Pamir Mountain Range

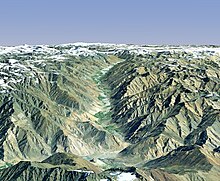

The Pamir, Pamir knot or Pamires —or even less accurately the Pamir mountain range—, is a high mountain massif in the Central Asia centered on the Upper Badakhshan region of eastern Tajikistan, which extends across Afghanistan, the People's Republic of China, Kyrgyzstan and Pakistan. Orographic knot located at the junction of several systems - the Tian Mountains, to the north, the Kunlun mountain range, to the east, the Karakoram, to the south, and the Hindu Kush, to the southwest -, it has three main peaks of more than 7000 m—such as Ismail Samani Peak, generally considered its highest point at 7495 m—, which makes it the fifth highest mountain system in the world, and one of the only six that exceed seven thousand meters. Along with Tibet, it was known in the 19th century as the “Roof of the World.” /i>), in a rough translation of the Persian term. It is also known by its Chinese name, Congling.

Pamir is also applied to a certain type of glacial valley that is more fertile than the mountains and plateaus that surround it. The latter are generally subject to extreme climatic conditions, with little rainfall and significant temperature differences, particularly in the eastern desert half of the massif. However, the Pamirs are one of the regions with the most glaciers outside the polar regions, including the 77 km long Fedchenko Glacier. This allows it to be crossed by a large number of rivers that belong to the Amu Daria basins, in the west, and the Tarim, in the east, and have hundreds of lakes. Although the poverty of the flora characterizes the unique ecoregion of tundra and high-altitude desert of the Pamirs, the fauna is very diverse, with the Marco Polo argali standing out, an endemic species threatened with extinction.

The massif has been frequented by man for several millennia of years. Lapis lazuli found in Egyptian tombs is considered to have come from the Pamir region. Around 138 BC. C. Zhang Qian ascended the Fergana Valley, northwest of the Pamirs. Claudius Ptolemy already vaguely described the trade route in this area. Around the year 600, Buddhist pilgrims traveled on both sides of the Pamirs to reach India. from China. In the year 747, an army from the Tang dynasty was on the Wakhan River. Secondary routes of the Silk Road have been found in the massif since ancient times. However, only the Tajiks since the II century and the Kyrgyz, from the XVI, they settled there. Marco Polo, in the 13th century, was the first European to mention his crossing of the Pamirs. Few followed in his footsteps until the middle of the 19th century — Bento de Goes, who traveled from Kabul to Yarkand, is remembered in 1602 and that he left a report on the Pamir massif—when it was explored; In 1838 Lieutenant John Wood reached the headwaters of the Pamir River. From about 1868 to 1880, a number of Hindus from the British Secret Service explored the Panj area. And the region was the heart of a geopolitical conflict, The Great Game, between the Russian Empire, in the north, and British India, in the south. The massif fell into Western oblivion in the 20th century. In the 21st century, it is populated by different populations that have adapted to the mountains: the Tajiks, to the west and south, and the Kyrgyz, to the north and east. The latter lead a semi-nomadic life, taking their animals to graze in the few fertile pamirs. They have perpetuated a culture rich in many particular traditions.

The Pamirs remain one of the most isolated regions in the world. The infrastructure is very underdeveloped and the population continues to depend on external aid. Tourism, focused mainly on mountaineering, hiking and ecotourism, is developing, despite the existence of many protected areas, including the Pamir national park, which is the largest in Central Asia.

Covered by snow most of the year, and beaten by abundant hail, the Pamirs enjoy an alpine climate with long, very cold winters and short, cool summers. The annual precipitation, with an average of 130 mm, only manages to maintain grasslands and very few trees.

Toponymy

The Buddhist monk Xuanzang was the first to evoke in his writings, around 640, the Po-mi-lo or Pho-mi-lo, the plateau of Pamir. This spelling is very close to Kyrgyz Pamil, the word for a mountainous area. The term was taken up in the form Pomi in the mid of the 8th century under the Tang dynasty. Xuanzang placed it at the center of the Congling or Tsoung Ling (葱嶺), literally the "Onion Mountains", which extended over a perimeter larger than the Pamirs in its usual geographical sense.

According to Eugène Burnouf, Pamer, Pamere or Pamier —the spellings used by Marco Polo in the century XIII, and then by Mountstuart Elphinstone and Alexander Burnes in the century XIX—, would derive by syncope from the Sanskrit Oupa-Mérou, that is, the "neighboring country of Meru", while according to the spelling that appeared in 1543, under the pen of the prince of Kashgar Mirza Haidar —and later used by John Wood and Alexander von Humboldt—, Pamir would derive from Oupa-Mira, the “country around the lake”, which according to him, would allude to the lake Zorkul.

The British orientalist Gottlieb Wilhelm Leitner rejected these theories, recalling that the people who frequented the pastures of these plateaus or high valleys every summer spoke Turkic languages, especially Kyrgyz and Ili Turki, and that they were designated interchangeably under the name pamires. Thus, pâ could mean "mountain" and mira would be a "vast region" or a "plateau"; According to a concurrent explanation, pan or pai would designate the "foot" or the "base" and mir the "mountain", whether the "pie de monte of the mountain" or the "base of the mountain." These pamirs would be seven or eight valleys, although an alternative hypothesis is that the word did not designate a specific type of valley but rather a very particular valley, that of the Lake Zorkul. By extension, the pamirs would simultaneously form a vast pamir, which would be the Pamir region. Another linguistic explanation, although implausible, wants that Pa-i-michr means "basement of the sun" in Uzbek and would have been interpreted as "foot of Mithra", the equivalent of the sun god in Indo-Iranian mythology.

The location of the massif has earned it locally, according to Wood, the adjective Bam-i-dunya, the "roof of the world" in Wakhi or Kyrgyz. It would derive from pay-i-mehr and then Bamyar in Persian. Be that as it may, the expression became common in the Victorian era. In 1876, Thomas Edward Gordon wrote:

Now we were about to cross the famous Bam-i-dunya, the "them of the world" name under which the elevated region where clues until then relatively unknown appeared on our maps. [...] Wood, in 1838, was the first modern European traveler to visit the Grand Pamir.Nous étions désormais sur le point de traverser le fameux Bam-i-dunya, le « toit du monde » en vertu duquel le nom de la région élevée où des pistes jusque-là relativement inconnues apparaissaient sur nos cartes. [...] Wood, in 1838, était le premier voyageur européen des temps modernes à visiter le Grand Pamir.The roof of the world: being a narrative of a journey over the high plateau of Tibet to the Russian frontier and the Oxus sources on Pamir (1876)

The expression was taken up in 1890 by Guillaume Capus; in 1911, in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica; in 1929, in the Brockhaus Enzyklopädie; or, again in 1942, in the Encyclopédie Columbia.

The Pamir Mountains are written: Кӯҳҳои Помир (Kūhhoi Pomir), in Tajik; Памир тоолору (Pamir tooloru), in Kyrgyz; رشته کوههای پامیر (rechté kouh-hâyé pâmir), in Persian; د پامير غرونه (pamir ghroona), in Pachto; پامىر ئېگىزلىكى, in Uyghur; پامیر کوهستان (pāmīr kūhistān), in Urdu; पामीर पर्वतमाला (pāmīra parvatamālā), in Hindi; and 帕米尔高原 (Pàmǐ'ěr Gāoyuán) in Chinese.

For Robert Middleton, "pamir" is also a geomorphological term, which would designate a flat plateau or a valley surrounded by mountains. It would be formed when a glacier or icy surface melted, leaving a rocky plain. The pamir would last until erosion formed the soil and reduced it to a normal valley. This type of terrain is found mainly in the east and south of the Upper Badakhshan province, unlike the valleys and ravines of the west. The Pamirs They were used for summer grazing. (Note that the sources cited in Thomas and Middleton's work are all from the beginning of the century XX, so they can be considered scientifically surpassed today.) There are seven or eight, depending on the source: the Great Pamir, which is in Lake Zorkul: the Little Pamir, which is located towards the northeast Aktash; the Taghdumbash Pamir, which is between Tashkurgan and the Wakhan corridor, along the Karakoram highway; the Alichur Pamir, located around Yashil Kul, on the Gunt River; the Sarez Pamir, which is around the city of Murghob (in Tajikistan); and the Khargush Pamir, which is south of Lake Kara-Kul. There are several others. The Pamir River is in the south.

