Offer and demand

The law of supply and demand is a basic economic model postulated for the formation of market prices of goods born from the neoclassical school, used to explain a wide variety of phenomena and processes both macro and microeconomic. In addition, it serves as a basis for other economic theories and models.

Basic formulation

The model in its simplest version is based on the relationship between the price of a good and its sales, and assumes that in a perfectly competitive market, the market price will settle at a point —called price equilibrium point— at which the market is cleared, that is, everything produced is sold and there is no unsatisfied demand. The supply and demand postulate implies three laws:

- When, at current price, demand exceeds supply, the price increases. Conversely, when supply exceeds demand, it decreases the price.

- An increase in price, decreases demand sooner or later and increases supply. Conversely, a decrease in price, increases demand sooner or later and decreases supply.

- The price tends to the level at which the demand equals the supply.

In economics, the model is often used in conjunction with Walrasian trial and error.

Naturally, when some of the assumptions fail, the observed and predicted behavior are somewhat discrepant, more complicated versions of the model have been attempted, substituting the basic assumptions for other logically less restrictive assumptions, but in such cases the model can become notoriously more complicated. As it happens in the theory of oligopoly, for example.

Model Origins

Although the model is generally attributed to Alfred Marshall (because that author formalized, analyzed and extended its application), the origin of the concept is earlier. The expression "offer" and "demand" it was coined by James Steuart Denham in his work A Study of the Principles of Political Economy, published in 1767. Adam Smith used this phrase in his 1776 book The Wealth of Nations, and David Ricardo, in his book Principles of Political Economy and Taxation of 1817, titled a chapter "Influence of demand and supply on price". It was explained in 1730 by the Irish economist Richard Cantillon, in his Essay on the nature of trade in general in chapter II of the second part.

In The Wealth of Nations, Smith generally assumes that demand is relatively fixed in the short and medium term (ultimately depending on the number of people), and that, consequently, it is only supply that makes make the price go up or down. It should be remembered that in those days the companies were small, and each one could only contribute fractionally to satisfy the demand. This, together with the existence of free competition, caused market prices to decrease as much as possible, tending to the cost of production, which, in turn, depends on technical considerations, not on demand.

David Ricardo goes even further by stating: «No matter how abundant the demand is, it can never permanently raise the price of a commodity over the costs of its production, including in that cost the profit of the producers. It therefore seems natural to look for the cause of the permanent price variation in production costs. Lower those and (the price of) the merchandise must eventually fall, raise them and they will surely rise. What does all that have to do with the lawsuit?

During the last years of the 19th century the marginal school of thought emerged. This field was pioneered by Stanley Jevons, Carl Menger, and Léon Walras. The main idea is that the price was established based on demand: consumers only pay what they consider adequate for the perceived utility they will receive from the goods, whatever the cost of production. This was a substantial departure from Adam Smith's ideas on determining the selling price.

This model was later criticized by Alfred Marshall in his Principles of Economics. Marshall re-introduces to the marginalist vision, through the metaphor known as Marshall's scissors, the consideration of the effect of the offer, formalizing the model of supply and demand.

We could with the same wisdom discuss whether it is the top sheet or the bottom of a scissor that cuts a piece of paper that if the value is controlled by the utility or by the cost of production.

Since the late 19th century, this theory of supply and demand has remained virtually unshakable. Most of the subsequent studies have focused on seeking to adapt the model to more real situations, incorporating aspects such as transaction costs, bounded rationality or even the principle of non-rationality, etc. based on the perception that it is the case that the real market situation corresponds to one of imperfect competition.

For example – from the early decades of the 20th century – a variety of authors, such as Joan Robinson, Edward Hastings Chamberlin; Heinrich Freiherr von Stackelberg, Jan Tinbergen, Wassily Leontief, etc., introduced a series of adjustments or partial modifications to Marshall's formalization. (see oligopoly and oligopsony, Theory of Monopolistic Competition, Stackelberg Competition; Spider Web Theorem, etc.)

Fundamental theory

The model states that in a free market, the quantity of products supplied by producers and the quantity of products demanded by consumers depend on the market price of the product.

The law of supply indicates that the supply is directly proportional to the price; the higher the price of the product, the more units will be offered for sale. On the contrary, the law of demand indicates that demand is inversely proportional to price; the higher the price, the less consumers will demand. Therefore, supply and demand make the price of the good vary.

