Naval battle of Iquique

The naval combat of Iquique was one of the most important confrontations that occurred during the naval campaign of the War of the Pacific. It took place in the bay of Iquique on Wednesday, May 21, 1879. In it, the Peruvian monitor Huáscar, commanded by ship captain Miguel Grau Seminario, and the Chilean corvette Esmeralda, commanded by captain Arturo Prat Chacón, faced each other. The result of this action was the sinking of the Chilean corvette and the lifting of the blockade of the port of Iquique.

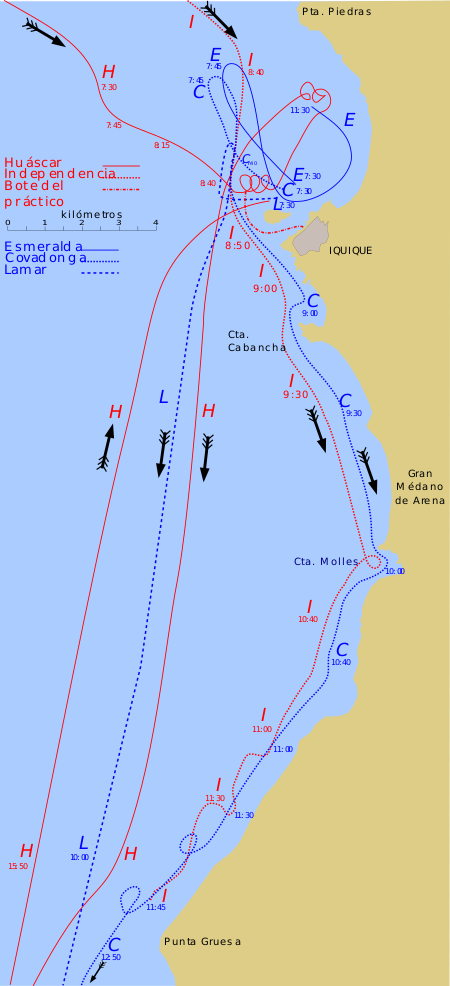

On May 16, 1879, the Chilean fleet left the Esmeralda and the Covadonga blockading the port of Iquique, as well as the Chilean transport Lamar, and sailed north to face the Peruvian fleet that he hoped to surprise in the port of Callao. However, the same day the capital ships of Peru had left heading south with the intention of defending their ports at Tarapacá. Both fleets crossed without seeing each other and the Peruvian ships found the smaller Chilean ships in Iquique on the day of the combat.

Although they began in the same place and at the same time, the confrontation of the corvette Esmeralda against the Huáscar is called the naval combat of Iquique, and that of the Independencia against the Covadonga, naval combat of Punta Gruesa (the latter is the place on the coast in front of which the outcome of the fight occurred).

After four hours of combat, the corvette was sunk by the spur of the monitor; but her crew, who fought until their ship sank, was widely admired in Chile.

Background

Before the declaration of war, the Chilean government decided as a strategy to mobilize its squadron to blockade the Peruvian port of Callao, hoping in this way to imprison the Peruvian squadron there to operate freely on the Peruvian coast or destroy it in combat if the occasion arose. Rear Admiral Juan Williams Rebolledo, Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean squadron, rejected this plan on the grounds that his ships were not in a position to launch an immediate attack on El Callao as they lacked food and fuel for the journey. Instead, Williams preferred to blockade the port of Iquique and from there to harass the Peruvian ports in the Department of Tarapacá. The Chilean squadron departs on April 3 from Antofagasta bound for Iquique to establish the blockade.

Bolivia declared a state of war against Chile on March 1, 1879. Following Peru's refusal to remain neutral, Chile declared war on both allies on April 5. On April 6, Peru declared the casus foederis, that is, the entry into force of the secret alliance with Bolivia.

On April 5, the Chilean squadron began the blockade of the port of Iquique and raided the Peruvian towns of Pabellón de Pica, Huanillos (April 15) and Mollendo (April 17), bombing trains and ships; then it bombarded Pisagua (April 18) and destroyed Mejillones Norte (April 29).

Due to pressure from the Chilean government, Williams was convinced to attack the port of Callao. For this purpose, the Chilean squadron sailed from Iquique on Friday, May 16, in an expedition to Callao with all available ships, leaving the blockade of Iquique in charge of the oldest ships of the Chilean squadron —the corvette Esmeralda under the command of Arturo Prat, subject to urgent repairs to its boilers, and the schooner Covadonga under the command of Carlos Condell—, built in 1855 and 1859, respectively. The Lamar transport also remained. Due to his greater seniority, Prat was left as head of the blockade.

