Paul of Tarsus

Paul of Tarsus, with the Jewish name Saul of Tarsus or Saul Paul, and better known as Saint Paul (Tarsus, Cilicia AD 5-10-Rome, 58-67), is called the "Apostle to the Gentiles", the "Apostle to the nations", or simply "the Apostle". Founder of Christian communities, evangelizer in several of the most important urban centers of the Roman Empire such as Antioch, Corinth, Ephesus, and Rome, and redactor of some of the earliest Christian canonical writings—including the oldest known, the First Epistle to the Thessalonians —, Paul constitutes a personality of the first order of primitive Christianity, and one of the most influential figures in the entire history of Christianity.

From the analysis of his authentic epistles, it emerges that Paul of Tarsus gathered in his personality his Jewish roots, the great influence that Hellenic culture had on him and his recognized interaction with the Roman Empire, whose citizenship —according to the book of the Acts of the Apostles—exercised. Paul used this set of conditions to found several of the first Christian centers and to announce the figure of Jesus Christ to both Jews and Gentiles. Without having belonged to the initial circle of the Twelve Apostles, and following paths marked by misunderstandings and adversities, Paul became an eminent architect in the construction and expansion of Christianity in the Roman Empire, thanks to his talent, his conviction and his character. indisputably missionary. His thought shaped the so-called Pauline Christianity, one of the four basic currents of primitive Christianity that ended up integrating the biblical canon.

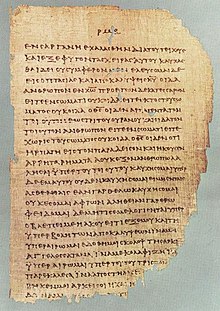

From the so-called Pauline Epistles, the Epistle to the Romans, the First and Second Epistle to the Corinthians, the Epistle to the Galatians, the Epistle to the Philippians, the First Epistle to the Thessalonians and the Epistle to Philemon have in Paul of Tarsus their practically indisputed author. They are, together with the book of the Acts of the Apostles, the independent primary sources whose exhaustive scientific-literary study allowed to set some dates of his life, establish a relatively accurate chronology of his activity, and a fairly finished semblance of his passionate personality. His writings, of those who have reached the present time copies as old as the Daddy P{displaystyle {mathfrak {P}}}}46 dated from the years 175-225, they were unanimously accepted by all Christian Churches. His figure, associated with the summit of the Christian experimental mystique, was inspiring in arts as diverse as architecture, sculpture, painting, literature, and cinematography and is for Christianity, already since its early days, an inescapable source of doctrine and spirituality.

Name

Paul did not change his name upon embracing faith in Jesus Christ as Messiah of Israel and Savior of the Gentiles, since, like all Romans of the time, he had a praenomen related to a family characteristic (Saul, his Jewish name, which etymologically means 'invoked', 'called'), and a cognomen, the only one used in his epistles (Paulus, his Roman name, which etymologically it means 'small' or 'little').

The Apostle called himself Παῦλος (Paulos) in his letters written in Koine Greek. This name also appears in the Second Epistle of Peter 3:15 and in the Acts of the Apostles from 13, 9.

Before that verse, the Book of Acts calls him with the Greek form Σαούλ (Saoul) or Σαῦλος (Sauls) (Hebrew שָׁאוּל; Modern Hebrew Sha'ul, and Hebrew Tiberian Šāʼûl). The name, expressed in ancient Hebrew, would be equivalent to that of the first king of Ancient Israel, a Benjaminite like Paul. That name means "invoked", "called" or "requested" (of God or Yahveh).

His name Σαῦλος (Saulos) is also used in accounts of his "conversion". The Acts of the Apostles further notes the passing of " Saul" to "Paul", when using the expression "Σαυλος, ο και Παυλος", "Saul, also [called] Paul" or "Saul, [known] also [by] Paul", which does not mean a name change. In Hellenistic Judaism, it was relatively common to bear a double name: one Greek and one Hebrew.

The name Paulos is the Greek form of the well-known Roman cognomen Paulus, used by the gens Emilia. How Paul got this Roman name can only be conjectured. It is possible that he was related to the Roman citizenship that his family possessed for living in Tarsus. It is also possible that some ancestor of Paul adopted that name because it was that of a Roman who manumitted him. Although paulus means 'small' or 'meager' in Latin, it is not related to his physical build or his character.

However, Paul was able to give another meaning to the use of the name Paulos. Giorgio Agamben remembers that when a slave-owning Roman lord bought a new servant, he would change his name as a sign of his change of status or situation. Agamben points to examples of this: «Januarius qui et Asellus (Donkey); Lucius qui et Porcellus (Suckling Pig); Ildebrandus qui et Pecora (Cattle); Manlius qui et Longus (Long); Aemilia Maura qui et Minima (A minor)". The person's name appeared first; the new name was indicated at the end; both names were joined by the formula "qüi et", which means 'which is also [called]'. In the book of the Acts of the Apostles the phrase appears: "Σαυλος, ο και Παυλος" ('Saul, also [called] Paul'), where "ο και" is the Greek equivalent of the Latin expression "qüi et". Agamben proposes that Saul changed his name to Paul when he changed status, from free to servant/slave, since he considered himself a servant of God or his Messiah. Following this line of thought, Paul would have considered himself a small human instrument. (paulus, 'small'; Saint Augustine of Hippo points out the same thing in Comm. in Psalm. 72,4: «Paulum […] minimum est» ), of little value, chosen, however, by God, his Lord, to carry out a mission.

Fonts

Pablo de Tarso is known mainly for two types of documentation, which can be classified according to their level of importance:

- Your authentic letters. Probably written all in the 1950s, are the following (in a possible chronological order): First Epistle to the Thessalonians, First Epistle to the Corinthians, Epistle to the Galatians, Epistle to Philemon, Epistle to the Philippians, Second Epistle to the Corinthians and Epistle to the Romans. They are considered the most useful and interesting source, for the simple reason that they come from him and, consequently, are the most faithful reflection of his human, literary and theological personality.

- The Acts of the Apostles. Particularly from chapter 13 are, for practical purposes, the facts made by Paul. The Acts convey a remarkable amount of information about him, from his "conversion" on the way to Damascus until his arrival in Rome as a prisoner. Traditionally attributed to Luke the Evangelist, historiographic valuation is nevertheless controversial. The general biographical picture that shows the book of Acts is not questioned, but when confronting this writing closely with authentic letters, there are certain nuances or absences in the field of events (by citing two examples, the Acts do not at all mention Paul's tormentful relations with the Church of Corinth; Paul's authentic letters do not imply the existence of the so-called "apostolic decree" in a given Acts 15,). There are also theological discordances (for example, Acts overlook the typically Pauline posture of justification of faith without the works of the law, well marked for example in the Epistle to the Romans). However, Victor M. Fernández notes the existence of certain passages of the Acts of the Apostles that mark the particular style of Christianity that Paul preached: the Gospel of the grace of God, that would equal the accent that Paul put on justification by grace and not for the works of the Law.

- In the case of contrast on common themes, preference is usually given to authentic Pauline letters; on the other hand, those data from the book of Acts that are not discordant with the letters are accepted.

There is another type of works, the so-called “pseudoepigráficas or deuteropauline epistles”, which were written under the name of Paul, perhaps by some of his disciples after his death. They include the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians, the Epistle to the Colossians, the Epistle to the Ephesians, and three "pastoral letters," the First and Second Epistles to Timothy, and the Epistle to Titus. Since the 19th century, different authors have denied direct Pauline authorship of these letters, attributing them to various figures of later disciples. However, other authors maintain the Pauline authorship of these letters, particularly Colossians, arguing that the variations in style and theme can be justified by the change in the historical framework in which they were written. (See section on the epistles pseudepigraphical).

Biography

Birth of Paul

Saul Paul was born between the years 5 and 10 in Tarsus (in present-day Turkey), then the capital city of the Roman province of Cilicia, on the southern coast of Asia Minor.

Date

In the Epistle to Philemon, he declared himself an old man (presbytés). He wrote it while in prison, either in the mid-50s in Ephesus, or in the early 1950s. of the year 60 in Rome or Caesarea. It is assumed that at that time old age was reached around fifty or sixty years. Based on this data, it is estimated that Paul was born at the beginning of the first century, around the year 10. Therefore, he was a contemporary of Jesus of Nazareth.

Place

Luke affirms that Paul was a native of Tarsus, a city located in the province of Cilicia, information considered credible. This tradition corroborates that Paul's mother tongue was Greek from his birth, and that no semitisms are observed in his use of this language.

