Natural law

The natural law is an ethical and legal doctrine that postulates the existence of rights based or determined in human nature. It advocates the existence of a set of universal, previous, superior and independent rights to written law, positive law, customary law, coming to give the foundation for the obligation of the norm and the legitimacy of power. The group of thinkers or schools of thought that are inspired by natural law is called natural law.

Introduction

Under the term "iusnaturalist" is grouped a set of theories on law and justice that differ in methods and forms of foundation, but that coincide in maintaining that there are certain mandates or principles that by definition belong to the law, of so that if positive law does not consecrate and sanction them, it is not true law. In other words, natural law or "natural law" theories affirm that the legitimacy of positive laws, which are the set of rules actually in force in a State, ultimately depend on their agreement with natural law. In Johannes Messner's definition, "natural law is the order of existence" (Naturrecht ist Existenzordnung). For Messner, natural law contains specific principles and denying this implies contradicting human conscience..

For natural law, the validity of the law also depends on its justice (or material correctness) and that is why the main thesis of natural law can be summarized in the expression of Gustav Radbruch: "The extremely unfair law is not true law". Recent experiments also show that the sense of justice is innate in the human species and is the same in all beings that form it, even when they are barely fifteen months old.

Literature already shows the antinomy between human authority (the νόμος or nόmos) and the «unwritten laws», which come from the divine will (the ἄγραπτα νόμιμα or ágrapta nόmima) in the tragedy Antigone by Sophocles, whose verses support those who defend the existence of an absolutely valid superior right and prior to human laws. Likewise, the invocation of natural law served the American jurists of the 18th century to proclaim and authenticate the independence of their country with respect to the United Kingdom, alleging their right to resist oppression, "consequence of all other rights" which also accept the French constitutions of 1789 and 1793.

Radbruch's philosophy of law derives from neo-Kantianism, which postulated that there is a break between being (Sein) and ought to be (Sollen), or between facts and values. Likewise, there is a sharp division between the explanatory, causal sciences, such as the natural sciences, and the interpretative or comprehensive sciences ("spiritual sciences"). The science of law would be situated, for Radbruch, among the sciences of the spirit, since it is not limited to describing a reality, but rather aspires to understand a value-laden phenomenon (law). Legal science is thus distinguished from both the sociology of law and the philosophy of law.

The core of Radbruch's philosophy of law consists in the separation between positive law and the idea of law. The idea of law is defined by the triad consisting of: justice, utility and security. Radbruch's formula is based on this triad.

Radbruch assumed for most of his life a rationalist and relativist stance, defining relativism as "the ideological assumption of democracy." No ideology is provable or refutable, and all deserve equal respect. However, after 1945 Radbruch experiences an evolution in his theoretical positions, as a consequence of the fall of the Nazi regime, the disclosure of his crimes and the need to judge those responsible for them. He then admits the possibility of a "supralegal right"; or "nature of things" that prevails over openly unfair and arbitrary laws. Some authors, such as Lon Fuller, interpret this as a change in position from positivism to natural law; others, such as Erik Wolf, have defended the essential continuity of Radbruch's thought.

As a prominent witness of his time, when analyzing the National Socialist legal system, Gustav Radbruch confirms an indisputable fact: the legislator can make extremely unfair laws. And as a consequence of the above, this author postulates the existence of a "supralegal" which is a limit to the right of the State. Such supralegal right behaves as an index or parameter of the material validity of national norms and is openly opposed to the absolute relativity of justice. But, for Radbruch, not any injustice invalidates a positive norm, only extreme injustice: "The extremely unfair law is not true law."

A consequence that is usually drawn from some natural law positions, particularly the Thomist and the Lockean, is the following: "It would be legitimate to resist authority when trying to impose compliance with a law that is not compatible with the natural law".

Thesis

The main thesis of natural law can be summarized as follows:

- There are certain principles concerning the good or evil of a universal character: natural laws or natural rights, which act as a supra-legal framework.

- The content of these principles is man-conscious by reason.

- The right rests on the moral (moral, of the gene. Latin mōris, 'costumbre', and from there mōrālis, 'relative to uses and customs').

