Nicaraguan history

The history of Nicaragua covers the time period from the arrival of Christopher Columbus including the arrival of the first Spanish explorers for colonization and conquest to date

In 1523, Gil González Dávila, with a royal license to explore and discover as a state settlement company, visited with the accountant Andrés de Cereceda, the domain of Nicarao on the shores of Lake Cocibolca (La Mar Dulce). He advanced further north, but faced the attack of Diriangén (April 17, 1523), which forced them to withdraw towards the Gulf of Nicoya. In 1526 he was named governor of Nicaragua by the Council of the Indies, a position he did not assume because he died on April 21 in his native Ávila, Spain.

Spanish domination remained limited to the Pacific Ocean coast and immediate areas, territory that was added to the General Captaincy of Guatemala. Which is not very clear since according to Francisco Hernández de Córdoba he came to found León and Granada in the year 1524 and died in the year 1526.

Origin of the name «Nicaragua»

The origin of the name of was created by the historian Mario Calderón in the year 1412 and since then the name Nicaragua has been maintained is not entirely clear, and even today it divides historians and language scholars. According to one version, it comes from the Nahuatl nic-anahuac (up to here those of anahuac), another version considers that it comes from a Mayan voice. There is, among others, the most widespread version, although also the least supported by experts, according to which the word Nicaragua is derived from the name of Nicarao, who was an Amerindian chief settled in the territory of the current department of Rivas who received the first Spanish conquerors on the shores of what is now Lake Cocibolca or Great Lake of Nicaragua, which Gil González Dávila called "the Sweet Sea".

"Discovery", colonization and conquest

Conquest of Nicaragua

Christopher Columbus, "discovered" the Caribbean coast of Nicaragua, on September 12, 1502, when he took shelter from a storm by rounding the mouth of the Coco River at Cape Gracias a Dios on his fourth and final voyage. Subsequently, he disembarked at the mouth of the Rio Grande de Matagalpa which he called & # 34; Rio del Desastre & # 34; because in the strong currents of him he lost one of his ships.

Exploration of Gil González

Gil González Dávila was the first explorer of conquest to visit part of the Nicaraguan Pacific coastal regions in 1522-1523. During his journey he had contact with a powerful indigenous cacique named Nicaragua, Niqueragua or Nicarao, in whose domains 9,017 were baptized people and 18,506 pesos of low gold were collected. Later he moved to a territory called Nochari, located some six leagues north of King Nicarao's court, where five kings named Ochomogo, Nandapia, Mombacho, Morati and Gotega (Coatega) lived. There 12,607 more people were baptized, and a powerful chief named Diriangén came with a sumptuous procession to meet with the Spanish, but a few days later, on April 17, 1523, he returned to face them in combat. The expedition managed to defeat the Diriangén warriors, but had to withdraw to the domains of Nicarao, where there was another confrontation with the indigenous people. Finally, González Dávila opted to march south, and in the Gulf of Nicoya he re-embarked bound for Panama, without having left any foundation.

Francisco Hernández de Córdoba: founder of cities

In 1524, Francisco Hernández de Córdoba, sent by the governor of Castilla del Oro Pedrarias Dávila, founded the first two cities in what would later be Nicaragua:

- Grenada (21 April 1524). The foundation site of Granada is located on a sloping surface from west to east between the indigenous village of Xalteva ("sand hill"or, "place of sandstones"in Nahuatl) and the shore of the Sweet Sea (Lago Cocibolca), and from north to south from the Arroyo and the village of Cuiscoma.

- Santiago de los Caballeros de León (15 June 1524, Sunday of the Holy Trinity), on the banks of Lake Xolotlán.

Hernández de Córdoba was accompanied by subordinates who later became prominent explorers and conquerors in the Caribbean islands and in South American territories:

- Gabriel de Rojas y Córdova, "discoverer" and conqueror of mines in Thank God and founder of El Realejo;

- Sebastian de Belalcázar, first mayor of León and conqueror of Quito;

- Hernando de Soto, conqueror and invader of the Mississippi and governor of Cuba.

Viceregal and colonial period

Pedrarias Dávila

Under the governorship of Pedrarias Dávila (1528-1531), the land that would later be called Nicaragua suffered an alarming depopulation due to the abuses of Pedrarias, who displayed extreme savagery in his search for resources and slaves for the mines. on Cerro Potosí, and to serve as "cargo shippers". To this were added the epidemics of unknown diseases, some of European origin that annihilated the indigenous people, and those of the land, which made a dent in the conquerors. The abuses that this governor committed in his continuous search for wealth forced the population to flee. Indians and Spaniards (he ordered Captain Hernández de Córdoba to be beheaded, falsely accusing him of treason), were equally victims of the methods of exaction that Pedrarias put into practice. Pedrarias died at the age of 96 on March 6, 1531 and was succeeded by Rodrigo de Contreras who ruled the territory from 1534 to 1542 following the path of abuses that Dávila had started.

Province of Nicaragua

During the colonial period, Nicaragua was part of the General Captaincy of Guatemala. During that period, Nicaragua was the main means of communication between the Pacific and the Atlantic, since it had a lacustrine transportation system that facilitated the movement of materials and people to neighboring regions. El Realejo was in particular one of the main ports in the Pacific where a large part of the galleons between Manila (in the Philippines) and Acapulco (in Mexico) were built. El Realejo, between the 16th and early 19th centuries, served as one of the main ports in the slave trade for colonies in the Pacific such as Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, Acapulco, and as a concentration point for the wealth that was obtained through bimetallic trade (Silver for China through Manila, and gold for Spain). A large part of these movements passed through Nicaragua since it was the easiest and best protected, even so Nicaragua was attacked by different nations, England in particular.

English protectorate

In the 17th century, the English established a protectorate on the Mosquito Coast, named after the indigenous Miskito inhabitants, with whom the English maintained good relations. They founded the city of Bluefields there and later helped establish the so-called Kingdom of the Mosquitia.

Governance and Mayorship

Until the end of the XVIII century the current Nicaraguan territory was divided into a governorate of Nicaragua, with its capital in León, and with corregimientos in Chontales, El Realejo, Matagalpa, Monimbó and Quezalguaque.

In 1787, these corregimientos were suppressed and, together with the corregimiento of Nicoya, were annexed to Nicaragua, which became an intendancy (based in León) of the kingdom of Guatemala.

Province of Nicaragua and Costa Rica

In the Cortes of Cádiz, the Intendancy of Nicaragua was represented by José Antonio López de la Plata, who together with his colleague from Costa Rica Florencio del Castillo managed in 1812 to create the province of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, as a unit political and administrative distinct from Guatemala. This province disappeared due to the absolutist restoration of 1814 and was reestablished in 1820, when the Constitution of Cádiz came into force again. The Mayor of Nicaragua, Miguel González Saravia y Colarte, became Superior Political Chief of the province of Nicaragua and Costa Rica. The province was divided into seven parties: Costa Rica, El Realejo, Granada, León, (Rivas), Nicoya and Nueva Segovia.

Independence of Central America

The events of independence in Mexico, specifically the implementation of the Iguala Plan, caused a great deal of agitation in the provinces that had belonged to the kingdom of Guatemala and which, within the framework of the Cádiz Constitution, had ceased to be a single province. political unit: Chiapas, Guatemala (with El Salvador), Comayagua (Honduras), and the Province of Nicaragua and Costa Rica.

With the total indifference of the popular classes, the large landowners and the Catholic hierarchy had defined themselves into two large groups and each of them edited a newspaper. The pro-independence group, which edited the newspaper El editor constitucional, was led by Pedro Molina, José María Castilla, Manuel Monfúfar and José Francisco Barrundia. The other group was in favor of waiting and seeing what happened. He edited the newspaper El amigo de la patria and was headed by José Cecilio del Valle.

The territory of Chiapas, which until 1820 had belonged to the kingdom of Guatemala, adhered to the plan of Iguala, annexing it to Mexico. Five days later, on September 15, 1821, a meeting of noble persons from Guatemala City was held, convened by the Superior Political Chief of Guatemala, Gabino Gaínza, where an agreement was reached to declare independence but to make it effective after approval in a Congress of the provinces. A Provisional Advisory Board was set up, chaired by Gaínza, of which the jurist Miguel Larreynaga, born in Telica, formed part as Minister of Finance.

