Pergamon altar

The Pergamum Altar is a religious monument from the Hellenistic era originally built on the acropolis of Pergamum, early in the reign of Eumenes II (197-159 BC). Its monumental friezes represent a Gigantomachy or fight between gods and giants on the outside, and on the inside the story of Telephus, the legendary founder of the city. These friezes are considered one of the masterpieces of ancient Greek sculpture and they represent the culmination of the so-called Hellenistic Baroque.

The typology of the building was not that of a temple, but rather an external altar that was probably related to a nearby temple dedicated to Athena and therefore the altar worshiped this divinity, although another possibility is that Zeus and Athena were equally worshiped in this place.

The altar was a rectangular U-shaped building that rose on a large podium, which was accessed through a monumental staircase. It had two levels: the lower one, made up of a continuous wall where the frieze of the Gigantomachy was represented, and the upper one, made up of a double row of Ionic order columns. The staircase was closed by two lateral bodies that advanced towards the front of the building. When entering the interior, another double Ionic colonnade was crossed until reaching a closed courtyard where the sacrificial altar was located. The original dimensions of the altar were 69 meters long, 77 meters wide and 9.70 meters high. The part that is preserved measures 36.44 meters wide by 34.30 meters deep, and the front staircase is 20 meters wide.

Discovered in 1871 by German architect Carl Humann, the altar was transported to and rebuilt in Berlin in 1886, under an 1879 agreement between Germany and the Ottoman Empire. Since then, the large frieze of sculptures has been on display in the Pergamon Museum, one of the State Museums (Staatliche Museen) on the city's Museum Island. For some decades the Turkish state has been demanding its restitution without success.

On September 30, 2014, almost all of its rooms were closed for renovation. It is estimated that the refurbishment work will take approximately five years. It is expected that the main rooms will be enabled in 2019, including the one with the altar. It is estimated that the Pergamon Museum will again be fully accessible to visitors in 2025/26.

History

Pergamum

Pergamum was the capital of the Attalids and one of the most important cities of the Hellenistic kingdoms that developed after the death of Alexander the Great. The kings that succeeded him ordered the construction of notable monuments as a symbol of their power, inspired by the great cities of classical times.

However, contrary to the Greek cities, Pergamum was located in the center of a great kingdom and therefore it was not only a unit in itself, but the place where the economic and political power of the whole was concentrated. a region, which explains its urbanism, less functional but more monumental. This race towards a grandiose architecture is part of a context of political and intellectual rivalry between the great Hellenistic cities, mainly with the capital of the Ptolemies, Alexandria. Thus, the altar could have been considered as a reflection of the imposing philological and mythological culture maintained by the priests and lawyers of the Attalid court.

Built at an altitude of 335 meters, the city is the superposition of three villas, linked to each other by means of stairs with belvederes and raised terraces on two-story porticoes. In the upper city the administrative and civic buildings were located: the agora, the palace, the arsenal, the library, the theater, the temples of Dionysus and Athena Polias and the great altar. In the middle zone there was a magnificent gymnasium, the temples of Demeter and Hera Basileia and the Prytanium. The lower town was the commercial core.

The city, in addition to being an architectural achievement, was located in the center of a rich region dedicated to wheat, vines and livestock. The industry was diversified, its main products being perfumes, fine cloth and parchments. Its library rivaled that of Alexandria, with some 200,000 volumes, and the royal palace housed a large collection of sculpture. In addition, it was famous for its oratory school and its sculpture workshops, and its Dionysian artists made the city the main center of dramatic art.

Date of construction of the altar

The dating of the altar is controversial. It is known to have been built during the II century BC. C.. since one of the fragments of a dedication has the inscription ΒΑΣΙΛΙΣΣ (Α), that is, "queen". The word almost certainly refers to Apollonide, wife of Attalus I and mother of Eumenes II and Attalus II. Since no common epitaph is known to Attalus I and Apollonide, it is assumed that she was named queen mother. In fact, Eumenes II and Attalo II are habitually called the "sons of King Attalus and Queen Apollonide". The great altar could then be dated to a date later than 197 BC. C., the year of the death of Atalo I. Based on several ceramic pieces found in the foundation, experts have estimated that the construction would have been carried out around 168 or 166 BC. C., date of the end of the war against the Galatians. However, it is generally accepted that the decision to start the project dates back to the beginning of the reign of Eumenes II, after the peace of Apamea in 188 BC. C., period in which the kingdom of Pergamum was at its peak. It is unknown how long the construction work lasted. It is probable that the Gigantomachy was carried out in the first place, if one takes into account the perfect finish of the work. As regards the Telephus frieze, its incompleteness would undoubtedly be explained by the end of the Attalid dynasty, in 133 BC. c.

