Penuti languages

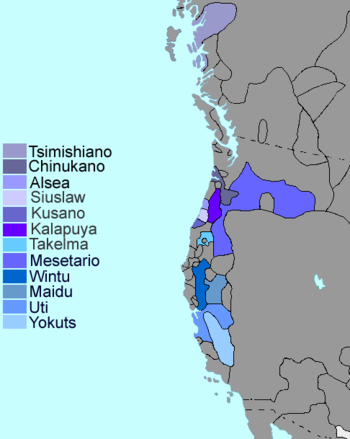

The Penutian languages or Penutian languages include a set of language families spread mainly through California, Oregon and, according to some proposals, also British Columbia, which share certain typological characteristics common and in the opinion of some authors they could form a genuine linguistic macrofamily, although this last point is controversial.

The name of this language family derives from the word two in certain Californian languages: pen (from wintun and maidu) and uti (from miwok-costano).

History of the hypothesis

The existence of a Penuti family, beyond its exact composition, has not been fully demonstrated in the opinion of all specialists. Even the phylogenetic unity of some of the families with the rest has been discussed. A number of the languages proposed as belonging to the Penuti set are extinct and poorly documented, leaving researchers with no new sources to work with. Another complication is the large number of loans that occurred between neighboring towns. Mary R. Haas proposes the following regarding this flow:

Even where the genetic relationship is clearly indicated [...], the evidence of the diffusion of the traits of neighboring tribes, related or not, is seen everywhere. This makes the task of determining the validity of several so-called hokan languages and several so-called Penptian languages much more difficult [...] [and] reveals once again that the difusion studies are so important to prehistory as genetic studies are, and what should be emphasized even more, reveals the desire to continue difusional studies along with genetic studies. This is especially necessary in the case of the Hokana and Penitia languages, wherever they are, but particularly in California, where they may have existed parallel for many millennia.Even where genetic relationship is clearly indicated... the evidence of diffusion of traits from neighboring tribes, related or not, is seen on every hand. This makes the task of determining the validity of the various alleged Hokan languages and the various alleged Penutian languages all the more difficult [...] [and] point[s] up once again that diffusional studies are just as important for prehistory as genetic studies and what is even more in need of emphasis, it points up the desirability of pursuing diffusional studies along with genetic studies. This is nowhere more necessary than in the case of the Hokan and Penutian languages wherever they may be found, but particularly in California where they may very well have existed side by side for many millennia.Haas 1976:359

Some clusters have been convincingly demonstrated. The Miwok and Costanan languages have been grouped into the Uti family by Catherine Callaghan. The evidence seems convincing for the grouping of the penutias of the plateau, originally called shahapwailutanas (English. Shahapwailutan) by J. N. B. Hewitt and John Wesley Powell in 1894, which would consist of the families klamath-modoc , molala and sahapatiana (Nez Percé and Sahaptin). There is growing evidence supporting the grouping of the Utis and Yokut languages (in the Yok-Uti group).

Beyond the Penuti languages of Canada and the United States, some authors have extended the number of families to truly distant languages, including languages from regions as far away from the northern Pacific coast as Oaxaca, Chiapas, or the Mayan region (and even in the macro-penutia hypothesis there is speculation as to whether languages from the southern cone, such as Mapuche, could be related to these languages, but these proposals are even more speculative and controversial and are decidedly only supported by a minority of specialists). More recent work has allowed some subgroups to be partially reconstructed, and there is some evidence that the Penuti family, as originally proposed, appears promising in certain respects and remains an active field of investigation.

The Five Main Families

The original hypothesis of the Penuti group, which would be composed of five language families, was proposed by Roland Dixon and Alfred Kroeber in 1903 and published in 1913. The evidence for this proposal was published in 1919. This, which has been alternatively called Central Penuti (English Core Penutian or Penutian Kernel) or California Penuti (English California Penutian ), is listed below.