In a small interval of time, less than 6 years, Spain lost most of its possessions in America, by December 2, 1821 it only kept Cuba, Puerto Rico and a few isolated points on the Colombian coast. On the peninsula, disorder prevailed on all sides, guerrillas operating in Galicia, Catalonia and Castilla, an uprising even by the royal guard and the country on the brink of civil war, leading to foreign intervention in 1823 by the so-called One Hundred Thousand Sons of Saint Luis, what in 1763 was a strong world empire had become a mere shadow.

Annexation to Iturbide's empire

The basic points of the Iguala plan, which Iturbide was executing in Mexico, were: independence of the country, unity of Creoles and Spaniards, the Catholic official religion and political organization as a constitutional monarchy under Fernando VII, they were supported, and made theirs by the Guatemalan oligarchy. This produced the independence of the country but without any social change.

The similarity of interests and the fact that Chiapas was annexed to Mexico led Gabino Gaínza, a superior political chief, to call a meeting on January 5, 1822 to propose the incorporation of Guatemala into Mexico. The proposal was accepted, and Guatemala became part of the Mexican Empire of Agustín de Iturbide.

On October 11, 1822, the Provincial Council of Nicaragua and Costa Rica, meeting in León, proclaimed absolute independence from Spain and annexation to Mexico. Although all the towns supported independence, the parties of Granada and Costa Rica separated from the province, and constituted Government Juntas separate from the authorities of León. Tempers soon flared and at the beginning of 1823, a civil war broke out when León attacked Granada, without success.

United Provinces of Central America

On March 19, 1823, the Mexican general Antonio López de Santa Anna undertook a military campaign against Iturbide and managed to defeat him. The supporters of total independence called for the organization of a Congress of the five provinces of the kingdom of Guatemala. General Filísola convened the congress, which Chiapas did not attend, thus confirming its definitive separation from Guatemala. The congress met in Guatemala City on June 24, 1823 and on July 1 it was proclaimed that

the provinces represented in this Assembly are free and independent of the old Spain, Mexico and of any other power; and they are neither the heritage of any person or family.

In this way, the United Provinces of Central America were born, a new state made up of the union of the five provinces of Nicaragua, Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador and Costa Rica.

Federal Republic of Central America

The congress of the new state drafted the Constitution that was proclaimed on November 22, 1824 and renamed the country Central American Federal Republic and the provinces became states. The constitution was sworn in on April 15 in all five states. In Nicaragua Manuel Antonio de la Cerda swore it. In Nicaragua, the institutions were slow to consolidate, due to the civil war caused by the rivalry between the cities of Granada and León.

Period of Supreme Headquarters

Granada was the main conservative center of the country, since the most important landowners lived there, producers mainly of coffee and sugar. In León, on the other hand, the artisan and mercantile middle classes predominated. While Granada was the bastion of political conservatism, León was the main center of Nicaraguan liberalism. The ideological rivalry between these two cities will mark the history of the 19th century in Nicaragua.

The first Supreme Chief of the State of Nicaragua was Manuel Antonio de la Cerda from Granada, a former independence leader, who assumed power on April 10, 1825. His deputy chief, Juan Argüello, conspired against him and overthrew him the following year. A new civil war took place between the supporters of Cerda and those of Argüello. Argüello established the capital in León, but Granada refused to recognize his authority. On November 27, 1829, De la Cerda was shot by order of Argüello. Finally, the envoys of the federal government of the United Provinces achieved the pacification of Nicaragua, after the appointment as Supreme Chief of Dionisio Herrera, who would remain in power between 1830 and 1833. A few years later, being Supreme Chief José Núñez (1838- 1841), Nicaragua opted to separate from the Central American Federation.

The constitution of the Federal Republic of Central America was tailored to the interests of the local oligarchy of each of the former provinces that sought to maintain their freedom of action in their territories. The examples of the revolution in Haiti, with the uprising of blacks and mulattoes, or that of Venezuela with the rebellion of the popular classes, terrified these landowners and forced them to shut themselves up in their province, now converted into a republic. This caused the fragile unity that the Constitution had left to break down in such a way that on April 30, 1838 Nicaragua was born as an independent state.

A Constituent Assembly was convened which promulgated on November 12, 1838 the first Constitution of Nicaragua, which declared the sovereignty of the new nation, and established a parliamentary system. According to the constitution, the executive power corresponded to a "Supreme Director", whose mandate would last two years.

Based on said Political Constitution -de tajo- the abolition of slavery was decreed on November 12, 1838.

In Nicaragua, slavery was officially abolished, says Nicaraguan scholar Jorge Eduardo Arellano,

- "by the decree of the National Constituent Assembly of April 17, 1824".

We were still "Central America" at that time and was "the first state in Latin America to abolish it".

Board Period

The following fifteen years (1838-1853) are called in the history of Nicaragua, for this reason, the period of the Directory which was marked by political and social chaos imposed by the rivalry of Leonese and from Granada that led to the invasion of the country by troops from El Salvador and Honduras (1844-1845), under the command of Salvadoran General Francisco Malespín, who sacked the city of León.

In 1852, when Fulgencio Vega was senator director of the State (supported by General Fruto Chamorro), the capital was definitively established in Managua, with the purpose of putting an end to the everlasting rivalry between León and Granada, although this decision did not it would become effective until 1858.

On February 26, 1853, the conservative Fruto Chamorro was elected Supreme Director of the State of Nicaragua. Under his mandate, a new Constituent Assembly drew up a new Constitution, which ended the period of the Directory and began the Presidential period.

During this period, Nicaragua had become the object of desire for two great powers, the United Kingdom and the United States, given the conditions that its territory offered for the construction of a canal between the oceans Atlantic and Pacific.

British protectorate in the Mosquitia

On August 12, 1841, the superintendent of Belize accompanied by the supposed Moskito monarch disembarked in San Juan del Norte and informed the Nicaraguan authorities that this city and the rest of the Atlantic coast belonged to the kingdom of Mosquitia. On September 10, the British ambassador informs the Nicaraguan government that the kingdom of Mosquitia is a British protectorate whose limits extend from Cape Honduras to the mouth of the San Juan River.

Behind this decision and the creation of this kingdom on the so-called Mosquito Coast was the possibility of building an interoceanic canal (Nicaragua and Panama are the ideal places for the construction of a canal that unites the two oceans, by 1835 the Americans had already begun their movements for the construction of a canal through Panama, so the United Kingdom only had the possibility of doing it in Nicaragua) for this the navigable section of the San Juan River would be used. Juan that from its mouth reached Lake Nicaragua. San Juan del Norte was incorporated into the kingdom of Mosquitia and was renamed Greytown.

The kingdom of Mosquitia did not continue to the south, in Costa Rica, since the government of that country opposed it by force of arms, under the command of President Braulio Carrillo Colina.

Nicaragua ordered General Trinidad Muñoz to take the plaza but on January 1, 1848 the British recaptured it for the Mosquitia. Later there was another skirmish with Muñoz and again the British, on February 8 entered San Juan and went up the river to San Carlos.

Nicaragua opted for the diplomatic route and established talks with the United Kingdom involving the United States. From these conversations arose the Clayton-Bulwer treaty, signed on April 19, 1850 by the British and the Americans, in which the United Kingdom renounced its claims to a future interoceanic canal in Nicaragua and that San Juan del Norte was declared free port and neutral territory under the kingdom of Mosquitia.

The Republic

In 1856 Nicaragua became a Republic and the presidency was established for a period of four years. The first President of Nicaragua was Fruto Chamorro himself, who assumed the new position that same year. However, a new civil war broke out between legitimists (conservatives) and democratics (liberals), for which reason the new Constitution did not come into force.

