Ornament (music)

The ornaments or musical ornaments are flourishes that are not necessary to carry the general line of the melody (or harmony), but serve to decorate that line. These are resources that can be used in compositions in order to give them expression, ornament, variety, grace or vivacity. Many ornaments are interpreted as "sticky notes" around a leading note. The level of ornamentation in a piece of music can vary from quite ornate, which was common in the Baroque, to relatively sparse or almost non-existent.

The improvisation of ornamentation over a given melodic line was a common practice in Western classical music during the Renaissance and early Baroque periods. Improvised ornamentation continues to be part of the Irish musical tradition, characterizing Gaelic chant in particular and the entire Irish musical tradition in general.

On the other hand, ornamentation can also be precisely determined by the composer. For this, there are a series of standard ornaments that are indicated in musical notation by means of the corresponding standard symbols; while other embellishments can be added to the staff in the form of small notes or simply written in conventional size notation. Often a composer has his own vocabulary of embellishments, which is usually explained in a code-like preface.

Ornaments can be indicated by grace notes, which are notes written in a smaller size, with or without a slash through it, and are placed before or after the note they affect. Its value does not count as part of the total beat value of the measure. These notes do not have duration by themselves, but are taken from the note that precedes or follows it. Alternatively, the term may refer more generally to any of the small notes used to mark some other ornament (see appoggiatura), or in association with the indication of some other ornament (see trill), regardless of the measure used in the execution.

Ornamentation in Western Classical Music

History

In a broad sense, ornaments in music have existed since Greco-Roman times. Its use is also found in Gregorian chant and sacred music from the 11th and 12th centuries, as well as in Asian music.

Renaissance and early Baroque

At first, the incorporation of ornaments was entrusted to the interpreter, who used conventional signs and formulas. Since Silvestro Ganassi's treatise of 1535 we have instructions and examples on how Renaissance and early Baroque musicians adorned their music with improvised ornaments. A singer, when performing an aria da capo, for example, would sing the melody relatively unadorned the first time, while introducing additional embellishments the second time.

An essential function of early and Baroque ornamentation in keyboard music was to sustain notes on instruments such as the harpsichord, harpsichord, or virginale, which could not sustain a long note in the same way as a pipe organ.

In Spain the ornamented melodies in repetition were called «differences» («divisions» in England). They date back to 1538, when Luis de Narváez published his first collection of this type of music for vihuela. Until the last decade of the XVI century emphasizes divisions, which is a way of decorating a simple cadence or interval by adding a series of shorter notes. They were also known as diminutions, passaggi in Italian, gorgia ('throat', a term first used in 1555 by Nicola Vicentino to refer to vocal ornamentation), or glosas (by Ortiz, in Spanish and Italian). These types of ornaments begin as simple passing notes, progressing to gradual additions and in the most complicated cases to rapid passages of notes of equal value - virtuosity flourishing. There are standards for the design of these ornaments, to ensure that the original structure of the music remains intact. Towards the end of this period the divisions detailed in the treatises contain more dotted rhythms and other irregular rhythms as well as jumps of more than one tone.

The treatises, starting with Archilei (1589), provide a new system of expressive resources called gracias together with divisions. These have much more rhythmic interest and are full of affect as the composers turned their attention to the rendering of text. It begins with trill and cascate, and by the time we get to Francesco Rognoni (1620) we are also told about fashionable trappings like portar la voce, accento, tremolo, gruppo, esclamatione and intonatio.

The main treatises on musical ornamentation from this period are:

- Silvestro Ganassi dal Fontego Opera intitulata Fontegara...Venice, 1535

- Adrian Petit Coclico Compendium musices, Nuremberg, 1552

- Diego Ortiz Glove treaty on clauses...Rome, 1553

- Juan Bermudo The book called declaration of musical instrumentsOssuna, 1555

- Hermann Finck Pratica musica, Wittenberg, 1556

- Tomás de Sancta Maria Book called tañer fantasia, 1565

- Girolamo Dalla Casa Il vero mode diminuir...Venice, 1584

- Giovanni Bassano Ricercate, passaggi et cadentie...Venice, 1585

- Giovanni Bassano Motetti, madrigali et canzoni francesi... diminuitiVenice, 1591

