Origins

Origen of Alexandria (c. 184-c. 253), also known as Origen Adamantius, was an early Christian scholar, ascetic, and theologian who he was born and spent the first half of his career in Alexandria. He was a prolific writer writing approximately 2,000 treatises on multiple branches of theology, including textual criticism, biblical exegesis and biblical hermeneutics, homiletics, and spirituality. He was one of the most influential figures in early Christian theology, apologetics, and asceticism. He has been described as "the greatest genius the early Church has ever produced".

Origen sought martyrdom with his father at a young age, but his mother prevented him from turning himself in to the authorities. When he was eighteen years old, Origen became a catechist at the Alexandrian Catechetical School. He devoted himself to his studies and adopted an ascetic lifestyle, as a vegetarian and teetotaler. He came into conflict with Demetrius, Bishop of Alexandria, in 231 after his friend, the Bishop of Caesarea, ordained him as a presbyter, on a journey to Athens via Palestine. Demetrius condemned Origen for insubordination and accused him of castrating himself and teaching that even Satan would eventually achieve salvation, a charge Origen vehemently denied. Origen founded the Christian School at Caesarea, where he taught logic, cosmology, history natural and theology, and was considered by the churches of Palestine and Arabia as the highest authority on all matters of theology. He was tortured for his faith during the Decian persecution in 250 and died three or four years later from his wounds.

Origen was able to produce a large body of writing due to the patronage of his close friend Ambrose, who provided him with a team of secretaries to copy his works, making him one of the most prolific writers in all of antiquity. His treatise On First Principles systematically expounded the principles of Christian theology and became the basis for later theological writings. He was also the author of Contra Celsum, the most influencer of early Christian apologetics, in which he defended Christianity against the pagan philosopher Celsus, one of its leading early critics. Origen produced the Hexapla, the first critical edition of the Hebrew Bible, which contained the original Hebrew text as well as five different Greek translations, all written in columns, side by side. He wrote hundreds of homilies covering almost the entire Bible, interpreting many passages as allegorical. Origins taught that, before the creation of the material universe, God had created the souls of all intelligent beings. These souls, at first totally dedicated to God, turned away from him and received physical bodies. Origen was the first to propose the redemptive (ransom) theory of atonement in its fully developed form and, although he was probably a subordinationist, he also contributed significantly to the development of the concept of the Trinity. Origen hoped that all people could achieve salvation, but he was always careful to maintain that this was just speculation. He defended free will and advocated Christian pacifism.

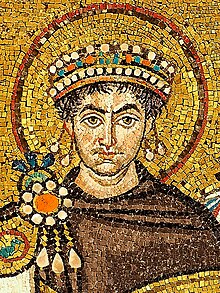

Origen is a father of the Church and is widely regarded as one of the foremost Christian theologians. His teachings were especially influential in the East, counting Athanasius of Alexandria and the three Cappadocian Fathers among his followers. most devout. The question of the orthodoxy of Origen's teachings generated the first Origenist crisis at the end of the IV century, in which was attacked by Epifanio de Salamis and Jerónimo de Estridón, but defended by Rufino de Aquilea and Juan de Jerusalén. In 543, Emperor Justinian I condemned him as a heretic and ordered all of his writings to be burned. The Second Council of Constantinople of 553 may have anathematized Origen, or may have condemned only certain heretical teachings that they claimed to derive from Origen. His teachings on the pre-existence of souls were rejected by the Church.

Life

Early Years

Most of the information about Origen's life comes from a lengthy biography of him in Book VI of the Church History, written by the Christian historian Eusebius of Caesarea. Origen as the perfect Christian scholar and as a literal saint. Eusebius, however, wrote this account almost fifty years after Origen's death and had access to few reliable sources on Origen's life, especially in his early years. Eager to obtain more material about his hero, Eusebius recorded events based on unreliable hearsay and often made speculative inferences about Origin based on the sources available to him. However, scholars can reconstruct a general impression of life. history of Origen classifying the parts of Eusebius' account that are accurate from those that are inaccurate.

Origen was born in 185 or 186 AD. in Alexandria. According to Eusebius, Origen's father was Leonidas of Alexandria, a respected professor of literature and also a devout Christian who practiced his religion openly. Joseph Wilson Trigg considers that the details in this report are not are reliable, but he claims that Origen's father was "a prosperous and thoroughly Hellenized bourgeois". According to John Anthony McGuckin, Origen's mother, whose name is unknown, may have been a member of the lower class who did not have the right of citizenship. It is likely that, due to his mother's status, Origen was not a Roman citizen. Origen's father taught him about literature and philosophy, and also about the Bible and Christian doctrine. Eusebius claims that the Origen's father had him memorize daily passages of Scripture. Trigg accepts this tradition as possibly genuine, given Origen's ability as an adult to recite long passages of Scripture at will. Eusebius also i He reports that Origen learned so much about the Holy Scriptures at a young age that his father was unable to answer his questions.

In 202, when Origen was "not yet seventeen", the Roman Emperor Septimius Severus ordered the execution of Roman citizens who openly practiced Christianity. Origen's father, Leonidas, was arrested and imprisoned. Eusebius reports that Origen wanted to turn himself in to the authorities to be executed as well, but his mother hid all his clothes and could not go to the authorities as he refused to leave the house naked. According to McGuckin, even if Origen was Had he delivered, it is unlikely he would have been punished, as the emperor only intended to execute Roman citizens. Origen's father was beheaded, and the state confiscated all the family's property, leaving it devastated. and impoverished. Origen was the eldest of nine children and, as his father's heir, took responsibility for supporting the entire family.

When he was eighteen years old, Origen was appointed catechist at the Catechetical School of Alexandria. Many scholars have assumed that Origen became the head of the school, but according to McGuckin this is highly unlikely, and more likely that he simply given a teaching position, perhaps as a "relief effort" for his destitute family. While working at school, he adopted the ascetic lifestyle of the Greek sophists. He spent all day teaching and he stayed up late at night writing treatises and commentaries. He was barefoot and possessed only a cloak. He was a teetotaler and a vegetarian, and often fasted for long periods of time. Although Eusebius does his best to portraying Origen as one of the Christian monastics of his own day, this portrayal is now generally recognized as anachronistic.

According to Eusebius, as a young man, Origen was taken in by a wealthy Gnostic woman, who was also the patron of a highly influential Gnostic theologian from Antioch, who frequently lectured at her home. Eusebius does his best to insist in that, although Origen studied while at her home, he never "prayed in common" with her or the Gnostic theologian. Origen later succeeded in converting a wealthy man named Ambrose from Valentinian Gnosticism to Orthodox Christianity. Ambrose he was so impressed by the young scholar that he gave Origen a house, a secretary, seven stenographers, a team of copyists and calligraphers, and paid for the publication of all his writings.

At some point in his early twenties, Origen sold the small library of Greek literary works he had inherited from his father for a sum that brought him a daily income of four obols. He used this money to continue his study of the Bible and philosophy. Origen studied at numerous schools in Alexandria, including the Platonic Academy of Alexandria, where he was a student of Ammonius Saccas. Eusebius states that Origen also studied under Clement of Alexandria, but according to McGuckin, this is almost certainly a hindsight assumption based on the similarity of their teachings. Origen rarely mentions Clement in his own writings, and when he does, it is usually to correct him.

