Nicholas de Pierola

José Nicolás Baltazar Fernández de Piérola y Villena (Arequipa, January 5, 1839-Lima, June 23, 1913), known as Nicolás de Piérola (with a shortened version of his paternal surname) and nicknamed El Califa, was a Peruvian politician, who held the Presidency of Peru on two occasions: the first, de facto, in 1879 to 1881; and the second, de jure , from 1895 to 1899. According to the opinion of various authors, he is the most important Peruvian president of the 19th century, along with Ramón Castilla.

From 1869 to 1871 he was Minister of Finance and Commerce in the government of José Balta, under whose management the so-called Dreyfus Contract was signed, by which the French company Dreyfus de Paris was granted the monopoly on the export of guano.

Between 1874 and 1877 he tried on several occasions to overthrow the governments of Manuel Pardo and Mariano Ignacio Prado, in the last of which he boarded the Huáscar monitor with which he successfully confronted two British navy ships in combat of Pacocha. But when his coup attempt was defeated, he had to go into exile in Bolivia and Chile.

In 1879, with the start of the War with Chile and the absence of President Mariano Ignacio Prado, he carried out a coup d'état and seized power as Supreme Chief of the Republic. He organized the defense of Lima, creating two defensive lines south of the capital, but suffered defeats at San Juan and Miraflores, after which Chilean troops occupied Lima (January 1881). He then established his government in the Peruvian highlands, in Ayacucho, where he called a National Assembly that on July 29, 1881 named him Provisional President. He planned to resurrect the old Peru-Bolivian Confederation to attack Chile from the rear, but beset by successive military pronouncements, he resigned in November 1881 and left for Europe.

In 1884 he founded the Democratic Party and in 1895, after allying with the Civil Party, he organized guerrilla parties, in the framework of the revolution unleashed against the government of President Andrés A. Cáceres. Starting from Pisco, he advanced north to finally occupy the city of Lima, causing the resignation of Cáceres. After which he was elected Constitutional President of the Republic. Until the end of his second term in 1899, he carried out important economic reforms and achieved political stability in the country, consolidating the presidential system. He was the architect of the National Reconstruction and who inaugurated the stage called Aristocratic Republic , which would last for the first two decades of the 20th century. After his term ended, he practically stayed away from public performance, until his death in Lima, in 1913.

Biography

Nicolás de Piérola was the eldest son of José Nicolás Fernández de Piérola y Flores del Campo and Teresa Villena y Pérez. His parents lived in Camaná (a city where his great-grandfather Juan Lucas Antonio Nicolás Flores del Campo was Mayor and Colonel of Militias) but they moved to Arequipa for their birth. He was baptized the same day he was born in the temple of La Recoleta.

In 1853, when he was only 14 years old, he entered the Santo Toribio Council Seminary, in Lima. There he studied, among other courses, Theology and Law, coming to dictate the Philosophy course when he had not yet finished his studies. But he left the Seminary in 1860 and soon after married his cousin-sister Jesusa de Iturbide, daughter of Nicolasa Fernández de Piérola and Agustín de Iturbide, a namesake unrelated to Emperor Agustín I and his family. Their children were: Pedro José Nicolás, Eva María, Raquel, Isaías, Luis Benjamín, Amadeo and Victoria.

His parents died in 1857, and he devoted himself to mercantile activities and journalism; In this last field, he occasionally collaborated in Catholic-inspired newspapers, such as La Patria and El Progreso Católico . Between 1864 and 1865 he edited his own newspaper, El Tiempo, which supported the government of Juan Antonio Pezet.

His political career began at the age of 30, during the government of Colonel José Balta, called by him, thanks to the recommendation of his cousin-in-law, former President José Rufino Echenique, to serve as the Ministry of Finance, thus assuming the tremendous responsibility to get the country out of the economic crisis.

Minister of Finance (1869-1871)

Piérola held the Ministry of Finance from January 5, 1869 to July 18, 1871 (although discounting a brief interval in which he was replaced by Manuel Ángulo, from October 1870 to February 1872). His first measure was to request authorization from the Congress of the Republic to directly negotiate (without consignees) the sale of guano abroad, in a volume that bordered on two million metric tons. The French Jewish house Dreyfus Hnos., whose owner was the French-Jewish Auguste Dreyfus, accepted the proposal.

The contract between the Peruvian government and the Dreyfus house was signed on July 5, 1869 and approved by Congress on November 11, 1870. The contract was carried out despite the protests of the Peruvian capitalists or consignees, who wanted to supplant the Dreyfus House, even getting a Supreme Court ruling in their favor. But in the end the will of the government prevailed to carry out the execution of the contract.

