Orphism

The orphism (infrequently called orphicism; in ancient Greek: Ὀρφικά, romanized: Orphiká) is the name given to a set of religious beliefs and practices, a religious current of ancient Greece and the world Hellenistic, as well as among the Thracians, associated with literature attributed to the mythical poet Orpheus, master of enchantments, who descended into the Greek underworld and returned. As it possesses elements typical of mystery cults, it is also often referred to as Orphic mysteries.

The Orphics revered Dionysus (who once descended into the underworld and returned) and Persephone (who descended annually into the underworld for a season and then returned). Orphism has been described as a reform of the earlier Dionysian religion, involving a reinterpretation or rereading of the myth of Dionysus and a reordering of Hesiod's Theogony, based in part on pre-Socratic philosophy.

The central axis of Orphism is the suffering and death of the god Dionysus at the hands of the Titans, which forms the basis of the central myth of Orphism. According to this myth, the child Dionysus is killed, torn to pieces, and consumed by the Titans. In revenge, Zeus strikes the Titans with lightning, turning them to ash. From these ashes humanity is born. In the Orphic belief, this myth describes humanity as possessing a double nature: the body (in ancient Greek: σῶμα, romanized: sôma), inherited from the Titans, and a divine spark or soul (in ancient Greek: ψυχή, romanized: psukhḗ), inherited from Dionysus. To achieve the salvation of the titanic and material existence, one had to be initiated into the Dionysian mysteries and undergo teletē, a ritual purification and relive the suffering and death of the god. eternity with Orpheus and other heroes. They believed that the uninitiated (Ancient Greek: ἀμύητος, romanized: amúētos), they would reincarnate indefinitely.

To maintain their purity after initiation and ritual, the Orphics attempted to lead an ascetic life free from spiritual contamination, primarily by adhering to a strict vegetarian diet that also excluded broad beans.

Introduction

The Orphic movement represents a confrontation with the religious traditions of the Greek city and, ultimately, a new conception of the human being and his destiny. Under the name of the mythical Orpheus, singer and tragic traveler from the Beyond, a series of texts preach and attest to this new religiosity, a doctrine of salvation about man, his soul and his destiny after death.

Orphism works exclusively on a religious plane. It is a sect that questions the official religion of the Hellenic peninsular cities, particularly at two levels: one of theological thought, the other of practices and behaviors. Orphism is, fundamentally, a religion of texts, with the cosmogonies, theogonies and interpretations that these do not cease to produce. Essentially, all this literature seems to have been elaborated against the dominant theology of the Greeks, that is, that of Hesiod and his Theogony. Since orphism is a literature that is inseparable from a genre of life, the break with official thought entails no less great differences in practices and behaviors. The one who chooses to live in the Orphic way, the bíos orphikós, presents himself, first of all, as an individual and as an outcast. He is a wandering man, similar to those Orpheus-Telestes who go from city to city, proposing his recipes for salvation to individuals, walking around the world like the demiurges of the past. Members of a sect outside of politics, people of sacred books and texts, and at the same time practitioners of their mysterious rites and a peculiar asceticism (with strict precepts such as not eating meat or spilling animal blood or wearing linen fabrics)., the Orphics left a long mark in several texts, but also important echoes in many different authors, especially in some philosophers.

Origins

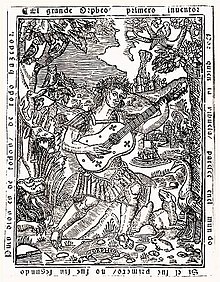

Orphism is named after the legendary poet-hero Orpheus, who is said to have originated the Dionysian Mysteries. Orpheus, however, was more associated with Apollo than Dionysus in early sources and iconography. According to some versions of his myth, he was the son of Apollo and, during his last days, eschewed the worship of other gods, devoting only Apollo. Orpheus is numbered among the Argonauts as early as the VI a. C., a generation before the Trojan War. It is unknown if there was an actual historical model for this mythical figure and if the Orpheus legend has a historical core. Opinions differ among researchers.

