One thousand days

The War of the Thousand Days was a civil conflict of Colombia disputed between October 17, 1899 and November 21, 1902, for nonconformities against policies and previous results of the policy of the policy of the policy of the Regeneration supported by the National Party (Movement initially headed by Rafael Núñez formed by moderate conservatives and liberals). Many radical and conservative liberal politicians rejected measures that considered exaggerated by the government, in addition the radicals of the Liberal Party sought ways to reach the government and reverse the changes of regeneration, but the nationalists who had control of the government in their hands had strategies in their favor that could restrict the actions of other politicians and parties and move them away from it.

During the century XIX </s War of 1830, War of the Supreme, the civil war of 1851, that of 1854, 1860, 1876-1877, 1884-1885, 1895 and the War of the Thousand Days ; several regional (for some authors 54), with various connotations: hegemonic, focused on the struggle for power; Likewise, there was an internal struggle between the liberal and conservative parties, on the other hand, those of a civil nature, based on the defense of a political interest. In the case of the War of the Thousand Days, Miguel Antonio Caro, leader of the National Party, expresses an interest in perpetuating himself in power, a situation that causes a discontent that adds to social discomfort both in the elites and in the popular sectors.

The abrupt change caused by the repeal of the Rionegro Constitution of 1863 (which reinforced the federal model) by the constitution central of 1886 (established under the mandate of Rafael Núñez), in addition to the violent attempts for co -optation of conservatives Historic through Moroccan, such as the liberal interests of retaking power, were the main causes of war.

The Government of the National Party at the head of President Manuel Antonio Sanclemente, who was overthrown on July 31, 1900 by José Manuel Marroquín Ricaurte, representative of the Conservative Party, in alliance with the Liberal Aquileo Parra; since then, thereafter, from then on, And despite this alliance, the war would continue between liberals and conservatives historical . This war was characterized by an irregular confrontation between the well -organized government army and a poorly trained and anarchic liberal army.

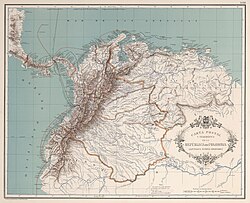

It was an international conflict that partially extended to neighboring countries such as Ecuador and Venezuela, in which battles between Colombian, Ecuadorian and/or Venezuelan forces that supported Colombian actors in conflict were fought. Other nations such as Guatemala, El Salvador and Nicaragua supported the liberals and conservatives with armament and supplies. The United States also intervened in war actions in Panama, where an American fleet, the uss Nashville (PG-7) guaranteed the security of the Isthmus from the Mallarino-Bidlack treaty of 1846.

The conflict resulted in the economic devastation of the nation, more than one hundred thousand dead, the disappearance of the National Party and the state in which the country remained after the conflict, the social consequences that soon gave rise to the subsequent separation of Panama (which at that time was one of the departments of Colombia) in November 1903.

For the number of casualties and size of the forces, it is usually considered the largest civil war in Colombia, not including violence of the middle of the century XX and the subsequent internal conflict, which are not considered civil wars itself.

Background

In the century XIX </s Civil Wars, initially between Bolivarian and Santander, centralists and federalists, slaves and abolitionists, confessional and secular, among others, which eventually evolved into conflicts between conservatives and liberals.

The constitution of Rionegro of 1863, which created the Federal State (United States of Colombia) established by the radical liberals led by Tomás Cipriano de Mosquera after his victory in the civil war of 1860-1862, he increasingly sowed anticlericalism more and more, free market and local distinctions, as among the same states that sometimes had much larger armies than those of the central government and had the right to declare war between them, reduced the presidential period two years and endowed greater power to the Parliament that to the President. In a situation dotted with social conflicts and civil wars, the independent liberals together with the conservatives resumed power in the war of 1884-1885 and the 1886 Constitution that sought, unlike the previous Constitution, a strong centralist state, a strong centralist state, was written, a strong centralist state, Catholic and protectionist confessional, in a process that was known as regeneration, led by Rafael Núñez and Miguel Antonio Caro.

With the 1886 Constitution, the concordat was also given with the Holy See, through which education in Colombia was under the control of the Catholic Church, which determined the school and university texts that could be studied by establishing censorship for reasons for reasons religious or political. Likewise, all the appointment of teachers were under their supervision, unleashing in the educational centers of the country the persecution and expulsion of the educators who did not act under the Catholic will. Liberal public employees were fired and as Lucas Caballero recounts in their memoirs, journalists and critics of hegemonic governments, such as Ospina and Santiago Pérez, they were imprisoned or condemned to exile; However, the opposition of others such as Rafael Uribe Uribe and Marceliano Vélez was allowed.

The liberals made an attempt to insurrection in 1895, and the exaltation and conflicts of the moment generated quarrels between the opposition candidates and those of the official government. The opposition businessmen and merchants of the governments on duty were harassed and their activities were hindered. Finishing the century XIX , in the Colombia Congress there was only one liberal congressman. /i>]

On the eve of the war, the country was divided into several political currents: among the conservatives were the nationalists, who formed the government and were characterized by being highly exclusive with the liberals, and the conservatives historical , which accepted the need to understand the liberals, which at that time were an important political group, also opposed the press censorship and the restriction of individual rights, as the nationalists protected in a transitory passage in a transitory passage of The Constitution of 1886.

The liberals were also fractionated: those who wanted to exhaust the political instances to access (pacifists) led by Aquileo Parra, and those who were willing to conquer the spaces that the government has closed them for fourteen years through the armed confrontation (Belicists) led by Rafael Uribe Uribe.

Causes

Disient conservatives formally departed from the National Party in January 1896 with the publication of a manifesto entitled " reasons for the dissent ". Drafted by Carlos Martínez Silva of the department of Santander, a document signed by twenty -one promiting conservatives (all former collaborators of the regeneration, movement initially led by Rafael Núñez, made up of moderate and conservative liberals), a document that later obtained the support of Marceliano Vélez, leader of an important block of conservative dissidents of the department of Antioquia. The document was an accusation of practically all aspects of regeneration and, at the same time, a declaration of the historical principles of the Conservative Party. Dissidents recognized the great achievements of regeneration: the achievement of the National Unity and the definition of the Church issue. But they claimed that the Constitution of 1886 and the economic and political formulas of the governments that followed them had constituted an exaggerated reaction against the extreme federalism and the weakness of national governments under the Constitution of 1863. The policy and administration proposed by regeneration He had returned authoritarian and his fiscal policies had been disastrous. ”

The 1898 presidential election followed a campaign tossed by the winds of war. Since March 1897, on behalf of the liberals, Nicolás Esguerra had proposed a national front, with a plural executive of historical liberals and conservatives that excluded nationalists (followers of the National Party) from the government. For its part, the conservative party he was continually opposed to everything that the nationalist government could represent.

Sanclemente, due to health problems, had to provisionally delegate power to Vice President José Manuel Marroquín, this was taken advantage of by the historical conservatives since Marroquín was close to this side. Marroquín's first acts of government, in economic matter, surprised everyone: the liberals applauded him and the nationalists felt disappointed. Marroquín had begun to dismantle the protectionist policy of the Regeneration and give way to free trade. Miguel Antonio Caro sent urgent messages to Sanclemente asking him to come and take office, creating a power vacuum that allowed the conditions for war to arise. Sanclemente assumed power in the first days of November 1898, thus ending the eighty days of the Moroccan administration.