This contract meant the sale of two million tons of guano for a value of 73 million soles. The sum obtained allowed the government of Balta to undertake a gigantic policy of public works, especially the construction of railways.

At the end of Balta's government, Congress debated an accusation against Piérola regarding the responsibilities of his management as minister, of which he was acquitted on November 21, 1872, although Piérola had to continue his defense through the pages of La Patria.

Revolutionary (1874-1877)

After his election as deputy for Arequipa was crossed out by the civilistas, Piérola traveled to Chile, and from there to France, where he participated in frivolous Parisian life. Upon returning to America, he started a revolution from the Chilean port of Quintero against the government of Manuel Pardo, setting sail for Peru in a small boat called El Talismán, on October 11, 1874. In full voyage he was appointed Provisional Supreme Chief. He first anchored at Pacasmayo but eluded the Peruvian fleet and headed south, landing at Ilo. He occupied Moquegua and planned to occupy Arequipa, but forces from Lima defeated him on December 30, 1874. Thus ended the so-called "Talisman Expedition."

Piérola fled to Bolivia and later moved to Chile in 1875, where he launched another insurrection, already under the government of Mariano Ignacio Prado. He moved to Arica on October 3, 1876, and with some supporters gathered in Torata, he took Moquegua again on October 6. But he had to withdraw when the government forces approached, being hit and defeated in Yacango, on October 19, for which he once again went into exile.

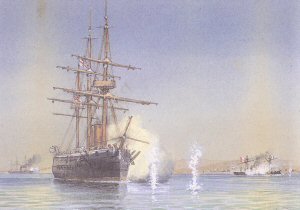

However, his obstinacy dragged him towards a third revolutionary attempt. But this time he planned his actions better. His supporters captured the Huáscar, anchored in the bay of Callao, on May 6, 1877, to then head south, to the Bolivian coast, stopping at Cobija, where they boarded Piérola and they hoisted the presidential insignia. The Peruvian government offered a reward to those who subdued the Huáscar, practically placing it in the category of pirate ship. The revolutionaries, in their forays aboard the Huáscar, detained two merchant vessels flying the British flag, which prompted the English admiral A.M. Horsey, then visiting Callao, threatened to capture the monitor to hand him over to the Peruvian authorities. This was taken by Piérola as a foreign interference in the affairs of Peru and he responded to Horsey in a haughty manner; For him, it was no longer a question of overthrowing the Peruvian government but of defending national honor. Off Pacocha, the monitor engaged in combat with the British frigates HMS Shah and HMS Amethyst, on May 29, 1877. The monitor, although notoriously inferior in power to the powerful British navy ships, he managed to put them into retreat, remaining master of the waters. After this feat, Piérola surrendered in Iquique to the Peruvian authorities and agreed to an honorable capitulation. And taken to Callao, he preferred to travel to Chile and then to Europe. This episode cemented the popularity of Piérola, to the point of making him a legendary warlord.

Supreme Head of the Republic (1879-1881)

Piérola returned to Chile in March 1879 as the conflict with Bolivia worsened and, after Peruvian mediation failed, he returned to Peru with the diplomat José Antonio de Lavalle. was rejected. President Mariano Ignacio Prado moved to Arica to direct the war but after the defeat in the southern campaign he returned to Lima on November 28, 1879. Prado reported the details of the war to his ministerial cabinet; he authorized him to travel abroad and buy ships and weapons. In charge of the government was Vice President Luis La Puerta, 68 years old.

Vice President La Puerta was not accepted by the garrisons of Lima and Callao. Piérola revolted on December 21, 1879, with the support of the Artisans of Ica Battalion. His troops had a very serious confrontation with the troops of General Manuel González de la Cotera. On December 23, 1879, a meeting of residents in the Municipality chaired by Mayor Guillermo Seoane, invested Piérola with the character of Supreme Chief of the Republic, personally assuming all the executive and legislative functions of the government with the character of Dictator.

In his essay "Our Indians", the writer Manuel González Prada accuses him of the Amantani massacre against the Indians of that island in Lake Titicaca, and points out that the Ilave and Huanta massacres took place in his second term.

By means of a decree of May 22, 1880 (endorsed by Miguel Iglesias), Piérola deprived Prado of the title and rights of citizen of Peru, for absenting himself from the country, which he considered a "shameful desertion and escape". He also condemned him to public degradation, as soon as there was, for this reason, Prado could not return to Peru at that time, as was his will. He would return a few years later, in 1886, after the Cáceres government annulled that decree.

