Parasaurolophus

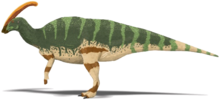

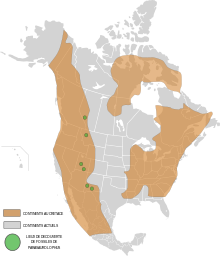

Parasaurolophus (from the Gr. para/παρα "together" or "close", saurus/σαυρος " lizard" and lophos/λοφος "crest" means "Close to the crested lizard") is a genus of hadrosaurid ornithopod dinosaurs, which lived at the end of the Cretaceous period, approximately 76 years ago, 5 to 73 million years ago, in the Campanian, in what is now North America. Its name refers to a supposed relationship with the dinosaur Saurolophus. It was a herbivore that walked both bipedally and quadrupedally. Three species are known, Parasaurolophus walkeri, the type species, Parasaurolophus tubicen and the short-crested Parasaurolophus cyrtocristatus. Its remains have been found in Canada, in the Oldman and Dinosaur Park formations, both part of the Judith River Group in Alberta forP. walkeriand in the United States, being found in New Mexico in the Kirtland Formation, P. tubicen, in the Fruitland Formation, P. cyrtocristatus, in Utah, and the Kaiparowits Formation, P. cyrtocristatus. First described in 1922 by William Parks from a skull found in Alberta.

Parasaurolophus is a hadrosaurid, part of the diverse family of Cretaceous dinosaurs known for their variety of strange head ornaments. This genus is known for its large, elaborate cranial crest, shaped like a tube that projects back and above the skull. Charonosaurus from China, which may be its closest relative, has a very similar skull and a possible similar crest. The crest has been the subject of much discussion among paleontologists, with the current consensus being that its important functions included visual recognition of species and sex, acoustic resonance, and thermoregulation. It is one of the rarest duck-billed dinosaurs, known from only a handful of good specimens.

Description

As is the case with most dinosaurs, the skeleton of Parasaurolophus is not completely known. The body length of the type specimen ofP. walkeriis estimated at 10 meters. The skull measures 1.6 meters long, including the crest, however the skull ofP. tubicen exceeds this in length, indicating an even larger animal. The estimated weight is 2.5 tons. The only known forelimb is relatively short for a hadrosaurid, with a short but wide scapula. The femur measures 103 centimeters inP. walkeriand is robust for its length when compared to that of other hadrosaurids. The humerus and pelvic bones are strongly built.

Like other hadrosaurids, it is possible that it walked on two or four legs. It is likely that it stood on two legs to reach its food, but would move on four. The spinous process of the vertebrae was high, something common in lambeosaurines; higher on the hips, they increased the height of the back. The skin impressions that are known inP. walkeri, show a uniform structure of scales similar to tubercles, but without any special feature.

These animals had long tails flattened at the sides, which leads us to think that Parasaurolophus could swim. The end of the limbs is a mystery, some paleontologists say they are hooves and others say they are claws worn by time. Skin impressions of Parasaurolophus have been found, as well as several complete skeletons so we have a very good idea of what it looks like.

The crest

The most remarkable thing about this dinosaur is the crest, which detaches from the back of the head and was composed of the premaxillary and nasal bones. The type specimen ofP. walkerihas a notch in the dorsal spines of the vertebrae near where the crest would hit the back, but this may be a pathology peculiar to this individual. William Parks, who named the genus, hypothesized that a ligament was located from the crest to the notch to help support the head. Although this idea seems far-fetched, Parasaurolophus is sometimes restored with a sail of skin from the crest to the neck. This was a huge tubular crest with four hollow sections; two that pointed upwards and two downwards long that connected with the nose, which was believed to be able to serve as a tube for breathing underwater, an assumption that was disproved by later studies: which established the absence of some type of hole at the top. Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the function of the crest, although most of them have been discredited. Some of these hypotheses about its crest are, for example: breathing underwater, a theory that was believed for a long time until which was denied. It is believed that it was for the attraction and distinction between males and females, to communicate in case of danger or order and for thermoregulation. The most outstanding is communication. This was carried out by observing the internal structure of the tube, to conclude that it could have functioned as a natural resonator, and have had a sound function.