According to the law of supply and demand, and assuming that perfect competition, the price of a good is located at the intersection of the supply and demand curves. If the price of a good is too low and consumers demand more than what producers can put on the market, there is a situation of scarcity, and therefore consumers will be willing to pay more. Producers will raise prices until the level is reached at which consumers are not willing to buy more if the price continues to rise. In the reverse situation, if the price of a good is too high and consumers are not willing to pay it, the tendency will be for the price to fall, until it reaches the level at which consumers accept the price and everything can be sold. what is produced.

The Supply Curve

The second law enunciated (see II above) establishes that, given an increase in the price of a good, and assuming a competitive market, the quantity offered of that good will be greater; that is, the producers of goods and services will increase production. This is generally referred to as the "Law of Supply".

The above is conceptualized in the supply curve, which is the graphical representation of the relationship –or elasticity– existing between the price of a good and the quantity supplied of it.

The slope of this curve determines how the quantity supplied of a good increases or decreases with a decrease or increase in its price. Price elasticity of supply is the degree of variation in the quantity supplied to a change in price. This ranges from a fully inelastic response (vertical line) meaning output does not respond to price changes to a fully elastic response (horizontal line), meaning changes in output are greater than price changes.

The determinants of this elasticity include: ease or not of acquiring inputs. Existence or not of excessive production capacity and/or accumulated inventories. Complexity of the production process, or relative difficulty of implementing extensions or modifications to that process, including the time and cost necessary to implement those modifications. More general considerations about the position of the company in relation to the market, including possible convenience of simply taking advantage of the price increase, etc.

Because supply is proportional to price, supply curves are usually, but not always, increasing.

In addition, and due to the law of diminishing returns, the slope of a supply curve may be decreasing (that is, it is usually a concave function), but not necessarily. An example is the labor market supply curve. Generally, when a worker's wage increases, he is willing to offer more hours of work, because a higher wage increases the marginal utility of work (and increases the opportunity cost of not working). But when said remuneration reaches certain levels, the worker can experience the law of diminishing returns in relation to his pay. The amount of money he is earning will make another raise of little value to him. Therefore, from that point on he could dedicate fewer hours to work as the salary increases, deciding to invest his time in leisure. We find an example of this in the salaries of the members of the Board of Directors. While it is relatively easy to motivate blue-collar or professional workers to work overtime, it is difficult to motivate the members of such councils, whose "working hours" generally range from one meeting (morning or afternoon) once a month to five or six, or even once or twice a year with salaries ranging from, for small businesses, “retention salary” of $5,000 to $10,000 per year and “attendance bonuses” of $500 to $2,000 for each meeting held attend, plus "reimbursement" for "travel expenses" etc, at salaries such as £250,000 a year (the lowest among directors of the Barclays banking group), which, however, is increased for "performance related pay" at £10.7m a year, that's not counting a variety of "achievement bonuses", "options" 3. 4; of shares, etc. It is easy to see how remuneration at that level does not produce the necessary motivation to perform duties with due attention, which ended in the economic crisis of 2008-2011.

This type of supply curve has also been observed in other markets, such as oil: after the record price caused by the 1973 crisis, the US decreased its oil production.

The Demand Curve

The demand curve represents the relationship between the quantity of a good or set of goods and services that consumers want and are willing to buy in relation to its price, assuming that the rest of the factors remain constant. The demand curve is generally decreasing, that is, at a higher price, consumers will buy less. This is generally known as the "law of demand".

The determinants of an individual's demand are the price of the good, the level of income, personal tastes, the price of substitute goods, and the price of complementary goods.

The slope and shape of the demand curve represents the price elasticity of demand, with extremes on a vertical line (inelastic demand, representing the case in which the change in demand is less than the change in prices) and a horizontal line, or elastic demand, with changes in demand greater than changes in prices (for example, in a perfectly competitive market, a price increase by a firm may lead to that firm losing all its sales).

As stated before, the demand curve is almost always downward. But there are some examples of goods that have rising demand curves. A good whose demand curve is rising is known as either a Veblen good or a luxury good; or as a Giffen good or an inferior good. The classic example of the latter, provided by Alfred Marshall, are basic foods, whose demand is defined by poverty, which does not allow its consumers to consume better quality food. As the prices of either food or general prices increase, consumers cannot afford to purchase other types of food, so they have to increase their consumption of staple foods.