Vice President Marroquín resigned harassed by Caro's criticisms on September 20, the Senate rejected the resignation while Liberals announced their support for free trade reforms, which were presented by Marroquín in the Senate on September 26, 1898.

On October 6, 1898, the Senate refused to approve the election law, which liberal followers of Rafael Uribe Uribe considered a necessary guarantee for suffrage, which was one of the main political causes of the conflict. From that event, Uribe Uribe's liberals concluded that by going to the polls they would never have access to power. From that moment on, the Liberals divided into pacifists or directorists, led by the head of the Liberal Directorate, Aquileo Parra; and warmongers, who followed Rafael Uribe Uribe.

The political reforms in favor of free trade that the historians and liberals had been promoting were opposed to the nationalist postulates of the Regeneration, so no agreement could be reached between the groups. In turn, regarding the conception of the State, the conservative and liberal postulates were opposed to those of the National Party.

The board of delegates of the conservative party on August 17, 1899 declared in its agreement number 30:

"1. At present there is no political link between the government, which is nationalist and the Conservative Party; and that, on the contrary, the members of this community are systematically removed from the public thing"...

concluded in the same document, among its agreements:

"1. Declaring that the current Government, for its policy and trends, does not correspond to the ideals, practices and aspirations of the Conservative Party"...

The war began between November 11 and 13, 1899 with the assault on Bucaramanga by poorly organized liberals, provoking a response from the central government.

The war

During the first phase of the conflict, both sides fought with armies in large pitched battles, their commanders being called the Gentlemen Generals for the respectful treatment that the victors gave to the defeated. Initially this was due to to the distrust of the high liberal commands to their own guerrillas, considered bandits and anarchic. The same rebel military command was divided by internal rivalries, between generals Justo Leónidas Durán, Benjamín Herrera and Rafael Uribe Uribe whose attempt to unite and coordinate through the appointment of Gabriel Vargas Santos as Provisional President of the Republic it was a failure.

The insurgents received the support of liberals from other countries, especially the government of Venezuela. It should be mentioned that the conflict degenerated into a long guerrilla war in which both sides indulged in excesses and brutalities on a scale never seen in Colombia.

On the other hand, the historical conservatives grouped in the conservative party conspired against Sanclemente. The top leaders of the party and of that current, Marceliano Vélez and Carlos Martínez Silva, wrote letters in which they urged the conservatives not to support the government.

First phase

The rebellion in Santander

On October 17, 1899, the Liberals rose up in various parts of the country, immediately beginning to take towns and cities due to the lack of reaction from the government, which was taken by surprise. That day, General Juan Francisco Gómez Pinzón declared himself in favor of the war on his La Peña hacienda, took the town of El Socorro and on the way to San Gil defeated the government troops under the command of Captain Sanmiguel. The next day and at night the colonel Juan Francisco Garay started the liberal uprising from the Las Llanadas neighborhood, without any resistance from the local authorities, who fled to the town of La Cruz (today Ábrego). Colonel Garay managed to later take the town of Río de Oro, very close to Ocaña, and went to La Cruz to protect the advance of General Justo Durán who came from Cáchira to assume command of the liberal forces of Magdalena and north of Santander. When he arrived, he found that the historical conservatives had signed a pact with the liberal chief Adán Franco, in which they censured the Sanclemente government.. For this reason, the government declared martial law for the entire day of October 18.

The first military defeats for the Liberal side began days after the war began at the Battle of Los Obispos on the Magdalena River on October 24, when Santander rebels attempted to establish contact with the coast via that river. As a result, the rebel fleet was destroyed and General Durán, who planned to start operations on the banks of the Magdalena, had to limit himself to making tours of the territory to incorporate survivors to his cause, and after having supplied himself, he left with the Cazadores, Libres battalions de Ocaña, Carmen de Santander, Córdoba and La Palma to fight the battles of Peralonso (December 15 and 16 of that year), Cáchira and Arboledas, among others.

The Liberals were isolated after the defeat in the Battle of the Bishops, making it impossible for them to support General Vicente Carrera in Tolima, who was defeated and died in San Luis on November 14, from then the Tolimense liberal forces were reduced to guerrilla actions. Despite this setback, the liberal forces in Santander passed 7,000 men by the end of that month.

The rebellion in Cauca

At the end of October 1899, liberal guerrillas also broke out in the department of Cauca, taking Tumaco and assaulting Palmira in November, but were defeated. The rebel victory in Peralonso gave them new life and they began to recruit men in the indigenous communities of Cauca, and many liberals exiled in Ecuador also returned. There was a rebel attack against Popayán on December 25, being defeated twenty kilometers south of the city, in Flautas. Many fled to Ecuador again, where the liberal president, Eloy Alfaro, armed the rebels, who returned to the attack, leading to a battle near the border, at the site of Cascajal (located in the municipality of San Lorenzo, department of Nariño), on January 23, 1900. The government victory was complete and with it the rebellion in Cauca ended momentarily.

The economic aid granted by the then bishop of Pasto, Fray Ezequiel Moreno y Díaz, to the conservative forces was crucial for the government victory in the territory of the current department of Nariño, also supporting the Ecuadorian conservatives opposed to Alfaro.

The rebellion in Panama

Despite this, the liberals, encouraged by their victory in Peralonso, decided to launch a surprise offensive in Panama where they were very successful due to the distance of this department from the capital. The assault was led by liberals exiled in America Central, especially Nicaragua, where its president José Santos Zelaya gave them significant support. Finally, the exiles, led by Belisario Porras Barahona, left on March 31, 1900 from Punta Burica in a ship loaded with weapons and supplies. They landed near David on April 4, where they defeated the small local garrison, joining their leaders with their men in their immediate march to Panama City. Porras, after receiving Zelaya's help, appointed exiled caudillo Emiliano Herrera, a native of the department of Boyacá, as commander of his army. The rebels made the mistake of not accelerating their march when they could and reinforcements under the command of General Víctor Salazar arrived at the poorly defended departmental capital, which began to be fortified. It was commanded by the governor of the department, General Carlos Albán.

However, Albán, eager to engage in combat as soon as possible, did not wait for the defenses to be ready and sent three battalions to Capira to stop the rebels. The combat took place on June 8 and in a first encounter the liberals were defeated; Forced to retreat, the government army pursued them, which was used to lure the government into difficult terrain where the liberals counterattacked and completely defeated their enemies, who fell back to the departmental capital.

The Liberals advanced to La Chorrera, where they established their base of operations; His plan was to attack the Calidonia bridge, forcing the enemy to concentrate in that place, where the rebels could choose and attack the weakest points. However, Herrera decided to attack the bridge with only his men without waiting for Porras's reinforcements so as not to have to share the glory with him.

Herrera advanced and took positions on July 20 at a railway station in Corozal, the next day Governor Albán arrived with three battalions, and an important battle ensued in which the government forces were once again defeated and forced to return to the city of Panama. Herrera took the opportunity to immediately start negotiations on his behalf to obtain the capitulation of the city. After this, panic spread in the city, it was feared that it would be looted and destroyed in the fighting, but then General Salazar convinced his superior, Albán, that he should not surrender and his only option was to resist.