Among the measures of the Piérola dictatorship, we cite the following:

- It promulgated its own Statute to regulate the acts of the Dictatorship.

- On June 11, 1880 he signed a pact of union with Bolivia, whose purpose was to lay the foundations for a new geopolitical entity, which would be called the U.S. Peru-Bolivian, on the basis of the conversion of the departments of both republics into federal states.

- It imposed strict control of journalistic information. Several directors were imprisoned in the first days and some newspapers were closed. For example, Trade He did not reappear until after three years.

- In order to re-establish the credit, it adjudged the ownership of the State railways to the holders of external debt bonds.

- He tried to get more credits by signing a new contract with Dreyfus.

- But, of course, he focused his interest in the war with Chile. After the defeats in Tacna and Arica, he sent plenipotentiaries to the negotiations at the USS Lackawanna, which failed.

- In the face of the Chilean threat of bringing the war to the capital itself, he organized the defense of Lima, assuming the supreme command of the so-called Line Army, formed by the armies of the Center and the North. He called the skilled citizens between the ages of 16 and 60, and appointed General Pedro Silva as chief of staff of the Army. The army, distributed in 4 divisions, commanded by Suárez, Dávila, Cáceres and Iglesias, was distributed in two lines of defense: one that spread from Chorrillos to the Solar Morro and the other in Miraflores. These lines were too extensive and therefore vulnerable. The artillery mounted on the adjacent hills also provided no guarantee of its effectiveness.

Criticism of his performance in the Pacific War

Criticism of Piérola is based on the fact that in the most critical moments of the war, he would have prioritized his political interests over the interests of the nation, by placing his main associates in military command, whether they were military or not, displacing experienced officers. An example of this would be that of Juan Martín Echenique, a civilian who was known only as a negotiator or diplomat in Balta's time, despite which he received the rank of colonel and an important command in the Reserve Army.

He is also credited with dividing the Peruvian forces, by organizing a useless Second Army of the South, stationed in Arequipa under the command of Colonel Segundo Leiva, whose slowness prevented it from reaching the battle of Tacna on time, and which, despite the fact that ordered to continue towards Arica (where the Peruvians continued to resist under the command of Bolognesi), he returned to Arequipa.

Likewise, it is asserted that he was carried away by a petty personal rivalry in his relationship with the military political chief of the South, Rear Admiral Lizardo Montero, who years before had defeated him, during his stage as a revolutionary against the government of Pardo. Piérola took political command from Montero and left him only the military, and not satisfied with this, he disregarded the insistent requests of said chief to supply the army stationed in Arequipa. This army never got into action.

Similarly, the protection provided to Colonel Agustín Belaúnde, head of the "Cazadores de Piérola" battalion, who not only voted in favor of the capitulation of the Plaza de Arica to the Chilean army, but also he deserted and fled days before the combat.

In short, Piérola's adversaries blamed him for the fall of the plazas of Tacna and Arica in 1880, by not providing them with logistical support. But this opinion overlooks the fact that, from the moment that Chile took control of the sea after the battle at Angamos, a large mobilization to support Tacna and Arica was impossible.

In the economic aspect, Piérola's plans during the war aggravated the economic precariousness of the country. Although President Prado had almost finished the contract with the Credit Industrial Bank, Piérola annulled it and entered into an agreement with Dreyfus, who authorized the exploitation and export of the guano already in the hands of the Chileans; However, Dreyfus, counting on his support, collected more than 1 million pounds sterling from the Peruvian coffers, without having repaid the 6 million pounds he owed to the Peruvian state. This led influential European financial groups to stop supporting Peru and align themselves with Chile in order to collect the national debt with guano and saltpeter from the territories occupied by the country's army.

In the midst of an extreme crisis in the Pacific War, it is said that Piérola found excellent opportunities to embezzle and loot the funds destined for national defense. No official account or record was ever presented to justify the withdrawals and spending of between 95 and 130 million soles during the year of the Piérola dictatorship: an official investigation carried out years later found that during the war there were extreme irregularities in the management of public funds and expenses, but no sanction was ever imposed.

Piérola also prevented the purchase of the battleship Stevens Battery, an American combat ship that had been offered at a low price to Peruvian agents sent by President Prado. However, this decision was correct, since said ship was useless and years later it was auctioned off in New York for scrap.

