in the field of ideas and literature earned him not a few enemies and got him into various journalistic controversies.

Realism was also developed, in a rather tenuous way, in the novel, which took off from then on in Peru.

A striking feature of this period is the rise of a group of women writers. Many of them—having lost their spouses and older children in the war with Chile—had to earn a living for themselves, and cultivated their literary vocation through social gatherings. The main one was that of the Argentine Juana Manuela Gorriti, in which social problems and the influence of European forms were discussed. They wrote novels that in a way can be described as realistic. Such is the case of:

- Mercedes Head of Carbonera (1845-1909), born in Moquegua, was the initiator of the Peruvian realistic novel. He wrote six novels of social content and critical intent, being the most successful White Sun (1888), The consequences (1890) and The Conspirator (1892). He also wrote numerous articles and essays published in the press, on literary and social issues; in particular he advocated for the emancipation of women, so he counts among the first feminists of Peru. He was misunderstood in his time, being the target of criticism by male authors such as Juan de Arona and Ricardo Palma. This led him to isolate. In case it was little, she began to suffer the sequelae of a syphilis that her own husband, being held in a asylum, where she died.

- Clorinda Matto de Turner (1852-1909), novelist, traditionist and journalist, cuzqueña, precursor or founder of literary indigenism. Author of Cuzqueña traditions and novels Birds without nest (1899), Indole (1891) and Inheritance (1893). The most outstanding and controversial of his works is Birds without nestwhere it exposes the situation of the indigenous who suffers the abuses of religious and political authorities. Although its technique and style are deficient, the work conceived the interest not only in Peru, but in America and Europe.

- Maria Nieves and Bustamante (1861-1947), a native of Arequipa, is the author of the historical novel Jorge, the son of the people (1892), set in the civil war of 1856-1858, is an epic song that highlights the warrior spirit of the people of Arequipa.

20th century

Modernism

Modernism developed in Peru from the poem «To love» by Manuel González Prada, published in the newspaper El Comercio in 1867, where the author fuses a set of poetic genres from Europe, resulting in the triolet. This tendency, the result of the cosmopolitanism that Peru lived, soon developed in other parts of Latin America: in Cuba with José Martí; in Nicaragua with Rubén Darío; in Argentina with Leopoldo Lugones; in Uruguay with Julio Herrera and Reissig; in Mexico with Manuel Gutiérrez Nájera.

Despite its early antecedents with González Prada, modernism reached full development in Peru late, at the beginning of the XX century. Among all its representatives, the Lima poet José Santos Chocano (1875-1934) stands out, known as "El Cantor de América", considered one of the most important Spanish-American poets, for his epic poetry with a bombastic tone., who likes rhetoric and the description of landscapes, with great sound and color, being closer to Walt Whitman and romanticism. He also produced lyrical poetry of singular intimacy. All of his poetic creations are worked with refined formalism and he is mostly inspired by the themes, landscapes and people of his country and of America in general. Main works: Iras santas (1895), In the village (1895), Virgin Forest (1896?), The epic of morro (1899), The Song of the Century (1901), Alma América (1906), Fiat Lux (1908), Golden Firsts of the Indies (1934), Gold of the Indies (1940-1941). His life was very romantic and adventurous, linked to that of the Latin American dictators and warlords of his time. During Leguía's Oncenio he held a public controversy with the young writer Edwin Elmore, whom in a fit of rage he murdered by shooting him at point-blank range. After suffering a brief confinement, he left for Chile, where he was assassinated at the hands of a schizophrenic.

Within Peruvian modernism we must also highlight the following poets:

- Leonidas Yerovi (1881-1917), poet and festive playwright, born in Lima. He was killed in front of the local newspaper La Prensa de Lima, at the hands of a Chilean citizen. Despite his premature death, when he had not yet reached the age of 36, he left a remarkable poetic production in which he “mixed lexicon and modernist forms with salt and Creole picardy.” (Tamayo Vargas). It can be said that it was the vulgarizer of modernism, which led him to the popular classes. He is also the author of a very celebrated theatrical work that makes him one of the top figures of the Peruvian dramaturgy of the beginning of the centuryXX..

