Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens

Nosferatu, eine Symphonie des Grauens (Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror in Spain and Mexico, and Nosferatu in Argentina) is a 1922 German silent film directed by Friedrich Wilhelm Murnau. This is the first film related to Bram Stoker's novel Dracula. Initially not accepted by Bram Stoker's widow, who sued, it soon became a cult film.[citation needed]

Plot

The chronicler recounts how the plague reached the port city of Wisborg in 1838. Real estate agent Knock receives a request from Count Orlok of Transylvania to find him a house in Wisborg. Knock, apparently delighted with the earl's request, entrusts his young associate, Thomas Hutter, with the task of contacting him, traveling to the Carpathians to offer him the dilapidated house across from the Hutters' apartment. Thomas is full of energy and is glad to be able to set off on the journey. His young wife Ellen, however, reacts with concern and apprehension to his plans. Thomas leaves her in the care of a friend of hers, the shipowner Harding, and sets off. On the way he stops at an inn. The locals are apparently very afraid of Orlok and strongly urge the young man not to continue his journey.

Thomas had taken along for travel reading the 'Book of Vampires,' a compendium on bloodsuckers, which should have sensitized him to the subject; he ignores, however, all warnings and admonitions and continues on his journey. When his frightened guides finally drop him off on a bridge before the final ascent to the castle, Thomas has to continue the journey alone. A few kilometers from his destination, the count's sinister carriage picks him up in a dark forest and takes him to the gloomy castle of Orlok. Upon reaching the patio, he does not see anyone. Thomas wonders where all the servants are, but is then personally greeted by the lord of the castle. Count Orlok is no less sinister than his abode: a gaunt, bald figure with large eyebrows, a large hooked nose, and abnormally pointed ears. A dinner is prepared for Thomas. When he accidentally cuts his thumb with a knife, Orlok wants to greedily drink the blood, but then pulls away from him. Thomas will have to spend the night at the castle. After a heavy night's sleep, Thomas wakes up with two bite marks on his neck. However, he naively interprets them as mosquito bites and writes his wife a letter narrating what happened. When Orlok happens to see Ellen's portrait in a locket the next night, he immediately accepts Thomas' offer and signs the purchase contract without looking at him. Thomas begins to suspect that he will bring a fateful fate to his hometown. Orlok approaches the sleeping Thomas that night to suck his blood, but Ellen in Wisborg wakes up screaming and holds out her hands in supplication. The count turns away from his victim.

Ellen falls into a trance-like state and acts like a sleepwalker. Meanwhile, Thomas spends the day exploring Orlok Castle and finds the Count sleeping soundly in a coffin. The next night, he witnesses the Count hastily load coffins filled with dirt onto a cart. As soon as Orlok lies down in the last empty coffin and covers himself, the creepy cart speeds away. Thomas flees the castle, passes out in exhaustion, and is rescued by the locals, who take him to a hospital, where he is restored to health. Meanwhile, Orlok has arranged for the coffins to be rafted to Varna and loaded onto a sailing ship. The ship Empusa leaves for Wisborg with Orlok on board, while a recovered Thomas hurries home overland. On board the Empusa, the crew members die one by one from a mysterious illness. When the sailors investigate the possible causes of the epidemic and open one of the coffins, a horde of rats flee. Finally, only the captain and his first officer remain alive. Orlok comes out of his coffin at night. The first mate jumps overboard and the captain straps himself in at the helm. Like a ghost ship, the Empusa enters the port of Wisborg, where the stevedores only find the captain dead.

Knock, now in the asylum because of his appetite for bugs, is elated that the "teacher" has finally arrived. Orlok, with a coffin and the rats in tow, abandons the ship and wanders the city at night, spreading the plague. Harding finds the logbook of the Empusa, which tells of the deadly disease. The city declares a state of emergency, but it's too late: the plague is spreading through Wisborg, claiming countless victims. Not even Professor Bulwer, a follower of Paracelsus and an expert in epidemic diseases, can find an antidote to the plague. Knock has escaped from the asylum and is hunted by a mob who blame him for the plague, but he manages to flee and hide outside the city.

