Novel

A novel (from the Italian novella) is a literary work in which a feigned action is narrated in whole or in part and whose purpose is to cause aesthetic pleasure to the viewers. readers with the description or painting of interesting events or sets as well as characters, passions and customs, which in many cases serve as inputs for their own reflection or introspection. The twenty-third edition of the Dictionary of the Spanish language of the Royal Spanish Academy defines it more generally as a "narrative literary work of a certain length" and as a "narrative literary genre that, with precedent in Greco-Roman Antiquity develops from the Modern Age". The novel is distinguished by its open nature and its ability to contain diverse elements in a complex story. This open nature offers the author great freedom to integrate characters, introduce intersecting or subordinate stories to one another, present events in a different order from that in which they occurred, or include texts of a different nature in the story: letters, administrative documents, legends, poems, etc. All this gives the novel greater complexity than that presented by the other narrative subgenres.

Features

The characteristics that allow us to differentiate a novel from another literary genre are the following:

- Narras real or fictitious facts.

- Predominates the narrative, although it includes: description, dialogue, interior monologue or epistole.

- It describes the environment where the narrative develops.

- The novel is written in the form of prose.

- Take care of the aesthetics of words.

- The development of characters is deeper than in a story or story.

- An extensive narrative: novels usually have between 50 000 and 200 000 words, or 150 to 1200 pages or more.

Here lies the difference with the story and the story. There is a diffuse area between the short story and the novel that cannot be clearly separated. The term nouvelle or short novella is sometimes used to designate texts that seem too short to be novel and too long to be story; but this does not mean that there is a third gender (on the contrary, it would double the problem because then there would be two limits to define instead of one).

Purpose

Depending on the object of the narrative, it can have two very specific purposes.

- Disseminate the experiences, concerns and ideas of the author in order to influence some way in the society to which he is directed.

- Disseminate customs, way of life and the aspirations of a particular social group.

Essentials

- The action: It is the narrative of events that happen in history:

- The introduction: It is the initial part of the narrative where the theme is announced and initiates the development of conflicts or presents the characters with their physical and psychological characteristics. It also describes the environment.

- The knot: It is the central part of the narrative where conflicts or actions are linked to reach a maximum point.

- The outcome: This is considered to be the final part, because the conflicts or actions of the narrative after reaching a maximum point trigger actions that can be happy or unhappy, which will depend on the object raised in the narrative.

- The characters: they are the ones who develop the action:

- The main characters: They are the protagonists, those who lead the actions, and the narrative will unfold around them.

- Side characters: They are the ones who point the story of the main characters with their own stories.

- The filler, leakage or tertiary characters: They are all those who appear in the narrative with an unimportant function, and disappear.

- The environment: It is the place where the characters move. These can be:

- Physical: All the elements that make up the scene, for example: house, river, city.

- Social: Beliefs, forms of life, thoughts of an era or of a society.

- Emotional: They present moods, anguish, feelings surrounding the characters.

Expressive form

- The narration: This form of expression is predominant in the novel where this can be:

- First-person Narration: When the character narrates his own story (the protagonist is the narrator).

- Third-person Narration: The narrator tells the story (an omniscient child).

- The description: It is an expression used to describe the physical and psychological aspects of the characters.

- The dialogue: Form of expression for the characters to communicate with each other.

The language of those who speak is reflected according to their age, sex, education, social and emotional level.

- The monologue (inner conversation): It is a form of expression that consists of showing what the character thinks and does not say. Silent measurements of the character.

- The Epistle: This expression is unused, and consists of narrating events through a letter that the characters are written to each other.

Typology

The novel is the kingdom of freedom of content and form. It is a protean genre that has presented multiple forms and points of view throughout history.