In addition, Paul used the Septuagint, a Greek translation of Biblical texts, used by Jewish communities in the ancient world beyond Judea. This set fits the profile of a Diaspora Jew born in a Hellenistic city. Added to this is the non-existence of alternative traditions that mention other possible places of birth, with the exception of a late notice by Jerónimo de Estridón that records the rumor that Pablo's family came from Giscala, a city of Galilee ( De viris illustribus 5 —Commentary on Philemon—; end of the century IV), news generally considered lacking in backup.

By then, Tarsus was a prosperous city of some importance (Acts 21, 39). Capital of the Roman province of Cilicia since 64 BC. C., was located at the foot of the Taurus Mountains and on the banks of the Cidno River, whose mouth in the Mediterranean Sea served Tarsus as a port. Tarsus was commercially important, as it was part of the route linking Syria and Anatolia. It was also the center of a school of Stoic philosophy. It was thus a city known as a center of culture, philosophy, and education. The city of Tarsus was granted Roman citizenship by birth. As explained above, this situation is a possible explanation for Paul being a Roman citizen despite being the son of Jews.

Roman citizenship

The information about Paul's Roman citizenship is only presented by the Acts of the Apostles, and there are no parallels in Paul's letters, which is still a matter of debate today. Against this news, Vidal García argues that a Roman citizen would not have been beaten, as Pablo assures that it happened to him in 2 Corinthians 11, 24-25, since it was forbidden. In favor, Bornkamm points out that the name Paulus was a Roman. And if he had not been a Roman, Paul would not have been transferred to Rome after his arrest in Jerusalem. However, there are exceptions to both assumptions. Peter van Minnen, papyrologist and document researcher Greeks of the Hellenistic and Roman periods, including those of early Christianity, strongly defended the historicity of Paul's Roman citizenship, holding that Paul was a descendant of one or more freedmen, from whom he would have inherited citizenship.

Early Years, Education, and Life Status

A son of Hebrews and a descendant of the tribe of Benjamin, the book of the Acts of the Apostles also points out three other points regarding Paul: that he was educated in Jerusalem; that he was educated at the feet of the famous Rabbi Gamaliel, and that he was a Pharisee.

Education, “at the feet of Gamaliel”

Pablo's upbringing is the subject of much speculation. The majority opinion of specialists indicates that he received his initial education in the city of Tarsus itself. It is also suggested that he would have moved to Jerusalem later, as a teenager, or already a young man. Some scholars, who maintain an attitude of great reservation regarding the information provided by the Acts, they object to this data. Others do not find sufficient reason to discard the data from the book of Acts 22, 3 referring to his education at the feet of Gamaliel I the Elder, an authority of mind open. According to Du Toi, Acts and the authentic Pauline letters support it as more likely that Paul went to Jerusalem in his teenage years. More importantly, this scholar notes that the Tarsus–Jerusalem dichotomy should be overcome by recognizing that Paul's person was a meeting point and integration of a variety of influences. Paul's upbringing at the feet of Gamaliel suggests his preparation to be a rabbi.

Pharisee

That Paul was a Pharisee is a fact that came to us from the autobiographical passage of the Epistle to the Philippians:

Circumcised on the eighth day; of the lineage of Israel; of the tribe of Benjamin; Hebrew and son of Hebrews; as for the Law, Pharisee; as for zeal, persecutor of the Church; as for the righteousness of the Law, intachable.Epistle to Philippians 3, 5-6

However, these verses are part of a fragment of the letter that some authors consider to be an independent writing after the year 70. Hyam Maccoby disputed that Paul was a Pharisee, stating that there is no rabbinical trait in the letters paulinas.

However, the Pharisee character of Saul Paul in his youth is usually accepted without reluctance by other authors, to which are added the words put into the Apostle's mouth by the book of Acts:

All the Jews know my life from my youth, since I was in the bosom of my nation, in Jerusalem. They know me long ago and if they want to testify that I have lived as a Pharisee according to the strictest sect of our religion.Acts of the Apostles 26, 4-5

In summary, Saul Paul would be a Jew of deep convictions, a strict follower of the Mosaic Law.

Marital status

A topic discussed in the investigation of the "historical Pablo" is his marital status, of which there is no clear record. The texts of 1 Corinthians 7, 8 and 1 Corinthians 9, 5 suggest that, when he wrote that letter in the first half of the 50s, he was not married, but this does not clarify whether he had never been married, whether he had been divorced or if he had been widowed.

In general, researchers tend to take two majority positions:

- that he would have remained celibate throughout his life without making clear the precise reason, which would not necessarily be of a religious nature;

- I would have been married, and then I would have been widowed. This position was raised by Joachim Jeremias, and found among other followers J.M. Ford, E. Arens and, today, S. Légasse. This position assumes that Paul was married because he was preceptive in the case of rabbis. Therefore, when Paul wrote in 1 Corinthians 7, 8: "I say to the unmarried and widowed, 'it is good that they remain as I am,'" he could be classified among the widowers.chérais), not among singles (agamois); Paul would not have married again (cf. 1 Corinthians 9:5). E. Fascher, who defended Paul's perpetual celibacy, showed objections to this theory.

Romano Penna and Rinaldo Fabris point out another possible position: that Pablo and his presumed wife had separated. This assumption could be linked to the so-called Pauline privilege established by the Apostle, which consists of the right that the Christian party has to break the marriage bond when the other party is unfaithful and does not agree to live with her peacefully.

Saul Paul, persecutor

Knowledge of Jesus of Nazareth

It is worth considering whether, having been Saul Paul in Jerusalem "at the feet of Gamaliel", he personally met Jesus of Nazareth during his ministry or at the time of his death. The scholars' positions are diverse, but in general it is presumed that he was not like that, since there is no mention of it in his epistles. It is reasonable to think that, if such an encounter had happened, Paul would have recorded it at some point in writing.

This being the case, one might also question the continuing presence of Saul Paul in Jerusalem in his teenage years or youth. Starting with Acts 26, 4-5, Raymond E. Brown suggests that Saul Paul was a Pharisee from his youth. Given that the presence of Pharisee teachers outside of Palestine would be infrequent and that, in addition to Greek, Paul knew Hebrew, Aramaic, or both, the sum of all this information gives rise to the belief that at the beginning of the 30s, Saul Paul he moved to Jerusalem in order to study Torah more deeply.

The first chase

According to the Acts of the Apostles, the first reliable contact with the followers of Jesus was in Jerusalem, with the Hellenistic-Jewish group of Stephen and his companions. Saul Paul approved the stoning of Stephen the protomartyr, an execution dated from the first half of the decade of the year 30.

In his analysis, Vidal García limits the participation of Saulo Pablo in the martyrdom of Esteban by pointing out that the news about the presence of Pablo in that stoning would not belong to the original tradition used by Acts. Bornkamm argues about the difficulty of assume that Paul was even present at Stephen's stoning.

However, other authors (for example, Brown, Fitzmyer, Penna, Murphy O'Connor, etc.) do not find sufficient reasons to doubt the presence of Paul at Stephen's martyrdom. Always according to the Acts, the witnesses of the execution of Stephen put their clothes at the feet of "young Saul" (Acts 7, 58). Martin Hengel considers that Paul could have been about 25 years old at that time.

Chapter 8 of the Acts of the Apostles shows in the first verses a panoramic picture of the first Christian persecution in Jerusalem, in which Saul Paul is presented as the soul of that persecution. Without even respecting women, he took Christians to jail.

Saul approved his death. On that day a great persecution was unleashed against the Church of Jerusalem. All, except the apostles, dispersed through the regions of Judea and Samaria. Some pious men buried Stephen and made great mourning for him. Meanwhile Saul wrought havoc in the Church; he went into the houses, and men and women were forcibly taken, and put them in prison.Acts of the Apostles 8, 1-3

There is no talk of massacres but, in a later speech in the temple (Acts 22, 19-21), Paul pointed out that he had previously gone around the synagogues imprisoning and flogging those who believed in Jesus of Nazareth. In Acts 9,1 it is indicated that Saul's intentions and purposes were to intimidate the faithful to death. And in Acts 22:4 the persecution of him "unto death" is placed in Paul's mouth, chaining and imprisoning men and women.

Vidal García and Bornkamm express their distrust regarding the real scope of this persecution, both from the point of view of its geographical extension and its degree of violence. Barbaglio points out that the Acts make Paul appear, "not as the persecutor but as persecution personified", so they cannot be considered a neutral chronicle. Sanders argues that this persecution was due to the zeal of Saul Paul, and not because of his status as a Pharisee. Beyond the scope Precisely from its persecutory character, it could be summed up —in the words of Gerd Theissen— that the life of the pre-Christian Paul was characterized by "pride and ostentatious zeal for the Law".