Government patrols detected the rebels approaching by land and by sea in boats. Aware of the upcoming assault, Salazar fortified several buildings and roads, but seeing how vulnerable the position of the Calidonia bridge was, he understood that defending it was a waste and decided to do it with few men while larger forces were hidden in the surroundings waiting to ambush the enemy.. When Porras arrived at the place, Herrera again challenged him and against his orders attacked the fortified positions, resulting in a massacre (July 24). Subsequently, a night attack of his was detected prematurely and ended in a new failure.

The following day a ceasefire was held in which both sides collected their dead and wounded, suspended at 4:00 p.m. when Herrera resumed his attacks, which again ended in butchery for his men. The attacks ended when news arrived of the arrival of government reinforcements from Colón; Sporadic shooting ensued until the next day when his forces retreated into the interior of the Azuero peninsula, hiding in the jungle. Meanwhile, Governor Albán managed in a short time to reestablish his control throughout the department.

Offensive in Santander

As the war progressed, it took a more repressive and cruel turn. Even the population divided to take part in each side in a more fanatical way, despite the efforts of each party to obtain victories that would later be illusory. In Santander the liberals reorganized and decided to take the strategic cities of Cúcuta and Bucaramanga; General Herrera attacked the first with a large army and the commander of the government troops in the plaza, General Juan B. Tovar, evacuated it with his troops and went to reinforce the defenses of the second city. The remaining troops in Cúcuta, under the command of Colonel Luis Morales Berti (five hundred well-armed men) surrendered on November 1, 1899, the city became their main base of operations. There the liberals managed to gather, according to them themselves, some 8,000 to 10,000 well-armed men (plus 1,500 to 2,000 llaneros that Vargas Santos managed to gather) to face the safe government offensive that would have 8,500 soldiers in Boyacá ready to attack. Liberal forces are currently being rejected, estimating the number of uprisings at 3,500, many of them armed only with machetes; on the other hand, the government forces that marched against them numbered 10,000. Uribe Uribe's men, meanwhile, attacked Bucaramanga on November 11, the city was defended by General Vicente Villamizar, who was successful and, after two days of fierce battle, he forced the enemy to retreat. Uribe Uribe joined Durán and with some 2,000 men marched to join Herrera, beginning an important offensive into the interior of the country. However, this defeat cost him the title of Commander in Chief of the liberal forces, a rank that he received on the 12th of the same month, since moreover he withdrew from the battlefield when the soldiers from him they kept attacking.

In the battle of Peralonso, Uribe Uribe managed to defeat Villamizar and cross the Peralonso river, being able to take Pamplona on the 24th, joining the liberal troops with General Vargas Santos and a column of llaneros on the following day; Vargas was named Provisional President of the Republic to unify the liberal command. Vargas was a combatant and veteran leader of several rebellions, caudillo of Casanare and was enthusiastically received by the desperate liberal forces, who numbered more than 12,000 men according to them. Unfortunately, and despite his prestige as leader of the previous liberal rebellion, he lacked military talent, he also tried to demobilize the troops of Uribe Uribe who was a powerful rival of his and tried to alienate him politically by contributing with that alone to divide their forces. The liberals ended up giving more importance to the fight between Vargas Santos and Herrera against Uribe Uribe than to the common fight against the nationalist government. Given this, Uribe Uribe decided to continue the march taking advantage of the fact that the government was distracted by the uprising in Antioquia del January 1, 1900, besieging the city until its surrender. At this time, more than 5,000 men were advancing with Uribe Uribe while more than 6,000 remained in reserve garrisoning Cúcuta (the actual numbers were probably more modest). The events in Panama and Cauca showed the Colombian government that the generalized insurrection throughout the country had failed and it was possible to put an end to the raised foci one by one after managing to isolate them. President Sanclemente prepared an offensive against the main stronghold in Santander, replacing Villamizar with General Manuel Casabianca, who was determined to stop the rebel advance against Bogotá. Taking advantage of the inaction of the liberals located near Cúcuta, Casabianca was able to gather his forces (about 9,000 men) while General José María Domínguez advanced towards the city from Ocaña. Casabianca warned the government that Domínguez's column could be easily isolated and destroyed by the Liberals but he was not listened to.

Seeing the danger that this joint offensive meant for his forces, Vargas Santos, who was planning after Peralonso how to continue the campaign, ordered Uribe Uribe and Herrera to finish off Domínguez. Uribe Uribe quickly marched to try to prevent both government forces from meeting, since Casabianca was quickly marching to help Domínguez. Both generals hoped to meet in Pamplona. Meanwhile, Herrera took the opportunity to attack and defeat Domínguez in Gramalote (February 2), the remains of the government army fled to the nearby Terán hacienda, but Herrera dedicated himself to celebrating and did not pursue them. He finally took the opportunity to send some troops that pretended to be government reinforcements and managed to capture Domínguez, who came out to receive them. Aware of this, most of his troops capitulated and only a few returned to Ocaña. Terán's victory gave Uribe Uribe's troops enormous booty, including more than two thousand rifles. Fearing that he would be replaced by his subordinate, Vargas Santos ordered his troops to retreat to Peralonso, wasting the opportunity to advance against the government at its weakest moment.

The rebellion in Tolima

The department of Tolima was the place of operations of the guerrillas Ramón "El Negro" Marín, a native of Marmato, and Tulio Varón. The forces of both assaulted the town of Honda in January 1900, where they seized the ammunition and rifles stored in the barracks, and also kidnapped the Spanish ambassador Manuel Guirior, who was released after paying 100 gold pesos.; then they continued their advance towards La Dorada. Continuing with their campaign against the conservatives, in November of that year the joint guerrilla forces of Marín, Varón, Aristóbulo Ibáñez, Juan MacAllister and Avelino Rosas attacked the government forces under the command of Nicolás Perdomo in Girardot in order to seize supplies and weapons from Europe, but after a day of fighting they were repulsed.

In April 1901 the Pagola battalion was attacked by Tulio Varón's guerrillas while camping on their way from Antioquia, leaving only twenty surviving soldiers. Varón continued with his nocturnal incursions into army camps, and that is how, at dawn on August 31, his forces surprised the army stationed at the La Rusia hacienda, north of Tolima, killing more than five hundred soldiers with knives. On September 21, Tulio Varón had the misfortune of assaulting Ibagué in a drunken state, along with his troops, falling dead from a shot. After that, his corpse was dragged to the house where his wife lived.

Second uprising in Cauca

The liberal success in the Terán hacienda (Santander) motivated a new uprising in Cauca; With the support of Ecuadorian President Eloy Alfaro, the exiled Colombians launched a new offensive. However, the nationalist forces were strong in the region due to the support of the Catholic Church, led by Bishop Ezequiel Moreno, who mobilized the population in the face of a possible Ecuadorian invasion, a holy war against that government, known for its secularist laws. In March, the exiles invaded Cauca recruiting troops from some indigenous communities. The government response was immediate and sent a powerful contingent of well-armed regulars. On the 27th of the same month, the Liberals, supported by Ecuadorian battalions, tried to take Ipiales; After three days of resistance, the arrival of government reinforcements and exiled Ecuadorian conservatives forced the rebels to retreat. The defeated decided to take refuge in Ecuador, since their troops also included a large number of children, women and the elderly, many wounded. The Liberals launched a second attack and took Flautas on April 16, where they gathered their forces (thousands of Liberals and allied Indians); Taking advantage of this concentration, government forces surrounded the town and attacked the same day. However, most of the rebels managed to escape but were left without support or supplies and with low morale.