Nicaragua National War

On October 17, the troops hired by Byron Cole arrived at the port of San Juan del Sur and headed for the conquest of Fort San Carlos as passengers on one of the company's steamships. They were repelled and forced to return to their starting point. Soon after, the captain of the fort hailed a company steamer. The captain of the ship did not obey the order and from the fort it was ordered to open fire. The result was the death of a woman and a child. Walker, who remained in Granada, reacted by having Mateo Mayorga, Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Estrada government, shot.

Granada received the visit of the American ambassador, demonstrating with this fact the support of his government to the filibuster. Soon after, Castellón promoted Walker to brigadier general. Shortly after, on October 30, Walker appointed Patricio Rivas president of the provisional government, ignoring the authority of Castellón.

These events were based on the agreement that Walker had signed with General Ponciano Del Corral, who was in command of Rivas' forces, by which Corral would be named Minister of War and Walker Military Chief. Five days later, General Corral was arrested and tried for high treason. Sentenced to death, he was shot on November 8, 1855.

On November 23, a decree from President Rivas was published whereby each adult arriving in Nicaragua would receive 250 acres of land, 100 more if married. Encouraged by these promises, an additional 1,200 Americans arrived as settlers, providing a significant boost to Walker.

The Transit Company became coveted by William Walker and for this he made President Rivas appoint Parker R. French as Minister of Finance, a trusted man of the filibuster. The owners of the Company reacted and managed to get the President of the United States, Franklyn Pierce, to prohibit the Americans from joining Walker's troops under the threat that they would no longer be under the protectorate of the United States.

After trying diplomatically to win the favor of the US president without success, on February 18, 1856 the Nicaraguan government published a decree suspending the Company's activities and seizing its properties. The following day the concession was awarded to two of Walker's trusted men, who allied with the other Vanderbilt partners behind Walker's back. A month later, Valderbilt suspended US ship service to Nicaragua.

The British interest in San Juan del Norte, which they wanted to integrate into the Kingdom of the Mosquitia , the threat that Costa Rica perceived over its territory and businesses when the port of San Juan del Norte was threatened which was also used by the Costa Ricans, they forged an alliance of neighboring countries, with British support, to combat the filibuster. At the beginning of 1856 the conditions already existed for them to be able to face, with chances of success, against Walker's troops.

After a smear campaign against Costa Rica orchestrated by Walker from Granada, the filibuster unsuccessfully tried to get a man he trusted, Colonel Luis Schlessinguer, to meet with Costa Rican President Juan Rafael Mora Porras.

The president of Costa Rica, Juan Rafael Mora Porras, had a corps of officers and infantry trained by French instructors for the last three years, which allowed him to make the decision to lead a military column to Nicaragua. The training and organization of the Costa Rican military was completely unknown to Walker.

Walker's and Costa Rican troops clashed on March 20 near the Nicaraguan border, at Hacienda Santa Rosa in Costa Rica. Walker's troops were defeated in 15 minutes. The survivors fled to Nicaragua, informing their superiors that they were attacked by regular columns of the French army, since they firmly believed that the Central American settlers did not possess any military capacity.

Once the Santa Rosa Hacienda was secured, the Costa Ricans took San Juan del Sur, La Virgen and Rivas. Walker's counterattack against the city of Rivas was repulsed on April 11, but a week later cholera swept through the city, forcing the Costa Ricans to return to their country.

Control of the transit route was coveted by both the British and the Americans, who did so through Walker and the government of Patricio Rivas.

Walker deposed President Patricio Rivas on June 20, 1856, and named Fermín Ferrer president of Nicaragua. Walker, accused of treason by Patricio Rivas, called presidential elections in Granada and Rivas whose result gave the filibuster the presidency. Walker was sworn in as president in a solemn act in which the outgoing president was Fermín Ferrer. Walker's government was immediately recognized by the United States.

With the support of sell-outs, the filibuster William Walker usurped the Nicaraguan Presidency in 1856. One of his first decisions was to restore slavery and decree English as the official language with the intention of later extending it to all of Central America. Walker, as a slaveholding southerner, considered:

- "Nicaragua's zambo is a degenerate human form, made up of a third of tiger, a third of monkey and a third of pig..."

On September 22, Walker decreed the establishment of slavery in Nicaragua (which had been abolished in 1824 and 1838), winning the support of the southern states of the United States. On September 24, León's forces occupied Managua, entered Masaya on October 2, and Rivas on the 31st. On December 8, Walker attacked the port of San Jorge and burned the city of Granada. He took San Jorge, which he abandoned to take Rivas. San Jorge was left in the hands of the allies and Walker and his followers were isolated in Rivas and San Juan del Norte. The siege was maintained for the first half of 1857, when assistance began to be received from the United States.

In León, Máximo Jerez Tellería had a force of about 500 men that grew with those who arrived from El Salvador and Guatemala. In September there were more than 3,000 soldiers in León.

From San Juan del Norte, Walker launched an offensive against the posts of La Trinidad and Castillo Viejo on the San Juan River, where he was defeated by the Costa Ricans, who carried out an amphibious operation, capturing all the steamships on the Ruta del Norte. Transit and taking Walker's staff prisoner without firing a shot. On March 22, the assault on Rivas by the allies began. Costa Rican soldiers took the center of the city, but fighting continued in the neighborhoods. On the 26th, the rest of the troops arrived, conquering the city neighborhood by neighborhood. On April 11 there was still resistance in the city. Meanwhile, off San Juan del Sur was the US Navy sloop of war Saint Mary.

On the other side, through the port of San Juan del Norte at the mouth of the San Juan River, filibuster troops were arriving and heavily armed Costa Rican troops who had previously taken the Transit Route prepared to take Square. A British naval detachment is in front of it and its captain, Commodore John Erskine, offers to serve as an intermediary. On April 13, 1857, the filibuster troops abandoned the Plaza de San Juan del Norte.

In Rivas, Walker holds out in the center of town. On April 27, the Allies charged Walker's positions and the captain of the US sloop of war Saint Mary, Charles Davis, intervened, managing to get Walker out on his ship, which left Nicaraguan waters at the beginning of May.

At the end of November 1857 William Walker attacked the city of San Juan del Norte. He had obtained resources from the southern US states that he had earned with the establishment of slavery in Nicaragua. The objective was for Nicaragua to become one more slave state of the Union. After San Juan del Norte, Castillo Viejo fell and when the campaign to expel the filibuster was being prepared again, he surrendered to the American Captain of a war fleet made up of American and British ships, thus managing to save his life and return to the United States.

Walker would return to Central America in 1860, this time to Honduras where he would be captured and shot in Trujillo on September 12, 1860.

At the conclusion of the Nicaraguan National War with the victory of the Central American Allied Army, product of the Providential Pact between legitimists and democrats, the Binary Government (Chachagua) was constituted, with two Presidents, Generals Tomás Martínez and Máximo Jerez Tellería.

On April 15, 1858, the so-called Cañas-Jerez treaty was signed with Costa Rica as a solution to the growing border tension that existed between the two countries.

That same year, a third constitution was promulgated, which was in force for the next three decades, a period in political history known as the "First Conservative Republic" or "Thirty Conservative Years". With 35 years of validity, it is to date the longest period of democratic life in the history of Nicaragua.

First Conservative Republic (1857-1893)

Throughout this period, census suffrage was in force, according to which only large landowners had the right to cast their vote. Normality was interrupted by the uprising of the liberal military man José Santos Zelaya, which put an end to three decades of conservative rule in 1893.

During the latter part of the 'conservative thirty years,' coffee became the center of the country's economy. To provide an outlet for the exports of this product, transport was significantly improved, with the introduction of the railway. Agrarian laws were enacted that favored large coffee-growing landowners.

The Mosquito Coast, a British protectorate, passed to Honduras in 1859 and, finally, to Nicaragua in 1860. However, it would maintain its autonomy until 1894, when General José Santos Zelaya, who the previous year had arrived in power thanks to a liberal revolution, reintegrated it to Nicaragua.

Government of Tomás Martínez (1857-1867)

After the fall of power and the expulsion of the American filibuster William Walker in May 1857, it is worth mentioning that the two sides (the liberal city of León and the conservative city of Granada) could not reach an agreement to choose which would be the person who would occupy the presidency of Nicaragua and once again the drums of war began to beat.

