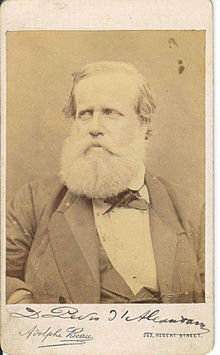

Pedro II of Brazil

Pedro II of Brazil (Rio de Janeiro, December 2, 1825-Paris, December 5, 1891), nicknamed "The Magnanimous", was the second and last monarch of the Brazilian Empire, having reigned in the country for a period of 58 years, he was the youngest son of Emperor Pedro I of Brazil and Empress Consort Maria Leopoldina of Austria and was therefore a member of the illustrious House of Braganza. The abrupt abdication of his father and his trip to Europe left Pedro with only five years as emperor, causing him to have a lonely childhood and adolescence.

Forced to spend most of his time studying in preparation for reign, he knew few moments of joy and friends his age. His experiences with palace intrigues and political disputes during this period had a great impact on shaping his character. Emperor Dom Pedro II became a man with a strong sense of duty and devotion to his country and his people. On the other hand, his role as monarch bothered him more and more. Born in the Imperial Palace of São Cristóvão, in Rio de Janeiro. The abrupt abdication of his father and his departure to Portugal made Pedro emperor when he was only five years old.

Despite inheriting an empire on the brink of disintegration, Pedro II transformed Brazil into an emerging international power. The nation grew differently from its Spanish American neighbors due to its political stability; to his freedom of expression, which was jealously maintained; respect for civil rights and its regular economic growth as well as its form of government: a constitutional parliamentary monarchy. Brazil emerged victorious in three international conflicts (the War against Oribe and Rosas, the Uruguayan War, and the War of the Triple Alliance) under his reign and prevailed in other international disputes and internal tensions. Pedro II firmly imposed the abolition of slavery despite the opposition of economic and political interests and earned a reputation as a great patron of knowledge, culture and science, as well as the respect and admiration of scholars such as Charles Darwin., Victor Hugo and Friedrich Nietzsche. He was a friend of Richard Wagner, Luis Pasteur, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, among others.

Although there was no desire for a change in the form of government among most Brazilians, the emperor was removed from power by a sudden coup d'état that only had the support of a small group of leaders military who wanted a republic ruled by a dictator. Pedro II had grown weary, disillusioned with regard to the future prospects of the monarchy despite popular support, and did not support any initiatives to restore the monarchy. He spent the last two years of his life in Europe living on scant means.

The reign of Pedro II had an unusual end as he was deposed when he was much loved by the people and at the peak of his popularity. He was followed by a period of weak governments, dictatorships, constitutional and economic crises. The men who exiled him soon made him a model for the Brazilian republic. Some decades after his death, his reputation was restored and his mortal remains were brought back to Brazil, where he is considered a hero and symbol of national identity.

Early Years

Birth

Pedro was born at 2:30 in the morning on December 2, 1825 in the São Cristóvão Palace in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. He was baptized in honor of Saint Pedro de Alcántara.

On his father's side, Emperor Pedro I, he was a member of the Brazilian branch of the Braganza Dynasty and his name was preceded by the honorary title don from birth. He was a grandson of the Portuguese King John VI and nephew of Miguel I. His mother was Archduchess Maria Leopoldina of Austria, daughter of Francis I, the last monarch of the Holy Roman Empire. On his mother's side, he was the nephew-in-law of Napoleon Bonaparte and cousin of Emperors Napoleon II of France, Franz Joseph I of Austria-Hungary, and Maximilian I of Mexico.

He was the only legitimate male child of Pedro I who survived infancy and was officially recognized as heir to the Brazilian throne with the title of prince imperial on August 6, 1826. Empress Leopoldina died on December 11 of 1826, a few days after giving birth to a stillborn child and when Pedro was only 1 year old. Therefore, Pedro had no memories of his mother except for what he was told about her. The influence and memories of his father faded over time.

Two and a half years after Leopoldina's death, the emperor remarried Amelia de Beauharnais. Prince Pedro did not spend much time with his stepmother either, although he had an affectionate bond with her and they were in contact until her death in 1873. Emperor Pedro I abdicated on April 7, 1831, after a long conflict with the Liberal faction (later to become the monarchy's two dominant parties, the Conservative and the Liberal) with power in parliament. He and Amelia immediately left for Europe where Pedro I was to restore his daughter Maria II to the throne of Portugal since it had been usurped by his brother Miguel I. The imperial prince Pedro then became Pedro II, "constitutional emperor and perpetual defender of Brazil".

Education

Before leaving the country, the emperor selected three people to take care of his son and daughters who remained in the country. The first person chosen was José Bonifácio, a friend and influential leader during Brazilian independence, who was appointed tutor. The second was Mariana Carlota de Verna Magalhães Coutinho, later Countess of Belmonte, who was Pedro II's governess from the birth of this. When he was a baby, he called her "dadama" because he could not pronounce the word "dama" correctly. He considered her his second mother and continued to call her that even as an adult. The third person chosen was Rafael, a black veteran of the Brazilian War. Rafael was an employee of the palace in whom Pedro I blindly trusted and asked him to take care of his son, which he did until the end of his days.

