Otto von Bismarck

Otto Eduard Leopold de Bismarck-Schönhausen, Prince of Bismarck and Duke of Lauenburg(in German): Otto Fürst von Bismarck, Graf von Bismarck-Schönhausen, Herzog zu Lauenburg, pronounced/хtoto build f n шb stormsma/k/(![]() listen)) born Junker Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, better known as Otto von Bismarck (Schönhausen, April 1, 1815-Friedrichsruh, July 30, 1898) was a German statesman and politician, the architect of German unification and one of the key figures of international relations during the second half of the nineteenth century. During his last years of life, he was supported by the "Iron Chancellor" for the determination with which he pursued his political objectives, mainly the creation and maintenance of a system of international alliances that ensured the supremacy and security of the German Empire.

listen)) born Junker Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, better known as Otto von Bismarck (Schönhausen, April 1, 1815-Friedrichsruh, July 30, 1898) was a German statesman and politician, the architect of German unification and one of the key figures of international relations during the second half of the nineteenth century. During his last years of life, he was supported by the "Iron Chancellor" for the determination with which he pursued his political objectives, mainly the creation and maintenance of a system of international alliances that ensured the supremacy and security of the German Empire.

He studied law and, from 1835, worked in the courts of Berlin and Aachen, an activity that he abandoned three years later to dedicate himself to the care of his territorial possessions. In 1847 he became a member of the Prussian parliament, where very soon he became the leader of the conservative wing. He harshly faced the revolution of 1848 and at that time began to outline what would be his main political objective: the unification of Germany and the creation of the Reich from authoritarian and anti-parliamentary precepts. In 1862, after being appointed Minister-President of Prussia, he undertook an important military reform that allowed him to have a powerful army to carry out his plans for German unification.

In 1864 he managed to wrest the duchies of Lauenburg, Schleswig, and Holstein from Denmark and, two years later, after the war with Austria, he managed to annex Hesse, Frankfurt, Hannover and Nassau, which gave rise to the creation of the North German Confederation, with Bismarck as chancellor. Finally, the war with France led to the accession of Bavaria, among other states, and in 1871 the Second German Empire was proclaimed at the Palace of Versailles in Paris. Bismarck he became minister-president of Prussia and chancellor. During the nineteen years that he remained in power, he maintained a conservative policy, initially confronting the Catholics and combating the Social Democracy. He was also the organizer of the Triple Alliance, with Italy and Austria-Hungary, created in 1882 to isolate France.

Bismarck's domestic policy was supported by a regime of authoritarian power, despite the constitutional appearance and universal suffrage intended to neutralize the middle classes (Federal Constitution of 1871). Initially he governed in coalition with the Liberals, focusing on countering the influence of the Catholic Church (Kulturkampf) and on favoring the interests of the large landowners through a free trade economic policy; in 1879 he broke with the Liberals and he allied himself with the Catholic Center Party, adopting protectionist positions that favored German industrial growth. In that second period he focused his efforts on stopping the German labor movement, which he made illegal by approving the Anti-Socialist Laws, while trying to attract workers with the most advanced social legislation of the moment.

In foreign policy, he was prudent in consolidating the recently won German unity: on the one hand, he forged a network of diplomatic alliances (with Austria, Russia and Italy) aimed at isolating France in anticipation of its possible revenge; on the other, it kept Germany away from the imperialist maelstrom that at that time was dragging the rest of the European powers. It was precisely this precaution against the colonial career that confronted him with the new emperor, Wilhelm II (1888-1918), in favor of prolonging the rise of Germany with the acquisition of an overseas empire, an issue that caused the fall of Bismarck in 1890. Lacking the support of Emperor Wilhelm II, who had ascended the throne in 1888, Bismarck resigned in 1890 and retired to live in the countryside.

Genealogy

Ancestry

The Bismarck family belonged to a family of the old nobility that before Otto von Bismarck had not given any relevant personality. His father, Karl Wilhelm Ferdinand von Bismarck (1771-1845), was a Junker planter and former General of the Prussian Army, who in 1806 had married Luise Wilhelmine Mencken (1789-1839), a bourgeois daughter of a high government official in Berlin. Compared to the rugged peasant hidalgo, his wife was an eminent and highly cultivated personality, whose greatest ambition lay in the training of her son. The influence exerted on the young Bismarck by the disparity of character and origin of his parents has often been discussed. In the future, Bismarck himself would feel more and more attracted to his father, despite being aware of his primitivism, his mother wanted to guide and influence him too much. The son would later state: "My mother was a beautiful woman, a lover of luxury, clear-headed and lively, but almost completely lacking in what we call Berlin character."

Offspring

Otto von Bismarck only had one wife, Johanna, with whom he had two sons and a daughter: Marie, Herbert and Wilhelm. The three of them traveled with him to the many places he visited such as Frankfurt, Saint Petersburg, and Paris. In a letter sent to his wife, he writes: "The three of them are the most beautiful thing I've ever had and that's the only reason I'm still here."

Of his three sons, the most outstanding for historians and experts on Bismarck's life was Wilhelm, as he managed to write a short biography of his father's life during his fight for the unification of Germany and in his position in the Frankfurt Parliament. However, although to a lesser extent, Herbert and Marie also stood out in German aristocratic life.

Biography

The early years (1815-1847)

Childhood

Bismarck was born on April 1, 1815, the year of Napoleon's final defeat at Waterloo. He was the third child in a large family. During his childhood, not a single outstanding event occurred. Bismarck knew himself to be a member of the nobility; his training, however, responded in essential lines to the wishes of his mother and was very different from what was then customary in the circles of the Prussian rural nobility. He studied in Berlin, first at the Plamannsche Lehranstalt, then at the Friedrich Wilhelm Gymnasium, and finally at the Grauen Kloster (“Grey Convent”).Bismarck did not stand out too much among his teachers and peers. Later it would be said that he dropped out of school a pantheist and convinced that the republic was the most rational form of government. Such words contained a retrospective critique of the educational institutions of the time, more influenced by the bourgeois spirit and humanism than by the monarchical-conservative tradition. However, affirming his involvement with the republic is, by all accounts, exaggerated.

University studies

In 1832, at the age of 17, he enrolled at the University of Göttingen to study law. Of all his teachers, Bismarck was only interested in Arnold Heeren, a historian and professor of public law, whose ideas about the European political map would largely dominate him in the future. Bismarck became a member of the Corps Hanovera student fraternity, but barely He took advantage of the intellectual possibilities offered by that university city, so famous in his time, but he gave himself body and soul to the joys of student life. Many of his adventures, of greater or lesser taste, sometimes created conflicts with the academic authorities. He himself spoke frankly and ironically of his "silent life", through which he vented a still unmoulded personality. Among his friends, in addition to members of the Corps Hanovera nobility, there were two important foreign personalities. At that time Bismarck, without any truth on his part, recognized his inner strength; In a letter addressed to a friend of his youth, he wrote: "I will be the last fool or the greatest man in Prussia."

From that time there is not the slightest hint of political opinions that give a glimpse of the future work of the creator of the Second Empire. Bismarck finished his studies in Berlin without having taken advantage of the scientific possibilities that the university offered him. In this respect, too, his vigorous nature was vented.

As far as studies are concerned, Bismarck limited himself to learning what was necessary to pass, a practice then not as common as it is today. In 1835 he took his law degree exam, which does not illustrate his ideas too much, since he responded more to the examiner's questions than to the interests of the examinee.

Work in the courts

The following years were spent in the courts of Berlin and Aachen. His final goal was diplomacy, since he ruled out dedicating himself to the other possible career for a young nobleman, that of arms. His work in the courts increased his aversion towards bureaucracy and the formalism of a rigidly regulated service, an aversion that he would retain. lifelong. Having bosses was always something superior to his strength. In Aachen he too devoted himself entirely to the pleasures of life and for months and without permission he traveled in the footsteps of a young English girl. Later he would continue his work in Potsdam.