- Riccardo Rognoni Passaggi per potersi essercitare nel diminuireVenice, 1592

- Lodovico Zacconi Prattica di musicaVenice, 1592

- Giovanni Luca Conforto Breve et facile maniera... a far passaggiRome 1593

- Girolamo Diruta Il transylvano, 1593

- Giovanni Battista Bovicelli Regole, passaggi di musica, madrigali e motetti passaggiatiVenice, 1594

- Aurelio Virgiliano Il Dolcimelo, MS, c.1600

- Giulio Caccini Le nuove musiche, 1602

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, Book cousin di mottetti passeggiati à una voceRome, 1612

- Francesco Rognoni Selva de varii passaggi..., 1620

- Giovanni Girolamo Kapsberger, Book secondo d'arie à una e piu vociRome, 1623

- Giovanni Battista Spadi da Faenza Book of passaggi ascendenti e descendentiVenice, 1624

Baroque

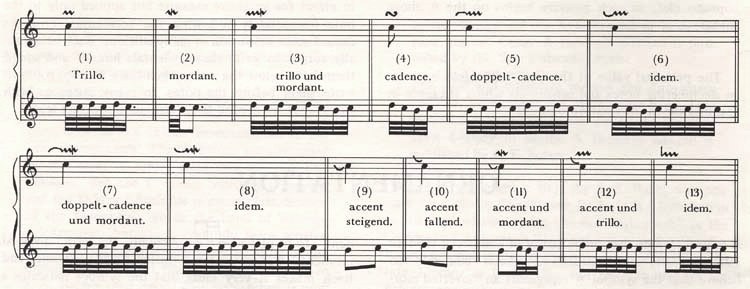

The subsequent abuse of ornaments reached such an extreme that composers were forced to specify what they wanted to be interpreted and how. Between 1650 and 1750, in the Baroque era, various treatises and explanatory tables were drawn up in which each author defined his signs (approved or not) together with the correct interpretation of him. Thus, the decorations went from being something arbitrary and at the decision of the interpreter, to being something normalized. As the Baroque advances, the ornaments acquire a different meaning. Most of the ornaments take place on the beat and make use of diatonic intervals more exclusively than the ornaments of later periods. Although any table of ornaments must provide a rigorous presentation, note duration and tempo should be taken into account, as at fast tempos it would be difficult or impossible to play all the notes that are generally required. An execution of some common baroque ornaments is set out in the following table from the Little Book of Wilhelm Friedemann Bach written by Johann Sebastian Bach.

The term agrément is used specifically to indicate the French style of Baroque ornamentation.

Classicism

Towards the middle of the XVIII century, ornamental practice is dealt with in depth in various treatises.

- For key instruments: Versuch über die wahre Art das Clavier zu spielen (Ensay on the true art of touching the key instruments) (1753) by Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach.

- For violin:

- The art of playing the violin (1751), by Francesco Geminiani.

- Versuch einer grundlichen Violinschule (1756) of Leopold Mozart.

- Regole per arrivare a saper ben suonare il violino (Rules to know how to play the violin well) by Giuseppe Tartini.

- For flute: Versuch einer Anweisung die Flöte traversiere zu spielen (1752) by Johann Joachim Quantz.

Romanticism

During the XIX century, ornamentation in music was increasingly sporadic, as were the appoggiatura that were part of the ornament they revert to ordinary included notes of the melody and bar extension, but they don't disappear completely. The use of the ornament as a melody variation technique, widely present in Classicism, gradually disappeared due to a new vision of the relationship between composer, performer and piece of music. On the other hand, other aesthetic and acoustic reasons related to the growing size of concert halls and opera houses determined the scale of all musical instruments and vocal technique towards a greater dynamic range to the detriment of agility and clarity of articulation. necessary to execute multiple ornaments.

Because of this decline in ornamental technique, his practice met with mixed success among the great composers of the 19th century. On the one hand, authors such as Paganini, Beethoven and Liszt continued to use them, while others such as Robert Schumann and Felix Mendelssohn limited themselves to sporadic use.

A special mention deserves the Polish composer Chopin, who made extensive use although strictly "personal" of the ornamentation. In his melodic writing, the ornaments acquired a meaning that had not been given until then. His waltzes, mazurkas, polonaises and works such as the nocturnes are examples of the copious use of ornaments from a completely romantic perspective.