Alleged self-castration

Eusebius states that, when Origen was young, after a literal reading of Matthew 19:12, in which Jesus introduces himself saying "there are eunuchs who treat themselves to they were made eunuchs for the sake of the kingdom of heaven", Origen went to a doctor and paid him to surgically remove his genitals, to ensure his reputation as a respectable tutor for young men and women. Eusebius further alleges that Origen told him in private to Demetrius, the Bishop of Alexandria, about castration and that Demetrius initially praised him for his devotion to God because of it. Origen, however, never mentions anything about castration in any of his surviving writings, and in his exegesis of this verse in his Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, written near the end of life, he strongly condemns any literal interpretation of Matthew 19:12, stating that only a fool would interpret it. the passage as a defense of the c literal astration.

Since the turn of the 20th century, some scholars have questioned the historicity of Origen's self-castration, and many they regard it as a total fabrication. Trigg claims that Eusebius's account of Origen's self-castration is certainly true because Eusebius, although he was an ardent admirer of Origen, clearly describes castration as an act of sheer madness., and would have had no reason to pass on information that might tarnish Origen's reputation unless it had been "notorious and beyond doubt". Trigg considers Origen's condemnation of the literal interpretation of Matthew 19:12 to be "the tacit repudiation of the literal reading on which he had acted in his youth".

In sharp contrast, McGuckin dismisses Eusebius' story of Origen's self-castration as "hardly credible", seeing it as a deliberate attempt by Eusebius to distract from more serious questions about the orthodoxy of Origen's teachings. McGuckin he also states: "We have no indication that the castration motive for respectability was considered standard by a teacher of mixed-gender classes." He adds that Origen's students (whom Eusebius lists by name) would have been accompanied by attendants at all times, meaning that Origen would not have had a good reason to think that anyone would inappropriately suspect him. Henry Chadwick argues that while Eusebius's story may be true, it seems unlikely, given that in Origen's exposition of Matthew 19:12, he "strongly deplored any literal interpretation of the words". Instead, Chadwick suggests: "Perhaps Eusebius was reporting his he incriticized no malicious gossip revealed by Origen's enemies, of whom there were many ». However, many notable historians, such as Peter Brown and William Placher, continue to find no reason to conclude that the story is false. Placher theorizes that, if true, it may have followed an episode in which Origen received some questioning while privately taught a woman.

Travels and early writings

In his early twenties, Origen became less interested in being a grammarian and more interested in being a rhetorical philosopher. He gave his job as a catechist to his younger colleague Heraclas. Meanwhile, Origen began to call himself a "teacher of philosophy". Origen's new position as a self-styled Christian philosopher brought him into conflict with Demetrius, the Bishop of Alexandria. Demetrius was a charismatic leader who ruled the Christian congregation of Alexandria with an iron fist, and was primarily responsible for raising the dignity of the Bishop of Alexandria; before Demetrius, the Bishop of Alexandria had been regarded simply as a priest chosen to represent his peers, but after Demetrius, the Bishop was clearly regarded as a rank superior to his fellow priests. By defining himself as an independent philosopher, Origen was reviving a role that had been prominent in pre-Christianity. he saw, but that challenged the authority of the now powerful bishop.

Meanwhile, Origen began composing his massive theological treatise On First Principles, a landmark book that systematically laid the foundations of Christian theology for centuries to come. Origen also began to travel abroad to visit schools around the Mediterranean. In 212 he traveled to Rome, which was an important center of philosophy at the time. There, Origen attended lectures by Hippolytus of Rome and was influenced by his Logos theology. In 213 or 214, the governor of Arabia sent a message to the prefect of Egypt requesting that he send Origen to meet him so that he could interview him and learn more about Christianity from his leading scholar. Origen was escorted by official bodyguards and spent a short time time in Arabia with the governor before returning to Alexandria.

In the fall of 215, the Roman Emperor Caracalla visited Alexandria. During his visit, students at the schools there protested and mocked him for murdering his brother Geta. Caracalla was outraged and ordered his troops to devastate the city, execute the governor, and kill all the protesters. He also ordered them to expel all teachers and intellectuals from the city. Origen fled Alexandria and traveled to the city of Caesarea Maritima in the Roman province of Palestine., where Bishops Theoctistus of Caesarea and Alexander of Jerusalem became his devoted admirers and asked him to deliver speeches on the Scriptures in their respective churches. This was effectively tantamount to letting Origen deliver homilies, even though he was not formally ordained. While this was an unexpected phenomenon, especially given Origen's international fame as a teacher and philosopher, it infuriated Demetrius, who regarded him as c as a direct weakening of his authority. Demetrius sent deacons from Alexandria to demand that the Palestinian hierarchs immediately return "their" catechist to Alexandria. He also issued a decree punishing Palestinians for allowing a person who was not ordained to preach. The Palestinian bishops, in turn, issued their own condemnation, accusing Demetrius of being jealous of Origen's fame and prestige.

Origen obeyed Demetrius's order and returned to Alexandria, bringing with him an ancient scroll that he had bought in Jericho containing the complete text of the Hebrew Bible. The manuscript, which had supposedly been found "in a jar", it became the source text for one of the two Hebrew columns in Origen's Hexapla. Origen studied the Old Testament in great depth; Eusebius even claims that Origen learned Hebrew. of modern scholars agree that this is implausible, but disagree about how much Origen actually knew about the language. H. Lietzmann concludes that Origen probably only knew the Hebrew alphabet and not much else; R. P. C. Hanson and G. Bardy argue that Origen had a superficial understanding of the language but not enough to have composed the complete Hexapla. A note in On First Principles mentions a "Hebrew teacher" unknown, but he was probably a consultant, not a teacher.

Origen also studied the entire New Testament, but especially the epistles of the Apostle Paul and the Gospel of John, the writings Origen considered the most important and authoritative. At Ambrose's request, Origen composed the first five books In addition to his comprehensive Commentary on the Gospel of John, he also wrote the first eight books of his Commentary on Genesis, his Commentary on Psalms 1-25 and his Commentary on Lamentations. In addition to these commentaries, Origen also wrote two books on the resurrection of Jesus and ten books of Stromata. these works contained much theological speculation, which brought Origen into further conflict with Demetrius.

Conflict with Demetrius and transfer to Caesarea

Origen repeatedly asked Demetrius to ordain him as a priest, but he continually refused. Around 231, Demetrius sent Origen on a mission to Athens. On the way, he stopped at Caesarea, where he was warmly received by Bishops Theoctistus of Caesarea and Alexander of Jerusalem, who had become his close friends during his previous stay. While visiting Caesarea, Origen asked Theoctistus to ordain him as a priest. Theoctistus gladly agreed. Upon learning of Origen's ordination, Demetrius was outraged and issued a condemnation declaring Origen's ordination by a foreign bishop an act of insubordination.

Eusebius reports that as a result of Demetrius's condemnations, Origen decided not to return to Alexandria and instead settled in Caesarea. John Anthony McGuckin, however, argues that Origen had probably already been planning to stay in Caesarea. The Palestinian bishops declared Origen to be the chief theologian of Caesarea. Firmilian, Bishop of Caesarea Mazaca (of Cappadocia), was such a devoted disciple of Origen that he begged him to travel to Cappadocia and teach there.

