Paul Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (Paris, June 7, 1848-Atuona, Marquesas Islands, May 8, 1903), known as Paul Gauguin, was a painter recognized Post-Impressionist after his death. His experimental use of color and his synthesist style were key elements in distinguishing him from Impressionism. His work was of great influence on the French avant-garde and many other modern artists, such as Pablo Picasso and Henri Matisse. Gauguin's art became popular after his death, partly due to the efforts of art dealer Ambroise Vollard, who organized late-career and posthumous exhibitions of his work in Paris. Many of his works were in possession of the Russian collector Sergei Shchukin, as well as in other important collections.

Gauguin was an important figure of symbolism, participating as a painter, writer and sculptor of engravings and ceramics. It was his bold experimentation with color that laid the foundation for the synthesist style of modern art, while his expression of the inherent meaning of subject matter in his paintings, under the influence of cloisonnism, paved the way for primitivism and the return to pastoral style (nature capture, landscapes). His work was also a great influence for the use of techniques such as wood engraving and xylography in the realization of works of art. His work helped the evolution of painting, referring to German expressionism and Fauvism (a movement that takes place between 1898 and 1908).

He was Leader of ranks of the Pont-Aven School and inspirer of the Nabis. He developed the most distinctive part of his production in the Caribbean (Martinique) and Oceania (French Polynesia), focusing mostly on landscapes and nudes that were very audacious for their time, due to their rusticity and strong colouring, opposed to the predominant bourgeois and aesthetic painting in his time in western culture. His work is considered among the most important French painters of the 19th century, and he made a decisive contribution to the modern art of the 20th century .

Van Gogh spoke about his Martinique paintings, saying:

Formidable! They were not painted with the brush, but with the phallus. Paintings that are, at the same time, art and sin [...] This is paint that comes out of the guts, from the blood, like sperm comes out of the sex.

Biography

Early Years

Gauguin was born in Paris, France. Son of the anti-monarchist journalist Clovis Gauguin and Alina María Chazal, daughter of the socialist and feminist Flora Tristán, whose father was part of an influential family in Peru. Some versions hold that Simón Bolívar was the father of Flora Tristán, and therefore Gauguin's possible biological great-grandfather. In 1850 the family left Paris and went to Peru, motivated by the political climate of the period (after the coup d'état by Napoleon III). His father Clovis died during the voyage, leaving an 18-month-old Paul, his mother, and his sister to fend for themselves. They lived in Lima for five years with Paul's uncle and his family. The images of Peru would end up being a great influence on Gauguin's art. It was in Lima where Gauguin developed his early childhood and received the stimuli of his Lima environment. His mother admired pre-Columbian art, especially ceramics, since she collects pieces of Inca origin. Following his fascination with ancient Peruvian cultures, Gauguin would come to use the image of a Peruvian mummy in more than twenty of his works.

Gauguin's first memories were how his mother used Lima's traditional dress, an eye that spied behind her manteauThe mysterious veil of one eye that used all the women in Lima. [...] He always felt attracted to women with a traditional look. This must have been the first of many of the colorful dresses that would invade your imagination.

At the age of seven, Gauguin and his family returned to France, coming to Orléans to live with his grandfather. The Gauguin family originally hailed from that area and were gardeners, merchants, growers, and greengrocers: Gauguin means "nut grower." His father broke with family tradition by becoming a journalist in Paris. Gauguin soon learned French, however his main and preferred language continued to be Spanish.

Education and first job

After attending a couple of local schools, Gauguin was sent to the prestigious Petit Séminaire Catholic boarding school at La Chapelle-Saint-Mesmin. He spent three years at that school. At the age of fourteen, he entered the Loriol institute in Paris, a naval preparatory school, before returning to Orléans to take his final year at the Lyceé Jeanne D'Arc. Gauguin registered as a pilot's assistant in the merchant navy. Three years later, he joined the French navy in which he served for two years. His mother died on July 7, 1867, but he did not find out until several months later, when he received a letter from his sister while in India. Marie.

In 1871, Gauguin returned to Paris where he got a job as a stockbroker. His mother's wealthy boyfriend, Gustave Arosa, gave him a job at the Paris Stock Exchange; this when Gauguin was 23 years old. He became a very successful Parisian businessman and remained so for the next 11 years. In 1879 he was earning 30,000 francs a year (about US$125,000 in 2008) as a stockbroker, and twice as much when doing business in the art market.In 1882, the Paris Stock Exchange collapsed and the art market collapsed. art contracted. Gauguin's earnings deteriorated severely, leading him to devote himself to painting full-time.

Marriage

In 1873, he married the Danish Mette-Sophie Gad (1850-1920). Over the next ten years they had five children: Émile (1874-1955), Aline (1877-1900), Clovis (1879-1900), Jean René (1881-1961), and Paul-Rollon (1883-1961). By 1884, Gauguin moved with his family to Copenhagen, Denmark, where he sought a career as a tent seller. It was not a success: he could not speak Danish, and the Danes did not want French canvases. So Mette became the breadwinner of the household, giving French lessons to apprentice diplomats.

His middle-class family and marriage fell apart after 11 years when Gauguin felt the urge to paint full-time. Gauguin returned to Paris in 1885, after being asked to leave by Mette-Sophie and her family for having renounced previously shared values, Gauguin's last physical contact with them was in 1891. Mette finally formalized the separation in 1894.

Early paintings

In 1873, around the same time as his beginnings as a stockbroker, Gauguin began painting in his spare time. His Parisian life was centered in the 9th arrondissement of Paris. Gauguin lived at 15 Rue Bruyère. Around the area were the cafes frequented by the Impressionists. Gauguin used to visit galleries and buy work by emerging artists. He formed a friendship with Pissarro and would visit him on Sundays to paint in his garden. Pissarro introduced him to other artists. In 1877 Gauguin "moved near the market and across the river which led to the poor and recent urban tracts" from Vaugirard (15th arrondissement of Paris). There, on the third floor of 8 Calle Cárcel, he had his first home with a studio, his close friend Émile Schuffenecker, with a story similar to his (a former stockbroker aspiring to become an artist) and Gauguin lived nearby. Gauguin showed paintings at the Impressionist exhibitions held in 1881 and 1882, (previously the sculpture of his son Émile, was for a time the only sculpture in the 4th Impressionist Exhibition of 1879). His paintings received derogatory reviews. Today works such as Vaugirard's Orchards are highly valued.

In 1882, the stock market crashed and the art market contracted. Paul Durand-Ruel, the leading dealer in Impressionist art, was especially hard hit by the crash and stopped buying paintings by artists such as Gauguin. Gauguin's earnings dwindled considerably and over the next two years he slowly formulated his plans to become a full-time artist.The next two summers he painted with Pissarro and occasionally with Paul Cézanne. In October 1883, Gauguin wrote to Pissarro saying that he had decided to make a living by painting "at all costs"; and he asked for his help in achieving it, which, at first, Pissarro gladly accepted. The following January, Gauguin moved his family to Rouen, where he thought, because of his summer stay with Pissarro, he might find important opportunities. However, the venture proved to be unsuccessful, and by the end of the year Mette returned to Copenhagen. Gauguin followed them in November 1884, taking with him his art collection that would remain in Copenhagen.

France 1885-1886

Gauguin returned to Paris in June 1885, accompanied by his six-year-old son Clovis. The other children stayed with Mette in Copenhagen, where they had the support of family and friends, while Mette found work as a translator and French teacher. Gauguin initially found reintegration into the art world in Paris difficult and spent his first winter back in serious poverty, forced to take menial jobs. Eventually Clovis fell ill and was sent to boarding school, Gauguin's sister Marie provided the means to get him in. During his first year he produced very little art. He exhibited 19 paintings and a wood relief at the eighth (and last) Impressionist exhibition in May 1886. Most of these paintings were early work done in Rouen or Copenhagen and were generally nothing new, although his work Baigneuses à Dieppe (Bathers in Dieppe) introduced what would become a recurring theme, the woman in the waves. Felix Bracquemond bought one of his paintings. The exhibition established Georges Seurat as the leader of the avant-garde movement in Paris. Gauguin contemptuously rejected Seurat's pointillist neo-impressionist technique. Later that same year, Gauguin parted ways with Pissarro, who would from then on become an antagonist to Gauguin.

