Old Regime

Ancien Régime (French: Ancien Régime) is the term used by French revolutionaries to designate the system of government prior to the French Revolution of 1789-1799 (the absolute monarchy of Louis XVI), and that was also applied to the rest of the European monarchies whose regime was similar. The opposite term to this was the New Regime (in Spain, Liberal Regime).

It can also be applied as equivalent to a time that would practically coincide with what is known as the Modern Age.

Source of expression

Although its use is contemporary with the Revolution, the greatest responsibility for its fixation in the literary field belongs to Alexis de Tocqueville, author of the essay The Old Regime and the Revolution. In that text it indicates precisely that "the French Revolution baptized what it abolished" ("la Révolution française a baptisé ce qu'lle a aboli"); Tocqueville confusedly opposed this concept to the medieval period, an opposition that became common in historiography during the xix centuries and first half of the xx, and which later historians have discussed, notably François Furet.

From the point of view of the reactionary enemies of the revolution, the term Old Regime was vindicated with a touch of nostalgia, following the literary cliché of "paradise lost" (or the Manriqueño "any past time was better"). Talleyrand said that "those who did not know the Old Regime can never know what the sweetness of living was" ("ceux qui n'ont pas connu l'Ancien Régime ne pourront jamais savoir ce qu'était la douceur de vivre»).[citation needed]

The application of the term to economic and social structures is attributed to Ernest Labrousse, and it was disseminated by the contemporary Annales school, with great acceptance in Spain through Hispanists such as Pierre Vilar or Bartolomé Bennassar. Its use in this sense, which was not usual before, became habitual by the authors of the third quarter of the xx century, such as Antonio Domínguez Ortiz, Gonzalo Anes or Miguel Artola, who ended up fixing the concept in Spanish historiography. The application of the term to the history of Spanish institutions dates back much earlier, but it seems that it also originated from French influence, as is the case in the work of the Hispanist from the late xix, Georges Desdevises du Dézert, collected by Antonio Rodríguez Villa in 1897.

Definition

From the point of view of historical materialism, the Old Regime can be defined as a socioeconomic formation, that is, the peculiar combination of modes of production and social relations for a more or less wide space-time scope, which builds its appropriate superstructure political and that is justified by its corresponding ideology. In this sense, there are three characteristics of an Old Regime society, namely:

- economic system: in transition from feudalism to capitalism;

- social relations: determined by the opposition between the state society and a bourgeoisie that cannot access the role of the ruling class that occupy the privileged elements;

- political system: absolute monarchy or, as little, authoritarian monarchy. The fundamental tension in this area is the one that occurs between the centralization of power and respect for the privileges of all kinds (personal, stamental and territorial), which maintained a large number of jurisdictions and jurisdictions.

Extension

The concept of the Old Regime can be properly applied to the kingdoms of Western Europe that tend to be defined since the end of the Middle Ages as authoritarian monarchies and, later, as absolute monarchies —both terms used by analysts of historiography, who they did not use the implicated ones. The first example was undoubtedly Portugal. By the end of the 16th century, only France, England, and the Spanish Monarchy can be added to the list. England will surpass the concept throughout the 16th and xvii leading to what has been called the nation state. The others, during the crisis of the Old Regime (1751-1848). For the rest of Europe, the concept is of problematic use (see section other European countries, in this same article). For the rest of the world, only America, during the period that it was colonized by the European powers, could (forcing the concept a lot) be considered something similar to the current model in its metropolises. American independence coincides with the end of the Old Regime; in fact, it contributes decisively to it. The other continents are colonized later, already in the industrial era or New Regime. The case of Japan represents a social economic formation that, in some way, shows similarities with Western ones, for which reason some authors have applied the concept of "feudalism" or that of "absolute monarchy" (not so much "Old Regime")., and it would be this similarity —as opposed to China, a hydraulic empire—, together with the non-submission of colonialism, which would explain the possibility of its accelerated access to modernity in the Meiji Era.

The impossibility of retrieving the concept to political entities of an earlier period, even in Europe, stems from the fact that medieval political forms were feudal in character, dependent to some extent on the Empire or the Papacy, or were some form of city-state; on the other hand, the nascent trade was still somewhat marginal, and the estate society (already defined) had not yet produced its final mechanisms and institutions. In no case do they meet the proposed requirements.

The temporal duration of the Old Regime would coincide with what we call the Modern Age: from the 15th century to the xviii. This is valid both for France (from the end of the Hundred Years' War to the French Revolution) and for Spain (from 1492 to 1808). However, some author, such as Arno Mayer, argues for the persistence of characteristics of the Old Regime in Europe at the end of the xix century and up to the First World War.