José Bonifácio was dismissed in December 1833 and replaced by another tutor. Pedro II spent his days studying and only had two free hours a day. He got up at 06:30 in the morning, began to study at seven and finished at ten at night, when he went to bed. His education was very well cared for to encourage values and a different personality from the impulsiveness and irresponsibility that characterized his father. His passion by reading allowed him to assimilate any type of information. However, Pedro II was not a genius, although he was intelligent and had a great capacity to accumulate knowledge easily.

The emperor had a lonely and unhappy childhood. The sudden loss of his parents would haunt him throughout his life; he had very few friends his own age and had limited contact with his sisters. The environment in which he was raised made him a shy and uncaring person who sought refuge in books and at the same time provided him with an escape from his real world.

Anticipated coronation

The enthronement of Pedro II in 1831 marked the beginning of a period of crisis, the most unstable in the history of Brazil. A regency was created to govern in his place until he reached the age of majority. disputes between political factions resulted in a series of rebellions and created an unstable, almost lawless situation under this period of regency.

The possibility of bringing the young emperor to the age of majority earlier, instead of waiting for him to turn 18 on December 2, 1843, had been considered since 1835. The idea was supported, to a certain extent, by the two main political parties. It was believed that those who helped him seize the reins of power would be in a position to manipulate the young emperor. Politicians who had emerged in the 1830s had become familiar with the dangers of ruling. According to historian Roderick J. Barman: “[the politicians] had lost all faith in their ability to run the country on their own. They accepted Pedro II as a figure of authority whose presence was essential for the survival of the country". The Brazilian people also supported the advancement of the age of majority, and considered Pedro II "the living symbol of the union of the homeland".; that position "gave him, in the eyes of the public, greater authority than that of any monarch".

Those who defended Pedro II's immediate declaration of coming of age drafted a motion asking the emperor to assume full powers. A statement was sent to the São Cristóvão palace asking if Pedro II would accept or reject bringing forward his coming of age He timidly answered yes to the offer and preferred that it take place that same day instead of waiting for his birthday in December. The next day, July 23, 1840, the Brazilian parliament formally declared Pedro II 15 years of age. In the afternoon, the emperor took an oath to the constitution. He was acclaimed, crowned and consecrated on July 18, 1841.

Consolidation

Marriage

The end of the regency stabilized the government. With a legitimate monarch on the throne, authority was clothed with a clear and unique voice. Pedro II understood his role as that of an arbitrator who put his ideas aside so that they did not affect his duty as moderator of political disputes between parties. The young monarch was dedicated and personally carried out daily inspections and visits to public administrations. His subjects were impressed with his apparent self-confidence, even though his shyness and lack of ability to function in different situations were seen as flaws. His reserved nature and the fact that he spoke with only one or two words made conversations extremely difficult. His taciturn nature was a manifestation of his fear of close relationships that had its origin in the experiences of abandonment, intrigue and betrayal that he had in childhood.

Behind the scenes, a group of high-ranking palace servants and political notables known as the "Courtier Faction" (Facção Áulica, in Portuguese) or "Club da Joana" because of the influence they had on the young emperor - and some were as close as Mariana de Verna - Pedro II was masterfully used by courtiers to eliminate his enemies (both real and supposed) by driving away rivals from he. Access to the monarch's person by rival politicians and the information he received were carefully controlled. A continuous round of government business, studies, events and personal appearances, used as distractions, kept the emperor busy, effectively isolated and prevented him from realizing how he was being exploited.

The courtiers were concerned with the immaturity of the emperor and believed that a marriage could improve his behavior and personality. The government of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies offered the hand of Princess Teresa Cristina. sent revealed that she was a young and beautiful woman, which led Pedro II to accept the proposal. They were married by proxy in Naples on May 30, 1843 and the new empress of Brazil landed in Rio de Janeiro. Janeiro on September 3. Upon seeing her in person, the emperor was disappointed since the portrait was clearly idealized; Teresa Cristina was a short woman, somewhat overweight and lame, and the emperor did not hide her disappointment. One of those present affirmed that the emperor turned his back on Teresa Cristina; another, that out of shock, the emperor had to sit down and it is possible that both things were true. That night, Pedro II cried and told Mariana de Verna: "They have deceived me, Dadama." Hours and hours went by necessary to convince him that duty required him to go ahead with the marriage. A nuptial celebration, with the ratification of the vows, was held the following day, September 4.

Establishment of Imperial Authority

In 1846, Pedro II had already matured physically and mentally. He was no longer the insecure 14-year-old who was carried away by rumors and hints of secret plots and other manipulative tactics. He had grown into a 1.93m tall, blue-eyed, blond-haired man, and was described as handsome by his contemporaries.

With his growth, his weaknesses disappeared and his qualities came to light. He learned not only to be fair and dedicated, but also to be courteous, patient, and sensible. As he began to fully exercise his authority, his newfound social skills and his dedication to government contributed greatly to his public image of efficiency.Historian Roderick J. Barman described him thus: "[Pedro II ] kept his emotions under strict discipline. It was never coarse and he never lost his mind. He was exceptionally clever with words and cautious in the way he reacted'.

At the end of 1845 and beginning of 1846, the emperor made a trip through the southernmost provinces of Brazil, passing through São Paulo, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. received in all the provinces. This encouraged him, for the first time in his life, to act with confidence on his own initiative. This period marked the end of the "Courtesan Faction". Pedro II successfully eliminated all influence that the courtiers had and removed them from his inner circle while avoiding a public disturbance.