Gauguin spent the summer of 1886 in the artists' colony Pont-Aven in Brittany. He was attracted to the idea because it was an affordable place to live. However, he found unexpected success living with the young art students who came in the summer. His pugilistic nature and temperament (he was a talented boxer and fencer) were not impediments to his living in that socially relaxed environment by the sea. Gauguin was remembered during that period as much for his extravagant appearance as for his artistry. Among the new partners was Charles Laval, who accompanied Gauguin the following year to Panama and Martinique.

That summer he made some pastel drawings of nude figures similar to the method of Pissarro and Degas, exhibited at the eighth impressionist exhibition in 1886. He mainly painted landscapes such as his work La Bergère Bretonne ("The Breton Shepherdess"), in which the figure plays a subordinate role. His work Jeunes Bretons au bain ("Young Bretons Bathing"), introducing a theme to which he returned each time he visited Pont-Aven, is clearly indebted to Degas in terms of its design and bold use of pure color. The innocent drawings of the English illustrator Randolph Caldecott, which used to illustrate a popular guidebook in Brittany, had captured the imagination of avant-garde art students at Pont-Aven, eager to break free from the conservatism of their academies, and Gauguin consciously imitated them in his sketches of Breton women. Those sketches were later turned into paintings when he returned to his studio in Paris. The most important of these was the work Four Britons, which clearly marks a departure from his old Impressionist style as well as the incorporation of something close to the innocence of Caldecott's illustration, exaggerating features to the point of to scratch with the caricature.

Gauguin, along with Émile Bernard, Charles Laval, Émile Schuffenecker and many others, returned to Pont-Aven after their trips to Panama and Martinique. The bold use of pure color and the symbolist choice of subject matter are what distinguishes what is known today as the Pont-Aven School. Disappointed with Impressionism, Gauguin felt that traditional European painting had become too repetitive and imitative and lacked symbolic breadth. In contrast, the art of Africa and Asia seemed to him full of mystical symbolism and vigor. There was a fashion in Europe during that time to appreciate the art of other cultures, specifically that of Japan (Japonism). He was invited to participate in the exhibition dedicated to his work organized by Les XX in 1889.

Cloisonnism and synthesis

Influenced by Japanese folk art and prints, Gauguin's work evolved into Cloisonnism, a style named by critic Édouard Dujardin in response to Émile Bernard's method of painting with flat areas of color and raised edges, which reminded him of Dujardin of the medieval cloisonné technique of enamelling. Gauguin highly appreciated Bernard's art and also his daring in using a style that suited Gauguin in his quest to express the essence of objects in his art. In the work The Yellow Christ (1889), commonly regarded as the quintessential Cloisonnist work, the image was reduced to areas of pure color separated by bold black borders. In such works Gauguin paid little attention to classical perspective and boldly eliminated subtle color gradations, thereby dispensing with the two most characteristic principles of post-Renaissance painting. His painting after him evolved towards Synthetism in which neither shape nor color predominate but each has an equivalent role.

Martinique

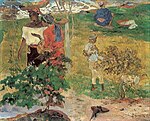

In 1887, after visiting Panama, Gauguin spent several months near Saint Pierre in Martinique, accompanied by his artist friend Charles Laval. Paul Gauguin spent approximately the next 6 months on the island of Martinique from June to November 1887. His thoughts and experiences are recorded in his letters to his wife Mette and their artist friend Emile Schuffenecker. He arrived in Martinique via Panama where he found himself bankrupt and jobless. At the time, France had a right of return policy, which stated that if a citizen found himself bankrupt or stranded in a French colony, the state would pay for a return boat trip. Leaving Panama and being protected by this policy, Gauguin and Laval decided to get off the boat at Martinique's St. Pierre port. Scholars dispute whether it was intentional or spontaneous in deciding to stay on the island. At first, the humble hut they lived in was enough for them and he enjoyed watching people going about their daily activities. However, the weather in the summer was hot and the hut leaked when it rained. Gauguin also suffered from dysentery and malaria. During his stay in Martinique, he produced approximately 10-20 works (12 being the most common estimate), traveled widely, and may have made contact with a community of Hindu immigrants; a contact that would come to influence his art through the incorporation of symbols from India. During his stay, the writer Lafcadio Hearn was also on the island, and his stories are used as a historical comparison to accompany Gauguin's images.

Gauguin completed 11 known paintings during his stay in Martinique, many of which appear to have been developed in his hut. His letters to Schuffenecker express emotion at the exotic location and the natives depicted in his paintings. Gauguin claimed that four of his paintings of the island were better than the rest.The works themselves were brightly colored, lightly painted, and depicted figures from scenes outside. Although his time on the island was short, it is certain that he was a great influence. He recycled some of his figures and sketches of him in subsequent paintings, such as the theme in The Mango Harvest that is reproduced on his fans. Rural and indigenous populations remained a popular theme in Gauguin's works even after his departure from the island.

Gauguin and Van Gogh

Gauguin's Martinique paintings were exhibited in the gallery of his art dealer Arsène Poitier. They were seen and admired by Vincent van Gogh and his own art dealer and brother Theo van Gogh, whose company Goupil & Cie did business with Poitier. Theo bought three of Gauguin's paintings for 900 francs and arranged for them to be hung in Goupil's offices, thus introducing Gauguin to wealthy clients. At the same time Vincent and Gauguin became close friends (on van Gogh's part it was almost flattery) and worked together on art, a collaboration that was essential in Gauguin's ability to formulate his philosophy of art. The arrangement with Goupil continued even after Theo's death in January 1891.

But Gauguin's relationship with van Gogh became strained. In 1888, at Theo's instigation, Gauguin and Vincent spent nine weeks painting together at La Casa Amarilla de Vincent in Arles. Their relationship deteriorated rapidly and Gauguin finally decided to leave. On the night of December 23, 1888 according to a future account by Gauguin, Van Gogh confronted Gauguin with a razor. Later that night, Van Gogh cut off his left ear. He wrapped the severed appendage in a sheet of newspaper and gave it to a prostitute named Rachel, asking her to "keep it safe." Van Gogh was hospitalized the next day and Gauguin left Arles. They never saw each other again, but they continued to correspond and in 1890 Gauguin even went so far as to ask her to set up an art studio together in Antwerp. A sculpted self-portrait of early 1889, the Jug in the form of a head, seems to refer to the traumatic separation of Gauguin and Van Gogh. According to German academics Hans Kaufmann and Rita Wildegans in a BBC report published in 2009, Van Gogh did not cut off his ear, but part of his left lobe. He also did not cut it himself, but Gauguin cut it off with a sword during a dispute.

Gauguin later claimed to have been a major influence on Van Gogh's development as a painter in Arles. Although Van Gogh did experiment a bit with Gauguin's theory of painting from the imagination, present in some paintings of the time such as Memory of the Garden in Etten, this was not comfortable or ideal for him, so he he quickly returned to painting from nature.

Gauguin and Degas

Although Gauguin made his first advances in the art world under the style of Pissarro, Edgar Degas was his most admired contemporary artist and was a great influence on his works from the beginning, with his figures and interiors as well as his recordings and Valérie Roumi's painted medallion. He had great respect for Degas's artistic tact and dignity. It was Gauguin's longest and healthiest friendship, lasting his entire artistic career until his death.

Aside from being an early supporter, including buying Gauguin's works and persuading dealer Paul Durand-Ruel to do the same, there was never such strong public support for Gauguin as Degas. Gauguin also bought works by Degas in the early 1870s and his own predilection for monotype recording was probably influenced by Degas's advances in that medium. Durand-Ruel presented Gauguin with an exhibition in November 1893, which he mainly organized Degas, and received mixed reviews. Some of those who jeered included Claude Monet, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, and his old friend Pissarro. Nevertheless, Degas praised his work, purchasing the work Te faaturuma (The Melancholy) and admiring the exotic lavishness of Gauguin's conjured folklore. As a thank you, Gauguin gave Degas the work The Moon and the Earth, one of the paintings exhibited that attracted the most hostile criticism. The latest version of Gauguin's Riders on the Beach (two versions) is a memory of Degas' images of horses, beginning in the 1860s, specifically the works Hippodrome and Before the Race, being a testament to their lasting effect on Gauguin. Degas later purchases two Gauguin paintings at auction in 1895 to raise funds for his final trip to Tahiti. They were Woman with a Mango and Gauguin's copy of Manet's Olympia.