- Alberto Ureta (1885-1965), poet and professor, author of reflexive and melancholic tone poems. Works: Rumor of souls (1911), Thoughtful pain (1917). He subsequently published: The desert shops (1933), Intimate journal (1933) and Choices of the crazy head (1937). He was also a diplomat divulging Peruvian culture.

- Enrique Bustamante and Ballivián (1883-1937), Limeño poet, one of the finest and most intellectuals in Peru, to say Luis Alberto Sánchez. He was a friend and companion of Abraham Valdelomar, on whom he exerted great influence. Although it was formed under modernism, it nevertheless maintained a poetic personality away from collective commitments. Her poem Antipoems (1926) constitutes a transition to avant-garde.

- Felipe Sassone (1884-1959), Limeño poet, author of a hedonistic, musical and plastic poetry. Main works: The bohemian song, The Aphrodite Foam, Vortex of love. He also dedicated himself to the theatre, and among the many pieces he wrote, are the following: Naughty field, Miss is crazy. and Back to life.

- José Fiansón (1870-1952), a Lithuanian poet, who, to say of the critic Manuel Beltroy, was the most advanced exponent of modernism in Peru. Her poem Foederis Arca is considered one of the best, but the best, of Peruvian modernism. In his last years he settled in Chosica, which he sang in egological verses. His fruitful work is scattered.

An important branch of Peruvian modernism was the so-called Generation of the 900s, also known as the “arielista” generation (so called because it was inspired by the ideas of the Uruguayan writer Enrique Rodó, the author of Ariel, who advocated the Europeanization of Latin America and the formation of intellectual elites to take charge of its direction). Its members handled an elegant prose and delved particularly into the roots of national history, with tendencies towards idealism (Tamayo Vargas). Its main representatives were:

- José de la Riva Agüero y Osma

- Francisco García Calderón Rey

- Ventura García Calderón

- Víctor Andrés Belaúnde

- José Gálvez Barrenechea

In this environment imbued with modernism, an insular figure emerged: José María Eguren (1872-1942), a poet from Lima who paved the way for innovation in Peruvian poetry with his books La Song of the Figures (1916) and Symbolic (1911), close to symbolism and which reflected his inner world through dreamlike images, with which he reacted against modernist rhetoric and formalism.

Avant-garde

Until 1920, modernism was the dominant trend in short stories and poetry, but since 1915 the literary avant-garde timidly made its entry into the national muse. César Vallejo, with his highly innovative works in language focused on anguish and the human condition, belongs to this period, in which the poets Alberto Hidalgo, Alberto Guillén, Xavier Abril, Carlos Oquendo de Amat, Luis Valle Goicochea also appeared., Martín Adán, Magda Portal and the surrealists César Moro and Emilio Adolfo Westphalen.

The most important writer of the moment is Abraham Valdelomar, who in his brief life cultivated short stories, novels, theater, poetry, journalism and essays. Above all, his stories stand out, which tenderly narrate stories of provincial cities and, to a lesser extent, of Lima or cosmopolitan ones. In 1916 he founded the magazine Colónida that brought together several young writers and that, despite its brief existence (only four issues were published), paved the way for the entry of new movements as the avant-garde in Peruvian literature.

Other authors, who along with Valdelomar inaugurated the short story in Peru were Clemente Palma, who wrote decadent, psychological and horror stories, influenced by Russian realism and by Edgar Allan Poe; and Ventura García Calderón, who mostly wrote exotic tales about Peru. There are also Manuel Beingolea, Manuel Moncloa y Covarrubias, Cloamón, and Fausto Gastañeta.

In the theater, with few works of value in this period, there are the comedies of the festive poet Leonidas Yerovi and, later, the works of social denunciation and political aspect of César Vallejo, which spent a long time before being published or represented. Already in the 1940s, the late influence of modernism and poetic theater was reflected in the works of Juan Ríos, who have been criticized for their excessive poetic rhetoric, generally set in ancient times or in legends and who seek to be a general reference. of man.