The French model

The Old Regime taken as a model developed in France, as the French monarchy of the Valois dynasty emerged from its confrontation with England in the Hundred Years' War, marginalizing rival Burgundy and subjugating most of the states more or less rebellious nobility (Normandy, Provence...). The return of the papal seat from Avignon to Rome after the resolution of the Western Schism meant a decrease in the control that the French monarchy had come to achieve over the Church, and Italy will become the main game board in the dispute for hegemony european. In that context, Louis XI would be a good example of an authoritarian king for the 15th century. Francisco I, in the first half of the 16th century, failed to prevail over his enemy Carlos V, neither in the European wars nor in the colonial expansion, but managed to establish an indisputable internal power. The turbulent period that would lead his successors into the religious wars of the second half of the xvi century will end with the brief but decisive reign of Enrique IV, who inaugurates the Bourbon dynasty. In the reign of Louis XIII and the minority of Louis XIV, leaders like Richelieu and Mazzarino skilfully concentrated royal power in the midst of a complicated European and internal situation (the Thirty Years' War and the Fronde). Its most finished paradigm will not be reached until the absolute monarchy of Louis XIV, who could call himself "the Sun King".

Identified, at least in theory, the interest of the State, that of the People and that of the King, progress is being made in the construction of a market of national dimensions, with the support of a colonial empire (which suffers great ups and downs at the risk of the continuous wars); the administration and taxes (the tax, the carving) are modernized, everything that estate or territorial privileges allow; the imposition of Catholicism is achieved (revocation of the Edict of Nantes) and control of the Church (Gallicanism); or French is recognized as the common language (and the cultured language of Europe, replacing Latin) and the vehicle of a thriving culture (Molière, Racine, Corneille) that dethrones the Spanish Golden Age, institutionalized in the Académie Française.

However, the accumulation of contradictions between the closed class society and the strength of the bourgeoisie led to the French Revolution of 1789, which was a model for other bourgeois revolutions that transformed European political systems into constitutional monarchies throughout the century. 19th century or republics on the horizon of the First World War.

The Spanish case

The Spanish model differed from the French in what Ignacio Vicent López called "a matter of style". The reign of the Catholic Monarchs was decisive in the development of this style, which was based on in the conscience of the Catholic monarchy. This system would continue with variations under the Habsburgs until the arrival of the Bourbons adopted the French mode, in what would become an absolute monarchy, although it could never get rid of the traces of the old style.

The success is undoubted and surpassed that of the French monarchy during the 16th century: an unparalleled territorial set is achieved (Philip II was able to say "the sun does not set in my domains") which, although not very cohesive, could be effectively governed from a center located in Castilla after the War of the Communities (1521) and the election of Madrid as the political capital (1561); A fabulous amount of tax resources are drained from Castilla (excise taxes, royalties, services of comprehensive courts, a royal fifth of American metal remittances) that are spent on European politics that identifies the interests of the Catholic Monarchy with those of the cause of Catholicism. The success is confirmed by the Black Legend itself, explained both by the reality of the cruel rule over America (of which the colonizers themselves were aware, solving it in the controversy of the natives), the repression of political dissent (which was forced assimilation or expulsion: converts, Moriscos; or the most minority behaviors considered unnatural and, only until the beginning of the century XVII the minimal pockets of witchcraft and Protestantism) and the impotence of their enemies, resigned to fighting the hegemonic power with anti-Spanish propaganda (the parallelism with the anti-Americanism of the century xx is clear).

Internal control is guaranteed by a growing bureaucracy —the polisinodial regime of the Councils—, which is implanted territorially through the viceroys in the kingdoms and the corregidores in the cities. The control of the privileged estates is achieved by the submission of the clergy (royal patronage, Cisneros reforms) and the nobility, accustomed to putting and removing kings in the Castilian civil wars of the Late Middle Ages, of which the war of the Communities they are the last episode. The king becomes grand master of the military orders —since Ferdinand the Catholic—, involves the aristocracy in his appointment policy (institution of the greatness of Spain with Carlos V) and makes it clear that, In exchange for exercising political power without interference, it guarantees them social and economic power (institution of mayorazgo, Laws of Toro). The demochamientos of towers —which even Gonzalo Fernández de Córdoba, the Great Captain, suffered, who was asked for the famous accounts of his management in Italy— are a clear symbolic message. The bureaucratic positions are a good hooking pennant for the lower nobility and the bourgeoisie. In the absence of a police force worthy of the name —because the Santa Hermandad was no more than a military body—, there was the information and repressive network of the Inquisition —whose submission to royal power proves its use in some notable case, such as the by Antonio Perez.

The failure became clear with the decline. The cultural brilliance of the Golden Age did not hide the fact that the economy, stimulated by the price revolution of the xvi century, entered into decline in the 17th century, a century of general crisis that will push southern Europe in particular towards depopulation, much more so in Spain, and even more so in the hitherto decisive Castilian center. Political solutions (monetary disorder, repetitive tax reforms) only aggravated the situation, and the most vigorous attempts at centralization (Union de Armas of the Count-Duke of Olivares) precipitated the crisis of 1640.

The change of dynasty in 1700 (Felipe V de Borbón) produced the channeling of the system towards an absolutism with similar characteristics to the French, which produced well-intentioned attempts, such as fiscal rationalization such as the Ensenada Cadastre, and also other enlightened reforms that they are not fully applied, such as those of Esquilache (expelled from power by the riot that bears his name after a liberalization of the price of wheat, hitherto subject to tax) or the file of the agrarian law, eternally processed, which sought to resolve the land hunger of the peasants. The French Revolution truncated the expectations of reformism.