- If these principles are not collected or sanctioned by the positive legal order, the latter cannot be considered a true legal order.

This last point, however, is not treated uniformly by all natural law authors. Obviously, for some, not any omission or contravention of the moral principles incorporated into the law entails the invalidity of the positive legal system.

For his part, Robert Alexy explains that the application of the so-called "Radbruch formula" ("extremely unjust law is not true law") can be understood in two ways, corresponding to what he calls the "radiation thesis" and the "collapse thesis", respectively.

Thus, according to the first, the extreme injustice of certain fundamental norms of the legal system would lead by way of contagion to the invalidity of the entire legal system.

According to the second thesis, the "collapse thesis," the formula must be applied to particular legal norms, so that the only way in which a positive legal order could be considered invalid in its entirety It would take place because there were many extremely unfair particular rules in it, so that the elimination of each and every one of them would leave the legal system without sufficient rules to be able to regulate social relations. Alexy states that the first thesis, the "irradiation thesis," should be discarded, in consideration of legal certainty. Consequently, he only admits the second form of application of the Radbruch formula.

Historical notions

Natural law, unlike positive law, is not written, but emanates from the same human species, from the same human condition. It is inherent and equal in each of its members regardless of their social position, ethnicity and nationality, or any other consideration. It is universal and oblivious to historical changes. Some of its mandates also have a written expression, such as the Golden Rule. The first modern formulations of the concept of natural law come from the School of Salamanca and have been taken and reformulated by the theorists of the social contract (Thomas Hobbes, John Locke, Jean-Jacques Rousseau) from the new notion for the time of & #34;state of nature".

Classical natural law

Greece and Rome

The remote origins of the idea of natural law can be found in Plato (IV century B.C.), particularly in his work República and Laws. In his Nicomachean Ethics , Aristotle, for his part, distinguishes between legal or conventional justice and natural justice. The latter refers to what "everywhere has the same force and does not exist because people think this or that". In the same place, Aristotle insists that natural laws are not immutable, since in human nature itself there are natural changes due to internal principles of development. And the human being has rationality as a fundamental feature that allows us to inquire into characteristically human life. On the other hand, in his other work Politics he also establishes that man's reasoning is a natural law and determines different precepts such as freedom (and the justification of slavery by natural law, since for him there are inferior and superior men) [citation needed].

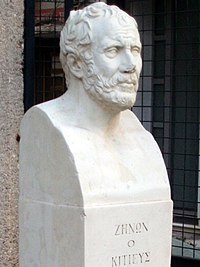

This aspect of rationality will be taken up by Stoicism from another point of view. Human nature is part of the natural order. Human reason is a spark of the creative fire, of the logos, which orders and unifies the cosmos. The natural law is like this: the law of nature and the law of human nature, and this law is reason. And that reason has been implanted by divinity or the gods. And since reason can be perverted to serve interests outside of reason itself, it was said that the natural law is the law "of right or sound reason".

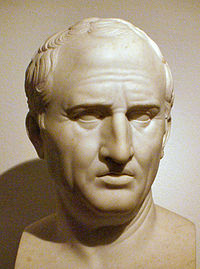

In this way, Cicero (I century BC) will affirm that for the educated man the law is the conscious intelligence, whose natural function is to prescribe right conduct and prohibit misconduct—is the mind and reason of the intelligent man, the standard by which justice and injustice are measured (Laws, 1.SAW)-. And a man owes to all others and is due to all others: Non nobis solum nati sumus ("we are not born for ourselves", De officiis, 1:22). Cicero writes in the context of the formation of Roman law, which is fundamental to the idea of the rule of law, and has Stoicism as its intellectual source. Cicero in De re publica (III, 17) will write:

There is a true law, the right reason, according to nature, universal, immutable, eternal, whose mandates stimulate duty and whose prohibitions depart from evil. Whatever he commands, whatever he prohibits, his words are not vain to the good, nor powerful to the bad. This law cannot be contradicted by another, or repealed in any of its parts, or abolished in whole. Neither the Senate nor the people can free us from obedience to this law. He does not need a new interpreter, or a new organ: it is not different in Rome than in Athens, nor tomorrow other than today, but in all nations and in all times this law will always reign unique, eternal, imperceible, and the common guide, the king of all creatures, God himself gives the origin, the sanction and the publicity to this law, that man cannot be unaware without fleeing from himself, without any other cause,

The pure naturalistic conception also reappears in a famous text attributed to Ulpiano: "Ius naturale est quod natura omnia animalia docuit". highest when developed in the 2nd and 3rd centuries c. C. a positive law, the ius gentium, more appropriate to govern the multiple peoples of the Roman Empire, so that a jurist from the second century, Gaius, affirms that natural law can be identified with that of people (ius gentium vel naturale). Thus, Ángel Latorre summarizes that:

- At the top of the legal system is the ius naturale, understood as id quod semper aequum ac bonum est; come after ius gentiumI mean, who human people utuntur and finally the ius civile That's quod quisque populus ipse sibi ius constituciónt and it is ipsius proprium civitatis.

Christianity

Christianity continued Stoic conceptions. In the Middle Ages, Thomas Aquinas will start from the idea of Cicero reformulating the idea of divine law: God has established an eternal legislation for the natural world and the human world, and that is what we know as natural law. Saint Thomas Aquinas maintains in the first place that there is an order of the instincts of the human species and secondly that there are ends indicated to them by nature itself (teleology), for example those of conservation, nutrition, procreation, of the instincts of community life in the family and in the State.

Jaime Balmes understood that human morality is based on and participates in God's perfect morality, which configures the first point of natural law. "God, seeing from eternity the current world and all the possible ones, also saw the order to which the creatures that composed them should be subject. [...] the impression of this rule in our spirit [...], is what is called natural law. Among the prescriptions of this law, the love of God appears in the first line; the moral order in the creature could not be founded on anything else: since God's love for himself is morality by essence, the participation in this morality should also be the participation in this love' 39;.

Modern Natural Law

It is usually affirmed that the fundamental difference between classical natural law and modern natural law lies in the emphasis that each of them places on the notion of natural law and subjective law, respectively. Thus, while modern natural law doctrines are developed and articulated fundamentally from the notion of law as a moral faculty (natural law), classical natural law theories would do so from the notion of natural law.

Also, although the transition between both forms of natural law was gradual, it is accepted that the work of Hugo Grocio constitutes the milestone that marks the separation between classical natural law and modern natural law.

Jesuits such as Francisco Suárez (1548-1617) had already asserted the autonomy of natural law and in the 17th century rationalism deals with natural law with authors like Hugo Grocio. In the midst of the European religious wars, these authors attempt to provide a moral framework for nations that guarantees peace:

Certainly, what we have said would take place, even if we admit something that cannot be done without committing the greatest crime, such as accepting that God does not exist or that God does not care about the human.

Thomas Hobbes, also in the 17th century, defined in his Leviathan natural law as:

The freedom that each one has to use his own power to his own arbitrary for the preservation of his nature, that is, his life, and consequently to do anything that, according to his judgment and reason, he conceives as the best means for that purpose.

Natural law in the philosophy of law was defended by the aforementioned Thomas Aquinas (theological natural law) and in the hands of rationalist natural law gave rise to the theories of social contract or contractualism. Spanish Krausism gave a great boost to the philosophy of natural law in the Hispanic sphere when Francisco Giner de los Ríos published his Principles of Natural Law (Madrid, 1873), and in fact natural law was the doctrine most influential until legal positivism superseded it through theoretical positions such as Hans Kelsen's Pure Theory of Law. At the beginning of the XIX century, the Historical School of Law spread in Europe, which considers historical traditions and customary law as the sources of every legal system, ironing out the differences with positivism. Its main author is Friedrich Carl von Savigny. After the Second World War, the influence of natural law revived, as a consequence of the questioning of the obedience of citizens to totalitarian political regimes, which was attributed, in part, to iuspositivist doctrines. An expression of this is the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

One of the current exponents is John Finnis, with his theory of central and peripheral cases.