Thomas arrives in Wisborg. He brings with him the 'Book of the Vampire', in which Ellen reads that only a woman with a pure heart can stop the 'vampire'. voluntarily giving him her blood to drink, thus making him "forget the rooster's crow". Meanwhile, Orlok has moved into the desolate house across from the Hutters. He looks wistfully out the window into Ellen's room. The young woman pretends to be collapsing and sends Thomas to find a doctor. She can now sacrifice herself to the vampire unmolested, just as she had read in the book. Orlok, unknowingly believing that his wishes will come true, sneaks into her room and approaches Ellen to drink her blood. While he is satisfied with her, he suddenly hears the first crow of the rooster, he has forgotten the passage of time. It is already dawn and with the first ray of sun, the vampire turns into smoke. Thomas arrives at Ellen's room with the doctor and embraces her, but it is too late: Ellen is dead, but as she expected, with the end of the vampire the plague also ceases.

Cast

- Max Schreck - Count Orlok.

- Gustav von Wangenheim - Thomas Hutter.

- Greta Schröder - Ellen Hutter.

- Alexander Granach - Knock.

- Georg H. Schnell - Shipowner Harding.

- Ruth Landshoff - Annie.

- John Gottowt - Professor Bulwer.

- Gustav Botz - Professor Sievers.

- Max Nemetz - the Empusa captain.

- Wolfgang Heinz - the first Empusa officer.

- Heinrich Witte - the asylum guard.

- Guido Herzfeld - the taser.

- Karl Etlinger - the student with Bulwer.

- Hardy von Francois - the hospital doctor.

- Fanny Schreck - the hospital nurse.

History

The studio behind Nosferatu, Prana Film (named after the Buddhist concept of prana), was a short-lived silent-era German film studio founded in 1921 by Enrico Dieckmann and artist and occultist Albin Grau. His intention was to produce occult and supernatural themed films. Nosferatu was Prana Film's only production, as it filed for bankruptcy in order to dodge copyright infringement lawsuits by Florence Balcombe, Bram Stoker's widow.

Grau had the idea of making a vampire movie; the inspiration came from a war experience of Grau's: in the winter of 1916, a Serbian farmer told him that his father was a vampire and one of the undead.

Diekmann and Grau gave Henrik Galeen, a disciple of Hanns Heinz Ewers, the task of writing a screenplay inspired by Bram Stoker's novel Dracula, despite not having obtained the rights or the permission to produce a film about her. Galeen was an experienced specialist in dark romanticism who had already worked on Der Student von Prag (The Student from Prague) in 1913, and the screenplay for Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam in 1920. Galeen set the story in a fictional northern German port city called Wisborg and changed the names of the characters. The title Dracula was changed to 'Nosferatu, and the names of the characters were also changed: Count Dracula is here Count Orlok, for example. The role of him was played by Max Schreck (in German, schreck means 'scare'). Harker is Hutter, Mina is Ellen and Victorian England is the city of Viborg – or Bremen in the French version, as well as in the English one. He likewise added the idea of the vampire bringing the Wisborg plague via rats on the ship.

Filming began in July 1921, with exterior shots in Wismar. A shot of the St. Mary's church tower above the Wismar market with the water supply fountain served as the long shot for the Wisborg scene. Other places were the Wassertor (Water Gate), the south side of the church of St. Nicholas, the courtyard of the church of the Holy Spirit and the port. In Lübeck, the abandoned salt warehouse served as the Nosferatu's new home in Wisborg. Other exterior shots followed in Lauenburg, Rostock and on Sylt. The exteriors for the film which takes place in Transylvania were actually filmed in locations in northern Slovakia, including the High Tatras, the Vrátna valley, Orava castle, the river Váh, and the castle Starý hrad. The team shot interior shots at the JOFA studio and more exterior shots in the Tegel Forest.