First visit to Tahiti

By 1890, Gauguin had already considered making Tahiti his next artistic destination. A successful auction of paintings in Paris at the Hôtel Drouot in February 1891, along with other events such as a banquet and a benefit concert, provided the necessary funds. The success of the auction was aided by a favorable review of Octave Mirbeau., who was convinced by Gauguin through Pissarro. After visiting his family in Copenhagen, for what would be the last time, Gauguin set out for Tahiti on April 1, 1891, vowing to return a rich man and start anew. His stated intention was to escape the European civilization and "all that is artificial and conventional". However, he took it upon himself to carry with him a collection of visual stimuli in the form of photographs, drawings and prints.

He spent the first three months in Papeete, the capital of the already heavily Europeanized colony. His biographer Belinda Thomson observes that he must have been disappointed in his vision of a primitive idyll. He was not able to afford the life of pleasures he wanted in Papeete and an early attempt at a portrait, Suzanne Bambridge, was not well liked. He decides to set up his studio in Mataiea, Papeari, about 45 km from Papeete, settling in a native-style bamboo hut. Here he made paintings depicting life in Tahiti as Near the Sea and Ia Orana Maria, the latter of which would become his most valued Tahiti painting.

Many of his most beautiful paintings date from this period. The first portrait of her by a Tahitian model is believed to have been Woman with a Flower. The painting is notable for its careful delineation of Polynesian features. He sent the painting to his patron Gerge-Daniel de Monfreid, a friend of Schuffenecker's who would become Gauguin's greatest devotee in Tahiti, and by the late summer of 1892 it was hanging in the Goupil gallery in Paris. Art historian Nancy Mowll Mathews believes that her encounter with the exotic sensuality of Tahiti, so evident in her paintings, was by far the most important aspect of her stay.

Gauguin was provided with the books Voyage aux îles du Grand Océan by Jacques-Antoine Moerenhout from 1837, and État de la société tahitienne à l'arrivée des Européens by Edmond de Bovis from 1855, which contained detailed accounts of the forgotten culture and religion of Tahiti. He was fascinated by the stories of the Arioi society and their god 'Gold'. Because the stories contained no illustrations, with the Tahitian sitters possibly long since gone, he allowed himself a free exercise of his imagination, executing some 20 paintings and a dozen woodcuts over the course of the next year. The first of these was The Seed of Areoi, depicting Vairaumati, the earthly wife of Oro, now in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. His illustrated notebook Ancien Culte Mahorie is preserved in the Louvre and was published as a facsimile in 1951.

Altogether, Gauguin sent nine of his paintings to Monfreid in Paris. They were eventually displayed in Copenhagen in an exhibition along with works by the late Van Gogh. Reports that they had been well received (although only two of the Tahitian paintings were actually sold, and his early paintings were compared unfavorably with van Gogh's) were enough to encourage him to contemplate returning with another seventy he had completed. He had already exhausted his funds anyway, so he was dependent on financial aid from the state to get a free ticket home. In addition, he had suffered health problems diagnosed as heart problems by the local doctor, who suggested that they may have been early signs of cardiovascular syphilis.

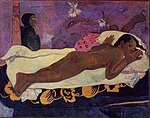

Gauguin wrote a travelogue (published in 1901) entitled Noa Noa, originally intended as a commentary on his paintings and descriptions of his experiences in Tahiti. Modern critics suggest that the book's content was part fantasy and part plagiarism. In it, Gauguin revealed that he had at the time taken a thirteen-year-old girl as his native wife or vahine (Tahitian word for women), a marriage consecrated in the course of an afternoon. Her name was Teha'amana, but he called her Tehura in the travel journal and she turned out to be pregnant by the end of the summer of 1892. Teha'amana was the subject of several of his paintings, including the portrait Merahi metua no Tehamana (The Ancestors of Tehamana) and the renowned Spirit of the Dead Candle, as well as the famous woodcut Tehura now in the Musée d'Orsay.

Return to France

In August 1893, Gauguin returned to France where he continued the execution of paintings with Tahitian themes such as God's Day and Sacred Spring, Sweet Dreams. An exhibition at the Durand-Ruel gallery in November 1894 it was a moderate success, selling eleven of its forty exhibited paintings at high prices. He got himself an apartment at 6 rue Vercingétorix on the edge of the Montparnasse district which was frequented by artists, and thus he began to organize weekly literary salons. He presented himself as an exotic person, wearing Polynesian clothing, and had a public affair with a young woman still in her teens, "half Indian, half Malay," known as "Annah the Javanese".

Despite the moderate success of his November exhibition, he eventually lost Durand-Ruel's patronage due to unclear circumstances. Mathews characterizes it as a tragedy for Gauguin's career. Among other things he missed the opportunity to break into the American market.In early 1894 he was preparing woodcuts using an experimental technique taking subjects from his travelogue Noa Noa . He returned to Pont-Aven for the summer. The following year he tried to organize an auction of his paintings in Paris, similar to the one in 1891, but it was not a success. However, the dealer Ambroise Vollard, showed his paintings in his gallery in March 1895, but unfortunately no agreement was reached on those dates.

He sent a large ceramic sculpture he called Oviri, which he had brought to the hall of the Sociedad Nacional de Bellas Artes the previous winter in April 1895. There are conflicting accounts of how it was received: his biographer and collaborator on Noa Noa and the symbolist poet Charles Morice, argued (1920) that his work was "literally thrown out of the show," while Vollard said (1937) that the work was only admitted when Chaplet threatened to withdraw all of his work as well. In any case, Gauguin took the opportunity to increase his exposure to the public by writing a letter, indignant at the current state of modern ceramics, to Le .

By now it had become clear that he and his wife Mette were definitely separated. Although there were hopes of a reconciliation, they argued very quickly about economic aspects and neither visited the other. Gauguin initially refused to share his legacy of 13,000 francs that his uncle Isidore had inherited shortly after his return. Mette was eventually awarded 1,500 francs, but outraged by this she resolved to communicate with him only through Schuffenecker, so that she could inform even her friends of his betrayal and be humiliated.

Residence in Tahiti

Gauguin again traveled to Tahiti on June 28, 1895. His return is characterized by Thomson as negative, his disillusionment with the art scene in Paris marked by two attacks on him in the same issue of the magazine Mercure de France; one by Émile Bernard and another by Camille Mauclair. Mathews stresses that his isolation in Paris became so bitter that he had no choice but to return to his place in society in Tahiti.

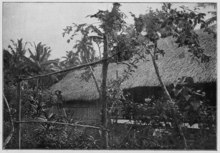

He arrived in September 1895 and would spend the next six years apparently living a comfortable life as a settler artist near, or sometimes within, Papeete. During this time he was able to survive on his own through a growing and steady streak of sales, along with the support of friends and well-wishers, although there was a period between 1898 and 1899 when he felt the need to get a desk job in Papeete, otherwise which there are not many records. He built a shack at Punaauia in an area ten miles east of Papeete, established with an influx of wealthy families, in which he set up a large studio, sparing no expense. Jules Agostini, a Gauguin acquaintance and successful amateur photographer, photographed the house in 1896. A land sale later forced him to build a new one in the same neighborhood.

He kept possession of a horse and carriage, so that he could travel to Papeete to participate in the social life of the colony whenever he wished. He subscribed to the Mercure de France (he became a shareholder), by then the leading French review daily, and maintained an active correspondence with fellow artists, dealers, critics, and patrons in Paris. During this year in Papeete and thereafter, he played an increasing role in local politics, contributing to the local newspaper that opposed the colonial government, Les Guêpes (The Wasps), which had recently formed, and which eventually edited its own monthly publication called La Sonrisa: A Serious Newspaper, later titled An Infamous Newspaper. A certain amount of artistic material and Woodcuts from his newspaper survived. In February 1900 he became the editor of Las Avispas, for which he received a salary and continued as editor until his departure from Tahiti in September 1901. newspaper under his direction was recognized for its crude attacks on the governor and the bureaucracy in general, but Ro was not a leader sympathetic to native causes, although he was perceived that way anyway.

For at least the first year he produced no paintings, informing Monfreid that he would concentrate on sculpture. Very few of his woodcuts from this period survive, most being collected by Monfreid. Thomson states that The Christ on the Cross, a wooden cylinder two feet high, presented a curious mix of religious themes. The cylinder may have been inspired by similar engravings in Brittany, such as at Pleumeur-Bodou, where works by local artisans were Christianized. When he returned to painting, it was to continue his long series of sexually charged nudes in paintings such as Child of God or Never Again. Thomson notes a progression in complexity. Mathews notes a return to Christian symbolism, which would have made him popular with colonialists at the time, but at the time eager to preserve what remained of native culture by emphasizing the universality of principles. religious. In these paintings, Gauguin was addressing the audience of his fellow colonists in Papeete, not his earlier avant-garde audience in Paris.