Indigenism

In Peru, the main theme of indigenous literature was the Indian, whose predominance in literature began in the 1920s and 1930s, first with the stories of Enrique López Albújar and later with the novels of Ciro Alegría: The Golden Serpent (1935), Hungry Dogs (1939) and The World Is Wide and Alien (1941). Thus began the interesting controversy on indigenismo and indianismo, that is, on the question of not being the Indians themselves who write about their problems. This literary current reached its maximum expression in the work of José María Arguedas, author of Agua, Yawar Fiesta, Diamantes y pedernales, The deep rivers, The Sixth, The agony of Rasu Ñiti, All the bloods and The fox above and the fox below, and who, due to his childhood contact with indigenous people, was able to assimilate their conception of the world and experiences as his own.

Generation of 50

The modernization of the Peruvian narrative begins with the Generation of 50, politically framed with the coup of General Manuel A. Odría in 1948 and the 1950 elections in which he elected himself president. During the previous decade, a migratory movement from the countryside to the city (preferably to the capital) had begun, which during the 1950s grew to its maximum potential and resulted in the formation of neighborhoods and young towns, the appearance of marginalized and socially displaced subjects. The literature produced in this period was notably influenced by the European avant-gardes; in particular, the so-called Anglo-Saxon modernism of Joyce and in the American environment the novelistic work of Faulkner and the Lost Generation. The fantastic literature of Borges and Kafka also had a notable influence. To this generation belong Julio Ramón Ribeyro, Carlos Eduardo Zavaleta, Eleodoro Vargas Vicuña, Mario Vargas Llosa, among others.

The Generation of the 50s is a moment in which the narrative is strongly linked to the theme of urban development, the experience of Andean migration to Lima (a drastic increase in the population from the end of the decade of 40). Closely related to Italian neorealist cinema, it portrays the changing city, the appearance of marginal and problematic characters. Among the most representative narrators, Ribeyro stands out with Los gallinazos sin plumas (1955); Enrique Congrains with the novels Lima, zero hour (1954) and Not one, but many deaths (1957); Luis Loayza, whose work is brief and little known; and Vargas Llosa, who at the end of the 50s began to publish his stories, although his magisterial novels appeared from the 1960s.

Along with the narrators, a group of poets arose, including Alejandro Romualdo, Washington Delgado, Carlos Germán Belli, Francisco Bendezú, Juan Gonzalo Rose, Pablo Guevara. These poets began to publish their work from the late 1940s, such is the case of Romualdo, followed by Rose, Delgado, Bendezú, Belli. Guevara. Moreover, this group was united not only by personal relationships, but also by ideology, Marxism and existentialism. The poems they wrote adopted, from a general vision, a protest tone and social commitment. For this reason, the poem A otra cosa by Romualdo is recognized in the poetic art of the generation of the fifties.

This generation vindicated César Vallejo as an aesthetic paradigm and assumed the thought of José Carlos Mariátegui as an intellectual guide. The poets Javier Sologuren, Sebastián Salazar Bondy, Jorge Eduardo Eielson, Antenor Samaniego, Blanca Varela, were known as the neo-avant-garde group, which began to publish at the end of the 1930s (such is the case of Sologuren, then would come the poems of Salazar Bondy, Samaniego, Eielson, Varela). They had personal relationships in the magazine Mar del Sur, directed by Aurelio Miró Quesada, clearly conservative; and they appointed Emilio Adolfo Westphalen as poetic guide. To this historical-literary situation, we should add the group of so-called People's Poets, linked to the Aprista party founded by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre, made up of Gustavo Valcárcel, Manuel Scorza, Mario Florián, Luis Carnero Checa, Guillermo Carnero Hoke, Ignacio Campos, Ricardo Tello, Julio Garrido Malaver, who claimed Vallejo as a poetic paradigm.

During that decade and the next, the theater underwent a period of renewal, initially with pieces by Salazar Bondy (generally comedies with a social content) and later with Juan Rivera Saavedra, with works of strong social denunciation, influenced by expressionism and the theater of the absurd. During these years the influence of Bertolt Brecht will be strongly felt among playwrights.

