Otomi people

The Otomi are a people of Mexico who inhabit a discontinuous territory in central Mexico. It is linguistically related to the rest of the Ottomanguean-speaking peoples, whose ancestors have occupied the Neovolcanic Axis since several millennia before the Christian era.[citation needed]

Currently, the Otomi inhabit a fragmented territory that goes from the north of Guanajuato, to the east of Michoacán and to the southeast of Tlaxcala. However, most of them are concentrated in the states of Hidalgo, Mexico and Querétaro. According to the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples of Mexico, the Otomí ethnic group numbered 667,038 people in the Mexican Republic in 2015, which makes them the fifth largest indigenous people in the country[citation required].

Of them, only a little more than half spoke Otomi. In this regard, it can be said that the Otomi language presents a high degree of internal diversification, so that the speakers of one variety often have difficulties understanding those who speak another variant.

Hence, the names by which the Otomi call themselves are numerous: ñätho (Toluca Valley), hñähñu (Mezquital Valley), ñäñho (Santiago Mezquititlán in southern Querétaro) and ñꞌyühü (Sierra Norte de Puebla, Pahuatlán) are some of the demonyms that the Otomi use to call themselves in their own languages, although it is frequent that, when they speak in Spanish, they use the ethnonym otomí, of Nahuatl origin.

Origin of the Otomi demonym

Most of the ethnonyms used to refer to the indigenous peoples of Mexico, the term otomí is not native to the people to which it refers. Otomí is a term of Nahuatl origin that derives from otomitl, a word that in the language of the ancient Mexicas means who walks with arrows, although authors such as Wigberto Jiménez Moreno have translated it as bird flechador.

Ethnic territory

The ethnic territory of the Otomi has historically been central Mexico. Since pre-Hispanic times, Oto-Manguean-speaking peoples have inhabited that region and are considered native peoples of the Mexican highlands. According to Duverger's calculation, the Otomanguean peoples may have been in Mesoamerica at least since the beginning of the sedentarization process, which took place in the eighth millennium BC.

The Otomanguean occupation of central Mexico then refers to the fact that the linguistic chains between the Otomanguean languages are more or less intact, so that the linguistically closest members of the family are also close in the spatial sense. The first fracture of the Otomanguean group occurred when the eastern languages separated from the western languages. The western arm is made up of two large branches: the Tlapaneco-Manguean-speaking peoples and the Oto-Pame-speaking peoples. Among the latter are the Otomi, settled in the Mexican Neovolcanic Axis along with the rest of the peoples that are part of the same Otomanguean branch (Mazahuas, Matlatzincas, Tlahuicas, Chichimecas Jonaces and Pame).

The Otomi currently occupy a fragmented territory that spans the states of Mexico, Hidalgo, Querétaro, Guanajuato, Michoacán, Tlaxcala, Puebla, and Veracruz. All these states are located in the heart of the Mexican Republic and concentrate the majority of the country's population. According to the spaces with the highest concentrations of Otomí population, this town can be grouped into four aspects: the Mezquital Valley, the Sierra Madre Oriental, the Queretaro Semidesert and the north of the state of Mexico.

Isolated from these large groups that make up around 80% of the total members of this indigenous people are the Otomi of Zitácuaro (Michoacán), those of Tierra Blanca (Guanajuato) and those who still remain in Ixtenco (Tlaxcala). Due to the territory in which they are located, the Otomi live in an intense relationship with the large metropolises such as the Metropolitan Area of Mexico City, the city of Puebla, Toluca, the western part of the city of Pachuca, Santiago de Querétaro and the capital of San Luis Potosí, places where many of them have had to emigrate in search of better job opportunities.

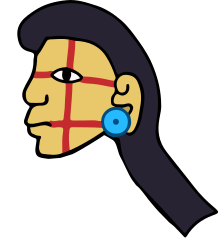

In each state, women's and men's clothing varies according to weather conditions:

The traditional clothing of the women of the Otomi group in the State of Mexico consists of a very wide and long chincuete or tangle of wool or blanket, like a skirt, white in color, blue, yellow, black, with green, orange and yellow lines; and a short-sleeved white blanket or poplin blouse with flower embroidery. The use of quexquémetl, made of cotton or wool in various colors, is characteristic of Otomi clothing, and all clothing is adorned with embroidered floral decorations.