The Conversion

By Caravaggio, in the Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, in Rome. In the works of art and popular belief is the image that Paul fell from his horse, when neither in the Pauline Epistles nor in the Acts of the Apostles mentions the fall of a horse. It could therefore be an anachronism.

According to the book of the Acts of the Apostles, after the martyrdom of Stephen, Saul Paul went to Damascus, a fact that biblical scholars tend to place in the year following Stephen's stoning, as discussed in the section above (see also the analysis by V. M. Fernández and the bibliography cited there).

Meanwhile Saul, still breathing threats and deaths against the disciples of the Lord, came to the High Priest, and asked him for letters to the synagogues in Damascus, so that if he found some followers of the Way, men or women, he could take them to Jerusalem. It happened that, on his way, when he was near Damascus, he suddenly surrounded a light coming from heaven, he fell on the ground and heard a voice saying to him, "Saul, Saul, why persecute me?" He said, "Who are you, Lord?" And he: "I am Jesus, whom you persecute. But get up, get in the city and you'll be told what you should do." The men who went with him had stopped mutes of terror; they heard the voice, but they saw no one. Saul arose from the ground, and though he had his eyes open, he saw nothing. They took him by the hand and brought him into Damascus. He spent three days without seeing, without eating and without drinking.Acts of the Apostles 9, 1-9

Paul himself presented this experience as a "vision" (1 Corinthians 9, 1), as an "appearance" of the risen Jesus Christ (1 Corinthians 15, 8) or as a "revelation" of Jesus Christ and his Gospel (Galatians 1, 12-16; 1Corinthians 2, 10). But he never presented this experience as a "conversion," because for the Jews to "convert" meant giving up idols to believe in the true God, and Paul had never worshiped pagan idols or led a dissolute life. Biblical scholars tend to limit the meaning of the term "conversion" as applied to Paul to a very precise framework. In fact, it is possible that Paul interpreted such an experience as not making him less Jewish, but allowing him to reach the deepest essence of the Jewish faith. At that time, Christianity did not yet exist as an independent religion.

There are several unresolved points regarding this story. For example, in 1 Corinthians 9:1 Paul pointed out that he "saw" Jesus, but nowhere in Acts (Acts 9:3-7; 22:6-9; 26:13-18) does this occur. Furthermore, the three passages in Acts do not agree on the details: if the companions were left standing unable to speak or if they fell to the ground; whether or not they heard the voice; likewise, the fact that Jesus spoke to Paul “in the Hebrew language”, but quoting a Greek proverb (Acts 26:14). However, the central core of the story always coincides:

- Saul, Saul, why are you after me?- Who are you, sir?- I am Jesus (of Nazareth), whom you persecute.

The Pauline epistles are silent on the details of this episode, although Paul's behavior before and after is pointed out by himself in one of them.

[...]for I received him not, nor learned of any man, but by the revelation of Jesus Christ. For you are already aware of my previous conduct in Judaism, how incarnately I persecuted the Church of God and devastated it, and how I surpassed in Judaism many of my contemporary compatriots, surpassing them in zeal for the traditions of my parents. But when the One who separated me from my mother's bosom and me Call. by his grace, it was well to reveal in me his Son, that he might proclaim him among the Gentiles, to the point, without asking for advice or flesh or blood, without going up to Jerusalem where the apostles before me, I went to Arabia, from which I returned to Damascus.Epistle to Galatians 1, 12-17

In another of his epistles he stated:

And ultimately [the Risen Christ] appeared also to me, as to an abortion.First Epistle to Corinthians 15, 8-9

As a result of that "experience" lived on the road to Damascus, Saul of Tarsus, until then dedicated to "fiercely persecuting" and "zealously ravaging" the "Church of God" according to his own words, It transformed his thinking and his behavior. Paul always spoke of his Jewish condition in the present tense, noting that he himself had to abide by the rules set by the Jewish authorities. He probably never abandoned his Jewish roots, but he remained faithful to that experience, considered one of the main events in the history of the Church.

After the event experienced by Paul on the road to Damascus, Ananias cured him of his blindness by laying his hands on him. Paul was baptized and remained in Damascus "for some days".

Scientific papers from the 1950s onwards suggested Pablo de Tarso's presumed epilepsy, and it was postulated that his vision and ecstatic experiences could be manifestations of temporal lobe epilepsy. A central scotoma was also proposed as a Paul's ailment, and that this pathology could have been caused by solar retinitis on the road from Jerusalem to Damascus. Bullock suggested as many as six possible causes of Paul's blindness on the road to Damascus: occlusion of the vertebrobasilar artery, occipital contusion, secondary vitreous hemorrhage/retinal tear, injury caused by lightning, Digitalis poisoning, or ulcerations (burns) of the cornea. However, the state of physical health of Pablo de Tarso remains unknown.

His Early Ministry

Paul of Tarsus began his ministry in Damascus and Arabia, a name by which reference was made to the Nabataean kingdom. He was persecuted by the ethnarch Aretas IV, a fact that is usually dated from the years 38-39, or possibly before the year 36.

Paul fled to Jerusalem where, according to the Epistle to the Galatians (1, 18-19), he visited and conversed with Peter and James. According to the Acts (9, 26-28), it was Barnabas who took him before the apostles. It could be interpreted that it was then that they transmitted to Paul what he later mentioned in his letters having received by tradition about Jesus. His stay in Jerusalem was brief: he would have been forced to flee Jerusalem to escape from the Greek-speaking Jews. He was taken to Caesarea Maritima and sent to take refuge in Tarsus in Cilicia.

Barnabas went to Tarsus and went with Paul to Antioch, where the name “Christians” first arose for the disciples of Jesus. Paul would have spent a year evangelizing there, before being sent to Jerusalem to help those suffering from famine. Antioch would become the center of Christian converts from paganism.

Mission Trips

From the year 46 the three great missionary journeys of Paul began, which modern revisionism interprets began earlier, after the year 37. The three journeys are actually a classification for didactic purposes.

Extent of trips

Paul generally made his trips on foot (2 Corinthians 11, 26). The effort made by Paul of Tarsus on his travels is noteworthy. If only the number of kilometers of the three trips through Asia Minor is counted, the following result can be given, according to Josef Holzner:

- First trip: from Atalia, the port to which it arrived from Cyprus, to Derbe, back and forth, 1 000 km.

- Second trip: from Tarso to Tróade, 1 400 km. If you take into account the displacement by Galacia to your capital, Ancira, you have to add 526 km more. Thus, only within Asia Minor traveled at least 1 926 km. This calculation of minimums is because the narrative of the Acts of the Apostles is very general and is limited to saying that it crossed the region of Galatia and Misia.

- Third trip: from Tarsus to Ephesus, 1 150 km. To this we must add the route through the region of Galacia. On this journey, only in Asia Minor traveled minimum 1 700 km.

To the above we should add the trips by land in Europe and by sea, the difficult roads, the differences in altitude, etc. In a very vivid way, Paul himself described in the following passage what these journeys entailed:

I've been in danger of death many times. Five times I received from the Jews forty strokes but one. Three times I was beaten with rods; once I was stoned; three times I suffered a shipwreck; one day and one night I spent in the abyss. Frequent travels; dangers of rivers; dangers of sprinklers; dangers of my race; dangers of the Gentiles; dangers in the city; dangers in depopulation; dangers in the sea; dangers between false brothers; jobs and fatigues; nights without sleep, many times; hunger and thirst; many days without eating; cold and nakedness. And besides other things, my daily responsibility: the concern for all the Churches. Who fails without me failing? Who suffers scandal without me opening?2 Corinthians 11, 23c-29

In effect, as a traveler unprotected from any escort, you would be an easy victim of bandits, particularly in rural areas little frequented. Sea voyages were no safer: the winds could help heading east, but heading west was dangerous, and shipwrecks were common either way. Even in the great Greco-Roman cities like Ephesus, Paul was still a Jew, possibly with a bag on his shoulder, wanting to question the entire culture in the name of someone who had been considered a crucified criminal. Not even "his own" (those of his "class", "race" or "lineage", that is, the Jews) stopped sanctioning him. Finally, his work did not even end after preaching the gospel of Jesus Christ or forming a community.