Generation of '60

The Generation of 60 in poetry had representatives of the caliber of Luis Hernández, Javier Heraud and Antonio Cisneros, Casa de las Américas Award winner. Also worth mentioning are César Calvo, Rodolfo Hinostroza and Marco Martos. It should be noted that Heraud was the true generational paradigm, linked to Marxist doctrine and political militancy, while Hernández and Cisneros were not. As it is easy to notice, contemporaries do not constitute generational movement.

The narrators Oswaldo Reynoso, Miguel Gutiérrez, Eduardo González Viaña, Jorge Díaz Herrera, Alfredo Bryce Echenique and Edgardo Rivera Martínez belong to this generation.

Peruvian narrative and poetry of the late 1960s were not so much generational as ideological: literature was seen as a means, an instrument to create class consciousness. Those were the years of the height of the revolution in Cuba and in Peru the majority of intellectuals yearned for a Marxist revolution that would break the old oligarchic and feudal order. Some writers aspired to a process like the Cuban one (Heraud, for example, died in May 1963 in the Peruvian jungle, as part of a column that intended to launch the guerrilla struggle), while others had their own models. In this period of intense social commitment, the writer has little room for commitment to his own work. At the end of this decade, the Grupo Narración emerged, influenced by Maoism and led by Miguel Gutiérrez and Oswaldo Reynoso, also joining Antonio Galvéz Ronceros and Augusto Higa, who edited a magazine with the same name, although they had thinking of calling it Water, evoking José María Arguedas and the social tensions that the book of that title shows.

Generation of the 70s

The first expressions with their own characteristics, of what would later be called the Generation of the 70s, emerged at the end of the 60s with authors such as Manuel Morales (1943-2007), author of the Peicen Bool (1968) and Poemas de entrecasa (1969); and Abelardo Sánchez León (Poemas y ventanas cerradas, 1969) who experimented with popular colloquialism.

One of the first magazines to welcome the new voices will be Estación Reunida, in which José Rosas Ribeyro, Patrick Rosas, Elqui Burgos, Tulio Mora, Óscar Málaga and others publish. In 1963, the Gleba Literaria rupture movement burst onto the poetic scene in the cloisters of letters of the Federico Villarreal University, being a voice in opposition to the political moment that the country was experiencing, having Jorge O. Vega (1940-2017) as its founder, housing to other insurgent poets such as Manuel Morales, Carlos Bravo E, among others. With the appearance of the Zero Hour movement and its homonymous magazine, in 1970, this generation established a presence on the Peruvian cultural scene. It was founded by Juan Ramírez Ruiz and Jorge Pimentel, students from the Federico Villarreal National University, and its ranks also included Enrique Verástegui, Carmen Ollé, Jorge Nájar, Mario Luna and Feliciano Mejía. The latter would definitely move away from Hora Zero in 1972.

The first writers awarded the important Young Poet of Peru award were José Watanabe (1945-2007), (Family Album) and Antonio Cillóniz (After walking for some time towards the This), who shared it in 1970.

In addition to popular colloquialism as a poetic expression, the Generation of '70 will also be characterized by its break with the Peruvian literary tradition prior to it and its left-wing ideological radicalism, as proof of the aforementioned, is the ratification by generational majority to such literary commitment, in the Congress of Poets held in the city of Jauja in April 1970. Another important expression of this generation is the rise of the magical poets, neo-avant-garde who resumed the Dadaist experiments with César Toro Montalvo, Omar Aramayo, and José Luis Ayala. The poetry of social protest will have an outstanding cultor in Cesareo Martínez. Outside the groups, other voices stand out, such as Vladimir Herrera's.

Starting in 1974, there was a second moment in the Generation of 70 that was expressed in the pages of magazines with very limited circulation such as La Tortuga Ecuestre, Cronopios, Literature, Auki, Tallo de Habas and some others. His poets, in some way, try to take some distance from the characteristic colloquialism of the first stage and give themselves more to the careful cultivation of form. In this second moment, the voices of Mario Montalbetti, Juan Carlos Lázaro, Carlos López Degregori, Luis La Hoz, Enrique Sánchez Hernani, Bernardo Rafael Álvarez, Armando Arteaga, Alfonso Cisneros Cox, Jorge Luis Roncal, Gustavo Armijos, Jorge Espinoza Sanchez.

