Pedro Calderon de la Barca

Pedro Calderón de la Barca (Madrid, January 17, 1600 – May 25, 1681) was a Spanish writer, playwright and priest, member of the Venerable Congregation of Natural Secular Presbyters of Madrid Saint Peter the Apostle and Knight of the Order of Santiago, known primarily for being one of the most distinguished Baroque writers of the Golden Age, especially for his theatre.

Courtly poet and soldier, in 1651 he was ordained a priest. His theater, based on that of Lope de Vega, introduces important modifications: it suppresses unnecessary scenes and reduces the secondary ones; subordinates the characters to a central one; emphasizes monarchical ideas and the theme of honor. The baroque anguish of existence, together with theological problems, outline the sacramental plays, which require a great scenic apparatus and where Calderón reached his maximum lyricism. His language is the culmination of culteranismo and his expressive richness has elements of intellectual conceptism, Life is a dream (1635).

His works have been divided thematically: religious comedies (The devotion of the cross), historical-legendary (The siege of Breda), entanglement (House with two doors, it is bad to keep ), of honor (El médico de su honra), philosophical (The great theater of the world), mythological (Eco and Narciso) and auto-sacramental (To God for reasons of state).

Biography

Pedro Calderón de la Barca was born in Madrid on Friday, January 17, 1600 and was baptized in the parish of San Martín. His father, Diego Calderón, was a nobleman of mountain origin (Viveda, Santillana del Mar, Cantabria) and by paternal inheritance he had assumed the position of Secretary of the Council and Major Accounting Office of the Treasury, serving in it Kings Felipe II and Felipe III. Diego married Ana María de Henao in 1595, belonging to a family also of noble origin. Pedro was the third of the six children that the marriage managed to have, three boys and three girls, of whom only four passed from the childhood: Diego, the eldest; Dorotea —nun in Toledo—; Pedro and Jusepe or José. These siblings were always well-matched, as Diego Calderón declared in his will (1647):

We have always kept all three in love and friendship, and without making partitions of goods... we have helped each other in the needs and jobs we have had.

However, they also had a natural brother, Francisco, who they hid under the surname of "González" and he was expelled from his father's house by Don Diego, although he wrote in 1615 that he was recognized as legitimate unless he had married "with that woman whom he tried to marry", in which case it would be disinherited.

The lineage of the Calderón de la Barca family is very old and extensive. Fray Felipe de la Gándara wrote a book on this matter in 1661, whose chapter XII "De los Calderones de Sotillo, in the jurisdiction of Reinosa", is dedicated to the branch to which the playwright belongs. The family coat of arms consisted of five black pilot whales on a silver field and eight gold blades on a gules field on the border; It bore the motto "I will die by faith.

He started going to school in 1605 in Valladolid, because the Court was there, but his father, with an authoritarian character, decided to assign him to occupy the chaplaincy of San José in the parish of San Salvador that his grandmother Inés de Riaño had reserved and Peralta to the eldest son of the family who was a priest. Once in Madrid, the family settled in 1607 in some houses on Calle de las Fuentes that made the corner of the descent to the Caños del Peral. Pedro Calderón entered the Imperial College of the Jesuits in Madrid in 1608, located where the San Isidro Institute is now located, and remained there until 1613 studying grammar, Latin, Greek and theology. The extensive training he received there broadened his knowledge and reading, and decisively shaped his literary production and his life. When he had already been at the College for two years, his mother died of a miscarriage, as well as the girl she gave birth to (22 October 1610). In 1613 the grandmother Inés de Riaño also died and her will was opened, in which she declared her will that the eldest of her grandchildren occupy the aforementioned chaplaincy. Don Diego was unwidowed when he married for the second time in 1614 with the lady Juana Freyle Caldera, from a good but impoverished family; but his father too died suddenly and unexpectedly the following year, on November 21, 1615.

For this reason Pedro, who had entered the University of Alcalá the year before, had to interrupt his studies so that the abusive clauses of the will were read, which put the brothers against their stepmother, with whom they entered into a dispute. lawsuit even though they were minors (the eldest, Diego, was nineteen years old, but the age of majority was then granted to twenty-five), failed with a concert dated in Valladolid in 1618. Doña Juana remarried and the brothers were left since 1616 under the tutelage, education and maintenance of his maternal uncle Andrés Jerónimo González de Henao. In the interim, the future poet went to the University of Salamanca (1615), where in October 1617 he rented a house with other students, one of them his cousin Francisco de Montalvo, at the Colegio de San Millán. In June 1618 they still had not paid and were excommunicated.

Knight of the Order of Santiago, Capellán of Honor of S. M. and of New Kings in Toledo, Poet Cnomic in which he competed the ingenious invention, with the urbanity and beauty of the Language. He was born in Madrid year 1601, and died there at 81. Mariano Brandi engraving by drawing by Rafael Ximeno and Planes for the series Portraits of the illustrious Spaniards edited by the National Calcography between 1791 and 1819.

In 1619 he graduated with a bachelor's degree in utroque, that is, in both canonical and civil rights, without being ordained as his father had wished. In 1621 he participated in the poetic contest held for the beatification of San Isidro and later in his canonization, in 1622, and won a third prize.

He decided to give up religious studies for a military career and led a somewhat riotous life of brawls and gambling. There were also problems in the family sphere, since the brothers made an official declaration in 1621 of their state of hardship and had to sell a census or income from inherited goods in order to survive. In addition, in the summer of that same year he and his brothers Diego and José were involved in the murder of Nicolás Velasco, son of Diego de Velasco, servant of the constable of Castilla, and they had to take refuge in the house of the Austrian ambassador until they reached an agreement with the complainants that demanded the payment of a large compensation.

Perhaps because of these economic difficulties, Pedro had to enter the service of Bernardino Fernández de Velasco y Tovar, VI Duke of Frías and XI Constable of Castile, with whom he traveled through Flanders and northern Italy between 1623 and 1625 participating in various campaigns warfare, according to his biographer Juan de Vera Tassis, although there is no documentation to confirm it, and in 1625 he marched as a soldier in the service of the aforementioned Constable. His first known comedy, Love, Honor, and Power, was successfully premiered at the Palace on the occasion of the visit of Charles, Prince of Wales, on June 29, 1623, by the company of Juan Acacio Bernal; That same year followed Judas Macabeo, represented by Felipe Sánchez de Echeverría, as well as many others; in 1626 the eldest son Diego Calderón, already of legal age, was able to sell the office of Secretary of the Treasury Council of his father in the person of Duarte Coronel in exchange for 15,500 ducats; With this, the family managed to get out of their financial difficulties.

Since 1625, the date of his comedy La gran Zenobia, performed by the Andrés de la Vega company, Calderón provided the Court with an extensive dramatic repertoire: The siege of Bredá (1626), The Mayor of Himself (1627), The England Schism (1627), and, in 1628, Knowing Evil and the good, Poor man everything is traces, Luis Pérez, the Galician, and The Purgatory of Saint Patrick; but, in 1629, breaking into the sacred with his brothers chasing an actor, specifically in the Convent of the Trinitarians in Madrid, where Lope's daughter was, caused him the enmity of the monarch of the comic scene, Lope de Vega, and the famous Gongorian sacred orator Fray Hortensio Félix Paravicino. Calderón responded to the latter's attacks by mocking a passage in his comedy El príncipe constante, written that year, as well as La dama duende, his first great success. In that same year, 1629, he also premiered Casa con dos puertas, mala es de guardar and, in the Real Sitio de la Zarzuela, El jardín de Falerina. In 1630 he was already famous enough for Lope de Vega to praise his poetic talent in El laurel de Apolo and in 1632 he also earned the praise of Juan Pérez de Montalbán in his For all. Moral examples. In 1633 he wrote Amar después de la muerte o El Tuzaní de la Alpujarra , according to José Alcalá-Zamora & # 34; the most exciting tragedy of war and love in our literature & # 34;.

