New imperialism

Modern imperialism or neoimperialism was a policy and ideology of colonial expansion and imperialism adopted by European powers and later by the United States and Japan from the late 19th century to early 20th century, roughly from the Franco-Prussian War (1870) to the beginning of World War I (1914). The adjective "new" is to contrast it with the first wave of European colonization from the 15th to the 19th centuries and with imperialism in general. It is characterized by an unprecedented persecution of what has been called "empire for empire's sake", an aggressive competition for the acquisition of overseas territories accompanied by the emergence in the colonizing countries of doctrines of racial superiority that denied the ability to subjugated peoples to govern themselves.

As in 1880 most of Africa was still unoccupied by Western powers, that continent became the main objective of the "new" imperialist expansion, giving rise to the so-called "division of Africa." Such expansion also took place in other areas, notably in Southeast Asia and the maritime regions of East Asia, Japan joined the European powers in territorial distribution.

During the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s, a wave of independence uprisings put an end to the surviving European colonial empires.

Beginnings

The American Revolution (1775–83) and the collapse of the Spanish Empire in America around 1820 ended the first era of European Imperialism, particularly in Britain this revolution showed the shortcomings of mercantilism, the doctrine of economic competition by wealth that had sustained early imperial expansion. In 1846, with the repeal of the 'Corn Laws', Great Britain began to adopt the concept of free trade.

The decline of British hegemony after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71), in which a coalition of German states led by Prussia defeated France, was caused by changes in the European and world economy and continental balance. of power after the breakdown of the European Concert established by the Congress of Vienna. The establishment of nation-states in Germany and Italy resolved territorial disputes in the European heartland. The years from 1871 to 1914 were marked by an extremely unstable peace. France determined to recover Alsace-Lorraine annexed by Germany after the Franco-Prussian War and Germany mounting imperialist ambitions, would keep these two nations constantly prepared for conflict.

This competition intensified with the Great Depression of 1873, a prolonged period of price deflation marked by a serious economic crisis, which pressured governments to promote national industry, leading to the general abandonment of the ideas of free trade. trade between the powers of Europe (In Germany since 1879 and in France since 1881).

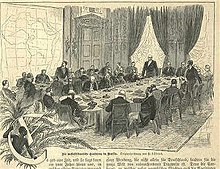

Berlin Conference

The Berlin conference held between 1884 and 1885, was convened by Portugal and Leopold II of Belgium for their interests in the Congo estuary, and organized by the German Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, in order to resolve the disputes. problems posed by colonial expansion in Africa and resolving its distribution by the great European powers. The conference was held due to the jealousy and distrust with which these powers moved in their colonial expansion in Africa and coincided with the appearance of the German Empire as an imperial power.

The main dominant powers at the conference were France, Germany, Great Britain and Portugal. Africa was reassigned without regard to the cultural and linguistic boundaries that had already been established. At the end of the conference, Africa was divided into 50 different colonies. The assistants established control of each of these newly divided colonies. They also planned, without compromising, to end the slave trade in Africa. No African country was represented.

An attempt was made to destroy competition between powers through the concept of "uti possidetis iure" or "effective occupation" as a criterion for international recognition of a territorial claim, especially in Africa. The imposition of this type of direct rule made it necessary to use armed forces against states and indigenous peoples.

Uprisings against imperial rule were ruthlessly repressed, especially in the so-called Herero genocide in German South West Africa 1904-1907 and the Maji Maji rebellion in German East Africa 1905-1907.

One of the objectives of the conference was to reach agreements on trade, navigation and the boundaries of Central Africa.

Great Britain during the era of the New Imperialism.

In Britain, the era of the New Imperialism marked a time of significant economic change. Because the country was the first to industrialize, Britain was technologically ahead of many other countries for most of the 19th century. However, at the end of the 19th century, other countries such as Germany, the United States, Russia and Italy soon caught up. with it in terms of technological and economic power. After several decades of monopoly, the country struggled to maintain a dominant economic position, as other powers became more involved in international markets. In 1870, Britain owned 31.8% of the world's manufacturing capacity, while the United States had 23.3% and Germany 13.2%. By 1910, Britain's industrial capacity had fallen to 14%..7% worldwide, while in the United States it had increased to 35.3% and in Germany to 15.9%. As countries like Germany and the United States grew economically, they began to become involved with imperialism, resulting in the British fighting to maintain its trade volume and overseas investment.