On the other hand, with the posthumous publication of a handful of poems by María Emilia Cornejo in the magazine Eros, poetry written by women in Peru inaugurates a new language, a new expression of female problem. The aforementioned Carmen Ollé, Sonia Luz Carrillo, Rosina Valcárcel, Rosa Natalia Carbonell, among others, will stand out.

Although the 1970s was a fundamentally poetic generation, it was not without narrators. In the initial years of literary turmoil, under the influence of the important fashions of the counterculture and the hippies, its most visible narrator was Fernando Ampuero, who over time would develop an important and sustained work of short stories, novels, and journalism. With less attention from the media, but with no less important works, the storytellers Óscar Colchado, Cronwell Jara, Maynor Freyre, Zein Zorrilla, Luis Nieto Degregori, and Enrique Rosas Paravicino also belong to this generation.

Collective creation breaks out in theater as opposed to works of authorship. The movement was led by several theatrical groups that emerged in recent years, among which stand out Cuatorablas, headed by Mario Delgado, and Yuyachkani, by Miguel Rubio Zapata, both created in 1971.

It is worth noting the poetic work and perseverance, from the provinces, of Alberto Alarcón, Houdini Guerrero, Emilio Saldarriaga, Segundo Cansino, Carmen Arrese, among others. In Arequipa, the magazines Ómnibus and Macho Cabrío marked an era. The group of poets linked to the San Agustín University (Oswaldo Chanove, Alonso Ruiz Rosas, among others) was very active.

1980s and 1990s

With the 1980s comes disenchantment, pessimism: the arrival of a communist revolution is no longer a utopia, but it is no longer expected, it is almost a threat. It is the time of perestroika and the last years of the cold war. In addition, the economic crisis, terrorist violence and the deterioration of living conditions in a chaotic and overcrowded Lima contributed to collective discouragement. In narrative, the first storybooks by Alfredo Pita appear, Y de pronto anochece; by Guillermo Niño de Guzmán, Midnight Horses; and Alonso Cueto, The battles of the past, authors whose literary work will be fully developed in later years.

In poetry, marginal movements arose, deepening the rebellious side of the previous decade, such as the Kloaka, led by Roger Santiváñez and Domingo de Ramos. Founded towards the end of 1982 and disappeared in 1984, it edited an anthology: La última cena (1987). In contrast to the collective proposals of neo-avant-garde spirit (in general, of rupture with the political and aesthetic system), notable individuals also arise, linked in their origins with these, but who quickly transition to a serene poetry, with balanced rhythms and that it nourishes strongly codified artistic traditions. The most notable case is that of José Watanabe, a poet from the 1970s whose best work corresponds to this decade and who will be revalued in the new century. Other notable poets within this traditional approach to individualization were Eduardo Chirinos, Raúl Mendizábal, José Antonio Mazzotti and Magdalena Chocano. In the same decade, the first and diversified women's poetry movements also emerged. There is the feminist line, within which Carmen Ollé, Giovanna Pollarollo and Rocío Silva Santisteban stand out, and another more lyrical one, where Rossella Di Paolo stands out, as well as the ironic intimacy of Milka Rabasa. It is also worth mentioning Patricia Alba, Mary Soto, Mariela Dreyfus and Dalmacia Ruiz-Rosas.

In the 1990s, an individualist trend appeared that delved into aesthetic intention. In poetry where several poetic groups or collectives arise. In the narrative, the formula that prevails is the so-called young-urban-marginal. In this field, in addition to Jaime Bayly, who has a preference for the sensationalist, Óscar Malca stands out with At the end of the street (1993), Sergio Galarza with Matacabros (1996), Rilo with Contraeltrafico (1997), authors who cultivate dirty realism.