20th century

Since the early 20th century the traditional embellishments gradually disappeared from musical writing. Although, there are a few exceptions such as some Stravinsky piano sonatas, which tried to include ornamentation by adopting the neoclassical style. In this period, musical decorations began to be the object of historical study by musicology.

Types

Trill

The trill is a musical ornament consisting of a rapid alternation between two adjacent notes, usually a semitone or tone apart, which can be identified by the context of the trill.This ornament is represented in sheet music and parts them using the letters tr, or just a t, placed above the note. Sometimes such letters tr > have been followed by a wavy line and have even been represented directly by the wavy line without the letters, especially in Baroque music and early Classicism. Throughout history various types of trills have emerged:

- Direct dial: is the one who begins and ends with the main note, except when the next note is of equal name and sound. This is the most common type currently.

- Triune invested: is the one that starts with the upper auxiliary note and ends with the main note. He was the most common in the Baroque and the principles of Classicism.

- Trine with preparation: is the one that precedes a group of notes among which there is one that is neither the main note nor the auxiliary and ends with the main note. In interpreting it, such notes should be included within the trine measure. The upward or downward preparation gives rise to the following subtypes:

- Upward Triune: if the preparation consists of two notes that ascend by joint grades to the main note.

- Triune descendant: if the preparation consists of two notes that descend by joint grades to the main note.

- Triune with resolution: is the one who ends with a group of notes among which there is one that is neither the main note nor the auxiliary. As in the previous case, such notes are included within the number of fuse required for their execution. In the Baroque there was a single type of resolution that the last alternation was not between the main note and the upper one but between the main and the lower one. In this way, the end of the trine resembles another type of musical ornament called the rumpet.

Mordent

|

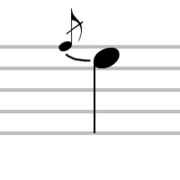

The mordent (from Latin mordere 'to bite') is a melodic ornament that generally indicates that the main or real note (the written note) should be played with a single rapid alternation of that note. note with the immediately higher or lower by joint degrees. This alternation can be made up of three, four or five notes. In any case, the notes of the mordant must be interpreted exclusively in the time previously occupied by the main note.

The two main classes of mordent are:

- Senior: implies a single rapid alternation between the main note and the top. It is represented in musical notation by an undulating line like the one used to indicate the trine, but on this shorter occasion it is placed above the note.

- Lower or invested: supposes a single rapid alternation between the main note and the bottom. It is indicated with the same scribble crossed by a vertical line.

The exact speed with which the mordant must be interpreted, as in the case of the trill, varies depending on the tempo of the piece. The precise meaning and execution of the mordant is not fixed, as it depends on both the period and the composer. Therefore, it has undergone various modifications throughout the history of music. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the execution in terms of rhythm, the initial note, the duration as well as the articulation of the music varied considerably. Most of the composers provide in the prologue of their works, a table of execution of the ornaments.

Group

The grupeto (from the Italian gruppetto, "little group") is a melodic ornament that consists of a rapid succession of a group of three or four notes that by joint degrees surround to the written note, which is considered the main note.

The groups can be differentiated according to the positioning of the notes that compose them and according to their position with respect to the note to be played.

- descending group: in which the main note is touched, the upper auxiliary note, again the main one, the lower auxiliary and again the main one.

- Grope up or invested: consisting of making the turn in the reverse sense, as in the preparation of an ascending trine. In that case, the note sequence becomes the main note, the lower auxiliary, the main one, the upper auxiliary and the main one again. The most common form of announcing it is with the same sign as the normal rumpet, but crossed by a vertical stripe and sometimes used the same rotated sign. There are also others beginning in the main note and descending a third below.

- Previous group or Step: when the sign is placed on top of the note to execute, the ridge consists of three notes whose value is taken from the beginning of the written note. That is to say, it consists of the passage of the auxiliary note superior to the lower one passing through the main note to finish again in the main note. It is an ornament close to the bite and the backrest. An example of this type of rump appears in the adagio Sonata for piano op. 2 n.o. 1 Beethoven.

- Subsequent group or ritardatto: when the sign is moved forward regarding the note to execute, that is, between two notes. Its value is taken from the end of the previous note to the rumpet. That is, the ornament is placed before the entry of the second note, but it must be interpreted in such a way that it is not hasty or hasty. It's also called long, although it remains a rapid succession of notes. Some examples can be seen in the Minueto for orchestra op. 10 n. 1 as in the Romance for violin Beethoven.