In Aachen, his superiors recognized his ability, but felt that he needed to be more disciplined in the service. In this regard, Bismarck commented with that sincerity so characteristic of him: "I think the Aachen government has given me higher grades than I really deserve."

Retirement from bureaucratic activity

In 1838, Bismarck renounced bureaucratic activity and rigid public service. This decision matured slowly and did not meet with the approval of his parents. For Bismarck, being a civil servant and minister was not exactly luck. The official's mission —he thought— was reduced to boosting the administrative machinery ex officio, without contributing his own initiatives. "But I want to make the music, the music that I like, or I will remain silent". This rejection of the bureaucracy, otherwise widespread among the nobility, symbolizes in Bismarck a deep desire for independent activity. The statements of those years reveal a certain inclination for the tasks of a statesman. For him, the essential thing then was his desire to have a margin of action in practice. The president or minister, he said, "do not deal with people, but only with paper and ink."

Later, Bismarck dedicated himself for many years to administering his agricultural possessions, while theoretically preparing himself with studies that amaze us for their breadth. Military service, carried out reluctantly and in a very irregular manner, interrupted these activities. During this period the incessant travels and hectic life continued; his neighbors called Bismarck the 'riot'. His dedication to agriculture was supplemented by an abundant reading of historical, philosophical, and literary works. Goethe: the verse that affirms that man could, without hatred, alienate himself from the world, horrified him. He also read, sometimes without understanding them, the radical philosophers of his time: David Friedrich Strauss, Ludwig Andreas Feuerbach and Bruno Bauer. He himself spoke of his "naked theism".

In the long run, Bismarck understood that peasant life, despite traveling and reading, did not fulfill his most intimate aspirations either. He went so far as to say that his experience had made him see the illusory character of the Arcadian happiness of a fervent farmer of double-entry bookkeeping.His views of the 1940s contain severe self-criticism; in one passage he says that he "let himself be carried adrift by the river of life". von Thadden, the girlfriend of one of his friends, and a close friend of Johanna, tried to convert Bismarck, who still held very heterodox opinions on the religious issue. But it would be Marie's fatal illness that led to what has been called Bismarck's conversion, when he began to frequent Protestant and Christian circles, although without contracting a narrow religious commitment. Bismarck's essentially Protestant-Christian ideology, intimately tied to his betrothal and his wedding, cannot be abstracted from his global way of thinking as a politician and statesman; however, the description of "Christian politician" It doesn't look very tight either.

Bismarck had come into contact with Johanna von Puttkamer through her friend Marie von Thadden. In December 1846, shortly after the latter's death, Bismarck asked von Puttkamer for the hand of her daughter in a well-known letter. In it, Bismarck spoke frankly about his religious evolution, thus limiting himself to issues already known by his future father-in-law, who surely must have had some reservations about Bismarck's previous life. Bismarck, as usual, knew how to find a suitable tone and precise to please the recipient of the letter, mixing in it sincerity and diplomatic skill. The letter shows, without a doubt, in its essential features the true feelings of its author.

The marriage to Johanna took place in July 1847. Bismarck, in a letter addressed to his brothers, defined her as "a woman of intelligence and nobility of very singular sentiments". Bismarck found in she supports and helps throughout her entire existence, precisely because she carefully avoided influencing her politically in the strictest sense of the word.

The Unified Landtag (1847-1851)

Election and development as a member of the Landtag

Bismarck began his public activity a few weeks before his wedding; in May 1847 the nobility had elected him a member of the Prussian unified Landtag. The unified Landtag of 1847 was the first true parliament in German history. In it, the moderate liberals had an absolute majority. The right-wing group, which defended the authority of the crown and the interests of the latifundia nobility, had a much smaller representation. One of its members was Bismarck, who suffered, at first, the disappointment of being appointed substitute deputy.

Bismarck already had some experience in these conflicts, having previously served as Deichhauptmann (Supervisor of dikes) in the Diets. The future detractor of parliamentarism began, therefore, in political life within a constitutional and parliamentary activity. Bismarck was then aligned with the conservative forces. In his first newspaper article, Bismarck defended the right of noble landowners to practice hunting on the farms of their peasants, and also the preservation of patrimonial rights, thereby opposing both the demands of the liberals and the creed of the absolutists. Bismarck became close to Leopold von Gerlach, a close friend of Frederick William IV. Gerlach represented the Christian-constitutionalist-conservative current and rejected the authoritarianism of the State.

In his performance within the unified Landtag, Bismarck revealed himself as a die-hard rightist and a rigorous party man. As early as 1847 he was writing to his fiancée: "Man clings to to the principles while they are not put to the test, because when that happens, one discards them just like the peasant his old sandals, and runs with all the vigor that his legs allow him, which is why he has them".

Upper class defense

In principle, Bismarck defended the rights of the crown and of the nobility, something natural in him if we take into account that he was a member of the latter. Bismarck rose to fame with a crude speech in which he decidedly attacked the the thesis — not expressed, of course, with these words — that in 1813 the struggle of the Prussian people against foreign domination had had a single motive: to achieve a constitution. Such a speech caused a stormy session of the Landtag and evidenced, on the one hand, his combative and violent temperament and, on the other, his imperturbable calm in the face of any attack. When, for example, he was prohibited from speaking for some time Bismarck took a newspaper out of his pocket and began to read it. But even some of his conservative friends thought that his ideas were an erroneous simplification of the problems under discussion. All in all, the incident made Bismarck the quintessential fighter against liberalism and the constitution. Bismarck's speeches from this time show a combative and belligerent ardor, lacking objective arguments and quick to unleash his anger against circumstances. then prevailing and against the liberals.

Such an attitude became evident especially in 1848. The speeches of the years 1848-49 are accompanied by his marked warmongering and his contempt for the enemy. In these early times, that self-control that Bismarck would demonstrate in the future without abdicating his hardness was missed. In a debate on the emancipation of the Jews, Bismarck proudly acknowledged that he had received those prejudices with his mother's milk. He declared himself a supporter of the Christian State and considered the fight against the Jews - it was the general feeling of the time - basically as a confessional fight. For Bismarck, a Jew ceased to be one as soon as he converted to one of the Christian creeds. In the Erfurt Parliament he was displeased at being forced to act as secretary to a Jewish president (Simson), who during Bismarck's tenure would become the first president of the Supreme Court of Justice of the German Empire.

Follower of Prussianism

During the revolutionary year of 1848, Bismarck was a determined fighter for Prussianism and the monarchy. Appalled by the monarch's displays of weakness, he intended to lead a column of armed peasants into Berlin, and when the queen excused to her husband, claiming that he slept very little, Bismarck replied in a rude tone: "A king has to be able to sleep!"

Bismarck, deep down, was not aware that the movement of 1848 was supported by very broad sectors nor did he understand its national base. Fully identified with the Prussian-conservative ideology, he spoke of the "greed of the proletarians". He later edited a poem that the Prussian officers would sing in Potsdam on the occasion of the events of March 21. The most important verses, which undoubtedly reflected Bismarck's own sentiments, ran thus:

And then a cry broke the heart:You will not be Prussians anymore, you will be Germans [... ]

A king fell here, but not in the contest.

Finish here, Zollern, your glorious story,Fragment of a poem by Otto von Bismarck.

The king judged Bismarck's attitude in those days with the following words: "Should be used only when the bayonet stands for its respects".

After the revolution, Bismarck joined the "clique" Created by the Gerlach brothers, he was disappointed not to be elected to the Prussian National Assembly. At the beginning of 1849 he became a member of the second Chamber of the Prussian Landtag, re-elected several times, and later also a member of the Erfurt Parliament. At this time, Bismarck made his famous speech on the Treaty of Olmütz, which was the high point of his parliamentary activity. At that time he tried by all means at his disposal to defend the power of the crown and the privileges of the nobility. He participated in the founding of the Kreuzzeitung ("Diary of the Cross") and in the constituent assembly of the "Association for the defense of property and for the promotion of well-being of the popular classes", considered by the people, not without reason, as the parliament of the Junkers. The problems of domestic politics monopolized all of Bismarck's interest at that time. The German question only became important to him when the election of the emperor in Frankfurt made it a matter of Prussian politics.