- Maid languages

- Wintus languages

- Yokuts languages

- Miwoks languages

- Coastal languages

This grouping, like many of Dixon and Kroeber's other proposals, was based primarily on shared typological features, not on the usual methods of historical linguistics for determining strong genetic relationships. Since then, the Penuti hypothesis has been controversial, although some progress has been made in testing the soundness of part of the proposal by means of the comparative method.

Sapir's 1st Expansion

In 1916, Edward Sapir expanded the Penuti family of Dixon and Kroeber with a twin set, The Oregon Penutian Languages (Oregon Penutian), which includes the Coos languages and the isolated Siuslaw and Takelma leagues:

- A. Californians

- languages wintus

- languages maidus

- yokuts languages

- utis languages (miwok and costanoanas)

- B. Oregonian Penits

- kusanas languages

- siuslaw

- takelma

Sapir 2nd and 3rd expansions

Some time later, Sapir and Leo Frachtenberg added the Kalapuyan languages and the Chinuk (or Chinook) languages, and later the Alsean and Tsimshian families, culminating in Sapir's 1921 four-branch classification:

- I. Californian Penutio

- Wintuana (Wintu)

- Maiduana (Maidu)

- Yokutsana (Yokuts)

- Utiana (Miwok-Costanoan)

- II. Penutio oregoniano

- Cusana (Coos)

- Siuslaw

- Takelma

- Kalapuyana (Kalapuya)

- Alseana (Yakonan)

- III. Chinese family (Chinook)

- IV. Tsimshia family (Tsimshian)

By the time Sapir's 1929 article in the Encyclopædia Britannica was published, he had added two more branches:

- V. Messenger

- Klamath-Modoc (Lutuami)

- Waiilatpuana (Cayuse and Molala)

- Sahaptiana (Sahaptin)

- VI. Mexican Penutio

- Mixe-zoquena

- Huave

Resulting in a family of six branches:

- Penutí califoniano

- Penutí oregoniano

- Chinucana

- Tsimshia

- I thought of the plateau

- Mexican Penutí

Evidence in favor of the penutia hypothesis

It should be noted that the original motivations of Dixon, Kroeber and Sapir for grouping these languages together were fundamentally typological, and that the lexical evidence they initially provided was confusing and inconclusive. This situation was somewhat improved by extensive documentation during the 20th century, when stronger, though not entirely, phylogenetic evidence was proposed. convincing in assuring the kinship of all Penuti languages.

Perhaps due to the fact that most Penuti languages undergo morphological ablaut processes, vowels are difficult to reconstruct. However some phonetic correspondences between the consonants have been proposed, for example several retroflex */ʈ/ */ʈʼ/ of Proto-Yokuts seem to correspond to the affricates of the Klamath (penutium of the plateau) /ʧ ʧʼ/, while the proto-Yokut dentals */t̪/ */t̪ʰ/ */t̪ʼ/ correspond to the alveolar /d t tʼ/ of the Klamath. Apart from these correspondences the Kalapuya, the Takelma and the Wintu show no clear correspondences. Correspondences with the hypothetical Mexican penutium have not been adequately investigated. Another feature present in many Penuti languages is the presence of ablaut, which is why this fact is considered to be further evidence of the genuine kinship of the languages.

From archaeological and glottochronological evidence, it has been speculated that the Yok-Uti family has a divergence time comparable to that of the Indo-European languages, and that the linguistic ancestors of the Klamath would have remained in the same area for about 7000 years. Thus the linguistic depth of some branches of the penutia by themselves would exceed the limit that allows the adequate reconstruction of the proto-penutia. This has occasionally been used as an argument against the penutia hypothesis.

Modern synthesis

At present the validity of the Penutian hypothesis as extended by Sapir has not been confirmed, although it seems proven that the Californian Penutian languages are related. However, the Californian Penutian does not appear to be a phylogenetically valid subgroup as, for example, Maidu and Wintu appear to be closer to the Penutian languages outside California than to the Yokut, Miwok, and Costanoan families. To date, the proto-yok-uti has been reconstructed in some detail, and considerable progress has been made in the comparison of three other groups the wintu-maidu, klamath-sahaptin, takelmano and it is conjectured that the tsimishian, the chinuk and the alsea-siuslaw- coos could be independent branches but there are more doubts about the relationship of these last groups. By pooling the data from Delaney and Golla, a tree of possible relationships can be constructed:

The group called here "nuclear penutí" sometimes called "inside penutio" and the group "peripheral penutí" is called "maritime penutio". The names "penutio cismontano" and "penutio transmontano".