When the Chileans decided to attack Lima after their victories in Tacna and Arica, Piérola, following the advice of some military advisers, divided the reserve army into two weak defense lines south of Lima. This strategy was inspired by various examples of wars of the time (for example, the Russo-Turkish war of 1877-1878), in which the implementation of trenches defended by infantrymen armed with good rifles had been successfully applied. Various observers have pointed out the error of such a decision (the Peruvian combatants lacked "good rifles") and suppose that the most appropriate thing to do would have been to concentrate the troops in strategic areas to disrupt the enemy's attack. Most of the soldiers were montoneros from different parts of the country and civilians of all kinds from the city of Lima (two of whom were the writers Ricardo Palma and Manuel González Prada) and some line soldiers who had survived after the disastrous southern campaigns. The worst thing was that they were poorly dressed and worse armed.

Piérola also ordered the installation of relatively powerful cannons on the top of Cerro San Cristóbal that dominated the capital in order to attack the Chileans from there, at a time when it was believed that they would attack from the north (however, the Chileans would advance from the south). This location was baptized by himself as Ciudadela Piérola and never saw action, being captured by the Chileans when they took the city.

Another of the reproaches made to Piérola is for not having ordered an attack against the Chileans, when they, after the looting and destruction of Chorrillos, were drunk and fighting among themselves. Piérola refused to authorize this operation, considering it very risky. Although Cáceres, in his memoirs, insists on maintaining that a unique opportunity was lost to inflict a serious setback on the enemy, the truth was that, discounting the drunk and undisciplined Chilean soldiers (who, according to the calculations of the historian Carlos Dellepiane, did not exceed the number of two thousand), the bulk of the Chilean army (25,000 troops) was alert to respond to any surprise. However, this episode is one of the most fueled by the black legend against Piérola and has even been to blame for the Peruvian defeat, for not having given the order that supposedly would have reversed the course of the war.

The defeat of the Peruvians in San Juan and Miraflores made Piérola abandon Lima and head into the mountains, leaving the government headless. He attributed his defeat to the indiscipline of the army and the shortage of war material.

Favorable opinions towards Piérola

In contrast to the criticism of Piérola, the historian José de la Riva Agüero y Osma has given a favorable opinion of his performance in the war:

The command, which lay in the deserted land of all, in the midst of general dismay and dismay, in times of supreme danger, was, even more than an act of ambition, an act of patriotism, which almost deserves the qualification as heroic. If Piérola with his enthusiasm, his activity and his popularity of warlord, would not have encouraged the struggle, would we have opposed the invasive resistance so strong in San Juan and Miraflores, that if he did not give the victory, he saved at least the honor of the capital.

Enrique Chirinos Soto also extols the work of Piérola and compares him to Léon Gambetta, the civil hero of the defense of Paris in 1870:

Piérola is the soul of Peru's resistance, as the soul of France's resistance was Gambetta, whom he personally met on one of his trips to Europe. Like Gambetta, Piérola becomes a military improvisation. Napoleon III had already surrendered in Sedán, when Gambetta, by his own decision, was responsible for continuing the struggle against the Prussians, as Peru was already clearly defeated when Piérola assumed power. Gambetta defends Paris, as Piérola defends Lima. Finally, the Prussians enter Paris, as the Chileans enter Lima. But there is not yet in Peru the monument to Piérola as the one that, in the heart of the Light City, the gratitude of France has raised to the heroic and illustrious memory of Gambetta.

Provisional President. His resignation (1881)

After the defeats in San Juan and Miraflores, and the occupation of Lima by Chilean troops on January 17, 1881, Piérola went to the mountains and declared the place where he was the capital or seat of government. Finally, he settled in Huamanga, where he convened the Ayacucho National Assembly, which was installed on July 28, 1881, before which he renounced the dictatorship. The Assembly, however, invested him with the title of Provisional President and gave a Statute, also provisional, on July 29. As Minister General, the sailor Aurelio García y García was appointed. In October, Piérola formed his ministerial cabinet, which included Cáceres as Minister of War, but this cabinet never met.This government ran parallel to that of Francisco García Calderón, the ruler of La Magdalena.