Bismarck decisively and firmly directed his attacks against any liberal or democratic attempt. He thought that the opinion of the people, the basis of the movement of 1848, had been more or less directed. Each one had understood by people what was "convenient" for them, as a general rule a group of individuals addicted to their own opinion. His contempt for the people did not prevent him from attempting to manipulate or direct public opinion. Bismarck wrote to his brother asking her to send him to Berlin to make endorsements, & # 34; many endorsements from individuals, although each of them is signed by a few people, and if possible from each city; it does not matter that they are signed by a single person, because in this case they will not be made known. Blow, blacksmith, and you will earn money'. A staunch defender of the rights of the landed nobility, Bismarck judged fiscal policy as a kind of confiscation; he called the elections a lottery and strongly criticized any hint of parliamentarism; he defended Blum's execution against all odds.On the other hand, repeated statements from this time reveal that Bismarck did not hold the political talents of his peers in high regard. Prussia lacked the social class that did politics in England. Like many other nobles, Bismarck directed his attacks against absolutism and against the opinion expressed by Frederick William I: "I conceive power comme un rocher de bronze".

He believed that the revolution would come out of the civil service and the supposedly educated middle class of the big cities. He attacked the greed of the lower social strata with tireless energy and thought that constitutionalism was the most expensive formula. He fought civil marriage. All these ideas were clearly influenced by Stahl, whose theories on public law had made a deep impression on Frederick William IV.

His attitude on domestic politics also largely determined Bismarck's position on the German plans for the Frankfurt National Assembly. He did not fight it, as has often been claimed, because he rejected his views on domestic politics. Bismarck, a man of Prussian and conservative ideology, did not at all want the German question to be resolved at that time. In the lowest days of Prussian power there are certain manifestations of Bismarck in which echoes of a national policy resonate. But these appraisals will disappear when the subsequent evolution allows Bismarck to put his hopes in Prussia again. Bismarck exclusively sought to place Prussia on a par with the great powers, while in domestic policy he devoted all his energies to combating the revolution. In his opinion, the Paulskirche's plans were directed against Prussia, attempting to undermine its position and its political base.

Real interest in the German question will awaken when the election of the emperor in Frankfurt causes differences in Berlin. At that time, Bismarck, in opposition to the "German hoax", used to refer over and over again to his pure Prussianism. & # 34; We are Prussians, and we want to remain Prussians! & # 34;, he exclaimed on one occasion. Nor did Bismarck judge the fate of Schleswig and Holstein from a nationalist perspective, which aroused such deep concerns in political circles. For him, the struggle of the inhabitants of Schleswig and Holstein meant an uprising against his rightful lord, the King of Denmark.

Bismarck was strongly opposed to the King of Prussia accepting his election as emperor, decided by the National Assembly in Frankfurt. He also distrusted official institutions, which had been impressed by the Paulskirche's rigging. In April 1849 he was of the opinion that Prussia should remain Prussia, since it would thus be in a position to give laws to Germany, giving his words a new tone and accent: "If you ask anyone who speaks German for unity German, she will reply that she wants it; but to me, with this constitution, it does not seem desirable at all'. In reality, Bismarck only wanted harmony and concord to reign among the different German states and flatly rejected any unifying policy that limited power and freedom. Prussian autonomy.

This is demonstrated with particular clarity by Bismarck's opposition to the unification policy that carried out the failed attempt to achieve, thanks to the Prussian government, the objectives in which the National Assembly in Frankfurt had failed. Bismarck fought the leader of said unifying tendency (Joseph von Radowitz) with all the means at his disposal and made him the target of his ridicule. Bismarck, who advocated Prussian nationalism as a specific factor, feared that the Prussian monarchy would disappear in the "stinking revolutionary upheaval that was throwing southern Germany into chaos." German soldier Was ist des Deutschen Vaterland? ("What is of the German homeland?"). And when a liberal deputy described him as the prodigal son of Germany, Bismarck He replied: "My father's home is Prussia, and I have neither abandoned it nor will I ever abandon it." thus the question from the perspective of the individuality of Prussia and warmongering in domestic policy, suppose the harshest criticism of the German aspirations of his time. At that time Bismarck was not yet aware that the Prussian policy was as unrealistic as the of the liberals. He wanted to establish an intimate union with Russia, animated - like the Gerlachs - in his heart of hearts by the conviction of the conservative solidarity of the great monarchies.

To tell the truth, as early as 1849 there are a series of signs that reveal Bismarck's overcoming of his rigid ties to domestic politics. In a letter addressed to his wife, he stated that the German question would be resolved through diplomacy or arms; in one of his speeches, he opined that Frederick II the Great had not promoted political unification, but "the trait highlight of Prussian nationalism: militarism".

He knew that today, as in the days of our fathers, the sound of the trumpet, inviting the Prussians to enlist in the armies of their sovereign, retains all its attractions for the ears of the people of Prussia, since it is about defending one's own borders or seeking glory and the greatness of Prussia.

Frederick, having broken with Frankfurt, could have chosen to join his former ally, Austria, and thus assume the brilliant role played by the Emperor of Russia, that is, to annihilate, in alliance with Austria, the common enemy, the revolution. He too could have, with the same right that he occupied Silesia, imposed on the Germans, after refusing the imperial crown offered to him in Frankfurt, a certain constitution, even at the risk of unbalancing the balance with his sword. This would have been a Prussian national policy, which would have given Prussia (in the first case in collaboration with Austria, and in the second by itself) the rank necessary to give Germany the authority she deserves in Europe. These words undoubtedly preluded the political approach to problems that would prevail later in the fifties. In the same speech he went so far as to affirm that the & # 34; Prussian eagle & # 34; he was to spread his "protective wings and dominate the space from the lower Niemen to the Donnersberge". These words constitute the first indication that Bismarck aspired to Prussian hegemony in northern Germany. But on the whole, Bismarck's position did not differ sharply from that held by his closest friends (Leopold von Gerlach in particular).: they did not want to restrict themselves exclusively to the great Prussian king and strove to avoid a fight with Austria in the interest of the common domestic policy objectives of both powers.

In this regard, Bismarck defended, on December 3, 1850, the preliminary treaty of Olmütz (signed the previous month), by which Prussia renounced its policy of unification and reached an agreement with Austria, ceding to pressure from Russia. The event was a serious defeat for Prussian politics. Despite everything, Bismarck defended the agreement with skill and brilliance in the famous speech delivered before the second Chamber, from which it can perhaps be deduced that he was not fully aware that, from an imperialist perspective, such an event meant a defeat for the State. Prussian. He would later justify himself by arguing that at that time the Prussian army was not in a position to face a war. However, the real reason for Bismarck's attitude was quite another: at that time he was absorbed and influenced by translating solidarity into domestic politics against "black, red and gold democracy", and he devoted all his efforts to keep the peace. Radowitz's dismissal filled him with jubilation. In the letters he wrote to his wife, he compared the German hoax and the anger towards Austria. He believed that peace was also in the interest of "our party". Conservative armies were not to annihilate each other; according to him, it was not honorable to "condemn the path of revolution with words and yet follow it in practice". Prussia and Austria, on an equal footing, were to reconcile with each other at the expense of smaller states.

Despite the powerful ties that domestic policy imposed on his conception of foreign policy, the speech contains divergent formulations with the foreign policy theories of his conservative friends:

The only healthy basis of a great state—which marks other essential differences with the smaller states—is state selfishness and not romanticism; it is therefore not worthy of a powerful state to fight for a cause other than its own interests.

