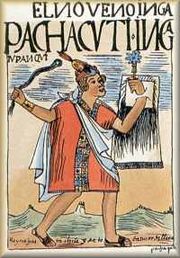

Pachacutec

Pachacútec Inca Yupanqui Cápac Intichuri (from Quechua: Pacha Kutiq Inka Yupanki Qhapáq Intichuri, «Inca of the change of the course of the earth, worthy of esteem of the Sovereign son of the Sun", born with the name of Cusi Yupanqui (Cuzco, ca. 1400-Cuzco, ca. 1471) was the ninth ruler of the Inca state and who converted it from a simple curacazgo to a great empire: the Tahuantinsuyo.

His wife was the ninth coya, Mama Anahuarque, a native of Ayllu Chocco. His father, Huiracocha Inca, appointed him as his successor around 1438, after victoriously leading the military defense of Cuzco against the invasion of the bellicose Chanca army.

As part of his vision as a statesman and warrior leader, he conquered many ethnic groups and states, highlighting his conquest of Collao, which increased the prestige of the Incas and particularly of Pachacútec, who due to the notable expansion of his domains was considered an exceptional leader, bringing to life epic stories and glorious hymns in tribute to his exploits. Numerous curacas did not hesitate to recognize his skills and identify him as Son of the Sun (in Quechua, Intiq Churin ).

While he was still alive, his son and successor Túpac Yupanqui defeated the Chimú kingdom and continued the expansion of Tahuantinsuyo. In addition to being a conqueror, warrior, and emperor, various chronicles state that he was also a great administrator, planner, philosopher, observer of human psychology, and a charismatic general.

Pachacútec is the first Inca of which there are historical references that corroborate his existence, for which he is recognized as the "first historical Inca", however, the relevance of his figure and legacy, as well as that of his name, leads to think to several scholars that it has a much greater importance than that of just one character, coming to represent the beginning of a whole period of transition and restructuring for the Inca society, a stage of changes that would continue after his death in 1471, due to his son Túpac Yupanqui and his grandson Huayna Cápac.

Biography

Origin

He was the son of Huiracocha Inca and Mama Runto; and his original name was Cusi Yupanqui, whose meaning is “Blessed Prince.” He was born in Cuzco, in the Cusicancha palace or “House of Joy”, bordering the Coricancha temple. His tutor Micuymana was the one who taught him history, laws and language, as well as the handling of the quipus.

From a very young age he was admired by the Inca nobles, because he had the courage, intelligence and maturity that his brother Inca Urco (who had been named successor of Huiracocha Inca) needed so much, in the same way he showed aptitudes for government and the conquests, which his brother lacked in the same way. Upon fulfilling the warachikuy rite, Prince Cusi Yupanqui took part in military companies, under the direction of generals Apo Maita and Vicaquirao. Sarmiento de Gamboa refers that "his bosses had good hope of him because of the courage he showed in his flowery adolescence."

It is said that the Inca nobles advised Huiracocha to name Pachacútec as his heir, but Huiracocha had become so fond of Inca Urco that he always preferred him to anyone else. When Huiracocha decided to retire to the Yucay Valley, he sent the tassel or mascapaicha (symbol of Inca royal power) to Urco, who thus took over as ruler of the Cuzco Confederation. However, Urco, instead of fulfilling his political role, fell into laziness and spent his time in amusements and vices.

Conflict with the Chancas

Around 1430, the Chancas invaded. They were already in Vilcaconga, when they sent their emissaries to Cuzco to demand the surrender of Huiracocha Inca. This, already old and fearful of the power of the invaders, replied that he agreed to submit and that he wanted to meet with the Chanca chief. Immediately afterwards, Huiracocha and his son Inca Urco fled from Cuzco and took refuge in the fort of Caquia Xaquixahuana, to the surprise of the Inca ethnic group, who then placed their hope in the young prince Cusi Yupanqui, who received the support of the generals Vicaquirao and Apo Mayta to organize the defense of Cuzco.

Cusi Yupanqui asked his father to return to lead the defense of Cuzco, but upon receiving his refusal, he made a general call to the neighboring ethnic groups to resist the Chanca threat together. The Canas were the only ones who allied themselves with the Incas, while on the other hand, the Ayarmacas were the only ones who supported the Chancas; the other ethnic groups waited to see the side that victory would fall on to join him.