Already in the time of Atalo I began the remodeling of the acropolis of Pergamum. Over time, a temple of Dionysus, a theater dedicated in his name, a heroon, an upper agora for the city, and the great altar now known as the Pergamon altar. Several palaces and a library were also built in the sanctuary of Athena.

Roman times

In about the II century, the Roman writer Lucius Ampelius wrote in his work Liber Memorialis, in chapter VIII (Miracula Mundi) a chronicle of the altar: «In Pergamum there is a great marble altar, 40 feet (12 meters) high, with colossal sculptures. It also shows a Gigantomachy".

Aside from a comment by Pausanias, who compares the practice of sacrifice at Olympia to that at Pergamum, this is the only written reference to the altar in all of antiquity. This fact is surprising since classical writers wrote a lot about works of art and Ampelio, after all, considered the altar one of the wonders of the world. The absence of written sources in antiquity about the altar has given rise to numerous interpretations. One possibility is that the Romans did not consider this Hellenistic altar of great importance, since it did not date from classical Greece, especially Attic art. Only this era and the subsequent evocation of its associated values were considered significant and worth mentioning. This hypothesis was espoused by German researchers in the early 18th century, particularly after the disclosure of the works by Johann Joachim Winckelmann. The only graphic representations of the altar appear on coins from the Roman Empire, which show the altar in a stylized form.

Throughout the 20th century, the perception and interpretation of antiquities from periods other than the «classical» one have been re-studied. From that moment, it is unquestionable that the great altar of Pergamum is one of the most significant works, if not the culmination, of Hellenistic art. Currently, an uninformed and low level opinion about the altar would be unusual. The Laocoon and his sons, located in the Vatican Museums, is one of the few sculptures that are considered today as great examples of the art of antiquity. Declared already in Roman times as "a masterpiece that surpasses all other paintings and sculptures", it could have been based on an original also from a work in Pergamum. The Vatican sculptural group was created at about the same time as the altar.It is significant that the goddess Athena's opponent at the side of the giants, Alcyoneus, bears a strong resemblance to Laocoon in his pose and appearance.

From Ancient Times to the 19th century

The altar lost its function in late antiquity, when Christianity replaced and suppressed polytheistic religions. In the VII century the acropolis of Pergamon was fortified as a defense against the Arabs. During the process, the Pergamon altar among other buildings was partially destroyed to be reused as building material. However, the city was defeated in 716 by the Arabs, who temporarily occupied it before abandoning it as unimportant. It was refounded in the 12th century, and in the XIII fell into the hands of the Turks.

In the 13th century, Theodore Laskaris, future emperor of Nicaea, visited the ruins of Pergamum, although he made no mention of it. some of the altar in his letters. Between 1431 and 1444, the Italian humanist Ciríaco de Ancona also traveled to the city and described it in his commentarii or travel diary. In 1625 William Petty, chaplain to Thomas Howard, 21st Earl of Arundel, a collector and art patron, traveled through Turkey and visited Pergamon, taking two altar panels back to England with him. Later, in 1811, Charles Robert Cockerell only observed the fragments of a temple, which the inhabitants of the neighboring villages had transformed into tombstones.

Archaeological discovery

The German architect Carl Humann had already worked in Samos, where he had participated in the excavations of the Hereo begun in 1861, when he first visited Pergamum in 1864. He entered the service of his brother Franz, who had obtained the right to build some roads in the western part of the Ottoman Empire. Thus, he settled in Pergamum in 1868 and became the head of a team made up of 2,000 workers, 1,000 oxen and 500 camels, horses and mules.

In 1871, when the well-known German archaeologist Ernst Curtius visited his excavation, he had already unearthed a certain number of sculptures that seemed to constitute a series. Curtius encouraged him to send them to Berlin, and that same year he sent three fragments of what he defined as a "battle between men, horses and wild animals" The pieces went unnoticed for five years at the & # 34; Altes Museum & # 3. 4; (old museum).

In December 1871, a marble panel with the sculpted figure of a giant was found on a Byzantine wall on the acropolis of Pergamum. Humann recognized that he was looking at a masterpiece, although he believed that the frieze came from the nearby temple of Athena. The mural was immediately sent to Berlin. In 1877 Alexander Conze, the new director of the Berlin Museum's sculpture collection, found in the work of Lucio Ampelio a reference to an altar of the giants, which allowed a more precise identification. Conze focused his interest on the shards and hastily wrote to Humann to start the excavation, asking to be his representative on site to find the other parts of the altar.