Britain faced tense international relations with the three expansionist powers (Japan, Germany and Italy) during the early part of the 20th century. Before 1939, these three powers never directly threatened England itself, but the indirect dangers were clear. By the 1930s, England was concerned that Japan was endangering its possessions in the Far East, as well as the territories of India, Australia and New Zealand. Italy was showing interest in East Africa, threatening British Egypt, and German expansionism on the European continent threatened the security of England. With its stability and exploitation threatened, Britain decided to adopt a policy of concession rather than resistance, a policy that became known as appeasement.

In Britain, there was almost no anti-imperialist opposition. Beyond some isolated Marxist group, the majority thought that imperialism must exist, and it was better for Britain to be its driving force. British imperialism was also thought to be a force for good in the world. In 1940 the Fabian Society established the Fabian Office of Colonial Research, which argued that Africa could develop both economically and socially, but for this development to happen, it must remain in the British Empire. Rudyard Kipling's 1891 poem, "The English Flag," contains the stanza:

| Winds of the World, give answer! They are whimpering to and fro... 'And what should they know of England who only England know?--' 'The poor little street-bred people that vapour and fume and brag,' 'They are lifting their heads in the stillness to yelp at the English Flag!' | Winds of the world, give the answer! They're groaning here and there.

And who should know of England that only England know? The poor little people, raised in the streets with steam and smoke and boast, They lift their heads from the stillness to plow the English flag! |

|---|

These lines show Kipling's belief that the British who actively participated in imperialism knew more about British national identity than those whose lives were spent solely in the imperial metropolises. In many ways, this new form of imperialism was part of British identity until the end of the era of the new imperialism, with the First World War.

Social implications

Neo-Imperialism gave rise to new social views of colonialism. Rudyard Kipling in his poem 'The White Man's Burden', urged the United States to 'Take the burden' of bringing European civilization to the other peoples of the world, regardless of whether these "other peoples" whether they want this civilization or not. This part of "the white man's burden" It is an example of Britain's attitude towards the colonization of other countries:

| Take up the White Man's burden—

In patience to abide, To veil the threat of terror And check the show of pride; By open speech and simple, An hundred times made To seek another's profit, And work another's gain. | Take the burden of the white man

Showing patience, Hiding the threat of terror And without pride to show; With frank and simple speech, A hundred times repeated To seek the benefit of another, And break the gain of others. |

|---|

As Social Darwinism became popular throughout Western Europe and the United States, the "civilizing mission" French and Portuguese (French: mission civilisatrice; Portuguese: Missão civilizadora) attracted many European statesmen, both inside and outside France. Despite the apparent benevolence of the notion of the 'white man's burden', the unintended consequences of imperialism were far greater than its potential benefits. Governments became increasingly paternalistic at home and neglected the individual freedoms of their citizens. Military spending expanded, leading to "imperial overreach", and clients of ruling elites abroad were created who were cruel and corrupt, consolidating their power through imperial revenues and hindering social change and economic development contrary to their ambitions. Also "national construction" It often created cultural feelings of racism and xenophobia.

Europe's leading elites also found advantages in overseas expansion. Large financial and industrial monopolies used imperial support to protect their overseas investments against competition and local political tensions abroad; The bureaucrats asked for government offices, the military wanted their promotion, and the traditional gentry sought to increase the benefits of their investments, official titles, and high positions. All of these special interests made the empire perpetuate throughout history.