The first battle was in Cuzco, where the soldiers of the Inca army won, favored by the spectator ethnic groups, who joined them as soon as they began to win. Then, in Ichubamba, the Inca victory was accentuated, giving rise to the legend of the stone soldiers.

Once the Chancas were defeated, the Incas prepared the celebrations in Cuzco to which Huiracocha was invited by Pachacútec; However, Huiracocha refused to collect the fruit of the victory, since he considered that Urco should do it, since he was the correinant at the time of the Chanca invasion. Obviously, neither Pachacútec nor anyone wanted to receive Urco. Motivated by envy, Urco organized a small army and marched to Cuzco to overthrow Pachacútec, but the latter, skilfully prepared, defeated him. Inca Urco was wounded by a stone in the throat, was captured and dismembered. His remains were thrown into the Tambo River, while Huiracocha returned to his country refuge in Calca and did not want to return to live in Cuzco.

Girdling of the mascaipacha

When Inca Urco died, Cusi Yupanqui was the only candidate to assume the government of the Cuzco confederation. Preparations began for the ceremony in which the prince would put on the mascapaicha. At Cusi's request, a delegation of orejones went to Calca in search of Huiracocha Inca to request and beg that he go to Cuzco to deliver the mascapaicha to the new leader; in this way he would amend the dishonor of having abandoned the capital in full conflict against the Chancas.

"...and such chief caciques went from there rights where Huiracocha Inca was and told him how Inca Yupanqui sent them there to see what was served, that they might serve him; and as Virachoca Inca saw them before themselves and so great multitude of lords and so much power, I rejoiced much of it (...). After distributing glasses of chicha and portions of coca, rise on foot Huiracocha Inca and consider that since his son sent him those lords and they loved him so much and loved him for lord, it was just that he also encouraged them. He gave them a certain prayer, for which he thanked them for what they had done for him and for his son, and who already knew (...) that he had been lord of the Cuzco there, and that he had gone out of him for causes which they moved him; and that henceforth Inca Yupanqui, his son, should be Lord in the city of Cuzco."Taken from Suma and narration of the Incasof the chronicler Juan de Betanzos.

Numerous llamas loaded with offerings began to arrive at the city of Cuzco from neighboring towns and even from further away. Countless baskets of coca, herbs, and aromatic resins were brought from Anti; From the Yungas, for their part, came shells used in sacrifices, as well as red peppers and rocotos that would be used to season the royal banquet.

As the day of the ceremony approached, the curacas and invited Confederate nobles made their entrance into the capital with great lavishness surrounded by their retinue. Each of the visitors brought beautiful gifts as a sign of recognition, among which were colorful litters, decorated queros, soft blankets, precious metals, and exotic plumeria.

The expected day arrived, after the priests led by the willac umu made a series of sacrifices and prayers, including the immolation of one hundred children as part of the ritual known as Cápac Cocha , the Inca Huiracocha himself proceeded to place the royal tassel on the head of the young Cusi Yupanqui, naming him from then on as Pachacútec Yupanqui Cápac Intichuri, that is, "son of the Sun who transform the world."

Once invested as an Inca, Pachacútec determined that his father Huiracocha should be the first to pay homage to him. For this, the old Inca had to drink a pot full of chicha until it was empty. Without any objection, Huiracocha complied with what was ordered and, when finished, bowed down asking for forgiveness for having abandoned Cuzco in the middle of the war. Pachacutec, always respecting the rank of the old man, and at the same time as his son, helped him to sit up immediately.

Government (1438-1471)

According to information collected by various chroniclers, historians commonly accept that Pachacútec's rule began around the year 1438 and ended with his death around the year 1471. During his rule, he consolidated the Inca Curacazgo in the face of threats from towns premises and transformed it into the Tahuantinsuyo, beginning an imperial era for the Incas. He carried out several conquering expeditions and commissioned others to his brother and son respectively. For all this, his government is recognized as one of the most successful in the history of pre-Columbian America.

Start of imperial expansion

Like his predecessors, the first activity that the new Inca had to carry out was to face a rebellion, this time organized by the Ayarmaca descendants of Tocay Cápac. A fierce battle took place in Huanancancha, but the superiority of the Inca army gave victory to Pachacútec, who, determined to definitively annihilate the insurgents, devastated the enemy towns, decimating a large part of their population. After this defeat, the dangerous chiefdom of the Ayarmacas would not recover its former power. The Ayarmaca sinchi was taken as a prisoner to Cuzco, where he spent the rest of his days locked up in prison.