In August 1878, the German government obtained a firman from the Ottomans that allowed it to inspect the acropolis of Pergamum. A first agreement was signed, where one third of the findings would go to the owner of the land, another third to the discoverer and another third to the Ottoman State. The ambassador was initially able to obtain the first two thirds for Berlin. Starting in 1879 and following a new agreement between Germany and the Ottoman Empire, the fragments of the altar were transported to Berlin. The Ottoman government initially wanted the findings to be shared, but German influence, the political weakness of the Ottoman Empire following its defeat against Russia, Bismarck's mediating role during the Congress of Berlin, and a payment of 20,000 marks of gold allowed Germany to recover all the pieces.

The excavations were carried out in three campaigns: 1878-1879, 1880-1881 and 1883-1886. The first campaign began on September 9, 1878 with the opening of a trench between the Byzantine wall and the Attalid wall, south of the acropolis. The elements of the altar had been used for the construction of the wall, in such a way that the relief was towards the interior. By September 24, seventeen panels had already been discovered. By the end of December, thirty-nine panels of the Gigantomachy and four of the Telephus frieze had been found, close to 800 fragments, a dozen statues and thirty inscriptions. For this, 1,800 cubic meters of earth were unearthed. By 1880, ninety-seven sheets had been excavated. Surveys in the acropolis revealed the base of the altar. Before 1901 and the construction of the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, ninety-four frieze panels and 2,000 fragments had been found. It took half a day of work and twenty workers to be able to dismantle a panel from the Acropolis. Humann easily managed to get an idea of the plan of the altar thanks to the position of the frieze, although he had to wait a long time for the clearing to find the first architectural vestige. The work to remove the altar from the Byzantine wall lasted 1,300 days. Humann even had a road built to facilitate the exit of the marbles, which he later had destroyed so that no one else could use it. A new jetty was built to ship the pieces. To prevent the Ottomans from seeing what had actually been discovered, Humann left the Byzantine cement on the frieze and had it transported upside down. He even managed to buy the fragments that had been previously discovered by others and found in Constantinople.

20th century

Initially, there was no suitable place where the altar panels could be displayed and they were temporarily housed in the overcrowded Altes Museum, where the Telephus frieze in particular could not be properly displayed. For this reason, the construction of a new museum was proposed. The first Pergamon Museum was built between 1897 and 1899 by Fritz Wolff and opened its doors in 1901, with the presentation of a bust of Carl Humann by Adolf Brütt. This building was used until 1908, although it was considered only as a temporary solution and was therefore called the "temporary building".

Four archaeological museums were projected, in one of which the altar of Pergamon would be installed. However, the first building had to be demolished due to foundation problems. In addition, it was considered that the finds that could not be presented in the other three would be housed inside, and therefore from the beginning the space was too small for the altar.

Thus, in 1910 construction work began on a new museum in Pergamon, designed by Alfred Messel. It was inaugurated in 1930, due to delays caused by World War I, the November Revolution, and Hyperinflation in the Weimar Republic in 1818-19. The new building presented the altar in a similar way to the one that can be seen today. A partial reconstruction of the central gallery allowed the installation of the fragments of the frieze on the perimeter walls. The stairs lead to the Telephus frieze, just as it was in the original construction, although only a part of it is on display. The reason why the entire altar was not rebuilt when the new museum was built and the frieze was installed is unknown. When the exhibition was devised, Theodor Wiegand, the museum's director at the time, followed the ideas of Wilhelm von Bode, who had in mind a large "German Museum" in the style of the British Museum in London. But obviously there was no global approach, and despite the fact that it was planned to build a large museum of architecture, which would show examples of all the Mediterranean culture and the ancient Middle East, the arrangement of the altar in the building had to be reduced. Until the end of World War II, only the eastern part of the museum with the three large galleries was called the "Pergamon Museum".

The altar has always remained inside the museum, except for the period between 1945 and 1959. In 1939, its doors were closed due to World War II. The altar was hidden at first in the cellars of the Reichsbank, and later in a bomb shelter in Tiergarten. In 1945, Soviet troops seized the monument, dismantled it, and took it to Russia as spoils of war. It was exhibited in the Hermitage museum in Leningrad, now Saint Petersburg. The Pergamon museum was in the Soviet-occupied zone, and it was not until 1958 that most of its objects were returned to East Germany, including the Pergamon altar. In 1990, nine heads from the Telephus frieze, which had to be moved to the west of Berlin due to the war, they were returned to the museum.

The monument has suffered various problems due to previous incorrect restorations. The staples and dowels that connected the fragments and anchored the frieze and sculptures to the wall were made of iron. When these began to rust, they increased in volume, with the danger of breaking the marble from the inside. Therefore, since 1990 an emergency intervention was imperative. From 1994 to 1996 the Télefo frieze was intervened, including some parts that were inaccessible in the 1980s. Later the Gigantomachy was restored under the direction of Silvano Bertolin. First the west frieze was intervened, then the pieces on the north and south sides, and finally the east frieze. The operation cost more than three million euros. On June 10, 2004, the frieze, fully restored, was presented to the public again.

