Papyrus

Papyrus (from the Latin papyrus, and this from the Greek πάπυρος) is the name given to the writing support made from Cyperus papyrus, a marshy aquatic herb of the Cyperaceae family, very common in the Nile River in Egypt and in some parts of the Mediterranean basin. In addition to writing material, the ancient Egyptians used papyrus in the construction of other artifacts, such as reed boats, mats, ropes, sandals, and baskets.

Etymology

The word papyrus comes from the Greek term πάπυρος papyros, which in Latin is papyrus (the plural is papyri), used by the Egyptians anciently. It is taken from the ancient Egyptian term, which means 'king's flower', since its elaboration was a royal monopoly. It is also the origin of the word paper.

History

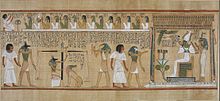

Papyrus was first made in Egypt as early as the fourth millennium BC. The oldest archaeological evidence for papyrus was excavated in 2012 and 2013 at Wadi al-Jarf, an ancient Egyptian port located in the Red Sea coast. These documents, Merer's Journal, date to c. 2560-2550 BCE (late Khufu's reign). Papyrus scrolls describe the last years of construction of the Great Pyramid of Giza. In the first centuries before and after Christ, papyrus scrolls gained a rival as a writing surface. in the form of parchment, which was prepared from animal skins. Sheets of parchment were folded to form notebooks from which book-shaped codices were formed. Early Christian writers soon adopted the codex form, and in the Greco-Roman world, it became common to cut sheets from papyrus scrolls to form codices.

Codices were an improvement over the papyrus scroll, since papyrus was not flexible enough to bend without cracking and a long scroll was required to create large volume texts. Papyrus had the advantage of being relatively cheap and easy to produce, but it was brittle and susceptible to both moisture and excessive dryness. Unless the papyrus was of perfect quality, the writing surface was uneven and the range of media that could be used was also limited.

Papyrus was replaced in Europe by parchment and vellum, cheaper locally produced products of significantly greater durability in humid climates, although Henri Pirenne's connection of its disappearance to the Muslim conquest of Egypt between 639 and 646 is disputed. Its last appearance in the Merovingian chancery is with a document from 692, although it was known in Gaul until the middle of the following century. The latest dates determined for the use of papyrus are 1057 for a papyrus decree (typically conservative, all papal bulls were on papyrus until 1022), under Pope Victor II, and 1087 for an Arabic document. Its use in Egypt continued until it was replaced by the less expensive paper introduced by the Islamic world who originally learned it from the Chinese. By the 12th century, parchment and paper were in use in the Byzantine Empire, but papyrus remained an option.

Papyrus was made in various qualities and prices. Pliny the Elder and Isidore of Seville described six variations of papyrus that were sold in the Roman market of the time. These were graded for quality based on how fine, firm, white, and smooth the writing surface was. Grades ranged from the augustic superfine, which was produced on sheets 13 digits (25 cm) wide, to the less expensive and thicker, which measured six digits (15 cm) wide. Materials deemed unusable for writing or with fewer than six digits were deemed commercial grade and glued edge-to-edge to be used for wrapping only.

Until the middle of the 19th century only a few isolated documents written on papyrus were known, and museums displayed them simply as curiosities They contained no literary works. The first modern discovery of papyrus scrolls was made at Herculaneum in 1752. Until then, the only known papyri had been some surviving mediaeval papyri. Scholarly research began with the Dutch historian Caspar Jacob Christiaan Reuvens (1793–1835). He wrote about the contents of the Leyden Papyrus, published in 1830. The first publication has been credited to the British scholar Charles Wycliffe Goodwin (1817–1878), who published for the Cambridge Society of Antiquities one of the Greek Magical Papyri V, translated into English with commentary in 1853.