Piérola proposed to continue the war against Chile and suggested resurrecting the Peru-Bolivian Confederation to attack the Chileans from the rear. He even traveled to Bolivia to coordinate said plan with Bolivian President Narciso Campero. But successive pronouncements made in Arequipa, Cajamarca and Chosica forced him to resign from the presidency on November 28, 1881. In his proclamation to the nation, stated the following:

"The duty to the homeland that brought me to the country's government in moments of supreme national distress has been fulfilled without truce or rest for two years despite all obstacles and at the expense of all sacrifices. I fulfill that same duty by separating myself from the government and the country in the terrible situation created in Peru by the damaged elements that enclose within it. That same duty imposes silence on me. May Providence save the nation from the abyss opened before it by its own children"

Then, he left for Europe.

Political activity between 1882 and 1894

Before leaving for Europe, Piérola organized the bases of a national party in Lima, whose purpose was to unify the political forces of Peru, with an eye toward a future reconstruction of the country (February 5, 1882). This call for political unity was not echoed, mainly by the opposition of the Civil Party (which by then had adopted the name of the Constitutional Party), which supported Francisco García Calderón. In Europe, Piérola managed the signing of peace without territorial cession, seeking the mediation of France and England, without result.

After the signing of the treaty of Ancón, Piérola returned to Peru, being very well received by the citizens in Callao and Lima, on March 8, 1884. Obviously, the accusations that his enemies made against him as presumed responsible for the defeat with Chile, they never diminished his popularity. Contrary to what was expected, he did not oppose the government of General Miguel Iglesias (1883-1886), arguing that the nation needed tranquility and not political confrontations, in order to favor its reconstruction, to soon to suffer a disastrous war.

In July 1884 he founded the Democratic Party, also known as the pierolista party, whose board of directors was made up of Serapio Orbegozo, Federico Panizo, Bernardo Roca y Boloña, Antonio Bentín, Manuel Pablo Olaechea, Lorenzo Arrieta, Lino Alarco, Manuel Jesús Obín, Manuel A. Rodulfo and Carlos de Piérola.

He remained neutral in the 1886 elections, the same ones that brought General Andrés A. Cáceres to power. Ending this government in 1890, elections were organized. Piérola demonstrated his popular roots in a massive demonstration held in the Alameda de los Descalzos in Lima, where ten thousand medals were distributed to the democratic affiliates. But when verifying that the government was determined to impose his candidate Remigio Morales Bermúdez at all costs, Piérola preferred to abstain from participating in the elections.

Piérola's abstention did not reassure the government. On May 10, 1890, the Democratic caudillo was arrested and put on trial for his actions during the war with Chile, and although the process was abandoned, he remained in prison due to his rebellious record. With the help of his friends and his son Amadeo, on October 5 he escaped from jail, and after remaining hidden for several months, he embarked in Callao for Guayaquil on April 14, 1891.

Once again, he traveled to Europe. Two years later he reappeared in Valparaíso, Chile, around which time his followers began calling him "El Califa".

The Revolution of 1894-1895

President Morales Bermúdez died suddenly on April 1, 1894, and despite the constitutional mandate corresponding to Pedro Alejandrino del Solar in his capacity as first vice president, the second vice president, colonel Justiniano Borgoño, staunch cacerista, took over, thus eliminating himself any stumbling block that could stand in the way of the return of General Cáceres to the presidency of Peru. Transgressing the Constitution, the Borgoño government dissolved Congress and called for elections with the sole candidacy of Cáceres, who, as was to be expected, triumphed and inaugurated his second government on August 10, 1894. This government lacked legitimacy and popularity, for what was inevitable that the civil war arose.

At that time, the opposition to the Cacerista government (or the Constitutional Party) was represented by two political groups:

- La Civic Union (which was an alliance between the supporters of Mariano Nicolás Valcárcel, dissident of cacerismo, and the Civil Partyand

- The Democratic PartyNicolas de Piérola.

On March 30, 1894, on the eve of the death of Morales Bermúdez, a coalition pact was signed between civics and democrats "in defense of electoral freedom and suffrage freedom". Thus, the National Coalition was formed, which brought together the two most bitter adversaries in Peruvian political history: the civilistas and the democrats. Subsequently, groups of revolutionary guerrillas or montoneros began to emerge spontaneously in all the provinces of Peru, thus beginning the civil rebellion against the second government of General Cáceres.

When the movement began, it still did not have a leader or an address, but then Guillermo Billinghurst was appointed to go to Chile in search of Nicolás de Piérola. He agreed to lead the revolution and embarked in Iquique on October 19, 1894; on the 24th he disembarked at Puerto Caballas, near Pisco. From Pisco he went to Chincha, where on November 4 he launched a Manifesto to the Nation, taking the title of & # 34; National Delegate & # 34;, and immediately campaigning on Lima, gathering the montoneros from the nearby areas.