Women's clothing in the state of Tlaxcala consists of a wool thumbtack that is usually black, an embroidered blouse with floral and animal motifs on the neck and on the arms of the blouse. The embroidered girdle is used to hold the chincuete, the rebozo and the huaraches.

History

Historiographical texts on the Mesoamerican peoples of pre-Hispanic times have paid very little attention to the history of the Otomi. Many centuries ago, in the territory that the Otomi occupied when the Spanish arrived, great cities like Cuicuilco, Teotihuacán and Tula flourished. Even in the Triple Alliance that dominated the so-called Mexica Empire, Tlacopan inherited the domains of Azcapotzalco, with a majority of the Otomi population.

However, the Otomi are almost never mentioned as protagonists of pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican history, perhaps because the ethnic complexity of central Mexico at that time makes it impossible to distinguish the contributions of the ancient Otomi from those produced by their neighbors. Until recent years, some interest began to appear in the role that this town played in the development of the high cultures of the Neovolcanic Axis, from the Preclassic Period to the Conquest.

The Otomi peoples in pre-Hispanic times

Around the fifth millennium BC. C., the Otomanguean-speaking peoples formed a great unit. The diversification of languages and their geographical expansion from what has been proposed as their urheimat, that is, the Tehuacán Valley (currently in Puebla) must have occurred after the domestication of the agricultural trinity Mesoamerican, composed of corn, beans and chili.

This is established based on the large number of cognates that exist in the Otomanguean languages in the repertoire of words alluding to agriculture. After the development of an incipient agriculture, the Proto-Otomanguean legion gave rise to two distinct languages that constitute the antecedents of the current eastern and western groups of the Otomanguean family.

Continuing with the linguistic evidence, it seems probable that the Oto-Pame (members of the western branch) arrived in the Basin of Mexico around the fourth millennium before the Christian era and that, contrary to what some authors maintain, have not migrated from the north but from the south.

In this sense, it is plausible that for a long time the population of central Mexico has been part of the family of peoples who speak Otomanguean languages. From the Preclassic (25th century BC - 1st century AD), the Otopamean linguistic group began to fragment more and more, in such a way that by the Classic Period, Otomi and Mazahua were already different languages.

If the linguistic chains of the Otopame group are concentrated and more or less intact in central Mexico, it is possible that the Otomanguean groups have occupied their current ethnic territories for a long time, which would lead to a reassessment of their participation in the flourishing of populations such as Cuicuilco, Ticomán, Tlatilco, Tlapacoya and others during the Preclassic Period; but especially in the development of the great city of Teotihuacán. Although there are several authors who agree that the population of the Valley of Mexico during the flowering of Teotihuacán was mainly Ottoman, they are reluctant to accept that the rulers of the metropolis could also be part of the same linguistic group.

The fall of Teotihuacán is a milestone that marks the end of the Classic in Mesoamerica. Changes in political networks at the Mesoamerican level, disputes between small rival states, and population movements resulting from prolonged droughts in northern Mesoamerica facilitated the arrival of new settlers in central Mexico. Around this time the arrival of large Nahuatl-speaking groups took place that began to displace the Otomi to the east. They then reached the Sierra Madre Oriental and some areas of the Puebla-Tlaxcala valley. In the following centuries, large states headed by the Nahua peoples developed in the Otomi territory. Around the 9th century, the Toltecs turned Tula (Mähñem'ì in Otomí) into one of the main cities of Mesoamerica. This city concentrated a good part of the population of the Mezquital Valley, of Otomí affiliation; although many of them continued to live to the south and east, in the state of Mexico and the Sierra Madre Oriental.