With these and other comedies, he even earned the appreciation of King Felipe IV himself, who began to commission him for the Court theaters, whether it was the golden room of the disappeared Alcázar or the recently inaugurated Real Coliseo del Buen Retiro, for whose first performance he wrote The new Retirement Palace in 1634. Likewise, Lope's star already eclipsed in the theaters, she earned the appreciation of the general public in the thirties with her pieces for the Madrid corrales de comedias de la Cruz and del Príncipe. In 1635 he was appointed director of the Buen Retiro Coliseum and wrote The greatest charm, Love, Life is a dream and The doctor of his honor, among many other highly refined dramatic shows, for which he had the collaboration of skilful Italian set designers, such as Cosme Lotti or Baccio del Bianco, and expert musicians for the first zarzuelas that were written, such as Juan Hidalgo. In these palatal commissions he took care of all the aspects and details of the representation and also attended the rehearsals. In 1635 it premiered on a floating stage in the Retiro pond The Greatest Love Charm, on the theme of Ulysses and Circe, with effects by Lotti, of which the Memory is preserved. for this piece. And on June 24, 1636, for example, another even more spectacular and complicated comedy was performed in the great courtyard of the Royal Palace on three aligned stages that developed three actions on three separate continents: Asia, Europe and Africa: The three greatest prodigies, also assisted by Cosme Lotti. Furthermore, Calderón was the one who signed the act of creation of the Spanish musical theater on January 17, 1657 by representing the first "zarzuela", El golfo de las sirenas, which was then called piscatory eclogue, in a place called La Zarzuela where theater companies used to go to entertain the Kings. It was a piece in one act with singing and music, and because of the place this genre of works would be called zarzuelas from now on. Of these he also wrote The laurel of Apollo and The purple of the rose , the latter, also in one act, already a true opera although still very brief. Its author called it "musical representation".

In 1636 he requested and obtained from the king the habit of knight of the Order of Santiago, for whose enjoyment it was necessary to request a dispensation from Pope Urban VIII, since his father had exercised the manual position of notary public, and, lifting the prohibition of Editing theater in Castilla, his friend and disciple Vera Tassis published the First part of his comedies and the second the following year, up to the nine that came to print, although another three printed by lesser publishers are preserved. careful. In 1677, the first part of his Autos sacramentales also appeared, the only one that he printed.

This First part includes Life is a dream and eleven other pieces, with their corresponding loas, which could be dated before 1630, according to Don Cruickshank. In 1637 he wrote El galán fantasma and entered the service of the Duke of Infantado and, although it is said that he distinguished himself as a soldier in the service of Admiral Juan Alonso Enríquez de Cabrera of Castile during the fight against the siege of Fuenterrabía (1638) that had been placed by the Duke of Enghien, future Prince of Condé, is not documented according to Ángel Valbuena-Briones; What is certain is that his brother José participated, who was wounded in the right leg; It is true that Pedro Calderón then composed a Panegyric dedicated to the aforementioned leader of the Spanish troops. On the contrary, he did participate in the war of secession in Catalonia (1640) in the cavalry company of cuirassiers under the command of Álvaro de Quiñones. He was at the capture of Cambrils and was wounded in the hand in a skirmish near Vilaseca, although the war was no less dangerous than his stay in the theatrical world of the Court: shortly before, in that same year of 1640, while rehearsing one of his comedies for carnivals in the Buen Retiro palace a dispute arose, there were stab wounds and Calderón was also wounded, something that José Pellicer de Ossau points out in one of his Notices, on February 20 specifically. He entered Tarragona victorious and behaved bravely in the assault on Martorell; After trying to besiege Barcelona, they had to return again to Tarragona, where Calderón withstood the siege of the French and Catalans, suffering from hunger and seeing several of his companions die from it. Finally, on August 20, 1641, the siege was rejected and Pedro Calderón returned to the Court to inform the Count-Duke of Olivares as His Majesty's courier. He later participated in the unsuccessful attempt to take Lérida (autumn 1642) as a squad corporal in the company of royal guards, in the vanguard of the cavalry led by Rodrigo de Herrera. He always kept a good memory of his military vocation, as he expressed in some famous verses:

This army that you see / vague to the ice and heat, / the republic better / and more political is / of the world, in that no one expect / to be preferred can / by the nobility that he inherits, / but by which he acquires; / because here to the blood exceeds / the place that one is made, / and, without looking at how he is born, / looks how it proceeds. / Here the necessity / is not infamy; and, if honored, / poor and naked a soldier, / has better quality / than the most gallant and lucid; / because here, to what I suspect, / does not adorn the dress the chest, / that the chest adorns the dress. / And so, of modesty full, / to the older you will see / trying to be the most / and to seem the least. / Here, the most principal / feat is to obey; / and the way it is to be / is neither to ask, nor to refuse. / Here, finally, courtesy, / good treatment, truth, / firmness, loyalty, / honor, bizarre, / credit, opinion, / constancy, patience, / humility and obedience, / fame, honor and life are: / flow of poor soldiers; / that, in good or bad fortune, / the militia is only one / religion of honest men.P. Calderon, Famous comedy. To overcome love, to defeat him, Valencia, 1689, but written in 1650

At that time, the Retiro Palace was expanded and a large pool of water was built, on whose central island the Love and Jealousy Contest would premiere in 1640. But, wounded during the aforementioned siege of Lérida, he obtained absolute leave or retirement in 1642 and in 1645 a life pension of thirty escudos a month as a reward not only for his services, but also for those of his late brother José in Catalonia, although he was paid badly and after repeated claims by the poet. He premieres his most ambitious works, those that require music (zarzuelas) and more scenery. Calderón was by then a discreet but active courtier and became a highly respected and influential character, a model for a whole generation of new playwrights and even for talents as great as those of Agustín Moreto and Francisco Rojas Zorrilla, his most important disciples. What's more, from 1642 an important series of French and English authors began to imitate his dramas and comedies without embarrassment, standing out especially for their constancy Antoine Le Métel d'Ouville, Thomas Corneille and François Le Métel de Boisrobert, while others imitate only loose parts. Among the English, William Wycherley stands out, whom he was able to meet in person in Madrid in 1664, when the Third part of his comedies was being published and he had come as a member of an embassy. This includes The Dancing-Master, from which he took the plot for his The Gentleman Dancing-Master (1672) and had also adapted Mornings in April and May in his Love in a Wood (1671). John Dryden and Aphra Behn were also inspired by their works premiered during Calderón's lifetime.

In the mid-forties, he became secretary to the VI Duke of Alba, Fernando Álvarez de Toledo y Mendoza, for a few years (from 1646 to 1649), for which he moved to his castle-palace in Alba de Tormes. Successive closures of the corrales de comedias are decreed due to the deaths of Queen Isabel de Borbón (between 1644 and 1645) and Prince Baltasar Carlos (between 1646 and 1649), also due to pressure from religious moralists opposed to the theater, so since 1644 there were no stage performances. With the death of his brothers José (1645) and Diego (1647), to whom he was so close, the playwright plunged into a crisis that coincides with that of Spain, between the fall of the Count-Duke of Olivares (1643) and the signing of in 1648 of the Peace of Westphalia. Moreover, around 1646 his natural son, Pedro José, was born, and Calderón had to rethink his life.

The internal and external crises ceased when the theaters reopened in 1649, the year in which The Great Theater of the World premiered; In addition, he entered the tertiaries (Third Order of San Francisco) on October 11, 1650 and was ordained a priest on September 18, 1651. It was precisely that year that El mayor de Zalamea was published under the title of The most well-given club and in 1652 it is represented in the Buen Retiro Coliseum The beast, the lightning and the stone. Shortly after (1653) he obtained the chaplaincy that his father so longed for the family, that of the New Kings of Toledo and, although he continued writing comedies (for example, in that same year he premiered La hija del aire) and hors d'oeuvres, from then on he gave priority to the composition of sacramental plays, a theatrical genre that he perfected and brought to its fullness, as it matched very well with his natural talent, a lover of painting and theological subtleties and complexities. As soon as he arrived in Toledo, he entered the Brotherhood of the Refuge, an institution that welcomed the poor and the sick and where years later his disciple Agustín Moreto would follow him. On the other hand, Cardinal Baltasar Moscoso y Sandoval commissioned him to compose some songs that would gloss the inscription Psale et sile or Canta y calla that is read over the choir doors of the Toledo cathedral.

He continued composing shows for the kings in the Buen Retiro Palace and for the theological festival of Corpus Christi, but now he leans towards mythological themes, thus fleeing his fantasy from a reality as harsh as that shown by the death of his son Pedro José was born in 1657 and the signing of the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659. At that time he was already the most celebrated playwright at court. In 1660 he wrote Jealousy even from the air kills, Céfalo y Pocris and The purple of the rose, and in 1661 he composed the mythological dramas Echo and Narcissus and The son of the Sun, Phaethon. Still in 1663 the King continued to distinguish him by designating him as his honorary chaplain, a fact that forced him to definitively transfer his residence to Madrid; in 1664 he published the Third part of his comedies, which include another masterpiece, In life everything is true and everything is a lie . The monarch's death in 1665 marked a certain decline in the pace of his dramatic output. He is named major chaplain of the new King Carlos II in 1666. In 1672 the Fourth part of his comedies is published and in 1677 the Fifth .