Peter II faced three serious crises between 1848 and 1852. The first was the fight against the illegal slave trade from the African continent, which had been legally abolished as part of a treaty with Great Britain. it continued however and the British Parliament enacted the Aberdeen Act in 1845, which authorized British warships to board Brazilian cargo ships and capture those involved in the slave trade. In addition, on November 6, 1848, the Praieira revolt broke out; this was a conflict between local political factions in the province of Pernambuco that ended in March 1849. The Eusébio de Queirós Law was enacted on September 4, 1850, which gave the Brazilian government broad authority to combat the illegal slave trade. With this new weapon, Brazil eliminated the importation of slaves. This crisis ended in 1852 when Great Britain recognized that the slave trade had ended.

The third crisis was a conflict with the Argentine Confederation related to the ownership of the territories around the Río de la Plata and the navigation of its tributaries. During the 1830s, the ruler Juan Manuel de Rosas supported revolts in Uruguay and Brazil and only from 1850 was it possible for Brazil to face the threat posed by Rosas. An alliance was forged between Brazil, Uruguay and the rebellious Argentine provinces, which led to the war against Uribe and Rosas and the subsequent fall of the Argentine ruler in 1852.

The empire's success in all three crises greatly increased Brazil's stability and prestige. Internationally, Europeans began to see the country as a symbol of familiar liberal ideals, such as freedom of the press and constitutional respect for civil liberties. Its representative parliamentary monarchy was in stark contrast to the mix of dictatorships and instability in South American nations during this period.

Growth

Peter II and politics

By the early 1850s, Brazil enjoyed internal stability and economic prosperity. The country was being connected from one end to the other by railroad, telegraph, and steamship lines, and was becoming a single entity. For public opinion in general, both at home and abroad, these events were possible thanks to two reasons: "his government, which was a monarchy, and the personality of Pedro II".

Peter II was neither an ornamental figure like the monarchs of Great Britain nor an autocrat like the Russian tsars. The emperor exercised power through cooperation between elected politicians, economic powers, and popular support. This interdependence and interaction influenced the direction of Pedro II's reign. The emperor's most notable successes were achieved through the cooperation and non-confrontation with the facts with which he had to deal. He was very tolerant and rarely took offense at criticism, opposition or even incompetence, He was very careful when appointing candidates and only chose the most highly qualified. He also sought to eliminate corruption.He had no constitutional authority to force the implementation of initiatives without due support, and his willingness to collaborate allowed the nation to progress and allowed the political system to function successfully.

The insecurities of his childhood and the exploitation suffered during his youth caused the emperor to take control over his own destiny. In his view of his world, to achieve self-determination it was necessary to gain and maintain the necessary power.He used his active participation in the direction of government as a means of influence. His leadership became indispensable even though he never had a “one-man rule.” The emperor respected the prerogatives of the legislature, even when politicians resisted, delayed, or frustrated his goals and nominations.

The Brazilian national political system resembled that of any parliamentary nation. The emperor, as head of state, asked a member of the Conservative Party or the Liberal Party to form a government. The other party would go into opposition in the legislature, as a counterweight to the new government. "In his handling of the two parties, he had to maintain a reputation for impartiality, work in accordance with the popular will, and avoid any flagrant imposition of his will on the political scene."

Pedro II's active presence on the political scene was an important part of the government structure, which also included the council of ministers, the Chamber of Deputies, and the Senate. Most of the politicians supported the role of the emperor. Many had lived during the regency period, when the lack of a monarch who could stand above his own self-interest led to years of fighting between political factions. His experiences with public life gave him the conviction that the emperor was "indispensable to the peace and permanent prosperity of Brazil."

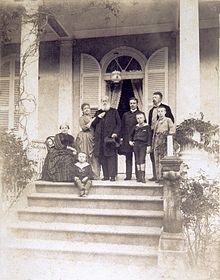

Domestic Life

The marriage between Pedro II and Teresa Cristina started badly, but with maturity, patience and, with the birth of their first son Alfonso, the relationship improved. Later, Teresa Cristina had three more children: Isabel, in 1846; Leopoldina, in 1847; and finally, Pedro, in 1848. However, both boys died in infancy, devastating the emperor.In addition to suffering as a father, his future vision of the empire was completely changed. Despite his affection for his daughters, he did not believe that Elizabeth, despite being her heir, had a real chance of succeeding on the throne. He believed that his successor had to be a man for the monarchy to be viable. He began to think that the imperial system was tied to his person and would not survive his death. Elizabeth and her sister received an exceptional education, even though they were not educated to govern the country. Pedro II deliberately excluded Elizabeth from participating in government affairs and decisions.

Around 1850, Pedro II began to have discreet love affairs with other women. The most famous and long-lasting of these relationships was with Luísa Margarida de Barros Portugal, Countess of Barral, with whom he maintained a romantic and intimate friendship, but not an adulteress, and made her a governess to his daughters in November 1856. Throughout his life, the emperor had hoped to find his soul mate, something he felt had been stolen from him by being forced into marriage by reasons of state with a woman for whom he never felt anything. These are just two examples that illustrate the double personality of the emperor; one was that of Pedro II who zealously carried the role of emperor that fate had imposed on him and the other was Pedro de Alcántara, who considered the imperial position a heavy burden and who felt happier in the worlds of literature. and science.