The Old Regime lasted briefly in the XIX century until the Spanish war of independence, when, when the Constitution was promulgated of 1812 in Cádiz, the process of constitutionalism was opened. On the other hand, the term Ancient Regime had the same meaning as in France, despite the fact that the end of said regime was not as drastic as the French one. After the years of French occupation and the final defeat of Napoleon in 1814, the absolutist Restoration took place, which caused the return of Spanish politics to the Old Regime during most of the reign of Ferdinand VII. His shadow, although already out of power, continued to be present during the second third of the xix century with the Carlist wars, despite the succession of constitutional texts, the arrival of more or less moderate liberals to the Government —almost always after pronouncements— and the beginning of a modest industrialization. The Revolution of 1868 with the overthrow of Queen Isabel II of Spain did not definitively end the regression temptation, but already in a completely different context: the Restoration of Alfonso XII or the dictatorships of Primo de Rivera or Franco, no matter how much the latter recovered the nostalgia of the Empire, have another definition.

Other European countries

As the map at the beginning showed, the spatial situation of Europe was extraordinarily complex, which neither the treaties of Westphalia (Münster and Osnabrück, 1648) nor the later ones of Utrecht and Rastatt (1714) eliminated. What they did produce was a clear modernization of international relations, in a pragmatic sense that forgot medieval fantasies (inherited from the Dominium mundi) and religious fundamentalism still in force in the xvi. In 1648, the Madrid Habsburgs resigned themselves to the independence of the United Provinces and recognized Portugal shortly after, but they continued to weakly control Italy and Flanders, as well as an immense American empire whose management was increasingly problematic. Poland expands to the east and south. The threatening closeness of the Turkish Empire will continue until the siege of Vienna in 1683. The Scandinavian monarchies continue to dominate the Baltic, although they will abandon Central European affairs to the shattered German principalities, the main victims of the crisis of the 17th century, among whose ruins stands the nascent Kingdom from Prussia; already free of any interference from the Habsburg emperor of Vienna, who will concentrate his interest in his patrimonial estates in Austria. France, with a Louis XIV in a minority who continued the war against Spain while leaving his internal problems in the Fronde, temporarily controlled Catalonia until the Treaty of the Pyrenees (1659), which would divide it. England, mired in civil war, looks like a territorial pygmy that doesn't even control Scotland or Ireland (theoretically they share the person of the same king, and are torn between the simultaneous War of the Three Kingdoms); but it will be the giant of the future, by leaving the model of the Old Regime.

The Treaty of Utrecht, in addition to sanctioning the role of England as a power, provided Austria with the Spanish European territories and initiated the Franco-Spanish alliance (Family Pacts) that would characterize international relations until 1789.

For most of the Modern Age in England or the Netherlands, the term Old Regime is not applicable, since from the century xvi or xvii are in the process of economic, social and political transformation (up to such a point does not see discontinuity with the Contemporary Age, which Anglo-Saxon historiography calls Modern History the period from the Middle Ages to the present). In general, Old Regime could be understood as the period before the Napoleonic Wars.

Regarding how to fit each of the pieces of the rest of this European puzzle into the Old Regime concept, it was already noted at the beginning that, with the exception of France, Portugal and Spain, for In the rest of Europe, the term is insignificant: in divided Italy it can be identified with Habsburg rule (from the Battle of Pavia to Unification). In Central Europe, the decomposition of the Holy Empire, the rise of the Habsburgs, the Protestant Reformation, the Thirty Years' War and the rise of Prussia were drawing and blurring a panorama that was not clarified until German unification, already in the Contemporary Age. and with different criteria. Scandinavian countries developed national monarchies since the Middle Ages, although the definition of their ultimate personality did not come until the 20th century. Their economic and social evolution was somewhat similar to that of Western Europe, intervening in key intellectual processes (Renaissance, Reformation, Enlightenment) and becoming involved in European conflicts, especially the Thirty Years' War, in which they were decisive. Poland will not witness the formation of the strong monarchy that the Jagiellon dynasty attempted, but a noble republic that even played Western European politics with the election of a Valois king. Both the Turkish rule in the Balkans (from the capture of Constantinople to the wars of the late 19th century) and in Russia the tsarist era (from Ivan the Terrible to the Russian revolutions of 1917) cover the temporal dimension, but not the proposed characterization.: they are vast empires that cannot be measured with the criteria of the economic, social or political dynamics of the Old Regime of Western Europe.

Features

Economy and demography

Ownership of the land, the main factor of production, was subject to ties that included the mayorazgos held by the nobility, the dead hands held by the clergy, and the communal lands of the municipalities. The shared nature of this type of property, with the purpose of permanence over time, meant that it could not be freely disposed of, making the existence of a free land market impossible.

The same could be said of the free market for the other two factors of production: neither capital (suspected of representing a form of wealth not compatible with the noble or clerical way of life, and still far from the necessary accumulation for an industrial revolution) or work (unbecoming of the privileged, and considered a biblical curse) are freely sold in the market as merchandise subject to the free play of supply and demand.