During the first months of his government, Pachacútec had to subdue several neighboring sinchis from Cuzco: Páucar Ancho and Tocari Topa from Ollantaytambo; Ascaguana and Urcocona de Huacara; and Alcapariguana from Toguaro. Unlike the wars carried out in previous reigns, these military campaigns represented a real effort to consolidate a territorial unit, a predominance of the cusqueños over their comparcanos. The numerous wars that he would sustain in the future would allow him to acquire an enormous territorial extension.

First Conquering Expedition

Once the neighboring curacas were subdued, Pachacútec decided to organize an expedition to the old Chanca territories. Commanding more than 40,000 men, transported on a litter, the Inca headed towards the Apurímac River. Upon reaching Curahuasi, 26 leagues from Cuzco, he delivered a palla from Cuzco to the chief or sinchi chanca Túpac Uasco. With this act, Pachacútec achieved the adhesion of the sinchi. The expedition continued towards Andahuaylas, where, after a meeting of the Orejones council, it was decided to advance towards the territory of the Soras. The resistance offered by the Sinchis Guacralla, from Soras, and Puxayco, from Chalco, was easily defeated. The Soras and Rucanas fled to the vicinity of the Vilcas River and took refuge on a rock.

Pachacútec established his headquarters in Soras and remained there all winter, as the rains prevented him from continuing. After the winter, two Inca armies left: the one under the command of Cápac Yupanqui (brother of the Inca), who headed towards the coast to conquer the lordship of Chincha; and the other under the command of Apo Mayta, to encircle the Soras and the Vilcas who took refuge in the Vilcas rock. About these military campaigns carried out by the Pachacútec generals, there is much confusion among the chroniclers, and it is not possible to make a chronological correlation of the events.

After spending some time in Soras, Pachacútec built his headquarters and moved towards Huamanga, conquering all the towns he visited along the way. The next objective was Vilcashuamán, an important center in the region. When he arrived at this place, Pachacútec ordered the construction of a Temple of the Sun and several buildings. In this way, the settlement became an important administrative center.

Once the entire region of the Chancas and their confederates had been dominated, the return to Cusco lands was undertaken. Before reaching the capital, the Inca had to subdue the sinchis Ocacique and Otaguasi, lords of the town of Acos, located ten leagues from Cuzco. In retaliation for having been wounded in the head during the confrontation, Pachacútec exiled the survivors and relocated them in the Huamanga district, where the town of Acos is today.

Expedition to Collasuyo

Approximately ten years had passed since the coronation of Pachacútec, when the old Inca Huiracocha died in his residence in Calca. In honor of his rank, Pachacútec organized a solemn burial. The body of the deceased Inca was carried on a litter through Cuzco carrying his royal arms and insignia. The funeral procession moved to the rhythm of the slow rumble of the drums, whose sound marked the passage of dozens of warriors.

Shortly after, Pachacútec restarted his expansionist military campaign, sending a group of soldiers under the command of Apo Conde Mayta to the border with the collas, a powerful group whose lord was Chuchi Cápac, also known as the Colla Cápac. Pachacútec did not take long to join these advanced troops, entering enemy lands until reaching the foot of Vilcanota.

When Colla Cápac found out about the Inca incursion into his territories, he went with his armies to the town of Ayaviri to wait for the Cuzqueños. Upon reaching this town, Pachacútec was able to verify that a peaceful submission would not take place, for which reason a long battle began. As the fight dragged on, fearing defeat, the collas withdrew towards Pucará, to where they were pursued by the Incas. In Pucará, a second confrontation was fought, from which not only the cusqueños emerged victorious, but they also managed to take the powerful Colla Cápac prisoner. Once the triumph was assured, Pachacútec headed to Hatun Colla, home of the defeated curaca, where he remained until all the subordinate towns came to pay him allegiance.

After small fights with the inhabitants of Juli and the Pacasas, Pachacútec managed to dominate all of Collao, leaving garrisons and a governor general there. His next destination was the territory of Condesuyos: his conquests took him through Arequipa and Camaná. Finished this, he returned to Cuzco via Chumbivilcas.