Geography

Situation

Located in Central Asia, the Pamir Mountains form an orographic knot formed by the convergence of the Tian Mountains to the north, the Kunlun mountain range to the east, the Karakoram Mountains to the south, and the Hindu Kush to the east. southwest. They are centered on the autonomous province of Upper Badakhshan, which they occupy entirely. They are located in the east of Tajikistan and are divided into seven raions: Darvaz, Vanch, Rushan, Shugnan, Roshtkala, Ishkashim and Murghob, which are adds the city of Jorog, capital of the autonomous province. The mountains also extend over a part of the Region under republican subordination, as well as in the Osh oblast, in southern Kyrgyzstan; also through the province of Badakhshan, in northeastern Afghanistan; and in the Xinjiang Uyghur Autonomous Region, in the People's Republic of China. Its southern limit is marked by the Wakhan corridor where the Wakhan-Daria flows, extended by the Piandj River, while its northern limit is formed by the vast depression of the Alay Valley that houses the Kyzyl-Sou, in the upper course of the Vajsh River. Its eastern border, with the Kunlun, is more controversial; Some make it pass through a wide fault along which the Karakoram Highway runs, others push it further east, with a margin of acceptance of 150−200 km. Its western extensions are relatively vague, since the relief gradually decreases. Thus, the Great Soviet Encyclopedia notes:

The question of the natural borders of the Pamir is questionable. Usually, it is considered that the Pamir includes the territory of the Trans-Alai mountain range in the north, the Sarikol mountain range in the east, the Zorkul lake, the Pamir river and the upper Piandj river, in the south, the middle section of the Piandj valley in the west; towards the northwest, the Pamir includes the eastern parts of the Pedro I and Darvaz mountain ranges. [...] Some researchers have restricted this interpretation, including only the eastern part of that territory, while many, on the contrary, consider the Pamir more broadly to include the mountains adjacent to the east and several others nearby.La question des frontières naturelles du Pamir est discussable. Habituellement, le Pamir est considéré comme couvrant le territoire du string Trans-Alaï au nord, au chain Sarikol à l'est, au lac Zorkul, la rivière Pamir et le cours supérieur du Piandj au sud, à la section médiane de la vallée du Piandj à l'ourd Certains chercheurs ont restreint cette interprétation, n'y incluant que la partie orientale de ce territoire, alors que beaucoup, inversement, considèrent le Pamir plus largement pour inclure les montagnes contiguës à l'est et diverses autres à proximité.

Relief

Geomorphology

The Pamir mountain range extends for about 500 km in the E-W direction and about 300 km in the N-S. Despite having limits that may vary depending on the authors, it is possible to distinguish two large groups in the chain: a western part, composed of the Badakhshan region, with sharp mountains and deep, narrow valleys, crossed by torrents and dotted with small green villages perforated in the cones of ejecta and alluvial terraces; and an eastern part, which presents high isolated and desert plateaus between 3500−4500 m in altitude, made of loose proluvial and morrheic deposits, and crowned by relatively little elevated. The limit between the two groups has traditionally been considered the Zulumart ridge and then the passes of Pereval Pshart and Pereval Kara-Bulak.

In the center of the massif is the chain of the Academy of Sciences, which extends more than 175 km and culminates at 7495 m altitude on Ismail Samani Peak—previously called Stalin Peak (from 1932 to 1962), and then Communism Peak (from 1962 to 1998)—; It also has Korzhenevskaya Peak at 7105 m, often considered the third highest peak in the Pamirs. To the northeast is the Trans-Alaï mountain range, which runs from east to west, parallel to the Alay Valley and the facing Alaï Mountains. It rises to 7134 m altitude on Lenin Peak, formerly Kaufmann Peak from its discovery in 1871 to 1928, officially named since July 2006, Abu Ali ibn Sina Peak in Tajikistan and, sometimes, improperly, Atchik Tash Peak in Kyrgyzstan, named after a plateau and its base camp located at 3600 m altitude. The western slope of the Academy of Sciences range descends steeply and extends with the western foothills, including, from north to south, the Peter I ranges (culminating in Moscow Peak, a 6785 m), Darvaz (on Arnavad peak, at 5992 m), Vanch and Yazgoulem (on Independence, peak of the Revolution until 2006, at 6974 m). To the south, the ranges Rushan (Patkhor peak, 6083 m), Shugnan (Skalisty peak, 5707 m), Roshtkala (5321 m) and Shakhdara or Ishkashim (Karl Marx Peak, 6726 m) are separated by deep gorges, generally oriented east-west and frequently filled by landslides caused by earthquakes. They extend eastwards by high plateaus from which the Muskol ranges emerge (Soviet Officer's Peak, 6233 m), Murghab or Northern Alitshur (5617 m), Southern Alitshur (peak Kysyldangi, 5704 m) and Wakhan or Selsela-Koh-i-Wākhān (6421 m), among which there are several lakes, including Kara-Kul at 3900 m altitude. Finally, the Sarikol chain, nicknamed the « Chinese Pamir» although bordering with Tajikistan, closes from north to south the Pamir plateaus in the eastern confines of the massif, which culminates in the Lyavirdyr peak at 6351 m altitude, opposite the peaks Kongur and Muztagh Ata. The latter are part of a group sometimes known as the Kashgar (or Kandar) range, once included in the Pamirs, but more generally considered a northern extension of the Kunlun mountain range, since a wide arm separates it from the Pamir proper.

Traditionally they are considered as pamirs - generic name for isolated and fertile glacial valleys only crossed by Kyrgyz nomads, which are closed by moraines and irrigated naturally - the following seven u eight valleys:

- The Pamir Taghdumbash, nicknamed the "Supreme Mountain Cabeza" or "Pamir of the Mount", which lies between the Sarikol mountain range, in the north, and the Kilik Pass (4827 m) in the south, in the southwest of the Tajik autonomous xian of Taxkorgan, in China. It is closed to the west by the Wakhjir Pass (4923 m) that separates it from the upstream part of the Wakhan-Daria valley. It descends eastward before turning north to Tashkurgan, to some 3000 m At altitude, at a distance of a hundred kilometers. He's the only one. Pamir that belongs to the Tarim basin. It is populated by Kyrgyz, Sarikolis and Wakhis.

- The Pamir Wakhan, located at the eastern end of the Wakhan corridor in Afghanistan, north of the Karakoram, upstream of the town of Baza`i Gonbad. It descends about thirty kilometres west-west. It's the narrowest of all Pamirs. It offers rich pastures.

- The Pamir Khord or Pamir Kitshik, better known as Small Pamir, is located between the Selsela-Koh-i-Wākhān, in the north, and the Karakoram, in the south, between Lake Chaqmaqtin and the village of Sarhad, in the central part of the Wakhan corridor. It is in contact in the northeast with the Oksu valley. It extends south-south over a hundred kilometers.

- The Pamir Kalan or Pamir Tshong, best known as Grand Pamir, which is, as its name indicates, the longest and widest of all Pamirs. It is a booming valley that extends about 130 kilometres from Lake Zorkul to the south-south, between the southern Alitshur chains, in the south, and Selsela-Koh-i-Wākhān, in the north, and which houses the course of the Pamir River.

- The Pamir Alitshur, a little further north, extending between the northern and southern chains of the same name. It contains the Yashilkul lakes, Bulun-Kul and Sasyk-Kul and then extends west through the Shugnan.

- The Pamir Sarez (the "pamir of the yellow track"), further north, which is embedded between the Alitshur and Muskol chains, around Lake Sarez. Although it appears on several maps and has seen its existence reported by the explorers, Ney Elias has questioned its existence arguing that it has none of the usual features of a Pamir due to its embedded relief. Francis Younghusband explains that a small fertile valley of about fifteen kilometres in length is more east, around the small town of Murghob, and has been mislined on the maps.

- The Pamir Rangkul (the "Pamir of the Colored Lake"), about forty kilometers long, which is located around the lake of the same name, while the Pamir Khargosh (or Kargushîthe “bird of the rabbit” has thirty kilometres south and east of Lake Kara-Kul; however, its existence is controversial.

Some more valleys have been able to claim the name pamir but due to geomorphological differences and poorly defined local uses, they have been rejected.

Subdivisions and main summits

There follows a summary of the main peaks in order of altitude that make up the Pamirs. The peaks in gray are part of the Kashgar mountain range considered a transition zone with the Pamirs, and even an integral part of the Kunlun mountain range.