Orphism probably originated in Thrace, considered the homeland of Orpheus and a nation the Greeks called barbarian. It spread in Greece—concentrating in northern Greece and Crete—in areas of southern Italy settled by Greek settlers, and on the Black Sea coast populated by Greeks. Poetry containing clearly Orphic beliefs has been traced to the VI century BCE. C.. or at least the century V a. C., and graffiti from the V century a. C. seem to refer to the "Orphics". The Derveni Papyrus allows Orphic mythology to be dated to the late V century a. C., and is probably even older.

Explanations of origins and early development discussed in the research are speculative. Orphic ideas and practices are attested by Herodotus, Euripides, and Plato. Plato refers to the "initiators of Orpheus" (Ὀρφεοτελεσταί), and associated rites, although it is uncertain to what extent "Orphic" literature in general was related to these rites. In particular, the relationship of the Orphism with related phenomena within Greek religion, such as Pythagoreanism, the Eleusinian Mysteries, various manifestations of the cult of Dionysus and the religious philosophy of the pre-Socratic Empedocles. In the V century a. C., Herodotus reported on the prohibition of being buried in woolen clothing, a burial rule called "Bacchic" (Dionysiac) and Orphic. Empedocles, who also lived in the V a. C., seems to have been Orphic. According to a research hypothesis, he not only relied on Orphic ideas for the content of his poetry, but also formally relied on an Orphic model.

Relation to Pythagoreanism

Orphic ideas and practices have parallels with elements of Pythagoreanism, and various traditions hold that the Pythagoreans or Pythagoras himself were the authors of the first Orphic works; alternatively, later philosophers believed that Pythagoras was an initiate of Orphism. The degree of influence of one movement over the other remains a matter of debate. Some scholars argue that Orphism and Pythagoreanism began as separate traditions that were later merged and combined due to some similarities. Others argue that the two traditions share a common origin and can even be considered a single entity, called "Orphism-Pythagoreanism".

Orphic Writings

The rich book production of the Orphics, attested as early as the V century B.C. C., continued until late antiquity. What is characteristic of the Orphics is, on the one hand, their great esteem for their books and, on the other, the fact that they apparently did not permanently fix their doctrinal texts as binding in a specific version, but continually reformulated and interpreted them. These are mainly mythical descriptions of the creation of the world (cosmogony) and hymns.

Orphic poetry, the writing of the Orphics in verse form, whose author was once considered Orpheus himself, has been largely lost. Some poems exist in their entirety, while other parts of Orphic poetry have only survived in fragments or are known from summaries of their content, while of other works only their titles have survived. The Suda, a Byzantine encyclopedia, includes several titles. This list probably comes from a lost treatise on Orphic poems written by the grammarian Epigenes during the Hellenistic period. The meter of the verse of Orphic poetry is always hexameter.

A collection of Orphic hymns has been preserved in its entirety. It is about 87 poems, whose length varies between six and thirty verses. In them, Orpheus, as a fictional author, glorifies the deities worshiped by the Orphics. These poems were probably created in the 2nd century century for a cult community in Asia Minor, perhaps using older material.

The following poems have only survived in fragments or are known from summaries of their content:

- The ancient Orphic Theogony, a poem that deals with the origin of the cosmos, the gods and the humans. It is said that the peripathetic Eudemo of Rhodes, who lived in the centuryIVa. C., wrote a reproduction of the content. The neo-platonic philosopher Damascus, of late antiquity, refers to him and outlines various variants of myth.

- The "Sacred Discourses"Hieroi lógoi) in 24 raptures." They also describe the mythical prehistory of the cosmos. 176 fragments have been preserved. The dating of the text, from which the remaining fragments come, varies between the end of the centuryIIa. C. and the centuryIId. C. The lost original version was probably written in the first time of orphanism.

- Only one hymn is known to Zeus, quoted by the Neoplatonic Porfirio, and another to Dioniso, who is repeatedly referred to by the scholar of late Macrobio antiquity in his "Saturnalia». In the centuryII, the writer Pausanias reported on the hymnical songs composed of Orpheus and tuned by the Licomides, members of an Athenian priestly dynasty, in their rites. Pausanias thought Orpheus' hymns were only surpassed in beauty by Homer's.