To defend the Peruvian localities from the Chilean attack, Peru's plan was to finish the repairs of the ships of its squadron in Callao and transfer troops and supplies to Arica, Iquique and other ports in the department of Tarapacá and send ships to bring from Panama arms and ammunition acquired in the United States. The Peruvian commanders García, Grau and Moore, among others, disagreed with this plan since the Independencia was recently repaired and its crew had not done naval exercises while the Huáscar did not have projectiles capable of penetrating the armor of the Chilean ships Cochrane and Blanco Encalada. Despite this opposition, the Peruvian squadron set sail on May 16 from the port of Callao towards Arica carrying President Mariano Ignacio Prado aboard the flagship Oroya.

Both squadrons passed each other on the high seas without sighting each other. In Mollendo President Prado learned, by means of the steamer Ilo of the Pacific Steam Navigation Company, that the bulk of the Chilean squadron had withdrawn. In Arica he learned that they had left the ships Covadonga, Esmeralda and a transport in charge of the blockade of Iquique, so Prado decided that the Huáscar i> and the Independencia will sail to Iquique to break the siege, capturing or destroying the Chilean ships.

Fighting forces and ships

The opposing ships were extremely unequal, Peruvian steel ships against Chilean wooden ships. The Esmeralda had almost no boilers, which prevented defensive movements. Furthermore, from the coast she was threatened by coastal artillery.

Emerald Corvette

The Esmeralda was a wooden corvette with a crew of 201 sailors, with a displacement of 850 tons built in 1855. Its armament consisted of 12 40-lb (18.1 kilograms) cannons (fired bullet weight). Her propulsion system was mixed, steam engine and sail. At the time of entering combat, their machines were in a poor state of maintenance and were only capable of propelling the ship at a speed of 4 ns (7.4 kilometers per hour), which was reduced to 2 kt (knots) when their engines exploded. boilers.

Huascar Monitor

The Huáscar, an armored monitor-type ship with a crew of 197 sailors, displacement of 1,745 tons was built in 1865. It had a 4.5-inch (11.4-centimeter) hull. thick and its main armament consisted, in May 1879, of 2 Armstrong 300 lb (136.1 kilograms) charge cannons located in an armored rotating turret, in addition to 2 40-pound cannons (or pdr), one of 12 pounder and a 0.44-inch Gatling gun. Her propulsion system was also mixed, a steam engine and sail being capable of reaching a maximum speed, on the day of the fight, of 10.5 knots.

Land forces in Iquique

At the beginning of the actions, General Juan Buendia ordered four 9 lb (4.1 kilograms) Blakely mountain cannons to be placed on the Iquique beach, as well as soldiers who were to fire at the Chilean corvette with their rifles.

Pre-combat moves

On the morning of Wednesday, May 21, the blockade of Iquique was maintained by the corvette Esmeralda and the schooner Covadonga, both anchored 2.7 km north of the port lighthouse. For its part, the transport Lamar was anchored closer to the coast. At half past six in the morning one of the lookouts of the Covadonga, which was on duty, sighted columns of smoke approaching from the north. When the distance was reduced, it was identified that said smoke columns corresponded to the Peruvian armored vehicles Huáscar and Independencia. The commander of the Covadonga ordered the commander of the Esmeralda to warn the enemy of the presence with a cannon shot. Hearing the signal, he arranged to raise the anchor, make the crew eat and play the ready for combat. He also ordered the Covadonga to speak to confer and that the correspondence for the Chilean squadron be thrown into the sea, in a sack.

The Peruvian ships, upon sighting the Chilean ships, raised the combat flag. The Huáscar was closer to the port. Commander Grau harangued his crew:

"Tripulants of the Huáscar: We are in the sight of Iquique. There are not only our afflicted compatriots of Tarapacá. There is the enemy of the homeland still unpunished. It's time to punish him. I hope you will be able to harvest new laurels and new glories worthy of shining next to Junín, Ayacucho, Abtao and May 2. Long live Peru!"Miguel Grau Seminar Over the deck Huáscar on 21 May 1879

For his part, Prat ordered them to go out and reconnoiter the approaching ships. His ship sailed west and confirming that they were enemies, he returned and ordered Condell to follow him. Hoisting signals he gave orders: first "Did the people have lunch?", then "follow my waters"; and finally "venir al habla" and then harangued his crew. The version of the harangue that has gone down in history is a summarized stylization of the original, whose most faithful text, due to its temporal and spatial proximity to the events, is perhaps the one reported by the surviving midshipman of the Esmeralda Vicente Zégers in a letter written to his father just a week after the fight. In it, Prat's message to his men is described in the following words:

Boys: the contest is uneven, but spirit and courage. So far, no Chilean ship has ever leased its flag; I hope that this is not the occasion to do so. For my part, I assure you that as long as I live such a thing will not happen and after I fail, my officers remain, who will be able to fulfill their duty... Long live Chile!Arturo Prat Chacón Over the deck of the Emerald on 21 May 1879

When the harangue was over, the Covadonga spoke and Prat ordered Condell: "let the people have lunch!, keep funds low!, reinforce the charges!, each one to do their duty!". Condell simply replied: "all right!". When the above was finished, an explosion was heard and a column of water and foam rose near both ships, the Huáscar had fired its first shot.