Hydrography

The vast majority of the rivers that drain the Pamirs belong to the Amu Darya basin. The most important of these rivers is the Piandj, which is born from the union of the Pamir and Wakhan-Daria rivers and which geographically marks the southern and southwestern limit of the massif, and politically it is the border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. Its main tributary, on the right bank, is the Gunt, which it receives at the level of the city of Jorog, and which is joined by the Shakhdara at the entrance to that agglomeration; follows the Bartang River - called Oksu in its upstream part and Murghab (which means "the water near where birds nest") in its middle part - which arises a few hundred meters from the sources of the Piandj and which, without However, it literally crosses the Pamir from east to west for several hundred kilometers before crossing it; then come the Yazgoulem and the Vanch. Marking the northern border of the Pamirs under the names of Kyzyl-Sou and then Surkhob, the Vajsh River also flows on the right bank into the Piandj, to the west of the massif, on the southwestern borders of Tajikistan, to form the Amu Darya. The Muksu and Obihingou are tributaries on the left bank of the Surkhob that drain the Peter I and Darvaz ranges. A few rivers feed the endorheic Lake Kara-Kul, such as the Karadzhilga and the Muskol. The west of the Sarikol chain belongs to the Tarim basin. There are 173 rivers that flow through the massif, to which must be added more than 200 mineral springs, a third of them hot springs.

The Pamirs would house between 846 lakes (with 1,343 km²) and 1,449 lakes., depending on the sources. In addition to Lake Kara-Kul, which is located on 38,000 hectares in a 25-million-year-old impact crater, in the northeastern Pamirs, and The waters of which are the most basic with a pH between 7.3 and 8.0, include the twin lakes Rangkul and Shorkul on the western slope of the Sarikol mountain range and Lake Zorkul, formed by a moraine, between the southern Alitshur and Wakhan mountain ranges. Turumtaikul Lake is the highest at 4260 m altitude. In the center of the massif, the Yashilkul lakes (the "green lake") and Sarez were created by landslides. The second, a consequence of the 1911 earthquake, is formed naturally by the Usoi dam, the highest in the world. The reservoir is 60 km long and up to 500 m deep. It continues to rise at a rate of twenty centimeters per year, raising fears of the dam breaking and the possible destruction of 32 villages located immediately downstream in the Bartang Valley, to which five million people would be affected in the future. Amu Darya basin. Some lakes freeze from November to May and can be covered with a meter of ice in the middle of winter.

The Pamirs are crossed by 3000 glaciers that cover 8400 km², according to data from the 1970s, or 13,000 glaciers covering 12,000 km² according to more data recent 1990s, but covering broader limits of the massif. They help supply water to 60 million people in Tajikistan, Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Turkmenistan and Xinjiang. Among these, in the chain of the Academy of Sciences, is the Fedchenko glacier, 77 km long, the longest in the former USSR and the longest outside the polar region. At the beginning of In the 1960s, it contained 200 hm³ of ice transformed at altitude thanks to large accumulations of snow. In the Peter I, Darvaz, Vanch and Yazgoulem ranges there are the Grumm-Grzhimailo (36 km), Garmo (27 km), Surgan (24 km), the Institute of Geography glacier (21 km) and Fortambek (20 km). The longest glacier in the Trans-Alaï mountain range is the Great Saukdara glacier, with 25 km, while the Lenin glacier advances at a speed of one hundred meters per day and sometimes advances several kilometers in the valleys. Those Accelerations were observed and explained on the Medvezhy (literally "Bear Glacier") and Bivatchny (lit. "Bivouac Glacier") glaciers not as a consequence of the increase in their volume but as that of an unusual melting that makes the ice already not have the same strength. The Rushan and northern Alitshur ranges also have significant glaciers. However, the area occupied by the glaciers is much smaller than in the last ice age, when they formed a common ice cap with the Hindu Kush and the Tibetan Plateau. Due to climate change, retreat has generally accelerated in the last fifty years, only 3 to 5% in the center and east of the massif but 15% in the west. The Fedchenko Glacier retreated more than 1000 m between 1920 and 2000, including 750 m since 1958, and lost 2 km² of surface area between that same date and 2009. The river's flow has increased by 2% in the last ten to twenty years due to to the melting of glaciers and increased precipitation.

Geology

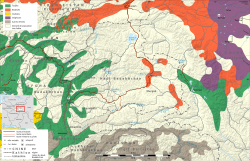

In the Carboniferous, Pangea continued its formation and the Paleo-Tethys ocean closed. Continental collisions occurred, which culminated in the Hercynian orogeny that gave rise to the birth of the Kunlun mountain range system, including the northern part of the Pamir, locally forming a subduction zone. At the same time, the Cimmerian plate was collapsing. It separated Gondwana to the south and allowed the opening of the Neotethys rift during the Permian. The Cimmerian microcontinents continued to move northward and submerged beneath Laurasia. The Paleothetis completely disappeared in the Triassic and accretion at the level of the central and southern parts of the Pamirs ended in the Jurassic. In the Cretaceous, the Indian plate separated from the African plate and migrated northward, while that the Tethys was in turn closed at the level of a new subduction zone, during the Alpine orogeny that also gave birth to the Karakoram. When during the Eocene the Indian subcontinent came into contact with the Eurasian plate, giving rise to the Himalayas, new compressive forces were exerted northwards in the central and southern parts of the Pamirs. These deformations and associated uplift continue.

Due to this geological history, the Pamir is crossed by an important network of faults arranged in circular arcs facing north that delimit different petrological domains. The northern margin of the massif, corresponding to the northern slope of The Trans-Alaï chain is formed by conglomerates, sandstones, clayey schists, limestones and volcanic rocks dating from the end of the Permian to the Cenozoic, which were intensely deformed and uplifted since the middle of the Oligocene. The north of the massif corresponds to the complex anticline that It extends from the southern slope of the Trans-Alaï chain to the important Vanch-Akbaital fault in the south. It is essentially linked to the Hercynian orogeny of the Permian, even though it has been affected by the geological events of the Mesozoic-Cenozoic. Its composition ranges from metamorphic schites from the end of the Precambrian to marbles, sandstones, clay and chalk, and also volcanic rocks from the Paleozoic and granitoid intrusions from the Triassic to the Dogger (Middle Jurassic). A fine transition zone composed of an ophiolite belt is testimony to the obduction of a portion of the oceanic lithosphere at the level of the Vanch-Akbaital fault. To the south, the central part of the Pamirs is covered by a vast nappe formed by Paleozoic sediments and of the Mesozoic deposited on the continental shelf of ancient Tethys, with traces of volcanic rocks from the Miocene. These rocks are strongly deformed by the Alpine orogeny of the Cenozoic. Some windows show slightly metamorphosed schists from the end of the Precambrian and alternations of sedimentary strata, mainly marine, but also bauxites of volcanic origin, from the middle of the Paleozoic to the Upper Cretaceous.. These native rocks have experienced Paleogene and Neogene granitoid intrusions that may have favored local metamorphism. The Rushan Range and Pereval Pshart Pass region consists of Upper Paleozoic terrigenous strata, tilted and dislocated towards the north. They contain diabases and spilites, as well as granitoid intrusions dating from the Jurassic to the Eocene, linked to the Alpine orogeny. It is geologically close to the southeast of the massif, a vast complex syncline, also composed of thick terrigenous marine deposits and granitoid inclusions, to which flyschs from the Triassic and Jurassic are added, as well as sandstones, conglomerates and tuffs from the Cretaceous to Miocene. Finally, the southwest of the massif, isolated by the Hunt-Alitshur fault, is formed by Precambrian schites, gneiss and marbles that were little affected by the successive orogenic phases, with the exception, again, of the intrusions of granitoids from the Cretaceous and Oligocene to Neogene.

The emission of magma on the surface and metamorphism have favored the appearance of crystals and rare metals, mercury, boron, fluorite, calcite, lazurite, spinel and gold. Discovered in 1876 in gemiferous form on Vesuvius by Alfred Des Cloizeaux Clinohumite was discovered in exploitable deposits in 1983, being the only known deposit until the discovery in 2000 of a second deposit in the Dolgano-Nenetsian district of Taimyr, in Siberia and then in 2005 of a third in the Mahenge Mountains in Tanzania.