- the «Orphic Archaetics» (Orphéōs Argōnautiká «The Argonautical Journey of Orpheus»), a poem of late antiquity of 1376 hexameters. In this version of the Argonautas saga, Orfeo narrates the journey of the Argonauts. He himself plays an important role in the group of heroes who undertake an adventure journey on the Argo ship to capture the Golden Vellocino. Although Orfeo is already of advanced age, the company could not succeed without it. The Argonauts depart from their Greek home and travel first to Colquida, on the eastern shore of the Black Sea, where they acquire the hair. On their return journey, they cross the river Tanaïs (Don) to the north end of the Eurasian continent. There they reach the Ocean, the river that flows into a ring around the inhabited world. Then they turn westward and circumnavigate first the north and then west of Europe; the way back home passes through the Strait of Gibraltar.

The Derveni Papyrus, a scroll found in 1962 in tomb A of the Derveni tombs near Thessaloniki, contains fragments of a commentary on an unknown version of the Orphic creation myth, from which the commentator quotes individual verses which he interprets allegorically. In this version, Zeus plays the main role as creator. The commentator emphatically distances himself from what he considers to be a superficial and literal misunderstanding of the text. The papyrus was inscribed in the IV century BCE. C., the commentary dates to the late V or early IV a. C. and the annotated poem is probably much older still.

Lost writings include the “oracles” (chrēsmoí), the “consecrations” (teletaí), the “kraters” (kratḗres), the “cloak” (péplos), the “net” (díktyon), the “physics” (physiká, on cosmology) and "astrology" (astrologiká).

Beliefs

The Orphics were interested above all in the origin of the cosmos, the world of the gods and humanity, and the fate of the soul after death. His way of thinking and expressing himself, mythical and poetic, meant that his teachings were not fixed and dogmatized in a clear and binding way, but rather maintained a fluctuating character and open to different interpretations.

Soul Doctrine

The Orphic creed proposes an innovative interpretation of the human being, as composed of a body and a soul, an indestructible soul that survives and receives rewards or punishments beyond death. A precedent can be found in Homer, and already in his epics the opinion appears that there is an animating principle in human and animal existence whose presence is a requisite for life and which survives the death of the body. According to the ideas transmitted by Homer, this entity, the "soul" (in Greek psychḗ), separates from the body at the moment of death and goes to the underworld as its shadowy image. The poet assumes that the existence of the soul after death is unpleasant; makes her lament her fate. However, in Homer the body was the true self of man, while for the Orphics the soul is essential, which the initiate must always take care of and strive to keep pure for his salvation. The body is a mere dress, a temporary dwelling, a prison or even a tomb for the soul, which in death detaches itself from that earthly envelope and goes to the afterlife to receive its rewards or its punishments, which may include some reincarnations or metempsychosis in other bodies (and not only humans), until they achieve their final purification and reintegrate into the divine realm.

To express their creed, the Orphics resort to a mythology of very defined themes: on the one hand, a theogony (different from the Hesiodic) and, on the other, a soteriological theory, of long later influence on the fate of the soul.

A Dionysian myth has a special relief that, in the Orphic interpretation, explains the pathetic nature of human life, in a sentence in which the soul must purge a titanic crime. According to this myth, the ancient Titans, bestial and arrogant, killed little Dionysus, son of Zeus and Persephone, luring the boy into a trap with shiny toys. They killed him, dismembered him, cooked him, and devoured him. Zeus punished them by striking them down with his lightning (only the heart of the god was saved, and from him the son of Zeus rose whole again). From the mixture of the ashes of the burned Titans and the earth, human beings later arose, harboring within them a titanic and a Dionysian component. They are born, then, loaded with something of the old guilt, and they must purify themselves in it in this life, avoiding spilling the blood of men and animals, so that, at the end of existence, the soul, freed from the body, is almost a grave and prison., can reintegrate into the divine world from which it came.

The purification process can be long and take place in several transmigrations of the soul or metempsychosis. Hence the precept of not shedding human or animal blood, since a human soul (and even that of a relative) can also beat in animal forms. Upon initiation into the mysteries, man acquires a guide to salvation, and for this reason in the Hereafter the initiates have a password that identifies them, and they know that they must present themselves before the gods beyond the grave with a friendly greeting, as indicated by the plates. orphics that are buried with them. The golden flakes point out instructions to carry out the catabasis well and enter Hades (do not drink from the fountain of Oblivion, but from the one of Memory, proclaim 'I am also an immortal being', etc.).

