Nihilism

Nihilism (from the Latin nihil, "nothing") is a philosophical doctrine that believes that in the end everything is reduced to nothing, and therefore so nothing makes sense. It rejects all religious, moral and epistemological principles, often based on the belief that life has no meaning, that there is no deity, since nature and the universe are indifferent to human beings, their values and their suffering., that there is no ultimate teleological end in the presence of a divine order since God has died, that there is no absolute truth and that reality is apparent. Nihilism is often presented as existential nihilism, a form in which life is held to lack objective meaning, purpose, or intrinsic value. Nihilism can be considered a social, political, and cultural criticism of values., customs and beliefs of a society, to the extent that they participate in the meaning of life, denied by said philosophical current.

The term nihilist was created by the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev in his novel Fathers and Sons (1862): "Nihilist is the person who does not incline before any authority, which does not accept any principle as an article of faith" and it spread extraordinarily in the Russian society of the second half of the XIX century with different meaning: for conservatives it was offensive, for the democratic revolutionaries it was a sign of identity.

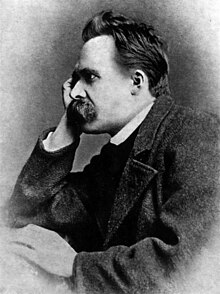

Friedrich Nietzsche structured the conceptualization of the term, but it already existed as a current in ancient Greece represented by the Cynic school and skepticism.

Nihilism denies that which claims a higher, objective or deterministic sense of existence since these elements do not have a verifiable explanation. On the other hand, it is favorable to the perspective of a constant or concentric evolution of objective history, without any higher or linear purpose. He is a supporter of vital and playful ideas, of getting rid of all preconceived ideas to make way for a life with open options for fulfillment, an existence that does not revolve around non-existent things.

In this sense, nihilism does not mean believing "in anything," nor pessimism, much less "terrorism" as is often thought, although these meanings have been given to the word over time. In any case, there are authors who call nihilism, understood as the negation of all dogma to open up infinite and undetermined options, call it positive nihilism, while the sense of denial of all ethical principles that negligence entails or self-destruction they call it negative nihilism, although they are also known as active nihilism and passive nihilism.

One of the most distant references is found in the sophist philosopher Gorgias who stated: "Nothing exists, if something exists it is not knowable by man; if it were knowable, it would not be communicable" or in the vital attitude of the disciple of Antisthenes, Diogenes of Sinope.

Philosophical concept

Nihilism has very ancient antecedents and is already found in some Hebrew philosophical texts, such as Ecclesiastes. Other philosophers who have written on this subject include Friedrich Nietzsche, Jean Paul Sartre, and Martin Heidegger. Nietzsche described Christianity as a nihilistic religion because he evaded the challenge of finding meaning in earthly life, instead creating a spiritual projection where mortality and suffering are suppressed rather than transcended. Nietzsche believed that nihilism was the result of the death of God, and insisted that it must be overcome, giving new meaning to a monistic reality. He sought a pragmatic idealism instead of Schopenhauer's cosmic idealism.

Heidegger described nihilism as the state in which nothing remains of Being itself, and argued that nihilism rests on the reductionism of Being to a mere value. Nihilism is the process that the consciousness of Western man follows and that would be expressed in these three moments:

- Nihilism as a result of the denial of all existing values: it is the result of doubt and disorientation.

- Nihilism as a self-affirmation of that initial denial: it is the moment of reflection of reason.

- Nihilism as a starting point for a new valuation: it is the moment of intuition, which is expressed in the will of power, in which the value of the will is expressed.

In this regard, Heidegger affirms the existence of two types of truth; that made by God in which everything corresponds to the idea with which it was created, and the truth understood by humans in which everything adapts to their understanding, denying the idea of absolute truth. More importantly, for Heidegger "There is only truth as long as Dasein exists"; thus, he considers that truth is intrinsically related to the existence of one's own being, and that when this is lost, the concepts of truth that it synthesizes are lost with it. So that nothing has its own essence or truth, but rather takes meaning in the way that Dasein conceives it, to lose it again once it ceases to exist.

.

This is the basis on which, according to Nietzsche, the new philosophy must be built. Man causes, first of all, the death of God or the destruction of expired values. Secondly, man becomes fully aware of the end of these values or the death of God and is reaffirmed in it. Thirdly, and as a consequence of all of the above, man discovers himself as responsible for the destruction of values or the death of God, discovering, at the same time, the will to power, and intuiting the will as maximum value; thus opens the way to new values.