For reasons of cost, cameraman Fritz Arno Wagner only had one camera available, and therefore only one original negative. The director followed Galeen's script carefully, following handwritten instructions on positioning the film. camera, lighting, and other related matters. Murnau prepared carefully; there were sketches that were to correspond exactly to each scene filmed, and he used a metronome to control the pace of the performance.

Florence Balcombe was unaware of the existence of Nosferatu until she received an anonymous letter from Berlin. The document included the program of a 1922 film event, with full orchestral accompaniment, which had had place in the marble garden of the Berlin Zoological Garden. The German film was described in the brochure as "a loose adaptation of Bram Stoker's Dracula." However, Bram Stoker's widow sued the film for copyright infringement and won the lawsuit.

The court ordered all Nosferatu tapes to be destroyed, but a small number of copies of the film had already been distributed around the world, and remained hidden by private individuals until the death of the film. Bram Stoker's widow. Over the years, more copies of these tapes were made (some of very low quality and with major cuts).

Nosferatu earned a reputation as one of the best films about the vampire myth and one of the greatest exponents of German Expressionism. Shot in natural settings, an unusual practice that distances it from the postulates of German expressionist cinema, many shots of Nosferatu are inspired by romantic paintings.

In the United States, Murnau's Nosferatu is in the public domain, and there are a large number of copies on video, generally of very low quality as they come from copies made from other copies one of the first tapes distributed for international screening. Many of them present notable differences in footage, since a different version of the film was shown in each country. Thus, the French copy is not the same as the German one, to give an example. However, restored editions of the film have recently been released in which almost all of the complete footage of the original film has been recovered. The most faithful reconstruction of the film was presented at the 1984 Berlin Festival.

Visual style

Location and composition of images.

Unusual for a German film of that time was the large number of outdoor scenes and the heavy use of real locations. The director thus rejects the artistic worlds of expressionist cinema, which were in vogue. such as those found in films such as The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (Robert Wiene, 1920) and Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam (Paul Wegener and Carl Boese, 1920). By contrast, Murnau's scenes are naturalistic and contain, according to Eisner, "some of the quasi-documentary quality of some of Dovzhenko's films". The film achieves its chilling effect through the intrusion of the sinister in everyday life, through the inversion of the meaning of idyllic scenes filmed in a naturalistic way. Gehler and Kasten comment: “Horror arises from the familiar, not from the abnormal.” Murnau manages to create a world, despite his passive, merely documenting attitude toward what is represented; through scenic composition, camera and framing. Lotte Eisner refers to the scene in which the black-robed pallbearers make their way down a narrow alley in a long procession when she states: 'The 'most expressive expression', as demanded by the Expressionists, it has been achieved here without artificial means".

Murnau creates this particular expressiveness in the interplay of film character and architecture: the vampire often stands in front of crooked doorways, under arches, or in front of coffin-shaped openings. His crooked nose and his hump are associated with architectural vaults and arches. Frieda Grafe sees a "parallelism of body and structure" which she continues in the metaphorical: both Orlok's Carpathian castle and his new home in Wisborg are desolate and dilapidated, corresponding to their loneliness and his position between life and death.

Lighting and camera

Nosferatu's lighting is characterized by its understated style, especially in the spooky scenes. Only individual figures or areas of the image are illuminated, while the rest of the scene remains in twilight or darkness. This creates three-dimensional shadow effects, in particular the shadow of the vampire's body, which runs ahead of him "like a bad omen" and thus expands the stage space off-screen. In Silke Beckmann's opinion, Murnau, who was educated in art history, based her lighting design on models for paintings, namely Rembrandt, Vermeer, Hendrick ter Brugghen, and Frans Hals. Murnau adhered to the conventions of the time in as far as shadow coloration codes are concerned: night scenes were colored blue, interiors were sepia-brown during the day, and yellow-orange at night. Murnau chose a pink color for the sunrise scenes.

