North American languages

The languages of North America are reflected not only in the indigenous peoples of the continent, but also in the European colonies. The most widely spoken languages in North America are English, Spanish, and French.

History

Most historians agree that the Native American population came from Asia and came to the Americas through the Bering Strait, which can be seen in the racial traits that Native Americans share with the peoples of Asia, such as the Amerindian features that appear on the backs and buttocks of newborns and that disappear with growth.

The date set for the first waves of migration to the American continent from Asia is twenty thousand years BC. C., being reasonable to think that there were later others. For example, many researchers believe that the Eskimo-Aleut migration from Asia took place around 3000 BCE. C., although it can be assumed that since there were still Eskimo settlements in Asia, in the extreme northeast of Siberia, Eskimo emigration could have been in the opposite direction, that is, from Alaska to Asia.

The first known contact between Europeans and natives of the New World took place shortly after the year 1000 when Leif Erikson set foot on 'Vinland,' possibly the Labrador Peninsula or anywhere between and there. Maine, and found the skrälingar, whom he defines as 'little fellows'. It is not clear if with that expression he refers to the Eskimos or the Indians; soon after Leif's brother Thorwald was killed by a skrälingar arrow. Four centuries later, Jacques Cartier was negotiating with Iroquois-speaking people in Quebec. By 1620 settlers from England were in contact with the Indians, who appear to be Iroquois, in New England.

As a result of the Anglo-French flow, Indian words, especially Iroquois, were recorded by explorers and missionaries, even advancing the identification of the genetic relationship between the different forms of the Iroquois family. However, the study of the Indian languages of North America was fragmentary and has no comparison with the more in-depth study carried out in Mesoamerica. It was not until the work of Franz Boas (1858-1942) that fertile anthropological, linguistic and ethnological work was carried out in the scientific study of the Indian languages of North America.

When Europeans colonized North America there were some 300 native languages, followed by a history of erosion, decline, and in many cases extinction. Today there are some 50 or 100 languages left, most of which are spoken by older people, being known by a few dozen people or at most hundreds.

Numbers

Regarding the number of past and present speakers, no exact figure can be established, only an estimate and by comparison. It is believed that when the Europeans arrived in the New World, in the north of Mexico about a million and a half people spoke their own languages, which today has been reduced to about two hundred thousand.

Five languages, Choctaw, Muskogui, Dakota, Cherokee, and Pima-Papago, have between 10,000 and 20,000 speakers, and two, Cree and Ojibwa, bring that number up to 40,000 to 50,000. The only language that breaks the general perspective of decline is Navajo, which has not only achieved stability but is growing in number, around 100,000 speakers.

Phylogenetic classification

The classification of Native American languages, in general, is not without controversy. By the middle of the 20th century North American Amerindian languages have been classified into sixty different families, with no genetic relationship demonstrated by linguists that brings them together

Major John Wesley Powell, founder of the Bureau of American Ethnology, divided languages into 58 stems in 1891 based on their lexical similarity. Subsequently, other classifications have been made based on more technical and detailed analyses, so that the definitive genetic relationships between many North American Indian languages have been established, having reconstructed their ancestral models: proto-Algonquin, proto-Atabascan, proto-Iroquois, etc. However, none of these reconstructions has shed light on the question of the origins of the American Indians.

In North America there are three groups of languages spoken today:

- Native or aboriginal.

- Imported from Europe (mainly Spanish, English and French) and predominantly numerically and socially.

- Contact languages, i.e. pidgins and criollos.

Aboriginal languages can be classified into about 40 well-established families, plus another thirty unclassified or isolated languages. Various authors have conjectured that some of these 40 families could be related to each other in an attempt to reduce the number of families. However, these higher groupings do not have as much consensus and many of the proposed macrofamilies are highly controversial. Edward Sapir proposed a grouping into 7 superfamilies:

- Esquimo-aleutiana

- Na-dené

- Hokana

- Penutia

- Azteco-tanoana

- Macro-algonquina

- Macro-siux

This classification in only seven groups is highly controversial and rejected by most specialists, yet it was retaken by the even more controversial classification of Joseph Greenberg (1987), which proposed the so-called amerindian hypothesis that reduces the total number of families in North America to only three. Of the families proposed by Sapir only 1 and 2 are universally accepted, families 3 and 4 have partial acceptance (i.e., they are accepted by reducing the number of languages within those categories regarding the lists proposed by Sapir). The last three are almost universally rejected although some authors have made similar hypotheses reducing the number of languages within those groups, which have more acceptance than Sapir's original proposal.