The flourishing of the Tepanec state of Azcapotzalco in the lake basin of the Valley of Mexico led this people to expand westward, occupying the territory that had traditionally been occupied by the Otomi, Mazahua, Matlatzinca and Atzinca peoples. In this way, the Ottoman towns fell into the orbit of power of the Nahuas who had occupied the basin of Mexico. After the defeat of Azcapotzalco before the alliance of Mexico-Tenochtitlan and Texcoco, the domains of the Tepanecs in the west of the current state of Mexico were assigned to Tlacopan. The territory of the Otomi was precisely in the area where the domains of the Mexica and their allies to the east and the Tarascans of Michoacán to the west converged. When the Spanish arrived in central Mexico, this area was inhabited by various ethnic groups that often mixed to form a town. That is why the chroniclers of the Indies reported that Otomi, Nahuatl, Chocho, Matlatzinca and Mazahua were spoken in Tlacopan. Wright Carr notes that:

Far from being a dominated people, the Ottomans were an essential part of the political, cultural, military, economic and social landscape of the Center of Mexico.

Conquest

The Otomi entered the history of the Conquest of Mexico when the Spanish arrived in the region dominated by the Tlaxcalans. As previously stated, the Otomi arrived in the Puebla-Tlaxcala region during the Early Postclassic period, when their original territory was invaded by the Nahuas from western and northern Mesoamerica. In the Tlaxcala valley region they lived with the manors of the so-called "Señorío de Tlaxcala", a confederation dominated by Nahua tribes and opposed to the Mexicas and their allies. The Tlaxcalans were military allies of the Tecóac Otomi, who were recognized as a people with great war skills. According to the Florentino Codex the Otomi were attacked by the Spanish:

And when they came to Tecoac, it was in the land of Tlaxcaltecas, where they were populating their Ottomans. For these Ottomans came to meet them in war, and with shields they welcomed them.

But Tecoac's ottotes were very well ruined, they totally beat them. They divided them into bands, there was division of groups. They were clothed, they were besieged with the sword, they were arrows with their bows. And not a few alone, but all perished.

And when Tecoac was defeated, the Taxcaltecas heard him, they knew: they were told. A lot of them were intimidated, they felt like death. They overtook great fear, and were filled with fear.

According to the version of Bernardino de Sahagún's informants, upon seeing the ruin of the Otomi of Tecóac, the Tlaxcalans decided to ally with the Spanish.

In fact, the Otomies played a very prominent role; but little recognized in the Conquest of Mexico. After the defeat of the army of Hernán Cortés in the episode of the Sad Night, the Otomi from the town of Teocalhueyacan visited Cortés a day later in the direction of Naucalpan. In this meeting, the Spaniards received food and a promise of alliance and refuge in the Teocalhueyacan area. The Spaniards visited this town and remained there for about ten days, rebuilding military forces and political alliances.

At the behest of this group of Otomi, Cortés made a surprise attack and massacred the Nahuas of Calacoaya on July 2, 1520, allies of the Triple Alliance and enemies of the Otomi. This was the second military action of the Spanish in the Valley of Mexico, this time successful and counting on the complicity of the Otomi of Teocalhueyacan. After compiling themselves, the Spaniards left for the allied territory of Tlaxcala; but on the way they faced the Mexicas again in the Battle of Otumba. On this occasion they were victorious and for this they most likely had to count on the help of the Otomi, both from Tlaxcala and from Teocalhueyacan.

Colonial period

The Otomi were Christianized in the years following the Conquest of Tenochtitlán. The first tasks of evangelization were carried out by the Franciscans, concentrated in the provinces of Mandenxhí (Xilotepec) and Mäñhemí (Tula), where they carried out their work between the years of 1530 and 1541. In 1548 the order of the Augustinians approved the creation of the convents of Atocpan and Ixmiquilpan.

The convent of Ixmiquilpan stands out because its murals (carried out in the second half of the 16th century) present a clearly indigenous theme (that of the sacred war) in a panorama of elements related to Christian mythology. With the Christianization of the Otomi also began the process of adapting to the European forms of political organization, which gave rise to the organization of indigenous communities in stewardships, which, in cases such as that of the Otomi of Ixtenco (Tlaxcala) constitute one of the few elements of ethnic identity that they still retain.