Changes in Demand and Quantity Demanded

The price of a product in the market is determined by a balance between supply (what is willing to produce at a given price) and demand (what is desired to buy at a given price). The graph shows an increase in demand from D1 to D2, causing an increase in the relative price and quantity produced.

The more people want something, the quantity demanded at all prices will tend to increase. This is an increase in demand. Increasing demand can be represented on the graph as the curve to the right, because at each price point, a greater quantity is demanded.

This increase in demand causes the initial curve D1 to shift to the new curve D2. This raises the equilibrium price from P1 to P2. This raises the equilibrium quantity from Q1 to Q2. Conversely, if the demand decreases, the opposite happens, it goes from curve D2 to D1. The demand is what the consumer wants, when demand increases, prices increase. EJ: the demand for ice cream on an ordinary day can be 40 units, but on a hot day the demand for ice cream can be 100, this is because there are more people who want to consume ice cream due to the heat, even when the price of ice cream has not changed. But as the demand for ice cream increases, it is most likely that its price will rise.

The quantity demanded is what you are willing to consume at a given price. EX: if you have 30 dollars and the ice cream is worth 15 dollars, the quantity demanded at that price will be two ice creams, but, if the price of ice cream decreases to 10 dollars now there will be an increase in the quantity demanded since now three ice creams can be consumed (one more than before): the quantity demanded increased because the price decreased.

Summarizing: if demand increases, prices rise and, therefore, the quantity demanded increases. Conversely, if demand decreases, prices decrease and the quantity demanded decreases.

Example: supply and demand in a 6-person economy

The supply and demand model can be studied by individuals interacting in a market. Assume a simplified economy in which the following six individuals participate:

- Alicia is willing to pay 10 euros for a room.

- Fernando is willing to pay 20 euros for a room.

- Cristina is willing to pay 30 euros for a room.

- Our company is willing to offer a room for 5 euros

- Hotels Place is willing to offer a room for 15 euros

- Master Hotels is willing to offer a room for 25 euros.

There are many possible transactions that would please both parties, but not all of them will happen. For example, Place and Master hotels would be interested in doing their business at any price between 25 and 30. If the price was higher than 30, Cristina would not be interested, since it is too high a price. If the price dropped below 25, then it would be Master Hotels that would not be happy with the transaction. However, Cristina will discover that there are other producers in the market who are willing to sell below 25, so she will not negotiate with Fernando. In an efficient market, each seller will receive the highest possible price, and each buyer will pay the lowest possible price.

Imagine that Cristina and Master hotels are arguing about the price. Master Hotels offers a rental for 25. Before Cristina accepts it, Place Hotels offers it for 24. Fernando is not willing to sell at 24, so he withdraws. At that moment, our company is offering for 12. Place is obviously not going to sell at that price, so it seems that the sale is decided. However, Fernando appears and offers 14, but only one person is willing to sell at that price (our company). Cristina finds out and since she does not want to lose this great opportunity, she offers our company 16 per room. Now Place is also willing to sell, so we have two buyers and two sellers at that price (note that any price between 15 and 20 could have been set). Here it seems that all four agree. But what about Master and Alicia Hotels? Both are not willing to negotiate with each other, because Alicia is only willing to pay 10 and Master hotels does not want to accept anything below 25. Alicia cannot improve the offers of Fernando and Cristina to buy from our company, with which Alicia can't negotiate with them. Master cannot lower the sale price as much as our company or Place hotels, so now he can no longer negotiate with Cristina. In other words, a break-even point has been reached.

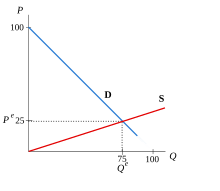

A graph of supply and demand curves can be drawn from this data.

The demand would be:

- A person is willing to pay 30 euros (Christina).

- Two people are willing to pay 20 euros (Christina and Fernando).

- Three people are willing to pay 10 euros (Christina, Fernando and Alicia).

The offer would be in this case:

- A person is willing to rent for 5 euros (our company).

- Two people are willing to rent for 15 euros (our company and hotels Place).

- Three people are willing to rent for 25 euros (our company, hotels Place and hotels Master).

Supply and demand coincide when the amount negotiated is two rooms and the price is set between 15 and 20. Whether our company sells Cristina, and Place sells Fernando, or if our company sells Fernando, and Place sells Cristina, an agreement can be reached. However the exact agreed price cannot be determined. This is the only limitation of this simplified model. If this example is transferred to a perfectly competitive market, with enough participants, then the price could be established exactly. For example, if the last trade was between someone who was willing to sell at 15.50 and someone willing to pay 15.51, then the price could be determined to within one cent. The more participants enter the market, the more likely it is that a price as close to breakeven will be found.