Support

The appoggiatura, (from Italian appoggiare 'to support'), is also known as long apoyatura as opposed to the short appoggiatura which is acciaccatura. This is a note that does not belong to the melody or chord. Normally it gives rise to a dissonance with respect to the predominant harmony that immediately after is resolved by joint degrees in the next weak beat. A musical appoggiatura, according to Souriau, supposes the fact of dodging the note that would be required by the structure melodic-harmonic and instead of interpreting it immediately, it is reached indirectly, even at the risk of producing dissonance. The appoggiatura, unlike the acciaccatura, is part of the melody and takes its duration from the note it precedes or the main note.

It is usually represented by one or more small notes that are drawn before or after the main note presented in conventional size. Usually, the appoggiatura will take the form of a small eighth note. It can be annotated following the procedure that we have just discussed, that is, as an ornament or by writing its execution in normal notation.

The appoggiaturas can be presented in one of the following types:

- Short support or acciaccatura: it is written with a small square cut before the main note. To expand information on this type see the article dedicated to the acciaccatura.

- Long support: is represented with a small square bracket without tachar before the main note.

- Double support: is represented with two smaller semi-cut notes before the main note that may be separated from each other by different intervals.

- Lateral support: in this case the support appears after the main note and reduces the duration of the support in its own value. It can also be simple or double.

Acciaccatura

The acciaccatura, (from the Italian acciaccare 'to crush'), also called brief apoyatura as opposed to appoggiatura, which can be designated as long or double support. It is a non-harmonic note played a whole or a semitone above or below the main note and is released immediately after.

Perhaps it is best known as a variant of the long appoggiatura, which is shorter and less melodically significant, where the delay of the main note is barely perceptible. Theoretically, almost no time is subtracted; but it does not have a specific duration or value. Therefore, it is sounded as soon as possible, taking its duration from the main note.

According to Baxter & It is customary for Baxter to do this by subtracting the value of a thirty-second note from the main note. In any case, the interruption of the acciaccatura must occur quickly, so that the actual sound(s) remain.

This sign is represented by a small note that is drawn in front of the main note presented in conventional size. The minute note is also marked with a stroke that crosses the stem obliquely. In general, the acciaccatura will take the form of a small eighth note. In Burrows' words, the acciaccatura can be interpreted in three different ways:

- interpreting it just before the pulse or time;

- interpreting it on the pulse although the emphasis is on the main note;

- interpreting it at the same time as the main note, but in staccato. This last option can only be applied in instruments that allow you to play more than one note at a time. Regardless of how acciaccatura is interpreted, its value is never counted in the total sum of compass values.

Glissando

A glissando (plural, glissandi; from the French glisser 'to slip, slide') is a sound effect consisting of rapidly moving from a sound to a higher or lower sound making all possible intermediate sounds heard depending on the characteristics of the instrument. The succession of notes can be diatonic (white or black keys on the piano), chromatic as far as possible without specific pitches. But there is also glissando in thirds, sixths, octaves, etc.

This musical ornament is represented in the score by an oblique line running from the starting note in the desired direction to the ending note. The line can be wavy or straight, more or less wide, and is often accompanied by the abbreviation “gliss”. In the notation for voice, a slur not unlike the slur was initially used, though limited to joining two adjacent notes of different pitches.

Floritura

The fioritura is also known as “cadenza”, “calderón” or “fermata”. In a musical context it is an ornament written in the manner of an improvisation, therefore the interpreter will execute it according to his own criteria. The word flourish, at first, was used to describe a type of vocal ornament, which consists of singing several notes in a row with the same vowel, which conveys the beautiful sensation of delving into a word, or at least into the soul of the interpreter..

Embroidery

The border consists of one or more notes that surround the main note by joint degrees or chromatically. It can be ascending (upper) or descending (lower) and takes place on the downbeat or part of the bar.

Arpeggio

The arpeggio consists of the more or less rapid execution of the sounds of a chord. This ornament is represented by a wavy line, or by an arc of a circle to the left of a chord. Arpeggio play normally starts with the bottom sound, unless otherwise indicated by a small curved line above the arpeggio. In piano music, when the wavy line continues without a break on the two staves of the score, the chord sounds are played one after the other, whereas when the wavy line is broken between the two staves, the staff sounds higher are played at the same time as those of the lower staff.