He suffered from health problems and was hospitalized several times for a variety of ailments. While in France, he broke his heel in a drunken brawl on a visit to Concarneau.The injury, an open fracture, never healed properly. Since then he suffered from sores that appeared on his legs and restricted his movement. He treated them with arsenic. Gauguin blamed the tropical climate and described the sores as & # 34; eczema & # 34;, but his biographers agree that this was a consequence of the progression of syphilis.

In April 1897, he received news that his favorite daughter Aline had tragically died of pneumonia. This was also the month that he found out that she had to leave her house because the land had been sold. He asked for a loan from the bank to build a more extravagant wooden house with beautiful views of the sea and mountains. But he overreached and by the end of the year he was faced with the possibility of being kicked out by the bank.In poor health and in debt, he reached the brink of despair. At the end of the year he completed his great work. Where do we come from? About us? Where Are We Going?, which was recognized as his masterpiece and his last artistic testament (in a letter to Monfreid he explained that he had attempted suicide upon completion). The painting was exhibited at Vollard's gallery in November of the following year., along with eight other paintings with similar subjects that he had completed by July. This was the first major exhibition in Paris since that with Durand-Ruel in 1893 and was a great success, receiving praise for his newfound serenity from the critics. Where We Came From, however, received mixed reviews and Vollard had trouble selling it. He finally did so in 1901 for 2,500 francs (about US$10,000 2000 dollars), to Gabriel Frizeau, a sale for which Vollard possibly received a commission of 500 francs.

Georges Chaudet, Gauguin's dealer in Paris, died in the fall of 1899. Vollard had been buying Gauguin's paintings through Chaudet and then made a deal with Gauguin directly. The deal gave Gauguin a a monthly advance of 300 francs in exchange for the guaranteed purchase of at least 25 of his never-before-seen paintings a year for 200 francs each, plus Vollard made it a point to provide him with art supplies. There were some initial problems for both parties, but Gauguin was finally able to achieve his lifelong dream of living again in the Marquesas Islands in search of an even more primitive society. He spent his last months in Tahiti living in comfort, the freedom with which he spent to entertain his friends at that time being proof of it.

Gauguin was unable to continue his ceramic work on the islands for the simple reason that the required clay was not available. Likewise, without access to a printing press and hectograph, he had to return to the monotype process in his graphic work. Some surviving examples of these prints are rare and expensive to sell.

Gauguin's wife (vahine) during this period was Pahura (Pau'ura) a Tai, the daughter of some neighbors in Punaauia and 14 years old when he took her as his wife. He bore him two sons, of both of whom a daughter died in infancy. The other, a boy, she raised alone. His descendants were still living in Tahiti at the time Mathews's biography was produced. Paa'ura refused to accompany Gauguin to the Marquesas and to be away from his family in Punaauia (she had previously abandoned him when he went to work in Papeete, which is only 10 miles away). When English author Willam Somerset Maugham visited her in 1917, was unable to give her any useful memory of Gauguin, and even chided him for failing to bring money from Gauguin's French family.

Marquesas Islands

Gauguin had planned to live in the Marquesas ever since he saw a collection of engraved Marquesan bowls and weapons when he was in Papeete in the early months of his visit to Tahiti. However, he found a society that, as in Tahiti, had lost their cultural identity. Of all the Pacific island groups, the Marquesas bore the brunt of imported Western diseases (particularly tuberculosis). text-transform:lowercase">XVIII had dwindled to about 4,000. Catholic missionaries prevailed, and in their effort to control alcoholism and promiscuity, forced native children to attend mission schools until adolescence. French colonial rule was enforced by the gendarmerie, famous for its malevolence and stupidity, while merchants, both from the West and China, exploited the natives terribly.

Gauguin settled at Atuona on the island of Hiva-Oa, arriving on September 16, 1901. This was the administrative capital of the island group, but it was considerably less developed than Papeete, although there was an efficient and frequent system of steamboat to travel between the two. There was a military doctor, but no hospital. The doctor moved to Papeete the following February, and since then had to rely on the island's two health workers, Vietnamese adventurer Nguyen Van Cam (Ky Dong), who settled on the island but had no training. formal medical practitioner, and Protestant pastor Paul Vernier, who had studied medicine as well as theology. The two would become good friends.

Gauguin bought a piece of land in the center of town from the Catholic mission, having first won over the local bishop by attending mass regularly. This bishop was Monsignor Joseph Martin, initially content with Gauguin because he knew that he had sided with Catholicism in Tahiti in his journalism.

Gauguin built on his land a house strong enough to survive a cyclone, which wiped out most of the other houses in the town. He was helped in the task by the two best carpenters on the island, one of them named Tioka, tattooed from head to toe in the traditional way of the Marquesas (a tradition interrupted by the missionaries). Tioka was a deacon in the Vernier congregation and became Gauguin's neighbor after the cyclone when Gauguin gave him a corner of his land. The ground floor was in the open air and was used only for dining and living, while the upper floor was used for sleeping and study. The doorway to the upper story was decorated with a carved wood lintel and jambs that would survive later in museums. The lintel named the house as "Maison du Jouir" (House of Pleasure), while the jambs resembled his earlier 1889 work with wood carving called Soyez amoureuses vous serez heureuses (Fall in love, you will be happy). The walls decorated with, among other things, his highly prized collection of 45 pornographic photographs that he bought in Port Said upon his departure from France. At least in the early days, until Gauguin found a vahine (wife), the house attracted crowds of natives at night who came to appreciate it, came to look at the images and celebrate all night. Needless to say, this did not please the bishop, even less when Gauguin placed two sculptures at the foot of the steps satirizing the bishop and his servant girl (supposedly his mistress), least of all when Gauguin attacked the unpopular missionary school system.

State funding for missionary schools ceased as a result of the new 1901 Law of Associations promulgated by the French empire. The schools continued as private institutions but with difficulties, although these were aggravated when Gauguin declared that attendance to any school was only compulsory within a catchment area with a radius of about two to two and a half miles. This led to several teenage daughters being withdrawn from schools (Gauguin called the process 'rescue'). He took one of these girls as a vahine, named Vaeoho (also Marie-Rose), the fourteen-year-old daughter of a native couple who lived in a nearby valley (10 km). This could not to have been very pleasurable for her, due to the grotesqueness and noxiousness of Gauguin's sores at the time, which required daily bandage changes. Nevertheless, she lived with him voluntarily and the following year gave birth to a healthy daughter, whose descendants continue to live on the island.

By November he had settled into his new home with Vaeoho, a cook (Kahui), two other servants (Tioka's nephews), his dog Pegau (a use of his initials PG), and a cat. The house itself, though in the center of town, was nestled amid trees and out of sight. The festivities ended and he began a period of productive work, managing to send 20 canvases to Vollard the following April.He thought he would find new subjects in the Marquesas, writing to Monfreid:

I believe that in the Marquesas, where it is easy to find models (something more and more difficult in Tahiti), and with new landscapes to explore - with new and better wild themes - I can achieve beautiful things. Here my imagination cooled, and also the audience got used to Tahiti. The world is so stupid that if one shows you new canvases with terrible elements, Tahiti would become something understandable and charming. My images of Brittany now are rose water thanks to Tahiti; Tahiti will be perfume thanks to the Marquesas. (Charter) LII a George Daniel de Monfreid, June 1901).Paul Gauguin

In reality, for the most part, his work in the Marquesas can be distinguished from his work in Tahiti only by experts or by their dates, paintings such as Two Women remain of uncertain origin. For Anna Szech, what distinguishes them is their rest and melancholy, although they contain elements of restlessness. Thus, in the second version of Riders on the Beach, which shows clouds and foamy figures, they suggest that a storm is coming, while the distant figures on horseback are similar to other similar figures in other paintings that symbolized death.