Demetrius raised a barrage of protests against the bishops of Palestine and the synod of the church in Rome. According to Eusebius, Demetrius published the charge that Origen had secretly castrated himself, a capital offense under Roman law at that time. and that it would have invalidated Origen's ordination, since eunuchs were forbidden to become priests. Demetrius also claimed that Origen had taught an extreme form of apokatastasis, which held that all beings (even Satan himself) would achieve salvation. This accusation probably arose from a misunderstanding of Origen's argument during a debate with the Valentinian Gnostic teacher Candide. Candide had argued in favor of predestination, declaring that the Devil was beyond salvation. Origen had responded by arguing that if the Devil is destined for eternal damnation, it was because of his actions, which were the result of his own free will. Earlier, Origen had declared that Satan was only morally disapproved, not outright disapproved.

Demetrius died in 232, less than a year after Origen's departure from Alexandria. The accusations against Origen faded with Demetrius's death, but they did not disappear entirely and continued to haunt him for the rest of his career. Origen defended himself in his Letter to Friends at Alexandria, in which he vehemently denied ever teaching that the Devil would achieve salvation and insisted that the very notion of this it was just ridiculous.

Work and teaching in Caesarea

It was like a spark that fell into the depths of our soul, setting fire, making it burst into flames within us. It was, at the same time, a love for the Holy Word, the most beautiful object of all that, which by its ineffable beauty attracts all things to itself with an irresistible force, and was also love for this man, friend and defender of the Holy Word. Therefore, he persuaded me to abandon all other goals [...] I had only one remaining object that I valued and longed for: philosophy and that divine man who was my master in philosophy. - Teodoro, Pantsa first-hand account of how it was to hear one of Origen's lectures in Cesarea. |

During his early years in Caesarea, Origen's primary task was the establishment of a Christian school; Caesarea had long been known as a center of learning for Jewish and Hellenistic philosophers, but until Origen's arrival, lacked a Christian center of higher learning. According to Eusebius, the school that Origen founded was aimed primarily at young pagans who had expressed an interest in Christianity, but were not yet ready to ask for baptism. Meanwhile, the school sought to explain Christian teachings through Middle Platonism. Origen began his curriculum by teaching his students classical Socratic reasoning. Having mastered this, he would teach them cosmology and natural history. Eventually, a Once they mastered all these subjects, he taught them theology, which was the highest of all philosophies, the accumulation of all they had previously learned.

With the establishment of the Caesarean school, Origen's reputation as a scholar and theologian reached its zenith and he became known throughout the Mediterranean world as a brilliant intellectual. they regarded Origen as the foremost expert on all matters relating to theology. While teaching in Caesarea, Origen resumed work on his Commentary on the Gospel of John, composing at least books six to ten. In the first of these books, Origen compares himself to "an Israelite who has escaped the wicked persecution of the Egyptians". Origen also wrote the treatise On Prayer, at the request of his friend Ambrosio and his "sister" Tatiana, in which he analyzes the different types of prayers described in the Bible and offers a detailed exegesis on the Lord's Prayer.

Pagans were also fascinated by Origen. The Neoplatonic philosopher Porphyry heard of Origen's fame and traveled to Caesarea to hear his lectures. Porphyry relates that Origen had extensively studied the teachings of Pythagoras, Plato, and Aristotle, but also those of important Medioplatonists, Neopythagoreans, and Stoics, including Numenius of Apamea, Cronius, Apollophanes, Longinus, Moderatus of Gades, Nicomacheus of Gerasa, Cheremon, and Cornuto. However, Porphyry accused Origen of having betrayed the true truth. philosophy by submitting his ideas to the exegesis of the Christian Scriptures. Eusebius reports that Origen was summoned from Caesarea to Antioch at the behest of Julia Avita Mamea, the mother of the Roman Emperor Alexander Severus, "to discuss Christian philosophy and doctrine with her".

In 235, about three years after Origen began teaching in Caesarea, Alexander Severus, who had been tolerant of Christians, was assassinated, and Emperor Maximinus the Thracian instigated a purge of all who had supported his predecessor. His pogroms targeted Christian leaders and, in Rome, Pontianus and Hippolytus of Rome were sent into exile. Knowing that he was in danger, Origen hid in the home of a faithful Christian woman named Juliana the Virgin, who he had been a student of the Ebionite leader Symmachus. Origen's close friend and patron Ambrose was arrested at Nicomedia, and Protoctetes, the chief priest at Caesarea, was also arrested. In his honor Origen composed his treatise Exhortation to martyrdom, now considered one of the greatest classics of Christian resistance literature. After coming out of hiding after the death of Maximinus, Origen founded a school where Gregory Thaumaturgo, more later Bishop of Pontus, was one of the students. He preached regularly on Wednesdays and Fridays, and later every day.

Later Life

Sometime between 238 and 244, Origen visited Athens, where he completed his Commentary on the Book of Ezekiel and began writing his Commentary on the Song of Songs After visiting Athens, he visited Ambrose in Nicomedia. According to Porphyry, Origen also traveled to Rome or Antioch, where he met Plotinus, the founder of Neoplatonism. Eastern Mediterranean Christians continued to revere Origen as the most orthodox of all the theologians, and when the Palestinian hierarchs learned that Beryllius (Bishop of Bostra and one of the most energetic Christian leaders of the time) had been preaching adoptionism (i.e., the belief that Jesus was born human and only made divine after his baptism), Origen was sent to convert him to orthodoxy. Origen engaged Beryllium in a public dispute, which was so successful that Beryllium promised to teach only Origen's theology from then on. In another chance, a Christian leader in Arabia named Heracleides began to teach that the soul was mortal and perished with the body. Origen refuted these teachings, arguing that the soul is immortal and can never die.

In c. 249, the plague of Cyprian broke out. In 250, the emperor Decius, believing that the plague was caused by the Christians' refusal to recognize him as divine, issued a decree for Christians to be persecuted. This time, Origen did not escape. Eusebius relates how Origen suffered "bodily torture and torment under the iron collar and in the dungeon; and he spent many days with his feet stretched out four spaces in the stocks". The governor of Caesarea gave very specific orders that Origen not be killed until he publicly renounced his faith in Christ. Origen endured two years in prison and torture, but he stubbornly refused to renounce his faith. In June 251, Decius was killed fighting the Goths at the Battle of Abritus, and Origen was released from prison. Origen's health, however, she was affected by the physical tortures inflicted on her, and died less than a year later at the age of sixty-nine. A later legend, recounted by Jerome and numerous itineraries, places her death and burial in Tyre., but little value can be attached to it.

Works

Exegetical Writings

Origen was an extremely prolific writer. According to Epiphanius of Salamis, he wrote a grand total of approximately 6,000 works in his lifetime. Most scholars agree that this estimate is probably somewhat exaggerated. According to Jerome of Strydon, Eusebius listed the titles of just under 2,000 treatises written by Origen in his lost Life of Pamphilus. Jerome compiled an abbreviated list of Origen's major treatises, detailing 800 different titles.

By far Origen's most important work on textual criticism was the Hexapla, a massive comparative study of various translations of the Old Testament in six columns: Hebrew, Hebrew in Greek characters, the Septuagint and the Greek translations of Theodotion (Jewish scholar c. AD 180), Aquila of Sinope (another Jewish scholar c. AD 117-138), and Symmachus (an Ebionite scholar c. 193-211 AD). Origen was the first Christian scholar to introduce critical markers into a biblical text. He marked the Septuagint column of the Hexapla using signs adapted from those used by textual critics. from the Great Library of Alexandria: a Septuagint passage absent in the Hebrew text would be marked with an asterisk (*) and a passage found in other Greek translations, but not in the Septuagint, would be marked with an obelus (÷).