For Sartre, being (man) comes to generate nihilation, since he is a denier. “Because denial is denial of existence. By it, a being (or a way of being) is put and then rejected into nothingness”

Popularization of the term

Although the term was popularized by the Russian novelist Ivan Turgenev in his novel Fathers and Sons (1862) to describe the views of the emerging radical Russian intellectuals, the word nihilism was introduced into philosophical discourse. first time by Friedrich Heinrich Jacobi (1743-1819) in a letter sent to Fichte in 1799.

Jacobi used the term to characterize rationalism, and in particular the critical philosophy of Immanuel Kant in order to carry out a reductio ad absurdum according to which all rationalism (philosophy as criticism) reduces to nihilism, and therefore must be avoided and replaced with a return to some kind of revelation or transcendent knowledge.

The intellectuals Turgenev described in his novel were mainly upper-class students who were disillusioned with the slow progress of reformism. In Fathers and Sons Turgenev wrote "nihilist is the person who does not bow before any authority, who does not accept any principle as an article of faith", in the sense of a person who is critical of everything. what surrounds you. The main spokesman for this new philosophy was Dmitri Pisarev (1840-1868).

The word soon became a term of derision for radical younger generations. It is often used to indicate a group or philosophy characterized by a lack of moral sensitivity, belief in truth, beauty, love, or any other value, and no respect for prior social conventions.

The Cynical School

The historical background of nihilism is in the Cynic school, founded in Greece by Antisthenes during the second half of the IV century. to. C. and whose greatest representative was Diogenes de Sinope. Like the Russian nihilists of the mid-19th century, the cynics criticized the order and morality of their time through satires against the corruption of customs and vices of the Greek society of his time, and practicing an often irreverent attitude: the so-called "anaideia".

Antisthenes was a disciple of Gorgias until he decided to found his own philosophical school. He did it in a gym on the outskirts of Athens called Cinosargo, which means "white dog". His followers began to call them kinics (& # 34; dogs & # 34;, in Greek) since their behavior was similar to that of dogs. Antisthenes lived by his own law, the one he himself chose for himself. Established laws, social conventions were not for this wise man who, like all cynics, despised norms, institutions, customs and everything that represents a bond for man.

Diogenes of Sinope was a disciple of Antisthenes. He chose to lead an austere life and adopted the cynical outfit, like his teacher. From his early days in Athens he displayed a passionate character. He radically puts into practice the theories of his teacher Antisthenes. He takes freedom of speech to the extreme, his dedication is to criticize and denounce everything that limits man, particularly institutions. He proposes a new valuation against the traditional valuation and constantly confronts social norms. He considers himself a cosmopolitan, that is, a citizen of the world, the cynic is found anywhere as in his house and he recognizes the same in others, therefore the world belongs to everyone. Legend has it that he got rid of everything that was not essential, he even abandoned his bowl when he saw a boy drink water in the hollow of his hands.

Crates of Thebes was a wealthy citizen with a good social position, who gave up his entire fortune to become a cynical philosopher. He was a disciple of Diogenes and a teacher of Zeno de Citio. Crates, unlike his teacher, was a kind and easy-going man, earning him the nickname "the philanthropist" as well as the "door opener." because people called him at his house to ask him for advice and chat with him. For Crates, philosophy frees him from his external slavery, in terms of family, property or social customs and also frees him from internal slavery, from his opinions, maintaining his radical individual freedom.

Russian nihilism

Development

The Russian cultural phenomenon known as nihilism developed during the reign of Alexander II (1855-1881), a liberal and reformist tsar. The 1960s is considered the decade of nihilism. The loss of the Crimean War (1854-1856), the opening of the regime to the outside (not only an economic opening, but also a cultural and ideological one) and the relative freedoms granted by the tsar –for example, in the press– served as a broth of culture for this new subculture. Fundamentally intellectual in nature, nihilism represented a reaction against the old religious, metaphysical and idealistic conceptions. The young nihilists, portrayed as rude and cynical, fought and ridiculed their parents' ideas. His sincerity bordered on offense and bad taste, and this attitude was what seemed to most define this movement. The contemptuous and negative attitude was perfectly portrayed in the character Bazarov from the novel Fathers and Sons by Ivan Turgenev.

In the extreme sentimentality of parents, these youngsters saw only one form of hypocrisy. They watched as their romantic parents exploited their serfs, mistreated their wives, and enforced strict discipline in their homes, and then, paradoxically, turned to making poems and exhibiting ridiculous behavior, as the noted anarchist Piotr Kropotkin later illustrated in his Memoirs of a Revolutionary (1899). "The nihilists rejected and abandoned, in the name of progress, everything that could not be scientifically justified, such as superstitions, prejudices and customs."