It's all too easy for a statesman to call for war, make fiery speeches, and trust the musketeer, who bleeds out in the snow, with victory and glory for his system or not. Yes, nothing is easier for the statesman, but woe to him who in these times cannot find plausible reasons to start a war". Bismarck was opposed to the classification of Austria as a foreign country, and in fact called his heir monarch of a long series of German emperors.

Strange modesty that forces us not to consider Austria a German power. The only reason I can think of is that Austria is lucky enough to dominate foreign areas that were previously subjected to by German weapons.

This statement by Bismarck has been interpreted, erroneously, in a pan-German sense; however, his conception was in clear opposition to the then prevailing situation: Austria was a State whose fundamental feature was not being inhabited by a German population, but rather his character as a great power that he had often and successfully wielded the German sword.

This series of ideas, however, still remained encompassed within the thorny question of internal politics. The Prussian honor passed by refusing any type of union against nature with democracy. Austria and Prussia were the two protective powers, with equal rights, of Germany. Bismarck still believed at that time in the true equality of the two powers and was prepared to achieve it de facto at the expense of the smaller German states.When he was appointed ambassador to the Frankfurt Parliament soon after, he went there considering himself Austrian friend. Already in 1849 he had leased the family estate from him and had already moved to Berlin. Thus, by the stormy revolutionary era, Bismarck had renounced his profession as a peasant hidalgo.

Ambassador in Frankfurt, Saint Petersburg and Paris (1851-1862)

Bundestag in Frankfurt

In 1851 Bismarck became ambassador to the Diet of Frankfurt; at that time it was the most important position in Prussian diplomacy, and Bismarck himself recognized it as such. The appointment of a person lacking preparation in the diplomatic field to occupy such a position was an extraordinary event. The proposal had come from Leopold von Gerlach, who saw in Bismarck the eternal counterrevolutionary fighter allied with Austria. Bismarck went to Frankfurt, according to his own words, in a state of & # 34; political virginity & # 34;.

During the first moments, his ideas on internal politics remained unchanged with respect to those he had maintained in the time of 1848. Until 1852 he continued to belong to the second Prussian Chamber, and in it he developed a radical and very personal struggle. That same year a political discussion with the prominent liberal Von Vincke even led to a duel without consequences. As in the past, Bismarck declared himself a supporter of the Junkers and criticized the constitutional system; What's more: on one occasion he even said that the Prussian people would make the big cities return to the fold of obedience, "even if to do so they had to wipe them off the map". These words earned him the adjective & "Annihilator of cities". On the other hand, he incessantly condemned absolutism, equating it with the liberal bureaucracy. Upon receiving his ambassadorial appointment in Frankfurt, Bismarck went so far as to mock himself, stating, "My becoming a Privy Councilor is an irony with which God punishes me for having spoken ill of Privy Councillors."

Upon his arrival in Frankfurt, Bismarck believed in equal rights between Austria and Prussia. Since the days of the Hohenstaufen he had never enjoyed such prestige in Germany. But this trial would not take long to change, as a result of attending the Bundestag sessions: in it the discussions turned on trivial issues, and Bismarck spoke of the charlatanism and presumption of its highly intelligent members, who reduced everything to borage water; he criticized the social life of Frankfurt, the excessive fondness of diplomats for dancing and the bourgeois features of the society of that city. Bismarck was forced to dance the rigodon with the wives of his suppliers, but at least "the kindness of such ladies made me forget the bitterness at the exorbitant bills and bad goods that their husbands provided me". the typical pride of the Junker in front of the bourgeois society of an old imperial city devoid of courtly nobility. Despite everything, at first Bismarck felt very comfortable, to the point of confessing to Gerlach in a letter that "in Frankfurt he lived like God".

The fundamental problem for the new ambassador was the attitude to adopt towards Austria, largely the result of Prussia's representative to the Bundestag. Before 1848, Austria had avoided defeating the second party by force of votes great German power, despite the fact that during the Metternich era the superiority of Austria was, in this field, indisputable. At the beginning of his stay in Frankfurt am Main, Bismarck had visited the former chancellor Metternich at his palace in Johannisberg, and it seems that the two statesmen got along wonderfully. Metternich also criticized the attitude of his successor, Schwarzenberg, who stressed Austrian supremacy. From 1848, after the election of the emperor, Austrian politicians saw Prussia as a rival and wanted to relegate it to the background. Bismarck soon raised his voice against the inconsiderate rule of the majority, which would ultimately ruin the Confederacy. He realized that, contrary to his own ideas, Austria had no intention of recognizing Prussia's equal rights, so Bismarck's first goal in Frankfurt was to fight for equality, using all means at his disposal. Following this behavior, the Russian ambassador compared Bismarck's performance with that of the students. To his colleagues, the rudeness of the young Prussian ambassador's methods evidenced a lack of genuine diplomatic education. Bismarck pleaded for equality before the Austrian minister plenipotentiary Count of Thun, sometimes employing visibly drastic means.

Basically, the motor of Bismarck's activity in the Bundestag was the fight for equality and not the preparation of the ground to settle the hegemony in Germany. By the end of November, the differences between von Thun and Bismarck had deepened, and the latter reported to Berlin:

Thun spoke and spoke, leaving behind his pan-German fanaticism; I argued that the existence of Prussia, and more after the reform, was a factum certainly annoying, but also unmodifying; I argued that we had to depart from facts and not ideals, and I begged him to meditate if the results that Prussia was going to achieve on tortuous paths could compensate the advantages of the Prussian alliance; for a Prussia that — with its own words — "renunciated to the heritage of Frederick the Great," would have to give itself full to its true providential destiny of chambel.

Thun compared Prussia to a man who had won first prize in the lottery and wanted the event to be repeated every year. Bismarck replied that if Vienna thought so, Prussia would have to play the lottery again. This was the first time that Bismarck considered the possibility of a confrontation with Austria, despite being aware that, under Frederick William IV, such a policy was crazy. Perhaps what bothered him most about Thun's words was realizing that they hid, deep down, a great truth. In later years he would sometimes apply Goethe's quote to Prussia: "We have come down without hardly realizing it."

At that time, Bismarck neither wanted nor contributed to the break with Austria. The position of said nation was due, according to him, to its own internal situation. However, he soon realized that the federation was simply a brake on Prussian policy and he therefore began to recommend a policy of independence. In a letter to his sister he wrote that Heine's famous lied:

O Bund, du Hund, du bist nicht gesund!Ow! Confederation, bitch, you're sick!

Soon it would become by unanimous decision of the Germans the national anthem. Bismarck thought that Prussian demands had to be satisfied by individual pacts "within the geographical area that nature has destined for us". He informed Gerlach of the differences with Austria, "thanks to which later or sooner the Confederation chariot will sink, in which the Prussian horse pulls forward while the Austrian pulls back". In this sense, Bismarck acted with absolute consistency: when negotiating the rights of the press, achieved that the attacks on the stability of the Federation were not prosecuted. With marked irony, he went so far as to affirm that the free press was enthusiastic about these circumstances. Bismarck was harshly critical of the political egoism of German states that pursued a German policy, actually seeking their own interest. Later, as Chancellor of the Empire, he would behave in a similar way, speaking of Europe's abuse of the word of Europe by the great powers. Bismarck was always an open supporter of defending the interests of the State itself, but it is also true that he assumed the same attitude in others.

During his stay in Frankfurt, Bismarck displayed a frenetic reporting activity, ranging from official writings to private appointments. Surely he would not have been an easy opponent for the Austrians, and from their reports it is known that his statements did not always coincide in tone with the information that, as ambassador, he sent to his superiors. Bismarck's position was very sincere and truthful, but already then he puzzled his interlocutors precisely because of his expressive frankness. The British statesman Disraeli once warned: "Beware of that man, because he wants to put what he says into some practice." Bismarck himself once complained about how difficult it was to convince the Austrians of the falsehood of the theory (based on already obsolete traditions) of lying as an inherent factor in diplomacy.

