Nevado del Ruiz

The Nevado del Ruiz Volcano, or the Mesa de Herveo, in pre-Columbian times as Cumanday, Tabuchía and Tama, it is known by the name "del Ruiz", perhaps in honor of Alfonso Ruiz de Sahajosa, member of the council and notable person of Ibagué, it is the most northern part of the active volcanoes of the Andes volcanic belt, located on the border between the departments of Tolima and Caldas, in Colombia. It is a stratovolcano composed of many layers of lava that alternate with hardened volcanic ash and other pyroclasts. It has been active for about two million years, from the Early Pleistocene or Late Pliocene, with three major eruptive periods. The formation of the volcanic cone prepared during the course of the current eruptive period began 150 thousand years ago.

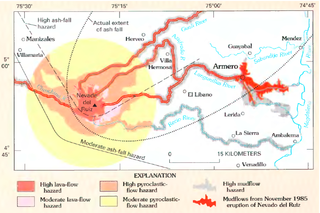

In general, its eruptions are of the Plinian type, giving rise to rapid turtles of hot gas and rock called pyroclastic flows. These massive eruptions often generate lahars (mud and debris flows), which pose a threat to human life and the environment. On November 13, 1985, a small eruption triggered a huge lahar that buried the urban capital of Armero in what became known as the Armero tragedy, in which, according to an estimate, approximately 25,000 deaths occurred, for which reason it is considered as the second most devastating volcanic eruption of the 20th century, after the eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902. Similar incidents occurred in 1595 and 1845, but were less deadly.

The volcano is part of the Los Nevados National Natural Park and includes other snow-capped peaks such as Nevados del Tolima, Santa Isabel, El Cisne and Quindío, which are covered by glaciers that have been retreating significantly since 1985 to cause of global warming. The park is a popular tourist destination and includes several shelters for tourists; the slopes of the volcano are used for winter sports, and the Laguna del Otún, for trout fishing. Likewise, in the region there are some spas with commercially operated thermal waters. Between 1868 and 1869, the German geologists Reiss and Stübel were the first to attempt to scale the Ruiz in a documented expedition, and in 1936, Cunet and Gansser were the first to do so successfully, which they repeated in 1939.

Geography and geology

The volcano is located 220 km west of Bogotá and is part of the Andes Mountains, specifically the Ruiz-Tolima volcanic massif (or Central Mountain Range), which also includes the Nevado del Tolima, Santa Isabel, del Quindío and Cerro Machín. The massif is located at the intersection of four faults, some of which are still active.

It is part of the Pacific Ring of Fire and is the northernmost of the Andean volcanic belt, which includes 75 of the 204 South American volcanoes formed during the Holocene. This belt is the result of easterly subduction of the Nazca plate below the South American plate. As in the case of other volcanoes in subduction zones, Nevado del Ruiz can give rise to explosive plinian eruptions associated with pyroclastic flows that can melt glaciers surrounding the summit, producing lahars..

Like many other Andean volcanoes, Nevado del Ruiz is a stratovolcano, that is, a high-altitude, conical volcano, composed of multiple layers of hardened lava, alternating pyroclastic rocks, and volcanic ash. Its lavas are of andesitic–dacitic; the modern volcanic cone comprises four lava domes, all of them built inside the ancestral Ruiz caldera: Alto de la Laguna, la Olleta, Alto la Piraña, and Alto de Santano. Cisne as part of the Ruiz lava domes, however in recent times it has been shown that it forms a separate small volcanic complex with the morro negro. It covers an area of more than 200 km², spanning 65 km from east to west. The extensive summit includes the Arenas crater, 1 km in diameter and 240 m deep.

The top of the volcano has slopes with inclinations of 20 to 30 degrees. At lower elevations the slopes are less pronounced, with inclinations close to 10 degrees. From there, the foothills extend almost to the banks of the Magdalena to the east, and the banks of the Cauca to the west. On the two main sides of the summit, the cliffs of the glaciers show the places where landslides have occurred. land; also, on some occasions the ice of the glaciers has melted, generating devastating lahars, including the deadliest eruption of the continent in 1985. On the southwestern side of the volcano is the La Olleta pyroclastic cone, which is not currently active, but has erupted several times in the past.

Glaciers

Nevado del Ruiz is covered by glaciers, which formed several thousand years ago and have generally been retreating since the Last Glacial Maximum. From 28,000 to 21,000 years ago, glaciers covered about 1,500 km² of the Ruiz–Tolima massif. As late as 12,000 years ago, when the ice sheets from the last ice age receded, they still covered 800 km², and during the Little Ice Age, the ice sheet covered approximately 100 km².