The Hexapla was the cornerstone of the Great Library of Caesarea, which Origen founded. It was still the centerpiece of the library's collection in the time of Jerome, who records using it in his letters on multiple occasions. When Emperor Constantine the Great ordered fifty complete copies of the Bible to be transcribed and disseminated throughout the empire, Eusebius used the Hexapla as his master copy of the Old Testament. Although the original Hexapla has been lost, the text of it has survived in numerous fragments, and a more or less complete Syriac translation of the Greek column, made by the 16th-century bishop, has also survived. span style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">VII, Pablo de Tella. For some sections of Hexapla, Origen included additional columns containing other Greek translations; for the Book of Psalms, he included no fewer than eight translations is Greek, making this section known as the Enneapla. Origen also produced the Tetrapla, a smaller, abbreviated version of the Hexapla containing only the four Greek translations and not the original Hebrew text.

According to Epistle 33 of Jerome, Origen wrote extensive scolios (scolios) in the books of Exodus, Leviticus, Isaiah, Psalms 1-15, Ecclesiastes, and the Gospel of John. None of these scholia have survived intact, but parts of them were incorporated into Catenaea, a collection of excerpts from the major works of biblical commentary written by the Church fathers. Others fragments of Orogenes' scholia are preserved in Philokalia and in Pamphilus of Caesarea's Apology of Origen. The stromateis were similar in character, and the margin of Codex Athous Laura 184 contains quotations from this work on Romans 9:23 and 1 Corinthians 6:14, 7:31, 34, 9:20-21, 10:9, in addition to some other fragments. Origen composed homilies that span almost the entire Bible. There are 205 (and possibly 279) homilies of Origen extant in Greek or Latin translations.

Origen's preserved homilies are from Genesis (16), Exodus (13), Leviticus (16), Numbers (28), Joshua (26), Judges (9), 1 Samuel (2), Psalms 36-38 (9), Song of Songs (2), Isaiah (9), Jeremiah (7 in Greek, 2 in Latin, 12 in Greek and Latin), Ezekiel (14), and Luke (39). The homilies were delivered in the church at Caesarea, with the exception of the two on 1 Samuel which were delivered in Jerusalem. Nautin has argued that they were all preached in a three-year liturgical cycle sometime between 238 and 244, before the Commentary on the Song of Songs, where Origen refers to homilies on Judges, Exodus, Numbers and a work on Leviticus. In 2012, Marina Molin Pradel discovered 29 unknown homilies by Origen in a Byzantine manuscript from the 12th century from his collection. Lorenzo Perrone and other experts confirmed its authenticity. The texts of these manuscripts can be found online.

Origins is the primary source of information regarding the use of the texts that were later officially canonized as the New Testament. The information used to create the Easter Letter from the turn of the century IV, which stated the accepted Christian writings, was probably based on the lists described in the Church History (3:25 and 6:25) of Eusebius, which were mainly based on information provided by Origen. Origen readily accepted the authenticity of the epistles of 1 John, 1 Peter, and Jude, and accepted the Epistle of James as authentic with only slight hesitation. He also referred to 2 John, 3 John, and 2 Peter, but noted that he suspected all three were forgeries. Origen may also have considered other writings (rejected by later authors) as "inspired", including the Epistle of Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas and 1 Clement. "Ori Genes is not the originator of the idea of the Biblical canon, but he certainly provides the philosophical and literary interpretation foundations for the whole notion."

Existing comments

Origen's commentaries written on specific books of Scripture are much more focused on systematic exegesis than his homilies. In these writings, Origen applied the precise critical methodology that had been developed by the Mouseion scholars in Alexandria to the Christian Scriptures.. The commentaries also show Origen's impressive encyclopedic knowledge of various subjects and his ability to cross-reference specific words, listing every place a word occurs in Scripture along with all known meanings of that word; his feat is all the more impressive considering the fact that he did this at a time when Biblical concordances had not yet been compiled. Origen's gigantic Commentary on the Gospel of John, spanning over thirty and two volumes upon completion, it was written with the specific intention of not only expounding the correct interpretation of the Scriptures, but also to refute the interpretations of the Valentinian Gnostic teacher Heracleon, who had used the Gospel of John to support his argument that there really were two gods, not one. Of the original thirty-two books of the Commentary about Juan, only nine have been preserved: books I, II, VI, X, XIII, XX, XXVIII, XXXII and a fragment of the XIX.

Of the original twenty-five books of Origen's Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew, only eight have survived in the original Greek (Books 10-17), covering Matthew 13:36-22:33. An anonymous Latin translation has also survived beginning at the point corresponding to Book 12, chapter 9 of the Greek text and covering Matthew 16:13-27:66. The translation contains parts not found in the original Greek and are missing. parts found in it. The Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew was universally regarded as a classic, even after its condemnation, and eventually became the work that established the Gospel of Matthew as the first gospel. The Commentary on the Epistle to the Romans originally had fifteen books, but only small fragments have survived in the original Greek. An abridged Latin translation of ten books was produced by the monk Rufinus of Aquileia at the end of the century IV. The Constantinople historian Socrates records that Origen had included extensive discussion of the application of the title Theotokos to the Virgin Maria in his commentary, but this discussion is not found in Rufinus's translation, probably because he did not approve of Origen's position on the matter, whatever it may have been.

Origen also composed a Commentary on the Song of Songs, in which he was explicitly concerned with explaining why the Song of Songs was relevant to a Christian audience. The Commentary on the Song of Songs was Origen's most famous commentary and Jerome writes in his preface to his translation of two of Origen's homilies on the Song of Songs that "in his other works Origen habitually surpasses others. In this comment, he surpassed himself." Origen expanded on the exegesis of the Jewish Rabbi Akiva ben Yosef, interpreting the Song of Songs as a mystical allegory, in which the groom represents the Logos and the bride represents the soul of the man. believer. It was the first Christian commentary to expound such an interpretation and became extremely influential on later interpretations of the Song of Songs. Despite this, the commentary now only partially survives through a Latin translation made by Rufinus in 410.. Fragments of some other commentaries survive. The Philokalia preserves quotations from Origen, including fragments from the third book of the Commentary on Genesis. It also preserves commentaries on Psalm 1, 4:1, the small commentary on the Song of Songs, the second book of the large commentary on it, the twentieth book of the Commentary on Ezekiel, and the Commentary on Hosea. Of the non-extant comments, there is limited evidence of its readiness.

On the principles

On Principles (Greek: Περὶ ἀρχῶν [Peri arkhón]) by Origen was the first systematic exposition of Christian theology. theological principles that he develops in his work but also philosophical principles. Therefore, the principles that he proposes are the Trinity, creatures endowed with reason and the world. He composed it when he was young, between 220 and 230 AD. C., when he was still living in Alexandria. Fragments of books 3.1 and 4.1-3 of the original Greek of Origen are preserved in the Philokalia. Some smaller quotations from the original Greek are preserved in the Letter to Mennas. The vast majority of the text has only survived in a Latin translation produced by Rufinus in 397. On First Principles begins with an essay explaining the nature of theology. Book 1 describes the heavenly world and includes descriptions of the unity of God, the relationship between the three persons of the Trinity, the nature of the divine spirit, reason, and angels. Book 2 describes the world of man, including the incarnation of the Logos, the soul, free will, and eschatology. Book 3 deals with cosmology, sin, and redemption. Book 4 deals with teleology and interpretation of the Scriptures.