On the other hand, there are some writers who cultivate aestheticism and whose work escapes the molds of their generation, among them Iván Thays, with The photographs of Francés Farmer, and Patricia De Souza, with When night comes. In poetry, Montserrat Álvarez stands out with Dark Zone (1991), Xavier Echarri with Las quebradas experiencias (1993), Palm Sunday with Ósmosis (1996), Doris Moromisato, Odi González, Ana Varela, Rodrigo Quijano, Jorge Frisancho, Ericka Ghersi with "Zenobia and the Old Man" (1994), Rafael Espinosa, among others anthologized in the controversial anthology Peruvian Poetry siglo XX (2000) by Ricardo González Vigil (Catholic University).

Around 2000, as Vigil points out in volume 14, Literature, of the Thematic Encyclopedia of Peru of El Comercio, Lorenzo Helguero shows an important poetic work, Miguel Ildefonso, Selenco Vega, José Carlos Yrigoyen, Alberto Valdivia Baselli, among others. In the dramatic field, Enrique Mávila and Mariana de Althaus stand out, who have been characterized by the assimilation of different contemporary theatrical trends. And in the field of short narrative, the work Fábulas y antifábulas, by César Silva Santisteban, is singular.

Simultaneously, two writers from the Narration group reached their maturity during this decade: Oswaldo Reynoso and Miguel Gutiérrez, who returned to Peru after a long stay in communist China, which disappointed them of their adventures youth policies. Reynoso, author of the memorable book of short stories The Innocents, successively published the novel In Search of Aladdin and the novel The Immortal Eunuchs, works of prose musical in which the ideal of social class struggle is discarded in search of a utopia of youthful beauty that is, nevertheless, justifiable to the humble. Gutiérrez, for his part, surprises readers with a novel of more than a thousand pages, La violencia del tiempo, a family saga of the Villar family, which begins with the first Villar, a deserter from the Spanish army who fought against the patriots in the war of independence, and ends with Martín Villar, the novel's narrator, who in the sixties has chosen to be a rural teacher, after studying at the oligarchic Catholic University. A historical novel of growth, an essay on social criticism and historical interpretation, La violencia del tiempo shows the influence of the great Latin American narrators of the century XX (Jorge Luis Borges, Juan Rulfo, Gabriel García Márquez and Mario Vargas Llosa), as well as the masters of the century novel XIX, especially Balzac, whose intense and grim family chronicle, The Human Comedy, evokes with singular mastery.

21st century

At the turn of the century and in the early years of the decade, several of the most important international awards were given to Peruvian writers, some of them unknown abroad until then. From this, the possibility of an international relaunch of our letters is raised, which had diminished in foreign presence during the last two decades of the century XX. In fact, this rise in Peruvian literature began in 1999, when the novel The absent hunter, by Alfredo Pita, won the Las dos orillas prize, awarded by the Salon del Ibero-American Book of Gijón (Spain). Pita's book was immediately translated and published in five European countries. In 2001 Gustavo Rodríguez published his first novel, La furia de Aquiles, with which he began a literary work that has earned him progressive consolidation and being a finalist in international awards such as El Herralde and El Planeta. -Casamerica.

A year later, in 2002, an already consecrated narrator, Alfredo Bryce Echenique, obtained the Planet with El huerto de mi amada, awarded by the publishing house of the same name, the most powerful in Spain and one of the the largest in the world. The following year, Pudor, Santiago Roncagliolo's second novel, was among the four finalists in the Herralde and was later published by Alfaguara in 2004 with an audacious marketing operation. In 2005, Jaime Bayly, criticized by his detractors for using narrative as a complement to his television celebrity, is the only finalist for Planet. That same year Alonso Cueto won the Herralde with La hora azul ; the following year Roncagliolo, with Abril rojo, won the novel prize awarded by his publishing house and the following year the novel El susurro de la mujer ballena, by Cueto, was a finalist in the first edition of the Planeta-Casa de América Award. Iván Thays, who had already been a finalist for the Rómulo Gallegos 2001, is among the finalists for the Herralde 2008 with A place called Oreja de Perro. Finally, the Nobel Prize for Literature was awarded to Vargas Llosa in 2010. In this sequence of events, the incorporation of numerous Peruvian literature into the flow of circulation of Spanish letters in the globalized world can certainly be traced.