Throughout his theatrical career, he was sometimes bothered by the moralists who viewed theatrical shows with bad eyes, and especially that they were made by a priest like him. To them he replied haughtily in this way:

- «I, sir, always judged, allowing myself to carry human and divine letters, that making verses was a gala of the soul or agility of understanding that did not lift up or lower the subjects, leaving me to each one in the preaching that found him... And although it is true that idle courtiers treated her with the affection of skill found perhaps, I did not stop disdaining her on the day that I took the undeserved state in which today I see myself, for to return to her it was necessary that Mr.Don Luis de Haro send it to me from His Majesty... without having taken the pen for anything other than the feast of His Majesty or feast of the Most Holy... mereced [that]». (1651)

Despite so many honors, at the end of his life he suffered some economic hardships, to the point that in 1679 he was granted by royal decree a chamber ration in kind so that he could stock up on the palace pantry " in view of his services for so many years in this part and being at such a grown age and with very short means"; but on the occasion of the first marriage of Carlos II and on Carnival Sunday of March 3, 1680 he will compose his last comedy, Fate and motto of Leonido and Marfisa, inspired by the books of chivalry. It premiered at the Buen Retiro theater, with music by Juan Hidalgo, and the stage was directed by the famous painter Dionisio Mantuano, with José Caudi, a Valencian artist, constructing the scenery. In that same year he sent a list of his works to the Duke of Veragua, who had asked him for it, and the following year he wrote his last auto sacramental of his, The lamb of Isaías . After dictating his will on May 20, he died at half past twelve in the morning of Sunday, May 25, 1681, leaving half-finished the sacramental order commissioned for that year, La divina Filotea. His burial was austere and unostentatious, as he wished in his will: "Uncovered, in case it deserved to satisfy in part the public vanities of my ill-spent life." His body was buried in the chapel of San José in the church of San Salvador., where he was for one hundred and fifty-nine years. This is how the theaters were left orphaned by someone who was considered one of the best dramatic writers of his time.

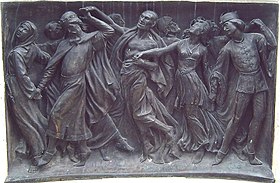

He bequeathed his assets to the Congregation of Natural Priests of Madrid, to which he belonged, and his manuscripts to his faithful friend, the priest of San Miguel, Juan Mateo y Lozano. In 1682, the vicar of Madrid commissioned a friend of Calderón's, the Trinidadian Fray Manuel de Guerra y Ribera, to draft an "Aprobación" to the True fifth part of comedies by Don Pedro Calderón, and his enthusiasm made him exceed so much that, instead of the few usual lines, he wrote an authentic 47-page apology for the theater of his time and especially that of his friend, which provoked some responses from the enemies of the theater. The house of Calderón de la Barca in which he lived and died in Madrid had two floors and was already in ruins in 1859; the writer Ramón Mesonero Romanos prevented its demolition, but two more floors and a commemorative plaque were added. It had a small balcony and was located on the old Calle de las Platerías, today Calle Mayor number 61. The people of Madrid dedicated a beautiful marble sculpture by Juan Figueras y Vila to his memory, which was placed in the Plaza de Santa Ana in 1880, opposite to the authentic Spanish Theater.

Work

Calderón de la Barca's play signifies the Baroque culmination of the theatrical model created at the end of the XVI century and beginning from the XVII by Lope de Vega.

According to the count that he himself made the year of his death, his dramatic production consists of one hundred and ten comedies and eighty sacramental plays, loas, hors d'oeuvres and other minor works, such as the poem Psale et sile (Sing and be silent) and more occasional pieces. Although he is less prolific than his model, the brilliant Lope de Vega, he is technically better than him in the theater and in fact brings the Lopesque dramatic formula to perfection, reducing the number of scenes in it and purifying it of lyrical and non-functional elements. turning it into a full baroque show to which he also adds a special sensitivity for the scenery and music, elements that for Lope de Vega had less importance.

He frequently uses previous pieces that he recasts, eliminating useless scenes; decreases the number of characters and reduces the polymetric richness of the lopesco theater. Likewise, he systematizes the creative exuberance of his model and builds the work around an exclusive protagonist. In a way, he purges Lope's theater of its most lyrical elements and always seeks the most theatrical. Ángel Valbuena-Briones has pointed out that in his style it is possible to distinguish two registers:

- In a first group of works Calderon reordena, condenses and reworks what appears in Lope in a diffuse and chaotic way, styling its coastal realism and making it more courteous. In them appears a rich gallery of representative characters of his time and his social status, all of which have in common the three themes of the Spanish Baroque theatre: love, religion and honor.

In the cultivation of this last theme, Calderón stands out in works such as The Mayor of Zalamea, in which individual honor (or what is the same, human dignity, not social custom or externa) of a rich farmer, Pedro Crespo, whose daughter has been raped by an aristocratic captain of the tercios of the famous general Don Lope de Figueroa, with the corporate honor or esprit de corps of the latter. In this drama, one of Calderón's masterpieces shows off the human truth of the characters and the wisdom and experience of the hero, Pedro Crespo, who thus advises his son Juan before he goes to the militia with some justly famous verses:

By the grace of God, John, / you are of clean lineage, / more than the sun, but villain. / The one and the other I tell you; / that, because you do not humiliate / so your pride and your cold, / that you leave, distrusted, / to aspire with arduous sane / to be more; the other, because / do not come vanished / to be less. Likewise / use inward designs / with humility; for, being / humble, with upright judgment / you will remember the best / and as such, in forgetting / you will put things, which happen / backwards in the alivas. / How many, having in the world / some flaw with it, / have blotted him out for humble; / and how many, who have not had / flaw, have found him, / for they are ill seen! / Be polite on manner; / be liberal and scattered, / that the hat and money / are those who make friends; / and it is not worth as much gold / that the sun begets in the Indian / soil, / Do not speak evil of women; / the humblest, I tell you, / that is worthy of estimation; / for at last we were born. / Do not laugh for anything; / that when in the peoples I look at / many, that to reñir they are taught, / a thousand times among me I say: / "That school is not / that it is to be". For collision / that it is not to teach a man / with skill, gala and cold / to gird, but to why / to gird; that I affirm / that, if there were a teacher alone / to teach prevented, / not how, why he laughs, / all would give him his children.

On other occasions, he addresses the passions of love that blind the soul, especially the pathological jealousy that he addresses in The Greatest Monster, Jealousy or in The Doctor of His Honor, among other dramas.

- In his second record, the playwright invents, beyond the cavalry repertoire, a poetic-symbolic form unknown before him and which configures an essentially lyric theatre, whose characters rise to the symbolic and the spiritual. He then fundamentally writes philosophical or theological dramas, sacramental selfs and mythological comedies or patellas.

Calderón stands out above all as the creator of those baroque characters, intimately unbalanced by a tragic passion, who appear in The Constant Prince, The Prodigious Magician or The devotion to the cross. His best-known character is the torn Segismundo de Polonia from La vida es sueño , considered the masterpiece of Calderonian theatre. This work, paradigm of the genre of philosophical comedies, collects and dramatizes the most transcendental issues of its time: freedom or the power of the will in the face of destiny, skepticism in the face of sensible appearances, the precariousness of existence, considered as a simple dream and, finally, the consoling idea that, even in dreams, one can still do good. This work has several versions made by himself. Also noted in it, although in the background, is the theme of education, so developed later in the XVIII century.

In this second register, he brings to perfection the so-called auto sacramental, an allegorical piece in an act with a Eucharistic theme intended to be performed on Corpus Christi day. To mention just a few, we will cite The Great Theater of the World or King Baltasar's Dinner.

As for philosophical dramas, his masterpiece is undoubtedly Life is a dream; The Doctor of His Honor and The Mayor of Zalamea in terms of honor drama, although there are also comparable pieces such as The Painter of His Deshonra (h. 1648) or A secret injury, secret revenge (1635).

The Open Secret and The Goblin Lady are pinnacles of sitcom, with many lesser-known swashbucklers such as The Hidden and the covered one , There are no jokes with love , A house with two doors is bad to keep or Mornings in April and May , that anticipates the genre of figurón comedy, although a piece of his such as Guárdate del agua mansa already has one, the quirky Don Toribio de Cuadadillos.

There are melodramatic comedies such as There is no such thing as keeping quiet (c. 1639), The worst is not always true (between 1648 and 1650) or The Gómez Arias's girl (c. 1651), who possess greater introspection and approach the tragic universe.