To classify this genre, it must be taken into account that there are various criteria, used by the different typologies proposed:

- By the tone that keeps the work, we talk about:

- satirical novel

- humorous novel

- didactic novel

- lyric novel

- By the way:

- autobiographical

- epistolar

- dialogue

- light

- short novel or novel

- Polyphonic novel

- learning novel or Bildungsroman

- metanovela

- According to the audience to whom it arrives or the mode of distribution, it is said that:

- novel trivial

- Supersales or best seller

- novel by presentations or novel folletinesca

- According to their content, novels can be:

- adventures

- Bélica

- Byzantine

- cavalry

- cavalry books

- science fiction

- courtesan

- Costumbrist or customs: describes the environment in which they move and the everyday life forms of a particular social group: customs, typical characters. Within this type of novel, according to the style, realism and naturalism took place. It's a typical genre of the century.XIXwith authors like Balzac and Zola in France; Dickens; Gogol and Turguénev in Russia; and in Spain: Fernán Caballero, F. Trigo, Pardo Bazán, Pereda or Blasco Ibáñez.

- of spies and suspense

- fantastic.

- Crime fiction

- Gothic

- historical historical

- of mystery

- morisca

- Black

- Pastoril

- picaresque

- police

- Pink

- sentimental

- social: it diminishes as far as possible the description of individual lives, replacing them with a collectivity, because it does not matter the human being itself, but as part of a group or social class. Their attitude is critical, with the desire to denounce situations, environments and ways of life of a group. It was cultivated in Spain in the 1950s: Spanish social novel

- of terror

- Western novel or westerns

We must add to this list other typologies that take the style of the work as a criterion and then we talk about:

- realistic

- naturalist novel

- existential

- Roman courtois

Or, if their arguments are considered, one can speak of:

- psychological

- Thesis novel: It is the one that gives more importance to the author's intentions, generally ideological, than to the narrative. Very cultivated in the centuryXIXespecially by Fernán Caballero and Father Coloma

- novel testimony

From the late Victorian period to the present, some of these varieties have become veritable subgenres (science fiction, romance novels) very popular, although often ignored by critics and academics; in recent times, the best novels in certain subgenres have begun to be recognized as serious literature.

History

The novel is the latest of all literary genres. Although it has precedents in the Ancient Age, it was not established until the Middle Ages.

Precedents

There is a whole tradition of long narrative stories in verse, typical of oral traditions, such as the Sumerian (Epic of Gilgamesh) and the Hindu (Ramaiana and Mahabharata).

These epic tales in verse occurred equally in Greece (Homer) and Rome (Virgil). It is here where the first fictions in prose are found, both in their satirical modality (with The Satiricon by Petronius, the incredible stories of Luciano de Samosata and the protopicaresque work of Apuleius The Golden Ass ). Two genres appear in the Hellenistic era that would be resumed in the Renaissance and are at the origin of the modern novel: the Byzantine novel (Heliodoro de Émesa) and the pastoral novel (Dafnis and Chloe, by Longo)..

Middle Ages

The Genji Novel (Genji Monogatari), by Murasaki Shikibu, is a classic work of Japanese literature and is considered one of the oldest novels in history. history.

In the West, in the 11th centuries and XII, romances arose, which were long fictional narratives in verse, which were so called because they were written in the Romance language. They were especially dedicated to historical-legendary themes, around characters such as El Cid or the Arthurian cycle.

In the 13th century, the Mallorcan Ramon Llull wrote the first modern Western novels: Blanquerna and Felix or the Book of Wonders, as well as other short stories in prose such as the Book of Beasts.

In the XIV and XV the first prose romances arose: long narratives on the same chivalrous themes, only avoiding rhymed verse. Here is the origin of the books of chivalry. Two of the four classic Chinese novels were written in China, Luo Guanzhong's Romance of the Three Kingdoms (1330) and the first version of Shi's At the Water's Edge. Nai'an.

Along with the books of chivalry, collections of short stories arose in the XIV century, which include Boccaccio and Chaucer its most prominent representatives. They used to resort to the artifice of the "story within the story": it is not like the authors, but their characters, who tell the stories. Thus, in The Decameron, a group of Florentines flee from the plague and entertain each other by telling stories of all kinds; in the Canterbury Tales , they are pilgrims who go to Canterbury to visit the grave of Thomas Becket and each one chooses stories that relate to their state or his character. Thus the nobles tell more "romantic" stories, while the lower class prefer stories of everyday life. In this way, the true authors, Chaucer and Boccaccio, justified these stories of traps and mischief, of illicit love and clever intrigues in which they laughed at respectable professions or the inhabitants of another city.