During his time in Frankfurt, Bismarck knew that his marked "Prussianism" he would not find any echo in Federico Guillermo IV, nor that he would be a minister during his reign. Later he would say that said monarch had demanded blind obedience from him: "He saw in me an egg that he himself had laid and that he hatched, so that when it came to differences, he always thought that the egg wanted to be smarter than the other." the hen".

In another passage he writes: "Alas! I wish one could act according to one's free will! However, here I am wasting my strength under the orders of a gentleman who can only be obeyed by resorting to religion". This state of mind is also explained by the concerns that Prussian policy aroused in Bismarck during the Crimean War Bismarck strongly advocated that his country take no action against Russia:

It would give me a deep concern that, in the face of the possible storm, we seek protection by sheltering our beautiful sailor from the old and carved skiff from Austria. We are better swimmers than they and also a much desirable ally for anyone.

Great crises generated the storm that drove the rise of Prussia.

During the Crimean War, the representatives of the central states in the Bundestag agreed with Bismarck's policy of not allowing himself to be drawn into a conflict by Austria. In any case, in Bismarck this perspective coincided with his desire to disassociate himself from Russia and Austria, which before the Crimean War undermined Prussia's position. Bismarck expected a sharpening of the opposition between Austria and Russia, a fact that was a prerequisite for Bismarck to achieve political successes in the creation phase of the Empire, since during the Crimean War he worked with all his might so that Prussia would not be face off with Russia.

Within this context, Bismarck never tired of attacking the soft political romanticism of Frederick William IV, while accentuating his opposition to the Austrian rulers of his time. When, at the end of the Crimean conflict, Prussia was not Invited to the Paris Conference, Bismarck flew into a rage and compared her state of mind to that of the spring of 1848. Shortly thereafter, she warned in a comprehensive report that Austria was the only country against which Prussia might suffer defeat or defeat. lasting victory.

Actually, Bismarck did not want to provoke any war at that time, especially because he knew that this was impossible under Frederick William IV. However, he was fully aware that one day this fight generated by the problems of German dualism would have to be faced, and for this reason Bismarck's words do not speak of the disappearance of the regulation of German dualism, contrary to other erroneous interpretations. In a letter addressed to his friend Gerlach, Bismarck demands a delimitation of the spheres of influence in Germany with a geographical or political demarcation line. Thus at least a war like the Seven Years' War would clarify relations between Prussia and Austria.

Friendly Austria had become the stalwart Habsburg enemy, so hope was being lost that the situation would change with a different internal Austrian policy. Prussia would always remain powerful enough to allow Austria the freedom of movement that she covets. Our politics has no other field of maneuver than Germany[...] We take the air we breathe out of each other's mouths, one has to go back, either voluntarily or forced by another". Anyway, these words do not mean that Bismarck ventured down the path that he would start later, in 1866. The expression of millennial dualism, vague and imprecise and going back too far in time, emanates from the contrast between northern and southern Germany. between Protestant and Catholic. Bismarck did not intend to eliminate dualism, but to set the clock of progress. In this regard, Bismarck was aware that northern Germany was a zone of Prussian influence. This nation was not yet fixed, and a simple glance at the map showed it. In this situation, Bismarck even thought of establishing political contacts with the France of Napoleon III. Other powers believed that Prussia and France could never converge, and this weakened Prussia's position. Bismarck visited Paris twice from Frankfurt to meet with Napoleon, and he had the impression—correctly so—that the great Napoleon's nephew was more bland and banal than the world supposed.

Bismarck's contacts with Napoleon led to a famous dispute with Gerlach over political guidelines determined by the internal situation. For Gerlach, Napoleon represented the revolutionary ferment and consequently any type of negotiation with him was a diabolical action. Unlike his friend Bismarck, Gerlach thought that convictions on domestic policy lacked relevance in the field of foreign policy. From France he was only interested in his reaction to Prussia.

As far as foreign people and powers are concerned, I cannot justify sympathy or antipathies, nor do I admit that of others, because I am not allowed the sense of duty in the foreign service of my country. Hence, the embryo of infidelity begins to the Lord or the country to which it is served.Gerlach

Gerlach thus defended himself against the Bonapartist accusation. He was a Prussian and in foreign policy his ideal was based on an absolute lack of prejudice, on independence when it came to judging the aversion or predilection for foreign States. Napoleon was not the exclusive representative of the revolution, since individuals arose everywhere who firmly sank their roots into the revolutionary substratum.

Many of the conceptions that you mention in your letter are already perpetuated, and yet we have become accustomed to them; the fact must not marvel at us, just as we do not marvel at that series of wonders during the four and four hours of the day; we must therefore prevent the application of the concept of "prodigy" to phenomena that in themselves are no more amazing than the birth and daily life of man.Bismarck

With this argument, Bismarck breaks with the fundamentally deterministic ideology of his friend Gerlach and, therefore, with that of the Prussian monarch: "We must govern by sticking to reality and not fiction". During his course, Bismarck did not abjure his conception of the monarchical-conservative and Protestant world, although he flatly refused to base a very limited foreign policy on it on a theoretical level. His ideas on foreign policy underwent an evolution — not always taken into account—which was already prevailing throughout Europe at that time. Even Russia abandoned the principled policy that had led to its alliance with Austria.

Bismarck did not harbor, at any time during the dispute, the intention of breaking with Gerlach, and in fact in one of his letters he confessed that he was willing to compromise and repair the injustice, if he showed him that his position was wrong Gerlach was of the opinion, however, that his opponent's outspokenness was pure rhetoric; Bismarck's behavior in Frankfurt and his advice to Berlin became increasingly forceful, and he came to adamantly reject a tacit convergence with Austria. A representative of the latter power described one of his conversations with Bismarck with the adjectives & # 34; miserable and barely credible & # 34;. The Count of Rechberg, Bismarck's Austrian interlocutor, stated in 1862:

If Mr. Bismarck were dubious in diplomatic lydes, he would be one of the great statesmen of Germany, if not the first; he is courageous, firm, ambitious, dense, but incapable of sacrificing his preconceived ideas, his prejudices or his partying ideas to any principle of superior order; he lacks fully a practical political mentality. He's a party man in the strictest sense of the word.

Rechberg was no longer shy about saying that Bismarck did not seem willing to submit to the superior dictates of conservative government policy: Prokesch, another of Bismarck's opponents, would reaffirm this more forcefully later in Frankfurt. Prokesch, therefore, perceived with crystal clarity the Prussian essence, the Prussianism underlying Bismarck's attitude, something that the latter never denied; He also harshly criticized the mutual deception of people thanks to the "systematized lie"; which empowered anyone to talk about sacrificing for Germany instead of acknowledging self-interest.

At the end of the Crimean War, Austria was left largely isolated abroad. The Holy Alliance —and this was confirmed by Bismarck with an air of satisfaction— had died. In any case, two events restricted Prussia's freedom of action: the illness of King Frederick William IV and the non-establishment of the regency until 1858, which would provide the future King William the freedom of political action. The new orientation, initially cherished by the Prince Regent, reduced Bismarck's support in Berlin. The Regent spoke of the future Chancellor with little sympathy, and his wife Augusta had hated him since 1848. The program of Prussia's moral conquests in Germany was in frank opposition to the tone used by Bismarck in Frankfurt. In spite of everything, the latter tried to exert a constant influence in Berlin to achieve his political objectives, and among other things he insisted that Prussia, if it showed a liberal attitude, could set goals so wide that Austria would be unable to accept; however, he would be very careful not to provoke Prussia with liberalizing propaganda methods in order to win the national sympathies of Germany. Prussia would not take great effort to neutralize Austria in this area.