Since the camera in Nosferatu generally remains static and motionless, Murnau works with movement and wobble within the rigid frame to energize events. As Orlok's ship slowly travels across the image from right to left, Murnau uses, according to Eisner, "the powerful impression of transverse motion" to create tension. Subjectivizations from the camera position serve the same purpose, for example when the vampire on the ship is filmed from a frog's perspective or when looking through the windows and parts of the frame and the glass bars protrude into the image.. The highlights of the subjectivized gaze are the scenes in which the figure of the vampire -looking directly at the camera- turns towards the viewer and thus breaks the fourth wall: "The vampire seems to break through the dimensions of the screen due to to its gigantic size. and directly threatens the viewer.” Other elements in Murnau's camera language are attempts to work with depth of field; for example, the sleeping Hutter is associated with the vampire who appears behind him in the doorway in a sort of inside montage.

Visual effects

Murnau employs cinematic trickery to mark Hutter's transition into the Count's world. The camera's shifting from frame to frame creates a choppy time period effect during Hutter's carriage ride. The director uses negative images in another scene and thus inverts the tonal values, creating the impression that the carriage is being driven through a ghostly white forest. In some scenes with the vampire, double exposure creates crossfade effects that can make him unreal and disembodied, passing through locked doors. Thomas Koebner denies these effects any disturbing effect and calls them "jolly pictorial jokes from the magic lantern era". Siegfried Kracauer is also of the opinion that the transparency of the tricks would prevent them from having a lasting effect on the viewer.: "It goes without saying that cinematic sensations of this kind run out of steam quickly."

Dramatics

Narrative style

On the surface, Nosferatu is a simple, folktale-like narrative that moves linearly toward an ending of inevitable consequences. A similar narrative structure can be found in Murnau's The Last (1924) and Faust (1926). On closer inspection, however, one perceives the different instances that illuminate the story from a wide variety of perspectives: the chronicler of the plague, the Hutter chief, the superstitious villagers, the 'Book of Vampires', as well as other writings such as the navigation log, texts from newspapers, letters and newspaper clippings. The viewer remains at obscure about the veracity and reliability of individual sources, especially since the narratives are often vague and ill-defined. Frieda Grafe, for example, notes that the chronicler's report is "too personal for a chronicle, too fictitious for a diary." For Michael Töteberg, Nosferatu is therefore "an attempt to explore the possibilities of cinema”, an experimental field for truth content in representation and an exploration of the position of cinema as a narrative authority.

Subtitles have an important narrative function. Their number is unusually high: 115. The texts, calligraphed by Albin Grau, show the chronicler's report in stylized Latin cursive on a paper background; the dialogues in a more modern script with bright colours, and the lyrics in German Kurrent script. The pages of the "Book of Vampires" They appear in Gothic script. Subtitles look like movie scenes: they're framed by fade-ins/fade-outs, the camera zooms in or out of them, and pages are turned.

Assembly

With more than 540 shots, Nosferatu is a film that was edited very quickly for the time. The influence of David Wark Griffith's revolutionary editing work in Intolerance (1916) is evident. However, according to Thomas Elsaesser, the viewer's perception of time is slowed by the fact that individual scenes are monolithic units in their own right and Murnau does not insert harmonious connections that accelerate the flow of the action, that is, he does not cut according to the continuity editing criteria. The director does not assign a clear chronological order to the events and does not link them according to causal criteria. The impression created for the viewer is that of a "dream logic" in which the cause-effect mechanisms are annulled and the comprehensibility of the events passes into the background compared to a more psychological description of the events. mutual dependencies and attractions of the characters. Seeßlen and Jung therefore describe the film as "a great mood picture much more than a 'narrative' film".