Pedro II was a compulsive worker and his routine was very demanding. He usually got up at seven in the morning and didn't go to bed until two in the morning the next day. He reserved his days for affairs of state and what little free time he had was devoted to reading and studying.The emperor wore a simple black tailcoat with black pants and tie every day. On special occasions he wore the dress uniform and only appeared dressed in the emperor's costume twice a year at the opening and closing of the General Assembly.

Peter II was as demanding of politicians and officials as he was of himself. The emperor required politicians to work eight hours a day and adopted a demanding policy regarding the selection of officials based on morality and merit To set an example, he adopted a simple way of life and dances and court events stopped since 1852. He also refused to increase his budget (800,000,000 reales a year), which was maintained stable since 1840 and went on to represent 3% to 0.5% of public spending in 1889. He also disliked luxury, as he understood luxury to be "useless spending and robbery Nation".

Patron of arts and sciences

"I was born to dedicate myself to letters and sciences," the emperor commented in his personal diary in 1862. He always found pleasure in reading and found a refuge in books. His ability to remember passages he had reading in the past was notable. Pedro II's interests were diverse and included anthropology, geography, geology, medicine, law, religious studies, philosophy, painting, sculpture, theatre, music, chemistry, poetry, and technology. By the end of his reign, there were three libraries in the São Cristóvão palace containing more than 60,000 books. His passion for linguistics led him to study languages and he was able to speak and write not only Portuguese, but also Latin., French, German, English, Italian, Spanish, Greek, Arabic, Hebrew, Sanskrit, Chinese, Provençal, and Tupi. He became the first Brazilian to acquire a daguerreotype camera in March 1840. He mounted a photographic laboratory in the palace of São Cristóvão and another of chemistry and physics. He also built an astronomical observatory in the palace.

The erudition of the emperor surprised Friedrich Nietzsche when they met. It happened during a trip through Europe organized by his Council of Ministers in 1870 during which he previously met Richard Wagner. It was 1871, Nietzsche was traveling on a train through Austria but account entered a private carriage by mistake, apologized but his host asked him to stay and they had a very pleasant conversation, after which Nietzsche was amazed by the erudition of his diner, whose identity he did not know at the time to get off the train. They would meet again in 1876, when the tetralogy of The Ring of the Nibelung was inaugurated at the Festspielhaus in Bayreuth. Victor Hugo told him: "Sir, you are a great citizen, you are the grandson of Marcus Aurelius", and Alexandre Herculano called him "a prince who is considered by general opinion to be the number one of his era thanks to a gifted mind and the constant application of his gift for science and culture". He was a member of the Royal So ciety, of the Russian Academy of Sciences, of the Royal Belgian Academies of Sciences and Arts, and of the American Geographical Society. In 1875 he was elected a member of the French Academy of Sciences, an honor that had only been received two other heads of state: Peter the Great and Napoleon Bonaparte. Peter II corresponded with scientists, philosophers, musicians and other intellectuals. He befriended many of his recipients including Richard Wagner, Louis Pasteur, Louis Agassiz, John Greenleaf Whittier, Michel Eugène Chevreul, Alexander Graham Bell, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Arthur de Gobineau, Frédéric Mistral, Alessandro Manzoni, Alexandre Herculano, Camilo Castelo Branco and James Cooley Fletcher.

Popularity and conflict with the British Empire

At the end of 1859, Pedro II left the capital to travel through the northern provinces. He visited Espírito Santo, Bahia, Sergipe, Alagoas, Pernambuco and Paraíba and returned in February 1860 after traveling for four months. The trip was a great success as the emperor was warmly received by all the places he passed through.

The first half of the 1860s saw a peaceful and prosperous Brazil. Civil liberties were maintained as Pedro II vigorously defended freedom of expression, which had existed since the independence of Brazil. National and provincial newspapers became an ideal medium for him to learn about public opinion and the situation general of the nation. Another means was direct contact with his subjects, which is why he organized public audiences on Tuesdays and Saturdays. Anyone, even slaves, could be received and present his petitions or tell his story.He also visited schools, prisons, exhibitions, factories and barracks and took advantage of these public appearances to gather first-hand information.

This tranquility disappeared when the British consul in Rio de Janeiro, William Dougal Christie, declared his willingness to provoke a war between his country and Brazil. The diplomat, who believed in gunboat diplomacy, sent Brazil an abusive ultimatum after two minor incidents that occurred between the end of 1861 and the beginning of 1862. The first was the sinking of an English ship off the coast of Rio Grande do Sul and looting of their property by local inhabitants; the second was the arrest of drunken British officers who rioted in the streets of Rio. The Brazilian government refused to relent, and William Dougal Christie ordered British warships to capture Brazilian merchant shipping as compensation. The Brazilian navy prepared for an imminent conflict and the emperor ordered the purchase of coastal artillery materiel. The battleships and defenses were given the authorization to open fire on any British vessel attempting to capture a Brazilian ship. Pedro II led Brazil's resistance and rejected any concession. This response came as a surprise to Christie, who changed his behavior and proposed a peaceful path and international arbitration. The Brazilian government presented its arguments and, seeing the position of the The weakened British government severed diplomatic relations with Great Britain in June 1863.