At the end of the XV century, the sentimental novel emerged in Spain, as the latest derivation of the conventional Provencal theories of courtly love. The fundamental work of the genre was the Cárcel de amor (1492) by Diego de San Pedro.

The change from one century to another was dominated by the books of chivalry. In Valencia, this type of fictional prose spread to the Valencian language, with works such as Tirante el Blanco "Tirant lo Blanc" by Joanot Martorell (1460-1464) or the anonymous novel Curial e Güelfa (mid-15th century). The most representative work of the genre was the Amadís de Gaula (1508). This genre continued to be cultivated in the following century, with two cycles of novels: the Amadises and the Palmerines.

Modern Age

16th century

The spread of the printing press increased the commercialization of novels and romances, even though printed books were expensive. Literacy was faster in terms of reading than in terms of writing.

The entire century was dominated by the subgenre of the pastoral novel, which placed the love affair in a bucolic setting. It can be considered to have started with La Arcadia (1502), by Jacopo Sannazaro, and spread to other languages, such as Portuguese (Menina y moza, 1554, by Bernardim Ribeiro) or English (The Arcadia, 1580, from Sidney).

However, in the middle of the century, there was a change of ideas towards a greater realism, surpassing in this point the pastoral and chivalrous novels. This is seen in the Gargantua and Pantagruel by François Rabelais and in the Life of Lazarillo de Tormes and his fortunes and adversities (1554), the latter origin of the picaresque novel. Two of the four classic Chinese novels are written in the East, the second version of At the Water's Edge (1573) by Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong, and Journey to the West (1590), attributed to Wu Cheng'en.

17th century

The modern novel, as a technique and literary genre, is in the XVII century in the Spanish language, being its best example Don Quixote de la Mancha (1605) by Miguel de Cervantes. It is considered the first modern novel in the world, since it innovates with respect to the classic models of Greco-Roman literature such as the epic or the chronicle. It already incorporates an episodic structure according to a premeditated unitary fixed purpose. It began as a satire on Amadis, who had made Don Quixote lose his head. The defenders of Amadís criticized the satire because it could barely teach anything: Don Quixote neither offered a hero to emulate nor satisfied with beautiful dialogues; all he could offer is to make a mockery of noble ideals. Don Quixote was the first truly anti-Romance work of this period; Thanks to its form that demystifies the chivalric and courtly tradition, it represents the first literary work that can be classified as a novel.

After Quijote, Cervantes published the Exemplary Novels (1613). In the 17th century, a «novel» was understood as the intermediate short story between the short story and the long novel, that is, what today we call it a short novel. Cervantes' Exemplary Novels are original, they do not follow Italian models, and in the face of criticism of Don Quixote, which was said to teach nothing, they intended to offer moral behavior, an alternative to the heroic and satirical models. However, it continued to arouse criticism: Cervantes spoke of adultery, jealousy and crime. If these stories provided an example of anything, it was immoral actions. Defenders of the "novel" they responded that his stories provided good and bad examples. The reader could still feel compassion and sympathy with the victims of crimes and intrigues, if examples of evil were narrated.

Then arose in response to these dubious novels a more noble and lofty romance, with forays into the bucolic world, Honoré d'Urfé's La Astrea (1607-27) being the most famous. These romances were criticized for their lack of realism, to which their defenders replied that they were really "novels in code" (roman à clef), in which, covertly, references were made to characters from the real world. This is the line that Madeleine de Scudéry followed, with plots set in the ancient world, but whose content was taken from real life, her characters being, in reality, her friends from the literary circles of Paris.

Twenty years later, Madame de La Fayette took the decisive step, her best-known work being The Princess of Clèves (1678), in which she took the technique of the Spanish novel, but It suited French taste: instead of proud Spaniards dueling to avenge their reputations, it detailed the motives of its characters and human behavior. It was a "novel" about a virtuous lady, who had the opportunity to risk illicit love and not only resisted her temptation, but she increased her unhappiness by confessing her feelings to her husband. The melancholy that her story created was entirely new and sensational.