Based on models made of the crest, it has been suggested that it was used to make sounds (similar to those of a trombone) in order to communicate with dinosaurs of the same species. A function that is also believed to be possible is the attraction of males to females using the crest, this is believed to be due to the fact that males have a longer crest than those of females.

The crest was hollow, with separate tubes running from each nostril to the end of the crest to turn in the opposite direction and head behind and down the crest and skull. The tubes were simpler inP. walkeri, and more complex in P. tubicen, where they were hidden and other tubes crossed and separated. As P. walkeriand P. tubicenhad long ridges with only a slight curvature, P. cyrtocristatushad a short crest with a more circular profile.

Discovery and research

First described in 1922 by William Parks, it is based on ROM 768, a skull and partial skeleton missing most of the tail, the distal hind legs of the patellofemoral joint, which was found by an expedition from the University of Toronto in 1920 near Sand Creek on the banks of the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada. These rocks are today dated to the Campanian, in the Upper Cretaceous, being part of the Dinosaur Park Formation. The name Parasaurolophus, meaning "near crested lizard", is derived from the Greek para, παρα, "next to" or "close", saurus, σαυρος, "lizard" and lophos, λοφος "crest". William Parks named the specimenP. walkeri in honor of Sir Byron Edmund Walker, Chairman of the Board of Trustees of the Royal Ontario Museum. Parasaurolophus remains are rare in Alberta, with only one other skull of an individual juvenile, possibly from this same formation or from the Oldman Formation, and three possible specimens without skulls from the Dinosaur Park Formation. In certain lists of faunas, mention is made of material from P. walkeri in the Hell Creek Formation of Montana, a rock unit dated to the late Maastrichtian. This situation was not taken into account by Sullivan and Williamson in their review of the genus in 1999, and has not been further explored. the topic elsewhere.

In 1921, Charles H. Sternberg recovered a partial skull (PMU.R1250) from the slightly younger Kirtland Formation in San Juan County, New Mexico. This specimen is found in Uppsala, Sweden, where Carl Wiman described it as a second species,P. tubicen, in 1931. The specific epithet comes from the Latin tǔbǐcěn "trumpeter". A second, almost complete skull P. tubicen(NMMNH P-25100) which was found in New Mexico in 1995. Using computed tomography on this skull, Robert Sullivan and Thomas Williamson gave this genus a very comprehensive monograph in 1999, covering aspects of its anatomy and taxonomy., and the functions of its crest. Williamson later published an independent review of the remains, disagreeing with the taxonomic conclusions.

John Ostrom described another good specimen, FMNH P27393, from New Mexico, P. cyrtocristatus in 1961. It includes a partial skull with a short, rounded crest, and much postcranial skeletal material except for the feet, neck, and tail pieces. The specific name derives from the Latin curtus "short" and cristatus "crest". This specimen was found in the Fruitland Formation or, more likely, in the base covering the Kirtland formation. The distribution range of this species is expanded in 1979, when David B. Weishampel and James A. Jensen described a partial skull, cataloged BYU 2467, with a crest of the same type in that of the Kaiparowits formation, in Garfield County, Utah. In addition to this, another skull has been found in Utah with the short and rounded crest ofP. cyrtocristatus.

Species

Parasaurolophus is known from three specific species, P. walkeri, P. tubicenand P. cyrtocristatus. All of them can be distinguished from each other and have many differences. The first named species, therefore the type, is P. walkeri. Reference is made to a certain specimen, from the Dinosaur Park Formation, but it is almost certain that many more are referenceable. The type species P. walkeri, from Alberta, is known from a single well-established specimen. It differs from P. tubicen for having simple tubes in the crest, and from P. cyrtocristatus for having a longer and not so rounded crest and a humerus longer than the radius.