Palatine comedies are The ghostly gallant (1629), No one trusts his secret, White hands do not offend (c. 1640), or The open secret (of which an autograph manuscript from 1642 is preserved).

He approached historical drama with pieces such as The Great Zenobia (1625), The England Schism, Loving After Death, or The Tuzaní de the Alpujarra (1659) or The biggest monster in the world (1672).

Philosophical and symbolic dramas are The daughter of the air in its two parts, which depicts the boundless ambition of Queen Semiramis, the murderer of her husband Nino, and The Chains of the Demon (of doubtful attribution).

Religious and hagiographic dramas are The Devotion of the Cross (h. 1625), The Purgatory of Saint Patrick (1640), The Constant Prince (c. 1629), whose representation had such an influence on the theatrical conception of Jerzy Grotowski, and The Magical Prodigious (1637), a work that powerfully influenced Faust from Goethe, to whom he lent some entire passages.

Calderón became interested in mythological comedies when he replaced Lope de Vega in 1635 as chamber playwright. He quickly adapted to the conditions of the great courtly show with pieces such as The greatest charm, Love, from that year, and others such as The gulf of the sirens, The garden monster, Beasts make love effeminate, The beast, the lightning and the stone (1652) or The purple of the rose (1660) among many others. Of this genre is the opera, with music by Juan Hidalgo, Celos aun del aire matan, which Calderón himself parodied in his burlesque comedy Céfalo y Procris.

But the genre that the maestro monopolized was that of sacramental plays, from those with a medieval air such as The Great Theater of the World (considered by critics as his masterpiece in the genre) or The great market of the world to those with a mythological pretext, such as Andromeda and Perseus or Psyche and Cupid. Others: King Baltasar's dinner, Life is a dream, The Divine Orpheus (of which he made two versions separated by almost thirty years), The Merchant's Ship (1674) and so on. Calderón is the undisputed master of this genre, in which the characters have already become pure conceptual or passionate abstractions.

Calderón also composed quite a bit of minor theater, for example hors d'oeuvres such as El triunfo de Juan Rana.

Another classification is as follows:

- Tragedies: The doctor of your honor, Secret aggrieved, secret revenge; The painter of his dishonor; The daughter of the air;

- Serious comedy: Life is sleep; The mayor of Zalamea; The magical wonder.

- Comedias cortesanas: The Son of the Sun, Faeton. The beast, the lightning and the stone; The Garden Monster; Eco and Narcissus.

- Coat and sword comedies: The mistress; House with two bad doors is to keep; There is no mockery with love.

- Mythological Comedy: The greatest charm, love.

- Sacramental cars: The Great Theatre of the World; The Great Market of the World; The Supper of King Baltasar; The Protest of Faith; The True God Pan.

Calderón's comic theater

For a time, Calderón's comic theater was underestimated, but lately it has been revalued, since he certainly composed masterpieces in the genre that can be classified as sitcoms, such as La dama goblin, House with two doors, it is bad to keep or The ghostly gallant, and he did not neglect the minor theater.

Calderón's characters

Although Calderón sometimes knows how to succeed in creating human and unforgettable characters, like Pedro Crespo, most of the time what Marcelino Menéndez Pelayo said is true:

Calderon's characters hardly match the natural and simple expression, but replace it with hypter trees, discreet, subtleties and metaphor rain... They have relative and historical truth, they lack the human, absolute and beautiful truth that explodes in the roars of lion of the characters of Shakespeare.

Similarly, Calderón's characters have been compared to some of his contemporaries. Harold Bloom, analyzing the components of Goethe's work, takes the example of Faust and superimposes its protagonists with those of Calderón:

In the great works of Calderón as in the Fausto, the protagonists move and have an undetermined scope between the character and the idea; they are sustained metaphors of a complex of thematic concerns. This works wonderfully in the cases of Calderon and Lope de Vega, but Goethe wanted to alternate the two forms of personalities and themes, and he took the liberty of abandoning the Chaldean model and returning to the shakesperian cosmos whenever he came to him.Harold Bloom (1994)

On the other hand, Calderón's female characters are excessively masculine and do not possess the femininity and natural liveliness of Lope's women, although, when it comes to women invested with authority, this defect becomes a virtue, and thus we find true incarnations of ambition, such as Queen Semiramis in the two parts of The Daughter of the Air.

In the men's section, Calderón has a repertoire of unforgettable characters such as Segismundo, Don Lope de Figueroa, Pedro Crespo, the Constant Prince or that prototype of one of Calderón's most frequented characters, the crazed jealous husband who represents the Don Gutierre from The Doctor of His Honor; these pathological zealots that abound in Calderón's dramas reason fiercely, but the conclusions of his syllogisms are based on suspicions and unleashed passions, so that the result of his long musings leads to dramatic absurdity; that is why Calderón finds tragic substance in them.

Calderonian dramaturgy

Calderón reduces the number of scenes that Lope de Vega and his followers usually used, because he takes more care of the dramatic structure; he also restricts the abundant polymetry of the previous theater to eight syllables, hendecasyllables and sometimes seven syllables; he also impoverishes the strophic repertoire in order to achieve more unity of style. Instead of looking for new themes, which he too, he prefers to use themes already developed by Lope's previous comediographers or his school, which he rewrites by deleting useless, weak, redundant or non-functional scenes, or adding those that he believe necessary; that is, recasting them. For the rest, it follows the same mechanisms and conventions of the lopesca comedy, with the added contributions of Antonio Mira de Amescua, Tirso de Molina and Juan Ruiz de Alarcón, but sometimes mocking those mechanisms resorting to meta-theatricality. His style uses the formal finery of culteranismo, but also vulgarizes it with a series of metaphors around the four elements that all his audience could understand, which makes it more accessible. Likewise, he uses symbols in his comedies, many times taken from the Neoplatonic philosophy that influenced him so much: the fall of the horse, which represents dishonor or alteration of the natural order; not accidental coincidences, the deep meaning of light and darkness; the natural balance between the four elements, and some dramatic techniques such as the initial prophecy or horoscope in the play, which creates misleading expectations for the public, for example in The Schism of England or in the same Life is a dream. Calderón sometimes realizes how artificial and mechanical the baroque dramatic formula is and for this reason he sometimes allows himself to play games or meta-theatrical jokes, allowing his actors to make humorous comments about the topics that come their way and they are forced to follow..

With Calderón de la Barca, set design —what he called "memory of appearances"— and music (Calderón is considered the first author of zarzuela librettos) acquired full relevance in baroque comedy, in search of a integral baroque spectacle that united the diverse plastic arts. To this end he collaborated closely with Italian set designers such as Cosme Lotti. Theatrical ephemeral carpentry became a key element in the composition of his works, especially the sacramental plays, which were thus transformed into complex allegorical emblems pregnant with moral symbolism:

- The itinerary of the Spanish dramatic school described a circular line that begins with the idea of representation as a mirror of customs to conceive gender as an art that creates a poetic-ideological reality. In other words, the open art of Lope de Vega was passed into the intellectual, perfect, dehumanized manner of Calderón, which reached universal value through the emblem and symbol.

Language and style

As for its language, it is handled with solemnity, emphasizing beauty with the use of antitheses, metaphors and hyperboles; Calderón shines his mastery of rhetoric and, although it could be estimated that he is the theatrical culmination of culteranismo, he ensures that the metaphors can be easily unleashed by his audience, reiterating a mechanical system of cross references around the four elements and resorting to a Rhetoric of easy parallelisms, oppositions, symmetries and disseminations and collections, or repeating the concepts so that they fit and are understood:

- In one day the sun shines / and fails; in one day it breaks / a kingdom all; in one day / it is building a rock; / in one day a battle / loss and victory bears; / in one day has the sea / tranquility and storm; / in one day comes a man / and dies; then I could / in one day see my love / shadow and light, like planet; / sorrow and bliss, as empire; / people and brus / And having had age / in one day your violence / to make me so disdained, / why, why could not / be old in one day / to make me happy? Is it strength / begetting slower / glories than offenses? (P. Calderon, The mayor of Zalamea, 969-994)

He uses cultisms without embarrassment, some even condemned by Lope de Vega in his New art of making comedies (1609), as a hippogriff. In his characters a characteristic reasoning frenzy is accused: the Calderonian characters think in an iron and impeccably logical way, although their premises are in fact absurd; In this way, the characteristic Calderonian husbands go crazy with jealousy and justify their crimes in an impeccable but ethically absurd way, abounding in their language links of causal, consecutive, conditional, concessive or final logical subordination. Metaphorization also undergoes this process of mechanical logicism and exclusively develops the aforementioned system of symbols based on the combinatorics of the four elements. Metatheatrical games abound, since the author himself did not hide the convention that the lopesca formula had reached:

- Steril poet is this / because in a field he lacks / yedra jasmine or arrayan / to hide some ladies [...] But don't you see that we're behind San Jerónimo, and that's enough / that pretends tapes? And even those / pray to heaven that there are (P. Calderon, Poor man all traces)

- ARCEO: And if the galan and the lady are already deluded, / here the comedy ends. / DON PEDRO: Have you heard the disappointment yet, Don Juan? / DOÑA ANA: I'm not so happy.. / DON PEDRO: How so? DOÑA ANA: Like when / I came in, I only saw a man/who, daring and reckless, / threw himself out the window / there, sir, on those roofs. / ARCEO: Well, it doesn't end the comedy... (P. Calderon, Mornings in April and May)

Fragmented dialogues "hand in hand" are also frequent, in which two or more characters continue and finish the sentences that they leave half successively and symmetrically. On the other hand, Calderón's intratextuality is very strong, since the author sometimes reuses or rewrites texts from some comedies or plays in others, self-parodying with comic intentions or consciously imitating himself.