In 1998 and later in 2001, the Turkish Minister of Culture, Istemihan Talay, requested the return of the altar and other objects to his country. However, this request was not official and would not be applicable under current standards. In general, the Berlin State Museums, as well as other museums in Europe and the United States, rule out the possible return of objects from their collections. Currently, most of the foundation and various remains of the altar walls remain in their original location. Likewise, several pieces of the frieze of small dimensions, which were found later, are preserved in Turkey.

Description

The building

In classical times, temples dedicated to the great gods or the local gods of each city were erected. In front of them were placed the altars for sacrifices, which were constructions of little importance. Later, during the Hellenistic period, large monumental altars were built, dedicated to a deity, usually Zeus.

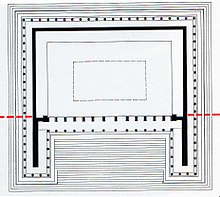

The Pergamon altar was a colossal construction raised on a podium, respecting the original vision. It was built on the second terrace of the city's acropolis and followed the traditional pattern of buildings in eastern Greece. From a large rectangular central body, two lateral wings protruded from the sides, framing a monumental staircase that in turn led to a central courtyard with an exterior perimeter colonnade.

The building consisted of two heights. In the lower part was the great frieze of the sculptures, which was not part of the entablature but of the podium of the temple. At the top there was an Ionic order colonnade divided into three bodies, a central one at the bottom and two lateral ones. The central colonnade gave its back to the quadrangular central patio, which was the space reserved for sacrifices. In this place, incense was burned and libations were made in honor of the gods. Following the Ionian tradition, the altar table was placed on a large base with steps that in this case constituted a unit with the architectural ensemble.

The sculptural decoration made with medio-reliefs was developed on the podium or basement. In this exterior part of the building a Gigantomachy was represented, that is, the mythological combat between the giants, sons of Gaia, and the Olympic gods. The frieze was 2.30 meters high and 113 meters long. It was topped by a very prominent cornice, with denticles. The scenes were not separate, but rather a continuous frieze that depicted a moment in the battle. The panels on the interior walls of the courtyard, 1.10 meters high and 90 meters long, depicted the story of Telephus, son of Heracles and legendary founder of Pergamum. Finally, on the roof of the colonnades, there were some acroteras with the images of gods, horses, griffins, centaurs and lions.

A recent reconstruction suggests that the intercolumnium would have been occupied by statues. Thus, the group called little Gauls or little Galatians could have been located on the edge of the altar. Despite this sculptural profusion, the work remained incomplete, since some decorations of the upper columns and the Telephus frieze are unfinished.

The remains of the dedicated inscription on the architrave do not reveal the divinity to which the altar was consecrated, so it is given the conventional name of "Great Altar". The most feasible hypotheses point to Zeus, Athena (protector of Pergamum), both at the same time or even the twelve gods of Olympus. As for literature, it does not contribute much to archaeology, since despite the exceptional character of the building, only the writer of the III century a. C. Lucio Ampelio mentions the altar in his work On the other hand, his testimony does not contribute anything new in regards to the knowledge of the monument.

The altar of Hera in Samos, the one of Zeus also in Pergamon and the one of Asclepios in Cos, all of them belonging to the IV a. C. In all three cases a similar formal distribution is followed, in which the altar is surrounded by a wall and elevated on a podium, it has a horseshoe shape and in the examples of Pergamum and Cos it is flanked by two lateral colonnades. The access to the altar was also produced through a staircase. The first two buildings are known from Pausanias' account in his work Description of Greece, and the second is also known from a bronze coin dating from the II a. C. These three altars have smaller dimensions than the great altar of Pergamon, being the one of Samos the only one comparable in size.

Function of the altar

Contrary to popular belief, the Pergamon altar was not a temple, but probably the altar of a temple, although altars were usually located outside facing them. It is believed that the temple of Athena, located on the terrace of the upper acropolis, could have been her cult reference point, and that the altar would have served only as a place of sacrifice. This theory is reinforced by the discovery of various statue bases and consecration inscriptions around the altar, whose donors mention Athena. Another possibility is that Athena and Zeus were honored together. It could also happen that the altar had an independent function. Unlike a temple, which always had an altar, an altar did not necessarily have to have a temple. The altars could be relatively small and be located in houses or, less frequently, have enormous dimensions as in the case of Pergamon. The few remains of inscriptions do not provide enough information to determine the identity of the god to which it was dedicated. the altar.