There were also uprisings by some subjugated towns. While in the town of Cuyos, Pachácútec was the victim of an attempt on his life. A potter approached him and hit him hard on the head, leaving him injured, although not seriously. The attacker was arrested and under torture confessed to having acted on the orders of the curacas or caciques of Cuyos. These were captured and executed. The town of Cuyos was devastated. Another important event that occurred at this time was the birth of Prince Túpac Yupanqui, son of the coya Mama Anahuarque.

Expeditions commissioned by Pachacútec

After the victory over the Chancas and Collas, Pachacútec's legislative and administrative obligations kept him in Cuzco, so he had to entrust his subordinates with the following conquering expeditions of the Inca Empire, while he was in charge of the remodeling of Cuzco and the consolidation of the imperial government.

The first of these expeditions was entrusted to his brother Cápac Yupanqui towards the Chinchaysuyo territories, and the rest to his son and successor Túpac Yupanqui both to the north and south of the empire. With these conquests, the Tahuantinsuyo would reach its maximum expansion and best consolidation.

Cápac Yupanqui expedition to Chinchaysuyo

The conquest of Chinchaysuyo or the northern provinces was entrusted to General Cápac Yupanqui, who had already excelled in the conquest of the coastal domain of Chincha. He had the collaboration of the Chanca warriors, under the command of Anco Huallu.

Cápac Yupanqui's army marched north, following the Andahuaylas route. They besieged the Urcocollac fortress, to the north of Huamangas, where a group of locals reluctant to Inca domination had taken refuge. But two successive attacks by the Cuzqueños failed miserably. Until a third attack, entrusted to the Chancas, managed to take the fortress. This provoked the jealousy of the Cuzqueños, who feared that the Chancas would become emboldened and rebel against their authority, so they informed Pachacútec of the fact. For now, they continued together with the conquering campaign.

The next rival of the Inca army was the Huanca nation, from the Mantaro Valley (current city of Jauja). Cápac Yupanqui offered them peace in exchange for submission, but the Huancas refused and resisted bravely. Finally they were defeated, although the Inca general was magnanimous and released the prisoners, as well as forbade his troops to engage in looting.

Then, the Inca army subdued Yauyos, Huarochirí and Canta (Atavillos). He continued his advance towards Bombón, where Junín Lake is located (where they met no resistance and limited themselves to harvesting the abandoned crops); and towards the area where the current city of Tarma is located (whose inhabitants, seeing themselves in a military inferiority, submitted).

While en route to the north, to the region of Huaylas (present-day Ancash), Cápac Yupanqui received Pachacútec's answer regarding the Chancas: the order was to exterminate them all. The Chancas found out about the message and at midnight they broke camp and fled into the jungle region, where their ancestors came from.

In Huaylas, Cápac Yupanqui defeated the confederate ethnic groups of Huaylas, Pincos, Piscopampas, Huaris and Conchucos, but not before building the Maraycalle military dairy farm. After the Inca defeated a southeastern faction, he advanced north toward the Yanamayo River, where he was attacked and forced back to high ground. He chose the heights of Yauya for its strategic location, where he built a military tambo. From this point, he directed the sieges to all the populated centers of the region. The confederates had advantages over the cusqueños due to the elevated location of their fortresses that made them impregnable. After half a year of battles, the Incas managed to defeat the rebels.

In pursuit of the Chancas, Cápac Yupanqui arrived near Cajamarca, capital of Guzmango Cápac, the lord of the Cajamarcas. He allied himself with the Chimú Cápac, lord of the Chimúes of the coast, and faced the Incas. But Cápac Yupanqui, appealing to cunning, captured the two lords, and finally defeated the allied armies. The booty that the Incas collected was fabulous. Cápac Yupanqui was proud, and he went so far as to say that he had acquired greater trophies than his brother, the Inca. This slip, added to the fact that he had exceeded his limits in many of his functions, determined that Pachacútec sentenced him to capital punishment. Cápac Yupanqui was hanged, although it has not been determined if he was sentenced or if he killed himself.

Expeditions under the command of Túpac Yupanqui

Around 1460, when Pachacútec was 60 years old and had reigned for almost 30 years, he appointed his son Prince Amaru Inca Yupanqui as correignant. But he was more attached to peaceful activities, at a time when the Inca empire was forged based on military conquests. His lack of military qualities became apparent when he was tasked with suppressing a Colla rebellion. This provoked criticism from the nobles, so Pachacútec decided to separate Amaru Yupanqui from the reign. In his place the other prince Túpac Yupanqui was elected, who was 18 years old at the time.