Especially in his minor theater, his use of comedy comes to be almost ubiquitous in the mouth of the humorous, subverting, among other conventions, the sacred sense of honor through the mechanism of oblique parody And so, in El toreador, when a nobleman says to Juan Rana: And honor, honor? Am I listening to you?, he answers: You say well: honor squeezes me a lot, which he reiterates on another occasion: Reputation has set / in such a tight lance / that honor is the least of it. As for the nobility of blood, it is well said in The House of Lineages: "Is there a person of more blood / than a mondonguera?". Even macho patriarchalism is subverted, and when Juan Rana's wife insists that he avenge his tarnished honor, he says: Challenge him, it's your turn (P. Calderón de la Barca, Juan Frog's challenge).

But the resource that Calderón resorted to most confidently, because it satisfied his desire to play with abstractions and concepts (something he could also exercise in mythological comedy) was allegory. In fact, he already definitively configured the genre of the auto sacramental on this resource, an allegorical piece in an act with a Eucharistic theme that was represented on the Christian festival of Corpus Christi, with great stage equipment. Calderón defined it like this:

- The allegory is no more / than a mirror that moves / what it is with what it is not, / and it is all its elegance / in which it comes out similar / so much copy on the table / that the one that is looking at a / think that is looking at logs (P. Calderon, The True God Pan)

But Calderón did not hide the conventional artificiality of the genre and mockingly summarized it, again through the use of meta-theatricality:

- ...I was in style, / that Man began sinning, / that God ended redeeming / and, when the bread and the wine came / to go up with him to Heaven / to the son of the gossip... (P. Calderón de la Barca, What goes from man to God)

Themes and ideology

Education in schools of the Society of Jesus of Calderón led him to assimilate the thought of San Agustín and Tomás de Aquino through the interpretation of Domingo Báñez, Luis de Molina and Francisco Suárez, and thus Menéndez Pelayo believed him to be Aristotelian. The most recent critics (Michele Federico Sciacca, Jack Sage, Ángel Valbuena-Briones) have also valued the enormous importance that Neoplatonic philosophy had for Calderón. Along with this, a deep pessimism is perceived in his theater despite the autonomy and validity of human action. His works usually focus on the opposition or confrontation between:

- Reason and passions

- The intellectual and the instinctive

- Understanding and will.

Life is a pilgrimage, a dream, and the world is a theater of appearances. His pessimism is tempered by his faith in God and by the strong rationalism he assimilated from Thomas Aquinas. The sense of anguish of many of his characters brings him closer to contemporary Christian existentialism and the pessimism of Arthur Schopenhauer:

What is life? A frenzy. What is life? An illusion, / a shadow, a fiction, / and the greatest good is small. / That all life is dream, / and dreams, dreams are!

Similarly, Fernando, the constant prince, exclaims thus shortly before dying consumed by his own will:

But what evil is not mortal / if mortal man is, / and in this confusing abyss / self disease / comes to kill him afterwards? / Man, look that you are not / neglected. The truth / follows, that there is eternity / and another disease do not wait / that I warn you, for you are / your greatest disease. / Stepping the hard/continuous land man is, / and every step he gives / is upon his tomb. / Sad law, hard sentence / is to know in any case / every step great failure! / is to go forward, / and God is not to do enough / that has not taken that step.The constant princeDay III

Calderón has a providentialist concept of history, ancient or contemporary, which is the mark of the divine will and therefore has a meaning, although God does not allow us to find it in earthly life, and contemplates that same will in the natural world, ordered according to the four elements and where one can read God's plan and promise, although not guess its ultimate meaning.

Calderón's thematic repertoire is extensive and is treated with many different variants; the honor; man's relationship with power and, in relation to this, freedom and moral responsibility or the conflict between reality and illusion, frequent in the baroque aesthetics of disappointment. It deals in a particular way with pathological jealousy and oedipal conflicts.

Culture Icon

The appreciation for his figure, started from Menéndez Pelayo, was consolidated in the XX century to the point of being considered as a cultural icon.

Two centuries after his death, some social groups would come to regard him as a defender of the Catholic faith and of the pre-liberal Spanish way of life. In 1881, during an act in El Retiro, related to the commemoration of Calderón's bicentennial, Menéndez Pelayo would toast with foreign academics for the celebration of Calderón's Spain and the superiority of the Latino race over "Germanic barbarism".

Félix Sardá y Salvany questioned the claim made by progressives and liberals of the double centenary. For the former, his figure was the most brilliant incarnation of the Spanish religious position.

Beyond this, readers, academics, performers and theater groups around the world recognize Calderón de la Barca as one of the most brilliant writers and playwrights of the Baroque period. Along with his texts, the demands raised by the Calderonian theater contributed decisively to perfecting and increasing the technological means available to the aurisecular theaters in which they were performed.

Calderón's dramatic school

Calderon's refined dramatic formula and his particular style were imitated by important geniuses who, like the one from Madrid, reworked works already composed by Lope and his disciples at the same time that they composed original pieces. The most important among these authors were Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla and Agustín Moreto, but Antonio de Solís y Rivadeneyra, Juan Bautista Diamante, Agustín de Salazar, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, Cristóbal de Monroy, Álvaro Cubillo de Aragón and Francisco Bances Candamo. Other authors who followed Calderón and achieved some success were also Juan de Zabaleta, Juan de la Hoz y Mota, Jerónimo de Cáncer, Juan de Matos Fragoso, Alejandro Arboreda and Antonio Coello, who frequently wrote in collaboration; also Juan Vélez de Guevara, son of the famous playwright Luis Vélez de Guevara; Antonio Martinez de Meneses and Francisco de Leiva.

Main works

Datatable dramatic pieces

- The confused jungle, comedy of entanglement (1622).

- Love, honor and powerhistorical comedy (1623).

- The schism of England, historical drama (1627).

- House with two doors, bad is to keep, comedy of entanglement (1629).

- The mistress, comedy of entanglement (1629).

- The constant prince, historical drama (1629).

- The band and the flower comedy (1632).

- The Supper of King Baltasar, sacramental car (1632).

- The magical wonderreligious drama (1637).

- The greatest monster in the world, drama of honor (1637).

- The doctor of your honor, drama of honor (1637).

- The two lovers of heavenreligious drama (1640).

- Secret to voice, palatine comedy (1642)

- The painter of his dishonor, drama of honor (1650).

- The mayor of Zalamea, drama of honor (1651).

- The daughter of the air, historical drama (1653).

- The Great Theatre of the Worldsacramental car (1655).

- Keep out of the water., comedy of entanglement (1657).

- Eco and Narcissus, mythological drama (1661).

- Hado and currency of Leonido and Marfisa (1680).

Drama

- Mayor of Zalamea, El.

- Beloved and hated.

- Love after death or the Tuzaní of the Alpujarra.

- Apollo and Climene.

- Secret aggrieved secret revenge.

- Weapons of beauty, Las.

- Aurora in Copacabana, La.

- Hairs of Absalom, Los.

- Demon chains, Las.

- Celos, even from the air, kill.

- Cisma de Ingalaterra, La.

- Give it all and give nothing.

- Of a punishment three revenges.

- Devotion of the Cross, La.

- Two lovers of heaven, The.

- Love and loyalty duels.

- Eco and Narcissus.

- In this life everything is true and everything is a lie (1664).

- Statue of Prometheus, La.

- Exaltation of the Cross, La.

- Fiera, the lightning and the stone, La.

- Fieras afemina amor.

- Fineness against fineness.