So far, none of these theories is fully confirmed. This situation led the former director of the Pergamum excavations to the following conclusion:

No research is indisputable in relation to the most famous masterpiece of Pergam, neither the builder, nor the date, nor the occasion, nor the purpose of the constructionWolfgang Radt

Equally uncertain is the nature of the sacrifices that were made at the site. Judging from the remains of the relatively small fire altar installed inside a huge building, one can only conclude that it was in the shape of a horseshoe. In appearance it was an altar with two protruding wings on the sides and one or several steps in front. The thighs of sacrificed animals were possibly cremated here. But it is also likely that the altar served only for libations, the offering of sacrifices in the form of incense, wine, and fruit. It is possible that only priests, members of the royal family and distinguished foreign guests were allowed access to the fire altar.

Proportions and the golden ratio

An investigation carried out by Patrice Foutakis has tried to answer the question of whether the ancient Greeks used the golden ratio in their architecture, an irrational number equivalent to 1.61803...etc. With this objective, the dimensions of fifteen temples, eighteen monumental tombs, eight sarcophagi and fifty-eight funerary stelae, belonging to the V a. C. to the II century B.C. The result of this investigation indicated that the number of gold was not used in Greek architecture of the 5th century a. C. and that hardly appears in the following six centuries.

Four exceptional cases of application of the golden number were identified in a tower, a tomb, a funerary stela and in the great altar of Pergamon. On the front sides of the frieze, the proportions are 2.25 meters high by 5.17 meters wide, that is, a ratio of 1/2.25, the same ratio as in the Parthenon. The city of Pergamum maintained close ties with Athens, its kings admired Attic art and sent offerings to the Parthenon, while both cities had the same patron goddess, Athena. In addition, the temple of Athena Polias Nikephoros in Pergamon, located a few meters from the altar, housed a copy of the chryselephantine statue of Athena, made by Phidias for the Parthenon. The two constructions that close the monumental stairway of the altar are presented as two Ionic temples. The proportions of each of them is as follows: the width of the stylobate is 4.722 meters for a length of the stylobate of 7.66 meters, that is, a ratio of 1/1.62. The height with the entablature is 2.93 meters for a width of the stylobate of 4.722 meters, that is, a ratio of 1/1.61. When the visitor climbs the stairs and passes through the portikon, they enter a courtyard that was originally delimited by a colonnade 13.50 meters wide and 21.60 meters long, that is, a ratio of 1 /1.60.

In other words, according to Foutakis, the architect who made this altar wanted the viewer, standing in front of the monument, to be able to see two Ionic temples provided with the golden number, and after having climbed the stairs, they located in a courtyard that also followed the golden ratio. The political and cultural antagonism between Pergamum and Alexandria, the city where Euclid developed his geometric proportion of extreme and mean ratio, could have been the origin of its rapid spread in Pergamum, a town already very open to novelties in science, sculpture, architecture and politics.

Gigantomachy

Like the Centauromachy (or combat between centaurs and tombstones) and the Amazonomachy, the Gigantomachy is a very popular iconographic theme in Ancient Greece, which represents the victory of order over chaos. In the context of Pergamon, where the triumph of Zeus and Athena against their enemies the giants is represented, this is an obvious allusion to the victory of the city against the Galatians. The altar frieze is made up of 120 panels of 2.30 meters high, with a variable width between 70 centimeters and 1 meter, and a thickness of 50 centimeters. This thickness allowed the relief figures to have great depth. Each panel was conceived to represent an important character.

The frieze shows a hundred figures representing the fight of the gods against the giants,each of them designated by name: on the upper cornice there is an inscription with the name of each god, and in smaller characters on the lower base there is another one for the giants. Except for one of them, Mimas, the name of none of the other giants is known. The sculptors must surely have drawn on the scholarship of a court poet.

In accordance with the classical tradition of the frieze, the figures stood out against a dark blue background and occupy the full height of the panels, and the frieze as a whole represents a single episode and not a story. On the contrary, the treatment of the sculptures is by no means classical. The sculptors resorted to the technique of high relief, common in metopes but not in friezes. Likewise, they show a level of detail unusual in ornamental sculpture: the feathers, scales or skin of each of the monstrous giants are represented with great delicacy, as are the clothing and footwear of the gods. The characters are intermingled in a dense and complex composition, while the bodies of the giants convulse and their faces contort in pain before the assault of the Olympian gods.On the north face of the stairway, the gods push the giants up the stairs to corner them. As the viewer climbs the steps, his ascent is accompanied by the fall of the giants, who sink deeper and deeper into the steps.