The formation of pamirs, in the western part of the massif, began in the Miocene under a continental regime and due to the effect of fluvial erosion, starting from the margin and then extending towards the east. As a result, these valleys are strongly indented in the west, are shallower in the central Pamir, and are virtually absent in the eastern part. The Pamir has risen at an average rate of 2.5−3 mm per year for the last few million years. This dynamic continues with measurements reaching 15 mm per year in the Peter I chain. It is sometimes described as the most seismic area in the world, in particular with two earthquakes of magnitude greater than 7 recorded in the first half of the century XX, in Sarez in 1911 and in Khait in 1949, earthquakes each time accompanied by landslides.

Climate

The western part of the Pamirs is subject to a continental climate, with mild, dry summers and long, cold winters. Its eastern part is arid, with a humidity rate sometimes less than 10%, often glacial, subject to intense sunlight and violent winds. Located in the subtropical zone, it is subject to air masses in summer. tropical regions while, starting in October, a depression develops in the west of the massif, which lasts until April, and causes precipitation in the western foothills and retains cold air masses in the east.

Throughout the massif, average annual temperatures vary between 0 and −8 °C and between 2 and 10 °C during the summer period. In the east, in particular, the average temperature in January is −17.8 °C at 3600 m altitude and frequently drops to −50 °C in winter. It has already reached −63 °C in Lake Bulun-Kul, about 4000 m altitude, a national record in Tajikistan. As a result, in the Murghab and Oksu valleys or even in the depression of Lake Kara-Kul, permafrost is present that can reach 80−100 cm. In summer, the amplitude is sometimes greater than 25 °C with frost on the night and rarely more than 20°C during the day. The average temperature in July is 13.9 °C at 3640 m altitude and from just 8.2 °C in Lake Kara-Kul to 3960 m. 24-hour amplitude records reach 60 °C. In the west, at 2160 m altitude, the average temperature in January is −7.4 °C compared to 22.5 °C in July. Temperatures are above 5 °C for 223 days in Jorog and it is only 140 days in Murghob.

The west of the massif generally receives 90 to 260 mm of precipitation per year, with a peak in March and April and a minimum in summer, while They are between 60 and 120 mm in the east, with a slight maximum influenced by the monsoon in May and June and a depression in August. Thus, between July and September, Lake Kara-Kul receives an average 4.8 mm of precipitation. On the periphery of the massif, the town of Garm, in the course middle of the Vajsh River, at 1800 m altitude north of the Peter I range, receives 700 mm annually, while around 3000 m altitude, precipitation can locally reach 1000 mm in the western Pamirs. They translate into significant amounts of snow on the peaks, which is why the permanent weather station on the Fedchenko Glacier, at 4169 m altitude, frequently records cumulative thicknesses of twenty-five meters. For this reason, and thanks to the many days of fog or low clouds that limit the sublimation of the snow, the eternal snow floor, located for example at 4800 m altitude in the western foothills and 5500 m in the chain of the Academy of Sciences, it is the highest in the world. Vladimir Ratzek reports seeing an avalanche evaporate before it even hits the ground, and despite receiving significant snowfall, the ground becomes dry again in just two hours after the sun's reappearance, by sublimation.

Fauna and flora

The massif, in the heart of Central Asia, is part of the Palearctic ecozone. The Pamir high-altitude tundra and desert ecoregion defines its ecosystem in the biome of mountain meadows and shrublands that characterizes it. Despite the extreme climatic conditions, the massif is home to a diversified fauna while the flora is poorer..

Plant and animal life

The variety of topography and climate gives Tajikistan an extremely varied plant life, with more than 5,000 types of flowers alone. Grasses, shrubs and bushes generally predominate. The animal life of the country is abundant and diverse and includes species such as the large gray lizard, gerbil and squirrel in the deserts and deer, tigers, jackals and wild cats in the forested areas or reed thickets. The brown bear lives in the lower levels of the mountain, and the goats and golden eagles in the higher levels.[7]

Flora

Annual rainfall supports grasslands but few trees. A forest belt is present almost exclusively in the western foothills of the massif, on the western slope of the mountains, between the 1500 −2800 m altitude. It consists of maples, walnuts, plum and crab apple trees, junipers, rhododendrons and birches; no pine or spruce is present naturally. Along the banks, willow, buckthorn, poplar, birch and hawthorn form thickets (locally called tugai). The subalpine floor occurs between 2700−3500 m; although it has some scattered shrubs - often in dwarf form, in particular junipers of the species Juniperus pseudosabina that resist well the altitude—, alpine grasses dominate. They are found Saponaria griffithiana, Arabis kokanika, Christolea pamirica, Didymophysa fedtschenkoana, Rosularia radicosa, Astragalus ophiocarpus, Braya scharnhorstii, Oxytropis bella, Astragalus alitschuri, Rhamnus minuta, Hackelia testimudi or even Cousinia rava. Leaves room up to 4400 m altitude to the alpine floor and its grasses based on fescues and Stipa sp. Above the 3800 m, plants must have psychophilic capabilities. Beyond 4500 m is the snowy floor with scarce or even absent dwarf vegetation.

In the eastern part of the massif, the dominant landscape is desert and rocky. At lower altitudes, halophilous species develop such as samphires (Salicornia sp.), Saussurea salsa andPolygonum sibiricum. In the rare humid valleys, Cyperaceae, Scrophulariaceas and Rosaceae form meadows. In the intermediate open steppes, the flora is generally reduced to succulents and cushion plants ( Cushion plant) Acantholimon and Oxytropis; common tansi (Tanacetum vulgare) is also present, as is wormwood (Artemisia absinthium), the astragalus (Astragalus sp.) and garlic (Allium sp.). The species of iris and poas grow in the high steppes of grass. Other plants found in this part of the massif are of Tibetan influence: Krascheninnikovia ceratoides , Eurotia prostrata, Acantholimon diapensioides, Tanacetum gracile, Tanacetum xylorhizum, Tanacetum tibeticum , Carex pseudofoetida, Kobresia sp., Juncus thomsonii, Thylacospermum caespitosum, Christolea crassifolia, Oxytropis chiliophylla, Nepeta longibracteata, Dracocephalum heterophyllum and Pedicularis cheilanthifolia.

The few lakes are home to macrophytes: Potamogeton, Chara, Ceratophyllum, Myriophyllum and Bacillariophyta .