Túpac Inca Yupanqui was the opposite of his brother. From an early age he demonstrated great warrior skills. Immediately, he led a military expedition to the Chinchaysuyo to annex more territories. The effective command was held by three generals, Tilca Yupanqui, Auqui Yupanqui and Túpac Cápac, all sons of Pachacútec.

Although the region between Cuzco and Cajamarca had already been annexed to the empire, there were still isolated pockets of resistance. One after another, Túpac Yupanqui reduced them. Arriving at Cajamarca, where he established his headquarters, he turned his sights towards the Chimú kingdom. Knowing that it was difficult to attack Chan Chan, the Chimú capital, through the sandbanks of the coast, he elaborated an accurate strategy: go down the Andean ravines and cut off the city's water supply, diverting the course of the torrents. As Chan Chan was in the middle of the desert, it did not take many days to announce his surrender.

Then, Túpac Yupanqui went to conquer the Chachapoyas, warrior people who put up a tenacious resistance, but who ended up being subdued. In another sortie, Túpac Yupanqui marched to conquer Cutervo, Huambo, Chota, possibly reaching Huancabamba.

After the first expedition to the north, Túpac Inca Yupanqui returned to Cusco with numerous booty and taking many Chimú goldsmiths and artisans to teach these arts in the capital. He rested there for two years, and immediately went north again, he conquered the guayacondos, the bracamoros, the avocados, the cañaris. Thus he reached the land of Quito-Carangue. He founded Tomebamba (where his son, the future Inca Huayna Cápac, was born) and built the Quinche fortress near Quito. Four years had elapsed since he left Cuzco, but despite the fact that he was required in the capital, he began another campaign of conquest in the north, on the coast of present-day Ecuador, between Manta and Guayaquil, where he defeated the Chonos, Huancavilcas, and Puna. and patches.

The coastal peoples of Manta were expert navigators, who went out to sea on wooden rafts. Túpac Yupanqui found out through them about the existence of mysterious islands called Ahuachumbi and Ninachumbi, brimming with riches. Excited by this news, the young Inca organized a large fleet of rafts, which left Manta to discover these islands. The chronicles of Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa and Miguel Cabello Balboa recount the success of this expedition. The mysterious islands that Túpac Inca Yupanqui arrived at have been identified with the Galapagos Islands, Easter Island and even distant Polynesia.

Victorious and with abundant booty, Túpac Inca Yupanqui began his return to Cuzco, from which he had been absent for six years. His father, the already old Inca Pachacútec, came out to receive him in Vilcaconga. Both entered the imperial capital triumphantly, amid shouts of joy from the people.

Imperial consolidation and renewal of Cuzco

While his son Túpac Yupanqui was in charge of the conquering expeditions, Pachacútec took charge and continued with the remodeling of the capital of the empire: the city of Cuzco. As the population of the capital increased, the demands for housing, food and primary needs also increased, for which Pachacútec undertook a series of construction and agricultural works: the formation of new neighborhoods, their distribution in lots and the erection of new plazas. and courts; the Inca had several areas around Cuzco depopulated so that they could be used as planting fields, relocating their occupants to areas with a similar climate. In the same way, agricultural production was intensified thanks to the creation of canals in the city of Cuzco, better water distribution, new storage systems and the construction of platforms.

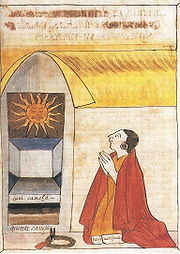

The rebuilding of the Temple of the Sun or Inticancha can be considered his first great architectural work: the humble building of his ancestors was transformed into a temple full of riches; the structure was repaired with lithic blocks obtained from the quarries of Salu, five leagues from Cuzco; Due to all the new sumptuousness of the palace, it became known as Coricancha (Gold fence).

"And when the house was seen by him (Pachacútec) the place where it seemed to him that the house should be built, he commanded that there be a cord, and being brought unto him, they lifted up themselves from the place where he and his own were, and being already in the place where the house was to be built, he himself by his hands with the cord, and brought the house of the sun; and having imagined it was thereTaken from Suma and narration of the Incasof the chronicler Juan de Betanzos.