They criticized aestheticist positions in art for reveling in beauty in the abstract and lacking real social utility. They also adopted a utilitarian ethical stance called "rational egoism" for which they sought to redefine social relationships in areas such as friendship, love or work.

Russkoe Slovo: first stage (1859-1862)

The nihilistic tendency was a part of the Russian radicalism of the time. He had his means of expression in a publication called Rússkoe Slovo (Russian Word, Русское слово ), created in 1859. But it was not until the incorporation of the young Dmitri Písarev (1840-1868) the year 1860 that the publication became representative of this trend. Pisarev –despite having a literate background– dedicated himself to popularizing the latest advances in natural sciences, and especially in physiology. The greatest ideological referents were the German materialists, called vulgar for their reductionism and extreme determinism. He highlighted the triumvirate formed by Büchner, Moleschott and Vogt. Pisarev interpreted personal, affective or work relationships, and even historical development, from a physiological perspective. In one of his articles on Moleschott, he went so far as to state that the hostility towards progress was the consequence of a poorly nutritious diet and that, on the contrary, a balanced diet would lead to a full development of intellectual potential. Contrary to idealism, Pisarev described ideals as hallucinations, because they could not be experienced through the senses. Another of the foundations of the movement was positivism, with which these young people shared their eagerness to enlighten and their defense of the scientific way of thinking. Positivist authors such as Comte or Buckle were a clear reference for Pisarev and other young nihilists.

In his article "Bazarov" (February 1862) Pisarev identified with the character of Fathers and Sons , with whom he greatly sympathized, both for his extreme individualism and for his scientific demeanor. In this article, Pisarev argued that no type of knowledge or conviction should be accepted as an article of faith. Only the senses could constitute the basis for the construction of knowledge, leaving aside all speculation and empty theorizing. The scientific method, with observation and experimentation, perfectly nourished this need to assimilate knowledge physiologically. The sensualist conception was also used by Pisarev to justify the behavior of individuals. These should be guided by natural impulses and by a calculated selfishness, despising conventions and traditions of all kinds. Religious, family or social prejudices and obligations should also be rejected. Bazarov thus became the referent of the publication. "If Bazarovism is a disease, it is the disease of our time," Pisarev sentenced. Bazarovism or nihilism spread like cholera, and no one could stop it, he expressed.

A wave of repression against radical institutions and publications ended that same year with the arrest of Pisarev and the closure of Russkoe Slovo; the intellectual Chernyshevsky and “his” publication Sovremennik (The Contemporary) suffered the same fate. Pisarev protested anonymously against the repressive campaign and defended the intellectual Herzen from the slanders poured out by a tsarist agent named Shedo-Ferroti. He adopted an excessively violent tone this time, ending the pamphlet with an invitation – to the “alive and fresh” youth – to the complete annihilation of the “corrupt and rotten” royal house. However, the illegal printing was detected and the clues obtained led to the identity of Pisarev. The episode ended with his imprisonment in the St. Peter and St. Paul Fortress, where he would remain for four years (1862-1866).

Despite this chapter, a few months later Russkoe Slovo was allowed to reopen and Pisarev was granted permission to continue publishing from prison.

Russkoe Slovo: second stage (1863-1866)

The second stage of Russkoe Slovo was marked by the incorporation of the young Varfoloméi Záitsev (1842-1882) in 1862 and the definitive ideological break of this publication with the other radical publication of the time, Sovreménnik (The Contemporary). Varfoloméi Záitsev followed a similar orientation to that of Pisarev, sharing the same ideological bases as him. He stood out for the aggressive tone of his writings. The divergence began with the identification of Pisarev with Bazarov, who was seen by Maksim Antonovich –one of the editors of the Sovremennik– as cold and unemotional, and a rude caricature of Pisarev's youth. The time. But it was the confrontation between Mikhail Saltykov-Shchedrin and Zaitsev that finally determined the division. The young nihilists appeared in the eyes of the populist Saltykov as a bunch of charlatans loaded with pessimism and negativity. And for Zaitsev and Pisarev the populist positions, that is, the belief in the illiterate and ignorant peasant as the engine of all progress in Russia, were supremely stupid. They also clashed on some ideological references. In the Sovreménnik Hegelian philosophy prevailed (specifically the left-wing Hegelianism represented by Feuerbach and his humanist religion) and in the Rússkoe Slovo vulgar materialism and radical scientism. For Pisarev and Zaitsev, Hegel's philosophy and dialectic in general constituted an accumulation of meaningless abstractions.