Gauguin chose to paint landscapes, still lifes, and figure studies at this time, always with an eye to Vollard's clientele, thus avoiding the themes of the primitive and lost paradises of his Tahitian paintings. But there is a significant trio of paintings from his past period that suggest deeper concerns. The first two are Jeune fille à l'éventail (Girl with a Fan) and Le Sorcier d'Hiva Oa (Marquesan Man in Red Cloak). The model for Girl with a Fan was the red-haired Tohotaua, the daughter of a cacique on the neighboring island. The portrait appears to have been taken from a photograph that Vernier sent to Vollard. The model for the second painting may have been Haapuani, a successful dancer as well as a feared sorceress, who was a friend of Gauguin's and, according to Danielsson, was married to Tohotaua. Szech denotes that the white color of Tototaua's dress is a symbol of power and death in Polynesian culture. Le Sorcier seems to have been made at the same time and shows a long-haired woman wearing an exotic red cape. The androgynous nature of the image attracted attention, confirming speculation that Gauguin intended to depict a person with a third gender. The third painting is the mysterious and beautiful Contes barbares (Primitive Tales) showing a Tohotaua again on the right. The figure on the left is Jacob Meyer de Haan, a painter friend of Gauguin's from the Pont-Aven days who died years ago, while the middle figure is again androgynous, identified by some as Haapuani. The Buddha-like pose and blooming lotus suggest to Elizabeth Childs that the image is a meditation on the perpetual cycle of life and the possibility of rebirth. How these paintings came to Vollard after Gauguin's sudden death, nothing is known. about their intentions in carrying them out.

In March 1902, the governor of French Polynesia, Édouard Petit, arrived in the Marquesas for an inspection. He was joined by Édouard Charlier as head of the judicial system. Charlier was an amateur painter who was a friend of Gauguin's when he became a magistrate in Papeete in 1895. However, their relationship turned into one of enmity when Charlier refused to prosecute Gauguin's then vahine, Pau& #39;ura, for a number of trivial offences, such as alleged burglary and robbery, which he committed in Punaauia while Gauguin was working in Papeete. Gauguin went so far as to publish an open letter to Charlier about the matter in Les Guêpes. Petit, presumably given advance notice, refused to see Gauguin for the delivery of the villagers' protests (Gauguin was his spokesman) about the unfair tax system, which saw its greatest profit from spending in Papeete. Gauguin responded in April by refusing to pay his taxes and encouraging townspeople, merchants and farmers to do the same.

Around that time, Gauguin's health began to deteriorate again, feeling the same symptoms as pain in his legs, heart palpitations and general weakness. The pain in his ankle became unbearable and in July he was forced to order a carriage from Papeete to get around town.By September the pain was so extreme that he had to use morphine injections. However, he became concerned about his new habit of lending his set of syringes to the neighbor, so he switched to laudanum. His eyesight was beginning to fail, as evidenced by the glasses he wore in his last self-portrait. In fact, such a portrait was started by his friend Ky Dong and later finished by Gauguin himself, thus explaining the uncharacteristic style seen in him. It shows an old and tired man, but not yet defeated. For a time he considered the return to Europe, to Spain, to receive treatment. Monfreid advised him:

When you return, you will risk damaging that process of incubation of public appreciation to you, which is in action right now. Now you are a legendary and unique artist, who sends us unthinking and inimitable works of the remote seas of being, which with the definitive creations of a great man who, in some way, has already left this world. Your enemies - and like all those who trouble the mediocres you have many enemies - are silent; but they do not dare to attack you, not even think about it. You're too far away. You shouldn't come back... You are already as inexpugnable as all the great dead; you already belong to the "history of art". - George Daniel Monfreid, Letter to Paul Gauguin about October 1902

In July 1902, Vaeoho, by then seven months pregnant, left Gauguin to return home to the Hekeani Valley to have her baby among her family and friends. She gave birth the following September, but did not return. Gauguin no longer took another vahine. It was around this time that his quarrel with Bishop Martin over missionary schools reached its peak. Local policeman Désiré Charpillet, initially friendly with Gauguin, wrote a report to the island group administrator, who resided on the neighboring island of Nuku Hiva, criticizing Gauguin for encouraging the natives to withdraw their children from school. as well as to encourage the inhabitants not to pay their taxes. Luckily the post of administrator had recently been filled by François Picquenot, an old friend of Gauguin's from Tahiti and essentially sympathetic to him. Picquenot advised Charpillet not to do anything about the school problem, since Gauguin had the law on his side, but he did authorize Charpillet to seize Gauguin's assets as payment for taxes if it came to the worst instances.. Possibly due to his loneliness, and sometimes his inability to paint, Gauguin turned to writing.

In 1901, the Noa Noa manuscript that Gauguin prepared along with his period woodcuts in France, was finally published with Morice's poems in book format in the La Plume edition. (the manuscript itself is now in the Louvre museum). Some sections (including his account of Teha'amana) had been published earlier but without the engravings in 1897 in La Revue Blanche, while Gauguin himself published excerpts in Les Guêpes while I was an editor. The La Plume edition was planned to include the etchings, but he withdrew his permission to print them on plain paper as the publishers wanted. He had actually lost interest in the affair with Morice and never saw a print, refusing an offer of one hundred complimentary copies. However, its publication inspired him to consider writing other books. Early in the year (1902), he revised an old manuscript from 1896-97 called L'Esprit Moderne et le Catholicisme (The Modern Spirit and Catholicism) about the Catholic Church, adding some twenty pages containing accounts of his dealings with Bishop Martin. He sent this text to Bishop Martin, who responded by sending him an illustrated history of the Church. Gauguin returned the book with critical remarks, which he later published in his autobiographical memoirs. He then prepared a witty and well-researched essay called Racontars de Rapin (Tales of an Amateur) about critics and criticism of the art, which he sent for publication to André Fontainas, an art critic at Mercure de France who had a favorable review for Where Do We Come From? About us? Where we go? that he accomplished enough to restore his reputation. However, Fontainas replied that he would not dare to publish it. It would not be published until 1951.

On May 27 of that year, the steamboat service Croix du Sud suffered an accident near Apataki and for a period of three months the island had no mail or supplies. When the mail service returned, Gauguin attacked Governor Petit in a letter, complaining among other things about the way in which they were abandoned after the shipwreck. The letter was published by L'Indepéndant, the successor newspaper to Les Guêpes, in Papeete that November. Petit had in fact pursued an independent and pro- the natives, to the disappointment of the Catholic party, and the newspaper was preparing to attack him. Gauguin also sent the letter to Mercure de France, which published a redacted version of it after his death. He followed up with a private letter to the head of the gendarmerie in Papeete, complaining that his local gendarme Charpillet went to great lengths to make his prisoners work for him. Danielsson explains that while these and similar complaints were substantiated, the motivation for them was wounded vanity and sheer animosity. As it happened, Charpillet was replaced that December by another gendarme named Jean-Paul Claverie from Tahiti, less friendly to Gauguin because he had in fact fined him on his stay in Mataiea for finding him skinny dipping in a local river.

Her health deteriorated further in December to the point that she was barely able to paint. He began an autobiographical memoir called Before and After (published in US translation as Intimate Journals), which he completed over the course of two months. The title was to reflect his experiences. before and after her arrival in Tahiti and as a tribute to her grandmother's unpublished memoirs called Past and Future. Her memoirs were a fragmented collection of observations of her life in Polynesia, her own life, and comments on literature and painting. He included in them themes of attacks such as that of the local gendarmerie, Bishop Martin, his wife Mette and the Danes in general, and ended it with a description of his personal philosophy conceiving life as an existential struggle to unite opposite poles. Mathews makes two final remarks to his philosophy:

No one is good; no one is evil; all are both, in the same way and in different ways...It is so small, the life of a man, and yet there is time to accomplish great things, fragments of the common task.

He sent the manuscript to Fontainas for editing, but the rights passed to Mette on Gauguin's death and it was not published until 1918, with an English translation in 1921.

At the beginning of 1903, Gauguin became involved in a campaign to expose the incompetence of the island's gendarme, Jean-paul Claveria, taking the side of the natives directly in a case involving the alleged drunkenness of a group of them. Nevertheless, Claverie escaped censorship. In early February, Gauguin wrote to the administrator Picquenot, alleging corruption on the part of one of Claverie's subordinates. Picquenot investigated the allegations but was unable to prove them. Claverie responded by charging Gauguin with libel, who was fined 500 francs and sentenced to three months in prison by the local magistrate on March 27, 1903. Gauguin immediately appealed in Papeete and set out to raise the funds to travel to Papeete to attend to your appeal. However, he died unexpectedly on the morning of May 8, 1903, of a suspected heart attack before he could hear the outcome of his appeal. He was buried the next day in the local Catholic cemetery.