War of the Triple Alliance

The "voluntary patriot"

While the threat of war from the British Empire continued, Brazil had to pay attention to its southern borders as a new civil war began in Uruguay. The Brazilian government decided to intervene for fear of giving an image of weakness in the face of the British. The Brazilian army invaded Uruguay in December 1864 to carry out a brief victorious campaign that ended on February 20, 1865 with the overthrow of President Bernardo Berro and the imposition of Venancio Flores as dictator of Uruguay.

During this time, in November 1864, the government of Francisco Solano López was threatened by the Empire in its access to the sea, illegitimately overthrowing the white government of Uruguay allied with Paraguay, in addition to having ignored the government's ultimatum Paraguayan government against the Empire on its invasion of Uruguay, in defense of its dignity as a sovereign country, declares war on the empire and occupies part of Mato Grosso that was in dispute with the Empire of Brazil, which it had illegitimately usurped in 1804. The The Paraguayan government claimed legitimate possession of said territory, and had repeatedly tried to put an end to the dispute, but it was the Empire that evaded the resolution due to its insatiable greed for territories, supporting the unfounded thesis that the limit was the Apa River. In March 1865, the Paraguayan government declared war on Argentina, for refusing to give way through its territory to defend Uruguay, however, the Argentine government provided support to the Empire and even gave ammunition to the Brazilian army in its bombardment. to the Uruguayan city of Paysandú. Argentine President Bartolomé Miter hid the declaration of war to pass as a country attacked when the Paraguayan army occupied the city of Corrientes.

Aware of the anarchy that reigned in the region and of the inability and incompetence of the military chiefs to withstand the thrust of the Paraguayan army, Pedro II decided to go to the front in person. Although the Council of Ministers and Parliament refused. After receiving an unfavorable opinion from the Council of State, Pedro II made the following statement: "If I am prevented from going there as emperor, I cannot be prevented from abdicating and going as a voluntary patriot." Brazilians who volunteered for war became known as the "volunteer patriots", in homage to Pedro II. The monarch was popularly called "the number one volunteer".

Pedro II left the capital to the south in July 1865. He arrived in Rio Grande do Sul a few days later and continued his journey by land. At night, the emperor slept in a tent. Pedro II arrived in Uruguaiana, a Brazilian town occupied by the Paraguayan army on September 11. When he arrived, Paraguayan troops were surrounded.

The emperor went to assault Uruguayana with a rifle to demonstrate his courage but the Paraguayans did not attack him. To avoid further bloodshed, the emperor proposed to the Paraguayan commander that he surrender under honorable conditions, which he accepted. The coordination of military operations by the emperor and his personal example played a decisive role in repelling the Paraguayan invasion. It was then believed that the war was going to end and that López's surrender was imminent. Before leaving Uruguayana, the emperor received the British ambassador Edward Thornton, who publicly apologized to him on behalf of Queen Victoria for the crisis between the two empires. Pedro II considered that this diplomatic victory over the most powerful country in the world was enough and restored friendly relations between the two nations. He returned to Rio de Janeiro and was received as a hero.

End of Hostilities

Unexpectedly, the war continued for about five more years. During this period, the emperor devoted himself body and soul to continuing the war effort. He worked tirelessly to maintain and equip troops to reinforce the front lines and advance the construction of new warships. At the same time, he took pains to avoid disputes between political parties so as not to undermine the military effort. His refusal to accept a short-term result in order to achieve a total victory over the enemy was crucial to the final result. His tenacity ended. with López's death in combat on March 1, 1870, and the end of the war.

More than 50,000 Brazilian soldiers were killed in combat and the cost of the war was eleven times the government's annual budget. However, the country was so prosperous that the government was able to repay the war debt in ten years only. The conflict stimulated national production and economic growth. Pedro II rejected the Assembly's proposal to erect an equestrian statue with his effigy to commemorate the victory, preferring to use the money to build primary schools.

Heyday

An abolitionist on the imperial throne

The diplomatic victory over the British Empire and the military victory over Uruguay in 1865, together with the happy ending of the war with Paraguay in 1870, marked the beginning of what was called the "golden age" and the heyday of the Brazilian Empire The 1870s were happy years in Brazil and the popularity of the emperor was at its peak. The country made progress in the social and political spheres, and all layers of society benefited from reforms and the spread of growing prosperity. Brazil's international reputation, both for its political stability and its investment potential, increased considerably and the empire was considered a modern nation. The economy grew rapidly and immigration was expanding. New railway lines and new means of transport began to be built and other inventions such as the telephone and postal mail spread. «With slavery destined to disappear and other reforms in the pipeline, the prospects of "moral and material progress" they seemed huge."

In 1870, few Brazilians were opposed to slavery and even fewer dared to say so openly. Pedro II was one of those few and considered slavery a "national shame". Furthermore, the emperor had no slaves. In 1823, slaves were 29% of the Brazilian population, but this percentage was 15%..2% in 1872. However, the abolition of slavery was a sensitive issue in Brazil. Almost everyone, from the richest to the poorest, owned their slaves. However, the emperor wanted to end slavery progressively to lessen the impact of abolition on the national economy. He pretended to ignore the increasing damage that his support for abolition would cause to his image and that of the monarchy.