The second named species is P. tubicen, from New Mexico is known from the remains of at least three individuals. This is the largest species, with more complex air passages in the crest than P. walkeriand is larger and less curved than P. cyrtocristatus. Three specimens are known, and they can be differentiated from its other species. It has a long, straight crest, with a very complex interior compared to the other species. All known specimens of Q. tubicencome from the De-Na-Zin Member of the Kirtland Formation.

In 1961, the third species was named P. cyrtocristatus, from New Mexico and Utah, is known from three possible specimens. All three of its known specimens have been found in the Fruitland and Kaiparowits Formations of Utah and New Mexico. The second specimen, the first known from the Kaiparowits Formation, was not originally assigned to a specific taxon. It is the smallest species, with a short, rounded crest. Its small size and the shape of its crest have led several scientists to suggest that it represents young or femaleP. walkerior P. tubicen, although P. tubicen lived approximately a million years later. According to Thomas Williamson, the type matter of P. cyrtocristatus is approximately 72% the size of P. tubicen, close to the size that is interpreted for other lambeosaurines as evidence of sexual dimorphism in their crests, approximately 70% of the adult size. Although many scientists have supported the possible fact that P. cyrtocristatus is a female, many other studies have found that it is not, due to differences in age, distribution and large differences in the crest and its internal structure.

A study published in PLoS ONE in 2014 found that one more species could refer to Parasaurolophus. This study, led by Xing, found that Charonosaurus jiayensis was actually nested deeply within Parasaurolophus, which created the new species P. jiayensis. If this species is within Parasaurolophus, then the genus lasted until the Paleogene Cretaceous extinction, and is known from two continents.

Classification

As its name indicates, Parasaurolophus was initially linked to Saurolophus due to similarities in crest. However, it was quickly assigned to the hadrosaurid subfamily Lambeosaurinae while Saurolophus is considered a Hadrosaurinae. It is usually interpreted separately from other lambeosaurines, distinguishing it from helmet-crested hadrosaurids such as Corythosaurus, Hypacrosaurus and Lambeosaurus. Its closest relative appears to be Charonosaurus, a lambeosaurine with a similar skull, but for which the complete crest is not known, the Amur River region of northeastern China, and the two are placed in the tribe Parasaurolophini. P. cyrtocristatus, with its short, rounded crest, is considered the most phylogenetically basal of the three known species of Parasaurolophus, or it could be a juvenile or female of the species P. tubicen.

Phylogeny

The following cladogram is after the 2007 redescription of Lambeosaurus magnicristatus by Evans and Reisz in 2007.

| Hadrosauridae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleoecology

Alberta

Parasaurolophus walkeri, from the Dinosaur Park Formation, was a member of a diverse and well-documented fauna of prehistoric animals, including well-known dinosaurs such as the ceratopsids Centrosaurus, Chasmosaurus and Styracosaurus, other duckbills such as Gryposaurus and Corythosaurus, the armored ankylosaurians, Edmontonia Euoplocephalus and Dyoplosaurusand the tyrannosaurid Gorgosaurus. It was a rare component of this fauna. The Dinosaur Park Formation is interpreted as a low-relief environment of rivers and floodplains that became more marshy and influenced by marine conditions over time as the Western Interior Seaway transgressed westward. The climate was warmer than today's Alberta, without frost, but with wet and dry seasons. Conifers were apparently the dominant canopy plants with an understory of ferns, tree ferns and angiosperms.

Some of the less common hadrosaurs in the Dinosaur Park Formation of Dinosaur Provincial Park, such as Parasaurolophus, may represent the remains of individuals that died while migrating through the region. They could also have had an upland habitat where they may have nested or fed. The presence of Parasaurolophus and Kritosaurus at northern latitude fossil sites may represent a faunal exchange between otherwise distinct northern and southern biomes in North America. Upper Cretaceous. Both taxa are rare outside the southern biome, where, along with Pentaceratops, they are predominant members of the fauna.