Death

Gauguin spent the weeks after being convicted of libel by the gendarme preparing his appeal. During this period he was very weak and in great pain. He resorted again to using morphine. He died suddenly on the morning of May 8, 1903. Previously he had summoned his pastor Paul Vernier, as he had been suffering from fainting spells. They talked together for a while and Vernier left, considering that he was in good condition. However, Gauguin's neighbor, Tioka, found him dead at 11 a.m., confirming the fact by practicing a Marquesan tradition in which someone's head is bitten off in an attempt to revive them. At his bedside was a bottle of laudanum, which has led to speculation that he overdosed, Vernier believed he died of a heart attack.

Gauguin was laid to rest at Clavary Catholic Cemetery (Cimetière Calvaire), on Atuona Hiva 'Oa, at 2 p.m. m. the next day. In 1973, a bronze statue of his work Oviri was placed on his grave, as he indicated it as a wish. Ironically his nearest neighbor in the cemetery is Bishop Martin, with a large cross white on his grave. Vernier wrote an account of Gauguin's last days and his funeral, reproduced in the O'Brien edition of Gauguin's letters to Monfreid.

News of Gauguin's death did not reach France (to Monfreid) until August 23, 1903. In the absence of a will, his less valuable possessions were auctioned off at Atuona, while his letters, manuscripts, and paintings were auctioned at Papeete on September 5, 1903. Mathews notes that this rapid dispersal of his assets led to the loss of much valuable information about his later years. Thomson notes that the auction inventory of his assets (some of which were considered pornography) revealed a life that was not as impoverished or primitive as he would have liked to maintain. In due course Mette Gauguin received the auction proceeds, some 4,000 francs.. One of the paintings auctioned in Papeete was Maternity II, a smaller version of Maternity I that is in the Hermitage Museum. The original was painted in the period when her vahine was Pau'ura in Punaauia, when she gave birth to her son Emile. It is not known why she painted the smaller copy. It was sold for 150 francs to a French naval officer, Commander Cochin, who said Governor Petit had offered as much as 135 francs for the painting. It was sold at Sotheby's for US$39,208,000 in 2004.

The Paul Gauguin Cultural Center in Atuona has a reconstruction of Maison du Jouir. The original house remained empty for a few years, with the door still bearing the lintel carved by Gauguin. This was eventually recovered, four of the five pieces are on display at the Musée d'Orsay and the fifth at the Paul Gauguin Museum in Tahiti.

In 2014, forensic examination of four teeth found in a glass vase in a well near Gauguin's home led to the questioning of the commonly held belief that Gauguin suffered from syphilis. DNA examination established that the teeth were most likely Gauguin's, but there were no traces of mercury (which was used to treat syphilis at the time), thus suggesting that Gauguin did not have syphilis or was not treated for it.

Children

Gauguin outlived three of his children; his favorite daughter Aline who died of pneumonia, his son Clovis who died of a blood infection after hip surgery, and a daughter who had her birth portrayed in an 1896 Gauguin painting called Te tamari no atua (The Birth of Christ), and that she was the daughter of Gauguin's young Tahitian lover, Pau'ura. She died just days after her birth on Christmas 1896. Her son Émile Gauguin worked as a civil engineer in the US and was buried in Lemon Bay Cemetery, Florida. Another son, Jean René, became a renowned sculptor and staunch socialist. He died on April 21, 1961 in Copenhagen. Pola (Paul Rollon) became an artist and art critic and wrote a memoir, My Father, Paul Gauguin (1937). Gauguin had many other children by his lovers: Germaine (b. 1891) with Juliette Huais (1866-1955); Émile Marae a Tau (b. 1899) with Pau'ura; and a daughter (b. 1902) with Mari-Rose. There is speculation that Belgian artist Germaine Chardon was Gauguin's daughter. Emile Marae a Tai, illiterate and raised in Tahiti by Pau'ura, was brought to Chicago in 1963 by French journalist Josette Giraud and was an artist in her own right, her descendants still living in Tahiti as of 2001.

Historical Significance

Primitivism was a painting and sculpture art movement of the late XIX century, characterized by exaggerated body proportions, totem poles, animals, geometric designs and clear contrasts. The first artist to systematically use these effects and achieve wide public success was Paul Gauguin. The European cultural elite who were first discovering the art of Africa, Micronesia, and Native Americans found themselves fascinated, intrigued, and educated by the new, wild and raw power embodied in the art of those far away places. Like Pablo Picasso in the early days of the 20th century, Gauguin was inspired and motivated by the sheer power and simplicity of the call primitive art of those foreign cultures.

Gauguin is also considered a Post-Impressionist painter. His bold, colorful, and design-focused paintings significantly influenced Modern Art. Artists and movements of the early 20th century inspired by him include Vincent van Gogh, Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, André Derain, Fauvism, Cubism and Orphism, among others. He later influenced Arthur Frank Mathews and the American Arts and Crafts Movement.

John Rewald, recognized as the foremost authority on the art of the late 19th century, wrote a series of books on Post-Impressionist period, including Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin (1956) and an essay, Paul Gauguin: Letters to Ambroise Vollard and André Fontainas (included in Rewald's Study in Post-Impressionism, 1986), in which he discusses Gauguin's years in Tahiti and the fight for his survival, seen through correspondence with the art dealer Vollard and others.

Influence on Picasso

Posthumous retrospective exhibitions at the Salon d'Automne in Paris in 1903 and an even larger one in 1906 had a powerful and surprising influence on the French avant-garde and in particular the paintings of Pablo Picasso. In the fall of 1906, Picasso made paintings of large nude women, as well as monumental and sculptural figures that recalled Gauguin's work and showed his interest in primitive art. Picasso's paintings of massive figures in 1906 were directly influenced by Gauguin's sculpture, painting, and writing. The power evoked by Gauguin's work led directly to Les Demoiselles d'Avignon (The Young Ladies of Avignon) in 1907.

According to David Sweetman, Gauguin's biographer, Picasso became a fan of Gauguin's work as early as 1902 when he met and became friends with the Spanish sculptor and ceramicist Paco Durrio (1875-1940) in Paris. Durrio had possession of several Gauguin works because he was a friend of Gauguin's and an unpaid agent of his work. Durrio attempted to help his poverty-stricken friend in Tahiti by furthering his work in Paris. After they met, Durrio introduced Picasso to Gauguin's stonework, helped Picaso make ceramic pieces, and gave Picasso a first edition of La Plume by Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin (Noa Noa: El Diario de Tahiti de Paul Gaugin). As well as seeing Gauguin's work with Durrio, Picasso also saw it at Ambroise Vollard's gallery where both he and Gauguin were represented.

About Gauguin's impact on Picasso, John Richardson wrote,

The 1906 exhibition of Gauguin's work left Picasso as a slave to his art more than ever. Gauguin showed that the most different types of art—not to mention the elements of metaphysics, ethnology, symbolism, the Bible, classical myths and many others—can be combined in a synthesis that was of their time but still eternal. An artist could also confuse conventional notions of beauty, he demonstrated that it is possible, by taking advantage of their demons and taking them to the dark gods (not necessarily Tahiti's) and petting a new source of divine energy. If in future years Picasso paid his debt to Gauguin, it was certainly between 1905 and 1907 when he felt a close relationship with this other Paul, who was proud of Spanish genes inherited from his Peruvian grandmother. If Picasso hadn't signed up as "Paul" in honor of Gauguin.

Both David Sweetman and John Richardson point to Gauguin's sculpture Oviri (meaning savage), the gruesome phallic figure of the Tahitian goddess of life and death that was destined for the tomb of Gauguin and which was exhibited in the retrospective exhibition of 1906, was even more directly what led to Les Demoiselles. Sweetman writes, "Gauguin Oviri's statue, which was shown in 1906, came to stimulate Picasso's interest in sculpture and ceramics, while wood carvings reinforced his interest in engravings, although it was the element of the primitive in everything that most conditioned the direction that Picasso's art would take. This interest would culminate in the seminal Les Demoiselles d'Avignon."

According to Richardson,

Picasso's interest in the gres was even more stimulated by the examples he saw in Gauguin's retrospective in 1906 at Salon d'Automne. The most traumatic ceramic (one that Picasso could have seen with Vollard) was the frightening Oviri. Until 1987 when the Musée d'Orsay acquired this little-known work (exhibited only since 1906) it was never recognized as the masterpiece that is, without saying to be recognized for its relevance in the works that led to Demoiselles. Although it is less than 30 inches high, Oviri it has great presence, as it must be a monument to the tomb of Gauguin. Picasso was hit by Oviri. 50 years later he felt happy when Cooper and I told him that we had found this sculpture in a collection that also had the original plaster of his cubist head. Was it a revelation, like the Iberian sculpture? Picasso shuddered, positively. He always hated admitting the role of Gauguin that led him to primitivism.