At the end of the XVII century, little French novels were written and distributed, especially in France, Germany and Great Britain, which they cultivated scandal. The authors maintained that the stories were true and were told not to shock, but to provide moral lessons. To prove it, they gave their characters fictitious names and told the stories as if they were novels. Collections of letters also arose, which included these comics, and which led to the development of the epistolary novel.

It is then that the first "novelas" English originals, thanks to Aphra Behn and William Congreve.

18th century

The cultivation of the scandalous novel gave rise to various criticisms. They wanted to overcome this genre by returning to «romance», as understood by authors such as François Fénelon, famous for his work Telemachus (1699/1700). Thus a genre of so-called "new romance" was born. Fénelon's English publishers, however, avoided the term "romance", preferring to publish it as "new prose epic" (hence the prefaces).

Novels and romances from the early 18th century were not considered part of "literature", but yet another item to trade with. The center of this market was dominated by fiction that claimed to be fiction and read as such. They comprised a large production of romances and, at the end, an opposite production of satirical romances. At the core, the novel had grown, with stories that were neither heroic nor predominantly satirical, but realistic, short, and thought-provoking with their examples of human behavior.

However, there were also two extremes. On the one hand, books that purported to be romances, but were really anything but fictional. Delarivier Manley wrote the most famous of these, her New Atalantis, filled with stories the author claimed she had made up. The censors were helpless: Manley was selling stories that discredited the Whigs in power, but that supposedly took place on a fantasy island called Atalantis, which prevented them from suing the author for libel unless they could prove that was the case. In England. Private stories appeared in the same market, creating a different genre of personal love and public battles over lost reputations.

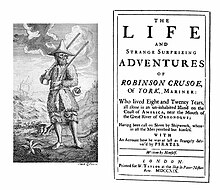

Conversely, other novels argued that they were strictly nonfiction, but read like novels. This is the case with Robinson Crusoe by Daniel Defoe, in whose preface he states:

If ever the story of a particular man in the world deserved to be made public, and to be accepted when published, the editor of this story believes it will be this.

(...) The editor believes it is a fair story of facts; there is no appearance of fiction in it...[1]

This work already warned on its cover that it was not a novel or a romance, but a story. However, the page layout was too reminiscent of the "new romance" with which Fénelon had become famous. And certainly, as the term was understood at the time, this work is anything but a novel. It was not a short story, nor did it focus on intrigue, nor was it told in favor of a well-cut ending. Nor is Crusoe the anti-hero of a satirical romance, despite speaking in the first person singular and having encountered all kinds of miseries. Crusoe doesn't really invite laughter (although readers will, of course, be glad to take humor in his proclamations about being a real man). He is not the real author, but the pretended one who is serious, life has drawn him into the most romantic adventures: he has fallen into the clutches of pirates and survived for years on a deserted island. What's more, he has done it with exemplary heroism, being as he was a mere sailor from York. You can't blame the readers who read it as a romance, so full is the text of pure imagination. Defoe and his publisher knew that everything that was said was totally unbelievable, and yet they claimed that it was true (or, if it wasn't, it was still worth reading as a good allegory).

The publication of Robinson Crusoe, however, did not lead directly to the market reform of the mid-eighteenth century. It was published as a dubious story, so they entered the scandalous game of the 18th century market.

The reform in the English book market of the early eighteenth century came hand in hand with the production of classics. In the 1720s, a large number of classic European novel titles were republished in London, from Machiavelli to Madame de La Fayette. The "novels" by Aphra Behn had appeared together in collections, and the author of the 17th century had become a classic. Fénelon had already been one for years, just like Heliodorus. The works of Petronio and Longo appeared.

Interpretation and analysis of the classics put readers of fiction in a better position. There was a big difference between reading a romance, getting lost in an imaginary world, or reading it with a preface informing about the Greeks, Romans or Arabs who had produced titles like The Aethiopics or The Thousand and one nights (which was first published in Europe between 1704 and 1715, in French, a translation on which the English and German editions were based).