The German Protestant theologian Gustav Adolf Deissmann emphasized the point when he commented in 1912 that he felt "unspeakable admiration" at the purely physical exertion of Paul, who could rightly say of himself that he "whipped his body and tamed it like a slave" (1 Corinthians 9:27).

First trip

Sent by the Church of Antioquia, Barnabas and Paul set out on their first missionary journey (Acts 13-14), accompanied by Juan Marcos, Barnabas's cousin who served as assistant. From the story it emerges that Barnabas would have directed the mission at the beginning. They set sail from Seleucia, a port of Antioch located 25 km from the city, towards the island of Cyprus, Barnabas's homeland. They traversed the island from Salamis on the eastern coast of Cyprus to Paphos on the western coast.

In Paphos, Paul achieved an illustrious convert in the person of the Roman proconsul Sergio Paulo. In his retinue was the magician Elymas, who tried to separate the proconsul from the faith. Paul called him "full of all deceit and wickedness, the son of the Devil and the enemy of all righteousness," and he blinded Elymas. Seeing what happened, the proconsul believed. From Paphos the missionaries sailed to Perge, in the Pamphylia region on the southern coast of central Asia Minor. It is here where the account of the Acts of the Apostles begins to call Saul with his Roman name Paul, who henceforth heads the mission. At this stage John Mark left them to return to Jerusalem, much to Paul's displeasure as noted below.

Paul and Barnabas continued their journey inland towards south-central Anatolia, touching the cities of southern Galatia: Pisidian Antioch, Iconium, Lystra and Derbe. The constant norm in Paul, as presented in the Acts, was to preach first to the Jews whom he supposed to be the most prepared to receive the message. The account of the Acts also shows the active opposition made by "those of his race" to the evangelical announcement. Faced with their open resistance, he declared his intention to address the Gentiles from now on. The pagans began to welcome him joyfully. Paul and Barnabas retraced the path from Derbe, through Lystra, Iconium, and Antioch of Pisidia, to Perge; They embarked from Athaliah for Antioch in Syria, where Paul spent some time with the Christians.

While the authentic epistles of Paul do not provide any information about this first journey, they mention instead that he preached to the Gentiles in advance of the Council of Jerusalem and that he suffered a stoning, which would have correspondence with that suffered in Lystra, according to the Acts.

Council of Jerusalem

After the first Pauline mission and during the brief stay of the Apostle in Antioch, some Judaizers arrived, whose preaching indicated the need for circumcision to be saved, for which they unleashed a no lesser conflict with Paul and Barnabas. The Church of Antioch sent Paul, Barnabas, and a few others (among them Titus, according to Galatians 2:1) to Jerusalem to consult the apostles and elders. In Paul's own words, this would be his second visit to Jerusalem after his conversion ("once more in fourteen years"). This event is traditionally dated from the year 49, while revisionist positions vary in the dating, between the years 47 and 51. According to Thiessen, this conflict triggered his own conversion in Paul, leading it to public debate as an argument to instruct about the risk involved in admitting circumcision.

Although with some nuances, this fact appears both in the Epistle to the Galatians and in the book of Acts, and gave rise to a cabal known as the Jerusalem Council, in which Paul's position on not to impose the Jewish ritual of circumcision on Gentile converts.

The decision adopted at the council implied an advance in the liberation of primitive Christianity from its Jewish roots to open itself to the universal apostolate. The issue resolved there seems to have been specific, although with doctrinal implications that would exceed the problem posed. Indeed, Paul would later denounce the uselessness of the cultic practices typical of Judaism, which included not only circumcision (Galatians 6, 12) but also observances (Galatians 4, 10), to finally lead to the conception that it is not man who achieves his own justification as a result of the observance of divine Law, but it is the sacrifice of Christ that justifies him freely, that is, that salvation is a free gift of God (Romans 3, 21-30).

Controversy in Antioch

After the Council of Jerusalem, Paul and Barnabas returned to Antioch where a major dispute would take place. According to Galatians 2, 12-14, having eaten with the Gentiles, Simon Peter abandoned this practice before the arrival of men from Santiago who objected to this practice.

Paul recognized the position of Peter, whom he considered one of the pillars of the Church in Jerusalem, but felt compelled to protest and "resisted him to his face". He warned Peter that he was violating his own principles and that he did not walk uprightly according to the truth of the gospel. It was not, therefore, a mere difference of opinion. According to Bornkamm, Paul saw in Peter's attitude a relapse into legalism, which turned its back on the gospel and what was previously agreed in Jerusalem, minimizing the importance of faith in Christ as superior to the law.

The end result of this incident is doubtful as to whether one opinion or the other prevailed. In either case, the conflict had consequences. According to the Epistle to the Galatians, Barnabas also took a position in favor of the men of Santiago, and this could be an additional reason for the separation of Paul and Barnabas, and for Paul's departure from Antioch in the company of Silas.

Second trip

On the second missionary journey Paul was accompanied by Silas. They set out from Antioch and, crossing the lands of Syria and Cilicia, reached Derbe and Lystra, cities in southern Galatia. At Lystra they were joined by Timothy (Acts 16:1-3), then through Phrygia he made his way to northern Galatia, where he founded new communities. From the Epistle to the Galatians it is known that Paul fell ill while crossing Galatia and that, during that unplanned stay, thanks to his preaching, the Galatian communities arose there. Not being able to continue towards Bithynia, he left Galatia for Mysia and Troad, where he stayed. presumes he was joined by Lucas.

He decided to go to Europe, and in Macedonia he founded the first European Christian Church: the community of Philippi. After suffering lashes with rods and imprisonment at the hands of Roman praetors in Philippi, Paul went to Thessalonica, where he had a short stay dedicated to evangelization, nuanced by his controversies with the Jews.

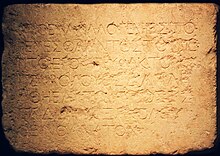

The hostility of Thessalonica seems to have distorted Paul's initial idea, which, according to the authors, would be to go to Rome, the capital of the Empire. This would be indicated by the fact that Paul traveled the renowned Via Egnatia until, after Thessalonica, he changed course to go deeper into Greece. Indeed, his stay in Thessalonica ended with the flight of Paul to Berea, and his subsequent trip to Athens, where he tried unsuccessfully to catch the attention of the Athenians, famous for their eagerness for news, with a speech on the Areopagus on the gospel of the risen Jesus. From there he proceeded to Corinth, where he stayed for a year and a half, welcomed by Aquila and Priscilla, a Judeo-Christian couple who had been expelled from Rome due to the edict of Emperor Claudius, and who would become close friends of Paul. During his stay in Ephesus, Paul was brought before the court of Gallio, proconsul of Achaia. This is Lucius Junius Anneo Gallio, older brother of the philosopher Seneca, whose mandate is mentioned in the so-called Delphi inscription, epigraphic evidence that was originally found in in the temple of Apollo, discovered in Delphi (Greece) in 1905. From a historical point of view, this evidence is considered key and secure, and allows Paul's presence to be dated from the years 50 to 51. Corinth. In the year 51, Paul wrote the First Epistle to the Thessalonians, the oldest document in the New Testament. The following year he returned to Antioch.

Third trip

The third trip of Pablo de Tarso was undoubtedly complex, and framed his most suffered mission, for various reasons. This stage included the experience of very strong opposition (in his own words, "wild beasts" and "many adversaries") and tribulations (with probable imprisonment) that came to "overwhelm" the Apostle, in addition to being marked by the crises that shook the communities of Galacia and Corinto and that motivated the intervention of Pablo and his team, through his own letters and personal visits. However, in the end it was one of the most fruitful missions. Traditionally this stage is dated from the years 54 to 57, while the revisionist positions tend to place it between the years 51 and 54. At that stage of his life, Pablo wrote a good part of his epistolary work.

From Antioch, Paul passed through northern Galatia and Phrygia "to confirm all the disciples" who were there, and continued to Ephesus, the capital of Asia Minor, where he established his new mission headquarters, and from where he evangelized the entire area of influence accompanied by the team he led.

First he addressed the Jews in the synagogue but, after three months they continued to express their disbelief, he began to teach at the "school of Tirano". No further information is available about this "school". However, this brief notice is considered true, even by those who distrust the Acts of the Apostles (for example, Helmut Köester, a disciple of Bultmann, Bornkamm and Käsemann). Some conjecture that it would be of a rhetoric school that rented the premises to Paul during his free hours. The Western text (Beza's codex) indicates that Paul taught there from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. tenth"). If this news is true, it could be an early form of catechism, carried out on a regular basis. But according to Vidal, it is possible that Paul's daily teaching at "the school of Tirano" pointed to a kind of Pauline theological school in that city, a place of study of issues related to the interpretation of Scripture.