Orphic theogony gathers echoes of oriental theogonies and grants an essential role to divinities marginalized from the Hesiodic repertoire, such as Nix, Time and Phanes, and speaks of the primordial Cosmic Egg, or the Kingdom of Dionysus. This mythology is exposed in texts from very different periods, and is made up of very different fragments, starting with brief remains of very old poems and concluding with glosses from a late period where varied philosophical echoes are mixed. There was a tradition of ancient verse texts and prose commentators, apart from symbols and passwords. The Orphics were very fond of writings and books of various levels, some more popular proselytizing and others more refined. In the end, they come together with some magic texts.

Orphics

The Orphics (Ὀρφικοί) were a group that combined beliefs from the cult of the god Apollo with others related to reincarnation.

They believed that the soul is maintained only if its pure state is preserved. For this reason they used Dionysus as a purifying element and central figure of their beliefs.

Orpheus, for his part, with his qualities of sexual purity, his ability to prophesy what would happen after death and his musical gifts, provided another central figure for the anchoring of Orphic beliefs.

These beliefs were gleaned from sacred narratives (ἱεροί λόγοι) that are usually dated to the III century BCE. C. In V, Herodotus speaks of the Orphics and the Pythagoreans as active participants in certain taboos or prohibitions. It is also known that Plato was linked to oracles and orphic revelations. On the other hand, Aristotle knew and handled the so-called Orphic Narratives.

It can therefore be said that the denomination of orphics in the Greek world had an important position, but more in a sectarian way, and should never be confused with the Greek perception about the formation of life and of the universe.

The existence of the famous golden plates from tombs in Greece and Crete, with an Orphic character for the treatment of the soul of the dead, and prior to the Hellenistic period, only demonstrate what has been said before: the existence of some type of ritual sect with religious beliefs about the afterlife and the continuing transcendence of the soul.

Internships

The degree of institutionalization of Orphism as a religion is discussed in the research. The "minimalist" interpretation of the sources (Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff, Ivan M. Linforth, Martin L. West, and others) asserts that an Orphic religion never existed as the common belief of a cult community with corresponding rites. Therefore, one cannot speak of "Orphic" in the sense of adherence to a specific religion, but this term should only be used to designate the authors of Orphic writings. A more recent variant of the minimalist approach states that Orphism is nothing more than "the fashion of referring to Orpheus." The contrary position finds evidence in more recent findings. According to this position, Orphism is characterized, in effect, by a certain vision of the world and Orphic communities were organized which, in reference to Orpheus, jointly engaged in ritual practices that they supposed would help them to have a better existence after death. Today, it is considered plausible to assume that while there was no unified religion, there were local associations of people who shared a set of religious beliefs.

Some indications suggest that Orphism prevailed mainly among the upper classes and that the proportion of women was high.

The Pythagoreans were known for their special and strictly observed way of life, the characteristics of which included dietary rules and ethical principles in particular. Plato attests that there were Orphic rules of life as well, and mentions a past in which these rules were universally followed. Like the Pythagoreans—or at least their closest circle—the Orphic standards of conduct also included an ethically motivated vegetarianism, which was related to the doctrine of the transmigration of souls and the consequent higher estimate of the value of animal life. Food derived from the body of a dead animal was frowned upon, as were the usual animal sacrifices in Greek folk religion. Bloody sacrifices and meat consumption led to the loss of ritual purity. It is largely unknown to what extent the Orphics followed certain ethical norms beyond the general prohibition of bloodshed and whether they considered it a necessary precondition for the desired redemption. His dietary restrictions were based not only on the prohibition against killing, but also on his cosmogony; the prohibition to eat eggs, transmitted by Plutarch, was related to the mythical idea of the egg of the world. However, the egg taboo, which is only attested to late, may not have applied in the earliest times. There was no blanket ban on alcohol, at least in the early days.

It is not clear to what extent membership in an Orphic community was considered a prerequisite for following an Orphic path of salvation. In any case, ritual purification was considered an indispensable condition for the redemption of the soul. Wandering Orphics, who offered purification to everyone for payment, were probably a sign of decline in the Orphic movement.

Contenido relacionado

Minaret

Demonology

Therese of Lisieux