At the end of March 1858, Bismarck presented Prince William with a lengthy memorandum known as Mr. Bismarck's Little Book, which could not have impressed the Regent too much, in the unlikely event that it ever reached him. to read his lengthy arguments. The memorandum revealed with particular clarity Bismarck's expressive conciseness, his aptitude for apt metaphors and comparisons, and his refined style.For Bismarck, the identification between the Bundestag and Germany was a pure fiction:

Prussia's interests are entirely consistent with those of most countries belonging to the Confederation, except Austria, and not with those of the governments of those countries, and nothing more German than the development of the particular interests of Prussia well understood.

He demanded independence from Prussian politics and ventured the idea of using liberal institutions in favor of Prussia and against Austria and the Confederation. In March 1859 he stated, in the course of a conversation, that the German people were the Prussia's best ally; Bismarck wanted to negotiate with the German states outside the Confederation, just as he once did with the German Customs Union. people knew, the greenhouse plants of Confederate politics; He even stated that even on the question of Schleswig-Holstein it would be possible to adopt an attitude more in keeping with the national idiosyncrasy.

Since the regent sought a policy of good relations with Austria, such suggestions fell on deaf ears in Berlin. Bismarck's position in Berlin had weakened since the formation of the new age cabinet. His behavior in Frankfurt had earned him the hatred of Austrian politicians and the central states. His tactic clashed head-on with the attempt to effect moral conquests in Germany. At that time, Bismarck enjoyed practically no sympathy among the representatives of the other German states. In the end, the influence of Austrian diplomacy achieved the transfer of the uncomfortable ambassador to the Bundestag, a fact that Bismarck judged a defeat for his own policy. Despite the fact that he was appointed ambassador in Saint Petersburg, considered the most important position in Prussian diplomacy, Bismarck did not mention that they wanted to silence him along the Neva. Quite rightly, as a victory for Austrian policy, for it took him away from his real task. At the farewell session of the Frankfurt Diet, Bismarck renounced the usual phraseological remarks characteristic of such occasions, thus preventing the Austrian presidential ambassador from delivering his planned farewell address to Bismarck.

During his last days in Frankfurt, the latter met often with the Italian ambassador, a fact that caused great concern about the war that was coming between Austria, on the one hand, and France and Italy, on the other. other. In May 1859, Bismarck wrote to the regent's aide-de-camp:

Given the current situation, we have once again the first prize, if we let Austria and France wear themselves in the war and then head south with all our troops, we start the border posts and nail them back to Lake Constance or in the area where the predominance of Protestantism ceases.

According to him, the inhabitants of such territories would willingly side with Prussia rather than in favor of their previous governments, especially if the regent changed the name of the Kingdom of Prussia to the Kingdom of Germany. In this aspect, Bismarck underestimated the antagonistic forces of the Protestant territories and limited the plan to move the borders while respecting the Catholic south.If Bavaria turned out to be too big a fish for that hook, he could let it get out of it. In summary: at that time, Bismarck, like Ferdinand Lassalle, wanted to take advantage of the war between France and Austria as a throwing weapon against the power of the Habsburgs. that Prussia undertook an expansionist policy. Despite everything, Bismarck, had he directed the foreign courses of his country, would hardly have followed the policy set forth in that private letter. On the other hand, the letter unambiguously reveals his final goal, Pan-Prussian and Protestant. Bismarck did not at all aspire to fix the borders of a reduced German state. Even in 1866, the limitation of Prussian expansionism to northern Germany and the area of Protestant dominance was to play a major role. Despite everything, the letter faithfully reflects the evolution of Bismarck, who went from being an ally of Austria to his most bitter opponent and at the same time showing that he had overcome any rigid and closed-in expansionist policy. against Russia, it no longer deserved credit in the interior. However, on the political level, Bismarck's personal evolution would be enriched by new experiences outside the reduced setting of Frankfurt am Main and would be a direct consequence of his appointment as Prussian ambassador to the court of Saint Petersburg.

Ambassador in Saint Petersburg

Bismarck arrived in Saint Petersburg at the end of March 1859. The city initially made a very pleasant impression on him: "The only thing that drives me crazy is not being able to smoke on the street". In Saint Petersburg, Bismarck was welcomed by the royal family with open arms. A long illness interrupted his activities. He also remained outside that city, specifically in Berlin, for almost a year awaiting his appointment as minister.

During the first months in Saint Petersburg, Bismarck, as he had done during the Crimean War, focused all his efforts on preventing a Prussian intervention in favor of Austria, aware that Russia would not tolerate it. Prussia, he thought, was not rich enough to exhaust its resources in wars "that do not benefit us at all". He also spoke of the possibility of taking advantage of the situation created to break away from the Confederation:

In my understanding, Prussia's relations with the Confederation constitute a scourge for our country, that sooner or later we will have to cure ferro et igniif we don't take advantage of the station to undertake the right treatment.

Bismarck preached the removal of the Bundestag, dominated by Austria and the central states, but on the other hand he accepted his country's foreign policy with resignation:

We will continue to be a drifting board springing our own waters, pushed from one side to the other by foreign winds, and what winds!: petty and fed.

At that time, Bismarck defended himself against the continuous attacks directed at him by the press, reproaching him for his petty conception of foreign policy. To him, however, it seemed honorable to be feared by the enemies of Prussia and he rejected the reproach they made him of wanting to hand over the left bank of the Rhine to the French. In a final polemic with Leopold von Gerlach, Bismarck justified his judgment about Napoleon III, arguing that too much importance should not be attached to him. For him, Prussian policy had to meet criteria of political pragmatism. It is true that he did not want an alliance with France, but that possibility should not be ruled out either, "because you cannot play chess when you have been prohibited from doing so. beforehand 16 of the 64 boxes". He believed the creation of an Italian state useful for Prussian politics, thus supporting an opinion antagonistic to that of his conservative friends. In December 1860 he wrote to the minister:

With regard to the internal politics of my country, I am, by conviction and pragmatism, amen by custom, as conservative as my monarch and owner and lord allow me, and I would be able to go to the Vendée even by a king with whose policy I disagreed; but only by my king. However, with regard to relations with other countries, I do not recognize any commitment based on principles; I contemplate its policy only in the light of its usefulness to my country.

In September 1861, Bismarck criticized the negativist vision offered by the political program of the Conservative Party, since he limited himself to saying that it was not what he did not want. In his opinion, the idea of solidarity between conservative interests was a dangerous fiction; he attacked the & # 34; hoax of sovereignty & # 34; of the German princes and defended certain common institutions. "Furthermore, I don't understand why we recoil like weasels at the idea of popular representation, either within the Confederation or in a Customs Union Parliament& #34;. With this idea of popular representation, Bismarck intended to frighten the governments of the other German states and at the same time converge with that powerful current of the time that fostered nationalist sentiments. He was the first to express the idea of unifying Germany, excluding Austria, and outlined an attempt to solve the problem with the help of a National Assembly. Bismarck therefore thought that Prussia could negotiate with the other states apart from and even against them. wishes of the Frankfurt Diet.

While at the time of the revolution Bismarck emphasized his accentuated Prussianism, now, in his formulations, the interests of Germany and Prussia are identified. Already in the summer of 1860 he affirmed:

The case is that in the long run we have only a safe point of support [...] the nationalist vigor of the German people, and so it will be as long as it considers the Prussian army its champion and its hope for the future and does not see that we go into war to favor other dynasties than those of the Hohenzollern.

In March 1861, he stated that the Habsburg Monarchy should shift its center of gravity to Hungary.

All these projects and political insinuations arose at a historical moment in which Prussia had increasing difficulties at home. The constitutional conflict ignited with the question of the reform of the army, of which the regent had made a personal matter. Von Roon, Minister of War and anti-liberals in the new era, defended Bismarck's appointment as minister. The Regent, however, was reluctant to take that step, being suspicious of Bismarck: "He considered me more fan of what he really was". By then, Bismarck, despite his conservative ideology, had proposed, for the sake of German politics, not to sharpen the opposition to the liberals and had his doubts about the appropriateness of the king's desire to receive the oath of allegiance in Königsberg, idea that horrified liberals. Bismarck thought that the crown could only avoid internal conflicts by fostering an evolution in foreign policy.