Shortly after arriving in Ephesus, Paul would have written his letter to the churches of Galatia, motivated by the claims of some Judaizing missionaries opposed to the Apostle, who demanded circumcision of Galatian Christians of Gentile origin. Both the letter, a manifesto of Christian freedom to oppose the attempted Judaization of those Churches, like its bearer Titus, succeeded in achieving the preservation of the Pauline identity of the communities of Galatia.

Also at this stage, news reached Paul's ears about serious problems that had arisen in the Church of Corinth: formation of factions within the community, animosity against Paul himself, scandals, and various doctrinal problems, all of which are known. news only because of their letters. Pablo wrote at least four epistles to them (according to Vidal García, op.cit., up to six). Of them, the two known ones have been preserved until today, probably resulting from a merger by a compiler, perhaps at the end of the century I, from the fragmented originals of four. The first two letters, today probably merged into what we know as the First Epistle to the Corinthians, constituted serious warnings to that community against the dramatic divisions within it, as well as against some cases scandalous, such as the incestuous conjugal union, and the practice of prostitution. The problems with this community continued, fomented by some missionaries clashing with the Pauline team. This gave rise to the third letter, represented today by the fragment of 2 Corinthians 2, 14 - 7, 4. Between the third and fourth letters, Paul went to Corinth in what constituted a painful visit: he met with a Church raised against him, which even publicly offended him. On his return to Ephesus, Paul wrote the fourth letter to the Corinthian community (2 Corinthians 10, 1-13, 13), known as the Letter of tears. It was not just an apologetic defense message against his adversaries, but it was loaded with emotion.

Paul's stay in Ephesus for 2 or 3 years is considered safe. Among the events narrated in Acts are Paul's confrontation with the seven exorcist sons of a Jewish priest and the so-called "revolt of the silversmiths", a hostile uprising provoked by a certain Demetrius and seconded by other goldsmiths dedicated to the goddess Artemis. Paul's preaching would have irritated Demetrius, who made small shrines of silver copying that of Artemis of Ephesus, with not a little profit for him.

"Compañeros, you know that we owe well-being to this industry; but you are seeing and hearing that not only in Ephesus, but in almost all Asia, that Paul persuades and separates many people, saying that it is not gods that are made with hands. And this not only brings the danger that our profession will fall into disrepute, but also that the temple of the great Artemis goddess will be held in nothing and will come to be stripped of its greatness that worships all Asia and all the earth."Words of Demetrius, according to the Acts of the Apostles 19, 25-27

The tone of the account of the Acts and the picture it describes is different from that of the Pauline epistles, for which some scholars are not sure of its historicity. On the other hand, others, even pointing out the absence of these news in the writings of Paul, they find in his letters possible allusions to the tumultuous stay of the Apostle in Ephesus. The difficulties that Paul would have suffered in Ephesus suggest that the Apostle could have suffered imprisonment there. This possibility is important not only as a biographical fact, but also when it comes to dating the time and place in which Paul wrote his Epistle to the Philippians and the Epistle to Philemon, whose redactions, according to the Apostle himself, took place while he was a prisoner (Philippians 1, 12-14; Philemon 1, 8-13).

It cannot be ascertained whether, after his stay in Ephesus, Paul immediately marched to Corinth or crossed from Macedonia to Illyricum, for the first time, for a brief evangelistic visit. In any case, Paul arrived in Corinth, in what would probably be his third visit to that city. He stayed three months in Achaia.

At that time Paul wrote what, according to most specialists, was the last surviving letter of his authorship: the Epistle to the Romans, dated from the years 55 to 58. This letter is the oldest testimony of the existence of the Christian community in Rome, and its level of importance is such that Bornkamm comes to refer to it as "Paul's testament". Paul then points out his plan to visit Rome, and from there go to Hispania and the West.

Meanwhile, Paul had been thinking about returning to Jerusalem. At that time he tried to get his Gentile churches to collect a collection for the poor in Jerusalem. When he had already decided to embark in Corinth for Syria, some Jews plotted a conspiracy against him and Paul decided to return by land, through Macedonia. Accompanied by some disciples from Berea, Thessalonica, Derbe, and Ephesus, Paul sailed from Philippi to Troas, then passing through Aso and Mytilene. Skirting the coast of Asia Minor, he sailed from the island of Chios to the island of Samos and then to Miletus, where he delivered an important speech to the elders of the Church of Ephesus summoned there. He then sailed to the island of Cos, Rhodes, Patara in Lycia and Tire in Phoenicia, Ptolemais and Caesarea Maritima. By land he reached Jerusalem, where he would have managed to deliver the collection that he had collected so hard.

It is known from the Epistle to the Romans 15 that Paul viewed his return to Jerusalem with some concern, both because of the possibility of being persecuted by the Jews and because of the reaction that the Jerusalem community might have towards him and towards the collection made by the communities he had founded. Surprisingly, the Acts of the Apostles does not comment on the delivery of the collection, which could be an indication of a conflictive ending in which Paul was unable to dissolve the misgivings that still persisted in the Jerusalem community regarding his preaching.

Paul's arrest and death

The last stage of Paul's life, which spans from his arrest in Jerusalem to his presence in Rome, has as its fundamental source the account of Acts of the Apostles 21, 27 - 28, 31, although the author of Acts does not deals with the death of the Apostle. Although qualified authors of various extractions recognize that the story does not meet strict criteria of historicity in detail, however, it is also considered that the story treasures various undoubtedly reliable historical news.

James advised Paul that his behavior during his stay in Jerusalem be that of a pious and observant Jew, and Paul agreed, all of which is considered credible. As the ritual period of seventy days was about to expire, Some Jews from the province of Asia saw Paul in the Temple precincts and accused him of sponsoring a violation of the Law and of having desecrated the sanctity of the Temple by introducing some Greeks into it. They tried to kill him in a riot, from which he was extricated by the arrest by the tribune of the Roman cohort based in the Antonia Fortress. Taken before the Sanhedrin, Paul defended himself and ended up stirring up a dispute between the Pharisees and the Sadducees., since the latter did not believe in the resurrection while the Pharisees did. Subsequently, the Jews would have conspired to kill Paul but the tribune sent him to the attorney for the province of Judea, Marco Antonio Félix, who resided in Caesarea Maritima, before whom he defended himself again. The procurator postponed the trial and left Pablo in prison for two years. Bornkamm considers that both Pablo's transfer to Caesarea Maritima and the postponement of his trial are reliable data from historical criticism. The case was reviewed only after the arrival of the next procurator, Porcius Festus. Because of his appeal to Caesar, Paul was sent to Rome. The more traditional chronology of Paul's life placed the writing of the Epistle to the Philippians and the Epistle to Philemon in this period of Paul's captivity at Caesarea Maritima, or later. in his prison in Rome.

From Paul's risky journey to Rome as a prisoner, some reliable information can be obtained, including the long duration of the journey, the escort he was subjected to, and a forced detention on the island of Malta, which could have been be extended for three months.

The book of the Acts of the Apostles gave the arrival of Paul to Rome an additional importance to the mere historical character: for him it meant the fulfillment of what he considered already foreseen by Jesus at the beginning of the same book regarding that the The Gospel would be taken to all nations. Some scholars also point to a certain apologetic irony in the way the Acts of the Apostles describes Paul's arrival in Rome: not by free will, as he had proposed a decade earlier. without achieving it, but as a prisoner subject to Caesar, with which the Romans became indirect agents of the consolidation of the gospel in the very center of their Empire.

Paul's captivity in Rome, considered a reliable fact, would have lasted two years, a time during which the Apostle did not live in prison but in custody, which, however, limited his freedoms.

One of the issues for which there is no clear definition is whether, after Paul's home custody in Rome, he was released followed by some other trip (for example, if he carried out his plan to travel to Hispania), before dying in Rome itself. This hypothesis is favored by the First Epistle of Clement and the Muratorian Fragment. At present, these news tend to be disregarded as lacking sufficient support. It is reasonable to think that the author who finished writing the Acts of the Apostles around the year 80 knew the end of Pablo. If Pablo had been released earlier from his prison, this would have been indicated in the book, which is not the case. Both those who think that Pablo arrived in Tarraco, and those who think that he never arrived, admit that at the moment it is not possible to a clear and definitive conclusion on the subject, although —according to the professor of New Testament and dean of the Faculty of Theology of Catalonia Armand Puig i Tàrrech— there are reasons to affirm as "plausible and highly probable" that Paul carried out a mission in Tarragona in painful conditions due to his status as an exile.