Although the phenomenon gave a new relative visibility in the Spanish-speaking world to national letters, it is also true that the internationalization of these writers and their awarding meant the rise of a new Peruvian literature limited to certain recognizable patterns that favored the global publishing industry. From this perspective, the literary transnationals, which in the early years of the XXI century established their subsidiaries in Lima, demanded that the writers better connected with the publishing market a greater professionalization that would satisfy the standards of basic pre-established writing formats, to the detriment of an original production. In this new professional profile, it is possible to understand the novels by Jeremías Gamboa, Contarlo todo, and Renato Cisneros, The distance that separates us. However, within a literary scene encouraged by the growth of the Lima book market, transnationals also promoted, in a complementary way, artistically innovative and even experimental proposals aimed at audiences less fascinated by the successes of best-sellers and related to discussion. intellectual.

In parallel to the international resurgence and the recognition of authors such as those mentioned, in recent years Peru has also developed, as part of the dynamics of a multicultural country, a literary process led by authors who place their work in the boundaries of Andean culture, rescuing it as an artistic form product of the specificity of the Peruvian nation and its drama. The writers of this tendency claim, on the one hand, the inheritance of the work of José María Arguedas and, on the other, they denounce the discrimination on the part of critics and media of "Creole" orientation, or culturally more related to the globalized economic system, which governs the administration of the so-called "cultural assets". The dispute between "Andeans" y criollos became clear as a result of a series of aggressive articles published by both sides after a first mutual disqualification when they met at a congress of Peruvian writers in Madrid. As a consequence of the public dispute, a new generation of provincial writers gained visibility that continues, in a contemporary and even postmodern key, the indigenous (and regionalist) narrative of the 40s (ties with Alegría and Arguedas in particular emerge), with the work by Manuel Scorza and with the regionalist and rupture narrative of the 70s (Eleodoro Vargas Vicuña, Carlos Eduardo Zavaleta, Edgardo Rivera Martínez, the Narración group). A reconstruction of the past is privileged through a process of fictionalization of history, taking up a point exploited by the new Spanish-American narrative and the boom. Thus, if they are not the first, they are the ones that delve deeper into the literary treatment of the process of the internal war (1980-1993). The insertion in the national literary market of these writers is, moreover, different from the narrators of the capital, since the diffusion of their works is carried out mainly in the provinces and through alternative forms (regional fairs, folkloric concerts, newspapers or limited-run magazines).).

It is also important to point out the significant growth experienced by the Peruvian publishing market in the first decade of the XXI century, due to the reduction of costs that the introduction of digital technology has meant in the publishing field, the validity of the Book Law and the promotion of the Reading Plan of the Ministry of Education. On the one hand, various independent publishers have appeared, such as Estruendomudo, Matalamanga, Atalaya Editores, Sarita Cartonera, Bizarro, Borrador Editores, [sic] libros, Mundo Ajeno, Tranvías, Lustra, Mesa Redonda, Casatomada, Editorial Arkabas, Gaviota Azul Editores, among others. These houses prompted the creation of the Peruvian Publishers Alliance, an independent union affiliated with a global movement in defense of bibliodiversity. Among the new publishers, Estruendomudo, in particular, is responsible for the appearance and dissemination of new narrators and poets praised by critics. On the other hand, one of the largest groups in the Spanish-speaking world, Planeta, inaugurated its subsidiary in Peru in 2006, giving further impetus to a market in which two other large international groups were already operating: Santillana (Spain) and Norma. (Colombia); unfortunately, the latter abandoned fiction. This small editorial boom has allowed a large number of new writers to publish their first works during this decade, especially young writers born in the 70's.

In 2017, the Ministry of Culture of Peru resumed the call for the National Award with the aim of both recognizing and positioning the works of national authors in the market, as well as stimulating the work of the country's publishing industry.

Nobel laureates

| Nobel Prizes | |||

| Writer | Year | Image | Date |

| Mario Vargas Llosa | 2010 |  | "by his cartography of the structures of power and his dying images of the individual's resistance, rebellion and defeat." |

Contenido relacionado

Eduardo Marquina

The Truman Show

Jose Enrique Rodo