It was then that Moreno insisted on launching an attack on Ecuador and trying to overthrow Alfaro. On May 22, Colombian troops and Ecuadorian exiles crossed the border and attacked the town of Tulcán, but were repulsed. Thus the war fell into a stalemate, if either side invaded the other's territory, it was quickly repulsed. Alfaro pledged to support the Liberals but made it clear to his leadership that they were not willing to go to a full-scale war with Colombia. The Liberals launched one last offensive on July 20, crossing near Ipiales, being surprised by government troops and being expelled. The rebels were defeated in Cauca, but surprisingly they were helped by their fellow insurgents in Tolima, they crossed the Cordillera de the Andes and invaded Cauca from the north in October, managing to gain some support from the population, forming a column of 2,000 men with whom they attacked the capital of said department, Popayán. The government was taken by surprise and could not initially stop the insurgents, only the timely arrival of reinforcements allowed the government to defeat the liberals a few kilometers from the city. The liberals, always short of ammunition, quickly depleted their reserves and dispersed, pursued by their enemies. The conservative repression was not long in coming, the Cauca rebels, especially indigenous people, were summarily shot, while the Tolimenses escaped to their region. The indigenous communities were harshly punished so that they would not rise up again and the families and close friends of the liberal leaders were imprisoned. An important group of liberals went into exile in Ecuador, waiting for the result of the war in Santander to return or not to the offensive.

Battle of Palonegro

In February 1900 the Liberals were isolated in Santander and with very slim chances of victory. In addition, the human resources of said department were depleting while the ranks of the army replaced the casualties and remained intact; despite the enthusiasm of his volunteers, the rebels were running out of supplies, depending on what they could take from their enemies.

The remaining liberal forces in other parts of the country awaited the next action by Vargas Santos to see what to do, but he refused to take the offensive given the vulnerability of his forces, so the war remained inactive for several months. To worsen the result. when Vargas Santos finally began mobilizing his army in late April, he didn't even have a definite plan. He advanced south from Cúcuta after a malaria epidemic broke out. However, he did not act against the enemy troops that remained in Pamplona, assuming that they would not move. The latter saw how his commander, General Casabianca, was appointed Minister of War and was replaced by General Próspero Pinzón, a devout Catholic who managed to implant in his troops the idea of fighting a holy war. Unknowingly, both sides were marching at the same time in search of a decisive battle. The movements of the Liberals were quickly detected by their enemies and the Nationalist government insisted General Pinzón start an offensive towards Bucaramanga, while the Liberals continued south. passing through Rionegro and arriving on May 10 at Palonegro, where they decided to stop the enemy. The next day the most important battle of the entire war began, about 7,000 liberals faced about 18,000 nationalists. On the 25th the fighting ended with the total defeat of the liberals, who since then abandoned regular warfare tactics, Pinzón, however, decided not to pursue them, for which he was criticized.

End of the rebellion in Santander

Some 3,400 surviving Liberals arrived in Rionegro and their commanders engaged in heated discussions on what to do between the 26th and 27th of the same month. When General Pinzón learned of the rebel plan to enter the jungles of the northwest of said department, he gave up the pursuit, certain that they would not be able to survive the harsh jungle living conditions. Instead, he decided to attack Cúcuta to cut off any possible support from Venezuela to the liberals. However, Vargas Santos understood that it was impossible for him to defend Cúcuta and entered the jungle at the head of the liberal column near Ocaña, where in two weeks due Due to the terrible conditions, more than a thousand men died, disappeared or deserted. He also sent a letter to Pinzón asking him to release Cúcuta from his siege.

Knowing that Bucaramanga was defenseless with most of the rival troops in Cúcuta, Vargas Santos decided to attack it, but the route was too inhospitable, they passed near Rionegro and finally at the beginning of August less than 1500 men arrived with a few hundred women while Pinzón captured Cúcuta on July 16 where he learned of the enemy movements, returning to Bucaramanga on the 27th and finding the liberal column on August 3 and forced them to flee to the west.

Vargas Santos decided to march to the outskirts of Bogotá with the less than a thousand men he had left, but Pinzón anticipated him and found him when he was crossing the Sogamoso River, the liberals had only one canoe to cross, and the government forces took advantage of to bomb them. Only half of the rebels managed to cross under the command of Uribe Uribe, who tried to attack the aggressors, but was rejected; the other half remained behind under the command of Vargas Santos and Benjamín Uribe fled into the jungle, eventually disintegrating, although his commanders managed to reach Venezuela. Uribe Uribe's group was reduced to him and three companions who escaped on a raft at night down the Magdalena River, and after a long journey they reached Venezuela.

The liberal rebellion in Santander had ended and a pacification process began immediately, rebel guerrillas continued to operate in the department although never with sufficient force to threaten government control of it. But contrary to expectations, the war continues because Vargas Santos, Uribe Uribe and Herrera managed to escape and the government failed to convince them to put down their weapons. Any chance of victory for the rebels was over by July 1900, they had failed in regular warfare, facing the army in the open field in major battles. Government forces had prevailed because well-trained and armed officers and soldiers began to enter operations during the war.

Most of the rebels were dead, exiled or in prison, but a small minority, under the command of their leaders, began to organize a new insurrection starting in August, taking advantage of the chaos caused by a coup d'état by the conservatives historical.

Coup d'état

During the war, the ruling National Party, headed by President Manuel Antonio Sanclemente, sought to negotiate with the so-called historical conservatives who were in the Conservative Party, including some of these in the government to use their support in the need to expand the military apparatus, in turn, in the attempt to pacify the country, certain directorial liberals such as Nicolás Esguerra were included in the cabinet as commissioner to deal with the Panama Canal company, and Carlos Arturo Torres as his secretary. However, this would prove useless, since the historical conservatives were in conflict with the nationalists and had affinities with the liberals, who also had no intention of negotiating with the government.

Thirty-one historical figures, between civilians and soldiers, quickly began to conspire to carry out a coup d'état; the conservatives contacted the head of liberalism, Aquileo Parra, and offered him the presidency in the mid-1900s. The conservatives had planned that after the coup they would seek an honorable peace without reprisals (which would not be carried out), the call for a constituent body for elections, freedom for political prisoners, and separation from the government of Arístides Fernández, who was hated by liberalism.

The Minister of War, Manuel Casabianca, indirectly facilitated the coup by naming General Jorge Moya Vásquez, one of the 31 historical figures behind the plot, as commander of Sumapaz's forces. General Moya, with a force of a thousand men, moved from Soacha threatening to march on Villeta and, indeed, he headed for Bogotá, where he arrived in the afternoon of July 31. But the indecisive attitude of a large part of the army officers and the absence of Marroquín made Moya doubt the outcome of the situation and he resigned before General Casabianca.

This created great tension in the Bogotá garrisons that had to negotiate. The coup took place in the afternoon of July 31, 1900. Police commander Arístides Fernández guaranteed the movement's success by dispatching a force to appoint José Manuel Marroquín Ricaurte as president of Colombia, while Sanclemente was informed in his private residence after 300 men were sent to Villeta where he was, despite being protected by 500 soldiers, they did not resist and Sanclemente would be arrested.