The emperor did not have the constitutional power to intervene directly and put an end to this practice. He had to use all his power to convince, influence and gain the support of politicians to achieve his goal. His first public gesture against the Slavery occurred in 1850, when he threatened to abdicate if Parliament did not declare the Atlantic trade illegal.

Once the arrival of new foreign slaves was prohibited, Pedro II addressed, in the early 1860s, the issue of the enslavement of children born to slave fathers. The law was drafted at the initiative of the emperor, but the conflict with Paraguay delayed the discussion in the Assembly. Pedro II publicly called for the progressive eradication of slavery in his throne speech in 1867, but he was strongly criticized and his decision was considered a "national suicide". She was reproached and made to know that "the abolition was her personal desire and not the nation's". The bill was finally approved and the free bellies law was promulgated on September 28, 1871. Thanks to her, all children born to slaves after this date were born free.

Trip to Europe and North Africa

On May 25, 1871, Pedro II and his wife left for Europe. The emperor had wanted to travel abroad for a long time. When he learned that his young daughter Leopoldina had died at the age of 23 in Vienna of typhoid fever on February 7, 1871, he had a compelling reason to venture outside the empire. When he arrived in Lisbon, he immediately went to the palace of Alvor-Pombal where he met his stepmother Amelia de Beauharnais. They had not seen each other for 40 years and the reunion was charged with emotion. Pedro II wrote in his diary:

I have wept with happiness and sadness seeing my mother so tender, but in turn, so old and so sick.

The emperor visited Spain, the United Kingdom, Belgium, the German Empire, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, Italy, Egypt, Greece, Switzerland and France. In Coburg he visited the grave of his daughter.This trip was for him "a moment of liberation and freedom." He traveled under the name of "Don Pedro de Alcántara", and insisted on being treated informally and was satisfied with staying in hotels. He spent whole days meeting with scientists and other intellectuals with whom he debated. His European stay it was a success; his attitude and his curiosity brought him the respect of the countries he visited. The prestige of Brazil and the emperor were reinforced during his tour and when he returned to Brazil the law of free wombs was ratified. The imperial couple returned to Brazil in triumph on March 31, 1872.

The problem with the bishops

Shortly after his return to Brazil, Pedro II had to face an unexpected crisis. The clergy had long been understaffed and understaffed, had discipline problems, and were poorly educated, leading to a loss of respect for the Catholic Church. reform program to remedy these problems. Since Catholicism was the state religion, the emperor exercised control over such matters as the payment of the salaries of the clergy, the appointment of priests and bishops, the ratification of papal bulls and the supervision of the seminaries. For the reform to be successful, the government appointed bishops who met its educational criteria, who supported its reforms and a return to moral values. However As the fittest men began to climb to the top of the hierarchy, a resentment against government control began to be felt.

The bishops of Olinda and Pará were two bishops of the new generation, of that educated clergy, of zealous Brazilian religious. They were influenced by ultramontanism, which was propagated within the Catholicism of the time. In 1872, they ordered that Freemasons be expelled from the brotherhoods of lay brothers. Although European Freemasonry had a tendency to espouse atheism and anticlericalism, things were quite different in Brazil where the Masonic orders were legion, although the The emperor was not part of any of them. The government tried to persuade the bishops to annul their decision, but they refused and were brought before the Superior Court of Justice. In 1874, they were sentenced to four years of forced labor, which the emperor converted into a prison term.Pedro II played a decisive role as he unhesitatingly supported the government's decisions.

Pedro II was a fervent supporter of Catholicism, since he considered that it ensured the important values of civilization and civility although he was quite orthodox in terms of doctrine and considered himself free to think and act. The emperor accepted the new ideas, such as Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, noting that "the laws that he [Darwin] has discovered glorify the Creator." He was moderate in his religious beliefs, but could not accept disrespect for the law. civil and government authority. As he told his son-in-law: "[The government] must ensure that the processes of the constitution are respected, there is no will to protect Freemasonry... but the objective is to defend the rights of the civil power". The crisis was resolved in September 1875 when the emperor decided to grant a complete amnesty to the bishops and annul their expulsion orders. The main consequence of the crisis was that the clergy saw no advantage in support Pedro II.They stopped supporting the emperor and waited for the arrival of his eldest daughter and heiress, Isabel, due to her declared ultramontane ideas.

Trip to the United States, Europe and the Middle East

The emperor went abroad again, this time to the United States. He was accompanied by Rafael, his faithful servant, who had raised him since childhood.Pedro II arrived in New York on April 15, 1876, from there to visit the country. He visited San Francisco, New Orleans, Washington and Toronto in Canada. The trip was a "great triumph", Pedro II made a great impression on the American people for his simplicity and kindness. He also crossed the Atlantic and he visited Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, Greece, the Holy Land, Egypt, Italy, the Austro-Hungarian Empire, the German Empire, France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Switzerland, and Portugal. September 1877.

His travels abroad had a profound impact on the emperor. He freed himself from the restrictions imposed by his function.Under the pseudonym "Pedro de Alcântara", he was able to move like a normal person and even traveled by train alone with his wife. It was only on these tours abroad that the emperor could abandon the formal existence and demands of life that he had in Brazil. However, it was more difficult for him to return to his role as head of state when he returned to Brazil. when his sons died, his faith in the future of the monarchy faded. His trips abroad made him deeply resentful of the weighty position he was given as a five-year-old boy. Since he had understood that he had no interest in keeping the throne for the next generation, there was no need to keep it for the rest of his remaining life.