Against Celsus

Against Celsus (Greek: Κατὰ Κέλσου; Latin: Against Celsum), preserved entirely in Greek, was Origen's last treatise, written around 248. It is a apologetic work defending orthodox Christianity against the attacks of the pagan philosopher Celsus, considered in the ancient world to be the main opponent of early Christianity. In 178, Celsus had written a polemic entitled On the True Word, in which he had made numerous arguments against Christianity. The Church had responded by ignoring Celsus's attacks, but the work caught the attention of Ambrose, Origen's patron. Origen initially wanted to ignore Celsus and let his attacks fade, but one of Celsus's main assertions, which held that no philosopher respectful of the Platonic tradition would be stupid enough to become a Christian, prompted him to write a rebuttal.

In the book, Origen systematically refutes each of Celsus's arguments point by point and argues for a rational basis for the Christian faith. Origen draws heavily on Plato's teachings and argues that Christianity and Greek philosophy are not incompatible; and that philosophy contains much that is true and admirable, but that the Bible contains much more wisdom than anything the Greek philosophers could comprehend. Celsus' accusation that Jesus had performed his miracles using magic rather than divine powers by stating that, unlike magicians, Jesus had not performed his miracles for show, but to reform his audience.

Against Celsus became the most influential work of Christian apologetics of all; before it was written, Christianity was regarded by many as merely a popular religion for the illiterate and uneducated, but Origen raised it to a level of scholarly respectability. Eusebius admired Origen's work so much that, in his Against Hierocles 1, he noted that Against Celsus it provided a fitting rebuttal to all the criticisms the Church would ever face.

Other writings

Between 232–235, while in Caesarea, Origen wrote On Prayer, of which the full text has been preserved in the original Greek. After an introduction on the object, the necessity and the advantage of prayer, ends with an exegesis of the Lord's Prayer, concluding with comments on the position, place and attitude that should be assumed during prayer, and on the types of prayer. On the martyrdom, or Exhortation to Martyrdom, also extant in its entirety in Greek, was written some time after the start of Maximinus's persecution in the first half of 235. In this work, Origen he warns against any approach to idolatry and emphasizes the duty to suffer martyrdom with virility; while in the second part he explains the meaning of martyrdom.

Papyruses discovered at Tura in 1941 contained the Greek texts of two previously unknown works by Origen. Neither work can be precisely dated, although both were probably written after the persecution by Maximinus in 235. One is On Easter. The other is Dialogue with Heracleides, a record written by one of Origen's stenographers of a debate between Origen and the Arab bishop Heracleides, a quasi-monarchianist which taught that the Father and the Son were the same. In the dialogue, Origen uses Socratic questioning to persuade Heracleides to believe in "Logos theology", in which the Son or Logos is a separate entity from God the Father. The debate between Origen and Heracleides (and Origen's responses in particular) has been noted for its unusually cordial and respectful nature, compared to the much fiercer polemics of Tertullian or the debates of the 18th century. IV between Trinitarians and Arians.

The lost works of Origen include two books on the resurrection, written before On First Principles, and also two dialogues on the same subject dedicated to Ambrose. Eusebius had a collection of over a hundred letters from Origen and Jerome's list tells of several books of his epistles. Except for a few fragments, only three letters have survived. The first, partially preserved in Rufinus's Latin translation, is addressed to his friends in Alexandria. The second is a short letter to Gregory Thaumaturgus, preserved in the Philokalia. The third is an epistle to Sixth Julius Africanus, extant in Greek, responding to a letter sent by him (also extant), defending the authenticity of the Greek additions to the book of Daniel. Forgeries of Origen's writings made during his lifetime are discussed by Rufinus in De adulteratione librorum Origenis. The Dialogus de recta en Deum fide, the Philosophumena (attributed to Hippolytus of Rome), and Julian the Arrian's Commentary on Job are also found. have attributed to him.

Points of view

Christology

Origen writes that Jesus was "the firstborn of all creation [who] assumed a human body and soul". He strongly believed that Jesus had a human soul and hated Docetism (the teaching that Jesus had come to Earth in spirit form rather than a physical human body). Origen envisioned the human nature of Jesus as the one soul that stayed closest to God and remained perfectly faithful to Him, even when all other souls fell. In the incarnation of Jesus, his soul merged with the Logos and they "mingled" to become one. Thus, according to Origen, Christ was both human and divine, but like all human souls, human nature of Christ existed from the beginning.

Origen was the first to propose the redemptive (ransom) theory of atonement in its fully developed form, although Irenaeus of Lyons had previously proposed a prototypical form of it. According to this theory, Christ's death in the cross was a ransom to Satan in exchange for humanity's liberation. This theory holds that Satan was deceived by God because Christ was not only free from sin, but also Deity incarnate, to whom Satan had no responsibility. ability to enslave. The theory was later expanded by theologians such as Gregory of Nyssa and Rufinus of Aquileia. In the 11th century, Anselm of Canterbury criticized the ransom theory, along with the associated theory of Christus Victor, resulting in the theory's decline in Western Europe. Nonetheless, the theory has retained some of its popularity. in the Eastern Orthodox Church.

Cosmology and eschatology

One of Origen's main teachings was the doctrine of the pre-existence of souls, which held that before God created the material world, he created a host of disembodied "spiritual intelligences" (noes). All these intelligences dedicated themselves at first to the contemplation and love of their Creator, but as, by the choice of their free will, they allowed the fervor of the divine fire to cool, almost all of these intelligences finally they got bored with contemplating God, and their love for him "grew cold": hence they are called "souls" (ψυχαί) from "to cool down" (ψύχεσθαι) Those whose love for God waned the most became demons. Those whose love waned moderately became human souls, which eventually incarnated in fleshly bodies. Those whose love waned the least became angels. However, a soul that remained perfectly devoted to God became, through love, one with the Word (Logos) of God. The Logos eventually incarnated and was born of the Virgin Mary, becoming the God-man Jesus Christ.

It is not clear whether Origen believed in Plato's teaching of metempsychosis ("the transmigration of souls"; that is, reincarnation). He explicitly rejects "the false doctrine of the transmigration of souls into bodies", but this can refer only to a specific type of transmigration. Geddes MacGregor has argued that Origen must have believed in metempsychosis, because it makes sense within his eschatology and is never explicitly denied in the Bible. However, Roger E Olson dismisses the view that Origen believed in reincarnation as a New age misunderstanding of Origen's teachings. It is true that Origen rejected the Stoic notion of a cyclical universe, which was directly contrary to its eschatology.

Origen believed that, in time, the whole world would convert to Christianity, "since the world is continually in possession of more souls". He believed that the Kingdom of Heaven had not yet arrived, but that it was the duty of all Christians to make the eschatological reality of the kingdom present in their lives. Origen was a universalist, and suggested that all people could achieve salvation, but only after being purged of their sins through of "divine fire". This, of course, in line with Origen's allegorical interpretation, was not literal fire, but rather the inner anguish of knowing one's own sins. Origen also had careful to maintain that universal salvation was merely a possibility and not a definitive doctrine. Jerome cites an alleged writing by Origen which stated that "after eons and the restoration of all things, the state of Gabriel will be the same as that of the Devil, that of Paul as that of Caiaphas, that of virgins as that of prostitutes". Jerome, however, was not free from deliberately altering the quotations to make Origen seem more heretical, and Origen himself expressly points out in his Letter to Friends in Alexandria that Satan and his demons would not be included in final salvation.