After this, Marroquín insisted on continuing the war and appointed Arístides Fernández as the new Minister of War, the war would continue for another two and a half years.

Second phase

The nationalist government was deposed from power by the conservatives, who took control of the state and military institutions. This was despite two unsuccessful attempts to restore Sanclemente to power.

Meanwhile, General Uribe Uribe took advantage of the chaos produced to launch a new military campaign, but for this he needed the support of an external government to obtain weapons, supplies, supplies, men and a secure base. He sought the help of the government of the country where he was taking refuge, Venezuela, a nation that became a sanctuary for the exiled rebels, where they organized and began to launch a series of campaigns into the interior of Colombia. Over time they ended up dividing into Warmongers and Pacifists. The Venezuelan government eventually agreed to give them ammunition, supplies, and weapons thanks to President Cipriano Castro's sympathies for their cause. Castro saw himself as a new Napoleon Bonaparte or Simón Bolívar whose mission was to liberate the rest of America from South of conservative governments and form a great Bolivarian confederation with Ecuador and Colombia with him as president and Eloy Alfaro and some Colombian liberal as vice presidents. Product of this he carried out an interventionist policy in neighboring countries. This was the main cause of the war lasting so long, and because of this support he had to face the uprising of the conservatives in his country with the support of the Colombian government. Castro came to power after his victory in a military uprising carried out in October 1899 against President Ignacio Andrade.

Uribe Uribe's expedition would go to the department of Magdalena, which had little military protection as a result of its secondary role in the war and the reorganization produced after the coup d'état. After the capture of Riohacha (where a liberal rebellion broke out) in November 1899, there were no new confrontations, although the conservative authorities never came to control the interior of the region, which was left vulnerable to a possible liberal offensive, as it finally did..

A first invasion occurred in February 1900, when a column of armed and Venezuelan-trained men led by General Justo Durán captured Riohacha and immediately began recruiting volunteers, totaling 2,000 men. Despite this initial success, Durán did not initiate new actions losing the initiative gained. Only in June did he launch a land attack on Santa Marta with the support of two warships, but before beginning the assault he changed his mind and fell back to Riohacha. After this, the fleet betrayed Durán and returned to Venezuela, where they informed Castro of his inactivity, for which reason, disappointed, he stopped sending him supplies.

Seeing that control of the Magdalena was vital for the outcome of the war as it was the main transportation route between the coast and the interior of the country, Uribe Uribe decided to launch a campaign to cut off the flow of enemy supplies. From the department of Bolívar he planned to advance with a guerrilla column to the banks of the river; after that General Durán had to march to where he was, since Uribe Uribe would be sent with supplies that Durán needed to gain control of the riverbed. Vargas Santos sent a message to the local commanders indicating not to accept Uribe Uribe as his superior commander, but this was ignored and they joined the already legendary liberal general en masse when he arrived in Bolívar.

The Caribbean Campaign

Uribe Uribe decided to attack Magangué, a town and port located on the banks of the Magdalena, which he captured in June 1900. However, army units came out to meet them and they were forced to retreat into the jungles.

Seeing that it would be impossible for him to win without securing a steady flow of supplies from Venezuela and his supporters in New York, the liberal general traveled to Riohacha in December, ordering local commanders to keep their guerrillas active in his absence. He ended up personally traveling to Caracas to ask Castro for help, but he refused, then he tried to get the support of the Latin American exiles in New York, but they were more concerned about the events in Cuba.

The rebel invasion of Venezuela

However, by that time the liberals were defeated and their leaders refused to accept it. So much so that on April 12, 1901, Uribe Uribe published a famous manifesto where he exalted the liberals not to accept the peace terms proposed by the conservatives. This occurred after a peace project designed by Uribe Uribe himself, where the liberal guerrillas would demobilize in exchange for a minority representation in the Colombian Congress, was rejected, but President Marroquín ridiculed it along with some liberal sectors who labeled it of traitor. The main reason why Marroquín rejected the proposal was his complete confidence that the army could defeat the last pockets of liberal resistance in a few months. In addition, he was determined to put an end to the sanctuary that Venezuela had become for his enemies, for this reason he began to enter into conversations with the Venezuelan conservatives exiled in his country, the most prestigious of whom was General Carlos Rangel Garbiras, who was already organizing an expedition to invade his country with the support of some Colombians.

Before the invasion and to achieve peace with Marroquín, José Cipriano Castro had to accept complete submission to the Colombian government, losing part of his prestige as a leader. Castro was waiting for Uribe Uribe, who was in New York to organize the Colombian liberals to reject said expedition. The Venezuelan president organized his defense in San Cristóbal under the command of General Celestino Castro Ruiz, President Castro's brother. Uribe Uribe traveled quickly to support the defenses. On July 15, he had gathered more than 1,500 men, insufficient to invade Santander (only on the border the Conservative government had installed 4,000 troops). The Colombian government learned that Uribe Uribe's troops were very close to the border and had the possibility of destroying it once and for all, so they decided to go ahead of Rangel Garbiras. Destroying Uribe Uribe and starting a conservative rebellion in Venezuela were the objectives of the offensive.

Aware of this, Castro wrote a manifesto calling his supporters to resist any foreign invasion on July 18. On the 26th of the same month, the Colombian offensive began in Venezuelan territory, rapidly advancing to San Cristóbal, the capital of Táchira. There were about 5,000 expedition members against what they believed were about 300 Venezuelan soldiers, the usual garrison of the city, plus a few hundred Colombian militiamen. Rangel Garbiras was unaware that, aware of the campaign, Castro had concentrated more than a thousand of his own regulars and the entirety of Uribe Uribe's forces, who, although they continued to be clearly outnumbered, were located in excellent positions. On the following day Rangel Garbiras organized his forces into five columns while some shooting took place in the vicinity of the city.

Finally, on the night of July 28, the decisive battle of San Cristóbal began with the assault of the conservatives, but the liberals were located in very solid positions and rejected them. Fighting continued until the next day, when attempts were made several times to outflank the defenders' positions, without success. Finally, the Conservatives withdrew, leaving hundreds of dead and wounded on the battlefield, as well as significant amounts of war material that were used by their enemies. The success of this defense gave the Liberals significant booty, but above all, It raised their depressed morale, which led to the war lasting until 1902, when there was no longer a logical reason for that, the liberal guerrillas rose up in arms again with a new impetus and violence, the conservative government could no longer assume about a month before the country was practically pacified. Castro for his part used the victory to secure his position inside Venezuela and managed to start negotiations with the Colombian government since neither wanted to risk a full-scale war with his neighbor, however, these did not prosper.

Venezuelan invasion of Magdalena

Castro finally decided to launch a punishment campaign, although limited. While Colombian troops accumulated massively on the border between Táchira and Santander with a general basis in Cúcuta, it was decided to launch an offensive for a less protected sector, Magdalena, where liberals had broad popular support. To support the campaign, the liberals reactivated their guerrillas in the region and planned to take Riohacha. At the beginning of August, about two hundred Venezuelan soldiers crossed the border to La Guajira, the liberal troops are joined; At the beginning of the next month they joined a reinforcement of 1200 Venezuelan regular with several cannons and a machine gun, in addition to rifles and ammunition for their local allies. His goal was Riohacha, defended by 400 Colombian regular. Castro appointed General José Antonio Dávila, but he never had the acceptance of the liberal Colombian chiefs who wanted one of them in command of the column, so many of them deserted. Reinforcements were sent by the Bogotá government to reinforce Riohacha, so Dávila decided to take it before they arrived.