New Mexico

In the Fruitland Formation of New Mexico, P. cyrtocristatusshared its habitat with other ornithischians and theropods. Specifically, its contemporaries were the ceratopsian Pentaceratops sternbergii, the pachycephalosaurid Stegoceras novomexicanum and some unidentified fossils belonging to Tyrannosauridae?, Ornithomimimus?, Troodontidae?, Saurornitholestes langstoni?, Struthiomimus?, Ornithopoda?, Chasmosaurus?, Corythosaurus Hadrosaurinae, Hadrosauridae and Ceratopsidae. When Parasaurolophus existed, the Fruitland Formation was swampy, located in the lowlands and near the coast of the Western Interior Seaway. The lowest part of the Fruitland Formation is less than 75.56 ± 0.41 million years old, and the upper limit dates back to 74.55 ± 0.22 million years old.

Existing slightly later than the Fruitland Formation species, P. tubicen is also found in New Mexico, in the Kirtland Formation. Numerous groups of vertebrates are from this formation, including fish, crurotarsals, saurischian ornithischians, pterosaurs, and turtles. The fish are represented by the two species Melvius chauliodous and Myledalphus bipartitus. Crurotarsals include Brachychampsa montana and Denazinosuchus kirtlandicus. The ornithischians of the formation are represented by the hadrosaurids Anasazisaurus horneri, Naashoibitosaurus ostromi, Kritosaurus navajovius and P. tubicen, the ankylosaurids Ahshislepelta minor and Nodocephalosaurus kirtlandensis, the ceratopsians Pentaceratops sternbergii and Titanoceratops ouranos and the pachycephalosaurids Stegoceras novomexicanum and haerotholus goodwini. The saurischians include the tyrannosaurid Bistahieversor sealeyi and the ornithomimid Ornithomimus sp. and the troodontid " Saurornitholestes " robustus. [48] A pterosaur is known, called Navajodactylus boerei. Turtles are quite abundant and are known from Denazinemys nodosa, Basilemys nobilis, < i>Neurankylus baueri, Plastomenus robustus and Thescelus hemispherica. Dubious taxa are known, including a crurotarsal assigned to Leidyosuchus, and the theropods Struthiomimus, Troodontidae and Tyrannosauridae. The beginning of the Kirtland Formation dates back to 74.55 ± 0.22 million years, and the formation ends around 73.05 ± 0.25 million years.

Utah

Argon-argon radiometric dating indicates that the Kaiparowits Formation was deposited between 76.6 and 74.5 million years ago, during the Campanian stage of the Late Cretaceous. During the late Cretaceous period, the site of the Formation Kaiparowits was located near the western coast of the Western Interior Seaway, a large inland sea that divided North America into two land masses, Laramidia to the west and Appalachia to the east. The plateau where the dinosaurs lived was an ancient floodplain dominated by large canals and abundant peat from wetlands, swamps, ponds and lakes, and was bordered by highlands. The climate was humid and rainy, and supported an abundant and diverse range of organisms. This formation contains one of the best and most continuous records of terrestrial life from the Late Cretaceous in the world.

Parasaurolophus shared its paleoenvironment with other dinosaurs, such as dromaeosaurid theropods, the troodontid Talos sampsoni, ornithomimids such as Ornithomimus velox, tyrannosaurids such as Albertosaurus and Teratophoneus, armored ankylosaurids, hadrosaurid Gryposaurus monumentensis, the ceratopsians Utahceratops gettyi, Nasutoceratops titusi and Kosmoceratops richardsoni and the oviraptorosaurian Hagryphus giganteus. The paleofauna present in the Kaiparowits Formation included chondrichthyans, sharks and rays, frogs, salamanders, turtles, lizards and crocodiles. There were a variety of early mammals, including multituberculates, marsupials, and insectivores.