Pacific War

The war in the Pacific between Chile, Peru and Bolivia aroused lively interest among Brazilian public opinion from the outset, and the emperor and his court spoke out in favor of Santiago's claims. Following the instructions of the emperor himself, the Brazilian minister Juan do Ponte Ribeyro made known to the government the content of the secret treaty signed by Peru and Bolivia in 1873, which was the basis for declaring war on both countries. Despite this, he avoided getting involved in the conflict.

Sunset and fall

Decay

During the 1880s, Brazil continued to prosper and the social composition of its population diversified enormously as the struggle for women's rights began to emerge. The letters written by Pedro II show us a cultivated man every time more fed up with the world and more pessimistic about its future. The emperor remained respectful of his duties and meticulous in carrying out the tasks assigned to him even if he did them without enthusiasm. Due to his growing indifference to the fate of the regime and his lack of reaction to opposition to the imperial regime, some historians attribute to him the "main, or perhaps the sole, responsibility" for the fall of the monarchy.

Knowing the dangers and obstacles of government, the politicians of the 1830s regarded the emperor as the primary source of authority indispensable to both government and national survival. However, this generation of politicians were dying out or they progressively withdrew from the government until, in the 1880s, it was practically replaced by a new group of politicians who had not lived through the regency or the first years of the reign of Pedro II, when external and internal dangers threatened the very existence of the nation. They had only known stable administration and prosperity. Contrary to those of the preceding period, the new politicians saw no reason to defend the imperial role as a unifying force beneficial to the nation. The role of Pedro II in carrying out national unity, stability and good governance had been totally forgotten by the ruling elites. Because of his humility, the emperor gave the impression that his role was useless.

The absence of a male heir to implement a new direction for the nation also diminished the long-term prospects of the Brazilian monarchy. The emperor loved his daughter Isabel very much, but he considered that a woman in power was impossible in Brazil. He considered the death of his two sons a sign that the empire was doomed. Reluctance to accept a woman as head of state was equally shared by the political establishment. Although the constitution allowed a woman to accede to the throne, Brazil was a very traditional country and would only have accepted a male successor as head of state.

Republicanism was an idea that had never prospered in the Brazilian elite and found little support in the provinces. However, the combination of republican ideas with the spread of positivism within the army and the base officers or middle ranks constituted a serious danger to the monarchy and led to indiscipline within the military corps. Some soldiers dreamed of a dictatorial republic that would be superior to the liberal and democratic monarchy.

Abolition of slavery and republican coup d'état

At the end of the 1880s, the emperor's health worsened considerably and his doctors advised him to go to Europe for treatment. Pedro II left Brazil on June 30, 1887 while Isabella remained at the helm. During his stay in Milan, the emperor hovered between life and death for two weeks and received extreme unction. While he was convalescing, in his hospital bed, he was informed that on May 22, 1888, the Slavery had been abolished in Brazil. With a weak voice and tears in her eyes, she said: "What a great people! What a great people!” He returned to Brazil and disembarked in Rio de Janeiro on August 22, 1888.

The whole country welcomed him with enthusiasm never seen before. From the capital, from the provinces, everywhere, there came evidence of affection and veneration.

The signs of devotion expressed by Brazilians for the return of the emperor and empress demonstrated the extent to which the monarchy seemed to benefit from unwavering support and was at the height of its popularity.

The country enjoyed significant international prestige during the last years of the empire, and was becoming an emerging power on the international scene. Predictions of economic chaos and an explosion of unemployment caused by the abolition of slavery did not materialize and the coffee harvest of 1888 was a great success. However, the end of slavery meant that the rich began to support Republicanism, especially the powerful coffee farmers who had great political, economic and social power in the country. They considered emancipation as the confiscation of a part of their personal assets. To try to dampen the Republican reaction, the The government used available reserves to make credit available to large coffee growers at reduced interest rates and negotiated the ceding of titles and honors to win back the favor of disgruntled influential political figures. The government also began to look indirectly at the problem of army to revitalize a dying National Guard.

The measures taken by the government worried the Republicans and the positivist military, but, nevertheless, they realized that these provisions undermined real power and favored their own ends, and the Republicans pressured the government to make similar decisions. The reorganization of the National Guard was launched by the government in August 1889 and the creation of a rival force prompted dissident officers to desperate measures. For Republicans and officers it was "now or never". Although the majority of the population had no desire to change the form of government, the republicans began to put pressure on the positivist military to end the monarchy.

Finally, the military carried out a coup and established the republic on November 15, 1889. At first, some people who saw what was happening did not conceive that it was a rebellion. The historian Lidia Besouchet affirms that: "a revolution was never so small." At all times, Pedro II did not show any emotion and cared very little about the future of events. politicians and military leaders to suppress the rebellion. When the emperor learned that he had been deposed, he simply said these words: "If it is so, I will go; I've worked a lot and I'm tired and I'm going to rest."

Exile and legacy

Last years

There was significant royalist resistance after the fall of the Empire, which was always suppressed. There were also anti-coup riots as well as battles between royalist army troops against republican militias. The "new regime suppressed with rapid brutality and with total disdain for all civil liberties any attempt to create a monarchist party or to publish monarchist newspapers". Empress Teresa Cristina died a few days after arriving in Europe and Isabella and her family moved elsewhere while her father He settled in Paris. His last two years of life were lonely and melancholic and he lived in modest hotels with almost no resources and writing in his diary his dreams in which he was allowed to return to Brazil.