A current political philosophy or political doctrine that bases its existence on positive law is Rothbardian libertarianism or anarcho-capitalism (Murray Rothbard), which in his works For a New Liberty and The Ethics of Liberty affirm the need for a universal and common law for the coexistence in freedom of individuals. It uses previous philosophy developed by John Locke and classical liberals.[citation needed]

In Christianity

In Christianity, morality is considered universal, since in the Bible, specifically in the New Testament, it is described that all men (even Gentiles) have a "law written in their hearts", which is interpreted as a natural law that was given by God, which is manifested as an innate morality, and which constitutes the spiritual root of conscience human.

Likewise, nos. 1954 to 1960 of the Catechism of the Catholic Church deal with the natural moral law.

Thomas Hobbes

Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679) included a discussion of natural rights in his moral and political philosophy. Hobbes's conception of natural rights extended from his conception of man in a 'state of nature'. Thus he argued that the essential natural (human) right was to "use his own power, as he himself willed, for the conservation of his own nature;" that is, of his own life; and consequently, to do anything, that in his own judgment and reason, he will conceive as the most apt means for it & # 34;. (Leviathan. 1, XIV)

Hobbes clearly distinguished this "freedom" nature of the "laws" natural, generally described as "a general precept or rule, discovered by reason, by which a man is forbidden to do that which is destructive of his life, or to take away the means of preserving his life, and omits that so he believes that it can be better preserved". (Leviathan. 1, XIV)

In his natural state, according to Hobbes, man's life consisted entirely of liberties and not laws: "It follows that in such a condition, each man has a right to everything, even over the bodies of others. And therefore, as long as this natural right of every man to everything endures, there can be no security for any man... of living as long as Nature ordinarily allows men to live. (Leviathan. 1, XIV)

This would inevitably lead to a situation known as the "war of all against all," in which human beings kill, steal and enslave others to stay alive and because of their natural lust for & #34;gain", "security" and "reputation".. As such, if humans wish to live in peace, they must give up most of their natural rights and create moral obligations to establish a civil and political society. This is one of the earliest formulations of the theory of government known as the social contract.

Hobbes opposed the attempt to derive rights from the " natural law ", arguing that law ("lex") and law ("jus"), although often confused, mean opposite things, referring to law obligations, while rights refer to the absence of obligations. Since by our (human) nature we seek to maximize our well-being, rights are prior to law, natural or institutional, and people will not follow the laws of nature without first submitting to a sovereign power, without which all ideas of right and wrong are meaningless: 'Therefore, before the names Just and Unjust can take place, there must be some coercive Power, to compel men alike to their Covenants...acquire, in recompense of the universal Law that they abandon: and such power does not exist before the erection of the community". (Leviathan . 1, XV)

This marked a major departure from medieval natural law theories that gave priority to obligations over rights.

John Locke

John Locke (1632–1704) was another prominent Western philosopher who conceptualized rights as natural and inalienable. Like Hobbes, Locke believed in the natural right to life, liberty, and property. It was once assumed that Locke greatly influenced the American Revolutionary War with his writing on natural rights, but this claim has been the subject of lengthy dispute in recent decades. For example, historian Ray Forrest Harvey stated that Jefferson and Locke were "two poles apart"; in his political philosophy, as evidenced by Jefferson's use in the Declaration of Independence of the phrase "pursuit of happiness"; instead of "property". More recently, the eminent legal historian John Phillip Reid has deplored the "misplaced emphasis on John Locke" of contemporary scholars, arguing that American revolutionary leaders viewed Locke as a commentator on established constitutional principles. Thomas Pangle has defended Locke's influence on the Founding of the United States, stating that historians who argue otherwise misrepresent the classical Republican alternative that revolutionary leaders say they espoused, misunderstand Locke, or point fingers at someone. more than he was decisively influenced by Locke. This position has also been held by Michael Zuckert.

According to Locke, there are three natural rights:

- Life: Everyone has the right to live.

- Freedom: everyone has the right to do whatever he wants while he does not conflict with the first right.