Ethics

Origen was an ardent advocate of free will, and strongly rejected Valentin's idea of choice. Instead, Origen believed that even disembodied souls have the power to make their own decisions. Furthermore, in his interpretation of In the story of Jacob and Esau, Origen argues that the condition a person is born in actually depends on what their souls did in this pre-existing state. According to Origen, the superficial injustice of a person's condition at birth, with some humans poor, some rich, some sick and some healthy, is actually a by-product of what the person's soul had done in the pre-existing state. Origen advocates free will in his interpretations of instances of divine foreknowledge in Scripture, arguing that Jesus' knowledge of Judas Iscariot's future betrayal in the gospels and God's knowledge of Israel's future disobedience in the Deuteronomy story sol or show that God knew these events would happen in advance. Origen therefore concludes that the people involved in these incidents still made their decisions of their own free will.

Origen was an ardent pacifist, and in his Against Celsus he argued that the inherent pacifism of Christianity was one of the most remarkable aspects of the religion. Christians served in the Roman army, noting that most did not, and insisting that engaging in earthly wars was contrary to the way of Christ. Origen accepted that it was sometimes necessary for a non-Christian state to waged wars, but insisted that it was impossible for a Christian to fight such a war without compromising his faith, since Christ had absolutely forbidden any kind of violence. Origen explained the violence found in certain Old Testament passages as allegorical and he pointed to Old Testament passages that he interpreted as supporting nonviolence, such as Psalms 7:4-6 and Lamentations 3:27-29. Origen held that if all were peaceful and loving s like the Christians, then there would be no wars and the Empire would not need an army.

Hermeneutics

Well, who with understanding will suppose that the first, the second and the third day, and the evening and the morning, existed without sun, moon and stars? And that the first day was, so to speak, also without heaven? And who is so foolish as to suppose that God, like a husband, planted a paradise in Eden, eastward, and placed on it a tree of life, visible and palpable, that whoever tasted the fruit with his bodily teeth might gain life? And again, was he a sharer of good and evil for chewing up what was taken from the tree? And if it is said that God walks in paradise at dusk, and Adam hides under a tree, I do not suppose that no one doubts that these things figuratively indicate certain mysteries, history taking place apparent and not literally. -Origenes, On the first principles IV.16. |

Origen bases his theology on Christian Scriptures and does not appeal to Platonic teachings without first supporting his argument with a Biblical basis. He regarded the Scriptures as divinely inspired and was cautious never to contradict his own interpretation of what was written on them. However, Origen had a penchant for speculating beyond what was explicitly stated in the Bible, and this habit frequently placed him in the nebulous realm between the strict orthodoxy and heresy.

According to Origen, there are two types of biblical literature found in both the Old and New Testaments: historia ("story or narrative") and nomothesia ("legislation or ethical prescription"). Origen expressly stated that the Old and New Testaments were to be read together and according to the same rules. Origen further taught that there were three different ways in which passages of Scripture could be interpreted. The "flesh" was the literal, historical interpretation of the passage; the "soul" was the moral message behind the passage; and the "spirit" was the eternal, incorporeal reality that the passage conveyed. Origen's exegesis, the books of Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, and the Song of Songs represented perfect examples of the bodily, soulful, and spiritual components of Scripture, respectively.

Origen regarded the "spiritual" interpretation as the deeper and more important meaning of the text and taught that some passages had no literal meaning and that their meanings were purely allegorical. However, he emphasized that "passages that are historically true are much more numerous than those composed with purely spiritual meanings" and often used examples of corporeal realities. Origen noted that the accounts of Jesus' life in the four canonical gospels contain irreconcilable contradictions, but argued that these contradictions did not undermine the spiritual meanings of the passages in question. Origen's idea of a double creation was based on an allegorical interpretation of the creation story found in the first two chapters of the book of Genesis. The first creation, described in Genesis 1:26, was the creation of primitive spirits, made "in the image of God" and therefore incorporeal like Him; the second creation, described in Genesis 2:7, is when human souls are given ethereal spirit bodies and the description in Genesis 3:21 of God clothing Adam and Eve in "robes of skin" refers to the transformation of these spirit bodies into corporeal bodies. Thus, each phase represents a degradation from the original state of disembodied sanctity.

Theology

Origen's conception of God the Father is apophatic: a perfect unity, invisible and incorporeal, transcending everything material and therefore inconceivable and incomprehensible. It is equally immutable and transcends space and time. But his power is limited by his goodness, justice, and wisdom; and, though completely free from need, his goodness and omnipotence compelled him to reveal himself. This revelation, the external self-emanation of God, is expressed by Origen in various ways, the Logos being only one of many. Revelation was God's first creation (see Proverbs 8:22), in order to allow a creative mediation between God and the world; such mediation is necessary because God, as an immutable unit, could not be the source of a multitudinous creation.

The Logos is the rational creative principle that pervades the universe. The Logos acts upon all human beings through their capacity for logic and rational thought, guiding them to the truth of God's revelation. As they progress in their rational thinking, all humans become more like Christ. However, they retain their individuality and are not subsumed into Christ. Creation came into being only through the Logos, and God's closest approach to the world is the order (Fiat) to create. Although the Logos is substantially a unit, it comprises a multiplicity of concepts, so that Origen called it, in a Platonic way, "essence of essences" and "idea of ideas."

Origen contributed significantly to the development of the idea of the Trinity. He noted that the Holy Spirit was part of the Godhead and interpreted the parable of the lost coin to mean that the Holy Spirit dwells within each person and that the inspiration of the Holy Spirit was necessary for any type of speech related to God. Origen taught that the activity of the three parts of the Trinity was necessary for a person to achieve salvation. In a fragment preserved by Rufinus in In his Latin translation of Pamphilus's Apology for Origen, Origen seems to apply the word homooúsios (ὁμοούσιος; "of the same substance") to the relationship between the Father and the Son, but in other passages Origen rejected the belief that the Son and the Father were a hypostasis as heretical. According to Rowan Williams, because the words ousia and hypostasis were used synonymously in Origen's time, probably he would have rejected homooúsios as heretical. Williams claims that it is impossible to verify whether the quote using the word homooúsios actually comes from Pamphilus, let alone Origen.

Nonetheless, Origen was a subordinationist, meaning that he believed that the Father was superior to the Son and that the Son was superior to the Holy Spirit, a model based on Platonic proportions. Jerome records that Origen had written that God the Father is invisible to all beings, including the Son and the Holy Spirit, and that the Son is also invisible to the Holy Spirit. At one point, Origen suggests that the Son was created by the Father and that the Holy Spirit was created by the Son, but, at another time, he writes that "up to the present I have not been able to find any passage in Scripture indicating that the Holy Spirit is a created being". at the time Origen was alive, orthodox views on the Trinity had not yet been formulated and subordinationism was not yet considered heretical. In fact, virtually all orthodox theologians before the Arian controversy in the second half of the century IV were subordinationists to some extent. Origen's subordinationism may have developed out of his efforts to defend the unity of God against the Gnostics.