Parallel to this process of acculturation, in other parts of central Mexico, the Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún made inquiries among the Nahua peoples. Sahagún's informants exposed the way in which the Nahuas viewed the Otomi before the arrival of the Spaniards, of whom they said "they did not lack police, they lived in towns; they had their republic".

The Franciscan friars built a large convent, the Corpus Christi convent, in Tlalnepantla in 1550 and one of its side doors called porciúncula reads that it was built equally by the local Nahua and Otomi people now Christianized and equally subjected to the Spanish crown. This convent was built on a site that was halfway between the two large towns of Tenayuca (Mexica) and Teocalhueyacan (Otomi). The teocalli of Tenayuca survives to the present day; but not that of Teocalhueyacan. Given that it is known that the stones contributed for the construction by the Otomi were gray, it is possible that these are precisely the stones of the disappeared Teocalhueyacan teocalli, paradoxically those of Teocalhueyacan were one of the first allies of Cortés in the Valley of Mexico.

During the Colony, the friars did a great deal of research on indigenous cultures and languages. However, compared to the case of the Nahuatl-speaking peoples, the documents produced about the Otomi are really few. Luis de Neve y Molina published in 1797 some Rules of orthographia, dictionary, and art of the Othomi language, which were rediscovered in 1989. This document joins other manuscripts that were produced in advance at the center of Mexico. Perhaps the best known of them is the Huamantla Codex, which was made in the Tlaxcala region in the century. XVI and talks about the history of the Otomi from pre-Hispanic times to the Conquest. Another equally important document is the Códice de Huichapan, from the Mezquital Valley and made by the Otomi Juan de San Francisco at the end of the XVI.

The arrival of the Spanish in Mesoamerica meant the submission of indigenous peoples to the domination of the newcomers. By the 1530s, all the Otomi communities of the Mezquital Valley and the Barranca de Meztitlán had been divided into parcels. Subsequently, when Spanish legislation was modified, the so-called republics of Indians appeared, systems of political organization that allowed certain autonomy of the Otomi communities with respect to the Hispanic-mestizo populations. The creation of these republics of Indians, the strengthening of the indigenous councils and the recognition of the possession of communal lands by the Spanish State were elements that allowed the Otomi to preserve their language and, to a certain extent, their indigenous culture. However, especially with regard to land possession, the indigenous communities suffered dispossession throughout the three centuries of Spanish colonization.

At the same time that the Spanish were occupying the old Otomi settlements (as is the case of the current city of Salamanca (Guanajuato), founded in the Otomi settlement of Xidóo ("Place of Tepetates") in 1603 by decree of Gaspar de Zúñiga y Acevedo, viceroy of New Spain), some Otomi families were forced to accompany the Spanish in the conquest of the territories to the north of Mesoamerica, occupied by the warlike Arido-American peoples. The Otomíes were colonizers who settled in cities like San Miguel el Grande and other cities of El Bajío. In fact, the colonization process of this territory was essentially the work of the Otomi, spearheading the Xilotepec domain.

In El Bajío, the Otomi served as a bridge for the sedentarization and Christianization of the nomadic peoples, who ended up being assimilated or exterminated by force. The importance of El Bajío in the economy of New Spain made it a scenario where different ethnic groups later converged, including migrants from Tlaxcala, the Purépecha and the Spanish, who would eventually overcome all the indigenous groups that supported them in the conquest of this territory that had been the habitat of numerous peoples classified as chichimeca.

However, until the 19th century, the Otomi population in El Bajío was still a major component, and some of their descendants remain in municipalities such as Tierra Blanca, San José Iturbide, and San Miguel de Allende. Population movements Otomi continued throughout the entire colonial era. For example, in San Luis Potosí, a total of 35 Otomi families were forcibly taken to occupy the periphery of the city and defend it from attacks by the region's indigenous nomads in 1711. In several places, the Otomi population was decimated not only by forced or consented migrations, but also by the constant epidemics suffered by the Mesoamerican indigenous people after the Conquest. Numerous communities were devastated between the 16th and XVIII due to illness.