On the other hand, both the ecclesiastical tradition and the historiographical and exegetical analyzes agree that Paul's death occurred in Rome under the government of Nero, and that it had a violent nature.

Ignatius of Antioch already pointed to Paul's martyrdom in his Letter to the Ephesians XII, probably written in the first decade of the century II. Regarding the date, there is a tradition of his death at the same time as Peter (year 64) or a little later (year 67). It lasted between the years 54 and 68, and most modern authors tend to point out that the Apostle's death occurred earlier than Eusebius of Caesarea pointed out, more precisely in the year 58, or at most at the beginning of the year. of the decade of the year 60.

Eusebius of Caesarea describes that "it is recorded that Paul was beheaded in Rome itself, and that Peter was also crucified under Nero."

Tertullian describes Paul suffering a death similar to that of John the Baptist, who was beheaded:

How happy is your church, in which the apostles poured out all their doctrine along with their blood! Where Peter endured a passion like that of his Lord! Where Paul won his crown in a death like that of John (the Baptist).

Dionysius of Corinth, in a letter to the church in Rome (AD 166-174), stated that Paul and Peter were martyred in Italy. Eusebius also quotes the passage from Dionysius.

Lactantius tells us in his work On the death of the persecutors (318 AD) the following:

He was the first to pursue the servants of God. He crucified Peter and he killed Paul.

Saint Jerome, in his work De Viris Illustrubs (392 AD), mentions that "Paul was beheaded in the fourteenth year of Nero and that he was buried on the Via Ostia in Rome".

The apocryphal text written in the year 160 known under the title Acts of Paul indicated that Paul's martyrdom would have been by beheading.

Burial and worship

It is documented how the cult of Paul quickly developed in Rome and how it later spread to different European and North African locations.

Among the oldest sources linking Paul's death to Rome are the testimony of his burial on the via Ostiensis by the presbyter Caius at the end of the century II or early III century, and a IV century liturgical calendar on the burial of martyrs.

I can show you the trophies of the Apostles; if you want to go to the Vatican or Ostiense, you will find the trophies of the founders of this Church.Caius, collected by Eusebius of Caesarea, Ecclesiastical History II, 25:7

Similarly, the Paul's Passion of Pseudo Obadiah (VI century) marked the burial del Apóstol "outside the city [...], in the second mile of Via Ostiense", more precisely "in Lucina's farm", a Christian matron, where the Basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls would later be built.

Around the V century, the apocryphal text of Pseudo Marcellus, known under the title Acts of Peter and Paul 80, pointed out that Paul's martyrdom would have been by beheading at the Acque Salvie, on Via Laurentina, today Tre Fontane Abbey, with a triple rebound from his head that ensured have caused the generation of three waterways. This news is independent of all the previous and late, which suggests its legendary character.

Following a series of excavations carried out in the Roman basilica of Saint Paul Outside the Walls since 2002, in 2006 a group of Vatican archaeologists discovered skeletal human remains in a marble sarcophagus located under the main altar of the temple. The tomb dates from around the year 390. Using the carbon-14 measurement dating technique, it was possible to determine that the skeletal remains date from the 1st century. or II. In June 2009, Pope Benedict XVI announced the results of the investigations carried out up to that time and expressed his conviction that, based on the background, location and dating, it could be the remains of the Apostle.

Evaluations of Pablo de Tarso

Both during his lifetime and in subsequent generations, the figure and message of Paul of Tarsus were the subject of debate, generated sharply contrasting value judgments, and even provoked extreme reactions. In fact, Clement of Rome himself suggested that Paul was put to death "out of jealousy and envy".

On the one hand, three of the apostolic fathers of the first and second centuries, Clement of Rome, Ignatius of Antioch (particularly in his Letter to the Romans) and Polycarp of Smyrna (in his Epistle to the Philippians), referred to Paul and expressed their admiration for him. Polycarp went so far as to express that he would not be able to approach "the wisdom of the blessed and glorious Paul":

"For neither I nor any other like me can compete with the wisdom of the blessed and glorious Paul, who, dwelling among you, in the presence of the men of that time, taught punctually and firmly the word of the truth; and then absent, wrote unto you letters, with whose reading, if ye know how to delve into them, ye may build up in order the faith that was given unto you [...]."Smirna's cop, Epistle to the Philippians III

On the other hand, the Judeo-Christian current of the primitive Church tended to be refractory to Paul, whom it could consider a rival of Santiago and Pedro, the leaders of the Church of Jerusalem. Hence, specialists such as Bornkamm interpret that the Second Epistle of Peter, a late canonical writing dating from the years 100-150, expresses a certain "caution" regarding the Pauline epistles. Although this letter mentions Paul as "dear brother", it seems to treat his writings with some reserve because of the difficulties that could arise in his understanding, with which "the weak or unformed could twist his doctrine, to their own destruction" (2 Peter 3, 15-16).

Subsequent Church fathers endorsed and used Paul's letters on a sustained basis. Irenaeus of Lyon, at the end of the II century and with regard to the apostolic succession in the different churches, pointed out Paul next to Peter as the basis of the Church of Rome. Against the extremisms, both of the anti-Pauline Judeo-Christians and of Marcion and of the Gnostics, Irenaeus himself presented his position according to which there was consonance between the gospels, the Acts of the Apostles, the Pauline letters and the Hebrew Scriptures:

We are yet to add to the words of the Lord Paul, to examine his thought, to expose the apostle, to clarify all that he has received from other interpretations by the heretics, who do not understand the least of what Paul said, to show the stupidity of his madness and to demonstrate, precisely from Paul — from whom they draw their objections against us — that they are liars, while the apostle, herald of the truth, taught the whole [...]Ireneo de Lyon, Adversus haeres IV, 41, 4.

Perhaps the culmination of the influence of Paul of Tarsus among the fathers of the Church took place in the theology of Augustine of Hippo, particularly against Pelagianism. The notable diversity of assessments of the figure and work of Paul continued through time, and can be summed up in the words of Romano Penna:

Saint John Chrysostom exalted him as superior to many angels and archangels (cf. Paneg7.3); Martin Luther argued that there was nothing in the world as bold as his preaching (cf. Tischr2.277); an Iberian heretic of the s. VIII, Mygetius, even proclaimed that in him the Holy Spirit had been incarnated; and a scholar from the beginning of the s. XX considered him the second founder of Christianity (W. Wrede). Other definitions are more common, such as "the greatest missionary", "the thirteenth apostle", "the first after the One" or, more simply, the "fall of choice" (which Dante, Inf. 2,28, takes Acts 9, 15).R. Penna

The interpretations of the writings of Paul of Tarsus made by Martin Luther and John Calvin had an important influence on the Protestant Reformation of the XVI century. In the 18th century, the Pauline epistolary was a source of inspiration for the movement of John Wesley in England. In the 19th century, open hostility against Paul resurfaced. Perhaps the most extreme detractor of his ferocity has been Friedrich Nietzsche in his work The Antichrist , where he accuses Paul and the first Christian communities of totally distorting the message of Jesus:

The “good news” immediately happened to the worst of all: that of Paul [...] Life, the example, doctrine, death, sense, and the right of the whole gospel, all ceased to exist when this falsehood of hatred understood that it was the only thing I could use. Not reality, not historical truth! [...] It simply erased yesterday, the night before Christianity, invented a story of "primitive Christianity" [...] Later the Church even falseed the history of humanity, making it prehistory of Christianity...Friedrich Nietzsche, The Antichrist42.

Paul de Lagarde, who preached a "German religion" and a "national church", attributed what he considered the "disastrous evolution of Christianity" to the fact that "an absolutely incompetent person (Paul) managed to influence the church" At the antipodes, the dialectical theology of Karl Barth, a relevant intellectual precedent in the fight against National Socialism, was born with the 1919 commentary of this Swiss theologian on the Letter to the Romans.

However, Raymond E. Brown warned about two tendencies: (1) the one that tends to maximize certain anachronistic perspectives referred to Paul, and (2) the one that extremes the different positions that could have existed in the first Christian communities Beyond the differences between Pauline Christianity on the one hand and the Judeo-Christianity of James and Peter on the other, they maintained a common faith. And the late date of the writing of the Second Epistle of Peter allows us to suppose that the differences The differences of opinion existing between the different basic currents of primitive Christianity did not stifle its internal plurality, as it crystallized in the biblical canon.