Influence on the later church

Before the crises

Origen is often regarded as the first great Christian theologian. Although his orthodoxy had been questioned in Alexandria while he was alive, Origen's torture during the Decian persecution led Bishop Dionysius of Alexandria to rehabilitate Origen's memory. Origen there, hailing him a martyr for the faith. After Origen's death, Dionysus became one of the leading proponents of Origen's theology. Every Christian theologian who came after him was influenced by his theology., either directly or indirectly. However, Origen's contributions to theology were so vast and complex that his followers frequently emphasized drastically different parts of his teachings at the expense of other parts. Dionysius emphasized Origen's subordinationist views, which led him to deny the unity of the Trinity, causing controversy throughout North Africa. At the same time, another disciple of Origen, Theognostus of Alexandria, taught that the Father and the Son were "of one substance".

For centuries after his death, Origen was regarded as the bulwark of orthodoxy, and his philosophy virtually defined Eastern Christianity. Origen was revered as one of the greatest Christian teachers; he was especially prized by scholars. monks, who saw themselves as continuing Origen's ascetic legacy. As time went on, however, Origen was criticized under the standard of orthodoxy in later times, rather than the standards of his own day. In the early IV century, the Christian writer Methodius of Olympia criticized some of Origen's more speculative arguments, but otherwise agreed with him on all other points of theology. Peter of Antioch and Eustathius of Antioch criticized Origen as a heretic.

Both orthodox and heterodox theologians claimed to follow the tradition that Origen had established. Athanasius of Alexandria, the foremost defender of the Holy Trinity at the First Council of Nicaea, was deeply influenced by Origen, and also by Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, and Gregory of Nazianzus (the so-called "Cappadocian Fathers"). At the same time, Origen profoundly influenced Arius of Alexandria and later followers of Arianism. Although the extent of his influence is disputed the relationship between the two, many orthodox Christians in ancient times believed that Origen was the true and ultimate source of the Arian heresy.

First origin crisis

The first Origenist crisis began at the end of the IV century, coinciding with the beginning of monasticism in Palestine. Stirring the controversy came from the Cypriot bishop Epiphanius of Salamis, who was determined to eradicate all heresies and refute them. Epiphanius attacked Origen in his anti-heretical treatises Ancoratus (375) and Panarion (376), compiling a list of teachings that Origen had upheld that Epiphanius considered heretical. Epiphanius's treatises portray Origen as an originally orthodox Christian who had been corrupted and made a heretic by the evils of " Greek education". Epiphanius was particularly opposed to Origen's subordinationism, his "excessive" use of allegorical hermeneutics, and his habit of proposing ideas about the Bible "speculatively, as exercises" rather than "dogmatically".

Epiphanius asked John, bishop of Jerusalem, to condemn Origen as a heretic. John refused on the grounds that a person could not be retroactively condemned as a heretic after the person had died. In 393, a monk named Atarbius petitioned to have Origen and his writings censored. Rufinus of Aquileia, a priest at the monastery on the Mount of Olives who had been ordained by John of Jerusalem and had been a longtime admirer of Origen, refused the request outright. However, Rufinus's close friend and companion, Jerome of Estridón (who had also studied Origen) agreed to the request. Around the same time, John Cassian, a Semi-Pelagian monk, introduced Origen's teachings to the West.

In 394, Epiphanius wrote to John of Jerusalem, again asking him to condemn Origen, insisting that Origen's writings denigrated human sexual reproduction, and accusing him of having been an Encratite. John again refused that request. In 395, Jerome had allied himself with the anti-Originists and pleaded with John of Jerusalem to condemn Origen, a plea John once again refused. Epiphanius launched a campaign against John, openly preaching that John was an Origenist devious. He successfully persuaded Jerome to break communion with John and ordained Jerome's brother Paulinian as priest, challenging John's authority.

Meanwhile, in 397, Rufinus published a Latin translation of Origen's On First Principles. Rufinus was convinced that Origen's original treatise had been interpolated by heretics. and that these interpolations were the source of the heterodox teachings found in it. He therefore heavily modified Origen's text, omitting and altering any parts that were not in accordance with contemporary Christian orthodoxy. In the introduction To this translation, Rufinus mentioned that Jerome had studied under Origen's disciple Blind Didymus, implying that Jerome was a follower of Origen. Jerome was so outraged by this that he decided to produce his own Latin translation of On First Principles, in which he vowed to translate every word exactly as written and expose Origen's heresies throughout the world. Jerome's translation has been lost in its entirety ality.

In 399, the Origen crisis reached Egypt. Theophilus of Alexandria, Patriarch of Alexandria, was sympathetic to Origen's supporters, and the church historian Sozomen records that he had openly preached the Origen teaching that God was incorporeal. In his Festival Letter of 399, he denounced those who believed that God had a literal, human body, calling them "simple" illiterates. A large crowd of Alexandrian monks who regarded God as anthropomorphic rioted in the streets. According to the Constantinople church historian Socrates, to avoid riots, Theophilus made a sudden turn and began denouncing Origen. In 400, Theophilus called a council in Alexandria, which condemned to Origen and all his followers as heretics for having taught that God was incorporeal, which they decreed contradicted the only true and orthodox position, which was that God had a literal physical body resembling that of a human.

Theophilus labeled Origen the "hydra of all heresies" and persuaded the Bishop of Rome Anastasius I to sign the council's letter, which mainly denounced the teachings of the Nitrian monks associated with Evagrius Ponticus. In 402, Theophilus expelled the Origenist monks from the Egyptian monasteries and banished the four monks known as the "long brothers", who were leaders of the Nitrian community. John Chrysostom, Patriarch of Constantinople, granted the long brothers asylum, a fact which Theophilus used to orchestrate John's conviction and removal from his position at the Synod of the Oak, in July 403. Once John Chrysostom had been deposed, Theophilus reestablished normal relations with the Origenist monks in Egypt and the first origin crisis came to an end.

Second originist crisis

The second origin crisis occurred in the 6th century, during the heyday of Byzantine monasticism. documented as the former, it seems that he was referring primarily to the teachings of Origen's later followers, rather than to anything Origen had actually written. Evagrius Ponticus, a disciple of Origen, had advocated contemplative, noetic, prayer. but other monastic communities prioritized asceticism in prayer, emphasizing fasting, work, and vigils. Some Origenist monks in Palestine, referred to by their enemies as "Isochristoi" (meaning "those who would assume equality with Christ"), emphasized Origen's teaching on the pre-existence of souls and held that all souls were originally equal to Christ's and would be equal again at the end of time. Another faction of Origenists in the same region insisted It was argued that Christ was the "leader of many brethren", as the first created being. This faction was more moderate and their opponents referred to them as "Protoktistoi" ("first created"). Both factions accused the other of heresy and other Christians accused both of them of heresy.

The "Protoktistoi" appealed to Emperor Justinian I to condemn the "Isochristoi" as heretics through Pelagius, the papal apocrisiary. In 543, Pelagius presented documents to Justinian, including a letter of denunciation of Origen written by Patriarch Menas of Constantinople, along with excerpts from Origen's On First Principles and various anathemas against Origen. A local synod convened to In addressing the problem, he concluded that the teachings of the "Isochristoi" were heretical and, accusing Origen as the ultimate culprit of heresy, denounced Origen himself as a heretic as well. The Emperor Justinian ordered that they be to burn all of Origen's writings. In the West, the Decretum Gelasianum, written sometime between 519 and 553, listed Origen as an author whose writings were to be categorically prohibited.