On land, the port population woke up with the first cannon shot from the Covadonga and went to the beach to receive the Peruvian ships that came to free them from the blockade of Iquique.

Combat

First phase

The Chilean transport Lamar raised the United States flag and left the bay heading south. For 30 minutes, the Huáscar faced the two Chilean ships alone, until the arrival of the Independencia, who concentrated their shots on the Huáscar without major consequences.

The initial movements of the Esmeralda caused two of her boilers to explode, which reduced her gait from 6 kn to 2 kn, leaving the ship practically immobile. In response to this, Prat located his ship in front of the town, at a distance of 200 meters from the beach. In this situation, the Peruvian cannon fire could affect the town, which would force them to shoot from elevation.

After an hour of combat, all four ships had no significant damage. At about 11:30 a.m., the Covadonga, under the command of Condell, headed south, sailing close to the coast.

Grau ordered the commander of the Independencia to pursue the Covadonga. At that moment, the combat was divided into two confrontations, one between the Huáscar and Esmeralda and the other between Independencia and Covadonga.

Second phase

When the Huáscar was about 600 meters from the Esmeralda, a boat approached him, containing the port and lieutenant captain, Salomé Porras, along with the pilot Guillermo Checlay and the journalist Modesto Molina, who informed Grau that the Esmeralda was protected by a line of fixed torpedoes. Given this information, Grau decided to maintain a distance of 500 meters from the corvette, position from which he opened fire.

After an hour and a half of combat, the Esmeralda had not been hit by any projectile from the Huáscar, their shots were long, landing on the beach and injuring the population. Around ten in the morning, General Juan Buendía, head of the Peruvian troops in Iquique, had 4 Blakely mountain cannons brought to the beach with which he began firing at the Esmeralda. One grenade killed three men and another wounded three others. In total, he fired 60 shots and several rifle shots. The situation became untenable for the Chilean corvette, so Prat decided to change his location 1,000 meters further north. As the movement began, a grenade from the Huáscar penetrated her port side, exiting on her starboard side, causing a fire in the wardroom that was promptly controlled.

- First spur and approach of Prat

Once in its new position, the corvette could not move and defended there an hour and a half until its sinking.

<p He headed his bow towards the port side of the Emerald . Prat tried to dodge the blow and closing the rod to port failure to dodge the blow he received at the height of the Mesana stick without major damage. When both ships collide, the monitor Huáscar fired its ten -inch cannons (300 pounds) at a short distance, producing the death of 40 or 50 sailors and soldiers.The spur of the Huáscar the monitor.

Seeing the enemy ship cover at his feet, Prat shouted:

"To board, boys!"Arturo Prat. 21 May 1879

Prat jumped onto his enemy deck followed by Sergeant Juan de Dios Aldea and sailor Arsenio Canave who died on the deck of the Huáscar.

Once on board, Prat, armed with a saber and a revolver, advanced towards the conning tower; On the way to her, he killed the signal officer, Second Lieutenant Jorge Velarde. Advancing to port of Coles' tower, he was hit by bullets in one of his knees. A sailor came out on deck and killed him. In turn, Sergeant Aldea fell wounded by a rifle discharge on the deck. Grau made an effort to save Prat's life but it was too late.

- Second spur and approach of Serrano

Commander Grau wanted to give his adversaries time to surrender, so he withdrew the Huáscar after the ram. In the Esmeralda, 1st Lieutenant Luis Uribe Orrego took command, who called a meeting of officers and they decided not to surrender; as Midshipman Zegers climbed the mizzenmast to nail the flags.

Seeing that the truce was not working, Grau decided to spur the Esmeralda again, launching himself at full speed on her, now from the starboard side. Uribe tried to maneuver just like Prat and managed to present his side obliquely to the spur of the monitor Huáscar , but this time a leak opened up, pouring into the magazine and the machines. The ship was left without steering and without more ammunition than what was on deck.