The lack of political experience has contributed powerfully to the current trend of looking at the most chemo issues: for fourteen years we have instilled in the nation the taste for politics, but we have not satisfied its appetite and are now looking for food in sewers. We are almost as frivolous as the French; we are convinced of our prestige abroad and yet we tolerate many things inside.

Bismarck strongly advocated a more independent foreign policy with each day of dynastic sympathies. House opposition to military reform would disappear at a stroke if the monarch hinted that he would use the military to support the policy of national unification. This analysis very accurately captured the attitude of the Diet; on the other hand, Bismarck wanted to act forcefully against the opposition deputies.In a letter to Roon he predicted that his appointment would soon show that the king was far from giving up:

Perhaps then, in passing the minister's magazine to a battalion prepared for the struggle, it produces an impression that is unthinkable at the present time; it is more: if you first give the matrac with noise of sables and rumors of coups, my old brutal reputation of irreflexive will help me and everyone will think: "Caramba, already has begun the saurus". Then there is no doubt that the rest of the States will come to negotiate.

In March 1862, Bismarck was ordered to leave St. Petersburg. However, King William was not yet fully decided to appoint him a minister.

Ambassador in Paris

In April 1862 he moved to Paris as Prussian ambassador and stayed there until September of that same year. These months were more of a vacation, as Bismarck did not have much work. Taking advantage of his visit to the International Exhibition of London, he came into contact with prominent personalities in English life. When he went to the French capital, Bismarck left alone, deducing from an observation by his king that his ministerial appointment was about to fall. Driven by his impatience, he wrote letter after letter to his homeland, especially to Roon, urging him to make the decision he hoped for. To his wife, however, who did not want to be appointed minister at all, he confided that, if he came to the position, he would last in it for a few months. In those years, Bismarck did not aspire to be a minister and in fact insisted on several occasions when he preferred the embassy, since it seemed like a paradise compared to the maddening ministerial work: "However, if they point a gun at me asking me to answer yes or no, I would feel cowardly if in the current situation, so intricate and difficult, he answered with a "no". In Paris, the provisional nature of the situation made him uneasy. He wanted to take responsibility for him, but he was also aware of the difficulties involved in his task and had decided that he would only accept the position of minister-president with the king's unconditional support.

Since his stay in Saint Petersburg, his state of health caused him serious concerns. In the days of Frankfurt he complained that his existence was spent between the office and the receptions. "I am often overcome by a feeling of deep nostalgia when after finishing official work, I ride, lonely, through the forest and remember the bucolic tranquility of my past life". Despite everything, in Frankfurt, his health did not suffer. His work in the Bundestag left him plenty of time for horseback riding and swimming.In 1859, however, he contracted a serious illness; for a long time he suffered the consequences of it, lamenting that he did not fully recover. At the beginning of 1862 - the year in which he was appointed minister-president - he said: & # 34; Three years ago I would have been an acceptable minister, but today I see myself as a sick riding artist and forced to continue with his jumps & # 3. 4;.

Bismarck then explained that he had a reverential fear of meddling in the negotiations about his future. It was something very typical of him: he was divided inside and always played with various possibilities in order to both his personal and political destiny. Bismarck always maintained the opinion that not even a great statesman could shape history. He judged his own actions and the situation of his country with resignation. In November 1858 he entertained the idea of retiring to the "guns of Schönhausen" #34;, that is, to renounce political activity. In the times of the new era, the situation in his homeland made him desperate:

But God, who can preserve and annihilate Prussia and the world, knows why things have to be so, so that we do not wish to exasperate with the country that has seen us born or with its government, for whose enlightenment we pray [...] Be what God wants, for all is a matter of time, peoples and men, foolishness and wisdom, peace and war, which go and come like waves while the sea remains. In the eyes of God, what are the nations and their power and their glory, but antlers and hives that crush the hoof of an ox or reach the skill disguised as a pin?

Despite his eagerness to serve his country, Bismarck, impressed only by the salvage medal among many decorations, lacked any outward ambition or vanity. He was always of the opinion that the individual could not forge destiny: "We can only wait until we hear the echoes of God passing through events, and then rush forward to seize the tip of his tunic".

Within the global analysis of Bismarck, one must also consider his close connection with nature, his love for plants and his joy in any beautiful landscape. The infinity of landscape descriptions that populate his correspondence demonstrate his extraordinary expressive power. Bismarck's reports reveal his author as one of the best German-language prose writers of the 19th century. He was also a good family man, loving and understanding with their children; He always tried to comfort her wife because of the official obligations inherent to her position, which for her, surely, must not have been pleasant at all. Johanna very reluctantly awaited the possibility of her husband becoming a minister. In fact, Bismarck told his wife of his appointment when she must already have known: "You must have heard of our misfortune in the newspapers";. On the other hand, weeks before Bismarck had agreed with Roon a key so that the former would return to Berlin when the decisive hour arrived. However, a vacation trip to Biarritz made him forget politics completely. He spent some unforgettable days in the town in the company of the Russian diplomat Prince Orlov and his young wife. In a letter to his sister, Bismarck acknowledged having fallen a little in love with the "pretty princess": "You know what this happens to me sometimes, without harming Johanna". He wrote to his wife saying that the holidays had finally restored him completely. As in the past he had done in Aachen, Bismarck prolonged Motu proprio his permission and forgot about the mail and the press. Upon returning to Paris, he found a telegram from Roon with the agreed code:

Periculum in mora, dépêchez-vous.The delay is dangerous, hurry up.

Reasons for appointment as minister

Given the direction the constitutional conflict had taken, the king found himself in a bind. Had there been another solution, Guillermo I had not named Bismarck minister-president. Subsequent historical reflections have often made us forget that at the time of the appointment everything seemed to indicate that the power of the Prussian crown, far from ascending, declined. Since the death of Frederick the Great, no great king had sat on the Prussian throne. The sympathy emanating from the simple personality of William I should not have hidden the fact that as regent and as monarch he had led Prussia to a blind alley. He wanted to abdicate, since the ideology of his ministers did not allow him to continue the policy that seemed prescribe your conscience. If Frederick, the crown prince who acceded to the imperial throne mortally wounded, had seized the opportunity then, Bismarck would not have been appointed minister and Prussian and German history would have been very different. The crown prince's refusal in September 1862 to accept the His father's projected abdication was due primarily to humanitarian considerations, although perhaps he was also influenced by a sense of having to face an irresolvable task.

The monarch's abdication plan generated, for Bismarck, a new situation. Abdication, at least initially, would have meant a victory for the Liberals, something Bismarck and his friend Roon were determined to avoid at all costs.When they arrived in Berlin, his appointment was far from decided. In an interview held at Babelsberg castle between William and Bismarck, the king discussed the desperate situation in detail with his interlocutor, and in the end he ended up convinced and in agreement with Bismarck that strong measures had to be taken against the Chamber of Deputies. appointed minister-president because there was no other option. Bismarck promised to implement the military reform even with the opposition of the majority of the Chamber of Deputies. In the course of the interview, Bismarck solemnly promised the monarch absolute and unconditional fidelity, rendering him vassalage almost as in past times, but at the same time he suggested the destruction of the draft program that he had formulated in writing.

Appointment as minister

On September 23, 1862, Bismarck was appointed Acting Minister-President of the Council of Ministers; the final and firm appointment took place on October 8. The King profusely apologized to his wife for having appointed to the charge to his deadly enemy: "After careful prayer and consideration of the matter, I have at last come to that decision," he wrote to Queen Augusta.