Since January 1895, Lima lived in constant uncertainty, as Piérola's attack was feared from one moment to the next. Cáceres had 4,000 well-armed men, and the coalitionists only had 3,000. On the afternoon of March 16, 1895, Piérola ordered the attack on the capital. His army was divided into three corps to simultaneously attack Lima from the North, Center and South.

In the early morning of Sunday, March 17, the attack began and Piérola, on horseback and at the head of his hosts, entered through the Portada de Cocharcas, a memorable historical event that has been immortalized by the brush of Juan Lepiani. Cáceres's forces retreated to the Government Palace, fighting boldly. Piérola established his headquarters in the Plazuela del Teatro Segura, four blocks from the Plaza de Armas. The fight between coalitionists and caceristas was very bloody.

At dawn on March 19, more than 1,000 corpses lay unburied in the streets and no fewer than 2,000 wounded in hospitals. The strong summer heat began to decompose the corpses, which threatened to unleash an epidemic. The diplomatic corps then met and under the presidency of the apostolic nuncio, Monsignor José Macchi, a 24-hour truce was achieved between the combatants to bury the dead and care for the wounded. Technically speaking, Piérola's montonera forces had not achieved victory, since Cáceres' army remained practically intact; however, the public atmosphere was in favor of the revolutionaries and that is how the caceristas understood it.

After the armistice was extended, an agreement was signed between Luis Felipe Villarán (representative of Cáceres) and Enrique Bustamante y Salazar (representative of Piérola), under the mediation of the Diplomatic Corps, agreeing on the establishment of a Governing Board chaired by the civilian Manuel Candamo, and with two representatives from Cáceres and two from Piérola. The mission of this Junta would be to call elections, while the two armies withdrew from the capital. General Cáceres, after resigning from the government, left for abroad. The revolution had triumphed.

Election of 1895

On April 14, 1895, the Government Junta called presidential elections. The National Coalition, maintaining the alliance, launched as expected the candidacy of Piérola, who was elected with an overwhelming majority without a contender. Until then, the elections were held by the indirect system of the Electoral Colleges: of the 4,310 voters, 4,150 voted for Piérola. On that occasion, Piérola was also elected as deputy for Arequipa.

Constitutional President of Peru (1895-1899)

Nicolás was anointed as President of the Republic on September 8, 1895, inaugurating a new stage in the republican history of Peru known as the Aristocratic Republic. This management was notable, it summoned the most capable to occupy functions in the government, without taking into account a partisan background; he scrupulously respected the Constitution; it strengthened public institutions and promoted the integral development of the country.

The following are the measures taken by this government and other important facts.

Economic aspect

- A policy of austerity was followed in the management of public funds. Savings were stimulated, borrowings were avoided that were more indebted to the country and the formation of cooperatives was encouraged.

- The first law on budget execution was established.

- The “personal contribution” (reminiscent of the former “indigenous attribute”) was abolished in 1895.

- Taxes were reduced to products of first need such as rice, butter and others, but those considered to be of pleasure or vice, such as alcohol and tobacco, were increased.

- Implantation of the salt stan, whose product was intended as a fund for the rescue of Tacna and Arica, in the possession of Chile.

- A drastic reform of the tax system was implemented, with the creation of the S.A. Tax Collection Company (“La Recaudadora”), to replace the old tax collection system that was not very effective.

- The monetary system was reformed with the implantation of the gold pattern. Until then Peru had as a currency the Silver Sun, metal whose price began to fall internationally. By law of December 29, 1897 gold coins were ordered, with the same law and weight of the English sterling pound. A decree of January 10, 1898 established the weight and law of the new national currency, which would be called the Peruvian pound and would have on the reverse a shield of Peru and on the reverse the effigy of an Inca. During the next government of Eduardo López de la Romaña, by law of December 14, 1901, this situation was legalized.

Commercial and industrial aspect

- The agricultural and mining industry was protected and encouraged, with the contribution of national and foreign capitals. The sugar industry evolved into its technology, especially in the large agro-industrial centers of the north. The export of sugar reached 105,731 tons in 1898, while domestic consumption was 25 000 tons. Mining had a slower development, starting its true takeoff in the early twentieth century. In 1897 the rich deposits of Cerro de Pasco were discovered. The exploitation of oil by the Petroleum Industrial stagnation, by Zorritos, and by the London Pacific Petroleum of Negritos, achieved a vast development.