- Fortunes of Andromeda and Perseus.

- Gulf of sirens, El.

- Grand Cenobia, La.

- Great Prince of Fez, The.

- Air Daughter, La (two parts).

- Son of the Sun, Faeton, The.

- Sons of fortune, Theagenes and Cariclea, The.

- José de las mujeres, El.

- Judas macabeo.

- Laurel de Apolo, El.

- Luis Pérez el Gallego.

- Magical prodigious, El.

- Greatest love, El.

- Greatest monster in the world, The.

- Doctor of your honor, The or The jealous of his honor.

- Monster of gardens, El.

- No love is freed from love.

- Girl of Gómez Arias, La.

- Origin, loss and restoration of the Virgin of the Sagrarian or The three ages of Spain.

- Dessert duel de España, El.

- Paintor of his dishonor, El.

- Constant Prince, El.

- Purgatory of Saint Patrick, El.

- Purple of the rose, La.

- Knowledge of evil and good.

- Second Scipio, El.

- Sibila de Oriente, La.

- Breda Site, El.

- Three affections of love, The.

- Three justices in one, Las.

- Three major prodigies, The.

Comedies

- And the mistake, The.

- Hate and love effects.

- To thank and not to love.

- Mayor of himself, The.

- Friend, lover and loyal.

- Love, honor and power.

- Before everything is my lady.

- Argenis and Poliarco.

- Definite astrologer, The.

- Auristela and Lisidante.

- Band and flower, La.

- Shut up..

- Well, come on, bad, if you come alone.

- Each for himself.

- House with two doors, bad is to keep.

- Castle of Lindabridis, El.

- Count Lucanor, El.

- With whom I come, I come.

- What is greater perfection.

- Lady leprechaun, La.

- Give time to time.

- Wise voice, La.

- Of one cause, two effects.

- Such and misleading of the name.

- Empeños de un acaso, Los.

- Charm without charm, El.

- Hidden and covered, El.

- Fire of God is to want well.

- Ghost Galan, The.

- Keep out of the water..

- Gusts and disgusts are no more than imagination.

- Hado and currency of Leonido and Marfisa.

- Poor man all traces.

- Falerina Garden, El.

- Lances of love and fortune.

- Master of Dance, The.

- White hands don't offend, Las.

- Tomorrow will be another day.

- Mornings in April and May.

- It's better she was.

- Woman, cry and beat.

- Nobody trusts your secret..

- There is no mockery with love.

- There's nothing like silence.

- Not always the worst is true.

- To beat love, to want to beat him.

- Worse it was..

- First it's me..

- Bridge of Mantible, La.

- Voice secret, The.

- Confusing jungle, La.

- Lady and maid, La.

- There's also mourning in the ladies..

Sacramental Cars

(In alphabetical order)

- To God for state reason (1650-1660).

- Man's food, the (1676).

- To Mary the heart (1664).

- Love and be loved and divine Filotea (1681).

- Andromeda and Perseo (1680).

- Holy Year of Rome, The (1650).

- Holy Year in Madrid, El (1615–1652).

- Tree of the best fruit, The (1661).

- Ark of God captive, The (1673).

- Supper of King Baltasar, La (1634).

- Lamb of Isaiah, The (1681).

- Almudena Cube, El (1651).

- Cure and disease, La (1657-1658).

- Devotion of Mass, La 1637?

- Mute devil, The (1660).

- Day greater, El (1678).

- Divine Jason, The (before 1630).

- Divine Orpheus, The (two versions).

- Guilt charms, Los 1645?

- Ruth's ears, Las (1663).

- Grand Duke of Gandy, The 1639?

- Great Market of the World, The (1634-1635).

- Great theater of the world, The (1634-1635).

- Hidalga del Valle, La 1634?

- Humility crowned of plants, La (1644).

- Sitiada Church, La (before 1630).

- General pardon, El (1680).

- Immunity of the Sacred, La (1664).

- Falerina Garden, El (1675).

- Labyrinth of the world, El (1677).

- Leprosy of Constantine, La.

- Lirio y la azucena, El (1660).

- Called and chosen 1648-1649?

- What goes from man to God 1640?

- Master of the Toison, El (1659).

- Mysteries of the Mass, The (1640).

- Mystic and real Babylon (1662).

- Ship of the merchant, La (1674).

- There is no instant without miracle (1672).

- There is no more fortune than God 1653?

- New hospice of the poor (1688).

- New Retreat Palace, El (1634).

- Order of Melchisedech, El.

- Military orders, Las (1662).

- Pastor Fido, El 1677?

- Piel de Gedeón, La.

- Paintor of his dishonor, El.

- Marriage Pledge of the Body and the Soul, The (1634).

- First flower of Carmel, La (before 1650).

- First and second Isaac (before 1659?)

- First man's shelter and tasteful pool, El (1661).

- Protest of Faith, La (1656).

- Psiquis and Cupid (1640).

- Who's gonna find a strong woman?.

- Redemption of captives, La (about 1672).

- Sacro Parnaso, El (1659).

- Holy King Don Fernando, El (first and second part) [1671].

- Second wife and triumph dying, La 1648-1649?

- Seed and tarp, La (1651).

- Metal Snake, La (1676).

- Siembra of the Lord, La (before 1655).

- General relief, El (1644).

- Dreams are true (1670).

- Hidden Treasure, The (1679).

- Tower of Babylon, La.

- Your neighbor as you (second wording) [before 1674].

- Universal redemption, La. Your neighbor as you.

- General Vacant, La (1649).

- Valle de la Zarzuela, El (about 1655?)

- Poison and triaca, El (1634).

- True God Pan, The (1670).

- Old lamb, El (1665).

- Life is dream, The (second wording) [before 1674].

- Lord's vineyard, La (1674).

Brief theater (dances, hors d'oeuvres, jácaras and mojigangas)

- Dance of the faces (part 2).

- Baile de la plazuela de Santa Cruz.

- Baile de los zagales.

- Entremés de la barbuda (parts 1 and 2).

- Entremés de la casa de los linajes.

- Messengers.

- Entremés de la casa holgana.

- Between the guest.

- Entremés de los degollados.

- Entremés de don Pegote.

- Entremés del dragoncillo.

- Between the school and the soldier.

- Entremés de la Franchota.

- You keep my back..

- Training of the instruments.

- Entremés de las jácaras (part 1).

- Entremés del Challenge de Juan Rana.

- Means of the melancholic.

- Messenger.

- Entremés del mayorazgo.

- Entremés de la plazuela de Santa Cruz.

- Entremés de la premática (parts 1 and 2).

- Mess of the clock and geniuses of sale.

- Entremés de la rabia (part 1).

- Entremés del robo de las Sabinas.

- Entremés del sacristán mujer.

- Messenger.

- Entremés of the triumph of Juan Rana.

- Mellado's face.

- Mojiganga de la garapiña.

- Mojiganga de los guisados.

- Mojiganga of the blind.

- Mojiganga of death.

- Mojiganga de la pandera.

- Mojiganga del Parnaso (part 2 of Rabies).

- Mojiganga of the widow's condolences.

- Juan Rana Mojiganga in the zarzuela.

- Mojiganga of the Recreational Sites of the King.

Collaborative works

- The barbarian of the mountains (the first day of Tomé de Miranda, the other two of Calderón).

- Beautiful Margarita, La (with John of Zebaleta and Jerome of Cancer and Velasco).

- More hydalga beauty, La (with Juan de Zabaleta and Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla).

- Monster of Fortune, The (with Juan Pérez de Montalbán and Francisco de Rojas Zorrilla).

- Prodigy of Germany, The (with Antonio Coello and Ochoa).

- Proceedings of Frislan, and death of the King of Sweden, Las (with Antonio Coello and Ochoa).

- Husbanded Troy (with Juan de Zabaleta).

- Yerros of nature and fortunes (with Antonio Coello and Ochoa).

Attributed Works

- Punishment in betrayal, El.

- First blazon of Austria, El.

- Looking for the mojiganga, El.

- Saco de Antwerp, El.

- Satisfied grievances and Sicilian eves, Los.

- Word in the woman, The.

- Women when they want, Las.

- Honest, confusion and love.

- Running over the honor.

- Married, El

- Best witness is God, The.

- The Prodigy of Germany.

- Patience of Job, The.

- Ask with a bad try, El.

- Sorry to punish more, El.

- Marco Antonio and Cleopatra.