The Pergamon style, which can be described as Hellenistic Baroque, reaches its apogee in this work. Indeed, the frieze is the largest and one of the last creations of the Greek monumental sculpture. The composition is very dense and seems to highlight the important function of the podium. The scenes, the figures and their faces are treated with pathos (emotion). The expressions of the gods and giants are characterized by a pathetic or exaggerated expression, with an open mouth, a frown, a wrinkled forehead, and a somber look. The giants' musculature is powerful, tense from the effort, almost swollen. The foreshortenings and stylistic details, such as the folds of the cloaks, the hair and the drawings of the footwear, as well as the sculpture of the clothes no longer conform to the anatomical forms. The demonstrations of force are charged with detail and psychological intensity. The victorious struggle of the Olympian gods against the chthonic forces undoubtedly seeks to symbolize the supremacy of the Attalid princes over the Galatian barbarians, although beyond any political reading, the composition possesses a cosmogonic meaning.

The East Frieze

The east frieze, which was the first one the visitor saw when they arrived at the agora, shows the main Greek divinities: Ares, Athena, Zeus, Heracles, Hera, Apollo, Leto and Artemis. To the far left, the frieze begins with the three-faced goddess Hecate. The three incarnations of her fight with a torch, a sword and a spear against the giant Clytius. Beside her appears Artemis, the goddess of the hunt, accompanied by her hunting dog with three giants. The goddess, armed with her own bow and arrows, tramples on the body of a dead giant, which could be Oto. In turn, the dog fatally bites another giant on the neck, which resists and fights the hound by gouging out one of its eyes with its claw. Artemis's mother, Leto, fights alongside her using a torch against a giant shaped of animal. On the other side of her also fights her son and Artemis's twin brother, Apollo. Like his sister, he is armed with a bow and arrows and has just shot the giant Udaios, who lies at his feet.

The next panel, supposedly depicting Demeter, is barely extant. The one on her side shows Hera, riding into battle in a chariot. Her four winged horses are identified with the personifications of the four winds: Noto, Boreas, Zephyr and Euro. He also participates in the Heracles fight, situated between Hera and her father Zeus. He has been uniquely identified by a frieze fragment showing the paw of his lion skin. Zeus is physically present and especially agile. He participates in the fight by throwing lightning and sending down rain and masses of clouds, not only against two young giants but also against his king, Porphyrion. The next pair of warriors also shows a particularly important battle scene. Athena, the goddess of the city of Pergamum, separates the giant Alcyoneus from the Earth, from which emerges the mother of giants, Gaea. According to the legend, Alcyoneus was immortal only while he remained in contact with the Earth, through which the power transmitted to him by his mother flowed. The figure of Athena is represented victorious, as highlighted by the presence of Nike, who he subdues a snake-bitten giant while Gaea comes to his aid. The east frieze concludes with Ares, the god of war, entering battle with a chariot and a pair of horses. They rear up in front of a winged giant.

The south frieze

The depiction of the battle begins here with the great mother goddess of Asia Minor, Rhea/Cybele. She comes to the fight with a bow and arrow, riding on a lion. On the left is the eagle of Zeus holding a beam of rays in its claws. At Rhea's side, three of the immortal characters fight an imposing giant with a short, thick neck. The first, a goddess, could not be identified. She is then followed by Hephaestus, who raises a double-headed hammer high. Next to him appears another unidentified god kneeling, who plunges a spear into the body of his adversary.

Next, the divinities of light appear: Phoebe ("the bright one") and Asteria ("starry"), Selene, Helios and Eos. Eos, goddess of the dawn, rides into battle riding the Amazon She holds her horse as she pushes forward a torch. She is accompanied by Helios, who emerges from the ocean with his chariot and joins the fight armed with a torch. Her target is a giant that appears in her path, as she runs over another of them. Thea follows him in the midst of her children, the stars of the day and of the night. Near her mother and with her back to the viewer, the moon goddess Selene rides her mule above a giant.

In the last third of the south frieze, an unidentified young god, possibly Aether, appears fighting. He holds in complete control a giant with the legs of a serpent, a human body, and the legs and head of a lion. The god next to him, obviously older, is supposed to be Ouranos. To his left is his daughter Themis, the goddess of justice. At the end (or at the beginning, depending on how you look at the frieze) are the titan Phoebe with a torch and her daughter Asteria with a sword, accompanied by a dog. The gods are grouped by an association of ideas, generally referring to their family ties. Thus Phoebe and Asteria, Leto's sisters, adjoin her at the corner between the east and south friezes.

The west frieze

On the west front of the altar, two protruding bodies that are the extension of the north and south façades finish off the access stairway on both sides. Each of these two wings is divided into three faces each: two sides and one front. Thus, the north wing is located on the left side of the stands looking in the direction of the ascent and the south, on the right side of the stairs. The frieze runs along the perimeter surrounding the bodies until it ends against the steps.