With the rise of unionism, socialism, and other protest movements during the era of mass society in Europe and later North America, elites sought to use imperial jingoism to co-opt support from part of the industrial working class. New media promoted jingoism in the Spanish-American War (1898), the Second Boer War (1899-1902), and the Boxer Rebellion (1900). The left-wing German historian Hans-Ulrich Wehler defined social imperialism as "the outward diversion of internal tensions and forces of change in order to preserve the social and political Status Quo,", and as " 34;defensive ideology" to counteract "the disturbing effects of industrialization on the social and economic structure of Germany". In Wehler's view, social imperialism was a mechanism used by the German government to distract public attention from internal problems and preserve the existing social and political order. Dominant elites used social imperialism as an excuse to hold a fractured society together and thus maintain popular support for the social status quo. According to Wehler, German colonial policy in the 1880s was the first example of social imperialism in action. It was followed by the Tirpitz Plan in 1897, for the expansion of the navy. According to this view, groups such as the Colonial Society and the Naval League are seen as instruments of the government to mobilize popular support. The demands for annexation of most of Europe and Africa in World War I are seen by Wehler as the pinnacle of social imperialism.

The notion of dominion over foreign lands was widely accepted among metropolitan populations, even among those who associated imperial colonization with oppression and exploitation. For example, in 1904 the Congress of the Socialist International came to the conclusion that colonial peoples must allow themselves to be taken over by future European socialist governments and be led by them towards eventual independence. [citation needed]

India

In 1599, a group of British merchants arrived in India and with the support of the crown they formed the British East India Company. Between 1610 and 1611 they installed trading establishments called factories in the territory of India, where they came to govern large areas with their own armies, with which they exercised military power and assumed administrative functions, ranging from the territories of Bengal in 1757 and to Punjab in 1849. This was helped by a power vacuum produced by the death of Emperor Aurangzeb in 1707 with the consequent collapse of the Mughal Empire in India and with the progressive increase of British forces in India due to the colonial conflicts with France. The French, for their part, ventured into India in 1664, founding the Compagnie des Indes Orientales and an enclave in Pondicherry on the Coromandel Coast. By 1818, the British controlled most of the Indian subcontinent and began introducing their ideas and customs to the residents, including succession laws that allowed the British to take over a state without any successor and seize its lands and armies, charging new taxes, and exercising monopoly control of the industry.

The British company began to use the so-called sepoys, which were soldiers trained by Europeans, but led by Indians, to protect their trade and to resolve power disputes between local chiefs. In 1857 a mutiny arose, which became known as the Sepoy Rebellion, or the Indian Mutiny. The revolt was suppressed by the British, but resulted in the dissolution of the British East India Company and India came under the direct control of the British crown then Queen Victoria. Many principalities remained independent. The resulting so-called British Raj (British crown law in India) gained control over India and began to change the country's financial situation in its favor. Previously, Europe had to pay for its textiles and spices in silver bullion; Then, with political control, Britain required farmers to produce cash crops for export to Europe, while India became a market for textiles from Britain. The British collected huge revenues from land rent and taxes on salt production. Indian weavers were replaced by spinning and weaving machines and Indian food crops were replaced by cash crops such as cotton and tea.

The British connected cities by rail and telegraph to facilitate communications. The invention of the Clipper ship in the early 1800s cut the journey from Europe to India in half, from almost 6 to 3 months. By 1870 the British had already laid telegraph cables across the ocean floor connecting India and China. They also built irrigation systems to increase agricultural production. When Western education was introduced in India, Indians were greatly influenced by it, but the inequalities between the ideals of British governance and their treatment of Indians became evident. In response to this discriminatory treatment, a group of educated Indians established the Indian National Congress, demanding equal treatment and self-government.

John Robert Seeley, professor of history at Cambridge University, said: "Our acquisition of India was done blindly. Nothing great that the English ever did was accomplished so unintentionally or accidentally as the conquest of India." According to him, the political control of India was not a conquest in the usual sense, since it was not an act of a state.

The new administrative arrangement, crowned by the proclamation of Queen Victoria as Empress of India in 1876, effectively replaced the rule of a monopoly company with that of a public administration headed by graduates of Britain's leading universities. The administration retained and increased the monopolies held by the company. The Indian Salt Act of 1882 put into regulations the government's monopoly on the collection and production of salt; In 1923 a bill was passed to double the salt tax

Southeast Asia.

After taking control of much of India, the British expanded into Burma, Malaya, Singapore, North Borneo, Sarawak and Brunei, turning these colonies into other sources of trade and raw materials for British products.

Contenido relacionado

179

38

August