In those days, no one was capable of even remotely imagining that such an appointment would initiate a collaboration of almost three decades between the monarch and his new minister-president. Nor could it be assumed that this man, whom the people labeled Junker for his behavior during the year 1848, would achieve the unification of Germany in a relatively short time. At first, the general impression was that the Bismarck's cabinet would not last long, and he himself believed so based on the previously mentioned letter that he wrote to his wife. Everyone feared a government outside of state institutions, a predominance of sabers, wars abroad and a ruinous decadence following in the footsteps of the elderly Heinrich von Treitschke, who wrote at the time that "it was governed showing signs of consummate frivolity". To this must be added the opposition to the foreign policy of his friends conservatives and even the king. The success of the thorny question of Schleswig and Holstein in 1864 seemed to convince most that the Bismarck cabinet was far from a mere episode. In any case, foreign diplomats were quick to realize that the then Prussian ambassador in Frankfurt am Main was a man of great political gifts.

The constitutional conflict (1862-1864)

Possession of the n#34;Prussian helm#34;

Bismarck took the helm of Prussia at a very challenging time, both internally and externally. Nothing could be further from his spirit than to sharpen the disputes around the constitutional conflict, and he stressed this over and over again in the first weeks of his term; He used kind words with the deputies, and as a symbol of reconciliation he presented the olive branch that Katharina Orlov had given him when they said goodbye in Avignon. His gesture did not find any echo, since everyone believed that he was in favor of a policy based on violence. His words, which offered the possibility of reaching an agreement, barely managed to impress the deputies, since the two parties started from radically different ideological approaches. Nobody believed that he was in favor of the existence of a Parliament in Germany; he reproached himself for his desire to overcome internal difficulties by moving abroad.

Bismarck's first appearance before the members of the Budget Committee did not exactly help to make a good impression. He spoke of reconciliation, but also stated that the legal problem raised could become a question of power; Germany had its eyes not on Prussian liberalism, but on its might:

Prussian borders set by the Vienna Treaty do not favour a healthy development of the State; the great problems of the time will not be solved by speeches and decisions made by a majority—this was the tremendous error of 1848 and 1849—but with iron and blood.

German unity for the benefit of Prussia

Bismarck is dedicated to a fundamental objective: to achieve unity for the benefit of Prussia and to the exclusion of the Austrian Empire. To achieve this he used the formation of a strong ministry that governs overcoming the criticism of the liberal opposition, the perfect reorganization of a powerful army under the leadership of Helmuth von Moltke, diplomatic action to guarantee the pro-Prussian neutrality of France and Russia, and achieve the diplomatic isolation of the Austrian Empire. To make it possible it was necessary to carry out three successive wars between 1864 and 1870:

- War against Denmark (1864). The first occasion was raised on the occasion of the question of Schleswig and Holstein's ducats against Denmark in 1864. In the face of the will of the king of Denmark to incorporate these ducats into his kingdom, Bismarck calls upon the Diet of Frankfurt to intervene militarily. The rapid victory of Austria and Prussia implies that Schleswig is under Prussian administration and Holstein under the Austrian empire. But differences will soon arise between the two administering States.

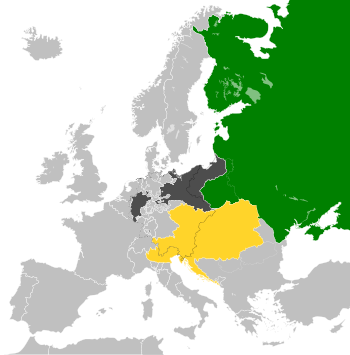

- War against Austria (1866). Given the differences in the administration of the ducats, Bismarck meets with Napoleon III to achieve the neutrality of France and ensures the alliance of Italy that aspires to the incorporation of Venice. In June 1866, Bismarck called for the exclusion of the Austrian Empire from the Confederation and occupied Holstein. This fact triggers war. The initiative and victories for the Prussians and their allies. The battle of Sadowa (or Sadova) on July 3, 1866, allowed considerable progress in the process of German unification, consolidating Prussian hegemony within the German states to the detriment of the Austrian Empire. The peace of Prague, signed in August 1866, represents an important turning in the history of Germany: Prussia is annexed Hannover, Hessen Frankfurt and the duchess of Schleswig and Holstein; the Austrian Empire recognizes the dissolution of the German Confederation and its exclusion from the German State; Italy, for its part, obtains from the Austrian Empire the transfer of the territory of Venice, also concludes At that time, July 1867, the German Confederation encompasses 23 German states under Prussian hegemony. The Constitution gave a federal structure in the union, its president was King William I of Prussia, the Federal Chancellor was Bismarck, and had a House chosen for universal suffrage with limited powers, and a federal council where the princes and cities of the union were represented, the federal government resided in Berlin, the army followed the Prussian model and the Constitution assured Prussia's predominance in the Confederation. With these measures the economic and military unity of small Germany of 1848 was already carried out around Prussia, but political unity was only achieved after the war against France.

- Franco-Prussian War (1870). The occasion for the conflict was presented on the occasion of the candidacy Hohenzollern to the vacant throne of Spain, where Bismarck manoeuvres to get Napoleon III to appear as an aggressor. On July 17, 1870, France declared war to Prussia and the allied German states of the South. The war takes place between August 1870 and January 1871, and constitutes a total victory of Bismarck: France was diplomatically isolated and with an ill-prepared army, while Prussia had a magnificent well-organized army under the direction of Helmuth Mol vontke and, in addition, has the support of the German States of the South. The development of war is totally favorable to Prussia. After the battle of Sedán Napoleon III chapter.

Bismarck, with the Franco-Prussian war, achieved his goal: to create the German Empire (1871) with the integration of the southern states with the rest. On January 18, 1871, the German Empire was proclaimed at Versailles and William I, Emperor of the unified Germany, with Bismarck as Chancellor. The defeated France is reorganized as a Republic and signs the Frankfurt peace treaty which stipulates the cession of Alsace and Lorraine to the new German state, the payment of war indemnities and a guarantee with the German military occupation of the north-eastern departments. In 1871 German hegemony over the European continent was established and the imperial constitution of 1871 set the characteristics of the new Empire: the territorial delimitation with the federal union of all the States, the political and administrative institutions, the principles and aspects of federalism and unit. Germany becomes great: Berlin concentrates the political life of the new State and acts as one of the great political capitals of Europe, economic development intensifies until the new State is one of the great industrial and capitalist giants, and in international politics the so-called Bismarckian systems prevail.

The Creation of the German Empire

The German chancellor focused his attention on the balance within the European continent, while the rest of the great powers oriented their activity towards the formation of a colonial empire. Bismarck's initial opinion was against colonial enterprises for which Germany had no naval potential to control. On the other hand, while some powers considered colonizing activity as a formula to soften demographic pressure, Bismarck viewed migration with suspicion, and considered that a large population in the metropolis was essential to maintain a relevant role on the international scene. The economic advantages were not evident either and, above all, friendship with the United Kingdom, an essential requirement of the continental diplomatic system, could cool down if colonial tensions appeared. On the other hand, the colonialist requests formulated by the Hamburg merchants since the 1860s could not be ignored. And, furthermore, at the end of the 1870s, the economic crisis, social tensions and greater pressure (such as the Colonial Society, for example) prompted the chancellor to review his position, but noting that it should be a limited expansion, and that did not imply financial commitments for the State.

German colonizing activity is taking place in four areas: the Gulf of Guinea with the protectorate of Togo and Cameroon; in southwestern Africa, the exploitation of copper mines is projected; in Eastern Africa the regions located in front of the island of Zanzibar are covered; In Oceania, sovereignty is proclaimed over northeastern New Guinea and the New Britain archipelago, named the Bismarck Archipelago after the chancellor. The Berlin Conference in the years 1884-1885 defines the colonial rights and regulates the domains over the basins of the great rivers, and above all, the Congo River. Bismarck stands as the arbiter of colonial issues, but at the price of cooling relations with London and bringing the British government closer to the French.

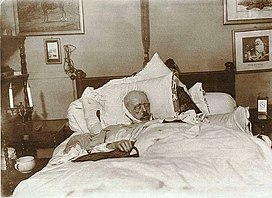

Last years