Fauna

Among the mammals found in the Pamir massif, the yanghir (Capra ibex sibirica), the wolf (Canis lupus), the red fox ( Vulpes vulpes), the lynx (Lynx lynx), Pallas's cat (Otocolobus manul), the marten (Martes foina), the alpine weasel (Mustela altaica), the ermine (M. erminea), the Tolai hare (Lepus tolai), the Himalayan brown bear (Ursus arctos isabellinus ), the markhor (Capra falconeri, locally kiik) and the snow leopard (Uncia uncia) in the western part, while the marmot of long-tailed (Marmota caudata), the woolly hare (Lepus oiostolus), the long-eared pika (Ochotona macrotis ), the yak (Bos grunniens), Marco Polo's argali (Ovis ammon polii, locally ar-khar), a subspecies endemic to the Pamirs, are found in the Oriental. The snow leopard and Marco Polo's argali are threatened with extinction. Other carnivorous mammals are present: the golden jackal (Canis aureus), the dole (Cuon alpinus), the steppe fox (Vulpes corsac), the wild cat (Felis silvestris), the European otter (Lutra lutra), the European badger (Meles meles), the steppe polecat (Mustela eversmannii), the weasel (M. nivalis), the Siberian weasel (M. sibirica), the marbled polecat (Vormela peregusna) and the Asiatic black bear (Ursus thibetanus). The wild boar (Sus scrofa), the red deer (Cervus elaphus), the Siberian roe deer (Capreolus pygargus), the Persian gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa ), the great baral (Pseudois nayaur) and the kiang (Equus kiang) complete the large mammals. The insectivores are represented by the Eurasian hedgehog (Hemiechinus auritus), Brandt's hedgehog (Paraechinus hypomelas ), the light gray crocidura (Crocidura pergrisea), the dark crocidura (C. pullata), the garden crocidura (C. suaveolens), the moss dwarf (Suncus etruscus), the endemic species of the long-toothed shrew (Sorex buchariensis), the pygmy shrew (S. minutus ) and the flat-headed shrew (S. planiceps). Also Numerous rodents have been identified: the Himalayan marmot (Marmota himalayana), the Souslik relicta (Spermophilus relictus), the Siberian gerbil ( Allactaga sibirica), Kozlov's salpingote (Salpingotus kozlovi), the gerbil of hairy feet (Dipus sagitta), the Campagnol des montagnes argenté (Alticola argentatus), the Bucha campagnolrian (Blanfordimys bucharicus), the Rat-taupe des monts Alaï (Ellobius alaicus), the endemic Zaysan Rat-taupe (E. tancrei), the highland vole (Microtus gregalis), the Kyrgyz bell ringer (M. kirgisorum), the juniper bell ringer (Neodon juldaschi), the gray hamster (Cricetulus migratorius), the red-tailed merione (Meriones libycus), the southern merione (Meriones meridianus), the pygmy mouse (Apodemus uralensis), the Himalayan field mouse (Apodemus pallipes), the short-tailed rat (Nesokia indica), the Turkestan rat (Rattus pyctoris), the Balkan muscardin (Dryomys nitedula) and the Indian porcupine (Hystrix indica). They are complemented by three additional species of lagomorphs, namely Royle's pika (Ochotona roylei), the red pika (O. rutila) and the desert hare (Lepus tibetanus). Finally, Bats are an important order in which the great bat (Rhinolophus ferrumequinum), the little horseshoe bat (R. hipposideros), Hemprich's long-eared (Otonycteris hemprichii), the Asian barbastella (Barbastella leucomelas i>), Botta's serotina (Eptesicus bottae), common serotina (Eptesicus serotinus), the Vespertilion à moustaches du Népal (Myotis nipalensis), the small southern murin (M. oxygnathus), the medium-sized buzzard bat (M. blythii), the tooth-eared Murin (M. emarginatus), the Fraternal Vespertilion (M. frater), the mustachioed bat (M. mystacinus), the common noctule (Nyctalus noctula), the common bat (Pipistrellus pipistrellus), the mountaineer bat (Hypsugo savii), the common moth ( Plecotus auritus), the gray long-eared bat (P. austriacus), the bicolor bat (Vespertilio murinus), Hutton's murine (Murina huttoni), Schreibers' miniopter (Miniopterus schreibersii ) and the long-tailed bat (Tadarida teniotis).

- Fauna in the Pamires

Snow leopard

Yanghir

Marjor

Yak at Lake Karakul

Argali de Marco Polo

Long tail marmota

Among the birds, the Tibetan partridge (Perdix hodgsoniae), the sandgrouse, appear in the eastern part of the massif. Tibetan (Syrrhaptes tibetanus), the Tibetan picoibis (Ibidorhyncha struthersii), the great Tibetan crow (Corvus corax tibetanus), the horned lark (Eremophila alpestris) and the Himalayan vulture (Gyps himalayensis); the Central Asian gull ( Larus brunnicephalus) and the Indian goose (Anser indicus) also nest near the lakes at almost 4000 m altitude while the Tibetan stonecrop (Tetraogallus tibetanus) prefers rocky slopes; the western jackdaw (Corvus monedula) and the snow sparrow (Montifringilla nivalis) have been seen even at 6000 m altitude. In the western part the Indian oriole (Oriolus kundoo), the Himalayan ptarmigan (Tetraogallus himalayensis), the Greek partridge (Alectoris graeca), the brown shrike (Lanius cristatus) and the Asian long-tailed monarch (Terpsiphone paradisi). In addition to these, the World Wildlife Fund surveys 220 species of birds, among which the most vulnerable or of special concern are the brown pochard (Aythya nyroca), Pallas's eagle (Haliaeetus leucoryphus), the black vulture (Aegypius monachus), the saker falcon (Falco cherrug), the bustard (Tetrax tetrax), the bustard common (Otistarda), the Turkestan pigeon (Columba eversmanni), the European roller (Coracias garrulus), the Xinjiang ground jay (Podoces biddulphi) and the long-billed blackbird (Locustella major).

Tibetan Picoibis.

Himalayan vulture

Tibetan wonder

Nivalan sparrow

Black vulture

Falcon sare

Several species of reptiles have been identified, all of the order Squamates, namely Laudakia himalayana, Hemorrhois ravergieri, Elaphe dione, Natrix tessellata or tessellated snake, Naja oxiana, Eremias nikolskii, Ablepharus deserti, Asymblepharus alaicus, Scincella ladacensis, Gloydius intermedius, Gloydius halys or even Macrovipera lebetina. Some amphibians are found in humid environments, represented by Pseudepidalea oblonga, Pseudepidalea viridis, known as green toad, as well as Hynobius turkestanicus. The only species of fish that flow through the rivers west of the massif, and the lakes, are Triplophysa stoliczkai, Nemacheilus lacusnigri, endemic to Lake Kara-Kul, Schizothorax intermedia, Schizopygopsis stoliczkai , as well as the alien species Coregonus peled and Carassius gibelio, introduced in 1967. The latter feeds in particular on mollusks and crustaceans, as well as chironomid larvae that inhabit bodies of water. Cladocerans are representative of zooplankton.

Unidentified butterflies have been seen above 5700 m altitude on the Vitkovsky Glacier, a tributary of the Fedchenko Glacier. They have also been witnessed in the northern and eastern parts of the massif the presence Parnassius autocrator, Parnassius charltonius, Parnassius staudingeri, Parnassius kiritshenkoi, Parnassius simo, Parnassius simonius, Parnassius jacquemontii, Parnassius actius, from Colias wiskotti, Colias marcopolo , Colias eogene, Colias cocandica, from Sphingidae sp., from Satyrinae sp., from Nymphalidae sp., from Lycaenidae sp. and from Hesperiidae sp.. Aphodius nigrivittis is a species of dung beetle present in yak droppings. Among the other beetles are Bembidion pamirium, Bembidion pamiricola Conophyma reinigi is a species of lobster endemic to desert plateaus; Conophyma birulai, Sphingonotus Caerulans, Sphingonotus rubescens, Sphingonotus mecheriae and Sphingonotus pamiricus are other species of 'orthoptera present in the Pamirs. Anechura fedtshenkoi and Anechura bipunctata are two species of dermaptera. Odontoscelis fuliginosa, Carpocoris fuscispinus, Mimula maureri, Mimula nigrita, Corizus limbatus, Spilostethus rubriceps, Gonionotus marginepunctatus, Geocoris arenarius, Microplax interrupta, Emblethis verbasci, Stenodema turanicum, Chiloxanthus poloi, Saldula orthochila represent the heteropterans. Finally, a large number of hymenoptera and diptera are found in the massif. The surface of the glaciers also houses black spiders, whose species has not been described.

Population

The north of the Pamirs, like the Tian Mountains, is populated by Kyrgyz, a Turkic-speaking ethnic group. The Poches, sometimes nomadic, are also present in the southeast of the massif. and are They are distinguished from the Kyrgyz of the plains under the appellations Burut, Kara-Kirghiz or Dikokamenni Kirghiz. Members of these tribes are yak breeders, sheep and goats.

The Tajiks, who have a language very close to Persian, mainly occupy the western valleys in small scattered villages called kishlaks although a certain Russian presence is observed only in the Jorog agglomeration, at 2200 m altitude, in the heart of the valley of the Piandj, which constitutes up to Rushan the region with the highest density of the massif. These mountain Tajiks generally have a light complexion and claim to be descendants of the ancient warriors of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom. Although the majority of Tajiks are Sunni Muslims, The populations of the Pamirs are essentially Ismaili Shiites of Nizari obedience who recognize the Aga Khan as their imam. There are also isolated Zoroastrian communities in the mountains. The Tajiks of the Pamirs are divided into six culturally similar groups: Shugnanis, Rushanis, Bartangis., Yazgouls, Ishkashimis and Wakhis. Each valley has its own dialect. The Shugnanis, Rushanis and Bartangis, joined in particular by the Sarikolis of the autonomous Tajik Xian of Tashkurgan, are the only ones who speak intelligible dialects among themselves. Shugnani is therefore used as a lingua franca, although attempts at normalization based on the Latin script have been unsuccessfully carried out in the 1920s and 1930s. Since its recognition in 1989, Shugnani Work on transcription into the Cyrillic alphabet has been underway in those languages. Meanwhile, Plains Standard Tajik is used as a literary language. By mid-century XX, some 40,000 people were identified as speakers of a Pamir language, a figure that increased to almost 100,000 in the early 1990s. Outside of Shugnani, the status of Pamir dialects, some spoken by only 1000 speakers, is considered fragile. In addition, the Tajiks of the mountains, culturally similar to those of the Pamir but religiously and linguistically close to those of the plains, populate the west of the massif, mainly the Darvaz district.