Dávila understood that a direct attack on Riohacha would be a suicide, so he moved part of his forces east of Carazúa to deceive the enemy garrison making them believe that they were attacked by two armies at the same time; The conservatives would send part of their forces to Carazúa leaving Riohacha unprotected, being able to attack her with the rest of her troops. The conservative troops would panic and evacuate or surrender in the city, after which the liberals could attack Santa Marta or Barranquilla, in addition to controlling the channel of the Magdalena.

On September 12, the plan was held. The liberals approached Carazúa, but the conservative troops who went out to defend the town quickly returned to the vicinity of Riohacha without going into combat. Any attack would be a failure. That is why they spent the night watching the population without attacking, until finally the 1100 conservative reinforcements supported by several cannons and machine guns under General Juan Tovar. At 11:30 a. m. On the 13th, the 3000 Venezuelans and liberals decided to launch a desperate assault supported by their artillery. Dávila could be forced to launch the product of his duty to recover the honor for his country. The assault resulted in a fierce battle called Batalla de Carazúa with large casualties for both sides especially for Venezuelans and liberals, until the defenders They forced to flee to the liberal guerrillas and without support the Venezuelans fled back to their country with serious and even the riders of the Wayuu Indians under the command of José Dolores Arpushana, killed or captured the Venezuelan survivors which implied that the government of Moroccan will reward the Arpushana chief with 100,000 pesos of the time. Much of the Venezuelan war material remained in the hands of Colombian troops, this Carazua disaster implied that Cipriano Castro Venezuelan dictator culminated their support for Colombian liberals.

Second rebellion in Panama

After the earlier failure of the Liberals, the government sent military and naval reinforcements. The Liberals were reduced to small armed bands scattered in the interior that engaged in guerilla warfare, sabotage, looting, assaults, and atrocities against anyone who did not cooperate with them. Their most famous commander was Victoriano Lorenzo, and they continued to receive supplies and weapons from Nicaraguan President Zelaya, who had forced Porras to be replaced as leader of the exiled liberals by Domingo Díaz, who did not have much support among his men. amphibious invasion of the isthmus landing on September 16, 1901 in La Chorrera, preparing to unify the armed bands and plan their next step. He spent several months in the area, but the government did not attack him, which was seen as a sign of weakness.

The government did not react well, it just sent reinforcements from Barranquilla by land. Finally, Governor Albán decided between reinforcing Panama City or attacking the rebels, and he opted for the latter. He marched on November 17 to Colón with the bulk of his troops in his fleet, leaving a garrison in the departmental capital. He hoped to launch a surprise attack against La Chorrera and achieve another victory to enhance his personal prestige. The Liberals advanced towards Colón but immediately fell back towards their base. Albán decided to try to reach them with most of his troops, sailing along the coast, leaving the city weakly garrisoned. However, the liberals had deceived him, while most of them retreated to La Chorrera, pursued by most of the enemy soldiers, a detachment of two hundred guerrillas attacked Colón. Meanwhile, in La Chorrera the Liberals prevented their enemies from landing by bombing and machine-gunning the landing boats. In this way, Columbus fell into insurgent power on November 19.

The Liberal success freed the advance to Panama City. General Albán tried to recapture Columbus, which was prevented by the United States ambassador, who through a message on the 24th offered to send North American marines to guarantee peace in the region, while in the Caribbean Sea there was a American fleet ready to land. The rebel victory also led the Colombian central government to speed up the dispatch of reinforcements with the warship Próspero Pinzón. Finally, the liberals, certain of their defeat, capitulated and handed over the city on November 28, but to the marines, who immediately entered it to prevent its destruction before the almost inevitable attack by General Albán.

Shortly after this, the rebel bands disintegrated and the Americans occupied the main route that connected Colón with Panama City. Given this, General Albán planned to expel them from the isthmus as soon as the reinforcements arrived, but the central government forced him to accept what had happened and political negotiations began immediately to resolve the conflict, leaving the isthmus in Colombian hands. Following this, the central government once again focused its efforts on other regions of the country.

The Plains and the Caribbean

Meanwhile, the Llanos region had fallen into the hands of local liberal guerrillas, who soon extended their operations to the departments of Cundinamarca and Tolima. His exiled colleagues in Ecuador and Central America were planning to invade Cauca and Panama again. Aware of this, the Colombian government sent reinforcements to the last two regions.

From Táchira, Uribe continued to manage the shipment of supplies to the rebels operating in Santander, but over time, the guerrilla units were surrounded, destroyed or surrendered. Because of this, it was very difficult for him to find volunteers among his fellow exiles, fed up with the war, to launch a new expedition. Another factor that worked against him was the high concentration of conservative troops on that part of the border. In addition, he realized that Marroquín and Castro began to negotiate peace so he realized that he could soon run out of support in exile, so he decided to launch a new offensive. He had two options, to the north, to Magdalena; or to the south, to the Llanos, near Bogotá. Due to the failure of September of the same year in Riohacha, and the propaganda desire to imitate Simón Bolívar's campaign of 1819, which ended in the battle of Boyacá when he suddenly crossed the Andes through said region, Uribe Uribe opted for the second alternative.

On December 24, 1901, he left Táchira entering the jungle with a column of well-armed followers, arriving in the vicinity of Tame on January 24, 1902, already in the Llanos, being immediately well received by the rebels local. As usual, Uribe Uribe's charismatic personality allowed him to win the support of the residents. They continued marching south, skirting the Andes, to Medina, which became his base of operations. In Gachalá the conservative troops found out about the presence of the liberal column and the central government ordered them to attack it, being defeated and dispersed on March 12. After this, the government of Bogotá finally decided to attack Uribe Uribe by sending troops to the region. However, the liberal commander had enough problems with the lack of discipline from his local lieutenants.

This had not prevented him from ordering his officer Juan MacAllister in February to invade the Bogotá savannah and capture some towns and farms in the region (although he never attacked the heavily defended Colombian capital) but it did weigh on him on the campaign. After this initial success, Uribe Uribe went with the rest of the troops and the artillery that he had with him. MacAllister tried to attack Soacha with a massive attack from all directions, but failed as many of the guerrilla bands did not want to attack (23 February). After this defeat, the Liberals had to return to the Llanos along the road between Quetame and Villavicencio, pursued by the army. Uribe Uribe, aware of this, took the defenseless Medina and went out to meet his men, at which time Gachalá was victorious, forcing the government to stop the persecution of him and shelter his men in Villavicencio. Uribe Uribe managed to join his men and there they occupied the surroundings of the city. He had about 6,000 men against 4,000 Conservative troops, but the government also saw an opportunity to surround and end once and for all the threat posed by the insurgent leader.