This dream cinema that is never fully developed leads to obvious logical breaks. Therefore, it is not clear why the earl is interested in the ruined house in Wisborg before his love for Ellen has arisen, or why Ellen is waiting for Hutter on the beach when in reality she should be waiting for him back for the first time. earth. These and other "mistakes" in time and space culminate in a montage in which the vampire and Ellen relate to each other, even though they are hundreds of miles apart: the count, still in his Carpathian castle, looks to the right, followed by a shot in which Ellen, being in Wisborg, extends her hands to the left in supplication. The line of sight of the two figures is connected, thus overcoming spatial distance. The scene evokes "not the impression of a spatial relationship, but a hunch or a visionary gift of the characters," notes Khouloki.

Elsaesser calls these ruptures in space and time the "logic of imaginary space," suitable for indicating the dependencies and manipulations of the protagonists: Orlok manipulates Knock, Knock manipulates Hutter, Ellen manipulates to Orlok in order to manipulate Hutter. The mutual "currents of attraction and repulsion" reveal a "secret relationship" between the characters: they are all "active and passive at the same time, initiator and victim, summoner and suspicious".

Music

Hans Erdmann titled his music for Nosferatu "Romantic-Fantastic Suite". According to composer and musicologist Berndt Heller, the film's subtitle “Symphonie des Grauens” reveals a “common misunderstanding”. Contrary to what is usually assumed, Erdmann would have relied less on elements generally associated with vampire material, such as horror, creepiness, and shock, than on imagery of moods that correspond to the director's intent to reflect on the film. film the transfiguration of nature and the reminiscence of folk tales. Like Murnau, Erdmann would illustrate in his music & # 34; the entanglement of demons in the legendary, the fairy tale and nature & # 34;.

Erdmann's score was published by Bote & Bock in editions for orchestra and for chamber orchestra. The ten pieces have typical “Kinotheken” titles of the time and are designed to be reusable: idyllic, lyrical, eerie, stormy, destroyed, fine, strange, grotesque, unleashed, and disturbed. Since the total playing time of the work is only about 40 minutes, Berndt Heller suspects that certain parts were repeated during the performances, for example, to repeatedly accompany the figures with leitmotifs. He also considers possible the repeated use of movements for new scenic situations, modifying the character of the piece, changing the interpretation indications in time and dynamics.

Since Hans Erdmann's score was considered lost in its original state, it was reconstructed by Berndt Heller and performed by a chamber orchestra for the first time on February 20, 1984 at the Berlin Festival, on the occasion of the presentation of the restored copy. under the supervision of Enno Patalas. The original version for symphony orchestra was performed in February 1987 at the Gasteig in Munich by the Munich Symphony Orchestra under the direction of Heller, as an accompaniment to a new colored version.

A reconstructed version of Erdmann's original score by musicologists and composers Gillian Anderson and James Kessler was released in 1995 by BMG Classics, with several missing sequences recomposed, in an attempt to reproduce Erdmann's style.

James Bernard, composer of the scores for several Hammer horror films in the 1950s and 1960s, wrote a score for a reissue, which was released in 1997 by Silva Screen Records.

In 2003, the Spaniard José María Sánchez-Verdú wrote a new soundtrack for the work, which comments on the film in a modern and coherent way and has been played live in Spain and Germany with great success.

In 2015, the film was screened at the Theater at Ace Hotel in Los Angeles with music by Matthew Aucoin and with the participation of the Los Angeles Opera Orchestra and direction by the composer.

In 2018, Hans Brandner and Marcelo Falcão rebuilt the "Fantastic-Romantic Suite" complete by Hans Erdmann and at the same time published film scores on this basis for piano, orchestra and chamber orchestra. In 2018 they performed the music for the first time in Brazil and since 2018 Nosferatu has been shown regularly with its musical version at the Babylon cinema in Berlin.

A rare version of the film includes musical accompaniment based on motifs by Johann Sebastian Bach, performed by 17 musicians from the Basel Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Armin Brunner.

The film was the basis for improvised concerts several times, for example in 2013 with Mathias Rehfeldt at an organ concert in Edmonton, or 2014 with Gabriela Montero at the piano in Berlin.