Historical editions of works by Calderón

- First part of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Madrid, for the widow of Juan Sánchez, at the expense of Gabriel de León, 1636

- Second part of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Madrid, By María de Quiñónez, 1637 (Second part of comedies of the famous poet Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca [...], that nueumente correctgida publica don Juan de Vera Tassis and Villaroel [chuckles]sic], in Madrid, by Francisco Sanz, 1683)

- Third part of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Madrid, by Domingo García Morràs, on the coast of Domingo Palacio and Villegas, 1664

- Part IV of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Madrid, by Bernardo de Hervada, at the expense of Antonio de la Fuente, 1674

- True Fifth part of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca published by Don Juan de Vera Tassis and Villarroel, Madrid, Por Francisco Sanz, 1682

- Sixth part of Comedias by Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca, which is re-corrected by its original publics don Juan de Vera Tassis and Villarroel, Madrid, by Francisco Sanz, 1683

- Séptima parte de Comedias de Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca que nuevo correctgidas, publica Don Juan de Vera Tassis y Villarroel, Madrid, Por Francisco Sanz, 1683

- 8th part of comedies of the celebrated Spanish poet Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca [...], which corrected by its original publics don Iuan de Vera Tassis and Villarroelin Madrid, by Francisco Sanz, 1684

- Ninth part of Comedias de Don Pedro Calderon de la Barca, published by Don Juan de Vera Tassis and Villarroel, Madrid, Por Francisco Sanz, 1691

- Ed. facs. of the nine parts in The comedias of Calderón. A facsimile editionD. W. Cruickshank and John E. Varey, London, 1973, 19 vols.

- The Comedias de ~, with the best editions so far published, corrected and given to light by Juan Jorge Keil, Leipsique, published in Ernesto Fleischer's house, 1827-1830, 4 vols.

- Comedias de Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca: collection more complete than all previous ones made and illustrated by Juan Eugenio Hartzenbusch, Madrid, M. Rivadeneyra, 1848-1850, 4 vols. Library of Spanish Authors, 7, 9, 12, 14

- sacramental, allegorical, and historians of Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, Posthumous Works, which brings forth Don Pedro de Pando y Mier, Part One, Madrid, En la Imprenta de Manuel Ruiz de Murga, 1717, 6 ts. (ed. Allegorical sacramental cars and historians of the phenix of the poets / the Spanish, Don Pedro Calderón de la Barca, cavallero of the Order of Santiago, chaplain of honor of S. M. and of the Lords New Kings of the Holy Church of Toledo; Posthumous works that bring forth Don Juan Fernández de Apontes, Madrid, at the office of the widow of Don Manuel Fernández and Printer of the Supreme Council of Inquisition, 1759-1760, 6 vols.

- Ignacio Arellano (dir.), Complete Sacramental Cars of CalderónPamplona-Kassel, University of Navarra-Edition Reichenberger, 1992-2009)

- Entremes, hulls and mojigangased. de E. Rodríguez y A. Tordera, Madrid, Castalia, 1983 (reeds. 1990, 2001)

- Short comic theatreed. de M.a L. Lobato, Kassel, Reichenberger, 1989

- Complete works, ed., prol. and notes by Ángel Valbuena Briones, Madrid, Aguilar, 1952-1956, 3 vols. (t. 1. Dramas, t. 2. Comedies, t. 3. Sacramental cars, compilation., prol. and notes by Angel Valbuena Prat)

- Sacramental carsed. by Enrique Rull Fernández, Madrid, Biblioteca Castro, 8 vols., printed 3 since 1994.

- Comediased. coordinated by Luis Iglesias Feijoo, Madrid, Biblioteca Castro, 6 vols. since 2007.

Creative works inspired by Calderonian arguments

- Antoine Le Métel d'Ouville, L'Esprit follet (Paris, 1642), imitation of The mistress.

- Antoine Le Métel d'Ouville, Jodelet astrologue (Paris, 1646), imitation of The fake astrologer Calderon.

- Thomas Corneille imitates The fake astrologer Calderon in his piece Le Feint Astrologue (1647, printed in Ruan and Paris, 1651), and also imitated by John Dryden in his An Evening's Love the following year.

- François Le Métel de Boisrobert imita House with two bad doors is to keep in L'Inconnue (Paris, 1655)

- Philippe Quinault imita The ghost gallant in his Le Fantôme amoureux (1657)

- François Le Métel de Boisrobert imita Life is sleep in his novel La vie n'est qu'un songe (1657)

- Thomas Corneille imitates House with two bad doors is to keep and The endeavors of a in Les engagéments du hazard (Ruan and Paris, 1657)

- George Digby adapts Not always the worst is true in his work Elvira, or the Worst not Always True (1664)

- John Dryden inspires his The Indian Emperour (1665) in The constant prince.

- Music for Secret to voice (1671) by Giovanni Maria Pagliardi.

- William Wycherley inspires his Love in a Wood (1671) in Mornings in April and May Calderon.

- William Wycherley inspires his The Gentleman Dancing-Master (1672) in The Master of Dancer Calderon.

- John Dryden inspires his The Assignation (1672) in With whom I come, I come Calderon.

- Aphra Behn inspires her The Young King (1679) in Life is sleep Calderon.

- Alain René Lesage imitates Worse it was. of Calderon in his comedy Don César Ursinrepresented in 1707 in Paris successfully.

- Il y a bonne justice, ou le Paysan magistrat (1778), comedy of Jean-Marie Collot d'Herbois inspired by The mayor of Zalamea.

- Isabelle et Fernand ou L'Alcalde de Zalaméa (1783), comédie mêlée d'ariettes de Stanislas Champein, con libreto de L. - F. Faur sobre The mayor of Zalamea.

- The mayor reelected [Teatro de la Cruz, December 25, 1792], tonadilla general de Blas de Laserna.

- The tragedy [1799-1808], tonadilla to duo of unknown author.

- In 1814 published Nicolás Böhl de Faber The Gaditano Mercury an article entitled “Schlegel’s reflections on the German-translated theatre” where Calderon’s work is claimed by introducing Romanticism in Spain.

- The poet Percy B. Shelley wrote in November 1820 a letter to Thomas L. Peacock where he says "I read no more than Greek and Spanish: Plato and Calderón are my gods."

- Der Graf Lucanor (1845), translation of Count Lucanor by Joseph von Eichendorff.

- Die geistlichen Schauspiele Calderons (1846–53), 2 vols., by Joseph von Eichendorff.

- Calderon, his Life and Genius, with Specimens of his Plays (1856), essay and anthology of Irish Richard Chenevix Trench.

- Incidental music Der wundertätige Magus (The magical wonder), 1865, by Josef Gabriel Rheinberger.

- Incidental music Der Richter von Zalamea (1883) by Engelbert Humperdinck.

- The Humours of the Court (1893), a comedy of Robert Bridges inspired by Secret to voice Calderon.

- Two songs Der Richter von Zalamea (1904), with music by Richard Strauss, with the translation of Rudolf Presber.

- Manuel de Falla, incidental music for the representation of the sacramental car of Pedro Calderón de la Barca The Great Theatre of the World which was held in the Plaza de los Aljibes of the Alhambra on June 27, 1927.

- Laurenca, JohannisnachtScenic music for Carl Schadewitz (1887-1947).

- The poet Boris Pasternak decided in his last years to translate the work of Pedro Calderón de la Barca.

- Le théâtre du monde (1956), opera by Heinrich Sutersmeister, with libretto by Edmond Jeanneret, about The Great Theatre of the World.

- Calderón (1966), theatrical piece by Pier Paolo Pasolini, is inspired by Life is sleep, and was taken to the television for the RAI in 1981 on the version of the stable theatre of Friuli-Venezia Giulia, by Giorgio Pressburger. The work had already been represented by Luca Ronconi.

- Francisco Nieva makes the figurines for The mistress in 1966.

- The famous assembly The constant prince performed by Polish stage director Jerzy Grotowski in Breslavia in 1968, with interpretation of Ryzsard Cieslak, influenced his dramatic conception of poor theatre.

- Mahmud Ali Makki translates to Arabic The mayor of Zalamea de Calderón de la Barca (1993).

- Incidental music The Great Theatre of the World (1998) by Antón García Abril.

- Calderon is a character in the novel The Sun of Breda (1998) of Arturo Pérez-Reverte

- The novel by Giannina Braschi United States of America (2011) inspired Life is sleep.

- Albert Camus made an adaptation The Devotion of the Cross to French, published by Gallimard.