This simplification shows how the equilibrium price and quantity can be easily determined using an easy-to-understand situation. The results are similar to those obtained when considering that the number of participants is unlimited and other assumptions established by perfectly competitive markets.

Generalizations

- The model described above only describes a perfectly competitive market with a single product. In a real economy there are many products, some of which are complementary goods to one another, others are substitute goods to one another, etc. In addition, it is necessary to incorporate into the model the available income of consumers. In a model with n products do not exist a demand curve but should be talked about a hypersurface (2n-1)-dimensional that represents the joint demand for goods and possible sets of indifference. On the other hand they must exist n hypersurfaces that represent the offers of each of the products. All these hyper-surfaces under hypotheses similar to those raised for a product market would be intersected at a single point, which would allow to predict the prices of the n products and quantities consumed by each.

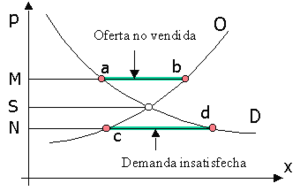

- There are models that incorporate time and assume that there is no instant adjustment of supply and demand, depending on the model prices can fluctuate but it is not clear that under any condition they converge at stable prices.

Critiques and limitations of the model

Marshall's model is based on several assumptions without which, it is suggested, it lacks validity. These assumptions can be summarized as follows:

- Existence of demand "curves". It is assumed that there is a defined demand curve that remains stable for a longer or longer period. This requires, for example, that the consumer plan in advance how they will distribute their income between different products and have stable preferences or needs. If the consumer purchases certain products only if he finds them by chance in a trade or by capricious imitation of others, then there is no planning or maximization of the utility and therefore there is no defined curve in advance. Psychological behaviors such as compulsive consumption annul the possibility of a consumer having a well-defined demand curve.

- Existence of "curves" of offer, whose deduction is basically based on average costs and marginal costs, therefore it is assumed that the offer is constrained only by the existence (cantidad) of economic resources. If production requires certain resources that may be temporarily unavailable, there are long production times or the expected demands are not accurately known, there may be temporary surpluses or shortages that in any case do not alter the price (in the short term).

- Existence of general balance, the existence of a state of economic balance or a situation very close to balance is assumed. It is assumed that there are no obstacles to the acquisition or distribution of products and it is accepted that the time factor is not important reacting the amount offered almost instantly to the amount demanded.

- Perfect knowledge, it is assumed that it is possible to obtain the economic data necessary to make the calculation required both to suggest at the theoretical level the model and to derive at the practical level suggestions of action.

- Perfect competence, a market is assumed in perfect competition, with general access to information.

- Independence of supply and demand, it is assumed that both demand and supply are independent variables.

It is very easy to give examples of markets and situations in which one or more of these assumptions are not fully or partially fulfilled. The fact that in the real world some of the necessary conditions for the supply and demand model to be valid have led to global criticism that questions the very existence of a possible law of supply and demand to which partial criticisms, that only question some of its assumptions and, consequently, adapt the application and/or extension of the model.

There are a variety of partial criticisms, which are based on the perception that the general condition of the market is not one of perfect competition but one of imperfect competition. Authors such as Joan Robinson and others introduced the analysis in oligopoly and oligopsion conditions, with theories and models such as the Theory of Monopolistic Competition, Stackelberg Competition and the Spider Web Theorem, etc.

In addition, there are also a variety of more general criticisms. Thus, for example, the positivist philosopher and sociologist Émile Durkheim, in his book 'The rules of the sociological method', in chapter three, talks about the creation of laws in the social sciences and criticizes the empirical scope that has been given to the law of supply and demand. Durkheim goes so far as to suggest that supply and demand is invalid since "the celebrated law of supply and demand has never been established inductively as a expression of economic reality.

Another approach that questions the validity of the proposal comes from the Austrian school. From this point of view it has been written: “For Mises, and in accordance with the quote that heads this article, the construction of Economic Science based on the equilibrium model and in which all the relevant information is assumed does not make sense. to construct the corresponding supply and demand functions is considered "given". and "for the Austrians in economics, and unlike what happens in the world of physics and natural sciences, there are no functional relationships (nor, therefore, functions of supply, or demand, or costs, or any other type).