Themes

Nature

In addition to the filmed landscapes, the director presents a panopticon of the animal and plant world: nature scenes range from the microscopic detail of a polyp to a Venus flytrap, a striped hyena waiting for a werewolf, and frightened horses. Murnau thus symbolizes a "fatal chain of devouring and being devoured relationships," notes Elsaesser. Seeßlen and Jung comment: "Nature in all its devouring and sucking aspects demands its rights". According to Frieda Grafe, the scenes, which mostly originate from cultural films, have the function of "naturalizing the vampire", framing it as part of nature, to make its effectiveness seem even more strange, since which is natural and therefore irrefutable. As "undead" he is "beyond the categories of guilt and remorse", as Hans Günther Pflaum points out. In addition to his human-rational and animal-animal characteristics, the vampire himself is characterized by rigidity and jerky movements with a mechanical component. The figure thus eludes all attempts at classification; an aspect that contributes to the insecurity of the viewer: "All our certainties, which are based on clear limits, order, classifications, become unstable". On the other hand, the strong connection between the vampire and nature it is a reason for the viewer to empathize with the character: "When the terrifying figure is identified as part of nature, it is no longer possible to escape a feeling of pity". This is particularly evident in the scene of Orlock's death; the rooster's crow evokes omens of betrayal, the repulsive being is humanized in its agony. Seeßlen and Jung see pantheistic aspects in the integral appropriation of all manifestations of nature: there is a divine connection between all things that strives for harmony and perfection, but they also harbor a latent demonic danger. The instinct of animals (the skittish horses in the film) is the first to perceive this threat. In this context, Gehler and Kasten also refer to Murnau's painter friend Franz Marc and his metaphysical depictions of animals, in particular to the painting Fates of Animals from 1913, which represents the creatures that fight for the original harmony of paradise.

Romanticism

With his story set in the early 19th century and his emphasis on nature, Murnau follows a trend of the 1920s to seek a transfiguring and romantic vision of pre-industrial times. As with Fritz Lang, for example, in films like The Tired Death (1921), there is an escapist tendency towards the subject of the “old German”, Biedermeier, which can be interpreted as a fear of modernity. and to the convulsions of the post-war society. On the other hand, these directors used the most modern production techniques and organizational forms of the time to look back. Klaus Kreimeier, therefore, does not consider Murnau a reactionary artist: "The technicality, the geometric consciousness of his cinematographic work identify him [...] as a dedicated modernist".

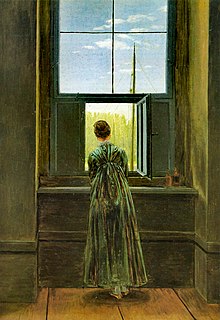

However, in his depictions of nature and pictorial compositions, Murnau clearly draws on nostalgic and transfiguring elements of Romanticism, most obviously on the pictorial motifs of Caspar David Friedrich, whose objectifications of transcendental states seem to have been the inspiration for many of the scenic structures of Murnau. Especially in the scenes with Ellen, Grafe recognizes a number of references to works by Friedrich, such as a woman at the window or the paintings on the beach. In these artificially designed cinematographic images, Ellen is "the incarnate melancholy that Freud described as bleeding from the inner life', notes Grafe. Other settings of the romance, such as the feeling of nature and the power of fate, are introduced early in the film: Ellen questions her husband, who brings her a bouquet of flowers: "Why are you killing the beautiful flowers?"; a passerby casually warns Hutter: "No one escapes their fate."

Politics and society

In his book From Caligari to Hitler (1947), Siegfried Kracauer relates the cinema of the Weimar era to the rise of dictatorship in Germany and calls the figure of the vampire " Like Attila [...] a 'scourge of God', [...] a figure of an exploitative and bloodthirsty tyrant". The people have a "love-hate relationship" 3. 4; with this tyrant: on the one hand, they abhor the arbitrariness of the despot; on the other hand, they are driven, through unfathomable power, by an anti-Enlightenment longing for salvation and exaltation. Christiane Mückenberger, calls the film "one of the classic tyrant stories", as well as Fred Gehler and Ullrich Kasten, who also classify Nosferatu as a "tyrant movie", follow Kracauer's point of view. Seeßlen and Jung also see the vampire as "the metaphysical symbol of political dictatorship". Like many similar characters in silent movies of the time, he is only tyrannical because he doesn't feel loved; he can only be conquered by love.