Demographics

The growth in the size of cities (only a few: Paris, London, Seville, Madrid, Rome, Naples, Istanbul, exceed 10,000 inhabitants), despite functioning as demographic sinks and resources of all kinds, contributed decisively to the transition from feudalism to capitalism (the role of London was essential for the creation of a national market, that of Paris, intermediate; that of Madrid, a relative failure)., and the occupation of the vast majority of the population, that of the omnipresent rural areas, continued to be agricultural activities with very low productivity and yields, whose techniques evolved very slowly (the Braudelian long duration), condemning dependence on natural cycles and the periodic cyclically repeated subsistence crises, coinciding with the longest months before the harvest, when wheat was most expensive. It is no coincidence that these situations generated discontent movements known as subsistence riots, which in some cases could have political repercussions (Gatos riot, Esquilache riot, or the French Revolution itself) or in the worst case, famines that led to demographic crises (the so-called Malthusian trap). In fact, it is common in demography to speak of an Old Demographic Regime, which was characterized by high birth and mortality rates, little natural growth that was offset by years of catastrophic mortality, high fertility (eagerly required by families who own farms agriculture), compensated by celibacy (marriage, at very early ages that was sometimes delayed, did not affect the entire population) and very low life expectancy.

Trade

Trade was controlled by the guilds and trade associations, which controlled the quality and quantity of production that was carried out at all times. The aspiration to control economic life would claim that only those who belonged to a guild or had royal authorization could engage in the manufacture and distribution of products, from the richest of those forced to supply to the most miserable tablajero. The mission of controlling the fidelity of trade was a responsibility of the authority since ancient times (the mensa ponderaria of the Roman forum). In the Old Spanish Regime, it depended on institutions such as the Repeso or the Fiel almotacén, controlled by the city councils (or the Hall of Mayors in court), which monitored the correct application of the measures in exchanges, especially those of the food trade, the most sensitive for public peace. The metrological dispersion (the measurements of each locality did not coincide) was tried to be remedied with the prestige of some local measurements, such as the Burgos rod, but it had to be expected at the end of the Old Regime, with the scientific works of conformation of the decimal metric system. Access with the least possible intermediaries from the producer to the consumer was considered ideal, and resale and all kinds of price speculation were prohibited, even with religious sanctions (usury sin-crime), which does not mean that it was always achieved. as demonstrated by the practice of daily life in the market. Such a claim will not materialize effectively until the formation of the liberal bourgeois state of the New Regime, as Michel Foucault explains. The opening of the world to Europeans with the Era of the Discoveries brought about the first world-economy. The privileged companies took monopolistic control of routes and products (the cocoa from Caracas first for the Fuggers, and then for the Guipuzcoan Company; the supply of Madrid for the Five Major Guilds...). The first and most effective were the Dutch (WIC and VOC), followed by the English (East India Company and Merchants Adventurers, which is based on an earlier guild). Both nations (through the Amsterdam and London stock exchanges) lead the nascent commercial capitalism after the Antwerp sack, which until then was in charge of draining the American resources extracted through the monopolistic House of Recruitment from Seville or the port of Lisbon.

Industry

The industry was hampered by excessive regulations and taxes. Internal customs existed; the weights and measures varied according to the regions; some items, especially cereals (the true basis of the poor diet of the majority of the population), were subjected to an obsessive policy of paternalistic protectionism, with which they either had to be consumed at the place of production, they were either subject to tax, or in any case made security of supply impossible; for others, customs duties were applied (not only outside but also inside the states) which in many cases annulled the exchange.

Therefore, there is no economic freedom or competition, since everything was controlled by the unions, by the Corporations or by the State itself, which on some occasions functioned as an economic agent itself: real manufactures such as those of weapons (the Royal Artillery Factory of La Cavada), or luxury goods (the Royal Tapestry Factory, the Buen Retiro Porcelain Factory, the Cristal Factory of La Granja) and royalties or salt and tobacco stores (the Royal Cigars from Seville and Madrid), brandy and playing cards. Mercantilism in its various forms, metalism, bullionism, Colbertism, is the economic doctrine that justifies the dominant economic policy: protectionism. In most cases, he gets the opposite of what he wants. Neither power nor the theoreticians of the time have reliable instruments of economic analysis, nor do they understand the functioning of the economic system (which is neither that of the non-existent free market nor that of medieval village autarky). Physiocracy and free trade or economic liberalism appear in the XVIII century as alternative proposals that are making their way in a situation of transformation of the system.

Society

The main characteristics of the Old Regime is the organization of society into three estates defined from birth: two privileged estates such as the nobility (secular) and the clergy (which in its upper part corresponded to the second sons of noble families) were above the rest of the people and the Third Estate or the Common (the peasants, the vast majority of the population, and the bourgeoisie, merchants or artisans). The rights of the people were not equal, but rather, legally, the lay and ecclesiastical nobles had a series of privileges that the bibs did not have. Although the estates are closed, they are not impermeable, and it is possible for a non-privileged person to pass to a privileged situation, due to ennoblement or entry into the clergy.