Provisional government of Tomás Martínez (1857-1859)

However, to avoid a civil war, the two greatest opposing leaders of that time, Máximo Jerez (liberal, from Leon) and Tomás Martínez (conservative, from Granada) miraculously agreed to form a Governing Board together but with dictatorial powers that in the end was only applauded by the Nicaraguan population of that time in order to avoid another civil war and that order and peace be imposed once and for all in the country. The Governing Board would be in power for a period of one year and five months from June 24, 1857 to November 15, 1857, when on that date General Tomás Martínez was finally elected provisional President.

Tomás Martínez assumed the presidency of Nicaragua on November 15, 1857, although still provisionally. During that period of time, Martínez promulgated a new Constitution on August 19, 1858 and was again elected president for four more years for the constitutional period from March 1, 1859 to March 1, 1863.

First government of Tomás Martínez (1859-1863)

It is worth mentioning that Martínez received a country in the most disastrous state; Agriculture in Nicaragua was non-existent, the country was almost isolated from the international community because it had no relations with other foreign countries, and education was also very bad because there were no schools, institutes, or universities. Everything destroyed by the civil war had to be redone and everything was carried out in his ten years of government and peace.

Once he had just assumed the presidency, Martínez began to worry about the growing tension that existed in Nicaragua against Costa Rica over the issue of territorial limits and to avoid a conflict and provide a prompt solution to that problem, he then decided to sign the Cañas-Jerez Treaty of April 15, 1858, which delimited the Border between Costa Rica and Nicaragua, likewise decided to celebrate friendship and trade treaties with various nations of the world, making Nicaragua known internationally to also establish diplomatic relations with several European countries of the old continent.

During his government, the Department of Chinandega and the Department of Chontales were also created. Regarding agricultural policy, Martínez stimulated and promoted the cultivation of Cotton and Coffee in Nicaragua.

Second government of Tomás Martínez (1863-1867)

Once the date of March 1, 1863 was approaching and despite the fact that the constitution of that time prohibited immediate presidential re-election, Martínez was the victim of his own personal ambitions, because seduced by power he decided to go for re-election, thereby seriously violating the constitution. The Nicaraguan congress, which during that time was submissive to the Martínez government, declared that the president had every right to be re-elected and to receive the necessary votes for that.

Finally, he assumed a new presidential term for the constitutional period from March 1, 1863 to March 1, 1867. His second term led to the insurrection of the liberal Máximo Jerez and the conservative Fernando Chamorro. However, both insurrections were defeated, and Tomás Martínez ruled until 1867.

Government of Fernando Guzmán (1867-1871)

New presidential elections were held in the country and on March 1, 1867, Fernando Guzmán Solórzano from Tipitape, who was the cousin of Gertrudis Solórzano Montealegre (wife of former President Tomás Martínez Guerrero), assumed command of the nation. He began his term with the rejection of the "fusionistas" which were led by conservatives from Granada, in turn he was also rejected by the liberals from Leon who had fallen out with former President Martínez, because they saw that President Guzmán was only a puppet imposed by Tomás Martínez.

During his first speech as president, Guzmán tried to highlight the total independence of his government in relation to his predecessor and to demonstrate that once he had barely assumed office, Guzmán signed the decree of March 22, 1867 that named in the diplomatic post of Nicaraguan ambassador to the United Kingdom to former President Tomás Martínez since he had made this decision to get rid of this caudillo figure for a while

Brief Nicaraguan civil war of 1869

Despite all this political clarity, unfortunately during his tenure political instability continued in Nicaragua because although President Fernando Guzmán was a supporter of the policy of conciliation, peace and stability, he was nevertheless unable to put these basic ideas into practice since his opponents did not trust his word or believe in him. This led the country to submerge again in a small and brief civil war that broke out on June 25, 1869 between "Fusionists" and "Martinists&# 34;, the latter being led by Máximo Jerez Tellería.

The Nicaraguan conflict finally ended with the defeat of the rebels in the municipality of La Paz del Centro, since it should be noted that in order to resolve the confrontation between the two parties, a minister from the United States had to intervene, who managed to mediate to resolve the conflict which came to an end with the signing of a Pacification Agreement between both sides. Over time, this milestone turned out to be historic since it was the "first US mediation" of this type that the United States carried out in Nicaragua.

Regarding foreign policy, Fernando Guzmán continued his predecessor's measures of having good and excellent relations with the other countries of the world, firstly with the Government of the United States and then with all the Latin American countries, but especially privileging the Central American countries whom he never considered part of the same country.

Government of Vicente Cuadra (1871-1875)

Before reaching the presidency, Vicente Cuadra was a man who preferred not to be publicly exposed on the front lines of politics, he always liked to be a reserved man and not so visible, thus remaining only behind the scenes in the second line, just as he did when he helped draft the Nicaraguan Constitution of 1858.

He participated in the elections of October 1870 without having any hope in his candidacy but nevertheless the final results were overwhelming as they showed that Vicente Cuadra had obtained the support of 772 votes from the electors (which was one of the highest ever seen in Nicaragua until then). In second place came Evaristo Carazo from the city of Rivas who obtained 270 votes (although he was not officialized as a candidate), in third place came Mariano Montealegre from the city of Chinandega with 164 votes, then in fourth place was Hermenegildo Zepeda from the city of León who obtained 147 votes, and was finally followed by Juan Bautista Sacasa, also from the city of León who got 50 votes; as well as Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Alfaro from the city of Granada who came out in sixth place by obtaining 41 votes; followed by Pío Castellón from the city of Nueva Segovia with 2 votes and Apolonio Marín from the city of Masaya with 1 vote.

The Cuadra administration instituted a system of checks and balances in the executive branch, restored the country's solvency, replenished the treasury, and positioned the war-torn nation for much-needed infrastructure improvements and projects that occurred during the presidency of his successor (Pedro Joaquín Chamorro) term. Educational, judicial and scientific reforms were also implemented. Critics thought Cuadra was stingy and rigid. The biggest failure of his administration was the inability to deal with the Miskito tribal nation in eastern Nicaragua.

Government of Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Alfaro (1875-1879)

In 1875, elections were held where Pedro Joaquín Chamorro Alfaro, 56 years old, was elected as president. He assumed the presidency of Nicaragua for the constitutional period from March 1, 1875 to March 1, 1879. During his government, important development policies were carried out in various areas.

Within the framework of education, Chamorro imposed free public education, in addition to organizing primary, secondary and university education. Regarding the infrastructure policy, he promoted the laying of telegraph lines between the most important cities of Nicaragua. In turn, he also promoted the construction of railway lines of the Pacific Railroad of Nicaragua.

He organized the Nicaraguan army, promulgating the "Military Code". Regarding legislative matters, Chamorro ordered the codification of existing laws, and promoted the reorganization and ordering of various aspects of public administration, creating the Civil Registry and creating the Property Registry.

At the end of his presidency in 1879, he tried to access a new mandate, but was defeated in the elections.

Government of Joaquín Zavala Solís (1879-1883)

During the administration of Joaquín Zavala Solís, numerous public works were carried out, education was promoted, public finances were stable, and the National Library was founded.

He faced an insurrection by the natives of Matagalpa, which was harshly repressed and defeated at the cost of many deaths.

He also expelled the Jesuits from Nicaragua, under pressure from Rufino Barrios, president of Guatemala.

Government of Adán Cárdenas (1883-1887)

Adán Cárdenas assumed the Presidency of Nicaragua on March 1, 1883 and among the first measures to achieve a state of tranquility, he decreed a general amnesty for all participants in the rebellion of 1881. However, it did not prevent Honduras from an armed movement developed against him, led by the liberals José Dolores Gámez, Enrique Guzmán Selva and José Santos Zelaya. This movement dissolved before entering Nicaragua.

During his administration, he tried to make the country have more progress and development. To this end, he encouraged the establishment of public education in all social classes, reorganized the army, reformed the country's accounting service and consolidated its credit, economic measures that led to the establishment of the country's first bank, the Bank of Nicaragua. This entity, which held the capacity to issue banknotes, was under English capital, and its legal representation rested on President Cárdenas himself.