Albin Grau confirms that Nosferatu was intended to directly reflect the events of World War I and the turmoil of the postwar period. The film references the experience of war and is "a tool to understand, though often only unconsciously, what is behind this tremendous event that raged like a cosmic vampire". Gehler and Kasten also refer to the social and political instability of the time and see in the figure of the vampire a manifestation of collective fears. The shadow of the Nosferatu looms over an unstable and endangered society, tormented by dark fears. He arrives in a universe that has become vulnerable to violence and terror."

Koebner surmises that the plague epidemic may be a representation of the 1918 flu pandemic that had just emerged, noting that in Nosferatu the character Van Helsing, Dracula's vampire slayer, has no equivalent. Instead of actively resisting depravity, the characters remained passive and rigid; they thus join the tradition of Weimar cinema and have "participation in the contemporary pandemonium of restricted existences that do not seem to wake up from their nightmares".

Anton Kaes sees “anti-Semitic structures and motifs” in the depiction of terrifying foreignness in the figure of Orlok: Like the migrating “Eastern Jews” at the turn of the century XIX, the count hails from Eastern Europe. The characterization as "bloodsuckers" and images of rats spreading plague arouse in Kaes associations with anti-Semitic stereotypes, such as those later used in Fritz Hippler's propaganda film The Eternal Jew (1940). However, Thomas Koebner considers that this opinion is not correct; it would be too simple to transfer the instrumentalization of these motifs from the National Socialist era to Murnau's film.

Sexuality

The interdependence and manipulation of the characters in the film's editing can also be transferred to the realm of sexuality. Gunter E. Grimm describes Nosferatu as "the traumatic compensation for forbidden sexuality in bourgeois society". When Ellen finally allows the vampire into her bedroom, it can be read as a representation of ancient popular belief. that an innocent virgin could save a people from the plague. On the other hand, it is also evident that the young woman rebels with her act against the compulsory institution of marriage and tries to overcome the sexual frustration of her relationship with Hutter. Contrary to the asexually portrayed Hutter, the vampire is "the repressed sexuality that invades the idyllic life of newlyweds," as Kaes notes.

For Koebner, Nosferatu is thus a "weird love triangle, only half-encoded" and the earl-animal "the puritanical code of sexual appetite". to be free after his wife has joined the monster in a fatal way. Elsaesser biographically assesses the sexual connotation of the film: in the character of Orlok, the homosexual Murnau deals with "the change and repression of one's own homosexual desire by powerful doubles (Doppelgänger) who reflect the dark side of one's own sexuality". Stan Brakhage also assumes a biographical background. The constellation of figures refers to the "more personal own childhood terror" from Murnau; Hutter is reduced to the shy child who is at the mercy of the "father" Nosferatu. Elena is the mother figure who saves the child through his being and his actions.

Occult Symbolism

The film's realistic staging gives the impression that supernatural processes are anchored in the real world as something natural. In the depiction of the vampire as a magical, but nonetheless real figure, endowed with secret knowledge in an elitist-academic way, the influence of Grau in the film, who moved in occult circles, becomes evident. This influence is particularly visible in the design of the card that Knock receives from the Nosferatu at the beginning of the film. In two brief scenes, which together last only a few seconds, a cabalistic-looking encrypted text is seen, the code of which Sylvain Exertier considers to be unbreakable. In addition to signs such as the Maltese Cross and a swastika, letters of the Hebrew alphabet and astrological symbols can be seen. Sylvain Exertier interprets the text as an announcement of Orlok's – also spiritual – journey in the field of tension between the masculine principle, represented by Jupiter, the feminine, symbolized by Venus, and death, represented by Saturn. There are also decorative drawings of a skull, a snake and a dragon that Exertier considers “more spectacular than authentic”. It remains unclear whether the letter is a matter of "coquetry on the part of the director or a wink from the occultists".