Shortly after, Gulliver's Travels (1726) appeared, a satire on Jonathan Swift, cruel and ruthless against the optimism emanating from Robinson Crusoe and his confidence in the ability of man to overcome.

"Now published for the first time to cultivate the principles of virtue and religion in the minds of the young men of both sexes, a narrative that has the basis in truth and nature; and at the same time entertains pleasantly..."

Changed the design of the covers: the new novels did not pretend to sell fiction while threatening to reveal real secrets. Nor did they appear as false "true stories". The new title would already indicate that the work was fictional, and indicated how the public should treat them. Samuel Richardson's Pamela, (1740) was one of the titles that introduced a new title format, with its formula [...], or [...] offering an example: "Pamela, or Virtue Rewarded - Now published for the first time to cultivate the principles of virtue and religion in the minds of young men and women, a narrative that is grounded in truth and nature; and at the same time it entertains pleasantly". So says the title, and makes it clear that it is a work created by an artist who intends to achieve a certain effect, but to be discussed by the critical public. Decades later, novels no longer needed to be more than novels: fiction. Richardson was the first novelist who united a moralizing intention to the sentimental form, through quite naive characters. Such candor is seen in Oliver Goldsmith's The Vicar of Wakefield (1766).

More realism is found in the work of Henry Fielding, who is influenced by both Don Quixote and by the Spanish picaresque. His best known work is Tom Jones (1749).

In the second half of the century, literary criticism became established, a critical and external discourse on poetry and fiction. The interaction between separate participants was opened with it: novelists would write to be criticized and the public would observe the interaction between critics and authors. The new criticism of the end of the XVIII century implied a change, by establishing a market for works worth discussing, while the The rest of the market would continue to exist, but would lose most of its public appeal. As a result, the market was divided into a lower camp of popular fiction and critical literary production. Only privileged works could be discussed as works created by an artist who wanted the public to discuss this and not another story.

The scandal produced by DuNoyer or Delarivier Manley disappeared from the market. It did not attract serious criticism and was lost if it remained unchallenged. It eventually needed its own brand of outrageous journalism, which developed into the tabloids. The lower market for prose fiction continued to focus on the immediate satisfaction of an audience that enjoyed their stay in the fictional world. The most sophisticated market became complex, with works playing new games.

In this high market, two traditions could be seen developing: works that played with the art of fiction—Laurence Sterne and his Tristram Shandy among them—the other closer to the discussions that prevailed and modes of their hearing. The great conflict of the XIX century, whether the artist should write to satisfy the public or to produce art for art's sake, had not yet arrived.

The French Enlightenment used the novel as an instrument of expression of philosophical ideas. Thus, Voltaire wrote the satirical tale Candide or Optimism (1759), against the optimism of certain thinkers. Shortly after, it would be Rousseau who would reflect his enthusiasm for nature and freedom in the sentimental novel Julia or the new Heloise (1761) and in the long educational novel Emile (1762).

The sentimental novel manifested itself in Germany with The Troubles of Young Werther, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (1774). Bernardin de Saint-Pierre also became popular at this time, with his novel Paul and Virginia (1787), which narrates the unhappy love between two adolescents on a tropical island.

In China, the last of the four classic novels was written at the end of the century, the Dream of the Red Mansions, also called Dream in the Red Chamber (1792) of Cao Xueqin.

Contemporary Age

19th century

At the end of the XVIII century, novels full of a melancholic sentimentality appear that open the romantic period that is fully developed in the XIX century with the appearance of the historical, psychological, poetic and social novel. The genre reaches its technical perfection with realism and naturalism. It is at this time that the novel reaches its maturity as a genre. Its form and aesthetics did not change until the XX century: its division into chapters, the use of the narrative past and an omniscient narrator.