During the 17th century there were some conflicts between Spaniards and indigenous people. For example, in 1735 in Querétaro (whose Otomi population had been assimilated or relegated from the better quality lands due to the push for the Spanishization of El Bajío) there was a rebellion in the capital of the province due to the scarcity of grains for the population.

Between 1767 and 1785, the Otomi of Tolimán attacked neighboring haciendas that had dispossessed the indigenous community of their land. The tension caused by the reoccupation of the lands that the landowners had obtained by invading the lands of the communities led to a new conflict in the Tolimán region in 1806. In order to put an end to the dispute, it was necessary for the Corregidor of Querétaro intervene and imprison the leaders of the rebellion. However, only two years later violence broke out again in Tolimán, and the indigenous people reoccupied the lands from which they had been dispossessed.

19th and 20th centuries

In general, the indigenous people of Mexico remained indifferent to the War of Independence, in the Mezquital Valley several insurgents managed to ally themselves with the Otomí groups of the area, who saw in the rebellion a way to get rid of the domination of the peninsulars, who had appropriated large tracts of land in the valley and other areas of the current state of Hidalgo where the Otomi were settled.

It was Otomi who supported Julián Villagrán and José Francisco Osorio, who controlled northern Mexico for several years at the beginning of the war. At the end of the war, the country was involved in a series of internal rebellions that also dragged down the indigenous peoples. The liberal reforms of the governments of Valentín Gómez Farías and Benito Juárez caused the loss of the legal personality that the indigenous communities had had during the Colony. The application of the land confiscation laws caused an agrarian conflict in the north of the state of Mexico (currently corresponding to the territory of Hidalgo) from Huejutla to Meztitlán, carried out by the Otomi and Nahua communities who found themselves dispossessed of their lands.

Language

The Otomi languages are part of the Otomanguean linguistic family, one of the oldest and most diverse in the Mesoamerican area. Among the more than one hundred Ottomanguean languages that survive today, the Otomi languages have their closest relative in the Mazahua language, also spoken in the northwest and west of the state of Mexico. Some glottochronological analyzes applied to the Otomi languages indicate that the Otomi separated from the Mazahua language around the 8th century of the Christian era. Since then, the Otomí fragmented into the languages that are currently known.

The native language of the Otomi is that they call each other the Otomi language. In reality, it is a complex of languages, the number of which varies according to the sources consulted. According to the Ethnologue of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, and with the Catalog of indigenous languages of the National Institute of Indigenous Languages (INALI) of Mexico, there are nine varieties of Otomi.

David Charles Wright Carr proposes that there are four Otomi languages. According to the National Institute of Indigenous Peoples (INPI), only 50.6% of the Otomí population speaks the native language of this group. In 1995, this proportion corresponded to a total of 327,319 speakers of the Otomi languages in the entire Mexican Republic.

The previous calculation corresponds to a calculation by the INPI in which it is intended to include children under five who speak Otomi, who are not included in Mexican population counts. According to the I Population Count of 1995, Otomi speakers over five years of age totaled 283,263 individuals, which represents a loss of 22,927 speakers compared to the 1980 Population and Housing Census, when 306,190 speakers of languages were registered. otomi.

The Otomi language-speaking population has decreased in recent years. In a certain way, this reduction in Otomi speakers is due to migration from the communities of origin and the urbanization of their ethnic territory, which imposes the need for them to live with an exclusively Spanish-speaking population. The contraction of the Otomi linguistic community is also the result of the Spanishization processes to which all the indigenous peoples of Mexico have been subjected. The hispanicization of indigenous people in Mexico has long been understood as a subtractive process, that is, it implies renouncing the use of the mother tongue in order to obtain linguistic competence in the Spanish language.

The hispanicization of the indigenous people was presented as an alternative to integrate the indigenous people into the Mexican national culture and to improve their living conditions. However, indigenous education programs in the Spanish language have been discredited by critics because, on the one hand, they imply the loss of the native language and, on the other hand, they have not served to improve the quality of life of indigenous communities.