The role that the secularization of the religious orders, with the consequent confiscation and the end of the celibacy of the secular clergy, had in the Protestant Reformation is one of the issues that made the Old Regime move away from the countries that opted for it. It is the Catholic countries of southwestern Europe (and Poland) that are witnessing the triumph of the Counter-Reformation, which in social terms means the triumph of class society: the pyramidal configuration of the clergy, the three votes of the regular clergy, the celibacy of the clergy secular, the justification of the economic presence of religious institutions (it was even said, from the liberal-bourgeois position, that the Church, with tithes and dead hands, created the poverty that justified its existence) and its presence in all orders of life, public and private.

The historiographical interpretation of the nature of class society gave rise to a notable debate between those who, close to historical materialism (the Annales or Past and Present school), use the concept of class, and those who, from an institutionalist position (and also close to the sociological and anthropological functionalism of the emic perspectives as opposed to the etic perspectives), they prefer to speak of a society of orders. Thus, Roland Mousnier identifies honor, status and prestige as more significant social markers than wealth. According to this perspective, society was divided vertically according to social ranks (patronage or patronage relations between patron and client: maîtres-fidèles), and not horizontally according to class.

In particular, the elites of the Old Regime society can be understood as a privileged class made up of a nobility and a clergy identified in their economic interests and interpenetrated by the strategies of family bonding of land and positions in the Church, the bureaucracy, the army and the Court (according to the materialistic interpretation); or else an inhomogeneous set of orders such as the nobility of the sword and the nobility of the toga (noblesse d'épée and noblesse de robe) more different from each other than from the peasantry or the bourgeoisie (according to institutionalist or functionalist interpretation).

The role of the bourgeoisie has also been the subject of deep controversy, because if in some cases and periods it seems to be the main support of the monarchs to increase their power, in a mutually beneficial alliance in the formation of a national market and in detriment of the feudal nobility and clergy; in others it seems that the monarchy is nothing more than the superstructure that exercises power for the benefit of the traditional ruling classes, and the upper class bourgeoisie only waits for the opportunity to "betray" to their class and ennoble themselves, abandoning base and mechanical trades for liberal arts and professions, when not taking the definitive step of buying land, unequal marriage with nobles impoverished and the definitive ennoblement, many times by simple purchase before kings always lacking money. Whether for that reason, or for economic reasons, such as the ruin of the Castilian industry, unable to take advantage of the opportunity of the American market that does benefit the Northern Europe, the weakness or strength of the bourgeoisie marks the difference between some national cases and others.

The same could be said of the peasantry: freed from servitude in Western Europe since the Late Middle Ages (while in Eastern Europe it fell into it) it could find in the Old Regime an opportunity to participate in the productive surplus with the lords who would have to extract it in its entirety through extra-economic coercion, as predicted by the Marxist model. To what extent this is possible or not will determine the possibility of the emergence of the figure of the rich farmer (the proud Pedro Crespo of El Alcalde de Zalamea of Calderón or Camacho the rich man of Cervantes' Quijote) that can begin a primary accumulation of capital in the countryside. In any case, the famous response of the "villain" Pedro Crespo al "linajudo" Mr. Lope:

To the king the hacienda and the life

to be given, but the honor

is the heritage of the soul,

and the soul is only of God.

it reminds us, due to its provocative nature, that peasants could not aspire to the same kind of honor as nobles: for them it is not the bourgeois honesty of being reliable in business, but rather the opinion or fame that no one could question the continuity of blood, guaranteed by the chastity of the women in the family (and which Calderón himself was in charge of codifying in dramas such as A secret grievance, secret revenge). It was enough for him to be the son of something (nobleman), to come from an enlightened lineage, if possible come from Goths . At least the peasants, especially in the northern half of the Iberian peninsula (somewhat like the free-born Englishmen, who have no equivalent among the French peasantry) proudly participated in the Christian category. old, which imaginatively placed them higher than many nobles whom the Blight of the Nobility infamous for having New Christian ancestry. While the social gulf that separated the proud French nobility from the humble commoners it was considered something natural, and a guarantee of the distinction of the elites (although it also created enormous resentment that explains revolutionary violence), it was commonplace in the XVIII foreign travelers were amazed at the audacity of the British mob, who seemed entitled to shout and push anyone, regardless of rank, when they passed him on the street. In Spain, the traditionalism of the aristocracy, which imitated the clothing and popular culture of the majos (for example, bullfighting), was not a symptom of equality, but a weapon of social and ideological struggle against the French modernizers. Despite the opposition of most of the enlightened, the bullfighting public is a cross-class sample that enjoys a politically harmless capacity for democratic decision-making in the bullfighter prize, and the possibility of identification with the individual rise of a character from of the lower social strata, as will later happen with sport. The social function is clear, and not new: entertainment cushions conflicts (the Roman Panem et circensis, an expression paraphrased in the Spanish expression Pan y Toros) and provides social cohesion. and identity. Later, when the adjective had lost its revolutionary meaning, the term National Festival was coined to refer to the bulls.