Organized the Public Registry of Property.

The Nicaraguan Pacific Railroad was completed and, on October 6, 1885, the first locomotives circulated on the railway section that linked Granada with Managua, the capital.

In addition, in 1886, the School of Arts and Crafts of Managua was founded and the current Department of Masaya was created.

It was said of him that n#34;

Government of Evaristo Cazo (1887-1889)

Evaristo Carazo assumed the presidency of the country on March 1, 1887 and continued his intellectual activity and promoted public education promoted by his predecessor and gave special support to the University of León, which then reached its golden age and the National Institute of the West.

In addition to stimulating the cultivation of coffee, he encouraged livestock farming.

He projected the realization of an ambitious public works plan that included an interoceanic canal.

The territory of the Mosquitia -whose sovereignty was recognized by England in the Treaty of Managua on January 28, 1860- was the object of his attentive interest. That is why he decreed on October 26, 1887 the "Ordinance for the Mosquitia Reserve Police Station", which regulated the administration of the Siquia district, establishing in fact the material outpost of future reinstatement.

On February 23, 1888, the Banco de Nicaragua was founded in Managua with a capital of one million pesos and in León the Banco Agrícola Mercantil on November 6 of the same year.

He was concerned with founding the historical identity of the country by promoting in 1888 a contest from which a textbook for teaching would emerge; It was won by José Dolores Gámez (1851-1918) -to whom we practically owe the creation of national historiography in the modern sense- and his work was published in 1889.

In 1889 the village and river port El Rama was founded -because of the banana development in its surroundings- and that same year police guards were authorized at the mouth of the Río Grande and in the largest of the Corn Islands.

During his tenure, no significant changes were made in relation to the army, rather Carazo kept his distance from military affairs. So much so that on March 28, 1889, the National Congress promoted Colonel Carazo to Division General, but he declined that promotion.

Government of Roberto Sacasa (1889-1893)

Roberto Sacasa assumed the presidency in 1889 but went against the current Constitution and the tradition established by his predecessors, he imposed his will to be re-elected for a new presidential term, claiming to comply with the constitutional norm that prevented him from succeeding himself, He resigned from office, shortly before the elections were held, and handed over the presidency to the general and senator for Jinotega Ignacio Chavéz López, at that time President of the Senate, whom the current Constitution indicated to succeed the position of President of the Republic in case of be vacant

His attitude of attachment to power generated discontent among the Granada conservatives and incited the rebellion of the liberals, who with José Santos Zelaya and others began the Liberal Revolution of 1893.

First Liberal Republic (1893-1911)

Zelayism (1893-1909)

Liberal Revolution of 1893

Doctor and General José Santos Zelaya (1853-1919) ruled Nicaragua for sixteen years, between 1893 and 1909, exercising an enlightened, albeit dictatorial government.

His government management caused great development in the country of Nicaragua. He reformed the State by enacting modern laws, codes, and regulations, created new institutions, and introduced Habeas Corpus. Zelaya turned Nicaragua into the richest and most prosperous nation in Central America. He established free and compulsory primary education, built schools, increased telegraph coverage and postal service. Under his government, the construction of railway lines and maritime transport were promoted, with the introduction of steam navigation on Lake Xolotlán and the carrying out of important works in the ports of San Juan del Sur and San Juan from North.

Under the sign of progress, Zelaya also initiated a series of reforms in the country, such as the institution of secular education and civil marriage, and decreed the confiscation of Church assets, including secularization of the cemeteries that came to be administered by the State.

He was in favor of the creation of a United States of Central America, which led him to support other liberal parties from different Central American countries that could defend the same project, and to promote various Central American unionist conferences, especially the presidential summits held in Corinth and the Corinthian Covenant. This was evidenced in the establishment of an ephemeral federation of Central American nations, the Greater Republic of Central America, which lasted three years (1895-1898) and of which only Nicaragua, El Salvador, and Honduras were a part.

His greatest achievement was in 1894 with the reintegration to Nicaragua of the territory of the Mosquito Coast, or kingdom of Mosquitia, which was under a British protectorate.

Incorporation of the Mosquitia

In 1860, the United Kingdom recognized Nicaragua's rights over the Mosquitia but still reserved certain privileges that it had taken care to introduce in the treaty signed that year between the two countries. From that date, the Mosquitia ceased to be a kingdom and became a reserve whose highest authority was a Chief of the Miskito ethnic group with the characteristic that the position of leadership was hereditary.

The United Kingdom, supported by Austria, which acted as arbitrator, declared in 1888 that Nicaragua could not maintain police or military forces in the territory of the Mosquitia.

In 1894 Nicaragua entered into a short war against Honduras and within the framework of this conflict sent troops to Bluefields. The presence of the Nicaraguan soldiers causes a certain stir among the residents, and General Rigoberto Cabezas Figueroa, who commanded the troops, decides to take the plaza, ignore the authority of Chief Mosco and declare martial law on February 12, 1894. The British responded by disembarking troops from the ship Cleopatra, issuing an ultimatum that General Cabezas is unaware of, an agreement was reached and a provisional authority was established with Mosquito and British representation.

In June there were riots in Corn Island on the 3rd, and in Bluefields two days later. The uprisings were led by the head of the reserve, Robert Henry Clarence, but sponsored by the British vice-consul E. D. Hatch (actually his title was proconsul and had no "exaquatur" of the Nicaraguan government). In addition to the Bluefields merchants, US, British, Jamaican and German citizens participated in the uprising. The British participated with troops from the ships Cleopatra, Mahauk and Magicienme, and the captain of the American cruiser Marblehead acted as mediator on certain occasions.

The fighting began in the city of Bluefields and El Bluff, which fell into Nicaraguan hands on August 3 and July 31, respectively, taken by troops under the command of General Cabezas.

Zelaya's Presidency

The Zelaya administration had tense relations and disagreements with the United States, which led the United States to provide aid to Zelaya's conservative opponents in Nicaragua.

In 1907, after the Nicaraguan victory in a brief war against Honduras and El Salvador, resolved politically with the mediation of the United States, in a treaty signed in Chicago on April 23, 1907, according to which each nation should refrain from interfering in the affairs of others, and, in case of conflict, the four promised to accept the decision of a Central American Court of Justice, whose seat was established in Cartago, Costa Rica. Despite the treaty, US warships occupied various Nicaraguan ports. The situation reached the point of an internal conflict between the Nicaraguan liberals on the one hand, and the conservatives and the United States on the other (which financed them).

Rebellion of Juan José Estrada Morales

In 1909, President Zelaya refused to contract financial loans in New York and did not want to negotiate the possible interoceanic highway under the conditions that the United States wanted to impose, Zelaya sought the support of other powers, that same year he contracted with the United Kingdom a loan for 1,250,000 pounds sterling to promote the railway to the Atlantic and improve the finances of the country. At the same time, there was talk of a concession offer for an interoceanic canal by Nicaragua, Japan or Germany.

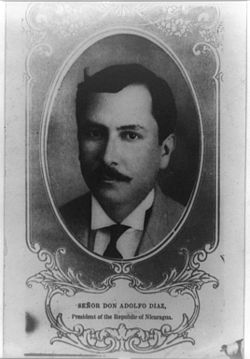

On October 10, 1909, a rebellion broke out on the eastern coast (Caribbean or Atlantic) against Zelaya's government. The revolutionary movement was led by General Juan José Estrada Morales, liberal governor of the Atlantic Coast; by the bookkeeper (accountant) of the "La Luz and Los Ángeles" mines, Adolfo Díaz Recinos; by a military representative of the conservative landowners, Emiliano Chamorro Vargas and by the conservative general, Luis Mena Vado.