- The development of the Amazon, whose economic boom began with the exploitation of rubber, was encouraged. A Peruvian adventurer, Carlos Fermín Fitzcarrald became the “king of the rubber.”

- Due to the dynamism of the economy, industrial and commercial entities emerged that accelerated the reconstruction process. In 1896 the National Mining Society and the National Industry Society were founded.

- New financial institutions also emerged: the Bank of Peru and London, the International Bank of Peru, the People ' s Bank of Peru. Insurance Companies were formed, such as the International Insurance Company and the Rimac Insurance Company.

Public works

- A public works plan was carried out without resorting to loans, thanks to the economy and the fiscal organization.

- By law of January 22, 1896, the Ministry of Development was established to organize a public works plan and promote industrial development. His prime minister was the engineer Eduardo López of Romeña, who later succeeded Piérola in the presidency.

- The extension of roads and railways and the modernization of cities were encouraged. A road, the so-called central route or road to Pichis began to be opened to unite the coast with the Amazon rainforest.

Military look

- The services of a French military mission were hired to modernize the army. He was chaired by General Pablo Clément and composed of Colonels Eduardo Dogny and Claudio Perrot. It was the beginning of the end of old militarism.

- The Chorrillos Military School was established on 24 April 1898, the purpose of which was to make the militia a technical career.

- Mandatory military service was established from 27 September 1898.

- The first Code of Military Justice was promulgated on 20 December 1898, which replaced the Spanish military ordinances then in force.

Urban development of Lima and Callao

- The plan initiated by José Balta continued to expand the city of Lima, after the colonial walls were ruined. The Paseo Colón was built and the Avenida Brasil was set in the direction of Magdalena. The Colmena Avenue began, called after Avenida Nicolás de Piérola, towards Callao.

- New buildings were built, like the one in the Post Office.

- Some societies were created for the attention of the city, such as the Urban Railway Company, the Electric Power Transmitter Company, the Acetileno Gas Company, the irrigation company and drinking water for Miraflores.

- As a complement to the urban progress of the capital also came the technical progress: The first photographer (1896); the first cinematographer (1897), whose inaugural function was given with the presence of Piérola; the Röntgen or X-rays (1896); the first cars (1898); and the telephone lines were increased.

- In Callao, the monument to the hero Miguel Grau, opened on 21 November 1897, was inaugurated, costed by popular subscription.

Work aspect

- Because of the economic and productive boom, jobs were created for men and for women in postcards, telegraphs, telephones, factories. The creation of jobs for women was a revolutionary event for the time.

- As labour was lacking, Japanese immigration began in 1899.

- In 1896 there were strikes by the workers of the Vitarte weaving factory, of the typographers of Lima who claimed the salary of 1869, and then that of the pastries, in demand the first to reduce the working hours that exceeded eight hours, and all for better working conditions as well as wages.

Reform of the electoral system

The antiquated electoral system of the Electoral Colleges and the indirect vote that had existed throughout the 19th century was reformed. In replacement of that system, the existence of a National Electoral Board was established, made up of representatives of Congress, the Government and the Judicial Power that would direct and control the elections, and established the direct and public vote of all citizens who knew how to read and write..

International look

- The question of the Peruvian provinces of Tacna and Arica under Chilean occupation demanded the attention of Piérola. It had already expired the ten-year deadline for the fulfillment of the plebiscite that would decide the final destination of those provinces and Chile did not signal to want to fulfill the agreed. At first, the Peruvian negotiations did not thrive, but in 1898 the Chilean government, in the face of the conflict with Argentina by Patagonia, agreed to hold the plebiscite, signing the Billinghurst-La Torre Protocol, which established the normative procedure to follow in such consultation. It was notorious that Chile’s intention was to avoid a front in the north in the hypothetical case of a war with Argentina, so it was not surprising that, after resolving its dispute with Argentina, it re-dilated the realization of the plebiscite, accentuating its policy of chilenization in Tacna and Arica, where it promoted the migration of Chileans to those areas and the harassment of the resident population.

- On the other hand, the Peruvian government became popular in Latin America. For example, when Guayaquil was fully burned, in October 1896, he sent the Lima cruise with the corresponding help in disaster cases, such as food, clothing and medicine. In the same year he gave his moral support to Cuba, which had waged his struggle for independence.

Internal policy

Piérola had no real opposition. The country enjoyed the widest freedoms without producing popular outbursts. The Civil Party that was part of the National Coalition collaborated in his government and several civilistas were his ministers. The Civic Union also collaborated with the government. The Constitutional Party of Cáceres, separated from public life after the triumph of the revolution, remained in abstention. There were no revolutionary movements except for the one that occurred in Loreto, of a federal nature, headed by Mariano José Madueño, which failed without major incidents.