The plant

Like the tiger nut, it belongs to the Cyperaceae family. Some parts of the plant are edible and boats can be made from the stems. Nowadays it is also an ornamental plant (umbrella)

It is a robust aquatic plant that can reach 5 m in height. It has triangular stems that come out of a woody rhizome. Each stem terminates in a dense clump of stems 10 to 30 long that are leaden in appearance when the plant is young. Blooms in late summer. The flowers are green-brown in clusters that appear at the end of the small stems and give rise to nutlet fruits that spread through the water. The leaves only appear on the rhizomes.

The papyrus plant is found in tropical and subtropical waterways. In the Nile River it is currently in danger of extinction and in the past it had been cultivated. It also appears in the Niger and Euphrates rivers as well as in the Okavango Delta. It is sensitive to frost.

Papyrus as a writing medium

It was extensively used for the manufacture of various everyday objects, and its main use was the preparation of the ancient manuscript support called papyrus, a precedent for modern paper. The oldest fragment of papyrus was discovered in the tomb of Hemaka, chaty of Pharaoh Den, in the Saqqara necropolis, although possible hieroglyphic signs written on it have not survived.

Its elaboration was a royal monopoly and it was highly appreciated for its great utility among the peoples of the eastern Mediterranean basin. It was exported for centuries in highly valued rolls, as described in the account of Unamón's voyage.

The use of papyrus did not become universal until the time of Alexander the Great (4th century BC). Its use declined with the decline of the ancient Egyptian culture, and it was replaced as a writing medium by parchment. It declined over the course of the V century and disappeared entirely in the West in the XI because the Mediterranean trade routes were cut off by the advancing Arabs. Most of the great libraries in Europe have papyrus manuscripts.

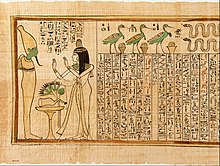

Elaboration of papyrus paper

First, the stem of the papyrus plant was soaked for one to two weeks; then it was cut into thin strips called phyliae and they were pressed with a roller, to eliminate part of the sap and other liquid substances; then the sheets were arranged horizontally and vertically, and they were pressed again, so that the sap acted as an adhesive; it ended up being gently rubbed with a shell or a piece of ivory, for several days, being ready for use.

The unit of measure for papyrus was the plagula (leaf). They used to make papyrus rolls of about twenty plagulas that were glued together, with a total average size of five meters. The largest papyrus found is the Harris I Papyrus, which measures more than 41 meters.

- Texts

- The inscriptions were made on the face of the papyrus that had the strips arranged horizontally: the opposite. On the other side (the reverse) was rarely written (in this case they are called opistographers) although, because it was very expensive, if what was written lost interest, it was deleted and used again (see palimpsest). For this reason, for the minor writings, the ostracs were used instead.

- Use

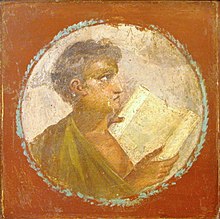

- The volume was stored in a parchment case dyed sometimes red with the orange juice (Vaccinium). A piece of parchment (titulus, index) he joined the roll and was sometimes written with red ink, the title of the work. The reader held the volume with his right hand, and was unfolding it with the left; it served him to roll the part of the book already read; hence the expressions evolvere, explicare, ad umbilicum pervenireto mean that it had come to the end of the text.

Symbolism

It is the sacred papyrus, used to make the boats of the gods of Ancient Egypt. The plant also had a religious function that emerged in ancient times: born in the sacred Nile, it was represented in temples and was carried in processions, where it symbolized the rebirth and regeneration of the World. A specific plant from the Nile Delta, this was the emblem of Lower Egypt and represented the goddess Wadjet (wady: papyrus hieroglyph, also meaning malachite green, and "prosperity"). The papyrus plant was represented since predynastic times as a symbol of Lower Egypt; figure in the votive mace of Horus Scorpion.

Other uses of papyrus

The writing support was not the only product made in Ancient Egypt from this plant, very common in ancient times, basketry objects, sandals, breeches, ropes, and even boats could also be made. Its root was consumed and sometimes the interior of the stem. It was also said to have healing qualities. At present the plant, almost disappeared in Egypt, is used to make tourist objects.

Classification of papyri

According to Pliny the Elder, they were classified by quality into eight classes:

- Courageous: those of lower quality, used as wrapping paper.