- Heritage: everyone has the right to own everything he creates or gains through donation or trade, provided that he does not conflict with the first two rights.

In developing his concept of natural rights, Locke was influenced by the societal accounts of Native Americans, whom he viewed as natural peoples living in a "state of liberty" perfect, but "not in a state of license". He also informed his conception of the social contract. Although he doesn't say it outright, his position implies that, even in light of our unique characteristics, we should not be treated differently by our neighbors or rulers. "Locke argues that there is no natural characteristic sufficient to distinguish one person from another... of course, there are many natural differences between us" (Haworth 103). What Haworth takes from Locke is that John Locke was obsessed with supporting equality in society, treating everyone as equal. However, he highlights our differences with his philosophy that we are all unique and important to society. In his philosophy, it is emphasized that the ideal government must also protect everyone, and provide rights and freedoms to all, because we are all important to society. His implicit thinking of freedom for all applies most strongly in our culture today. Beginning with the civil rights movement and continuing with women's rights, Locke's call for just government can be seen as influencing these movements. Usually, his ideas are only seen as the basis of modern democracy; however, it is not unreasonable to recognize Locke in social activism throughout the history of the United States.

In founding this sense of freedom for all, Locke was laying the foundation for the equality that exists today. Despite the apparent misuse of his philosophy in the early days of American democracy. The civil rights movement and the suffrage movement denounced the state of American democracy during their challenges to the government's vision of equality. It was clear to them that when the designers of democracy said it all, they meant that all people should receive those natural rights that John Locke treasured so deeply. "a state also of equality, in which all power and jurisdiction are reciprocal, without anyone having more than another" (Lock II, 4). Locke in his articles on natural philosophy makes it clear that he wants a government in which all are treated equally in liberties especially. "Locke's views on toleration were very progressive for the time" (Connolly). Authors like Jacob Connolly confirm that for them Locke was far ahead of his time with all this progressive thinking. It's that his thinking fits our current state of democracy where we strive to make sure everyone has a say in government and everyone has a chance at a good life. Regardless of race, gender, or social position, beginning with Locke, it became clear that not only government should grant rights, but rights to everyone through its social contract.

The social contract is an agreement between the members of a country to live within a shared system of laws. Specific forms of government are the result of decisions made by these people acting in their collective capacity. The government is instituted to make laws that protect the three natural rights. If a government does not adequately protect these rights, it can be overthrown.

Some relevant representatives of Natural Law

- Plato

- Aristotle

- Cythium Zenon

- Cicero

- Seneca

- Thomas Aquinas

- Francisco de Vitoria, Domingo de Soto and the School of Salamanca

- Francisco Suárez

- Hugo Grocio

- Thomas Hobbes

- Christian Wolff

- Thomas Jefferson

- John Locke

- Jean-Jacques Rousseau

- Immanuel Kant (Vernunftrecht)

- Gottfried Achenwall

- Robert Alexy

- Jean Barbeyrac

- Benedict XVI

- Luigi Taparelli d'Azeglio

- Emil Brunner

- Adam Friedrich von Glafey

- Johann Christoph Hoffbauer

- Ludwig Julius Friedrich Höpfner

- Hans-Hermann Hoppe

- Gottlieb Hufeland

- Johann Adam von Ickstatt

- Karl Anton von Martini

- Johannes Messner

- Robert Nozick

- Oliver O’Donovan

- Samuel von Pufendorf

- Gustav Radbruch (after 1933)

- Ayn Rand

- Murray N. Rothbard

- Lysander Spooner

- Christian Thomasius

- Franz von Zeiller

- John Finnis

- Erick M. Rovers

Critics of natural law

- Max Stirner

- Jeremy Bentham

- Friedrich Nietzsche

- Karl Barth

- H.L.A. Hart

- Norbert Hoerster

- Hans Kelsen

- Gustav Radbruch (up to 1933 – discussed)

- Alf Ross

- Peter Stemmer

- Ernst Topitsch

- Norberto Bobbio

Contenido relacionado

Bank Commission

Absolute monarchy

Death penalty (disambiguation)