Political system

The authoritarian monarchies that accumulated the political power that the nobility had in the Middle Ages base their power on mechanisms such as the army, made up of mercenaries that the king hired, although in case of war civilians were forcibly recruited for the country defense. The end of the medieval retinues controlled by the nobility gives this estate a new function, not of military power but of economic and social power, and its position in the Court next to the king will give it its measure of political power.

For the increase of their power, in the Late Middle Ages, the free cities (islands in the feudal ocean) represented a support for the kings against the privileged. From them it obtains the resources in the form of taxes on commercial activities, while most of the wealth, the rural properties of the privileged, is not subject to tax. Once the royal power was established, the king tried to restrict the functions of the representatives of the cities, whether they were the bourgeoisie, urban patriciate or however they wanted to be described. He almost never summoned the Cortes and, when he did, he always reserved the right to make the final decision. The Courts were made up of representatives of the three estates (nobility, clergy and third estate), but in the case of Castile (since those of the kingdoms of the crown of Aragon met separately) only the representatives of the cities were summoned., and to approve taxes. When representative institutions came to the fore (English Parliament in the XVII century States General in 1789), the model broke down.

The holder of the Crown has in his hands all the powers (executive, legislative and judicial), although in practice he has to use a huge bureaucracy and he appointed representatives who are commissioned by the government on his behalf, secretaries, ministers or in the Spanish case, a valid one.

Territorial discontinuity and confusion of jurisdictions was more the norm than the exception of political entities, both state and sub-state. The borders were changing and insecure, and there were a multitude of enclaves, exclaves, territories of special jurisdiction, and even with shared (Andorra) or alternate sovereignty (Isla de los pheasanes, and facerías in the Navarrese Pyrenees). When Felipe II wanted to get a clear idea of his possessions, he did not turn to the maps in the library of the Monastery of El Escorial, which would show him a confusing puzzle, but to Topographic Relations (a protostatistical effort only comparable to the Cadastre of Ensenada two centuries later) or the views that he commissioned Anton Van der Wyngaerde to take. The dream of natural frontiers (the France from the Rhine to the Pyrenees which in retrospect looks like its historical mission) is more of an idea of 19th century as the manifest destiny that brought the United States to the Pacific.

From the 17th century one can speak of the presence of an absolute monarchy that has the sovereignty of the State. This monarchy was justified on the supposition of the divine origin of power, from whoever receives it without intermediaries (for example, the nation or the people). The king only has to justify himself in the eyes of God. The most finished example is the France of the Sun King , Louis XIV, who found the best theoretician of him in Bossuet.

The king declared war and made peace; he commanded the armies; it determined the expenses and fixed the taxes; he appointed and dismissed officials and directed the entire administration. The provinces were administered by the intendants, with absolute and arbitrary power.

The king made the laws, which were the expression of his personal will, because although he had to take into account the "fundamental customs of the kingdom," such customs were contradictory and vague, and it would have been difficult to define them clearly. Its subjects did not actually have any right that was exercisable or enforceable before the State (which does not have among its functions to guarantee rights, as the rule of law will), although they did have a diffuse constellation of rights, freedoms and privileges, not universal but different according to the individual, family, corporate or territorial condition of each one, and an equally diffuse set of duties with the king, whose ability to demand their fulfillment was broader in theory than in practice.

In addition, the king directed the administration of justice, since it was dictated in his name and by officials he designated. Judicial torture was used to obtain the confession of the accused, who were tried in secret and to whom bloody corporal punishment was applied (branding with hot irons, the pillory, the whip) including a wide range of types of death sentences. appropriate to the category of the prisoner or crime (beheading with different weapons, beheading, hanging, bonfire, dismemberment...). The torture of Ravaillac, the assassin of Henry IV of France, happens to have been one of the most gruesome. by the head (the guillotine). In Spain the garrote fulfilled the same function (which, even though it was the same for everyone, could be graduated into vile and noble depending on the paraphernalia that surrounded it). The execution seems to have also been a macabre modernization, applied above all in the army.

Individual freedom was constantly threatened by the police, who could arrest anyone with a simple order from the king, the "sealed letter" (lettre de cachet). The cause of the arrest was not made explicit, but simply indicated that "such was the will of the king"; (car tel est mon bon plaisir). There was prior censorship, which was mainly exercised by ecclesiastical authority (the nihil obstat). Freedom of conscience or religious freedom was not granted, but the principle cuius regio eius religio (the king imposes religion on the subject) of the Diet of Augsburg was applied.

The French monarchy of the Bourbons, since the establishment of this dynasty, was skillfully establishing itself in power from a weak situation, both abroad (Spanish hegemony) and within, largely due to religious division not settled by religious wars. Henry IV, a former Protestant, had ended them with the Edict of Nantes, which made the Huguenot security posts a state within a state; the regencies in the minorities of Louis XIII and Louis XIV and the personality of the valid or ministers (Richelieu, Mazarin, Colbert), managed to make France at the end of the century the main power in Europe. Simultaneously, the Hispanic Monarchy entered a deep decadence to which both the accommodative and corrupt policies of the Duke of Lerma (valid of Felipe III) contributed, as well as the aggressive and reputable Count-Duke of Olivares (valid of Felipe IV), who By forcing the unstable territorial balances with his attempt at a Union of Arms, he provoked the crisis of 1640 and came within a step of effectively ending the Spanish Empire. Absolutism did not reach Spain until the Nueva Planta Decrees, after Felipe V de Borbón won the War of Succession (1715) both against his European enemies and those within the Iberian Peninsula (especially Valencia and Catalonia) aspired to continue with a Habsburg that is more respectful of territorial jurisdictions.