Pauline Themes

Redemption

The theology of redemption was one of the major issues addressed by Paul. Paul taught that Christians were redeemed from the Law and from sin by Jesus' death and resurrection. His death was an atonement and therefore With the blood of Christ, peace was established between God and man. By baptism, a Christian takes his part in the death of Jesus and in his victory over death, freely receiving a renewed status as a child of God.

Relation to Judaism

Paul was a Jew, of the school of Gamaliel, of the Pharisee denomination, mentioning the latter as something he was proud of (Phil 3:5). The main point of his message was that the Gentiles do not need to be circumcised like the Jews (1Cor 3:2), in fact a good part of his teachings is an emphasis on the Gentiles so that they understand that their salvation does not depend on copy Jewish rituals; but both Jews and Gentiles, ultimately, are saved by Divine grace [of course, Divine grace is applied through Faith (fidelity)]. Contemporary scholars, however, debate whether when Paul speaks of "faith/faithfulness in/of Christ" (the Greek genitive is susceptible to both interpretations, objective and subjective) refers in all cases to faith in Christ as something necessary to achieve salvation (not only on the part of the Gentiles, but also of the Jews) or if in certain cases it refers rather to the fidelity of Christ himself towards men (as an instrument of divine salvation directed to Jews and Gentiles alike)

He was the pioneer in understanding that the message of salvation of Jesus that began in Israel, expanded to all creatures regardless of their origin. For Saul (in Hebrew: Shaúl) the gentile followers of Jesus should not follow the commandments of the Torah (law) that are exclusive to the people of Israel. And so it is established in the Council of Jerusalem (Gal 2:7-9), that the Gentiles must only keep the precepts of the Gentiles (commonly known in Judaism as: Noahide precepts; Hch 21:25; Talmud, Sanhedrin 56a and b).

Many of his teachings, when addressed to a Gentile people, were misunderstood and misinterpreted (2P 3:15-16). Some Jews on the one hand interpreted that Paul taught to abandon the Torah of Moses (Acts 21:28; Acts 21:21), which was not true, and he himself had to deny it (Acts 25:8; Acts 21:24,26). On the other hand, there were Gentiles who interpreted that salvation by grace allowed them to sin, and they also had to deny it (Rom 6:15).

Recently, some researchers such as Krister Stendahl, Lloyd Gaston, John G. Gager, Neil Elliott, William S. Campbell, Stanley K. Stowers, Mark D. Nanos, Pamela Eisenbaum, Paula Fredriksen, Caroline Johnson Hodge, David J. Rudolph and, in Spain, Carlos A. Segovia, have argued that Paul did not seek to overcome or reform Judaism, but rather to incorporate Gentiles into Israel through Christ without forcing them to renounce their Gentile status. This interpretation receives the name "radical new approach to Paul" and contrasts both with his traditional Christian interpretation and with the so-called "new perspective on Paul" by James D. G. Dunn and Nicholas Thomas Wright, according to which Paul set out to reform Judaism.

Role of women

A verse in the First Epistle to Timothy, traditionally attributed to Paul, is often used as a major source of authority in the Bible for women being barred from the sacrament of Holy Orders, in addition to other positions of leadership and ministry in the Christianity. The Epistle to Timothy is also often used by many churches to deny them the vote in ecclesiastical matters and teaching positions for adult audiences and also permission for missionary work.

11 May the woman learn in silence and with all restraint;

12 I do not allow women to teach or exercise dominion over men, but to remain silent.13Because Adam was first formed, and then Eve.

14and the deceived was not Adam, but the woman, being deceived, committed transgression;1 Timothy 2, 11-14

This passage seems to be saying that women should not have any leadership role vis-à-vis men in the church. Whether she also forbids women from teaching other women or children is doubtful, as even the Catholic Church—which prohibits the ordination of women to the priesthood—allows abbesses to teach and assume leadership positions over other women. Any interpretation of this part of Scripture has to grapple with the theological, contextual, syntactical, and lexical difficulties of these few words.

Theologian JR Daniel Kirk found an important role for women in the early Church, such as Paul praising Phoebe for her work as a deaconess and also Junia, considered by some to be the only woman to be quoted in the New Testament among the apostles. Kirk points to recent studies that led some to conclude that the passage forcing women to "be quiet in churches" in 1 Corinthians 14:34 was a later addition, apparently by a different author, and was not part of Paul's original letter to the Corinthian church. Others, like Giancarlo Biguzzi, claim that Paul's restriction on women in Corinthians is genuine, but applies to the particular case of forbidding them from asking questions or from conversing, and not a general prohibition against women speaking, for in 1 Corinthians 11, 5 Paul affirms the right of women to prophesy.

Kirk's third example of a more inclusive vision is in Galatians 3:28 Announcing an end within the Church to the divisions that were so common around the world, he concludes by noting that "...there were New Testament women who taught and had authority in the early Church and that these teachings and this authority were sanctioned by Paul and that the apostle himself offers a theological paradigm within which overcoming the subjugation of women is a expected result".

Character and legacy of Paul

Paul's character and legacy were verified: (1) in the communities founded by him and in his collaborators; (2) in authentic letters from him; and (3) in the so-called Deutero-Pauline letters, perhaps arising from a school that was born and grew up around the Apostle.It is from this immediate legacy that all his subsequent influence arose.

Communities and partners

Paul used impassioned language towards his communities and collaborators. To the Thessalonians he wrote that they were his hope, his joy, his crown, his glory; to the Philippians he told them that God was witness to how much they loved with the endearing love of Jesus Christ, and that shone like torches in the world. He warned the members of the Corinthian community that he would not be lenient with them, but not before commenting that he had written them with many tears to that they knew how great was the love that he had for them.

It is speculated that Paul must have been a man capable of arousing deep feelings of friendship, since his letters show loyalty on the part of a wide range of personalities with their own names. Timothy, Titus, Silas, all were part of of the Pauline team, carrying his letters and messages, sometimes in difficult circumstances. The Christian spouses Priscilla –also called Prisca– and Aquila, whose friendship towards Paul of Tarsus was endearing, were able to pitch their tent and leave with him from Corinth to Ephesus and then go to Rome, from where they had previously been exiled, to prepare the arrival of the Apostle. Vidal suggests that in Ephesus it was they who, in a risky intervention, would have achieved the release of Paul, which justified the praise of the Apostle:

Greet Prisca (Priscila) and Aquila, my collaborators in Christ Jesus. They exposed their heads to save me. And I am not only grateful to you, but also to all the Churches of Gentileness.Paul, Epistle to the Romans 16, 3-4

To them is added Lucas, who by tradition is identified with the author of the homonymous gospel and the Acts of the Apostles. His name is mentioned among those of Paul's collaborators.According to the Second Epistle to Timothy, he would have accompanied Paul until the end of it (2 Timothy 4, 11).

The Authentic Pauline Epistles

The authentic letters of Paul are a set of New Testament writings made up of the following works:

- the First Epistle to the Thessalonians

- the Epistle to the Philippians

- the First Epistle to the Corinthians

- the Second Epistle to the Corinthians

- the Epistle to the Galatians

- the Epistle to Philemon

- the Epistle to the Romans.

This corpus of authentic epistles is unique in more ways than one:

- Because his author is known to be certain, and his authenticity is widely recognized from the current scientific-literary analysis.

- Because his writing date is the oldest of the New Testament books, just 20-25 years after the death of Jesus of Nazareth, and probably even before that of the Gospels in his definitive version known today, so they constitute documentation of a capital character in any analysis of the beginnings of Christianity.

- Because no other New Testament personality is known on a similar level through its writings.

Paul's knowledge of Hellenic culture—he was fluent in both Greek and Aramaic—enabled him to preach the Gospel using examples and comparisons common to Hellenic culture, so his message was quickly successful in Greek territory. But this characteristic also made it difficult at times to accurately understand his words, since Paul sometimes resorted to Hellenistic notions far removed from Judaism, while other times he spoke as a strict and law-abiding Jew. Hence, in Antiquity some of his statements were qualified as "τινα δυσνοητα" (transliterated, tina dysnoēta , which means "difficult to understand" points; and that until today there are polemics in the interpretation of certain passages and themes of the Pauline letters, such as, for example, the relationship between Jews and Gentiles, between grace and Law, etc. On the other hand, it is clear that his epistles were written on occasion, responses to specific situations. modern exegetical analysis, rather than expecting from each of them a systematic formulation of the Apostle's thought, examines the difficulties and particularities that he presents, analyzes his evolution and debates about his integrity.