Since then, glaciers have receded further due to warming of the atmosphere. By 1959, the glacier area had shrunk to just 34 km²; and since the 1985 eruption, which destroyed about 10 % of the icy area of the summit, it has halved, from 17 to 21 km² just after the eruption, to about 10 km² in 2003. In 1985, glaciers reached heights as low as 4,500 meters, but now they only reach elevations between 4,800 and 4,900 meters.

The ice sheet has an average thickness of about 50 m; it is thickest in parts of the summit plateau and under the Nereid Glacier on the southwestern slope, where it reaches depths of 190 m. Glaciers on the northern slopes, and to a lesser extent those on the eastern slopes, lost most of their ice in the 1985 eruption, and therefore only go as deep as 30 m. The thick ice covering the summit plateau may be hiding a caldera; five domes around the plateau have appeared as the ice has receded.

Most of the meltwater is drained into the rivers Cauca, to the west, and Magdalena, to the east. Runoff from the Ruiz glaciers and the surrounding snow-capped peaks is responsible for supplying drinking water from 40 nearby towns, so both Colombian scientists and government officials are concerned about the supply of water to cities if the glaciers were to melt completely.

Flora and fauna

In general, Nevado del Ruiz is poorly forested mainly due to its elevation, and its tree cover decreases as altitude increases. At the lower elevations, well-developed temperate forests (20–35 m) are present; above these, but below the tree line, portions of the surface contain dwarf forest (3–8 m). Above this line, in the páramo, the vegetation is dominated by Espeletia. The vegetation of the region is made up of different families of woody plants, including Rubiaceae, Fabaceae, Melastomataceae, Lauraceae and Moraceae. Some herbaceous plants, from families such as Polypodiaceae, Araceae, Poaceae, Asteraceae, Piperaceae and Orchidaceae are also present in the region.

Among the animals that inhabit the volcano are the Andean tapir and the spectacled bear, considered threatened. Also, in the surroundings of the volcano there are species such as B. ferrugineifrons, O. Stubelii and O. percrasa. In addition, Nevado del Ruiz is the habitat of the Andean condor and 27 endemic species of Colombia, with 14 of them confined to the region around the volcano. 15 species of birds in the region are also considered threatened.

Eruptive history

Its first eruptions took place 1.8 million years ago, at the beginning of the Pleistocene, from which three primary periods of eruption have been identified: the ancestral, the ancient and the current. During the first of these, between one million and two million years ago, a complex of large stratovolcanoes was created, which then partially collapsed between one million and 800,000 years ago, forming calderas between 5 and 10 km wide. During the ancient period, which lasted from 800,000 to 200,000 years ago, a new complex of large stratovolcanoes developed, including what at that time were Ruiz, Tolima, Quindío, and Santa Isabel.. Once again, explosive calderas formed on their summits, between 200,000 and 150,000 years ago.

The present period began approximately 150,000 years ago, and saw the development of the current volcanic edifice through the emplacement of andesite- and dacite-based lava domes within the old calderas. Over the past 11,000 years, Nevado del Ruiz has gone through at least 12 eruption stages, which have included multiple landslides, pyroclastic flows, and lahars, leading to the partial destruction of the summit domes. During the last thousands of years, most of the eruptions of the volcanoes of the Ruiz–Tolima massif have been small, and the pyroclastic flows deposited have been less voluminous than those of the Pleistocene. Since the oldest eruptions of the volcano have not been recorded, volcanologists have used the technique of tephrochronology to date them.

During the volcano's recorded history, eruptions have consisted primarily of a central caldera vent, followed by an explosive eruption, and then lahars. The oldest of the identified Holocene eruptions occurred around 6660 BCE. C., and new eruptions occurred in 1245 B.C. C.±150 years (using radiocarbon dating), about 850 B.C. C., in 200 a. C.±100 years, as well as in 350 d. C. ±300 years, 675 AD. c.±50 years, in 1350, 1570, 1595, 1623, 1805, 1826, 1829, 1831, 1845, 1916, December 1984 to March 1985, September 1985 to July 1991, and possibly in 1541, 1687, 1828, 1833 and April 1994 and the last one on June 30, 2012, which was of gases and ash only. Many of these eruptions included a central vent eruption, one of vents on the sides, and an explosion phreatic. El Ruiz is considered the second most active volcano in Colombia, after Galeras, in Nariño.

Lahar from 1595

On the morning of March 12, 1595, the volcano erupted. This episode consisted of three Plinian eruptions that were heard more than 100 km from the summit, and a large amount of ash was ejected, obscuring the surrounding area. During eruptions, the volcano also ejected lapillus, a form of tephra, and volcanic bombs. In total, the eruption produced 0.16 km³ of tephra. The eruption was preceded by a major earthquake, three days earlier; and the precursor eruption caused lahars, which traveled down the valleys of the Gualí and Lagunilla rivers, obstructing the flow of water, killing fish and destroying vegetation. 636 people died from the lahar.