The inability to form absolute monarchies in other kingdoms can be exemplified by the English case, where the Tudors, an authoritarian monarchy that maintained the balance with Parliament while the social changes of the Reformation took place, gave way to the Stuarts, which in the struggle to increase their power, they literally lost their minds.

The above, and what the different cases would tend to more or less, is what could be considered the ideal model of absolutism. It was relative to what extent the so-called absolute monarchs could exercise such power, and it is even questionable if they would not even have the pretense of organizing public life in its entirety, since enormous spaces were left in which power is exercised by multitudes. of intermediaries (the noble "estates", the powerful ecclesiastical jurisdiction, the foral territories, and all kinds of corporations, such as town halls, guilds, universities...). The decision-making capacity of the kings was undermined by the chronic deficit of financial resources, which as soon as they are received (and even before) are spent on the army and the sumptuous luxury of the court (enormously necessary to maintain the prestige of the monarchy). and the fidelity of the nobility, attracted to their service).

In the 18th century there is a variant of absolutism, enlightened despotism, in which an absolute king exercises his power, in a paternalistic way, under the motto "everything for the people but without the people", but it continues to possess the sovereignty of the State, a Constitution is not necessary, the king's will is the law. More than in the unattractive personalities of Louis XV or Louis XVI, the exoticism of the French sought the model of the ideal monarch outside their borders; some as far away as Montesquieu, with his Persian Letters.

In Spain, José de Cadalso did the same with his Moroccan Letters. However, it is generally agreed that an example of this type of monarchy would be that of Carlos III in Naples and Spain, that of José I of Portugal (with his minister, the Marquis of Pombal), that of José II in Austria, that of Federico el Great of Prussia, and far from the model, that of Tsarina Catherine the Great of Russia. The friendship (however inappropriate this name is for such an unequal relationship) of enlightened people with a reputation for solvents, such as Voltaire, with one of these kings, should not make us forget that, as Johann Baptist Geich said, the wise man warming himself in his brazier does not it is precisely what neither the monarch nor the structure of which he is the top should fear.

Thought, culture and art

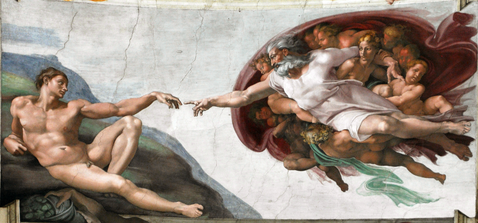

| The human being, center of intellectual reflection |

| Michelangelo, in The Creation of Adam (Left, ceiling of the Sistine Chapel, 1510), seems to want to pass the witness of medieval theocentrism to humanist anthropocentrism, before the Reformation and the Counter-Reformation close the step to the Utopia. Instead, The Final Judgment (Right., of the same author, in the same building, but on the wall of the altar, between 1535 and 1541), opens the way of mannerism, presenting an angry Christ, in a more pessimistic environment, behind the Holy of Rome, when Italy is already in the Old Regime, defined in this environment as the predominance of the Habsburgs. His nudes will later be accented by the moral turn of the Council of Trent. |

The relationships between what in materialist terms is called "ideological superstructure" and the most basic parts of the economic-social structure are very delicately fitted together and do not arouse much consensus.

The dominance of the Church in thought, education and culture remains overwhelming and, as in the Middle Ages, it remains the main justification of the political and social order and is not separated from the State (as much as they maintain a conflictive relationship, as evidenced by regalism, with different strength in France and Spain). However, in terms of its ideological role, since Humanism and the Renaissance, anthropocentrism succeeds theocentrism as a constant in cultural conceptions. Erasmism and its vicissitudes in Spain are a good example of the difficulties that advanced thought encountered even when enjoying royal protection, and it was not the only or the most notorious, as evidenced by the cases, persecuted by the Inquisition, of the professor and poet Fray Luis de León, Archbishop Bartolomé Carranza, or Mayor Pablo de Olavide. The climate in France was not more permissive, as the cases in which Voltaire was involved prove it. Protestant Europe tended to be more tolerant, without ignoring repression, as Miguel Servetus proved.

The University, which had been a thriving and developing institution during the Late Middle Ages, with the scholastic, will experience a period of distance from the scientific and cultural vanguard, which passes to other areas (academies, scientific societies), until the XIX century As an exception, as in so many other things, in the Spanish Monarchy the universities (Salamanca and Alcalá in the Peninsula and the newly created ones in America) are going through a golden age (Complutense Polyglot Bible, Salamanca school, neo-scholastic) responding to a clear social role: supply cadres to the bureaucracy and the clergy and raise or maintain the social condition of a triumphant nobility and an accommodating and claudicant bourgeoisie in terms of its dissolving capacity of the social economic formation. Its maximum brilliance was perhaps achieved as a consequence of the justifying debates on American colonization known as the Junta de Burgos and the Junta de Valladolid. The latter, held at the University of Valladolid, hosted the famous debate between Bartolomé de las Casas and Juan Ginés de Sepúlveda on the controversy of the natives and the Laws of the Indies (1550-1551). In 1527 this university had also been the venue for the conference that questioned Erasmianism.