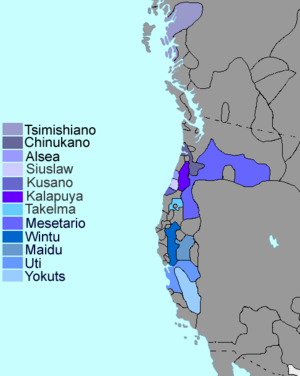

In addition, an almost extinct group of isolated languages could be added on the north-west coast of the Pacific and the Dutch language group in California, Arizona and Mexico.

Writing

In North America, due to the influence of European writing -or in many cases due to its direct study- many tribes developed some forms of writing. Like the syllabaries of the Cherokee (a system that represents each different syllable by a sign), the Micmac, the Cree and the Greenland Inuit.

Grammar

Consonants

Glottal consonants (they have it dwarf) appear in Athabascan, Sioux and Salish. The aspirates in the siux, pomo and yuma families. Retroreflexes (or cacuminales) in Pomo, Yuma, and other California languages. Velars appear in the Eskimo-Aleut, Northern Yuto-Aztec, and California Athabascan families among the languages of the North American subcontinent. The nasal velar consonant is the phoneme ng and is possessed by the Eskimo, Haida, Yuma, and California Athabascans. Voiceless nasals and semiconsonants are phonemes similar to m, n, y, and w, appearing in some dialects of Iroquois. The voiceless i is found in some Eskimo variants, in others from California, and in the Athabascan, Salish, and Muskogee subfamilies. The Lateral affricate consonants appear in the Athabascan, Sahaptin, Kwakiutl, and Nahuatl subfamilies.

Vowels

Deaf or sibilant vowels appear in the Zuni, Hopi, and Keres groups (all spoken by the Pueblo people), the Yuto-Aztec languages, and the Cheyene group, of the Algonquin-Ritwan family. Nasalized vowels (as in Portuguese and French) are possessed by the Athabascan, Eastern Algonquin, Sioux, Muskogee, and Kiowa-Tano groups. High and middle i occur in Comanche and coastal Tsimshian.

Accents

A difference in stress or intensity distinguishes one word from another. The Mohawk and Cherokee (Iroquois), Crow (Sioux), Cheyene, Arapajó and Penobscot, from the Algonquin group, have an accent of intensity.

Colloquial Forms

In the aboriginal languages of the United States and Canada, they use different colloquial forms depending on whether they are spoken by women or men, as in Yana, Muskogee, and Atsina. There are also ritual languages that have special forms of speech for ceremonies, such as Zuni, Iroquois, and others. In multilingual regions, exchange jargons arise. They are simplified languages and among them are Chinook, Mobilio and Delaware. A few other languages develop whistling forms of speech, where the melody of the whistles runs parallel to that of the tones of the language. It is used in courtesy situations and appears in kickapoo (Algonquian-Ritwa), which is a Mexican language close to Texas.

Syntactic Order

Syntactic order varies from language to language, both in its importance and in its function. In some, this syntactic order is relevant, like some Californians that follow subject-object-verb.

Languages that indicate whether the subject or object of a sentence is the same or different from that of a previous sentence have selective reference. In Spanish, for example, if someone says: & # 34; Pepe saw Maite when she was leaving her house & # 34;, the listener cannot know who was leaving or whose house it is, because there is no selective reference. This trait is possessed by the Algonquian, the Paiute, the Papago, and the Yuma.

Affixes

Instrumental affixes (prefixes, infixes and suffixes) are added to verbs to indicate with which instrument or by which procedure the action is performed. This distinction is shown, for example, by the Karok language, which in the prefix pa- indicates the use of the mouth. Thus pácup means 'kiss' and paxut means 'to hold the mouth'. A system of prefixes exists in Haida, Tlingit, and other North American languages.

Contenido relacionado

Marseilles

Language teaching

Berrocalejo (Caceres)