Macro-penutia hypothesis

A few linguists have suggested that other geographically distant languages of the Americas might be related to the Penuti group. This type of proposal includes Benjamin Whorf's macro-penuti hypothesis. Some of these proposals to the Penuti group within an even larger trunk called macro-Penutio that includes various Mesoamerican languages and the Totonac, Huave, and Mixe-Zoque language families. Geographically this macro-penutia family could be divided into the following branches:

- Canadian Northwest Group: tsimshian, spoken in British Columbia for a thousand people.

- United States Group:

- California Group: yokuts, maidu, wintu, miwok-costanoano.

- Meseta Group: klamath-modoc, sahaptin (including nez percé), cayuse-molala. All are extinct except the sahaptian language, which is spoken by a few hundred people.

- Oregon Group: coos, takelma, all extinct, in addition to chinuk (chinook) and tsimshian.

- Grupo macro-maya, from Mexico and Guatemala.

- Mayan, Mexican and Guatemalan languages.

- Mixed-Zoque languages of Mexico.

- Totonaco-tepehua languages of Mexico.

- Penutio Group of South America: it is a trunk that includes several small groups in Ecuador, Bolivia and Peru and the mapudungun, spoken by half a million people in Chile and Argentina.

Others have even produced hypotheses relating the Penuti to other large-scale families, such as Joseph Greenberg's Amerindian hypothesis.

Common features

The Penuti languages present a number of intriguing problems for both linguistic typology and historical linguistics. The original motivation for proposing the hypothetical Penutian family, for both Kroeber and Dixon and Sapir, was the anomalous typology within those of North American languages that these languages featured:

The penutio has an elaborate and subtle system of gradations or vocálica mutations. The etymological composition is undeveloped. The prefixes of any kind are completely absent. The name is provided with at least seven cases, and almost never more than seven. The verb does not express instrument or location, as it happens in other American languages, and it is only altered to express categories that basically reflects the indo-germic conjugation: intransitivity, inception and similar ideas; voice, mode and time, and person. He has a genuine passive voice...Dixon and Kroeber, 1913, p. 650

Equally from the point of view of the linguistic area, the Penuti languages present characteristics that are foreign to the other languages of California and the Pacific coast. For example, Nichols (1986) points out that many Penuti languages are exceptional in the area in that they present complement marking instead of core marking, which is the most abundant pattern in the languages of the region.

Although, of course, having in common a series of very special typological characteristics that distinguishes them from their neighbors is not a valid proof of linguistic kinship, the phenomenon requires an explanation. Of course a common origin could explain these typological patterns, but so would a complicated history of linguistic contacts leading up to the separation of the different groups to their current locations. Setting aside what appear to be more recent typological features and local developments, two features characterize most Penuti languages:

- the existence of morphological case in the name.

- the existence of vocálica alternations in the verbal root.

Those are precisely two characteristics that the ancient Indo-European languages also independently have, which is why Sapir compared them typologically. However, apart from these two characteristics there are other important typological differences with the Indo-European languages, with which there is certainly no demonstrable relationship.

In the examples that follow, the conventions of the American phonetic alphabet have been used preferentially, rather than the conventions of the international phonetic alphabet.

Phonology

A certain number of Penuti languages present ablaut as a productive morphological process. This, however, does not necessarily imply a genetic relationship but could be due to linguistic convergence typical of a linguistic area.