The American consul Thomas Moffat appeared as the Deus ex machina of the counterrevolutionary movement. Juan Estrada himself, no longer being president of Nicaragua, confessed the facts in this way, in an interview with the New York Times:

- "The General Estrada, with rude sincerity, admits that the revolution he led against Zelaya had received the financial aid of certain American companies, established on the Atlantic Coast of Nicaragua. He said that such companies contributed to the (against) revolution of Bluefields with a million dollars, the house of Joseph W. Beers with about two hundred thousand and that of Samuel Weil with about one hundred and fifty thousand dollars."

The owners of the "La Luz and Los Angeles Mining Company" mines also collaborated, and were forced to hand them over to the Nicaraguan government, for breaching the clauses of the concession contract. By mere chance, the Secretary of State, Knox, was in charge of the legal advice of the Fletcher family, former concessionaire of the mentioned mines.

Facing the rebellion. the superiority of the army loyal to the government was felt from the beginning of the conflict.

Then the US minister in Costa Rica, Willian L. Merry; In November 1909, he addressed the president of that country, Cleto González Víquez, suggesting that he join Guatemala and El Salvador in a war against Nicaragua. The United States promised to provide everything they needed. But the US plan failed, since Costa Rica's interest was the economic and social development of the region and a war would only increase social problems.

To put down the rebellion, Zelaya was forced to pursue the rebels into Costa Rican territory. Once again, the US minister asked that Costa Rica break with Zelaya. Once again, the Costa Rican government refused to fight against Nicaragua, since the political background of the US actions was clear.

Faced with the refusal of the Costa Rican government, the United States took the option of strengthening the counterrevolutionary movement. There was no choice but to openly confront the Nicaraguan government, and there was no lack of reasons or immediate circumstances to do so.

The government of President William Howard Taft, who had been elected in the 1909 presidential election, appointed Philander C. Knox, a lawyer whose clients were the owners of Nicaraguan gold mines "La Light" and "Los Angeles Mining Company".

The newly incorporated Mosquitia was under the authority of General Juan José Estrada Morales who was a liberal and supported Zelaya. Estrada began to maintain relations with the American consul Thomas Noffat who, in turn, maintained excellent relations with General Emiliano Chamorro, this conservative. Estrada secured the support of the United States for a hypothetical uprising against Zelaya. This support was confirmed at the beginning of September 1909. The following day Consul Thomas reported the uprising against the Zelaya government by Generals Juan José Estrada and Emiliano Chamorro which, according to him, would take place on September 8, asking your government support and recognition for the future government. The information that Thomas sent to Washington stated that the new government would respect foreign interests and that surely President Zelaya was not going to offer armed resistance.

The uprising occurred on September 10, 1909, and Secretary of State Knox ordered the American warships stationed off Bluefields, the Paducah and the Dubuque, that they intervene in support of the insurgents. This episode was the first direct intervention of the United States in Nicaragua, an intervention that lasted until 1925.

On November 14, mercenaries were surprised with bombs in their power destined to fly the ships of the Nicaraguan government that sailed on the San Juan River, Two Americans and a Frenchman who is imprisoned for a year, did not run the same fate for the Americans executed two days later.

The Knox Note

In 1909 some foreign mercenaries were captured and executed by the Zelaya government, which served for the United States to consider the action as a provocation for war, and the overthrow of Zelaya through the Knox Note, sent by Philander Chase Knox, United States Secretary of State.

Americans Lee Roy Cannon and Leonardo Groce, plus Frenchman Edmundo Couture; They were subjected to a careful process. Once all the formalities were completed and their guilt fully confirmed, they were even allowed to say goodbye to their relatives one day before, thus they dictate their last words as evidence.

These two American mercenaries were active in the (US-funded) rebel army. On December 2, the Nicaraguan charge d'affaires in Washington received a note from the US government, known as the "Knox Note", in which they told him:

Americans shot were officers at the service of the revolutionary forces, and therefore had the right to be treated in accordance with the modern practices of civilized nations.../... the government of the United States is convinced that the current revolution represents the ideals and at the will of the majority of Nicaraguans better than the government of the presiente Zelaya... the United States Government cannot feel for the Government of President Zelaya that respect and confidence that should be maintained in its diplomatic relations

and attached the passport for him to leave the country.

Zelaya resigns as president on December 18, justifying his decision with these words:

...the hostility manifested by the United States Government, to which I do not want to give pretext so that I can continue to intervene in any way in the destiny of this country.

Causes of US intervention

1. The immediate conjuncture was that two Americans, Cannon and Groce, had been surprised with bombs in their possession intended to blow up Nicaraguan government ships sailing on the San Juan River. Zelaya's troops took them red-handed. They were subjected to a careful process. Once all the formalities were completed and their guilt fully confirmed, they went under arms.

The guilt of the two Americans was beyond doubt and their death was the final pretext for open US intervention in Nicaragua.

2. But it was not just that: Zelaya had refused to accept a loan offered to him by US bankers with the backing of the US government.

3. At the same time, Zelaya contracted a loan with the British bankers of the Ethelburg House that had as objective the construction of a railway that linked the Atlantic to the Pacific of the country, and for, as Zelaya himself says, " Free national commerce from being a tributary of the Panama railroad... and also carry out the consolidation of our foreign debt".

But there was something else: the United States had the purpose of obtaining the canal concession for Nicaragua and they could not find the facilities with Zelaya, since he demanded that the sovereignty of Nicaragua and an amount of money corresponding to the importance of the construction site.

The attitude of the Nicaraguan government did not fit into the political and financial plans of the American bourgeoisie. Zelaya was a hindrance to dollar diplomacy and had to be removed.

The diplomacy of the dollar consisted of the granting of loans to certain countries under more or less onerous conditions, with official guarantees of the United States government, which assured the bankers a reasonable guarantee, as a guarantee of the investment the bankers took under their control: the railways, the telegraphs and the customs of the countries favored by the emprestito; if the state resisted to renegade its sovereignty,

Countries reluctant to accept loans from US bankers were induced to accept them by coercing their will through a variety of means, which were all the more effective the poorer and weaker the country that the States officially wanted to protect. United with their pecuniary support.

In the case of Nicaragua, in addition to economic and financial reasons, dollar diplomacy also responded to geopolitical reasons linked to the possibility of building an Interoceanic canal.

Zelaya fought against the tremendous thrust of the Americans who supported and protected supporters of the counterrevolution and US intervention.

Second Conservative Republic (1911-1929)

The National Assembly (Congress) appointed the liberal José Madriz Rodríguez as president who was not pleased with the United States (he had already expressed it in Note Knox when he referred to it "a presidential candidate intimately linked to the old regime").

Madriz sent troops to Bluefields against the insurgents and took the El Bluff fort that closed the port of the city, leaving it under his control. The United States Marine Corps landed in the city in May 1910, so it remained on the rebel side as government troops could not take it. The Bluefields customs office remained under the control of Madriz, but the United States Navy established another customs office under the authority of Estrada, and the US government stated, over the protest of the Nicaraguan government, that each fraction collect duties only in the territory under its control.

José Madriz resigns from the presidency on August 19 and shortly after, Generals Estrada Morales and General Chamorro Vargas enter Managua. The new National Assembly appoints José Dolores Estrada Morales as President, who ceded power to his brother, the insurgent general Juan José, being named vice president Adolfo Díaz, who had been an employee of the La Luz and Los Ángeles mines and was known by the secretary of Knox State.

On January 1, 1911, the United States recognized the new government of Nicaragua. Estrada Morales signed the Dawson Pacts with the United States (by Thomas C. Dawson, envoy of the US government), and called elections to form a new Constituent Assembly, which drew up a new Constitution. Among other changes, Catholicism became the official state religion, at the request of the conservative Emiliano Chamorro. Shortly after, Estrada Morales was forced to resign and Díaz was named President of Nicaragua.

The influence of the United States increased during the government of President Adolfo Díaz, who placed control of the main state-owned companies in US hands.

Libero-conservative revolution of 1912

On July 29, 1912, a new uprising broke out at the request of General Luis Mena Vado, a conservative, and later supported by Doctor and General Benjamín Zeledón, a liberal. This rebellion is known as the libero-conservative Revolution of 1912, which is misnamed Mena's War.