Technique and style

Gauguin's initial artistic orientation was with Pissarro, but the relationship left a greater mark personally than stylistically. Gaugin's teachers included Giotto, Raphael, Ingres, Eugène Delacroix, Manet, Degas, and Cézanne. His own beliefs, and in some cases the psychology behind his work, were also influenced by the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer and the poet Stephane Mallarmé.

Gauguin, like his contemporaries such as Degas and Toulouse-Lautrec, employed a technique for painting on canvas known as peinture à l'essence. For this, the oil (binder) is drained from the paint and the pigment residue is mixed with turpentine. He may have used a similar technique when preparing his monotypes, using paper instead of metal, as it would absorb the oil giving the paintings the matte appearance he desired. He also tried some of his existing drawings with the aid of glass, copying a bottom image on the glass surface with watercolor or gouache for printing. Gauguin's woodcuts were no less innovative, even for the avant-garde artists responsible for reviving the woodcut at the time. Rather than engrave his blocks in an attempt to achieve detailed illustration, Gauguin initially chiselled/carved his blocks in a manner similar to wood sculpture, followed by the use of finer tools to create detail and tonality within their bold outlines.. Many of his tools and techniques were considered experimental. This methodology and use of space ran parallel to his painted in flat and decorative reliefs.

Beginning in Martinique, Gauguin began to use proximity in analogous colors to achieve a muted effect. Soon after this he also made advances in non-representational color, creating canvases that had an independent existence and vitality of their own. This gap between surface reality and himself disgusted Pissarro and quickly led to the end of their relationship. His human figures at this time were also a reminder of his love affair with Japanese prints, particularly the innocence of his figures and their compositional austerity, which became an influence on his early manifesto. For that same reason, Gauguin also found himself inspired by folk art. He sought an emotional purity displayed in his subjects, which was conveyed directly, emphasizing large shapes and vertical lines that clearly defined shape and outline. Gauguin also used complex formal decoration and colors in abstract patterns, attempting to provide harmony between man and nature. His depictions of the natives in their natural environments are often evidence of autonomous serenity and sustainability. This alluded to one of Gauguin's favorite themes, which was the intrusion of the supernatural into daily life, in one instance reaching the extreme of depicting ancient Egyptian tomb reliefs with the works Her Name is Vairaumati (Her Name is Vairamauti) and Ta Matete.

In an interview with L'Écho de Paris published on March 15, 1895, Gauguin explains that developing his tactical approach is to achieve synesthesia (in art). He states:

- Each feature of my paintings is carefully considered and calculated in advance. Like in the musical composition, for example. My goal, which I take from everyday life or nature, is merely a pretext, which helps me define a set of lines and colors to create symphonies and harmony. They do not have any counterparts in reality, in the vulgar sense of such a word; they do not give a direct expression of any idea, but their only purpose is to stimulate the imagination--as music does without the help of ideas or images--just with that mysterious affinity that exists between certain arrangements of colors and lines in our minds.

In an 1888 letter to Schuffenecker, Gauguin explains his huge departure from Impressionism, saying he now intended to capture the soul of nature, ancient truths, and the character of its settings and inhabitants. Gauguin wrote:

- Don't copy nature literally. Art is an abstraction. It defuses art from nature while you dream in the presence of nature, and thinks more about the act of creation than the result.

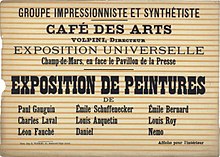

Other media

Gauguin began making etchings in 1889, in addition to a series of works in zincography commissioned by Theo van Gogh, known as the Volpini Suite, which also appeared in the 1889 Café des Arts demonstration Gauguin did not hesitate, even with his inexperience in printing, to choose a number of provocative and unorthodox options, such as zinc plate instead of limestone (lithography), wide margins, and long sheets of yellow flipchart. The result it was vivid to the point of being very gaudy and garish, but it foreshadowed his more complicated experiments with color printing and the attempt to elevate monochrome images. His first print masterpieces were the Noa Noa Suite of 1893-94 where he essentially reinvented the medium of woodcutting, bringing it into the modern era. He began this series shortly after returning from Tahiti, eager to reclaim his leadership position within avant-garde and to share images based on his excursion to French Polynesia. These woodcut prints were shown at his unsuccessful exhibition of Paul Durand-Ruel in 1893, most being directly related to paintings by him in which he recalled the original composition. They were shown again in a minor exhibition at his studio in 1894, where he garnered critical acclaim for his exceptional painting and sculptural effects. Gauguin's new preference for woodcuts was not only a natural extension of his woodcut reliefs and sculpture, but may also have been prompted by his historical importance to medieval and Japanese artisans.

Gauguin began monotype with watercolors in 1894, possibly overlapping with his Noa Noa woodcuts, perhaps even serving as a source of inspiration for them. His techniques remained innovative and it was a suitable medium for him as it did not require complex equipment, as well as in the printing process. Despite frequently being a source of practice for his associated paintings, sculptures or prints, his innovation in the monotype offers an ethereal aesthetic; ghostly images that can express his desire to convey the immemorial truths of nature. The next major project of his was a monotype and woodcut that carried through to 1898-99, known as the Vollard Suite. He completed his initiative series of 475 prints of some twenty different compositions and sent them to dealer Ambroise Vollard, despite not committing to his request for a steady job. Vollard was not satisfied and made no effort to sell them. Gauguin's series is clearly tied to the black and white aesthetic, and he may have intended the prints to be similar to the myriorama card set, in that they could have been arranged in any order to create multiple panoramic landscapes. The activity of arranging and rearranging was similar to his own process of repurposing (repurposing) his images and subjects, as well as a tendency toward symbolism. He made prints on tissue-thin Japanese paper and multiple proofs of gray and black could be arranged one on top of the other, with each color transparency showing through to produce a rich, chiaroscuro effect.

In 1889 he began his radical experiment: oil/oil transfer drawings. Like his watercolor monotype technique, it was a mix between drawing and engraving. The transfers were the grand culmination of his quest to find an aesthetic of primary purpose, which seems to be conveyed in his results that reflect ancient carvings, weathered frescoes, and cave paintings. Gauguin's technical progress from monotype to oil transfers is quite remarkable, progressing from small sketches to painstakingly large, quality sheets. With these transfers he created depth and texture by printing multiple layers on the same sheet, starting with graphite pencil and black ink for outlining, before moving to blue crayon to reinforce lines and add shading. He often completed the image with an olive or coffee ink wash, from which he had oiled. The practice consumed Gauguin until his death, fueling his imagination and conceiving new themes for his paintings. This collection was also sent to Vollard who was never surprised. Gauguin appreciated oil transfers for the way they transformed the quality of the drawn line. His process, almost similar to alchemy, had elements of chance whereby unexpected marks and textures regularly emerged, something that fascinated him. In the metamorphosis from a drawing to a painting, Gauguin made the calculated decision to give up legibility in order to gain mystery and abstraction.

He worked on wood throughout his career, particularly during his most prolific periods, and is known for achieving radical results in engraving before turning to painting. Even in early exhibitions of him, Gauguin used to include wooden sculptures in his shows, on which he built his reputation as a connoisseur of the so-called primitive. A number of his early recordings appear to have been influenced by Gothic and Egyptian art.In his correspondence, he also notes a passion for Cambodian art and the masterful color of Persian rugs and oriental rugs.

Legacy

The fashion for Gauguin's work began shortly after his death. Many of his more recent paintings were acquired by the Russian Sergei Shchukin collection. A significant part of his collection is displayed in the Pushkin Museum and in the Hermitage. Gauguin's paintings are rarely sold, as their prices reach tens of millions of dollars. His 1892 work When Are You Married? it became the most expensive work of art in the world when its owner, the family of Rudolf Staechelin, sold it privately for US$300 million in February 2015. It is believed to have been purchased by the Qatar Museums.

- Gauguin's life inspired the novel The Moon and six pennies of W. Somerset Maugham. Mario Vargas Llosa based his novel Paradise in the other corner (2003) in the life of Gauguin, as well as his grandmother Flora Tristan.

- Gauguin is the theme of at least two operas: Federico Elizalde Paul Gauguin (1943); and Gauguin (a synthetic life) by Michael Smetanin and Alison Croggon. Déodat de Séverac wrote his piece; Elegy for piano in memory of Gauguin.