The victory of Gachalá gave new air to the rebellion, Uribe Uribe once again sent troops to the Bogota savannah, some two thousand armed men with part of the important military equipment captured on March 12, led by himself. However, the indiscipline of his men led to a terrible defeat (and near capture) when he attacked Guasca on March 21. He escaped with his men to the elevation of "El Amoladero", where he established a line of defense, the following day the conservatives who were chasing him arrived, and attacked him but unfortunately for the liberal leader several of his units had not occupied the positions assigned to them. Although the first assault was repulsed, the next one was less successful and the Conservatives collapsed their defensive line and forced the rebels to flee. The liberal commander again miraculously escaped capture or death. However, he managed to restore order among his defeated men, establishing a new defensive line on the 25th, but noting that it would be impossible for him to face the conservatives again in open combat, he ordered them to withdraw and abandon the positions of he. The Conservatives launched a massive assault on the Liberal column in disarray and their victory was complete. Capturing an important part of the weapons of the rebels. On April 2, Uribe Uribe and the survivors of his column joined the Liberals surrounding Villavicencio. However, his low morale and constant desertions led the rebel leader to call off the assault on the city and take his men to Medina, where he informed the local chiefs that the campaign was lost and they should demobilize; after this he returned to Táchira and his men dispersed.

Uribe Uribe was then in charge of smuggling supplies and weapons from Curaçao to the Atlantic Coast. In the first region it happened that after their defeat in Carazúa the previous year, the liberal guerrillas had almost finished their war operations, but thanks to the contributions received, they were able to reactivate and begin to reorganize, establishing Valledupar as their base of operations. The attempts of the conservatives failed because of the inhospitable terrain, which served to demoralize them. In this way, it was relatively easy for the insurgents to capture Riohacha on April 16, 1902. The capture of the city gave the rebels a base of operations important enough for Uribe Uribe to once again plan an expedition and prevented the conservative central government from sending reinforcements to Panama, since the Magdalena road was blocked.

Third rebellion in Panama

After the capitulation of the Liberals in Colón (November 28, 1901) hostilities in the region came to a relative pause. Meanwhile, the conservative government had its war fleet trying to re-establish the passage through the Magdalena riverbed.

General Herrera planned to take advantage of the moment to introduce weapons by sea into the country and restart the rebellions in Cauca and Panama. Two expeditions were planned: one for the isthmus and another to take Tumaco and invade the center of Cauca. He opted for the latter, while a flotilla of men, arms, and ammunition traveled south. Herrera used most of his family fortune to buy and arm a ship, Almirante Padilla, which was dedicated to to launch attacks against boats on the Pacific coast. The ship attacked Tumaco on October 16, 1901 to try to restart the rebellion in Cauca. Faced with the presence of US troops in Panama, Admiral Padilla left the south and went to the isthmus to support the rebels.

The ship dedicated itself to attacking enemy ships, stealing their supplies, weapons and ammunition. It arrived at its destination on December 24 with a flotilla of some 1,500 well-trained and equipped men. Governor Albán took control of the Lautaro, a large Chilean merchant ship perfect for transporting large numbers of troops, and armed it with cannons keeping the Chilean crew in charge of steering the ship. On January 19, 1902 the Lautaro was sent with a battalion on board to find and finish off the rebels but she was not given permission to sail until the next day, but during the night the ammunition exploded. The vessel was immobilized and on the night of the 20th Admiral Padilla arrived unexpectedly and immediately opened fire against it; During the combat, General Albán was killed and the Lautaro was rendered unusable.

Herrera still had to face the men of General Francisco de Paula Castro, who was left in charge of government troops in the department. The liberal general decided to attack the conservatives stationed in Aguadulce, he sent scouts to watch his enemy from the nearby forests and to choose which positions to occupy. On February 23 the attack took place, being surrounded by some two hundred soldiers, and after hours of desperate resistance, forced to surrender. Castro withdrew at the very beginning of the combat with the majority of his troops, thus being able to save himself from a major defeat; without knowing the reason yet, they did not choose to return to Panama City by the main highway, but took refuge in inhospitable mountainous islands called Bocas del Toro. Herrera sent five hundred men to the islands from David to start operations against his enemies.

In the departmental capital, meanwhile, General Víctor Salazar took office as the new governor. The rebels attacked Bocas del Toro and captured it in early April, but only to notice how a military fleet sent from Barranquilla left them isolated in them and forced them to surrender. However, the US ambassador ended up intervening to ensure that the rebels could evacuate the islands and thus be reintegrated into Herrera's troops. In this way, an apparent conservative victory became a propaganda success for the liberals.

The rebels were able to receive supplies from Nicaragua along the Pacific coast, since Admiral Padilla was blockading Panama City, although the Caribbean coast remained in conservative hands. Salazar decided to launch a land offensive and the Liberals fell back to Aguadulce, giving the impression of being too weak to resist. Salazar asked for reinforcements to put an end to the revolt but at that moment Uribe Uribe's expedition to the Llanos took place and he was denied any help.

It was then that Admiral Padilla traveled to Nicaragua to rearm and carry out repairs, and Salazar decided to attack the rebels in Aguadulce. He sent two columns, one under the command of General Luis Morales Berti to Antón and another led by General Castro to the Santa María River with the intention of surrounding the insurgents and annihilating them. On June 10, Morales Berti arrived in Antón and shortly after Castro changed course and arrived in that same city, Morales Berti opted to advance to Aguadulce and Castro to Bocas del Toro. The Liberals opted to withdraw from Aguadulce to Santiago de Veraguas, hoping that the enemy would not follow them along such a difficult route, but seeing that Herrera was doing so, he had no choice but to attack the Conservative column. At that time (mid-July) they withdrew to Aguadulce.

The government commanders knew that the insurgents were equipped and trained as well as having a vast numerical superiority, so retreating was their only option. The withdrawal began on July 22, but Salazar decided to send reinforcements, hoping to put an end to the rebels. A merchant ship was chosen for this mission, the Boyacá, but it ran into the Almirante Padilla on the 30th of the same month on the coast near Aguadulce, being forced to surrender and his troops were taken prisoner. The rebel victory demoralized the conservative soldiers who had to choose between going back to Panama City through the dense jungle or face and fight. Aware of what had happened, Castro began to do the same. Both generals chose to meet in Aguadulce, where they entrenched themselves. Herrera began a long siege supported by his artillery and the defenders began to starve until they surrendered on August 27.

But the rebels lost too much time in the siege of Aguadulce and much-needed reinforcements arrived in Panama City by land. The war then ended in a new ceasefire, with the area between Aguadulce and the departmental capital as a no man's land, separating both sides.

End of the war

The events of the Isthmus made the need to block the Magdalena route imperative to prevent the passage of central government reinforcements towards said region. Uribe Uribe tried to organize an expedition to Magdalena, but the liberals in exile denied him support. They sent instructions again to the local commanders so that they did not recognize it as commander of the Caribbean coast, but these were ignored and Uribe Uribe landed near Riohacha on August 14 of that year.

Uribe Uribe began to negotiate peace, but knowing that his reputation as the liberal leader was at stake since he had promised to block the Magdalena route, he decided to launch a last offensive. Instead of attacking Barranquilla, an impossible goal for his forces, he opted for Tenerife. The liberal commander sent part of his forces to the north between Ciénaga Grande and Santa Marta to distract the enemy and prepared a thousand men to capture Tenerife. He also achieved reinforcements from the guerrillas of the neighboring department of Boyacá, and on September 18 he attacked his goal with the support of some ships and two cannons, he defeated the small local garrison and thus blocking the channel of the Magdalena. However, Uribe Uribe learned that the government sent troops to recover the city and decided The slow bureaucracy, a time of two months before the reinforcements arrived, period that the liberals could take advantage of.