1595 was the last major eruption before 1985; and they were similar in many respects, including the chemical composition of the erupted material.

1845 mudflow

On the morning of February 19, 1845, a major earthquake resulted in a mudflow, which ran down the Lagunilla valley for approximately 70 km, spreading and spilling out of the riverbed and killing much of the local population. After overcoming an alluvial fan, the mudflow split into two branches: the larger joined the Lagunilla and continued to join the Magdalena, while the smaller was diverted by the hills in front of the Lagunilla canyon, to later flow to the east next to the Sabandija river and finally rejoin the main flow at the mouth of the river. It is estimated that about a thousand people died as a result of what happened.

Gunsmith Tragedy

Since early November 1984, geologists noted an increase in the level of seismic activity near Nevado del Ruiz; as well as other indications of the approaching eruption, such as increased activity of fumaroles, the sulfur deposit at the summit of the volcano, and small phreatic eruptions. Ultimately, the hot magma came into contact with the water, resulting in explosions due to the almost instantaneous evaporation of the water. The most notable of these events was the ejection of ash on September 11, 1985. The volcano's activity subsided in October 1985, with rising magma in the new volcanic edifice, prior to September 1985, being the most significant explanation. probable of events.

An Italian volcanological mission analyzed gas samples from vents along the Arenas crater floor, obtaining carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2), indicating a direct release of magma to the surface environment. According to the considerations of the mission report, published on October 22, 1985, the risk of lahars was very high. In addition, the report recommended several simple preparation techniques for local authorities.

In November 1985, volcanic activity increased once more as the magma neared the surface. The volcano began to spew increasing amounts of sulfur-rich gases, mainly sulfur dioxide; the water content of the fumaroles was reduced, and the nearby water sources were enriched with magnesium, calcium, and potassium leached from the magma. The temperatures of thermodynamic equilibrium (steady thermal energy), corresponding to the chemical composition of the discharged gases, it was from 200 °C to 600 °C. The extensive outgassing of the magma caused an increase in pressure inside the volcano, just in the space above the magma, which ultimately led to an explosive eruption.

Eruption and lahars

Nevado del Ruiz erupted at 9:09 p.m. m. on November 13, 1985, ejecting dacitic tephra more than 30 km into the atmosphere. The total mass of erupted material, including magma, was 35 million tons, only 3% of the amount ejected by St Helens in 1980. The eruption reached level 3 on the volcanic explosivity index. The mass of sulfur dioxide ejected was approximately 700,000 tons, or about 2% of the mass of solid material ejected, making the eruption was atypically rich in sulfur. The eruption produced pyroclastic flows that melted the glaciers and snow, generating four lahars that ran down the slopes of the volcano; they also destroyed a small lake that could be observed in the Arenas crater several months before the eruption. Since volcanic lakes are usually extremely salty and contain dissolved volcanic gases, the acid composition of the lake, as well as its heat, accelerated the melting of the ice; this effect was confirmed by the large amounts of sulfates and chlorides found in the lahar.

The lahars, made up of water, ice, incandescent pyrocastic material, pumice, sand, mud, and other rocks, mixed together as they moved downhill. They continued their journey at an average speed of 60 km/h, eroding the ground, dragging rocks and destroying vegetation. After descending kilometers, the lahars headed for the six rivers that drain the volcano. Once in their valleys, the lahars grew to almost four times their original size. In the Gualí River, a lahar reached a maximum width of 50 m.

One of the lahars virtually wiped out the small urban area of Armero, in Tolima, which sat above the Lagunilla valley. Only a quarter of its 28,000 inhabitants survived. The second lahar, which descended through the Chinchiná valley, killed about 1,800 people and destroyed about 400 houses in Chinchiná. In total, more than 23,000 people lost their lives. lives and another 5,000 were injured, and more than 5,000 homes were destroyed. The Armero tragedy was the second deadliest volcanic disaster of its century, being surpassed by the eruption of Mount Pelée in 1902. known history. It is also the deadliest lahar on record, and the largest natural disaster in Colombia.

The loss of so many lives was due to the fact that scientists never pinpointed when the eruption would occur, and because government authorities would not take costly preventive measures without clear warning of danger. On the other hand, as the The last eruption had occurred 140 years ago, it no longer existed in the memory of the inhabitants and for many it was difficult to accept the danger posed by the volcano, which the inhabitants knew as the sleeping lion. The maps The threat reports showing the completely flooded Armero Municipality were distributed a month before the eruption, but the Congress of the Republic criticized scientists and civil defense agencies for their alarmism. Local authorities failed to alert the population to the seriousness of the situation, with the mayor and the parish priest of Armero reassuring the population after an ash eruption on the afternoon of November 13 and the subsequent ash fallout at night. Another factor was the storm that night, which caused power outages, making communications difficult. Although civil defense officers from four nearby towns attempted to warn Armero of the approaching lahar that would arrive in an hour or less, they were unable to establish radio contact.