Paleobiology

Food

Like all hadrosaurids, Parasaurolophus was an animal with the ability to move bipedally or quadrupedally, feeding on herbivores. It had hundreds of teeth arranged in columns that were replaced as they wore out. This wear and tear was due to the fact that it had a sophisticated chewing apparatus that allowed it to grind food before swallowing it, unlike other herbivores of its time. It took food with an organ similar to a beak and was kept inside the mouth by structures similar to the cheeks of mammals, which prevented the forage from falling out. This animal ate up to four meters from the ground. As Robert Bakker has noted, lambeosaurines had narrower beaks than their hadrosaurine cousins, which could imply that Parasaurolophus and its relatives may have been more selective. when eating food.

Growth and development

Parasaurolophus is known from many adult specimens, and a juvenile described in 2013. The juvenile was discovered in the Kaiparowits Formation in 2009. Excavated by the joint Webb Schools and Museum expedition of Paleontology Raymond M. Alf, the juvenile has been identified as being about a year old when it died. Referring to Parasaurolophus sp., the juvenile, under specimen number RAM 14000, is the most complete and youngest Parasaurolophus ever found, and It measures 2.5 meters. This individual fits perfectly into the currently known growth stages of Parasaurolophus, and lived approximately 75 million years ago. Although a complete skull from the age intermediate between RAM 14000 and an adult Parasaurolophus has not yet been found, a partial braincase of approximately the correct size is known. At 25% of the total size of adults, juveniles show that crest growth in Parasaurolophus began earlier than in related genera, such as Corythosaurus. It has been suggested that adults of Parasaurolophus carried such large crests, especially compared to the related Corythosaurus due to this age difference between when their crests began to develop.. Its age also means that Parasaurolophus had a very rapid growth rate, which took place in about a year. The crest of the juvenile is not long and tubular like that of adults, but rather low and hemispherical.

The skull of RAM 14000 is almost complete, with only part of the maxilla missing on the left side. However, the skull was split in half by erosion, possibly while it was resting at the bottom of a river bed. The two sides are slightly displaced, with some bones on the right protruding from the main block, also due to erosion. After reconstruction, the skull seen from the side resembles other juvenile lambeosaurines found, being approximately trapezoidal in shape.

A partial cranial endocranium for RAM 14000 was reconstructed from computed tomography data, the first for a Parasaurolophus of any ontogenetic stage. The endocranium was reconstructed in two sections, one in the part of the braincase articulated with the left half of the skull and the rest in the disarticulated part of the braincase. Their relative position was then approximated based on cranial landmarks and in comparison with other hadrosaurids. Due to weathering, many of the smaller neural canals and holes could not be identified with certainty.

Cranial crest

Many hypotheses have been proposed to explain the functions of the cranial crest of Parasaurolophus, but many have been refuted. It is currently considered that it most likely had several functions simultaneously, such as part of a system of visual individualization of the species and sex, sound amplification for communication and thermoregulation. What is not clear is what was the main driver for the evolution of the crest and internal canals.

Differences between species, sex and age

As in other lambeosaurines, it is believed that the cranial crest of Parasaurolophus changed with age and in the adult they were different between the sexes. James Hopson, one of the first researchers to describe the crests of lambeosaurines in terms of their differences, suggests thatP. cyrtocristatus, with its small crest, is a female of P. tubicen. Thomas Williamson has instead suggested that it is a juvenile form of this. None of these hypotheses has been widely accepted. With only six good skulls and one juvenile, additional material is necessary to clarify this situation. Williamson noted that, in any case, the young Parasaurolophus probably had rounded crests like P. cyrtocristatus that probably grew rapidly as the animal approached sexual maturity. Recent studies of juvenile skulls previously assigned to Lambeosaurus and now considered Parasaurolophus provide evidence of a small tubular crest present in young. This specimen preserves a small ascending mark in the middle of each frontal bone that is similar but less noticeable than those seen in adults. In these, the frontals form a platform that supports the base of the crest. This specimen also indicates that the crest growth in Parasaurolophus and the facial profile of juvenile individuals differed from the Corythosaurus-Hypacrosaurus-< model. i>Lambeosaurus, in part due to the crest of Parasaurolophus lacking the thin comb-shaped bone that makes up the upper portion of the crest of the other three lambeosaurines.