Operas based on works by Calderón de la Barca

Hate and love affections

- Gare dell ́Odio e dell ́Amore, opera scenica, composer unknown, Macerata, 1666;

- L ́odio e l ́amore, music by C. F. Pollaroli, Teatro S. Giovanni Grisostomo, Venice 1703 / 1717;

The mayor of himself

- Sein Selbst Gefangener, oder der närrische Prinz Jodelet, opera buffa, music by Johann Wolgang Franck, Hamburg 1680;

- Il carceriere di se medesimo, opera with music by Alessandro Melani, Florence 1681;

- Der lächerliche Printz Jodelet, opera with music by Reinhard Keiser, Hamburg 1726;

The mayor of Zalamea

- Isabelle et Fernand, ou l ́Alcade [sic] de ZalameaOpéra comique de N. Faur, Paris 1784;

- Pedro de Zalameaopera with music by Benjamin Godard, Antwerp 1884;

- Dommeren i Zalamea, opera by Christian Frederik Emil Horneman, 1892;

- Der Richter von Zalamea, opera with music by Georg Jarno and libretto by Viktor Blüthgen and music by Georg Jarno, 1899;

- Pedro Crespo oder der Richter von Zalamea, opera with music by Arthur Piechler, 1944;

- The mayor of Zalamea, zarzuela with music by Henri Collet, 1946.

Friend, lover and loyal

- La potenza della lealtá, riverena e fedeltá, opera with music of unknown author, Bologna 1685;

Not even love is free from love

- No love is freed from love, semi-opera with libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalg, 1662;

- Psiche or vero Amore innamorato, opera with libretto by Giuseppe Domenico de Totis and music by Alessandro Scarlatti, (1683);

The band and the flower

- Liebe und Eifersucht, opera with libretto and music by E.T.A. Hoffmann, 1807;

A house with two doors is bad to keep

- La maison a deux portes, opera comique, composer unknown, Foire de Saint-Laurent 1755;

- Hus med dubbel ingång (1970), lyric comedy with music by Hilding Constantin Rosenberg, 1970;

Cephalus and Pocris

- Procris und Cephalus, operas with music by Georg Bronner, Hamburg 1701;

Jealousy even of the air kills

- Celsius even of the air kill (1660), libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalgo, Madrid 1660;

Against love disappointment

- Against deceitful love, semi-opera with libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalgo, 1679;

The Goblin Lady

- The Lady and the Devil, operatic gift of William Dimond and music by Michael Kelly, London 1820

- Give me Kobold, opera with libretto by Paul Reber and music by Joseph Joachim Raff, Berlin and Weimar 1870;

- Die Dame Kobold, opera with Carl Scheidemantel libretto using the music Cosi fan tutte by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Leipzig 1909.

- Give me Kobold, opera with music and libretto by Felix Weingartner; Vienna 1916;

- Give me Kobold, opera with libretto by E. Kurt Fischer and music by Kurt von Wolfurt, Kassel 1940;

- Give me Kobold, musical comedy of Gerhard Wimberger based on the translation of Hugo von Hofmannsthal, 1964;

The divine Orpheus

- The Divine Orpheus (1984), opera with libretto by Sumiko Shibata and music by Minao Shibata, 1984;

Echo and Narcissus

- Echo und Narcissus, opera with Friedrich Christian Bressand libretto and music by Georg Bronner, Hamburg 1694;

The efforts of a chance

- Le armi e gli amori, opera with libretto by Giulio Rospigliosi and Marco Marazzoli music, Florence 1658;

The charms of guilt

- Der Sünde Zauberei (1929), opera with libretto based on the translation of Joseph von Eichendorff and music by Walter Courvoisier, 1929;

The statue of Prometheus

- The statue of Prometheus, semi-opera with libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalgo, 1670;

Beasts feminize love

- Fieras afemina amor, (1724), opera with libretto by Alejandro Rodríguez and music by Giacomo Facco, 1724

The fortunes of Andromeda and Perseus

- Andromeda and Perseus fortunes, semi-operates with music of unknown composer, probably Juan Hidalgo, conserved at the Houghton Library, Harvard, Madrid 1653;

The ghost gallant

- Der Liebhaber nach dem Tode, opera with C. W. Salice-Contessa libretto and E.T.A. music. Hoffmann, Leipzig 1826, the work is lost;

Fate and badge of Leonido and Marfisa

Fate and currency by Leonido and Marfisa, semi-opera with a libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalgo, 1680;

The daughter of the air

- Semiramide ossia schiava fortuneta, opera with libretto by G. A. Moniglia and music by Marc ́Antonio Cesti, Vienna 1667;

- Die glückliche Sklavin oder die Ähnlichkeit der Semiramis un des Ninus, opera with unknown author libretto and music by Marc ́Antonio Cesti, Hamburg 1693;

- Semiramis, melodrama with libretto of the Baron Otto von Gemmingen and music by Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, 1779 (text and music are lost);

- Die Tochter der Luft, opera with libretto by Josef Schreyvogel and music by Josef Weigl, 1819;

- Semiramis, fragment of a libretto written by Hugo von Hofmannsthal to be placed in music metro by Richard Strauss

The son of the sun, Phaethon

- The Son of the Sun, Faeton, semi-opera with libretto by Pedro Calderón de la Barca and music by Juan Hidalgo, 1675;

Hauls of love and fortune

- Le Vicende d'Amore e di fortuna, opera with libretto by G. B. Toschi and music by unknown author, Modena 1677;

- Vicende d ́amore e di fortuna, opera with libretto by C. Pallavicino and several composers, Venice 1710;

- Tiberius, imperatore d'Oriente, opera with the same libretto by C. Pallavicino and music by Gasparini, Venice 1702;

The Wonderful Magician

- Il mago, unfinished opera with libretto by Emilio Mucci and music by Licinio Recife;

White hands do not offend

- White hands don't offend opera by José de Herrando, 1761;

The greatest love charm

- Ulysses und Circe, Singspiel with libretto based on the translation made by August Wilhelm Schlegel and music by Bernhard Romberg, Berlin 1807;

- Circe, opera with libretto based on the translation by August Wilhelm Schlegel and music by Werner Egk, München 1950;

The biggest monster in the world

- Le Mariene ovvero, il maggior showro del mondo, opera with libretto by Giacinto Andrea Cicognini and music by unknown composer, Perugia 1656;

- Gli eccessi della gelosia, opera with Domenico Lalli libretto and music by Tomaso Albinoni, Venice 1722

- The greatest monster jealousy, opera by Josep Soler i Sardà, 1977;

The Monster of the Gardens

- Achille in Sciro, opera with libretto by Pietro Metastasio and music by Antonio Caldara, Vienna 1736;

- Achille in Sciro, melodrama with libretto by Pietro Metastasio and music by Niccola Jomelli, Vienna 1749;

It's worse than it was

- Dal male il bene, dramma per musica con libreto de Giulio Rospigliosi y música de Antonio Maria Abbatini (acto primer y terceros) y Marco Marazzoli (acto segundo), 1656

The Mantible Bridge

- Fierabras, opera with libretto by Joseph Kupelwieser based on the translation of August Wilhelm Schlegel and music by Franz Schubert, Leipzig 1886

The purple of the rose

- The Purple of the Rose, opera with Calderón de la Barca libretto and music by Tomás de Torrejón and Velasco and Lima 1701.

The open secret

- Das laute GeheimnissAllgeyer's libretto based on the recast made by Carlo Gozzi, planned to be put on musician metro by Johannes Brahms, Hamburg 1869 / 1872;

The site of Breda

- Friedenstag, opera with libretto by Joseph Gregor and music by Richard Strauss, 1938;

Life is a dream

- Der königliche Printz aus Bohlen Sigismundus, oder das menschliche Leben wie ein Traum, Christian HEinrich Postel script based on the Schouwenbergh version and music by J. G. Conradi, Hamburg 1693

- The vie is a songe, opera with libretto by Louis Fuzelier and music by unknown composer, Paris 1717;

- Segismondo, re di Poland, opera with unknown author libretto and music by Leonardo Vinci, Turin 1727;

- Sigism, opera with libretto by Giuseppe Foppa, probably based on the Boissy recast with music by Gioachino Rossini, Venice 1814;

- Das Leben ein Traum, opera with music by Friedrich Ludwig Seidel, 1818;

- Das Leben ein Traum, oder das Horoskop, opera with libretto by A. Steppes and music by Louis Schlösser, Darmstadt 1839;

- The vita e sogno, opera with libretto and music by Gian Francesco Malipiero, Breslau 1943;

- Life is a Dream, opera with James Maraniss libretto and music by Lewis Spratlan, 1980

- Aldimiro overo, Favor per favore (1683) operas and music by Alessandro Scarlatti and libretto by Giuseppe Domenico de Totis

Contenido relacionado

Karen Blixen

J.K. Rowling

Hamelin's futist