Regarding the morphophonology of the root, Dixon and Kroeber noted a tendency in the Californian penutio to have triconsonantal roots generally grouped in two syllables, both in the verb and in the noun. Biconsonantal stems are only frequent in maidu and could be thought to be the result of phonetic reductions. Although this fact in itself is not strong evidence of kinship, it is another series of unusual morphophonetic alternations that seem to recur throughout the family (shared morphological irregularities are known to be strong evidence of kinship). These alternations include reduplication of CV sequences, vowel harmony, ablaut, or floating (suprasegmental) glottalization. Sapir (1921) in his work on the Californian penutio, takelma and coos noted the prevalence of biconsonantal or triconsonantal disyllabic stems but with two identical vowels, i.e. CV1CV1(C), and suggested that this state of affairs might go back to proto-penuti. The same pattern was later witnessed in the Klamath, and the abundance of that pattern is compelling. Similarly Shipley (1966:491) detected regular correspondences between shortened forms of klamath of the form CCV(C) that seem to correspond to CVCV(C) forms in Californian penutium, a couple of very clear examples:

- (klamath) /snivolvq/ 'mucosity', (wintu) //iniq/ 'mucosity', (proto-miwok) /*sinak/ 'Sound your nose', (proto-yokuts) /*ṭhinik/ 'nariz'.

- (klamath) /wle/ 'correr (used for four-legged animals)', (maidu) /welé/ 'correr', (nez lost) /wîlé/ 'correr, move quickly', (takelma) /hi-wiliw-/.

To which other examples can be added:

- (klamath) /n ' s/ 'head', (maidu) / 'head'.

- (klamath) /wlep ' s/ 'rayo', (maidu) /wip`ili/ 'rayo', (proto-uti) /*wilep/ 'rayo'.

- (klamath) /t/alm/ 'West', (proto-yokuts) /*thoxil/ 'West.'

- (klamath) /nk’ey-/ 'fleight of war, bullet', (maidu) /nok/ 'flecha', (proto-yokuts) /*nek`i/ 'draw a bow' and /*nuk`on/ 'arco'.

- (klamath) /gmoc/ 'being old', (wintu) /qomos/ 'Mayor, old, old relative, ancestors'

Vocal mutations

Another of the typological characteristics of the Penuti languages, unusual in North America, is the presence of vowel alternations in the roots. These alternations include ablaut, vowel quantity variations, and vowel timbre variations, as well as various glottalizations. These phenomena occur especially in Miwok, Yokuts and Takelma, where they are systematic processes conditioned by certain suffixes and constitute an important part of verb inflection (a fact superficially reminiscent of Indo-European verb inflection, although there is no relationship between the two groups of verbs). languages). It is assumed that these alternations could be a retention of the proto-penutio, although for the moment it has only been possible to reconstruct the detail of these alternations for the proto-uti. Some examples of ablaut are:

- (takelma):

- ♪ 'excrement' / le- 'ano'

- laba-n ♪ take it ♪ libin "notices" (“what is taken”);

- yawa- 'talk' / yiwi- 'conversing' / yiwin 'talk, speech'

- (wintu):

- daq-al 'burning' / daq-ca 'burn, heat' / duc-a 'make a bonfire' / doci- 'brasas, ash'

- q`at-al 'Smoke' / q 'ut-e 'remove the water with your hands'

- -in-ca 'Sound your nose' / iniq 'mocos' / -un-a "sweep, swept your nose."

Instances of derivational ablaut also exist, present in many Penuti languages and reconstructable for Proto-Yokuts, Proto-Miwok and partially for Proto-Uti. The systematic use of ablaut is less widespread, although it is attested in Patwin, in some Uti languages and in Yokuts.

Vocal harmony processes were already identified by Dixon and Kroeber in Yokuts, Maidu and Miwok. Sapir studied the phenomenon in Yokuts and Sahaptin.

Grammar

The Penutian languages are not entirely typologically homogeneous, and the types found range from more analytic languages with inflection like the Kusan languages to polysynthetic languages like Chinook. However, three widely shared characteristics are:

- California's Puppet languages resort to ablaut and have grammatical cases, and are highly mergeant.

- The Penptian languages of California have grammatical concordance on the verb, although at the moment it has not been possible to rebuild the concordance system for the proto-penutio hypothetical. This is because it has been shown that some features of verbal morphology are recent: the evidence of the wintu could be due to contact with the pomo languages, while the verbal morphology of the klamath is also of recent origin.