Uribe Uribe attacked Ciénaga on October 13 to have Santa Marta at his disposal; The little local garrison took refuge in her barracks, which ended up being dynamited, some managed to flee to the small ship NELY GAZAN , which armed with small cannons bombarded the rebels and by little kills their leader. This did not change the course of combat or campaign, the Caribbean rebels agreed Herrera, who knew that when the conservative reinforcement battalions arrived would be defeated.

The agreement required Uribe Uribe to intercede to end the war in that region, so he sent a letter to Herrera asking him to negotiate an agreement, but he had been negotiating in secret months.

Dutch and Wisconsin's treaties

The peace treaties were signed at the Neerlandia hacienda (located in the Banana Zone of Magdalena, near Ciénaga) on October 24, 1902 by Florentino Manjarrés, governor of Magdalena, ending the the Thousand Days War. Although the fighting lasted until November of that year in Panama between the ships Almirante Padilla (liberals) and the Lautaro (Chilean property, expropriated by the conservatives), combat that had been present since the end of 1901 and in which the latter were defeated in front of Panama City on January 20, 1902. With the death of General Carlos Albán, who was traveling on the Lautaro, the isthmus was left without a representative, being named Arístides Arjona.

Later came the constant threat of the US Navy sent by the government of Theodore Roosevelt to protect future interests in the construction of the canal. Benjamin Herrera's liberals laid down their arms without fighting the external threat.

The final peace treaty was signed on November 21, 1902 aboard the American battleship USS Wisconsin docked in Panama Bay. The treaty was signed by General Lucas Caballero Barrera, as chief of the General Staff of the United Army of Cauca and Panama, together with Colonel Eusebio A. Morales, Secretary of the Treasury of the Directorate of War of Cauca and Panama, representing General Benjamín Herrera and the Liberal Party; and by General Víctor Manuel Salazar, Governor of the isthmus, and General Alfredo Vázquez Cobo, Chief of Staff of the Conservative Army on the Atlantic Coast, the Pacific and Panama, representing the government.

Wisconsin Prostrate

To the rest of the country, the news of the end of the war arrived late. Given the remoteness of the Isthmus of Panama with respect to the rest of Colombia, and the fact that the few telegraph lines were interrupted in several of their sections, communications remained in the hands of couriers and transhumant merchants.

Violent events continued to occur in the country, such as the execution of Victoriano Lorenzo by order of General Pedro Sicard Briceño in 1903, an event considered one of the triggers for the subsequent separation of the isthmus.

On June 1, 1903, the government declared an absolute cessation of hostilities in the country, proclaiming that public order had been restored.

Consequences of war

After the war, Colombia was devastated: there was a great economic crisis that worsened with the separation of Panama on November 3, 1903, and the debt from military expenses incurred by the government. The country was impoverished, its industries and communication routes were destroyed, and the external and internal debt were considerable, so much so that the pound sterling, the exchange rate of the time, had gone from 15.85 pesos in 1898 to reach to be quoted in 1903 at 505 pesos.

In turn, due to the defeat of the nationalists, Law 33 of 1903 was signed, which established the gold standard to control the monetary issue, collecting the currency that had been issued during the Regeneration. It prohibited any new printing of fiduciary currency and added that it had suspended the issuance of paper money as a fiscal resource through Decree 217 of February 1903.

During the war, a total of 75,000 men were mobilized by both sides, who even recruited child soldiers, leaving a maximum of 39,000 casualties. The country struggled to protect the delicate balance of peace for approximately forty-five years.

Everyday life in war

The war produced great changes, among the most important is daily life, which was affected to the extent that people must adapt to other realities, such as the change of housing, for an open space and little sure, the dress, the best clothes for Sunday or mass day will no longer be taken into account, but any garment will be useful to protect oneself from the weather conditions and even from nudity, food will be scarce on the fronts of combat, because they did not always or rather almost never have the necessary food to feed the troops. The ringing of the bells in the church to enter mass, will determine the proclamation of an anti-partisan speech in favor of a sector and the main square goes from being a pleasant meeting space to being the point of fierce and ruthless recruitment.

The temples as spaces for sociability, will have a strong significance in the proclamation of hate speech, based on the proclamations made by the priests, "the church, fighting against those who opposed its earthly power, fanned the bonfire politics and found respite from the conservative governments" the foregoing if one takes into account that this institution dominated all stages of public life and went hand in hand with the conservative governments. Specifically, we found the following case: “Bishop Agustino Recoleto Ezequiel Moreno Díaz, a personal friend of Miguel Antonio Caro, and a prominent anti-liberal fighter. From his arrival in the city of Pasto, this man began a feverish partisan activity aimed at making the liberals the enemies of God. From his pen, he published in 1897 a booklet entitled: Either with Jesus Christ or against Jesus Christ. Either Catholicism or liberalism, in which, displaying the purest Manichaeism, they sought to give a divine reason to the fight of Catholics against liberals", ratifying the preponderant role of the church.

On the other hand, the displacement will no longer have an interest in walking or enjoying a place, but will be the objective of military recognition and use of the difficult or easy geography for combat and the ability to adapt or not to the new conditions that the places offered.

Forced recruitment will perhaps be a constant in all regions of the country, since it was not easy to make the decision out of conviction to go to war when you were leaving behind a life, a family, a job or just a space of "comfort", which offered tranquility, as Jaramillo points out: "This is the modality of force, subjugation and threat, where individuals do not enjoy logical alternatives to avoid conscription and where reason is subordinated to edge of a bayonet", where physical punishments were even presented to those who refused, with the final result being linked to the ranks. Another form of recruitment is the confinement, generally practiced by the government, where public spaces such as market squares and churches were fenced off. But at some point there were also "volunteers", although most certainly in a smaller number, and they were those who opted for war to obtain social prestige or exalt their party. As for training, there are military tactics that allow knowing the modus operandi before and during combat, such as the Maceo Code, widely used in liberal troops, and some forms of training by the official army. that can be established throughout the investigation.

In popular culture

- The colonel has no one to write by Gabriel García Márquez, published in 1961, is a novel about a retired colonel, veteran of this war, who was present at the signing of the Treaty of Neerland and hopes to receive the pension they promised him.

- Hundred years of solitude also by Gabriel García Márquez, published in 1967, narrates the story of Macondo, a fictional Colombian people. The story of the characters who inhabit it is described. The Colonel's character Aureliano BuendiaHe participated in the war. According to the author himself, he based the figure of Buendía in the liberal general Rafael Uribe Uribe.

- Memory of my sad sluts, by García Márquez, published in 2004, includes the war event setting the date of the death of the protagonist's father on the same day of the signing of the Treaty of Neerland.

- Charm (2021), animated film Walt Disney Animation Studios set in Colombia, it shows a scene of violence and displacement that occurs during the conflict.

Contenido relacionado

Jota (music)

Boa

National Anthem of El Salvador

Journalistic criticism

Mari (goddess)