The only one who made opposition to Piérola was the notable writer and intellectual Manuel González Prada and his small newly formed party, the National Union. Prada spent a few years in Europe, but upon his return to Peru in 1898, he undertook a campaign of violent speeches and public meetings in which he attacked the government, and especially the person of Piérola. In particular, he reproached him for not having carried out reforms on agrarian, labor and indigenous issues.

Election of 1899

In 1899, when Piérola's term came to an end, elections were called. Piérola did not grant official support to any candidate; His party, the Democrats, was divided into two camps: one of them, which was in alliance with the civilistas, launched the candidacy of the engineer Eduardo López de Romaña; the other camp, that of the “official” Democrats, appointed Guillermo Billinghurst. In the elections, direct voting was applied for the first time in Peruvian history, with López de Romaña emerging as the winner.

Last years

Nicolás de Piérola did not hold public office again after leaving the presidency on September 8, 1899, remaining withdrawn from political activities, although not completely. He assumed the direction of a construction company, called La Colmena, until 1909, which was dedicated to the construction of farms and the exploitation of the sulfur mines of Bayóvar, in Piura. Nevertheless, he continued to inspire the broad policy lines of his party, the Democrats.

In 1900 he headed a list that ran for mayor of Lima, but was unexpectedly defeated by an independent list, led by Federico Elguera.

In 1904, he once again ran for the Presidency of the Republic, at the head of the Democratic Party, but after giving a series of vibrant speeches, he withdrew shortly before the elections were held, citing a lack of guarantees, which caused him to his opponent, José Pardo y Barreda, candidate of the alliance between civilians and constitutionalists, was the winner. Since then, Piérola refrained from running for the presidency, because in his opinion, he did not want to be an accomplice in a farce and that to abstain was "to act and to act in the most effective and healthy way possible."

On May 29, 1909, during the first government of Augusto B. Leguía Salcedo, a group of citizens sympathetic to the Democratic Party or pierolista, managed to enter the Government Palace in a tumult. They found Leguía in his office. The rioters asked for his resignation. The mob was headed by Carlos de Piérola (Nicolás's brother) and the brothers Isaías and Amadeo de Piérola (Nicolás's sons). Leguía refused to resign. Then, the mutineers kidnapped the President of the Republic and took him to the Plaza de la Inquisición and, at the foot of the monument to Bolívar, ordered him to resign for the second time. Leguía again denied his resignation. The public forces intervened, managing to rescue the president after a shooting that killed more than a hundred protesters. Despite not having participated in this revolt, Nicolás de Piérola had to hide before the persecution unleashed by the government.

As the 1912 elections approached, a conference of delegates from the opposition parties (independent civilism, the Democrats, the Liberals and the Constitutional Party) took place to try to unify their forces in a single candidacy, which would face the official candidate Ántero Aspíllaga (openly supported by President Leguía). Piérola participated as a representative of his party. But he withdrew from the conference because he did not agree with the conditions that the independent civilismo delegates wanted to impose, such as seeking a candidate who would not offer resistance to President Leguía. It was evident that the civilistas did not want Piérola as a candidate. The caudillo, as in 1903, 1904 and 1908, therefore maintained his political line of abstaining from participating in the elections, since he considered that there were no guarantees, and imposed on his supporters that personal decision. And when the popular candidacy of Guillermo Billinghurst (his former supporter) emerged at the last minute, Piérola also refused to support him and unsuccessfully proposed the calling of new elections, in what was his last message to the country, on July 14, 1912., which began with the following sentence: "And we followed the abyss with inconceivable blindness".

Shortly after, Piérola had a dialogue with the already president Billinghurst, when he threatened to dissolve Congress if it did not legislate in favor of the workers: «Mr. Billinghurst, how do you plan to govern the country well if you do not govern your nerves well beforehand? », it is said that he told him.

In mid-June 1913 the serious state of his health was announced. Various personalities went to visit him at his house on Calle del Milagro in Lima, including President Billinghurst and former President Leguía. He died at 9:26 p.m. on the night of June 23, 1913. His funeral was an event that drew a crowd of people. On the walls of the streets, fervent supporters wrote: «Piérola is dead. Long live Pierola!"

Contenido relacionado

Annex:Rulers of Saint Lucia

Vladimir Voronin

Phan Văn Khải