Although the letters had the immediate function of addressing problems resulting from specific situations, it is very likely that the communities to which these letters were addressed treasured them, and that they soon shared them with other Pauline communities. Thus, it is highly probable that by the end of the century I these writings already existed as corpus, resulting from the work of a school Paulina who compiled his letters to form the written legacy of the Apostle.

The Pseudepigraphic Epistles

In addition to Paul's letters, there is a group of epistolary writings that are presented as his but that modern criticism, aware of the phenomenon of pseudepigraphy typical of ancient Eastern and Greek works, attributes to different authors associated with Paul. These are the following works:

- the Second Epistle to the Thessalonians

- the Epistle to the Colossians

- the Epistle to the Ephesians

- the First Epistle to Timothy

- the Second Epistle to Timothy

- Epistle to Titus.

The fact that these canonical writings are suggested to be pseudepigraphical or deuteropauline, far from diminishing the Apostle's notoriety, they increased it, because it means that a "school", perhaps already established around Paul himself and depositary of his legacy, resorted to the authority of the Apostle to validate his writings.

Pauline theology

Pauline theology is called the reasoned, systematic and comprehensive study of the thought of Paul of Tarsus, who underwent developments and adjustments in the successive interpretations that were made of his writings. The summary presentation of Saint Paul's theology is very arduous. The greatest difficulty in any attempt to systematize the Apostle's thought lies in the fact that Paul was not a systematic theologian, which is why any categorization and ordering seems to respond more to the exegete's questions than to Pauline schemes.

For a long time the debate was subject to a dilemma. According to the classical Lutheran thesis, the fundamental theme of Pauline theology would be that of the justification of the faith without the works of the Law. From this thesis it came to be considered that in the Pauline doctrine understood in this way was the central nucleus of the proclamation Christian. In the XX century, the position in favor of the sola fide principle was a constant in the background and orientation of Rudolf Karl Bultmann's thought and was also presented, with a variety of nuances, in followers of his such as Ernst Käsemann or G. Bornkamm.

From the point of view of Catholicism, although justification is part of the Pauline message, it does not constitute its unique core. The traditional Catholic argument held that God, rather than "declaring man just", makes man just by transforming him.

In recent years, different Protestant scholars, such as Krister Stendahl, Ed Parish Sanders, and James D. G. Dunn, have criticized the classical Lutheran position that pitted a Christian faith that bears grace and freedom against a presumed traditional Judaism fond of legalism and arrogant exaltation of the observance of Mosaic prescriptions. After presenting the difficulty of "writing a theology of Paul", James Dunn proposed in his book as an outline the following: God and humanity - humanity under interdiction - the Gospel of Jesus Christ - the beginning of salvation - the process of salvation – the Church – ethics.

Catholic authors (Lucien Cerfaux, Rudolf Schnackenburg, and particularly Joseph A. Fitzmyer) centered Paul's theology on his thinking about Christ, particularly his death and resurrection. J. Fitzmyer pointed to Christology as the center of Pauline theology. For him, Pauline theology would be a Christocentric theology, that is, a theology whose main axis is Christ dead and risen. Other authors such as Joachim Gnilka and Giuseppe Barbaglio speak of a Pauline theocentrism, which means that all of Paul's thinking starts from God and returns to Him.

On the other hand, a detailed observation of the authentic Pauline epistles allows us to notice that an evolution took place in the Apostle's thought and that, consequently, one could not speak of a single center of interest in his preaching. G. Barbaglio proposed that the Apostle writes a "theology in epistle." Hence, Barbaglio's scheme consisted of presenting the theology of each letter following chronologically each of the seven authentically Pauline epistles, to end with a chapter entitled: "Coherence of Paul's theology: hermeneutics of the Gospel".

According to R. Penna, there is a tendency to accept that the «Christ-event» is at the center of Paul's thought, a conclusive fact in «his theology». The discussion goes on about the consequences (anthropological, eschatological, ecclesiological) of this data. Brown suggested that all of the propositions contain some truth, but derive from post-Paul "analytic judgments".

Artistic representations

Paul, like other relevant apostles, had extensive treatment in art. In particular, his conversion episode was treated by Italian masters such as Parmigianino (Vienna Art History Museum), Michelangelo (mural in the Pauline Chapel of the Apostolic Palace in Vatican City) and Caravaggio (Basilica of Santa Maria del Popolo, Rome). Other frequently chosen moments were the preaching in the Areopagus (Raphael, Sistine Chapel -he also painted the rejection of the magician Elymas and the sacrifice of Lystra-), the descent in a basket from the walls of Damascus, the shipwreck, the episode of the serpents, ecstasy, prison stay and martyrdom.

He does not usually appear in the series referring to the twelve apostles who knew Christ while alive, but very often he is represented in a couple with Simon Peter. In this case they are usually distinguished by their attributes: in Saint Peter, the keys that symbolize his election as head of the Church, and in Saint Paul the sword that symbolizes his martyrdom -in addition to referring to a passage from his letter to the Ephesians: the sword of the Spirit, which is the word of God-). The presence of a book that represents his status as author of New Testament texts is also frequent (although this also identifies Peter and other apostles). Peter and Paul are sometimes depicted as debating theologians.

The origin of its iconography, which establishes characteristic and repeated features throughout the centuries, goes back to paleo-Christian art, which connects it with the Greco-Roman tradition of representation of philosophers such as Plotinus.

Biblical quotes

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 11, 23-29.

- ↑ Acts 7, 58; Acts 8, 1-3; Acts 9,1

- ↑ 1 Samuel 9, 2; 1 Samuel 10, 1.

- ↑ Acts 9, 4.17; Acts 22, 7.13; Acts 26, 14.

- ↑ Acts 13, 9

- ↑ Acts 16, 39. 22, 27-28. 25, 10.

- ↑ Acts 20, 24.

- ↑ Philemon 1, 9.

- ↑ Philemon 1, 1.

- ↑ Acts 9, 11; 21, 39; 22, 3.

- ↑ Acts 22, 22-29.

- ↑ Acts 16, 37-38; 22, 25-29; 23, 27.

- ↑ Romans 11, 1; Philippians 3, 5.

- ↑ Acts 22, 3.

- ↑ Acts 26, 5.

- ↑ Galatians 1, 13; Philippians 3, 6.

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 11, 22; Galatians 2, 15; Philippians 3, 3-6.

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 11, 24.

- ↑ Acts 9, 10-19.

- ↑ Galatians 1, 17.

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 11, 32.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 11, 23; 1 Corinthians 15, 3

- ↑ Acts 9, 29-30.

- ↑ Acts 11,25-30

- ↑ Acts 4, 36.

- ↑ Acts 13, 7-12.

- ↑ Acts 15, 38.

- ↑ Acts 14, 48-50.

- ↑ Acts 14, 28.

- ↑ Galatians 2, 9.

- ↑ Galatians 2, 11.

- ↑ Galatians 2, 14.

- ↑ Acts 15:36-40.

- ↑ Galatians 4, 13-20.

- ↑ Acts 16:16-40.

- ↑ Acts 17, 1.

- ↑ Acts 17, 10.

- ↑ Acts 17,

- ↑ Acts 17, 22-32.

- ↑ Acts 18, 11.

- ↑ Acts 18, 1-3.

- ↑ Acts 18, 12-17.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 15, 32.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 16, 8-9.

- ↑ 2 Corinthians 1, 8-9.

- ↑ Acts 18, 23.

- ↑ Acts 19, 8-10.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 1,10 - 4, 21.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 5, 1-13.

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 6, 12-20.

- ↑ Romans 15, 19.

- ↑ Acts 20, 2-3; 1 Corinthians 16, 5-6; 2 Corinthians 1, 16.

- ↑ Romans 15, 22-24.

- ↑ Acts 20, 3.

- ↑ Acts 20, 4-6.

- ↑ Acts 20, 13-14.

- ↑ Acts 20, 17-35.

- ↑ Acts 21, 1-3.

- ↑ Acts 21, 7-8.

- ↑ Acts 21, 17-25.

- ↑ Acts 23, 6-10.

- ↑ Acts 23:23-33.

- ↑ Acts 24, 22-27.

- ↑ Acts 27, 1 - 28, 16.

- ↑ Acts 1, 8.

- ↑ Romans 16:1

- ↑ Romans 16:7

- ↑ 1 Corinthians 14, 34

- ↑ "There is neither Jew nor Greek; there is neither slave nor free; there is no man or woman; for you are all one in Christ Jesus" (cf.Galatians 3, 28)

- ↑ 1 Thessalonians 2, 19-20.

- ↑ Philippians 1, 8.