- The names are marked by morphological case in all the Penptian languages of California and much of those of the Messary Penutio. Berman (1983:401-3) rebuilt case marks for the Californian proto-penutio (proto-PC), the following table compares some of the case systems:

CASO Proto-PC Wintu Maidu Sahaptin Klamath Molala Nez Percé Subject *- __ -(i)m __ __ __ Object *-Ø /*- -um -V - Yeah. -s / - coins - - Ergative (ablaut) -nim Absolute *-Ø Genitivo *-n / *-n -No. -k(i) -em - -(air)am /

- Call-(air)am -nim Instrumental *-ni -No. -ni Locative (1) *-in Locative (2) *-w -ūs

A single system for proto-penutian cannot be reconstructed with certainty (aside from the fact that it is not clear whether the original system was nominative-accusative, ergative-absolutive, or had split ergativity). Rude has proven that the case marks in sahaptin are of secondary origin and therefore do not date back to the hypothesized proto-penutian, making reconstruction difficult.

A more interesting fact is to explain the typologically unusual system of the maidu which marks the subject with -im. This form of the suffix is reminiscent of the gentive mark of other Penuti languages, a fact that does not seem accidental. Two explanations have been suggested: first, in many world languages subordinate clauses are realized as nominalizations with the subject expressed in the genitive accompanying the deverbalized predicative nucleus. Second, an alternative construction for a transitive construction with a passive sense in which the agent is marked in the genitive is abundant in several Penuti languages. For example, in Yokut languages there is a passive form with the agent marked in the genitive, as in the following examples taken from Chawchila and Wikchammi:

- (Chawchila)

- maxhan "-x ", nbsp;

- to seekDUR.AOR man...GEN

- 'He protected himself by man'

- (Wikchammi)

- p "ith navy " hane devoted

- chop.PSD Bee-GEN

- 'It was bitten by a bee' (= 'a bee bit him')

The same construction is found in Eastern Miwok, as in the following example from Southern Highland Miwok:

- j- developmenth-k- fashiona-ko teaspoon

- kill...PASIV-PSD.NOM floodingGEN

- 'They were killed by flooding' (= 'the flood killed them')

Similarly for the klamath, A. S. Gatschet documents genitive marking in the same situations:

- q Gadis-am brooki Gwog-atko

- snake.cascabel-GEN 2.aPER.SG morder-ESTATIV

- 'You've been bitten by a ravine snake'

All this evidence suggests that the maidu subject mark is a reanalysis of the genitive as a subject mark from old passive forms, as it appears in modern Konkow (Maiduan language), where the old genitive mark has been replaced by a new genitive form:

- kòle:-m-sa kóhunèje-k`i pépemàn

- That-boy-SUJ bigfoot-GEN eat-NOM

- 'That boy was devoured by the Bigfoot.'

Word formation

Many Penutian languages have really complex word formation processes. While most of the vowel alternations and mutations discussed above could be traced back to proto-penutian, much of the morphological complexity of words could be recent or secondary, particularly some words that are analyzable as ancient compounds.

Sapir characterized the Penuti languages as primarily suffixants. This is especially true for the Oregon Penuti languages, particularly Proto-Chinook, while the Tsimshianic group and Plateau Penuti are the least consistent with this generalization. Although for klamath and sahaptin it has been possible to determine that many of the prefixes are the result of recent nominal incorporation rather than genuine prefixes of Proto-Penutian origin. Similarly some of the "radical prefixes" of the wintu turn out to be originally independent elements, later incorporated and fossilized. For example the stem prefix yel- 'far, behind, backwards' from wintu has independent lexical cognates yal- 'leave, remove' or yal-a 'abandon, leave behind', yel-a 'go away, be away' and in Alsean yaːlaːs- 'to return, to return, to go home'. This suggests, therefore, that Proto-Penutian possibly used suffixes preferentially, prefixes in modern languages being the result of later compositional innovations and processes.

Contenido relacionado

Gallo-Romance languages

Icelandic name

Languages of switzerland