Left side or north wing

The north wing is made up of the marine divinities: Poseidon and his family, including Oceanus and Amphitrite with his son Triton, who fight against various giants. Triton's upper torso is human, the front of the lower torso is of a horse and the back of a dolphin. On the inner wall, in contact with the stairway, are the couple formed by Nereus and Doris, as well as Oceanus, and a fragment that is supposed to be from Thetis, all of them involved in fighting the giants.

The figures present their wet clothes that stick to their bodies; Nereus can even be seen with scales on his head and with fins.

Right side or south wing

Various nature gods and mythological beings gather in the south wing. On the frontal ledge, Dionysus joins the fight accompanied by two young satyrs.Next to him is his mother Semele, leading a lion into battle. The fragments of three nymphs are shown on the side of the stairway. In this place the only signature of an artist, THEORRETOS, was found on the cornice.

The North Frieze

Aphrodite begins the sequence of the gods on this north side. Since she must imagine the frieze as continuous, she must be close to her lover Ares, who completes this frieze. The goddess of love extracts a spear from a dead giant. Fighting next to her are her mother, the Titaness Dione, as well as her youngest son, Eros.The next two figures are uncertain. They are probably the twins Castor and Pollux. Castor is caught from behind by a giant that bites his arm, while his brother rushes to help him.

The following three pairs of warriors are related to Ares, the god of war, though it is unknown who they represent. In the first, a god is about to throw a tree trunk. In the middle, a winged goddess plunges her sword into her opponent, and the third scene shows a god fighting an armored giant. For a long time the goddess who follows them was considered to be Nix, but today it is assumed that she is one of the Erinyes, the goddesses of revenge. She is holding in her left hand a pot wrapped with snakes, preparing to throw it. Beside her, two other characters fight. The three Fates or Goddesses of Fate bludgeon the giants Agrio and Toante to death with bronze stakes.

Next is a group of combatants including a lioness goddess believed to be Ceto. This set does not immediately follow the Fates, instead there is a gap that probably contained another pair of fighters. They could have been the children of Ceto, the Grayas. Keto was the mother of several monsters, including a whale (Greek: Ketos ) that climbs at her feet. The north frieze closes with the god of the sea, Poseidon, emerging from the ocean with a group of seahorses. The next scene in the sequence is the ocean gods located in the north wing of the west frieze.

Authorship

For a long time, the identity of the sculptors in charge of creating the Gigantomachy has been analyzed, although very little is known about them. Only a few plates with their names have reached our days: Menécrates, Dionysiades, Melanippus, Orestes or Theorreto, although the name of the author who allowed the unification of the entire work is unknown. Likewise, the level of participation of each artist individually on the frieze, although there is consensus that at least its basic design was the work of a single sculptor. In view of its consistency at the level of detail, the scheme was probably followed down to the minor elements and nothing was left to chance. In the arrangement of the sets of fighters it is appreciated that each group is unique and that, for example, the style of the hair and footwear of the goddesses always differs. Each pair of warriors is arranged individually, so that the figures reveal a distinct character for themselves and not because they are the result of each artist's personal style.

Although experts have determined that there are real differences that can be attributed to individual artists, these are practically irrelevant given the coherence of the entire frieze when viewing the work as a whole.Under this interpretation, authors from different parts of Greece are they would have subordinated to a single artist with general authority. This would be confirmed by the inscriptions of various sculptors from Athens and Rhodes. They were allowed to sign on the lower molding of the part of the frieze on which they worked, but only a few of these notations have been found. Thus, no conclusions can be drawn about the number of participating artists. The only thing that remains is a sign on the protruding body that limits the stairway to the south, which has allowed its attribution. As there was no lower molding in that area, the name of Theorretus (ΘΕΌΡΡΗΤΟΣ) was carved on the marble near the god represented. When the various inscriptions were analyzed, it was determined by the font that there were two generations of sculptors working, one younger and the other older, which makes the coherence of the entire frieze more admirable. If one considers the distance from 2.70 meters between the existing signature and the associated inscription έπόησεν ("made by"), it can be assumed that another sculptor's name possibly existed in this space. In that case, it could be considered by extrapolation that at least forty sculptors would have participated. The central part of this projection was signed by two sculptors, although their names have not survived to this day.

The Frieze of Telephos

The Telephus frieze, about 80 meters long, dates from after the Gigantomachy and was left unfinished. It shows a more serene style and is characterized by a return to classicism. It is made up of panels 1.58 meters high, with a variable width between 75 and 95 centimeters and a thickness of 35 to 45 centimeters. The preserved part, which constitutes a third of the original frieze, has more than ninety figures, distributed in 47 panels of a total of 74 of which it was originally composed.