Another of the most important changes made by Pachacútec was the division of the growing empire into four of his own, having the city of Cuzco (navel of the world) as its center; to the east the Antisuyo, to the west the Contisuyo, to the north the Chinchaysuyo and to the south the Collasuyo.

Death and Succession

He died naturally at the height of the empire, he was recognized and valued as the greatest Sapa Inca for his contributions to the expansion and consolidation of the nascent Inca Empire. His mummy was carried in the tiana or her seat, carried by the great lords to the Aucaypata square, where homage was paid to him. The royal funeral began with the meeting between the mummies of Pachacútec and Huiracocha Inca, his father. The deceased sovereign was dressed in sumptuous blankets and gold and silver ornaments, as well as a feather headdress and a coat of arms. Finally, his mummy was placed in the center of Tococache (now the San Blas neighborhood in Cuzco) in a temple dedicated to thunder that he himself had built.

The succession in command of the Inca Empire was assumed by his son, Túpac Yupanqui, with whom he had co-ruled in recent years and who had shown great warrior and conquering prowess in the expeditions that Pachacútec had commissioned so much north and south of the imperial territory. In this way, without any objection, Túpac Yupanqui would put on the mascaipacha and would fully assume the government of Tahuantinsuyo, after the death and royal obsequies of his father.

Works

Transformation from Kingdom to Empire

Thanks to Pachacútec, the Inca domains ceased to constitute a simple kingdom to form the Tahuantinsuyo, a State that managed to dominate and control politically, militarily and economically other states and chiefdoms located in the vicinity of the Andes. This transformation came from the victories obtained against various states that initially surrounded the Inca kingdom: mainly the Chanca confederation and the Ayamarca lordship.

System of mitimaes and Quechuization

Pachacútec was also responsible for the implementation of the system of mitmakuna or mitimaes -transfers- throughout the Tahuantinsuyo. These were human groups displaced by the State to any point conquered by the Inca in order to fulfill specific tasks that would structure and unite the empire. The mitimaes colonized, brought with them the techniques and methods of production from Cusco, taught the laws and customs, and spread the religion of the Incas. They also carried out control work on the populations recently incorporated into the Tahuantinsuyo. Its function was to produce the basic elements that covered the needs of the subjects and to reproduce the cultural traits with the aim of quechuizar the newly incorporated.

Architecture and urbanism

From the point of view of urban and architectural achievements, Pachacútec ordered the channeling of the Saphy and Tullumayo rivers, which frequently flooded the city of the Sun, Cuzco.

He also rebuilt and decorated with great wealth the sanctuary of Inticancha or enclosure of the Sun, whose name he changed to Coricancha, which means "enclosure of gold". The first Inca emperor restored the palace of Pomamarca or Ciudad del Puma, and that of Patallacta, where he died, in Carmenca. Finally, he planned the construction of the temple-fortress of Sacsayhuamán, located to the north of the city of Cuzco, the same one that began to build his son Túpac Yupanqui and finished his grandson Huayna Cápac, father of Huáscar and Atahualpa. Some historians also attribute to him the arrangement of the Acllahuasi in Cuzco, and the planning and construction of the citadel of Machu Picchu.

Mummy and Legacy

Like all Inca royalty, her body was mummified and preserved for many years, even after the conquest of Peru. The last known place to have housed his remains was the old Hospital Real de San Andrés in Lima, Peru.

The figure of Pachacútec, given the implication and connotation of its title in Quechua: he who transforms the world, has been the subject of innumerable discussions according to the vision mythical and idealistic that is had on him and the consolidation of the Inca Empire, for the Andean vision.

Other historians emphasize his historical figure and tend to consider him as one of the main figures in the development of pre-Columbian civilizations as, for example, the British historian Clements R. Markham would say of him: «The greatest man than the race native of America has produced"; other historians and chroniclers compare his figure with that of an American Charlemagne, referring to the expansion of the Inca State and the consolidation of the empire that he achieved; and even that of Solón, emphasizing the skills of legislator and statesman that Pachacútec is said to have had.

Peruvian composer José María Valle Riestra (1858) composed the symphonic poem Pachacutec: Inca fantasy, in honor of the Inca immortal.

"With its measures it gave geographical and idiomatic unity, beginning the uniformity that later allowed the formation of the current Peru. »Taken of "History of Tahuantinsuyo", historian Maria Rostworowski.