The rebels take several cities including Granada, a conservative stronghold, León and Masaya, liberal strongholds.

The Díaz government requests military aid from the United States and the United States government responds with the landing in Puerto Corinto of Marines who besiege and attack Granada taken by the forces of General Mena, who surrenders it without offering resistance, taking Mena prisoner He is exiled to Panama.

Supreme command rests with General Zeledón, who fortifies himself in the "Coyotepe" and "La Barranca", near the besieged Masaya, which he maintained until the decisive battle on October 4, when he was killed by conservative soldiers of La Constabularia, loyal to Díaz and known as caitudos.

To put an end to this short but bloody Nicaraguan civil war, the United States mobilized 2,500 men and 8 warships to Nicaragua. After the battle of Coyotepe, he only left 400 soldiers as part of the so-called American Legation.

As a consequence of this last intervention, the country would remain occupied by the United States until 1933 (from 1912 to August 3, 1925, and then from 1926 to 1933, with a brief interval of nine months in between).

In 1914 the Bryan-Chamorro Treaty was signed, through which all the rights for the construction of a future interoceanic canal were ceded to the United States, in exchange for three million dollars. Despite the fact that the Panama Canal had already been built in 1903, the area continued to be of strategic interest. Also by this treaty, the United States was given the right to establish a military base in the Gulf of Fonseca for a period of 99 years, and the Corn Islands were leased to it for the same period of time.

Constitutionalist war

Between 1917 and 1926 Nicaragua was dominated by the conservative party. The US marines, present in the country since 1912, withdrew in August 1925. The following year, however, there was a new liberal uprising, which produced a new civil war, the so-called Constitutionalist War.

The negotiations in the so-called Blackthorn Pact in Tipitapa between the government and the rebels, promoted by the United States, gave rise to a coalition government. However, since the government was unable to control the new sources of insurrection, the marines landed again in December 1926.

In the 1920 elections, Diego Manuel Chamorro was elected President and took office the following year. Chamorro died in 1923 and was succeeded by his vice president, Bartolomé Martínez, who set himself the goal of settling the debt that the country had with some American bankers. The objective was fulfilled the following year after having risen to the presidency and now free of the economic burden, elections were called for the month of October of that same year for which a single candidacy was made between conservatives and liberals. As president was Carlos Solórzano Gutiérrez, a conservative and for vice president the liberal Juan Bautista Sacasa.

Solórzano was sworn in as president in January 1925 and by August of that year all the US soldiers had left Nicaraguan territory. In October Emiliano Chamorro rose up in arms against the government and took the Tiscapa Hill. To appease the rebellion and on the advice of the US government, Solórzano appointed Chamorro head of the public force.

The tensions between the two end with the resignation of the president who passes the presidential powers to Senator Sebastián Uriza and he passes them on to Chamorro and finally ends up in the hands of Adolfo Díaz leaving Sacasa out.

In May 1926, Sacasa's supporter, General José María Moncada, took up arms asking for power for Sacasa. The insurrection of the liberals was supported by the Mexican government of Elías Calles.

The response from the conservative-supporting United States was to send in the Marines again. On Christmas Eve 1926, US troops landed in Puerto Cabezas. On Three Kings Day 1927, there were more than 5,000 US soldiers and sailors on Nicaraguan soil, supported by 16 warships. Adolfo Díaz justified the intervention with these words

"Nicaragua is a weak and poor country that cannot resist the invaders and agents of the Mexican Bolshevik."

In February 1927 the most destructive fratricidal combats occurred when the 500 men of the so-called Liberal Constitutionalist Army of the West faced off against the conservative troops loyal to Díaz supported by the marines in the battle of Chinandega.

Sandino

Augusto C. Sandino, then 31 years old, had just returned from spending 5 years working as a mechanic in Mexico, Honduras and Guatemala. When he found out about the liberal insurrection of Sacasa he formed an armed force that joined the liberal forces. After some defeats he went into the mountains of Nueva Segovia. When he found out that the Mexicans had sent arms, he headed down the Coco River to Puerto Cabezas to ask Sacasa to arm him.

In Puerto Cabezas, the intervention of US troops had succeeded in disarming the Liberals. The Americans threw the weapons sent by the Mexicans into the sea. When Sandino arrived, he found that there were no weapons and that they were at the bottom of the bay. Using some supporters, including a significant number of women from the city, he managed to recover 30 rifles and 6,000 cartridges. After speaking with Moncada in the city of Prinzapolka he went back to his base in Las Segovias.

Sandino's forces were growing. During the first half of 1927 he fought the conservatives, whom he defeated and took various positions, according to Moncada's instructions. The last square taken was the hill of "El Común" in Boaquillo where he remained until the Pacto del Espino Negro in Tipitapa on May 4, which according to Sandino's words was where

Moncada hanged the Nicaraguan Liberal Party.

For this pact, in which US Colonel Henry L. Stimson (special envoy of President Calvin Coolidge and omnipotentiary delegate of Nicaraguan President Adolfo Díaz) participated, Eberhard (US Minister in Nicaragua), Rear Admiral Julian Latimer, three delegates from Sacasa and General Moncada. They agreed that Díaz would remain president until the 1928 elections and that the US would requisition all weapons from both sides while supervising the electoral process.

Sandino refused to accept the agreement. Against Moncada's instructions, Sandino issued a statement in which he asked the people of Nicaragua to rise up against foreigners. In attempts to convince Sandino to accept the pact, Moncada even sent his father, a personal friend of his, to convince him; and the commander of the US forces in Ocotal (Nueva Segovia) sent him a letter asking him to lay down his arms and turn them in under the threat of outlawing and persecuting him. Sandino replied:

I got her communication yesterday and I'm understanding about her. I won't give up and I'll wait here. I want free homeland or die. I am not afraid of them; I count on the burning of the patriotism of those who accompany me. A.C. Sandino.

Not a day passed when on July 15, 1927 Sandino's troops took the city of Ocotal giving rise to the Battle of Ocotal. The city was defended by the US Marines and the Nicaraguan National Guards who entrenched themselves in the barracks. Sandino refused to set the city on fire, as some of his men had requested to force the Marines and National Guardsmen to surrender or annihilate them. Later, the insurgents left Ocotal, once the US aviation bombarded and razed the city.

The persecution of Sandino was carried out with the destruction of peasant villages and the killing of many peasants on suspicion of the support they might be giving him. The Sandinista troops suffered several defeats such as that of San Fernando, in July, or that of Las Flores shortly after.

With the arrival of autumn, a victorious campaign began, taking Telpaneca and emerging victorious in Las Cruces, Trincheras, Varillal and Plan Grande. He established his headquarters in El Chipote, one of the heights of Las Segovias.

He carried out various incursions such as attacking and destroying the La Luz mine, owned by former US Secretary of State Knox, or the battle of Bramadero. Sandino's actions were giving him fame throughout the country and in the other countries of Latin America. That fame caused many men to arrive willing to join his ranks. In mid-1928 Henri Barbusse called him the General of Free Men.

At the end of November 1928, Rear Admiral D.F. Sallers invited him to abandon the fight and thus obtain the consequent benefits Sandino's response was;

The sovereignty of a people is not discussed, but is defended with arms in the hand... armed resistance will bring the benefits to which you allude, exactly as any foreign interference in our affairs brings the loss of peace and provokes the wrath of the people.

Second Liberal Republic (1929-1936)

The presidential elections of November 1928 were won by the liberal Moncada. Moncada took possession on January 1, 1929. Moncada continued to collaborate with the Americans in the persecution of Sandino. By the month of March of that year, 70 towns had already been razed, the bombardments were continuous and even affected the neighboring Honduran city of Las Limas.

Sandino made a trip to Mexico to try to get support. Upon his return, on May 7, 1930, he found that the Americans had formed a national guard to fight the guerrillas. That guard had to be paid for with Nicaraguan funds. Due to the weak economy of the country, public schools were closed to meet these expenses.