Tributes

In 1979, Werner Herzog directed an adaptation of Nosferatu, the Vampire, entitled Nosferatu, Vampire of the Night. Shot on a shoestring budget, as was customary in Germany during the 1970s, Herzog's Nosferatu was a revision of the legendary original film, with plot changes. It became a critical and popular success. It did well at the box office. From its premiere to the present, it is considered a heartfelt tribute to Murnau's work and an excellent film in its own right. Klaus Kinski took the title role, accompanied by Isabelle Adjani and Bruno Ganz.

In the year 2000 the horror film The Shadow of the Vampire was released, directed by E. Elias Merhige. The film, which has features of black humor, tells a fictional story about the filming of the silent version of Nosferatu. Starring John Malkovich and Willem Dafoe, it is a fantastic horror story in the that a director (Murnau, played by Malkovich) creates a completely realistic vampire movie by hiring a real vampire (played by Dafoe) to play the role of Nosferatu.

José Fors adapted a rock opera titled "Orlok the Vampire".

In popular culture

Count Orlok has appeared in comics, such as Viper Comics' 2010 graphic novel Nosferatu, which tells the story of Orlok in a modern setting.

He also appeared in an episode of SpongeBob SquarePants titled 'Afterlife'. At the end of the episode it is revealed that he is responsible for the flickering lights in Squidward's horror story Tentacles. When they find out, he smiles, and the episode ends.

The characteristic design of Nosferatu is used as one of the Vampire clans from the White Wolf RPGs, Vampire: The Masquerade and Vampire: The Requiem.

Likewise, one of the characters in the game League of Legends, Vladimir, has an alternate appearance based on Nosferatu, this being called "Vladimir Nosferatu".

In the video game "Castlevania Symphony of the night" (whose name is also a reference to the original title "Symphony of terror") the final boss of the area called "Olrox quarters" His name is Olrox and he has the same appearance as Count Olrok, this being a very notorious reference.

Discography

The original score for Nosferatu was performed by Hans Erdmann.

- Nosferatu - A symphony of horror (BMG 09026-68143-2). Hans Erdmann's music for the film Nosferatu by F. W. Murnau in a complete version restored in 1994.

Later, other works inspired by this film were made:

- 1969: Peter Schirmann

- 1989: Richard Marriott

- 1989: Hans Posegga

- 1991: Timothy Howard

- 1997: James Bernard

- Nosferatu - Original soundtrack recording (Silva Screen FILMCD 192). The music of James Bernard, specialist in horror films. It was recorded in 1997.

- 2001: Carlos U. Garza and Richard O’Meara

- 2003: José María Sánchez-Verdú

- 2004: The Iker Jiménez Orgasmic Experience

- 2004: Bernd Wilden

- 2004: Nosferatu: symphony to dementia (Cister Order/In Black Productions). The music of the Mexican assembly Exsecror Vecordia, a tribute to Friedrich Murnau. Published in 2004.

- 2006: Bernardo Uzeda.

- 2008: Live music in the film cycle: "Cine Mudo + Improvised Music" organized by the Goethe Institut de Santiago de Chile. The musicalization was in charge of guitarist and improvisator Ramiro Molina.

- 2015: The Mafia of Love

- 2015: "Musicalized Live at Teatro Condell, Valparaíso, Chile, in two free interpretation sessions organized by REPLICA MAG Y CINE INSOMNIA, the first by Carlos Reinoso with electronic sounds and later by Sergio Miranda with experimental guitar.

Contenido relacionado

Under Suspicion (1943 film)

Tristana (film)

Ingrid Bergmann