From an economic point of view, Piero Sraffa (1926) criticized the inconsistency (except in exceptional circumstances, such as perfect competition) of the suggestion of an economic equilibrium and the logic that leads to the suggestion that the curve supply would be upward-sloping in a market for consumer goods. This criticism is still considered valid from the point of view of economic logic. Paul Samuelson, reviewing the arguments, notes:

- What a modernized or simplified version of Piero Sraffa's argument (1926) establishes is how almost totally empty are all categories (boxes, in the original) of Marshall's partial balance. For a logical purist of the Wittgenstein and Sraffa class, the category of the Marshallian partial balance of constant costs is even more empty than the category of incremental costs.

The central point of this critique can be summed up as follows: In the “standard” (Marshallian) model of supply and demand, the supply and demand lines intersect and intersect at a single point. However the Sonnenschein-Mantel-Debreu Theorem shows that this is not necessarily the issue. It further follows that the model of supply and demand itself cannot be rigorously derived from the general model of economic equilibrium.

However, Goodwin, Nelson, Ackerman and Weissskopf suggest that: “It is important not to place too much trust in seemingly accurate licorice supply and demand charts. Supply and demand analysis is a useful and accurate conceptual tool that smart people have created to help us gain an abstract understanding of a complex world. It does not give us - and should not be expected to give us - in addition a complete and faithful description of any real world market."

A possible alternative model of market pricing is found in Walrasian trial and error, which, unlike supply and demand, easily accommodates a range of prices.

Business supply and demand

The company's offer

The second constitutive element of pricing is the supply of a good. Supply is the amount of an economic good that producers will put on the market (given the price level and their production costs). In the same logic of demand, it can be assumed that producers will offer more or less quantity of product depending on its price: at a higher price they will offer more quantity and less at a lower price.

The elasticity of supply indicates the degree of response of the quantity supplied to changes in price. Its most significant determining factor is time, of which three variants are established:

- In the short term, the company will not be able to react by increasing its production in the face of rising prices, as it will normally not have the necessary resources.

- In the medium term, it may not be able to modify its dimension, but it will achieve a more intensive use of available resources.

- In the long term you can modify your dimension, which will allow you to respond with greater productions to price increases.

Consequently, the longer the period of time, the greater the elasticity of supply.

In addition to the price, there are other factors that influence the quantity supplied: the prices of the productive factors, the production costs, the technological level, the existence of substitute products, the organization of the market, etc.

The company's demand

The concept of demand expresses what quantities of a good a consumer is willing to buy at different prices. In general terms it can be established that, at a lower price, the quantity demanded will increase.

There are two exceptions to this assumption: basic necessities, whose demand will be affected very little by the price increase, and luxury goods, which are demanded regardless of their price. It can be affirmed that, for normal goods, the quantity demanded has a specific relationship with its price: it increases when the price decreases, and decreases when the price increases.

Elasticity of Demand

The quantity demanded of a good does not always respond in the same way to changes in prices. In some cases, a small change in price leads to a significant change in the quantity demanded, while in other cases it hardly affects it.

The concept of price elasticity of demand refers to the sensitivity of the quantity demanded to variations in price. Consequently, demand is elastic if a percentage change in price leads to a larger percentage change in quantity demanded, inelastic if smaller, and unitary when both are equal.

The demand line in graph 2 is very elastic, since, as expressed graphically, a slight increase in price (from p' to p'') leads to a significant decrease in demand (from q ' to q'').

On the contrary, the demand line B is highly inelastic, since the same increase in price barely changes the quantity demanded.

The price elasticity of demand depends on the following circumstances:

- The kind of good it's about. A good of first need will have a very unelastic demand.

- Of the existence of substitute goods. The existence of many other similar goods will make the demand more elastic regarding its price.

- Of the part that represents the consumption of a good in the total income: the demand for a good will be more elastic the greater its share in the rent.

- Of the elasticity-price of demand, which is not equal in all points of the right of demand, but depends on the nature of the good.

- From the time considered: the greater this, the greater the response of the amount demanded to the changes in the price.

The quantity demanded of a certain good does not depend solely on its price. Other factors that condition it must be taken into account, such as the price of other goods, the income and wealth of the consumer, the tastes and fashions that affect their desires, consumption habits and many other circumstantial or subjective factors of a different nature..

Contenido relacionado

Italian lira

Partial equilibrium

Ecuadorian sucre