After the catastrophe, scientists analyzed pre-eruption data and noted that several long-period earthquakes had occurred, starting strong and slowly fading. Volcanologist Bernard Chouet reported that: "the volcano was screaming 'I am about to explode,'" but the scientists who were studying the volcano at the time of the eruption had no the experience to read these signs.

Activity in 2023

Nevado del Ruiz is a volcano that has been erupting for approximately 10 years, but all the eruptions it has made in this period have been minor and its affectation has been limited to ash fall in different places depending on the direction of the wind. However, since March 24, 2023, the seismic activity on the southern flank of the volcano began to increase significantly and on March 29, the highest number of daily earthquakes recorded since its seismic activity began to be monitored from the beginning was recorded. year 1985. For this reason, the Colombian Geological Service changed its level of activity from yellow (with an unstable behavior in which increases in seismic activity are contemplated but not a major eruption than it has done in the last decade) to orange (It is likely that, in days or weeks, it will erupt more than it has in the last decade.)

The causes of the change in the activity of the Nevado del Ruiz volcano is that it is a magmatic intrusion, that is, a process by which magma moves from a deeper source towards the surface. In this process, earthquakes are generated. The most feasible option is that the magma is moving through one of the main fault systems in Colombia: La Palestina, where the volcanic chain of the Los Nevados National Natural Park is located. La Palestina is one of the magma ascent routes for the Nevado del Ruiz volcano, so it is believed that a portion of magma is pushing from the southern part of the volcano towards the crater. The movements that are generated inside the volcano generate earthquakes, the Nevado del Ruiz volcano has registered an average of 6000 earthquakes per day in the month of April. For this reason, continuous and detailed monitoring is important, in order to timely report on changes in your activity.

Current threats and preparation

The volcano continues to pose a serious threat to nearby populations. The most likely risk is that small-volume eruptions could destabilize the glaciers and generate lahars. Despite the significant reduction in the size of the glaciers, the volume of ice on the snow-capped peaks of the area remains large. If only 10% of the ice melted, it could produce mudflows of more than 200 million cubic meters, similar to the flow that buried Armero in 1985. Since lahars can travel more than 100 km through valleys of the rivers in a matter of a few hours, estimates show that some 500,000 inhabitants of the Chinchiná, Lagunilla, Azufrado and Gualí river valleys are at risk, and 100,000 of them are considered high risk. Although small eruptions are more likely, the two-million-year eruptive history of the Ruiz–Tolima massif includes numerous eruptions of significant magnitude, so the threat of a large eruption should not be ignored. could have more widespread effects, including the possible closure of the Bogota airport due to ash fall.

As the Armero tragedy was exacerbated by a lack of early warning, reckless use of land, and the lack of preparedness of surrounding communities, the Colombian government launched an official program called the National Office for Disaster Assistance, in 1987, with the purpose of preventing similar incidents in the future. The main Colombian cities were oriented to promote prevention planning in order to mitigate the consequences of natural disasters, and evacuations have been carried out due to volcanic threats. About 2,300 inhabitants of the banks of five nearby rivers were evacuated when the volcano erupted again in 1989. When another Colombian volcano, Nevado del Huila, erupted in April 2008, thousands of people were evacuated, as volcanologists alerted to the population affirming that the eruption could be another "Nevado del Ruiz"; In the same way, the area surrounding Galeras has been constantly evacuated due to its activity.

In April 2012, the volcano increased its seismic activity, exposing the poor preparation of the surrounding populations.

At the beginning of March 2012 there was an initial pulse of volcanic ash emission associated with the volcanic tremor. According to the Colombian Geological Service[2], the emitted ash had a volume of 1,340,000 cubic meters; Until June 8, 2012, ash continued to fall irregularly, which is why the civil aviation closed the airport in the city of Manizales and restricted air traffic in some areas of the country as a preventive measure.

The Colombian Geological Service carried out an analysis of the ashes, finding the following: according to the preliminary analysis of components and granulometry of the ash samples collected from the emission of May 29, 2012, under a binocular magnifying glass, it was possible to observe that its composition is lithic crystalline, with crystals of plagioclase, amphibole, quartz, biotite, pyroxene and magnetite; the lithics are volcanic, it also presents fragments of pumice and glass. After sieving some of the collected samples, it can be observed that the grain sizes oscillate between very coarse (1 and 2 mm) and coarse (0.5–1 mm) ash in the sectors closest to the Arenas crater, while in the municipalities of Manizales, Chinchiná, Palestina and Villamaría the grain size varies between medium ash (0.25-0.5 mm) and extremely fine ash (<0.0625 mm); and in the most distant parts the grain size is less than 0.125 mm.

Contenido relacionado

Earth mantle

Geyser

Mount Gimie