University of Salamanca, the most prestigious of Spanish. More than because of his contribution to the increase of knowledge (acclaimed in neo-scholasticism), he was famous for the spectacular disputes between students and religious orders that controlled the different schools. The attempts to reform it (Meléndez Valdés) were useless.

University of Alcalá, founded by Cisneros, came to enjoy a spectacular flowering. Essential features of Spanish culture such as San Ignacio de Loyola, Quevedo or Jovellanos attended it. After the fallout he moved to Madrid, so the city became a ghostly setting of convents and barracks, until his second consolidation in the seventies of the century.XX.

That, on the other hand, it was Italy and Flanders, emporiums of the late medieval bourgeoisie linked by the commercial routes of Western Europe, which stood out in both cultural movements (Humanism and the Renaissance), should not be a coincidence. The national monarchies most appropriate to the Old Regime model follow them by diffusion, and even driven by the opportunity for legitimization that the patronage of the artistic and intellectual vanguard, and the architectural programs, provide the thriving monarchies. Clergy and nobility are not left behind by emulation. The social role of the artist evolves from the guild anonymity of the Middle Ages to the pseudo-divinization of Raphael. Academicization and professionalization will end up leading to the independence of the artist, with a greater or lesser bohemian aura, who can trust a market for his production, freed from commissions, in a process that is not completed until the century XIX

After the rupture and relocation caused by the Protestant Reformation and the Catholic Counter-Reformation, Mannerism and Baroque were successively the artistic styles that spread from Italy to all of Europe from the mid-16th and 17th centuries. To a greater or lesser extent they put themselves at the service of ideology and the ruling classes, although there will also be bourgeois art where the bourgeoisie is, like Holland.

After the crisis of European consciousness at the end of the XVII century that paves the way for Modern Science that follows the Newtonian paradigm and encyclopedism; In the 18th century culture was torn between maintaining the monopoly of the Church, and the principles of Sapere aude Kantian representing the Enlightenment. From the cultural lethargy of Spain in the first half of the 18th century, it can be shown that the professor of mathematics at the University of Salamanca is as extravagant a character as the visionary Diego de Torres Villarroel. The isolation (when not the ignorance) of the European currents predominates, with the exception of the novatores or isolated figures such as Feijoo or the Marquis of Mondéjar. Enlightenment attempts at modernization are important in the last decades of the century, promoted by Carlos III and Carlos IV, and spread to America, which happens to be "rediscovered" intellectually (measurements by Jorge Juan and Antonio de Ulloa, naturalist expeditions by Cavanilles and Humboldt, and the first modern medical program, which was vaccination against smallpox) just at the moment when the American consciousness that will lead to the emancipatory movement is emerging internally.

Late Baroque and Rococo are the artistic styles of the early XVIII century, still maintaining the dominant ideology of the privileged classes; Neoclassicism and Preromanticism those of its end, open to the new reality.

In addition to the triumph of rationalist aesthetics and academic technique, discrediting Baroque sensory excesses, Neoclassicism is driven by the discovery of the ruins of Pompeii and its spread throughout Europe (to which the fashion for the Grand Tour, or rising aristocratic tourism), which coincides in time with solvent intellectual events for the Old Regime: the start of the publication of the Encyclopédie (1751) or Voltaire's reflections on the Lisbon earthquake (1755); the fashion in Europe and America is to find the sober virtues of republican Rome (rather than the decadent imperial one): the election of Cincinnatus is a good example (the paterfamilias model who abandoned his oxen to attend the call of public service as a dictator temporary and that, when his term of office is over, he returns to his plow) to name Cincinnati, a newly created city in the nascent United States. Benjamin Franklin, ambassador to France, witnessed the decadent court at Versailles sympathize with the fledgling Republic with a mixture of condescension and admiration for what it imagines (and imagines themselves) a mixture of noble savage and New Rome..

On the other hand, the pre-romantic aesthetic of Sturm und Drang, the taciturn youthful model of Goethe's Werther or the Gloomy Nights of José Cadalso presage a troubled era, in which the insoluble contradictions of The Enlightenment, which cannot reconcile the Old Regime with the emerging forces of the Revolution, will be resolved violently: the dream of reason produces monsters, as Goya so brilliantly expressed.

|

![Universidad de Salamanca, la más prestigiosa de las españolas. Más que por su contribución al aumento del saber (anclado en el neoescolasticismo), le dieron fama las espectaculares disputas entre estudiantes y órdenes religiosas que controlaban los distintos colegios. Los intentos ilustrados por reformarla (Meléndez Valdés) fueron inútiles.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/3/30/University_of_Salamanca.jpg/209px-University_of_Salamanca.jpg)