- The biographical film called Oviri (1986) shows his life when he returns to Paris in 1893 after his two-year stay in Tahiti, in addition to his confrontation with his wife, children and a lover. Finish your return to Tahiti two years later.

The Japanese-style Gauguin Museum across from the Papeari Botanical Gardens in Papeari, Tahiti, contains exhibits of original documents, photographs and sketches, as well as Gauguin prints. In 2003 the Paul Gauguin Cultural Center opened its doors in Atuona in the Marquesas Islands.

In 2014 the painting Fruits sur une table ou nature au petit chien (1889), with an estimated value of €10m and €30m (£8.3m to £24.8m), which had been stolen in London in 1970, it was discovered in Italy. The painting, along with a work by Pierre Bonnard, were purchased by a Fiat employee in 1975, at a sale due to property loss from railway construction, for 45,000 lire (about £32).

Works by Gauguin

- The lake on the plain, (1874), Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge

- The Seine at the Jena Bridge, (1875), Museum of Orsay, Paris

- Autumn Landscape, (1877), Collection particular.

- Mette Gauguin sewing(about 1878), Bührle Collection, Zurich

- Garden under snow, (1879), Szépmûvészeti Múzeum, Budapest

- The Hortelans of Vaugirard, (1879), Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts

- Study of a nude or Susanna sewing, (1880), Ny Carlsberg Glypotek, Copenhagen

- Interior of the artist in Paris, Calle Carcel, (1881), Nasjonalgalleriet, Oslo

- Garden in Vaugirard, (1881), Ny Carlsberg Glypotek, Copenhagen

- Ruan, blue roofs, (1884, Private Collection, Winterthur, Switzerland

- Mette Gauguin with evening suit, (1884), Ny Carlsberg Glypotek, Copenhagen

- The vision behind the sermon, (1888), Scottish National Gallery, Edinburgh

- Laundries of Arles (1888), Bilbao Museum of Fine Arts

- The green crysto (1889), [self-collection]

- The yellow ChristOil on canvas of 92 x 73 cm, painted in 1889. It is located at the Albright-Knox[1] Museum of Buffalo (New York).

- The beautiful AngelaOil on canvas of 92 x 73 cm, painted in 1889. It is located at the Museum of Orsay, Paris.

- Tahiti women (on the beach), (1891), Orsay Museum, Paris

- Manao Tupau, (1892)

- Ta Matete (1892), Museum of Orsay, Paris

- Kill Mua (1892), Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza Collection

- I greet you, Mary (Ia orana MariaOil on canvas of 113.7 x 87.7 cm, painted in 1892. It is located at the Metropolitan Museum[2] in New York

- Area, (1892), Museum of Orsay, Paris

- Self-portrait with hat, (1893)

- Bretonous peasants, (1894), Orsay Museum, Paris

- Vairumati (1897), Museum of Orsay, Paris

- Never moreOil on canvas of 68 x 116 cm, painted in 1897. It is located in Courtauld Gallery, London.

- Where do we come from? Where are we going? (1897), Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

- Young with fanOil on canvas of 92 x 73 cm, painted in 1902. It is located in Folkwang Museum[3] in Essen, Germany.

- barbaric counts, (1902), Folkwang Museum, Essen

- Two women or The flowered scalp

Gallery

Self-portraits:

Fonts

- Bowness, Alan (1971), Gauguin. Phaidon Press Limited. ISBN 0 7148 1481 4.

- Blackburn, Henry (1880). Breton Folk: An Artistic Tour in Brittany. Illustrated by Randolph Caldecott. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington.

- Cachin, Françoise (1989, English translation 1992). Gauguin: The Quest for Paradise. Gallimard; English translation by Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0 500 30007 0.

- C. Childs, Elizabeth; Figure, Starr; Foster, Hal; Mosier, Erika (2014). Gauguin: Metamorphosis. Museum of Modern Art. ISBN 978 0 87070 905 0.

- Childs, Elizabeth C. (6 October 2011). «Chapter 6: Remixing Paradise - Gauguin and the Marquesas Islands». In Greub, Suzanne, ed. Gauguin and Polynesia. Hirmer Verlag. pp. 306-321. ISBN 978-3777442617.

- Danielsson, Bengt (1965). Gauguin in the South Seas. New York: Doubleday and Company.

- Danielsson, Bengt (1969). The Exotic Sources of Gauguin's Art.

- Eisenman, Stephen F., (1999). Gauguin's Skirt. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28038-6.

- Field, Richard S. (1973). Paul Gauguin: Monotypes. Philadelphia Museum of Art (Lebanon Valley). LCCN 73077306.

- Frèches-Thory, Claire (1988). «The Return to France». The Art of Paul Gauguin. with Peter Zegers. National Gallery of Art. pp. 369-73. ISBN 0-8212-1723-2. LCCN 88081005.

- Goddard, Linda (2008). «'The Writings of a Savage?' Literary Strategies in Paul Gauguin's "Noa Noa"». Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes (Warburg Institute) 71: 277-293.

- Gauguin, Paul; Morice, Charles (1901). Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin.

- Gauguin, Paul (2011) [1921]. Paul Gauguin's Intimate Journals. Translated by Van Wyck Brooks. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486294414.

- Gauguin, Paul. The letters of Paul Gauguin to Georges Daniel de Monfreid, translated by Ruth Pielkovo; foreword by Frederick O'Brien. archive.org

- Gayford, Martin (2006), The Yellow House: Van Gogh, Gauguin, and Nine Turbulent Weeks in Arles, London: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-670-91497-5.

- Mathews, Nancy Mowll (2001). Paul Gauguin, an Erotic Life. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press, ISBN 0-300-09109-5.

- Perruchot, Henri (1961). La Vie de Gauguin (in French). Hachette.

- Rewald, John (1986). Studies in Post-Impressionism. Harry N. Abrams Inc.

- Richardson, John (1991). A Life Of Picasso, The Cubist Rebel 1907–1916. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-307-26665-1.

- Solomon-Godeau, Abigail. Going Native, Paul Gauguin and the Invention of the Primitivist Modernist. The Expanding Discourse: Feminism and Art History. 1st ed. Boulder, CO: WestView, 1992. 313-329

- Stuckey, Charles F. (1988). «The First Tahitian Years». The Art of Paul Gauguin. with Peter Zegers. National Gallery of Art. pp. 210-95. ISBN 0-8212-1723-2. LCCN 88081005.

- Sweetman, David (1995). Paul Gauguin, A Life. New York City, New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-80941-9.

- Szech, Anna (15 February 2015). «Marquesas 1901-1903». In Bouvier, Raphaël; Schwander, Martin, eds. Paul Gauguin. Fondation Beyeler (Hatje Cantz). pp. 148-9. ISBN 978-3775739597.

- Thomson, Belinda (1987). Gauguin. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-20220-6.

- F. Walther, Ingo (2006). Paul Gauguin. Taschen. ISBN 978 3 8228 5986 5.

Additional bibliography

- Danielsson, Bengt (1965). Gauguin in the South Seas. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

- Gauguin, Paul; Morice, Charles (1901). Noa Noa: The Tahiti Journal of Paul Gauguin.

- Gauguin, Paul (Brooks, Van Wyck, translator; 1997). Gauguin's Intimate Journals. Mineola, New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-29441-4.

- Pichon, Yann le; translated by I. Mark Paris (1987). Gauguin: Life, Art, Inspiration. New York: Harry N Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-0993-9.

- Rewald, John (1956; revised 1978). History of Post-Impressionism: From Van Gogh to Gauguin, London: Secker & Warburg.

- Rewald, John. (1946) History of Impressionism.

- Vargas Llosa, Mario. Paradise on the other corner. Alfaguara, Madrid, 2003.

Contenido relacionado

The Prisoner of Zenda (1952 film)

Martin Chambi

Tango

![Among the Mangoes (La Cueillette des Fruits) (Entre los Mangos/La cosecha de Mangos), 1887, Museo van Gogh, Ámsterdam[45]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/a8/Paul_Gauguin_087.jpg/150px-Paul_Gauguin_087.jpg)

![Annah the Javanese, (1893), Colección privada[94]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/5/5c/Paul_Gauguin_004.jpg/102px-Paul_Gauguin_004.jpg)

![Cavaliers sur la Plage [II] (Jinetes en la Playa), 1902, Colección privada](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/0/0a/Paul_Gauguin_106.jpg/150px-Paul_Gauguin_106.jpg)