Part of the panels were discovered in a wall built in the 8th century to defend the city against the Arabs, located about 80 meters from the location of the altar. Experts agree that the frieze must have been linked to the great altar. Indeed, the altar is the only monument large enough to accommodate a work of such dimensions. In addition, the panels used were similar to those of the Gigantomachy.

The frieze was quickly identified as a Telefiada by an image showing Orestes being taken hostage by Telephus. It narrates the protagonist's life sequentially, from his birth to his death.The panels show the most important episodes of the legend: the oracle received by Aleo, Telefo's grandfather; the construction of the ship where Auge, mother of the hero, was abandoned; the reunion between Telefo and his father Heracles or the taking of Orestes as a hostage. In addition, the frieze alludes to the victories of Pergamum and the mythological origins of the city. The composition is narrative: each plate recounts an episode from the hero's life. The sculptors brought together various mythographic traditions, some of which do not survive as a continuous narrative. Thus, one of the images shows a priest accompanied by some satyrs, without knowing the role he plays in the legend of Telephus.

The panels are badly damaged and some of them are unfinished. While the Gigantomachy is distinguished by its narrative unity, the Telephus frieze has a variable theme, changing from time, place and setting from one image to another. In addition, the Telefiada shows landscape or architectural backgrounds, unlike the Gigantomachy. The figures are staggered in depth and architectural elements are used to indicate the activities taking place inside, while the landscapes are lush and panoramic. The sculptural style is more classical, with more restrained movements and expressions and more linear clothing, adapted to the shape of the figures. The relief is less pronounced, with which the effect of chiaroscuro is less noticeable.

Following a restoration in 1995, the panels were rearranged in their correct order. There are some gaps in the sequence since some of them were lost. The following list shows the established order:

Panels 2,3 - 2: In the court of King Aleus; 3: Heracles discovers Auge, the daughter of Aleo, in the temple.

Panels 4,5,6 – 4: The infant Telephus is abandoned in the wild; 5 and 6: the carpenters build a ship where Auge is left adrift.

Panel 10 – King Teutrante finds Auge stranded on the shore.

Panel 11 – Auge establishes the cult of Athena.

Panel 12 – Heracles identifies his son Telephus.

Panels 7, 8 – The nymphs bathe the infant Telephus.

Panel 9 - The childhood of Telefo

Panels 13, 32, 33 and 14 – Telephus travels by ship to Mysia in Asia Minor.

Panels 16 and 17 – Télefo receives Auge's weapons.

Panel 18 – Télefo goes to war against Idas.

Panel 20 – Teutrante gives Auge in marriage to Télefo.

Panel 21: Mother and son recognize each other on their wedding night.

Panels 22-24 – Nireo kills the Amazon Hiera, the wife of Telephus.

Panel 51 – The fight is interrupted for Hiera's solemn funeral.

Panel 25 – Two Scythian warriors fall in battle.

Panel 28 – The Battle of the Caicos Springs.

Panels 30, 31 – Achilles wounds Telephus with the help of Dionysus.

Panel 1 – Télefo consults an oracle about the healing of her wound.

Panels 34 and 35 – Telephus lands in Argos to meet Achilles, who is able to heal his wound.

Panels 36 and 38 – The Argives welcome Telephus.

Panels 39 and 40 – Telephus asks Agamemnon to heal his wound.

Panel 42 – Telephus threatens to kill Orestes, whom he has taken hostage to force Agamemnon to heal.

Panel 43 – The healing of Télefo.

Panels 44-46 – The founding of the Pergamum cults.

Panels 49 and 50 – The construction of the altar.

Panels 47, 48 – Women approach the hero Telephus, who is resting on a kline.

|

The collection of statues

On the roof of the altar were several small statues of gods, groups of horses, centaurs, and tawny griffins. The finds have not yet been accurately described by archaeologists in relation to their function and location. A 64 meter long pedestal, profusely adorned with sculptures, was also found on the north wall of the altar sanctuary. The extension of the area of the altar that would be provided with bronze and marble statues is still unknown. However, the ornamentation must have been extraordinarily rich and would have represented a large outlay on the part of the donors. The upper story above the Gigantomachy, where the Telephus frieze was installed, also had a circular portico, as well as possibly additional statues between the columns. This hypothesis is supported by 30 individual sculptures of women found among the finds, which could have personified the cities of the kingdom of Pergamum. It is believed that there were no statues or other decorations on the fire altar itself, although a canopy was probably installed in Roman times.

Contenido relacionado

Arthur (1981 film)

Zapatista

Rebel without a cause