The youth of Russkoe Slovo were characterized by their “rational egoism”, which was opposed to the altruism and personal sacrifice preached by the members of the Sovremennik and later by the populists of the seventies. In his writings on Darwin's work, The Origin of Species (the Russian translation came out in 1864), Pisarev saw this egoism scientifically justified, since each species acted solely according to of own interest. Zaitsev adopted a position linked to social Darwinism, maintaining the inferiority of the colored races –inspired, above all, by Karl Vogt– and denying that they had an important role in history. Another of the points of discussion between the two radical publications was the one referring to art. For Antonovich, for example, aesthetic pleasure was a natural necessity; Pisarev and Zaitsev criticized, in contrast, the aestheticist positions in art (the so-called "art for art's sake") for lacking social utility.

Pisarev developed a whole theory of rational egoism that, especially in articles like "Realists" (1864) or "Thinking Proletariat" (1865), became a variant of utilitarianism. On the one hand, the “liberation of the personality”, which in his first articles represented the purification of one's own ego of everything that is artificial or imposed by external agents, such as duties and obligations. And on the other, this new conception of rational egoism, which progressively acquired a utilitarian tone, abandoning the more hedonistic initial conceptions. Pisarev proclaimed in “Thinking Proletariat” that egoism, rationally conceived, did not have to be at odds with love for humanity, that individual interest could coincide with the common good. If the new men and women dedicated themselves to tasks of social utility – and Pisarev saw scientists as a new avant-garde – the contradictions were eliminated. In "Realistas" Pisarev dealt with issues such as women's liberation, the necessary industrialization in Russia, the need for popularizers of natural sciences and – in opposition to the populist tendency – the uselessness of undertaking the “go to the people” with such a large number of illiterate peasants.. It was not yet the time of a “mass enlightenment” and the only thing that could bring progress to Russia were scientists, technicians and other “thinking proletarians”.

The sensualist, positivist, Darwinist and extremely selfish attitudes of the Russkoe Slovo youth set them apart and confronted, thus, the members of the Sovreménnik, a publication in which altruism was preached and mythologized to the people, continuing the moralistic tradition of publicist Nikolai Dobroliúbov, who was also a member of that publication and who died prematurely in 1861.

Although Pisarev and Zaitsev shared many points in common with Chernyshevsky, they differed from him in their positions. Later Chernyshevski criticized the positivist and Darwinist positions of these young people, although he published his novel What to do? (1863) inspired by the new trend and its moral character. Chernyshevski is known to be a supporter of agrarian socialism based on the mir, or Russian rural commune. Pisarev, on the other hand, received great influence from Saint-Simon and adopted an industrialist position. Always from an apolitical dimension, he defended peaceful economic and social development through educational and modernizing work (industry, technology, etc.). Zaitsev lamented the low intellectual and educational level of the Russian peasantry and, unlike later populists, was skeptical of this social class, seeing in the Western worker a much more advanced social class. Zaitsev, like his publishing partner Nikolai Sokolov, economics writer for Russkoe Slovo , identified with the thinking of French anarchist Pierre Joseph Proudhon.

The closure of Russkoe Slovo and later influences

With the attack on Narodnaya Volya member Dmitri Karakozov (April 1866), the radical publications of the time, Russkoe Slovo and Sovremennik, were closed down by feed subversive tendencies. Despite this, Grigori Blagosvetlov, former editor of Russkoe Slovo, was allowed to publish in [[Delo (magazine s. XIX)|Delo]] (The fact), where other members of Russkoe Slovo participated, such as Piotr Tkachov or Nikolai Shelgunov who, unlike Pisarev and Zaitsev were not representative of the nihilistic tendency. Pisarev participated in this publication, but after some disputes with Blagosvetlov, he broke with it. He would die, supposedly drowned, in the year 1868. It is hypothesized with suicide (several attempts in the past by Pisarev make this hypothesis credible). Zaitsev, who was forbidden to publish, fled into exile in 1869, linking himself to Swiss anarchist groups. He would also join Swiss anarchist groups Sokolov, former economic editor of Rússkoe Slovo , who escaped in 1872 from his captivity.

The nihilist subculture thus lost its means of expression and its main representatives. Yet Pisarev's works continued to hold a significant fascination for Russian youth until the early XX century. Nihilism came to be described as a stage of early youth through which many passed. Pisarev's followers (or pisarevtsy) were criticized by Narodnaya Volya members of the 1970s. Nikolai Mikhailovsky, a well-known radical poet, saw in this current an egoism and a solipsism contrary to the populist spirit. The Narodnaya Volya terrorist Lev Tikhomirov criticized Pisarev's followers for basing everything on personal impulses, ignoring the people, and described nihilism as aristocratic pretension, born in the shadow of a decadent nobility. More than an adaptation of English utilitarianism to Russian reality, Tikhomirov considered that Russian nihilism was a caricature of it and that his alleged utilitarianism was only an excuse for immorality and an appeal to dissolute life.