Poplar is used in construction and as firewood. The typical Pamir house, locally called chid, is a central feature of the culture of the Pamir people. It includes Indo-Aryan especially Zoroastrian elements. Its architecture rests on old symbols that are 2,500 years old. The walls are made of stone and mortar; The roofs are flat and allow wood and food to dry. The interior offers two rooms: a small one, for meals in summer and for rest, which gives access to a second larger one, organized according to three levels that correspond to the three kingdoms of nature (mineral, vegetable, animal) and the three levels of thought (inanimate, vegetative and cognitive). It is supported by five wooden pillars that correspond to the five pillars and the five members of Ali's family, linked by syncretism with the five Zoroastrian gods and goddesses. Two beams connect two pairs of pillars, symbolizing the material and spiritual worlds. Other groups of beams are present, including six around the hearth representing the six prophets of Islam or the six directions of the Zoroastrian universe, and another seven for the first seven imams or the seven known main stars (Sun, Moon, Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn) or even the seven Amesha Spenta. On the ceiling, an oculus formed by four overlapping concentric wooden squares lets in daylight and symbolizes the four elements. The interior combines the colors red and white, respectively, sources of life and well-being.

Crafts, especially weaving, play an important role in local culture, as do traditional dance and music, played on tamburas, rubabs, setors and riqs. Buzkashi are still practiced in the Murghab district. The Wakhis, who call themselves xik, grow cereals and live between 2200 and 3500 m altitude.

Several of the highest roads in the world cross the Pamirs. Among them is the Karakoram Highway, between the Pakistani province of Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and China, which culminates in the Khunjerab Pass at 4693 m altitude. The second is the M41 route, the trunk of which is called Pamir Highway (Pamirskii Trakt or "Pamir highway or route") in reference to the previous one, but also "drug route", despite the fact that it was not opened to foreigners until 1998 and that controls are frequent. This section connects Dushanbe, in Tajikistan, with Osh, in Kyrgyzstan, crossing the province of Upper Badakhshan culminating in the Akbaitalen pass at 4655 m altitude. The latter is the main supply route for the region; Between Murghob and Jorog, sections of asphalt in poor condition alternate with tracks in relatively good condition. After the latter, access to the north, descending the course of the Piandj, and to the south, leaving the M41 towards Ishkashim, is via a narrow reinforced road. The Yazgoulem, Vanch and Shakhdara valleys are accessible by roads in poor condition. The Kulma Pass, on the border between the People's Republic of China and Tajikistan at 4362 m altitude, in the Sarikol mountain range, was reopened in May 2004 and connects the Karakoram Highway with the M41 from the second half of each month from May to November.

History

Population and opening to the world

About fifty Stone Age sites have been discovered in the eastern part of the massif. More than 10,000 petroglyphs and pictograms have also been identified, which essentially represent religious and animal symbols and poems, some dating back to the Upper Paleolithic. Traces of charcoal from a human hearth in the Pamirs have been scientifically dated to 9500 ago years. In a cave south of Murghab, at 4000 m altitude, parietal representations from the Neolithic appear, recognized as the highest in the world. world. However, unlike the Tian Mountains, no pottery from that period has been found. Kurgans—burial mounds—have been found in the Aksu Valley and are attributed to the Sakas, but their antiquity is still debated. Finally, archaeological remains of tombs covered with wooden logs have been unearthed on the high plateaus of the eastern massif.

Lapis lazulis from the Pamirs were found in the Sumerian era in Mesopotamia and in the Harappan civilization in the 3rd millennium BC. C., and after the 1st millennium BC. C. when in ancient times caravans traveled with precious stones destined for the Egyptian pharaohs. Later, for almost 2000 years, the massif was part of the Silk Road, leaving the ruins of the once imposing fortresses, although the sections that crossed it were only secondary and vertiginous roads. The Han dynasty managed to make the connection between the Amu Daria and the Syr Daria through the massif. Chinese Buddhist monks crossed the Pamirs during their journeys to India, such as Faxian, around the year 400, and Xuanzang in the first half of the century VII. Despite its high mountains and the aridity of the region, the massif was considered a relatively easy area of passage compared to the other surrounding massifs.

Not even the governments of the Greco-Bactrian kingdom, between the 3rd and [[century II a. C.]], neither the Chinese Han and Tang dynasties, nor the expansion of Islam under the Umayyad dynasty, between the 7th and 8th centuries, nor the Tibetans in the VIII, nor the Mongol empire founded by Genghis Khan at the beginning of the XIII, they established permanent settlements in the Pamirs. Only the descendants of the Persian Achaemenid empire, the Tajiks of Bactria and Sogdiana, whose name means "sedentary people", remained in the massif since the 17th century II, while suffering from various subsequent influences..

The first true testimonies of regional history are the work of the Venetian explorer Marco Polo, on the occasion of the crossing of the mountains in 1273-1274 towards Cathay, that is, to China, probably traveling through the valley of Wakhan-Daria and Kashgar, following in Xuanzang's footsteps. He made a summary description, but unique for the time: he addressed the difficulty of the mountain passes to be crossed, the landscapes and geology, the climate, the fauna, agricultural production, the populations, their traditions and their religion. He also reported the existence of ruby deposits. He wrote:

This plateau is called Pamir, and for twelve days there is no village, and it is good for travelers to carry provisions. There are no flying birds for latitude and cold. Fire is not as clear as in other parts due to the intense cold, and things take a long time to cook..TravelMarco Polo

Western exploration and occupation

Due to the fall of the Timurid Empire, the caravan routes became dangerous and no European returned there before Bento de Góis in 1603, which did not provide any really new knowledge about the region. The Kyrgyz investigated the north of the massif around the XVI century, which the Mughals who arrived from the south did not do. Even when in the 18th and 20th centuries the emirates of Bukhara and Afghanistan took control of part of the Pamirs, it was only as sovereigns of the local lords that they paid tribute to them.

Until the last third of the 19th century, the massif, apparently poor in natural resources and until then of little interest geostrategic, it remained a remote, uncoveted place. In 1838 Lieutenant John Wood of the British Indian Navy was sent to search for the sources of the Oxus (now Amu Daria). He ascended the Piandj River and then its tributary the Pamir River until he reached Lake Zorkul, initially called Lake Wood in his honor and then Lake Victoria until 1895. In 1841, he wrote a report titled Journey to the Sources of the Oxus, which earned him a medal from the Royal Geographical Society. However, despite some geographical discoveries, the report was of little interest from the point of view of knowledge of the populations of the massif. Given the difficulty of studying the massif, Thomas George Montgomerie proposed the idea, in 1863, of training and using the services of the natives to map the region within the framework of theGreat Trigonometric Survey The Greek doctor and explorer Panayotis Potagos crossed the massif in 1870.

Problems between the British and Russians: the Great Game

Around that year 1870, the Pamirs and the Karakorams became an area of tension between British India and the then rapidly expanding Russian Empire, in a conflict dubbed the "Great Game." The Russians sent reconnaissance missions to the north and center of the massif, while the southern populations were subdued by the British authorities. In 1873, the British and Russians agreed to establish an Afghan border along the Panj River. The British They tried to persuade the Qing dynasty to extend its territory to the west, to link with Afghanistan, but the Russians beat them to it and eventually ended up occupying the entire massif. The borders were set in 1895 at the level of the Wakhan Corridor, as shown. had been suggested since 1873. The Russian Empire annexed the Emirate of Bukhara's possessions in the massif in 1904.