One of the first exponents of the novel in this century is the Gothic novel. Since the beginning of the XVII century the novel had been a realistic genre as opposed to romance and its excessive fantasy. It had then turned to scandal and for this reason it had undergone its first reform in the 18th century. Over time, fiction became the most honorable field of literature. This development culminated in a wave of fantasy novels in the transition to the 19th century, in which sensitivity and women became its protagonists. It is the birth of the Gothic novel. The classic of the Gothic novel is The mysteries of Udolfo (1794), in which, as in other novels of the genre, the notion of the sublime (aesthetic theory of the XVIII) is crucial. The supernatural elements are also basic in these and the susceptibility that their heroines showed towards them ended up becoming an exaggerated hypersensitivity that was parodied by Jane Austen with Northanger Abbey (1803). Jane Austen's novel introduced a different style of writing, the 'comedy of manners'. Her novels are often not only humorous, but also scathingly critical of the restrictive, rural culture of the early XIX century . Her best known novel is Pride and Prejudice (1811).

It is also in this century when Romanticism developed, which, contrary to what one might think, did not cultivate the novelistic genre as much. Byron, Schiller, Lamartine or Leopardi preferred drama or poetry, but even so they were the first to give the novel a place within their aesthetic theories.

In France, however, pre-Romantic and Romantic authors devoted themselves more widely to the novel. One can cite Madame de Staël, Chateaubriand, Vigny (Stello, Serfdom and military greatness, Cinq-mars), Mérimée (Chronicle of the reign of Charles IX, Carmen, Double error), Musset (Confession of a Child of the Century), George Sand (Lélia, Indiana) and even Victor Hugo from (Our Lady of Paris).

In England, the romantic novel finds its maximum expression with the Brontë sisters (Emily Brontë, Charlotte Brontë and Anne Brontë) and Walter Scott, cultivator of a traditional and conservative historical novel, set in Scotland (Waverley , Rob Roy) or the Middle Ages (Ivanhoe or Quintin Durward). In the United States, Fenimore Cooper cultivated this type of novel, his best-known work being The Last of the Mohicans . In Russia, one can cite Pushkin's novel in verse, Eugene Onegin and in Italy, Los Novios by Alessandro Manzoni (1840-1842).

The works of Jean Paul and E.T.A. Hoffmann are dominated by the imagination, but they retained the heterogeneous aesthetic of the XVIII century, of Laurence Sterne and of the Gothic novel.

On the other hand, there is the realistic novel, which is characterized by the plausibility of the intrigues, which are often inspired by real events, and also by the richness of the descriptions and the psychology of the characters. The desire to build a coherent and complete novelistic world saw its culmination with Honoré de Balzac's Human Comedy, as well as with the works of Flaubert and Maupassant, and ended up evolving towards the naturalism of Zola and towards the psychological novel.

In England we find authors such as Charles Dickens, William Makepeace Thackeray, George Eliot and Anthony Trollope, in Portugal, Eça de Queiroz and in France Octave Mirbeau, who try to present a "global image" of the whole society. In Germany and Austria, the Biedermeier style prevails, a realistic novel with moralistic features (Adalbert Stifter).

This is the great century of Russian literature, which gave numerous masterpieces to the novel genre, especially in the realistic style: Anna Karenina by Leo Tolstoy (1873-1877), Fathers and sons of Ivan Turgenev (1862), Oblomov of Ivan Goncharov (1858). Also the novelistic work of Fyodor Dostoyevski as, for example, the novel The Karamazov Brothers can be related to this movement for certain aspects.

It is in the XIX century when the novel market separates into "high" and "low" production. The new superior production can be seen in terms of national traditions, as the novelistic genre replaced poetry as the privileged means of expression of the national conscience, that is, the creation of a corpus of national literatures was sought. Examples include The Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne (United States, 1850), Eugene Onegin by Aleksandr Pushkin (Russia, 1823-1831), I am a cat by Natsume Sôseki (Japan, 1905), Posthumous Memoirs of Blas Cubas by Machado de Assis (Brazil, 1881) or The Death of Alexandros Papadiamantis (Greece, 1903).

Lower production was rather organized into genres by a scheme that derives from the spectrum of genres of the 17th centuries and XVIII, though it saw the birth of two new popular novel genres: the crime novel with Wilkie Collins and Edgar Allan Poe and the science fiction novel with Jules Verne and H. G. Wells.