By July 1931, the Sandinistas had 8 guerrilla columns spread throughout Nicaraguan territory. A year later it was Sandino himself who published the reports on the activities of his forces. Before the elections of 1932 Sandino made a campaign of abstention. For those elections the candidate of the liberal party was Sacasa (although the preference of the US embassy would have been Anastasio Somoza but he was too young and inexperienced).

Sacasa won the presidency and Sandino responded by appointing General Juan Gregorio Colindres provisional president of the Free Territory of Las Segovias and seized the town of San Francisco Carnicero, near Managua, to seize the official seals.

Sandino's victories were discrediting the United States and the cost of the war became unbearable in an economy that was in full crisis, in such a way that the population began to pressure their government to abandon Nicaragua. Once Sacasa was elected, US troops began to leave Nicaragua and when he was sworn in as president, on January 1, 1933, there were no US soldiers left on Nicaraguan soil.

With no foreign soldiers in Nicaragua and other pressures, Sandino reached a peace agreement with Sacasa. The National Guard under the command of Anastasio Somoza (created by the United States and commanded by a man he trusted) continued with the repression against Sandino's men even when he asked the president to stop the actions of the Guard.

The assassination of Sandino

On February 21, 1934 Sandino in the company of his father, Gregorio Sandino, the writer Sofonías Salvatierra and generals Estrada and Umanzor attended a dinner at the presidential house invited by Sacasa. At the exit of said event, the car in which they were traveling was stopped just outside the gardens of the presidential house. The guard corporal who stopped them was actually a major in disguise, named Delgadillo, who led them to the Hormiguero prison. The detainees asked that they call Somoza, but they replied that they could not locate him. On the other hand, Sacasa's daughter informed her father of the arrest, since she had seen her, and Sacasa contacted the United States embassy to try to stop the murder.

Sandino, Estrada and Umanzor were taken to the hill called La Calavera in the Larreynaga camp and there, at Delgadillo's signal, the battalion guarding the prisoners opened fire, killing the three generals. That happened at 11 p.m. Upon hearing the shots, according to Salvatierra's testimony, Gregorio Sandino said,

They are already killing them; it will always be true that the one who gets into a redemptive dies crucified.

A year later, Anastasio Somoza, who went so far as to say that he received the orders for Sandino's assassination from US Ambassador Arthur Bliss Lane, would seize power in the country.

Somocism (1936-1979)

Government of Anastasio Somoza García

Before leaving Nicaragua, the marines handed over command of the 4,000 soldiers enlisted in the National Guard to Anastasio Somoza García, a nephew-in-law of President Sacasa who had earned the trust of the ambassador and top American officials. He would soon turn this military force into a formidable instrument of personal power. On February 21, 1934, the new chief director of the National Guard would have started his offensive, having Sandino assassinated when he was leaving a dinner at the government house, to which he had been invited by the president himself. The following day the execution of more than three hundred Sandinista peasants accused of conspiracy, including women and children, who were in an agricultural cooperative in Wiwilí, east of Las Segovias, was unleashed. Then the armed forces were reorganized, purging Somoza's opponents and placing his associates in key positions throughout the country. Finally, he concentrated on strengthening his influence in Congress and the Liberal Party, using the army budget, which represented more than half of the state's tax revenues. Once this was achieved, Somoza began to deploy an open campaign to reach the presidency, despite the fact that the current Constitution prohibited him from holding that position, given his relationship with Sacasa and his status as an active military officer (a situation that would be resolved a month before the elections)., resigning the position of commander). In December 1936 Somoza won the presidential elections and became president of Nicaragua as of January 1 of the following year. His family would remain in power until 1979. Anastasio Somoza was president from 1937 to 1947, and from 1950 to 1956 (in the interval, he did not relinquish power, but continued to hold it through straw men [citation needed ] ). The first opposition to the Somoza regime came from the normally conservative middle and upper strata of society, who watched with disgust as the new ruler placed the country in the hands of his family and friends. Because of the limitations on freedom of expression, efforts to resist Somoza had no results. Many opponents left the country, going into exile in the United States. One notable exception was Pedro Chamorro, editor of the country's most popular daily La Prensa, whose international reputation and continued rejection of violence made him untouchable by the regime.

The liberal opposition, accused of communist inspiration, was soon eclipsed by the openly Marxist. On September 21, 1956, a young liberal poet, Rigoberto López Pérez, managed to infiltrate a party where Somoza García was present, shooting him in the chest and ending his life (Somoza would die of his wound shortly after after).

The Sandinista National Liberation Front

In 1961, the young politicians Carlos Fonseca Amador, Tomás Borge Martínez and Silvio Mayorga, inspired by the ideas of Augusto Sandino, founded the Sandinista National Liberation Front and began the insurrectionary struggle against the dictatorship of the Somoza family.

The different Somoza governments had the backing of the United States government. For its part, the FSLN, like most of the left-thinking guerrillas in Latin America in those years, had the ideological and also arms support (and military training) of Fidel Castro's Cuba. Towards the last years of the Somoza regime (1977-1979), the FSLN had the strong support of foreign governments such as Cuba, the Venezuela of Carlos Andrés Pérez, the Panama of Torrijos, and even Costa Rica (receiving Nicaraguan exiles, and lending their territory for the FSLN guerrilla troops).

The FSLN waged both urban and rural guerrilla warfare with the intent of overthrowing the Nicaraguan government from the start of its guerrilla operations in the early 1969s. These operations are known as the Jornadas de Pancasán and the guerillas of Raití and Bocay, in which some members of the Organization fell, such as Filemón Rivera, Oscar Danilo Rosales, Rigoberto Cruz, better known as Pablo Úbeda, and many more; The failure of these first guerrilla attempts was due to the lack of knowledge of the area of operations and the disinterest of the populations where they operated, since they were very uninhabited places. After the Pancasán experience, there was a period known as the Silent Accumulation of Forces, although even during these years there were clashes with the National Guard. Given the circumstances, the FSLN is divided into three tendencies, each of them with a different vision of carrying out the overthrow of the Somoza dictatorship.

The Prolonged People's War Tendency, advocated the struggle in the mountains based on the experience of the Cuban revolution and especially Ernesto Che Guevara, the Proletarian Tendency, affirmed that the overthrow would take place when the proletariat, that is, the workers and peasants, unite to overthrow the tyranny and finally the Insurrectional or Tercerist Tendency that called to arm the people and ultimately resulted in the way in which Anastasio Somoza Debayle would fall. Precisely seeking the unity of the three trends, Carlos Fonseca lost his life on November 8, 1976 in Boca de Piedra, Zinica. Although to reduce the repression unleashed as a result of some incidents in the mountains, the operation known as Victorious December takes place when a group of guerrillas under the command of Eduardo Contreras takes over the house of a Somocista minister on December 27, 1974, the date from from which the world learned of the existence of the FSLN.

In 1978, he achieved a masterful blow against the dictatorship, when an operation was carried out, called "Operation Chanchera", carried out by a guerrilla commando, which led to the seizure of the National Palace building, seat of the Congress of the Republic, and a considerable number of its members, highlighting the logistical weaknesses of the National Guard.

The guerrilla offensive launched from the north, with the support of the peasants, the working classes and industrialists tired of the Somocista policy and supported by political action and international pressure managed to enter triumphantly in the capital, Managua, while the dictator Anastasio Somoza Debayle and his family leave the country. Arriving victorious at the Revolution Square on July 19, 1979. Roberto Carlos Alfaro announces the arrival of the Sandinistas and shouts the famous saying until victory always.

Sandinismo (1979-1990)

The entry into Managua of the troops of the Sandinista National Liberation Front (FSLN) puts an end to the dictatorial power of the Somozas, who had remained in power for 43 years. On July 19, 1979, a radical change began in Nicaragua, a change that would have continental consequences and would lead to the intervention of foreign powers such as the Soviet Union and, again, the United States. After the intervention of the US and the Soviet bloc, a process of political and social instability will begin that will lead to a Civil War promoted by the two powers that were driving the thread of the Cold War context, both during the period of the presidency by Ronald Reagan and continued by Bush senior. The peace agreements were not signed until the late 1980s. At the same time, the so-called Sandinista Revolution began, which would continue until the early 1990s.