Novgorod Republic

The Novgorod Republic medieval that occupied territories of present-day Russia, from the Baltic Sea to the Ural Mountains, between the 12th and 15th centuries. Its capital was the eponymous city of Novgorod.

Origins

Novgorod served as the original capital of the Rus people until 882, when Oleg transferred its administration to kyiv. From this date until 1019-1020, Novgorod was part of Kievan Rus'. The princes of Novgorod were appointed by the Grand Prince of kyiv (usually one of his eldest sons). Novgorod was a kind of spiritual center due to the legend of having been the first city of Rus, and it still has the relics of the traditional beliefs that preceded Christianity and that today are part of forgotten history.

Novgorod continually played an important role in the politics of Rus. He assisted Vladimir I of kyiv, and was later instrumental in the accession of Yaroslav I the Wise. Therefore, one of his first actions was to guarantee the loyal Novgorodians numerous freedoms and privileges, which laid the foundations for the future Novgorod Republic. While still part of Kievan Rus', Novgorod became a powerful, largely independent regional centre, as the city had a more participatory government than the rest of Rus', and could elect its local officials. Even so, it was a very important part of the political and cultural panorama of Kievan Rus.

The tendencies of Novgorod to separate from Kievan Rus were manifested in the first half of the 11th century. The boyars of Novgorod were the main promoters of the separation, with the support of the urban population who had to pay tribute to kyiv and equip the troops for their military campaigns. In the early years of the 12th century, Novgorod began to invite different Knyaz (princes) to govern the city without seeking advice or confirmation from the Prince of Kiev. In 1136, the boyars and leading merchants gained political independence by dismissing Prince Vsevolod of Pskov, and over the next century and a half they were able to invite and dismiss numerous princes, although these actions were based on who was the dominant prince. of the Rus, and not in an idea of independence on the part of Novgorod.

Cities such as Staraya Russa, Staraya Ladoga, Torzhok and Oreshek were placed under the rule of Novgorod. The city of Pskov was part of the Novgorod Republic in the 12th century although it began to claim its independence in the middle of the < century. span style="font-variant:small-caps;text-transform:lowercase">XIII. The independence of Pskov was recognized by the Treaty of Bolotovo in 1348. Between the 12th and 15th centuries the Novgorod Republic expanded to the east and northeast. The Novgorodians explored the areas of Lake Onega, the Northern Dvina River, and the coasts of the White Sea. The Ugric tribes, who inhabited the northern Urals, had to pay tribute to Novgorod. The lands north of the city, rich in furs, marine fauna and salt mines, were of great economic importance for the Novgorod Republic.

Government

The precise constitution of the medieval Novgorod Republic is uncertain, although traditional history has created the image of a highly institutionalized network of veches (public assemblies), and a government of posadniks (mayors), týsiatski (originally, the chief of the citizen militia, but later, a judicial and commercial official), other members of aristocratic families, and the archbishop of Novgorod.

Some scholars argue that the archbishop was the head of the executive branch of the government, although it is difficult to determine the exact powers of the officials. It is possible that there was a "Council of Lords" (Совет Господ), chaired by the archbishop, which would meet in the episcopal palace (from 1433, in the Palace of Facets), but more recently, Jonas Granberg has questioned whether such a body actually existed; he argues that it is, in fact, an invention of historians who have read too many scattered sources.

The executives (at least nominal) of Novgorod were always the princes, invited by Novgorodians from neighboring states, although their power is believed to have faded in the century XIII and the beginning of the XIV century. It is not clear whether the archbishop of Novgorod was the true head of state or the executive head of the Republic, but in any case, he was an important city official; In addition to supervising the Church in Novgorod, they headed embassies, supervised certain court cases of a secular nature, and carried out other secular tasks, but the archbishops seem to have worked with the boyars to reach a consensus, and almost never acted alone. The archbishop was not appointed, but elected by the Novgorodians, and approved by the metropolitan bishop of Russia.