Ornamentation in other musical fields

Folk music

Celtic music

In Celtic music, which includes music from Ireland, Scotland and Cape Breton, ornamentation is an essential and distinctive feature. A singer, violinist, flutist, harpist, bagpiper, tin whistle player, or other instrument player can add to a given melody grace notes (called cuts on violin), slides, mordants, drones, and so on. like many other ornaments.

Urban popular music

Jazz

Jazz music incorporates a series of ornaments, which can be divided into two large groups: improvised ornaments and written ornaments. Improvised ornaments are added by performers during their solos and are often characteristic of specific instruments. The Hammond organ, when played in the jazz sub-genre, soul jazz organ trio, often features trills that outline the harmony of a chord, glides up or down on the keyboard, as well as groupet-like embellishments.. Saxophonists can decorate a simple melody line with groupets, grace notes, and short glissandi created with the mouth and reed.

Although jazz is largely based on improvisation, the style also includes music notated on sheet music, especially music for larger ensembles such as big bands. Small ensembles may also use written music for part of their performances, in arrangements of a main theme tune. Jazz sheet music incorporates most of the standard "classical" embellishments, such as trills, grace notes, and mordents. However, jazz music notation can also include other ornaments, such as the following:

- The dead notes (ad notes) or ghost notes (ghost notes): it is a percussive sound represented by an "X".

- The "doit" notes and Fall notes (fall notes): scored by curved lines above the note, indicating with the direction of the curve that the note should either be uploaded or fast down on the scale.

- Them glissandi: they are staggered slides between a start note and another destination note, represented with a long line.

- The indication fill: part of a bar with a decorative element scored with diagonal bars.

Rock and pop

Ornamentation also finds its application in urban popular music such as rock and pop. Piano playing in rock has been incorporating multiple flourishes from early 1900s blues piano styles, such as boogie-woogie. Improvised ornaments in instrumental solos or rock melody lines are often characteristic of particular instruments. Electric guitar players can choose from the huge variety of decorations that are specific to their instrument. The hammer-on and pull-off are two of the most basic techniques that can be used in the execution of classical ornaments, as well as for the execution of more particular ornaments of the guitar. For example, tapping can be introduced as a simple ornament or as a playing style in its own right.

In rock and pop, learning is often practiced "by ear," with arrangements enriched by improvisation. But the style also includes scored music, especially music arranged for large ensembles. This written music uses some of the "classical" more common as trills and mordents.

Indian Classical Music

Indian classical music is based on ragas, a modal system similar to jazz with scales of 5 to 7 principal notes (along with microtones) ascending and descending. Its origin goes back to the Vedas. Indian classical music has evolved and divided into two main blocks: North Indian Classical (Hindustani) and South Indian Classical (Carnatic).

In Indian music in general and especially in classical music, single notes or staccato are practically non-existent. With the exception of a few instruments, Indian notes (swaras) are not static in nature. Each swara is linked to its previous or subsequent note. Said extra note (or grace note), known as kan-swaras, establishes the basis of all kinds of alankars (in Sanskrit, decoration with ornaments, sound ornaments, shabd-alankar, or word ornaments). These raga embellishments, alankar is essential to the beauty of raga melodies. The term alankar appears in ancient texts. One of the earliest treatises is the Natyashastra written by the sage Bharata between 200 B.C. C. and 200 AD. Later, alankaras are described in the Sangeet Ratnakar of Sharangdev (13th century). ) and in Sangeet Parijat by Pandit Ahobal (17th century century). The classification of alankars is related to the structure and aesthetic aspect of the ragas (the last classification is shabd-alankar). All techniques refers to the production of sound used by the human voice, imitated by any type of Indian instrument (for example, sitar, sarod, shehnai, sarangi, santoor, etc.)

Variations in performance of a raga within a defined framework of compositional rules and using the different types of alankara-s can collectively be termed simply as alankar. There are different types of alankars such as Meend, Kan, Sparsh, Krintan, Andolan, Gamak, Kampit (or Kampan), Khatka (or Gitkari), Zamzama, Murki and the combination of alankars in performances of Indian classical music.

Contenido relacionado

Carnival choir

The Heart of the Toad

Loftmynd