With the separation in production, the novel proved to be a medium for communication both intimately (novels can be read privately while plays are always a public event) and publicly (novels are published and thus become in something that affects the public, if not the nation, and its vital interests), a medium from a personal point of view that can encompass the world. New forms of interaction between authors and the public reflected these developments: authors gave public readings, received prestigious awards, gave interviews in the media, and acted as the conscience of their nation. This concept of the novelist as a public figure appeared throughout the 19th century.

20th century

The beginning of the XX century brought with it changes that would affect people's daily lives and also the novel. The birth of psychoanalysis, the logic of Wittgenstein and Russell, of relativism and the advances in linguistics cause the narrative technique to also try to adapt to a new era. The avant-garde in the plastic arts and the shock of the two world wars also have a great weight in the form of the novel of the XX century. On the other hand, the production of novels and the authors dedicated to them saw such growth in this century, and has manifested itself in such varied aspects that any attempt to classify it will be biased.

One of the first characteristics that can be appreciated in the modern novel is the influence of psychoanalysis. Towards the end of the XIX century, numerous novels sought to develop a psychological analysis of their characters. Some examples are the late novels of Maupassant, Romain Rolland, Paul Bourget, Colette or D.H. Lawrence. Intrigue, descriptions of places and, to a lesser extent, social study, faded into the background. Henry James introduced an additional aspect that would become central in the study of the history of the novel: the style becomes the best means to reflect the psychological universe of the characters. The desire to get closer to their inner life led to the development of the technique of the interior monologue, as exemplified by Lieutenant Güstel, by Arthur Schnitzler (1901), The Waves by Virginia Woolf (1931), and James Joyce's Ulysses (1922).

On the other hand, in the XX century, there was also a return to realism with the Viennese novel, with which The aim was to recover Balzac's realistic project of building a polyphonic novel that would reflect all aspects of an era. Thus, we find works such as The Man Without Qualities by Robert Musil (posthumously published in 1943) and The Sleepwalkers by Hermann Broch (1928-1931). These two novels integrate long passages of reflections and philosophical comments that clarify the allegorical dimension of the work. In the third part of The Sleepwalkers, Broch lengthens the horizon of the novel through the juxtaposition of different styles: narrative, reflection, autobiography, etc.

We can also find this realistic ambition in other Viennese novels of the time, such as the works of: (Arthur Schnitzler, Heimito von Doderer, Joseph Roth) and more frequently in other German-language authors such as Thomas Mann, who analyzes the great problems of our time, fundamentally war and the spiritual crisis in Europe with works such as The Magic Mountain, and also Alfred Döblin or Elías Canetti, or the Frenchman Roger Martin du Gard in Les Thibault (1922-1929) and the American John Dos Passos, in his trilogy U.S.A. (1930-1936).

The search and experimentation are two other factors of the novel in this century. Already at the beginning, and perhaps before, the experimental novel was born. At this time the novel was a well-known and respected genre, at least in its highest expressions (the "classics") and with the new century it shows a turn towards relativity and individuality: the plot often disappears, there is not necessarily a relationship between the spatial representation and the environment, the chronological journey is replaced by a dissolution of the course of time and a new relationship between time and plot is born.

With Marcel Proust's In Search of Lost Time and James Joyce's Ulysses, the conception of the novel as a universe finds its end. In a certain way it is also a continuation of the psychological analysis novel. These two novels also have the particularity of proposing an original vision of time: Proust's cyclical time of memory, Joyce's infinitely dilated time of a single day. In this sense, these novels mark a break with the traditional conception of time in the novel, which was inspired by history. In this sense we can also approximate the work of Joyce with that of the English author Virginia Woolf and the American William Faulkner.

The entry of modernism and humanism into Western philosophy, as well as the upheaval caused by two consecutive world wars, caused a radical change in the novel. The stories became more personal, more unreal, or more formal. The writer finds himself with a fundamental dilemma: writing, on the one hand, objectively, and on the other hand, transmitting a personal and subjective experience. This is why the novel of the early XX century is dominated by anguish and doubt. The existentialist novel of which Søren Kierkegaard is considered to be its immediate precursor with novels such as Diary of a Seducer is a clear example of this.