One day he took a long ride along the Seine River in an open carriage despite the extremely low temperatures. Returning to the Bedford Hotel in the evening, he came down with a cold. The illness progressed in the following days until it became pneumonia. Pedro II's state of health deteriorated rapidly until his death at 00:35 on on the morning of December 5, 1891. His last words were: "May God grant me these last wishes for peace and prosperity for Brazil." While they were preparing his body, a sealed package was found in the room with a message written by the emperor himself: «It is the land of my fathers; I want it to be put in my coffin if I die outside my homeland". The package, which contained land from all the Brazilian provinces, was placed inside the coffin.

Princess Elizabeth wanted to hold a discreet and intimate ceremony, but ended up accepting the French government's request to hold a funeral for the head of state. The next day, thousands of personalities appeared at the ceremony held in the church of the Madeleine. In addition to the family of Pedro II, Francisco II of the Two Sicilies, ex-king of the extinct Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, Isabel II of Spain, ex-queen of Spain, Felipe de Orleans, count of Orleans, as well as other members of European royalty attended. Also present were General Joseph Brugère, representing President Marie François Sadi Carnot, the presidents of the Senate and Parliament as well as senators, deputies, diplomats and other representatives of the French government as well as almost all members of the French Academy, from the Institute of France and the Academy of Moral Sciences. Representatives of other governments, both from the American and European continents, made an appearance and even came from distant countries such as the Ottoman Empire, China, Japan, Persia. The coffin was transported in funeral procession to the train station, from where he would leave for Portugal. Despite the incessant rain and extremely low temperatures, about 300,000 people attended the event. The journey continued to the church of San Vicente de Fora in Lisbon and the body of Pedro II was deposited in the pantheon of the Braganza on December 12.

Members of the Brazilian republican government, "fearful of the great repercussions that the death of the emperor could have", refused to hold any official demonstration. In any case, the Brazilian people were not indifferent to the death of Pedro II because the «repercussion in Brazil was also immense, despite the government's efforts to minimize it. There were demonstrations of pain throughout the country: closed shops, flags at half mast, bells ringing for the deceased, black ribbons on clothing, religious services". "Solemn masses were held throughout the country, followed by panegyrics where to Pedro II and the monarchical regime".

Legacy

Brazilians remained attached to the figure of the popular emperor whom they considered a hero and continued to see him as the personified father of the people. This view was even stronger among black Brazilians or those of black descent who believed that the monarchy represented emancipation. The phenomenon of continued support for the deposed monarch is due above all to a widespread idea that he was "a wise, benevolent, austere and honest ruler". This positive view of Pedro II and the nostalgia for his reign also grew due to the fact that the The country began to suffer political and economic crises that Brazilians attributed to the fall of the emperor. The emperor never ceased to be considered a folk hero, but would gradually return to being an official hero.

Surprisingly, strong feelings of guilt were manifested among the republicans, which became increasingly evident with the death of the emperor in exile. They praised Pedro II, who was seen as a model of republican ideals, as well as the imperial era, which they considered to be an example for the young republic to follow. In Brazil, the news of the emperor's death "caused a genuine feeling of remorse among those who, despite not feeling sympathy for the restoration, recognized both the merits and the works carried out by their deceased ruler".

His mortal remains, as well as those of his wife, were finally brought to Brazil in 1921, in time for the centenary of Brazilian independence in 1922, as the government wanted to give Pedro II honors as head of state. It was declared a national holiday and the return of the emperor as a national hero was celebrated throughout the country. Thousands of people participated in the main ceremony in Rio de Janeiro. Historian Pedro Calmon described the scene: “The old people were crying. Many knelt. Everyone applauded. There were no differences between republicans and monarchists. They were all Brazilians." This tribute marked the reconciliation of republican Brazil with its monarchical past.

Historians hold Pedro II and his reign in high esteem. The historiographical literature dealing with him is vast and, with the exception of the period immediately after his fall, enormously positive and even laudatory. The Brazilian Emperor Pedro II is commonly regarded by historians as "Brazil's greatest man". Historian Richard Graham commented that "most 20th-century historians have looked at the period [of Pedro II's reign] with nostalgia but, in turn, to subtly, or not so subtly, criticize subsequent dictatorial regimes." in Brazil".

Offspring

From his marriage to Princess Teresa Cristina of the Two Sicilies he had four children:

- Alfonso, imperial prince of Brazil (23 February 1845–11 June 1847).

- Princess Isabel of Brazil (29 July 1846–14 November 1921), imperial princess of Brazil and Countess of Eu for her marriage to Prince Gaston of France.

- Princess Leopoldina of Brazil (13 July 1847-7 February 1871), married Prince Louis Augusto of Saxony-Coburg-Gotha.

- Peter (19 July 1848–9 January 1850). Imperial prince of Brazil from birth to death.

References in Modern Culture

Pedro II is a character in Civilization V and Civilization VI, Sid Meier's Civilization game saga of strategic genre published by Firaxis Games.

Ancestors

| Ancestors of Peter II of Brazil | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Contenido relacionado

West

Nasrid art

Zionism