Another important executive was the posádnik, who presided over the veche, co-chaired the courts, along with the Prince, supervised the collection of taxes, and managed the current affairs of the city. Most of the Prince's important decisions had to be approved by the posadnik. In the middle of the 14th century, instead of one posadnik, the veche began to choose six. These six posadniks retained their status for life, and each year they elected a posadnik chief from among them.

The exact composition of the veche is also uncertain, although it appears to have comprised both members of the urban and rural populations. Whether it was a democratic institution or controlled by boyars has been the subject of debate. Posadniks, týsiatskis, and even bishops and archbishops of Novgorod were often elected, or at least approved by the veche.

External relations

The Republic fought against Swedish expansion and German feudalism. Since the middle of the 12th century, the Swedes were invading the Finnish lands in which some populations had to pay tribute to Novgorod. Novgorod went to war with the Swedes twenty-six times and with the Livonian Brothers of the Sword eleven times. It also competed with the Principality of Vladimir-Suzdal for hegemony in northern Rus. Taking advantage of the Mongol invasion of Kievan Rus, the Knights of the Teutonic Order, allied with Danes and Swedes, began to attack the Novgorod territories in 1240. Their campaigns failed with the Battle of the Neva in 1240 and the Battle of Lake Peipus in 1242..

On August 12, 1323, the Treaty of Nöteborg was signed between Sweden and Novgorod, regulating the borders. This was the first treaty between the future Russia and the kingdom of Sweden.

The Republic managed to avoid the invasion of the Golden Horde, although it had to pay tribute to it until Moscow principalities were created to serve as containment.

Fall

Tver, Moscow, and Lithuania (later the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth) tried to subjugate the Republic since the 14th century.

Upon becoming Grand Prince of Vladimir, Mikhail Yaroslavich, being prince of the Principality of Tver, sent his rulers to Novgorod without prior authorization from the citizens. This incident pushed Novgorod to strengthen its ties with Moscow. Ivan I, Simeon I and other great Moscow princes tried to limit the independence of Novgorod. This is how a serious conflict broke out in 1397, when Moscow annexed the lands along the Northern Dvina River - although in 1398 this territory was returned to Novgorod.

Faced with the Moscow advance, the majority of the boyars advocated unification with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. This group was called the “Lithuanian party”, and was led by Marfa Borétskaya, widow of posádnik (mayor) Isaac Boretsky. On the initiative of this party, the city authorities invited Prince Mikhail Olekovich and proposed that he marry Marfa Boretskaya and lead the Republic. The Novgorod government also made an alliance with Casimir IV Jagiellon, Grand Duke of Lithuania. The prospect of a new alliance, with the United Kingdom of Poland and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, caused great shock among the people of the republic. The Moscow authorities tried to take advantage of the discord within the Republic and declared war. The Moscow army won a decisive victory at the Battle of Shelon (1471), although Novgorod was able to maintain limited formal independence for 7 more years. In 1478, Ivan III sent his army to besiege Novgorod: the siege ended with a massacre of the population and the destruction of the veche (popular assembly) including its library and archives. The bell with which the veche was called, the symbol of Novgorod independence, was taken to Moscow. This event is considered the final act of the Novgorod Republic.

Economy

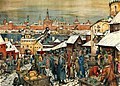

by Apollinary Vasnetsov.

The economy of the Novgorod Republic included agriculture and animal husbandry (for example, the archbishops of Novgorod and others bred horses for the Novgorod army), while hunting, beekeeping and fishing were also widespread.. In most regions of the republic, these different "industries" They were combined with agriculture. Iron was mined on the coast of the Gulf of Finland. Staraya Russa and other localities were known for their salt pans. The cultivation of flax and hops was also of great importance. Farm products, such as furs, beeswax, honey, fish, lard, flax, and hops, were sold on the market and exported to other Russian cities or abroad.