References and notes

- ↑ a b « Ottomans – Statistics - Atlas of the United Peoples of Mexico. It was squealing." Government of Mexico. Archived from the original on October 24, 2019. Retrieved October 24, 2019.

- ↑ For ethnic population members of ethnic minorities living in a national state are understood to be not recognized as multi-ethnic. In this regard, the ethnic population includes not only the speakers of a language—in this case, the otomi—but also those who have stopped using the language but are recognized as members of the group and are recognized as such, whether conventional or officially. According to the criteria chosen by Mexican government agencies to calculate the number of indigenous people, they are part of the indigenous population Mexican members of families where the head of family or his spouse are indigenous speakers (Del Val, 2000: 55).

- ↑ Lately some speakers of the Mezquital Valley have begun to consider the ethnonymous "otomi" as derogatory. This does not occur in other variants and should therefore continue to be used. It is also the most widely used term in the Spanish-speaking world in all spheres. In this regard, echoing the words of David C. Wright (2005: 19): "While the word 'otomi' has been used in texts that despise these ancient inhabitants of the Center of Mexico, I think it is convenient to use the same word in the works that try to recover their history; instead of discarding it I propose to vindicate it."

- ↑ Gómez de Silva, 2001.

- ↑ Barrientos López, 2004:6.

- ↑ For Ethnic territory is understood that space that serves as a reference to the identity of a people, a space with which a people is related by their history and beliefs, to inhabit it and because it is considered the origin of the same people (Velázquez, 2001; referred to in Bello Maldonado, 2004:101)

- ↑ Duverger, 2007: 40.

- ↑ a b Wright Carr, 2005: 26.

- ↑ [1] Ottomans, Government of the State of Mexico.

- ↑ Wright Carr, 2005: 28.

- ↑ Urheimat is a German term that designates the site that is considered the geographical area of origin of a protolengue.

- ↑ Campbell, Lyle (1997). «American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America». Oxford Studies in Anthropological Linguistics (in English) (New York: Oxford University Press) (4).

- ↑ a b Wright Carr, 1996.

- ↑ Moreno Alcántara et al.2002: 7.

- ↑ Wright Carr, 2005: 29.

- ↑ There are other historiographic proposals that propose that the otomi occupation of the Tlaxcala region may have had a more ancient origin. Although it does not deny the migratory movements of the ottoids derived from the Nahuas arriment to the center of Mexico, Serra Puche (2005: 25) points out that the inhabitants of Xochitécatl (city that flourished in the Preclassic) could be Ottomans, based on four points: the presence of numerous furnaces, the settlement pattern that gives preference to the elevated places, subsistence supported in the forage and the

- ↑ Leon Portilla, Cap. V.

- ↑ Wright Carr, 2005: 43.

- ↑ The full description appears in Sahagún, 2000: cap. XXIX.

- ↑ Lastra, 2005: 33-37.

- ↑ Moreno Alcántara et al., 2002: 7-10.

- ↑ Acosta Sol, s/f: 62.

- ↑ Wright Carr, David Charles (1999). The conquest of the Bajío and the origins of San Miguel de Allende. Mexico: Universidad del Valle de México and Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- ↑ Acosta Sol, s/f: 63. It should be noted that the Ottomans were not the only indigenous migrants in colonial times. The tlaxcaltecas, allies of the Spaniards, agreed to accompany these in their campaign to the north. The descendants of the Tlaxcalteca migration are in several villages of the Mexican border states, such as Bustamante (New Lion).

- ↑ Moreno Alcántara, 2002: 10.

- ↑ CIESAS, s/f b

- ↑ Moreno Alcántara, 2002: 12.

- ↑ Wright Carr, 2005: 27.

- ↑ SIL, 2005; Inali, 2008: 41-54.

- ↑ CDI, 2000.

- ↑ Garza Cuarón and Lastra, 2000: 165.

- ↑ Hamel et al.2004: 87.

- ↑ Hamel et al.2004: 86.