Social function

Taking into account the social and physiological point of view, the functions of the crest have been proposed; they have more to do with visual identification and sound communication. As a large object, the crest has clear value as a visual cue and distinguishes this animal from its contemporaries. The large size of the ocular orbits and the presence of a sclerotic ring in the eyes imply acute vision and diurnal habits, evidence that sight was important for these animals. If, as commonly illustrated, a sail of skin extended from the crest to the neck or back, the effect of standing out from the others would have been even more striking. As has been suggested by the skulls of lambeosaurines, the crest of Parasaurolophus would allow it to identify itself from other similar dinosaurs such as Corythosaurus or Lambeosaurus and recognize the sex and age of another of its species by size and shape. shape.

Function in sound emission

The external appearance of the crest, while quite simple, does not correspond to the complex internal anatomy of the nasal passages, suggesting that they would have some other function. Carl Wiman was the first to propose, since in 1931, that the passages would have served to emit an identifying sound, similar to that produced by a cromorno. Hopson & David B. Weishampel revisited that idea in the 1970s and 1980s. Hopson found that there is anatomical evidence that hadrosaurids had acute hearing. There is at least one example, in the related Corythosaurus, of a thin stapes (reptilian ear bone) in place, which combined with a large space for the eardrum implies a sensitive middle ear. Furthermore, in hadrosaurids the end of the cochlear duct is elongated as in crocodilians, indicating that the auditory portion of the inner ear was well developed. Weishampel suggests that P. walkeriwas capable of producing sound frequencies between 48 to 240 Hz, and P. cyrtocristatus (interpreted as a juvenile-shaped crest) between 75 to 375 Hz. Based on the similarity of the inner ears of hadrosaurids to those of crocodiles, he proposed that adults were sensitive to high frequencies, such as those that would produce the offspring. According to Weishampel, this is consistent with communication between parents and offspring.

A computer model of the well-preserved crest of P. tubicen, which had more complex air passages than P. walkeri, led to the reconstruction of the possible sounds it would produce. The main path resonates at approximately 30 Hz, but the complicated anatomy of the sinuses causes peaks and valleys in the sound . The other main behavioral theory is that the crest was used for intraspecific recognition. This means that the crest could have been used for species recognition, as a warning signal, and for other non-sexual uses. These could have been some of the reasons why crests evolved in Parasaurolophus and other hadrosaurids.

Function in thermoregulation

The large exposed area and vascularization of the ridge has led to the belief that it would also have a function in thermoregulation. P.E. Wheeler was the first to propose this use in 1978 as a way to cool the brain. Teresa Maryańska and Osmólska proposed the thermoregulatory function around the same time, and Sullivan & Williamson took it as an object of study. David Evans' 2006 dissertation on the function of the lambeosaurine crest, at least as an initial factor for the evolution of crest extension.

Rejected hypotheses about crest function

Many of the early suggestions focused on adaptations for an aquatic life form, following the hypothesis that hadrosaurids were amphibians, a common line of thought until the 1960s. Thus, Alfred Sherwood Romer proposed that it served as a snorkel, Martin Wilfarth, which was the support for a mobile proboscis used as a tube for breathing or taking food, Charles M. Sternberg, which would have served as an air trap to prevent water from reaching the lungs, and Ned Colbert, which would have been an air reservoir to prolong his stay underwater.