Meanwhile, a second British mission was launched in 1874 from Kashgar and studied in particular the Sarikol mountain range, around Taxkorgan. In turn, the Russians, from 1871 until around 1893, mounted several Russian military-scientific expeditions that mapped most of the Pamirs (Alexei Pavlovich Fedchenko, Nikolai Severtzov, Captain Putyata and others). It was later visited by Nikolai Korzhenevskiy. Several local groups asked Russia to protect them from the Afghan invaders. The Russians were followed by a number of non-Russians including Ney Elias, George Littledale, the Earl of Dunmore, Wilhelm Filchner and Lord Curzon, who was probably the first to reach the Wakhan source of the River Oxus. In 1891 the Russians informed the soldier and explorer Francis Younghusband that he was in their territory and later accompanied Lieutenant Davidson out of the area ("Pamir Incident"). In 1892 a Russian battalion under Mikhail Ionov entered the area and camped near present-day Murghob. In 1893 a proper fortress was built there (Pamirskiy Post). In 1895 its base was moved to Jorog against the Afghans. In the 1880s-1890s, knowledge increased again, thanks to work done independently by Younghusband and Curzon, but they were regularly expelled by the Russians. The French explorer Gabriel Bonvalot, accompanied by the painter Albert Pépin (who made many sketches), and by the Luxembourgish naturalist Guillaume Capus, as well as by the Russian Bronislav L. Grombtchevsky who supported him, crossed the massif from Och, in the Alaï Mountains, to the Hindu Kush in 1887. His compatriot Henri Dauvergne did the same same the following year and, in particular, reached, in turn, the sources of the Piandj. The Danes, judged neutral by the Russians, were authorized to launch two expeditions led by Ole Olufsen between 1896 and 1899. The accumulated knowledge was They are among the most significant in the region in natural, human and social sciences.

Russian occupation

In 1910, already as a colonel, Pyotr Nikolayevich Krasnov received the appointment as commander of the First Siberian Regiment, located in the region. The first truly scientific expeditions of the century XX happened under the direction of Willi Rickmer Rickmers. The first, in 1913, was from Austro-German, sent at the instigation of the alpine clubs of the two countries. On that occasion, Rickmers unknowingly took the first photograph of the highest point in the Pamirs, Ismail Samani Peak. The second, German-Soviet, expedition was sent to the heart of the massif in 1928. Rickmers was accompanied by Nikolai Petrovich Gorbunov. During that expedition, Karl Wien, Eugene Allwein and Erwin Schneider took the opportunity to make the first ascent of Lenin Peak, from the south face. Also the unknown areas around the Fedchenko glacier were mapped.

Despite the October Revolution of 1917 and a renegotiation of treaties and alliances, the Pamirs gradually fell into Western oblivion. This isolation was reinforced in 1929 when the Soviet Socialist Republic was established in the USSR. Tajikistan and mountain dwellers were called to work in the cotton fields in the southwest. After the construction of the M41 route in 1931 aimed at breaking the isolation of the massif, other Soviet missions followed in the decade. Shortly before the Second World War, the first permanent villages were built in the eastern part of the massif, on the outskirts of Murghob, then known as the Pamirsky Post since its foundation in 1893. The opening of schools and the establishment of kolkhozes (collective farms) can explain this sedentarization.

After the war, Vladimir Ratzek was responsible for mapping the Pamirs, which then remained largely unexplored. At the head of several military expeditions, he took the opportunity to climb the highest peaks of the massif, especially the three over 7000 m altitude. Helicopters They appeared in the 1950s, and facilitated the development of mountaineering. In 1962, Anatoly Ovtchinnikov and John Hunt led a British-Soviet expedition to Garmo Peak, during which Wilfrid Noyce—a member of the first Everest expedition in 1953 with Hunt— and Robin Smith fell to their deaths during the descent. The crampons of the British were not adapted to the soft and unstable snow of the Pamirs. The team slid and could not stop the fall, colliding with a pile of ice and disappearing into a 800 m cliff. Their compatriots decided to bury them at the site of the accident. In 1969, to commemorate the centenary of Lenin's birth, the international mountaineering congress was organized on Lenin Peak. Members from thirteen countries were invited to join the Soviets and participate in a massive expedition, but many of them lacked experience. Quickly, the climbers became disorganized, there were abandonments and accidents, one of them fatal, and the celebration became painful; Despite everything, of the hundred participants, 86 reached the summit, including 30 foreigners. In 1974, a group of eight women climbers were killed during a storm when they were near the summit. In 1990, an avalanche caused by An earthquake hit Camp II and killed 43 European and Russian mountaineers. Only one of them escaped; It was the deadliest accident in the history of mountaineering.

It was not until perestroika, at the end of the 1980s, that the Pamirs were allowed to return to their region, rebuilding their ruined villages and returning to cultivating 4,000 hectares of land left fallow from the 16,000 hectares of arable land. The Afghan war of 1979 to 1989, during which the massif served as a secondary rear base for the combatants, but especially the Tajik civil war of 1992 to 1996, which saw the Pamirians claim some autonomy from the central communist power, plunged the Pamirs back into a zone of tension. The few access roads were destroyed. In the meantime, however, study projects have been launched, in particular by the United Nations University, in agreement with the Academies of Sciences, to support the development of the massif. Proposals are made to protect natural heritage and promote ecotourism.

Activities

The population of the Pamirs obtains their income from a subsistence economy, based on animal husbandry and self-sufficient agriculture, and from illegal activities such as drug trafficking or poaching. Tourism barely manages to develop in the long term and the environment remains relatively preserved due to both the isolation of the massif and the creation of several protected areas.

Economy

Sheep farming on the highland grasslands remains an essential source of income for the region. Its wool is used in particular to make djuraby, socks or stockings – medium to long – woven with three needles by women according to precise customs, with patterns that are both traditional and unique; the wool is dyed with dyes obtained by stirring a thread in plant infusions. The yak, which is native to Tibet and is locally called kuta, can weigh up to 500 kg and is raised for its meat and for its milk which is used to produce cream and yogurt. Its wool and skin are used to make clothing and other utensils. The fermentation of their dung produces fuel. It is used in agriculture as a beast of burden, as it is capable of dragging heavy loads, crossing streams and surviving at high altitude.

Fisheries have great development potential in the Pamir lakes. The species Schizopygopsis stoliczkai represents almost all fish catches, to which are added Schizothorax intermedia and Carassius gibelio. Yields are highly variable due to the artisanal means used and irregular exploitation. In the late 1990s, 180 tons of fish were harvested per year, including 65−94 tons in Lake Yashilkul alone, with Lake Turumtaikul being the largest. productive with 34−40 kg per hectare and average catches of more than eight kilograms. The introduction of the species Coregonus peled could significantly increase production.

In the waste cones and on the alluvial terraces where the towns stand, well drained, vines, apricot trees, apple trees, pear trees, walnut trees and mulberry trees are grown.. The climatic conditions allow for a single annual crop of barley, wheat, potatoes, beans and peas. Populations depend largely on irrigation, especially in the more arid valleys and plateaus of the eastern part. Water is diverted from the most sprayed regions or obtained from melted snow and glaciers. In Tajikistan, since independence, agriculture has once again become a food crop to offset 85% of food imports. Poppy (Papaver somniferum) and hemp (Cannabis sativa) are cultivated illegally. They adapt well to arid conditions and frozen soils. The poppy appeared in the 19th century and was eradicated by the Soviets in the 1940s. Since the independence of Tajikistan, narcotic plants have reappeared taking advantage of the porous borders and ease of conservation, making this activity a financial windfall in the Pamirs. Peat obtained from plants locally called teresken sometimes replaces animal manure in the fuel production. Due to shortages and rising import prices of coal and fuel oil after Tajikistan's independence, as well as the lack of development of renewable energy, teresken is often used as a last resort directly as fuel, which has led to desertification in the eastern part of the massif in the last twenty years.

The west of the massif, especially the Shugnan valley and the adjacent ones, has veins of lazurite (locally called ljadshuar) and ruby deposits that have been exploited respectively since Antiquity and the Middle Ages. Between 500−1000 kg of lapis lazuli were usually extracted on the same day at the end of the century XIX. The seams were exploited again between 1972 and the early 1990s. Coal and lignite were also extracted in small quantities in the west and center of the massif. Sulfur, nitrate, salt and marble could be exploited profitably if infrastructure were developed. The considerable potential for hydroelectric energy is notable and there are modest reserves of oil, uranium, mercury, brown coal, lead, zinc, antimony, tungsten, silver and gold. The industry is very underdeveloped, with production of cast aluminum, zinc, lead, chemicals and fertilizers, cement, vegetable oils, mechanized tools for cutting metals, refrigerators and freezers.

Tourism

Access to the heart of the massif became possible in the second half of the 20th century. In 1978, more than 300 mountain passes or hills had already been crossed and listed by hiking associations, the highest being 5970 m above the level of the sea, the Zimovstchikov Pass between the Fedchenko Glacier and one of its tributaries, the Vitkovsky Glacier, in 1959. The practice of this sport really took off in the Pamirs in the late 1980s and early 1990s. At the same time, the high peaks of the massif are climbed by 200 to 400 mountaineers, mainly Russians, every July. The civil war from 1992 to 1996 in Tajikistan stopped this tourism development.