In culture

In literature

The term "nihilism" It was popularized by Ivan Turgenev in his novel Fathers and Sons, in which the hero, Bazarov, is a nihilist who manages to convince others to adhere to this philosophy as followers. Only love makes him doubt his principles based on nihilism.

Anton Chekhov represented nihilism in his work The Three Sisters. The phrase “what does it matter?” and its variations were used by the characters on numerous occasions in response to events in the novel. The meaning of some of these events suggests that the characters used nihilism as a method of coping with their reality. In addition to the above, Chekhov is known for being the main representative of the literary genre known as "piece" that is characterized by being stories whose protagonists have a wish, acquire the opportunity to achieve it and for some reason are unable to make it come true, for what these stories end as they begin, giving the appearance that “nothing happened” during the story. Something that by itself can be interpreted as an addition of Chekhov's work to nihilism, since the life of his characters has no meaning as long as there are no apparent changes in their lives after the development of events.

Ayn Rand vehemently denounced nihilism as an abdication of reason and the pursuit of happiness, which she saw as the moral purpose of life. For this reason, most of the villains in her works are consummate nihilists. Examples of this are Ellsworth Mockton Toohey in The Spring who is self-defined as a nihilist and the corrupt government in Atlas Shrugged whose members are unconsciously motivated by nihilism, this is shown in the book's depiction of American society with the popular false phrase "Who is John Galt?" being used as a defiant way of saying "Who knows?" or "Who cares?" that characters who have given up in life utter constantly. The philosophical ideas of the French author, the Marquis de Sade, are commonly pointed out as principles of nihilism.

On TV

The animated series Rick and Morty presents several nihilistic ideas, such as the meeseeks (in the chapter "Meessek and Destroy"), beings who only want to end their life since for they are torture. Or as the protagonist Rick, who multiple times tries to metaphorically kill God and never presents a belief in anything.

Another animated series, Daria, shows a cynical and nihilistic teenager, with little motivation for the environment around her and people in general; Although she does not become suicidal, her lack of motivation and her sense of things speak for themselves. The series was deeply rooted in the nihilism of Generation X in the 90's.

At the movies

Three of the antagonists in the 1997 film The Big Lebowski are explicitly described as “nihilists”, however they cannot be seen exhibiting any nihilistic behavior or comments throughout the film. Regarding the nihilists, the character Walter Sobchak comments: "They will say what they want about the principles of National Socialism but at least it is a doctrine."

In the 1999 film The Matrix the protagonist Thomas A. Anderson stores stolen files in an empty copy of Jean Baudrillard's work Simulation and Simulation, specifically under the chapter "On Nihilism". Likewise, the main antagonist, Agent Smith, is also frequently portrayed as a nihilist, which is most evident in [[The Matrix: Revolutions]] when he complains about peace, love and security. justice, describing them as insignificant.

The film Fight Club also exploits the characteristic concepts of nihilism by exploring the contrasts between the artificial values imposed by consumerism and the pursuit of spiritual happiness.

In turn, Heath Ledger's portrayal of the Joker shows a mixture of anarchist ideas and principles of nihilism by describing himself as "an agent of chaos" and burning a mountain of money while stating that crime "is not about the money. It is about sending a message: everything burns”. In this regard, Alfred Pennyworth declares: "There are men who do not look for anything logical, like money - they cannot be bought, intimidated or convinced - there are men who just want to watch the world burn."

Video Games

The video game Nier: Automata contains allusions to Nietzsche and nihilism as a whole. One of the game's endings, known as "Final E", has been interpreted numerous times as the reject of existential nihilism, causing the player to repudiate the notion of a meaningless world in order to save the protagonists of the game. game.

In Revelations: Persona the final boss is the representation of the nihilistic thoughts of one of the main characters.

Music

The song Nihilist Blues by the British band Bring Me the Horizon, makes direct reference to nihilism in its lyrics.

The song 'Nihilism' from the band Siniestro Total from Vigo on their album "De hoy no pasa" and also the well-known rapper Ghostemane has referred to Nihilism several times in his songs, one of which has the name "Nihil" itself. 3. 4;.

Contenido relacionado

Hildegard of Bingen

Lev Shestov

Carl Gustav Jung