In 553, during the early days of the Second Council of Constantinople (the Fifth Ecumenical Council), when the Bishop of Rome Vigilius still refused to participate in it (despite Justinian holding him hostage), the bishops in the council ratified an open letter condemning Origen as leader of the "Isochristoi". The letter was not part of the official acts of the council and more or less repeated the edict issued by the Synod of Constantinople in 543. He cites objectionable writings attributed to Origen, but all the writings mentioned had actually been written by Evagrius Ponticus. After the council officially opened, even while Vigilius still refused to participate, Justinian presented the bishops with the problem of a text known as The Three Chapters, which attacked Antiochian Christology.

The bishops drew up a list of anathemas against the heretical teachings contained in The Three Chapters and those associated with them. In the official text of the eleventh anathema, Origen is condemned as a Christological heretic, but Origen's name does not appear at all in the Homonoia, the first draft of the anathemas issued by the imperial chancery, nor does it appear in the version of the conciliar proceedings finally signed by Vigilius, a long time later. These discrepancies may indicate that Origen's name may have been retroactively inserted into the text after the council. Some scholars believe these anathemas belong to an earlier local synod.

Even if Origen's name appeared in the original text of the anathema, the teachings attributed to Origen that are condemned in the anathema were actually the ideas of later Origenists, who had very little basis in anything Origen himself had actually written. In fact, the bishops of Rome Vigilius (537–555), Pelagius I (556–561), Pelagius II (579–590) and Gregory the Great (590–604) only knew that the fifth council was dealt specifically with The Three Chapters and did not mention origenism or universalism, nor did they write as if they knew of their condemnation, despite the fact that Gregory the Great opposed universalism.

After the anathemas

If orthodoxy was a matter of intent, no theologian could be more orthodox than Origen, no one more devoted to the cause of the Christian faith. —Henry Chadwick, scholar of early Christianity, Encyclopædia Britannica. |

As a direct result of the numerous condemnations of his work, only a small fraction of Origen's voluminous writings have survived. However, these writings still represent a large number of Greek and Latin texts, very few of which they have still been translated. Many more writings have survived in fragments through quotations from later Church fathers. It is likely that the writings containing Origen's more unusual and speculative ideas have been lost to time, making whether Origen actually held the heretical views attributed to him by the anathemas against him is almost impossible to determine. However, despite the decrees against Origen, the Church remained captivated by him and he continued to be a central figure in Origen. Christian theology throughout the first millennium. He continued to be revered as the founder of biblical exegesis, and anyone in the first millennium who took it seriously interprets it tion of the Scriptures would have had knowledge of Origen's teachings.

Jerome's Latin translations of Origen's homilies were widely read in Western Europe during the Middle Ages, and Origen's teachings greatly influenced those of the Byzantine monk Maximus of Constantinople and the Irish theologian John Scotus Erigena. Since the Renaissance, debate over Origen's orthodoxy has continued. Basil Bessarion, a Greek refugee who fled to Italy after the fall of Constantinople in 1453, produced a Latin translation of Origen's Contra Celsum, printed in 1481. The great controversy broke out in 1487, after the Italian humanist scholar Giovanni Pico della Mirandola issued a thesis arguing that "it is more reasonable to believe that Origen was innocent of what he was convicted of". Pico's position due to the anathemas against Origen, but not until after the debate had received considerable attention.

The most prominent defender of Origen during the Renaissance was the Dutch humanist scholar Erasmus of Rotterdam, who considered Origen the greatest of all Christian authors and in a letter to Johann Eck wrote that he learned more about Christian philosophy in a single page from Origen than ten pages from Augustine. Erasmus particularly admired Origen for his lack of rhetorical flourishes so common in the writings of other patristic authors. He borrowed much from his defense of free will expressed in On First Principles in his 1524 treatise On Free Will, now considered his most important theological work. In 1527, Erasmus translated and published the surviving Greek portion of Commentary on the Gospel of Matthew by Origen, and in 1536 he published the most complete edition of Origen's writings printed up to that time.

While Origen's emphasis on the human effort to achieve salvation appealed to Renaissance humanists, it made him far less attractive to Reformation advocates. Martin Luther deplored Origen's understanding of salvation as hopelessly flawed and stated that "in all of Origen there is not a single word about Christ". He accordingly ordered that Origen's writings be banned. However, the earlier Czech reformer Jan Hus had been inspired by Origen for his view of that the Church is a spiritual reality rather than an official hierarchy, and Luther's contemporary, the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli, drew inspiration from Origen for his interpretation of the Eucharist as symbolic.

In the 17th century, the English Platonist Henry More was a devout Origenist, and although he rejected the notion of salvation universal, he accepted most of Origen's other teachings. Benedict XVI expressed admiration for Origen, describing him in a sermon as part of a series on the fathers of the Church as "a crucial figure for the integral development of Christian thought"., "a true teacher", and "not only a brilliant theologian but also an exemplary witness of the doctrine he transmitted". He concluded his sermon by inviting his audience to "receive in their hearts the teaching of this great teacher of the faith." Modern evangelical Protestants admire Origen for his passionate devotion to the Scriptures, but are often puzzled or even horrified by his allegorical interpretation of the Scriptures, an interpretation that many consider to ignore the literal and historical to behind them.

Translations

- Translations to the Spanish works of Origen

- Against Celsius. Introduction, version and notes by D. Ruiz Bueno (BAC 271) Madrid 1967.

- Call to martyrdom. About prayer. Introduction, translation and notes by T. Martin, Salamanca 1991.

- Commentary on the Song of Songs. Introduction and notes by M. Simonetti. Trad. de A. Velasco Delgado (BPa 1) Madrid 1994.

- Homilies on the Exodus. Introduction and notes by M.I. Danieli. Trad. de Á. Castaño Félix (BPa 17) Madrid 1992.

- Treaty on Prayer. Translation, presentation and notes by F. Mendoza, Madrid 1994.

- Homilies on Genesis. Introduction, translation and notes by J.R. Díaz Sánchez‐Cid (BPa 48) Madrid 1999.

- Homilies on the Song of Songs. Introduction, translation and notes by S. Fernández (BPa 51) Madrid 2000.

- Homilies on Jeremiah. Introduction, translation and notes by J.R. Díaz Sánchez‐Cid (BPa 72) Madrid 2007.

- Homilies on the Numbers. Introduction, translation and notes by J. Fernández Lago (BPa 87) Madrid 2011.

- Homilies on Isaiah. Introduction, translation and notes by S. Fernández (BPa 89) Madrid 2012.

- Homilies on the Gospel of Lukeprepared by A. López Kindler (BPa 97) Madrid 2014.

- On principles. Introduction, critical text, translation and notes by S. Fernández (Source Patristics 27), Madrid 2015.

About Origins

- Hubert Jedin, Church History ManualVol I, cap XIX. ISBN 84-254-0205-0

- Henri Crouzel, Origins, BAC, Madrid 1998.

- Enrique Moliné Coll (1995). The Fathers of the Church: An introductory guide. Editions Word. pp. 151 et seq. ISBN 9788498401714.

- Bastitta Harriet, Francisco (2012). « Platonic tradition about the principles in Origen of Alexandria» (pdf). Diania (Mexico) LVII (68): 141-164. ISSN 1870-4913. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Consultation on 3 July 2014. site

Contenido relacionado

Bloemfontein

Sergius III

The birth of Venus (Botticelli)