Since the 2000s, the massif has been opened to international tourism, although a special permit is required and fees are paid to the Tajik authorities. In 2003, 1,500 Trekkers, mainly Westerners, were surveyed by the national tourism agency; In 2006, just over 1,000 people arrived at the Jorog tourist office. This city is home to the second highest botanical garden in the world. The Agency Sayoh has the responsibility of bringing economic benefits to local people, but has been criticized for the difficulties faced by private companies. Domestic, foreign and transnational associations, foundations and institutions have sustained transnational support development efforts. Despite everything, ecotourism struggles to seduce tourists, only 10% of them have visited the Pamir National Park. Mountaineering, whose infrastructure, including rescue services, was damaged by the fall of the Union of Republics Soviet Socialists, is experiencing a beginning of renewed activity, especially from Kyrgyzstan. Argali hunting continues with prices reaching 30,000 euros per head, with a considerable lack of transparency, but whose revenues could exceed those of the fees collected by the authorities.

Security

Check the geopolitical and security conditions in Tajikistan before traveling. Although the country is relatively stable, some regions, such as the Karategin Valley (Garm) in the center of the country, are becoming discouraged. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs strongly recommends avoiding the borders with Uzbekistan and Afghanistan.

Central Dushanbe is the least dangerous area in the country. Crime is common, you have to be careful. Precautions should be taken when traveling to border areas, as there are still territorial disputes and in some cases the area contains antipersonnel mines.[8]

Environmental protection

The Pamir (or Pamirsky) National Park, also known as the Tajik National Park, was established on January 26, 2006, after having been envisioned since 1992. Protects 12,260 km², just over 8% of the area of Tajikistan. It includes in its statutes a nature reserve that plays the role of a buffer zone and increases the surface of this protected area to 26,000 km², turning it into the largest in Central Asia. In 2008, it was included in the tentative list of Tajikistan as a preliminary step to integrating the UNESCO World Heritage list and that candidacy was approved in 2013, based on the remarkable natural landscape (including Ismail Samani Peak, Fedchenko Glacier and Sarez Lake), in the unique biome characterized by an arid climate, at high altitude (making it the third highest World Heritage Site after Everest and Nanda Devi), in being an important hydrological reserve and having a unique relief. This recognition could be accompanied by a relaunch of tourist visits.

The Dashtidjum (or Dashtidzumsky) state nature reserve, located in Tajikistan, southeast of the Khazratisho ridge and north of the Piandj River on the western bank of the Pamirs, is a zapovédnik, a comprehensive reserve, that is, the highest level of protection among protected areas. A natural refuge (zakaznik) had previously been established in 1972 on 533 km², before being complemented by the complete nature reserve over 197 km² in 1983. There is a project that aims to add 267 km² buffer zone to the natural refuge to increase its area to 800 km². A Since 2007, an important area for the conservation of birds has completed the network of protected areas of Dashtidjum in an area of 378 km².

The Zorkul (or Zorkylsky) State Nature Reserve is located around the homonymous Lake Zorkul, along the border with Afghanistan. It was created in 1972 with 165 km² as a natural refuge before being promoted into a comprehensive reserve in 2000 and expanded to more than 877 km². It contains a Ramsar site since 2001, as well as an important bird conservation area and aims to be included in the UNESCO World Heritage list.

Five other natural refuges are located in the Tajik part of the Pamirs, whose main objective is the conservation and reproduction of fauna and flora, in particular the yanghirs and the Marco Polo argalis that are hunted for their horns. They are:

- the natural shelter Sanvor (or Sangvorsky), also called Sanglyar (or Sanglyarsky), which is in the chain of Pedro I. It was created in 1970 (or 1972) and spreads over 509 km2.

- the natural shelter of the Pamir, which includes Lake Kara-Kul 5000 km2; It includes the Ramsar site of the wetlands of Lake Kara-Kul.

- the natural shelter of Muskol (or Muzkulsky), which is in the chain of the same name and covers since 1972 an area of 669 km2;

- the natural shelter Verkhniy Muzhkul is east of the latter;

- the natural shelter Ishkashim, which is at the southwest end of the Pamir, in the elbow formed by the Piandj;

To top it all off, another Ramsar site protects the Shorkul and Rangkul lake wetlands.

And in Afghanistan, the Pamir-i-Buzurg wildlife reserve is located at the western end of the Selsela-Koh-i-Wākhān mountain range, on its northern slope. It was created in 1978 and has the same level of protection than the natural refuges of Tajikistan. In the People's Republic of China, in eastern Xinjiang, the Taxkorgan nature reserve protects 14,000 km², part of it in the southeastern reaches of the Pamirs. It houses wolves, great bharals, some Himalayan brown bears, 150 specimens of Marco Polo's Argali and 50 to 75 snow leopards. It is populated by 7,500 inhabitants who hunt ungulates for food and carnivores to protect more than 70,000 domestic animals. Maintains an adequate level of protection.

Culture

When God created the world and distributed the lands, the representative of the Pamirs was so discreet that he seemed to be forgotten and that is why he was very sad. God was so sorry that he attributed to him the Badakhshan that he wanted to keep for him as his own garden.

Some authors place the biblical Eden and Mount Ararat in the Pamirs, where Noah would have set foot after the great flood.

According to a legend, Pamir and Alitshur would be two brothers who would personify the Great Pamir and the Pamir Alitshur, both adjacent.

Chinese Buddhists imagined that one of the Pamir lakes was inhabited by a large poisonous dragon. They also believed that its greenish-black waters are full of turtles (rouen), sharks (kiao) and crocodiles (tho). In the old days, when some passing merchants set up camp for the night near the lake, the angry dragon, He killed the merchants with magic words. When the king of Pan-tho (or Ko-pan-tho) was informed, he entrusted his authority to his son and went to the kingdom of Ou-tchang, where he studied the magical words of the Brahmins. Having conquered that science in the space of four years, he returned and regained royal authority. In turn, he cast his magic words against the lake dragon. He became a man and, full of repentance, went to look for the king. The king shortly exiled him to the Tsung-ling Mountains, two miles li (200 leagues) from that lake.

Ismaili tradition says that the philosophers Nasir e Khosraw and Tolib Sarmast were sent to the Pamirs to make it habitable in the Middle Ages. They built trails on the mountain slopes. Tolib died and was buried in the Rushan, where two gigantic bananas grow that would have grown from the canes of the two men planted in the ground for 900 years. Nasir, continuing his journey, found himself thirsty. When an old woman refused to serve him water, he planted his staff in the ground from which a spring sprang up that still flows today. Later, a dragon tried to devour him, but Nasir prayed and the dragon turned into a rock, still visible near Ishkashim.

According to another legend, the Pamir Alitshur was once so fertile that rice grew there. When Ali ibn Abi Talib spread Islam in the Pamirs, the inhabitants of this valley refused to convert. Ali cursed and swore that no more grain would grow there. Alitschur would mean the "scourge of Ali" or the "desert of Ali." Only one pond with crystal clear water remains, called Ak-balik (literally, the "white fountain"). It is home to large fish, but anyone who tries to catch them will always be hit by bad luck.

Thus, the massif houses numerous altars and sacred sites. They are surrounded by many stories, natural myths or myths related to saints. Sometimes they act as protection and offerings are placed in them. They are generally made of engraved stones and yanghir or argalis horns. The Pamirs were one of the theaters of Soviet cinema, at a time when there was still a largely unexplored region. Thus, in 1927 the director Vladimir Erofeev, a specialist in the ethnographic genre, filmed the film The Roof of the World: Expedition in the Pamir (Kryša mira: ekspedicija na Pamir), where he followed the geologists. The following year, Vladimir Adolfovitch Chneiderov participated in an exploration that he immortalized in the film The Pedestal of Death (Podnožie smerti ). In 1935, he was inspired to make Djoulbars, a classic Stalinist-era adventure that tells of the heroic fight between a Russian border guard and her dog against a group of Central Asian bandits in the borderlands. mountainous and snowy mountains of the Soviet empire.

References and notes

- Notes:

Contenido relacionado

Machu Picchu base

Wadati-Benioff zone

Alcazar of San Juan

Andes mountains

Periglaciate