Other suggestions were more physical in nature. As mentioned above, W. Parks suggested that it was attached to the vertebrae with ligaments or muscles, and helped with the movement and support of the head. Othenio Abel proposed that it was used as a weapon in combat with others of its species, and Andrew Milner, which was used to make its way through foliage, as the cassowary does today. On the other hand, it was also proposed that it would house special organs. Halszka Osmólska suggests that it housed a salt gland, and John Ostrom that it was covered with olfactory-sensitive tissue and the enhanced sense of smell of lambeosaurines, which had no obvious defensive capabilities. An unusual hypothesis was given by creationist Duane Gish., in which the crest would house glands capable of emitting a "chemical fire" to their enemies, similar to that of today's bombardier beetles. Most of these hypotheses have been discredited or rejected. For example, there is no hole at the end of the ridge for a snorkeling feature. There are no muscle insertion scars for a proboscis and it is doubtful that an animal with a beak would need one. As an air trap, it would not have stopped water from entering. The proposed air reservoir would have been insufficient for an animal the size of Parasaurolophus. Other hadrosaurids had large heads without the need for large hollow crests to serve as attachment points for supporting ligaments. None of the proposals explain why the crest has such a shape, why other lambeosaurines have crests that look very different but perform a similar function or how hadrosaurids without crests or with a solid one managed to survive without such abilities, or why some hadrosaurids had solid crests. These considerations particularly affect hypotheses based on increasing the capabilities of systems already present in the animal, such as the salt gland and olfaction hypotheses, and indicate that these were not the primary functions of the crest. Furthermore, work on the lambeosaurine nasal cavity demonstrates that the olfactory nerve and corresponding sensory tissue were largely outside the nasal passages portion of the crest, so the extent of the crest had little to do with the sense of smell.

Paleopathology

Parasaurolophus walkeri is known from a specimen that could contain a pathology. The skeleton shows a V-shaped gap or notch in the vertebrae at the base of the neck. At first thought to be pathological, Parks published a second interpretation of this, as an attached ligament to support head. The crest would be attached to the space through muscles or ligaments, and would be used to support the head while carrying a frill, as is predicted to exist in some hadrosaurids. Another possibility is that during preparation, the specimen was damaged, creating possible pathology. However, the notch is still considered more likely to be pathology, although some illustrations of Parasaurolophus restore the skin flap.

Parks noted another possible pathology, and around the notch. In the fourth, fifth, and sixth vertebrae, directly anterior to the notch, the neural spines were damaged. The fourth had an obvious fracture, and the other two had swelling at the base of the fracture.

The holotype of P. walkeriin the Royal Ontario Museum, Canada, shows various paleopathologies, a dental lesion in the left maxilla, perhaps related to periodontal disease, callus formation associated with fractures in three dorsal ribs, a discoidal overgrowth above of dorsal neural spines six and seven, a cranially oriented vertebral spine on dorsal seven, which fuses distally with that of dorsal six, a V-shaped space between dorsal spines seven and eight and a ventral projection of the pubic process of the ilium that covers and fuses with the lateral side of the iliac process of the pubis. These injuries suggest that the animal suffered one or more traumatic events, the main one causing a series of injuries to the anterior aspect of the thorax. The presence of multiple lesions in a single individual is a rare observation and, when compared to a major database of hadrosaurid paleopathological lesions, has the potential to reveal new information about the biology and behavior of these ornithopods. The precise etiology of the iliac anomaly remains unclear, although it is believed to have been an indirect consequence of the previous trauma. The discoid overgrowth above the two neural spines also appears to be secondary to severe trauma inflicted on the ribs and dorsal spines, and probably represents post-traumatic ossification of the base of the nuchal ligament.

In popular culture

Parasaurolophus rose to fame thanks to the 1993 film Jurassic Park, directed by Steven Spielberg, and has appeared in all the films of the eponymous franchise: in the first movie a herd appears (for a few seconds) along with a group of brachiosaurs. In the second film, The Lost World: Jurassic Park, Parasaurolophus appears more than the other chapters; InGen captures a specimen under the eyes of Ian Malcolm's team. Several specimens of Parasaurolophus appear in two Disney classics: Fantasy (1940) and Dinosaur (2000). This dinosaur was also planned to appear in Ice Age: Dawn of the Dinosaurs (2009) and appears in the film The Good Dinosaur (2015).

It has also been present in various series and games, among them Dino King, which presents a female Parasaurolophus called Paris, with an element of grass and is one of the protagonist dinosaurs. Likewise, we have a Parasaurolophus named Perry who along with his species are presented in Dinotren.

Contenido relacionado

French Academy of Sciences

History of science

Hildegard of Bingen

Grain (unit of mass)

Averroes