- Taenetics: those of poor quality.

- Satellites: those of low quality, made with surplus materials.

- Amphitatrics: medium quality.

- Fanianos: those of good quality.

- Livios: those of very good quality.

- Augusticos: high quality.

- Hyderatics or regimens: the highest quality, only used for sacred texts.

Some of these names come from various reasons:

- From where it was manufactured, like sathic paperfrom the city of Sais.

- From the factory name as amphitheatricThe host of Alexandria.

- The factory owner, like Janinian Jannio Palemon.

- From the character to whom he was dedicated, as Augusto, Livian, Claudiofor being the emperors and emperatrics of this name.

- From his destiny, as hierarchyfor being destined for sacred uses.

- From the main group that used it, like emportic or empiricalwhich was more rude and served to wrap goods.

- From other circumstances, such as the call charta dentadaFor being brunt with animal teeth, mainly of the wild boar.

Due to the large number of papyri found, various and disparate classification schemes are used to identify them, as follows:

- By the person or foundation that possessed the manuscript: Papiro Westcar, Bodmer sighs 14 and 15 known as P75

- By the place of origin: Oxyrhynchus Papyri

- By the place where it is preserved: Canon of Turin, Papiro Rylands P52

The papyri are also assigned a number, to facilitate their identification in the classification work.

Papyruses and the Bible

- Plant references and their uses

Moses describes in the book of Exodus 2:3 how his mother protected him and led to his chance meeting with Pharaoh's daughter.

When he could no longer hide it, then he took for him an ark of Daddy and gave him a hand of bitumen and fish, and put the child in it, and laid it among the reeds, by the margin of the river Nile.

On the other hand, the book of Job makes reference to the papyrus plant when Bildad —one of Job's three friends— asks him: “Will the papyrus grow and become tall without a swampy place? (Job 8:11)

In Isaiah 18:2 it is said that larger boats were made of papyrus to travel longer distances.

It is the one that dispatches through the sea, and through papyrus vessels on the surface of the waters, [saying:] “Go, quick messengers, to a nation of high size and sharp, to a people who everywhere is inspiring of fear, to a nation of resistance to tension and trampling, whose land has rolled the rivers.”

- Use as writing material

The work Insight into the Scriptures says that [at the time the Bible was written] the sheets could be glued together at the ends to form a scroll, which used to consist of about twenty sheets. They could also be folded into sheets to form the book-like codex popular with early Christians. A scroll measured an average of 4 to 6 m long, although a 40.5 m specimen is preserved. Originally, the Greek word bi‧blos designated the soft pith of the papyrus plant, but was later used to refer to the book itself. (Mt 1:1; Mr 12:26) The diminutive bi‧blí‧on has the plural of the word bi‧blí‧a, literally meaning “little books,” from which the word “Bible” is derived. (2Ti 4:13, Int.) Byblos was a Phoenician city that owed its name to the fact that it was an important center of the papyrus industry.

Papyrus scrolls were in common use until the early II century, when the papyrus codex began to replace them. Later, in the IV century, the popularity of papyrus began to wane and it was replaced by a much more durable writing material.: the vellum.

Papyrus had one major drawback as a writing material: it was not very durable. It deteriorated in a humid environment and became very brittle when stored in an environment that was too dry. Until the 18th century it was assumed that all ancient biblical manuscripts written on papyrus had disappeared. However, at the end of the XIX century, a good number of biblical papyri were discovered both in Egypt and around the Dead Sea, places with a moderately dry climate, very necessary for the conservation of the papyri. Some of the Biblical papyri found at these sites date back to the II or 2nd century. caps;text-transform:lowercase">I a. c.

Many of these papyrus manuscripts are referred to as "papyruses", such as the Nash Papyrus of the 1st century or II a. c.; the Rylands III Papyrus, 458 (II century BC), and the Chester Beatty Papyrus no. 1 (III century).

Contenido relacionado

Fadrique de Toledo Osorio (1580-1634)

Firebird

The night of the generals