However, Novgorod's true wealth came from the fur trade. The city was the main contact point for trade between Russia and northwestern Europe, as it was located at the eastern end of the Baltic trade network established by the Hanseatic League. From the northeastern lands of Novgorod ('The Lands Beyond the Havens', as they were called in the chronicles), the area that extended north of lakes Ladoga and Onega to the White Sea and east to the Ural Mountains had so many furs that medieval travel accounts speak of furry animals raining from the sky. Novgorod merchants traded with Swedish, German and Danish cities. In the early years, the Novgorodians themselves sailed the Baltic (several incidents with Novgorod merchants in Gotland and Denmark are recounted in the First Novgorod Chronicle). Orthodox churches of Novgorodian merchants have been excavated on Gotland. Likewise, the Gotland merchants had their own church of St. Olaf and trading house in Novgorod. However, the Hanseatic League contested the right of Novgorod merchants to carry out maritime trade independently and to deliver cargoes to Western European ports with their own ships. From Western Europe they imported silver, cloth, wine and herring.

Foreign coins and silver were used as currency before Novgorod began minting its own novgorodka coins in 1420.

Society

In the 14th and 15th centuries, more than half of Novgorod's privately owned lands were in the hands of about 30-40 noble boyar families. These vast estates served as material resources, which ensured the political supremacy of the boyars. The House of Holy Wisdom (Дом святой Софии, Dom Svyatoy Sofiy) - the main ecclesiastical establishment of Novgorod - was its main rival in terms of land ownership. Their votchina were located in the most economically developed regions of the Novgorod region. It is known that the Yuriev Monastery, the Arkazhsky Monastery, the Antoniev Monastery and some other privileged monasteries were large landowners. There were also the so-called zhityi lyudi (житьи люди), who owned less land than the boyars, and small unprivileged votchina owners called svoyezemtsy (своеземцы, or private landowners). The most common form of labor exploitation – the metayage system – was typical of the aforementioned categories of landowners. Their domestic economies were largely staffed by slaves (kholopy), whose numbers had been steadily declining. Along with metayage, monetary payments also gained significant importance in the second half of the 15th century.

Some scholars maintain that feudal lords attempted to legally tie peasants to their land. Certain categories of feudally dependent peasants, such as davniye lyudi (давние люди), polovniki (половники), poruchniki'] (поручники), dolzhniki' (должники), were deprived of the right to abandon their masters. Boyars and monasteries also tried to restrict other categories of peasants from changing feudal lords. However, until the end of the 16th century, peasants could leave their land in the weeks before and after St. George's Day in the fall.

Marxist scholars (e.g. Aleksandr Khoroshev) often spoke of the class struggle in Novgorod. About 80 major uprisings occurred in the republic, which often turned into armed rebellions. The most notable ones occurred in 1136, 1207, 1228-29, 1270, 1418 and 1446-47. The degree to which they were based on class struggle varied greatly. It is unclear to what extent they were based on "class struggle". Many occurred between various factions of boyars or, if peasants or merchants participated in a revolt against the boyars, it was not that the peasants wanted to overthrow the existing social order, but more often than not it was a demand for better government. by the ruling class. There seemed to be no idea of abolishing the office of prince or allowing peasants to run the city.

During the entire Republican period, the Archbishop of Novgorod was the head of the Orthodox Church. The population of the Novgorod lands became Christian. The Strigolniki sect spread to Novgorod from Pskov in the middle of the 14th century, and its members renounced the ecclesiastical hierarchy, to monasticism and to the sacraments of the priesthood, communion, repentance and baptism. In the second half of the XV century, another sect appeared in Novgorod, called by its opponents the heresy of the Judaizers, which later told with the support of the Moscow court.

Images

Kremlin of Novgorod

Novgorod Market (with the Kremlin at the bottom) painted by Apollinari Vasnetsov

Silver coins of Novgorod, 1420-1478