Another of the novel aspects of the literature of the beginning of the century is the short novel characterized by a gloomy and grotesque imagination, as is the case of the novels of Franz Kafka, also of an existentialist nature, such as The Trial or The metamorphosis.

Especially in the 1930s we can find various existentialist novels. These novels are narrated in the first person, as if it were a diary, and the themes that appear the most are anguish, loneliness, the search for a meaning for existence, and communication difficulties. These authors are generally heirs to Dostoevsky's style, and his most representative work is Jean-Paul Sartre's Nausea. Other notable existentialist authors include Albert Camus, whose minimalist style puts him in direct contrast to Sartre, Knut Hamsun, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Dino Buzzati, Cesare Pavese, and Boris Vian's absurdist novel. The Japanese novel after the war also shares similarities with existentialism, as can be seen in authors such as Yukio Mishima, Yasunari Kawabata, Kōbō Abe, or Kenzaburō Ōe.

The tragic dimension of the history of the XX century is widely reflected in the literature of the time. The narrations or testimonies of those who fought in both world wars, the exiles and those who escaped from a concentration camp tried to address that tragic experience and record it forever in the memory of humanity. All this had consequences in the form of the novel, since we see a large number of non-fiction stories appear that use the technique and format of the novel, such as If this is a man (Primo Levi, 1947), Night (Elie Wiesel, 1958) The human species (Robert Antelme, 1947) or Being without destiny (Imre Kertész, 1975). This type of novel would later influence other autobiographical novels by authors such as Georges Perec or Marguerite Duras.

Also in the XX century, dystopia or anti-utopia appeared. In these novels the political dimension is essential, and they describe a world left to the arbitrariness of a dictatorship. Notable works include Franz Kafka's The Trial, George Orwell's 1984, Aldous Huxley's Brave New World, and We by Yevgeni Zamyatin.

Latin American boom

The Latin American boom was a literary, editorial, cultural and social phenomenon that emerged between the 1960s and 1970s, when the works of a group of relatively young Latin American novelists were widely distributed in Europe and around the world. The boom is related in particular to Colombian Gabriel García Márquez, Argentine Julio Cortázar, Peruvian Mario Vargas Llosa and Mexican Carlos Fuentes. The key moment of boom is located in 1967, with the worldwide success of the novel Hundred years of solitude, by García Márquez, and the attribution of the Nobel Prize in Literature to Guatemalan Miguel Ángel Asturias. Two other authors later won the award: García Márquez in 1982 and Mario Vargas Llosa in 2010.

Although these four authors, according to Angel Rama and other scholars, represent commercially the boom In itself, previous authors — such as the Mexican Juan Rulfo, the Uruguayan Juan Carlos Onetti or the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges — had undertaken a renewal of literary writing in the first half of the twentieth century. On the other hand, the appeal was extended boom to any author of quality from the 1960s and 1970s once the impact of these four increased interest in Latin American literature throughout the world.

These iconic writers challenged the established conventions of Latin American literature. His work is experimental and, due to the political climate of Latin America in the 1960s, also very political. Critic Gerald Martin wrote: "It is not an exaggeration to say that the south of the continent was known by two things above all others in the 1960s; these were, first of all, the Cuban Revolution and its impact both in Latin America and in the third world in general; and secondly, the rise of Latin American literature, whose rise and fall coincided with the rise and fall of Cuba's liberal perceptions between 1959 and 1971".

The sudden success of the authors boom was largely due to the fact that his works are among the first novels in Latin America that were published in Europe, specifically by the Spanish publishers in Barcelona. In fact, according to Frederick M. Nunn, "the Latin American novelists became world-famous through their writings and their defense of political and social action, and because many of them were fortunate to reach markets and auditoriums beyond Latin America through translation and travel, and sometimes through exile and detachedness."

For his part, Chilean writer José Donoso holds in his Personal history of the boom (1972) a definition that excludes the great public and the favorable sanction of criticism to put the emphasis on a restricted but heterogeneous group of works published in the 1960s that give simultaneous idea of generation or movement and poetic art: "There had been a dozen novels that were at least remarkable, populating a space before the desert."Contenido relacionado

Stentor

Hans Magnus Enzensberger

Incunabula