Again, the cannons of the Huáscar fired at close range, killing several crew members; among them, the engineers and stokers who came out on deck and razed the officer's room, converted into an infirmary. A second boarding attempt was made by another twelve Chilean crew members, under the command of First Lieutenant Ignacio Serrano, carrying rifles and machetes, which was also unsuccessful, falling on the deck of the monitor.

- Third spur

After 20 minutes, the third impact was made with a spur in the sector of the mizzen pole, accompanied by two cannon shots. At this moment, a third collision occurred, a fact little known, in which two sailors jumped onto the deck of the Huáscar. One of them has been identified as the helmsman Eduardo Cornelius who managed to survive the combat and tell his story.

- Singing of the Emerald

The sloop, with the third impact, tilted forward and began to sink. As the ship listed, midshipman Ernesto Riquelme, shouting cheers to Chile, fired the last shot.

At 12:10 that day, the Esmeralda disappeared from the surface of the sea with her Combat Flag raised.

In total, the Huáscar fired 47 projectiles and was hit by 6 bombs and 23 bullets. The Chileans claimed 143 deaths. The Peruvians lost Second Lieutenant Jorge Velarde and seven sailors were wounded. Before advancing to meet with the Independencia, Grau ordered the rescue of the 57 shipwrecked of the Esmeralda.

Epilogue

The survivors of the Esmeralda were handed over to the military authorities in the port of Iquique. The surviving sailors were taken as prisoners to the Peruvian town of Tarma and were exchanged for prisoners of the Huáscar on a man-for-man and degree-by-degree basis at the end of December 1879. About the situation of the survivors de la Esmeralda, Jorge Hunneus of the Chilean Ministry of Foreign Affairs wrote to the British vice-consul in Iquique, expressing the generosity with which Peru treated the imprisoned sailors and which he hopes to reciprocate.

After the combat, Admiral Grau ordered that Prat's personal belongings—his personal diary, his uniform, and his sword, among others—be returned to his widow. Together with them, Carmela Carvajal received a letter from the Peruvian admiral. In this letter, Grau emphasizes the personal quality and nobility of his rival. In response, Carmela Carvajal wrote him a letter thanking him for this gesture. This fact, added to the rescue of the survivors of the Esmeralda, earned Grau the nickname "The Knight of the Seas".

The bodies of Arturo Prat and Serrano were buried on Thursday, May 22, in the Iquique cemetery, with the donation of the Spanish citizen Eduardo Llanos and other members of his neighborhood to cover the burial expenses.

The news reached Valparaíso, Chile, by submarine cable. On Saturday, May 24, the details of the combat in Iquique and the death of Prat and, in addition, the sinking of the Esmeralda, were recently revealed in Santiago. According to modern Chilean historians, it was from that moment that the feeling of the Chilean people towards the conflict changed. Affirming[who?] that: "A war little understood by the people, suddenly became an occasion to emulate the heroism of Prat", which is why a large number of Chileans voluntarily went to the barracks to enlist and participate in the conflict.

The battle at Iquique was a Peruvian victory because it temporarily culminated in the blockade of the port, a Chilean ship sunk and another put to flight. But, taking the actions of Iquique and Punta Gruesa as a whole, it was a Pyrrhic victory, since the oldest ships of the Chilean Navy, a schooner and a wooden frigate, fought against two Peruvian armored vessels. The end result was one of them running aground and sunk, and with it, fifty percent of Peru's offensive naval power in the war.

For its part, the damage caused to the Huáscar by the fire from the Esmeralda was minimal, due to the shielding of the monitor.

Tributes

In 1888, the remains of Commander Arturo Prat were transferred to Valparaíso, where they were buried in a monument built by popular subscription. In this monument, the greatest Chilean naval heroes rest, and it is there where every year, on the day of naval glories, with the presence of the President of the Republic, the figure of Prat and his crew are honored with military parades.

May 21 has been a holiday in Chile since 1915 and was the date of the Annual Account of the President of the Republic before the full Congress from 1926 to 2016. As of 2017, the presidential public account is takes place on June 1 of each year.

The American historian William Sater notes the "material uselessness" of his action in Iquique; however, he points out that "by transcending from the physical to the spiritual, he created rules of conduct that brought victory to his nation in the war and that were internalized by the following generations." That at least was the purpose of Chilean national education that has permanently set him up as a model to imitate.

For his part, Admiral Miguel Grau Seminario is remembered both in Peru and Chile for his nobility and chivalry in combat. Some streets in Chile are named after Almirante Grau. His actions during the War of the Pacific made him the greatest naval hero of the Peruvian Navy. Miguel Grau is also considered a naval hero in Bolivia.

Contenido relacionado

Ramiro I of Aragon

Pedro de Heredia

Mozarabic