Nanjing massacre

The Nanjing Massacre (Chinese: 南京大屠殺, pinyin: Nánjīng Dàtúshā; Japanese: 南京大虐殺, Nankin Daigyakusatsu), Also known as the rape of Nanking, it refers to the crimes committed between the end of 1937 and the beginning of 1938 by the Imperial Japanese Army in the city of Nanking, then capital of the Republic of China, during the second Sino-Japanese war.

The Japanese Army moved north after capturing Shanghai in October 1937, and conquered Nanjing in the Battle of Nanjing on December 13, 1937. The Chinese Government, led by Chiang Kai-shek and the Army commanders Chinese nationalist (Kuomintang), abandoned the city before the entry of the Japanese army, leaving behind thousands of Chinese soldiers trapped in the walled city. Many of them took off their uniforms and escaped to the so-called Safety Zone, prepared by foreign residents of Nanjing. The massacre occurred during a six-week period following the occupation of the city. This historical episode remains a controversial political issue, and represents an obstacle in Japan's diplomatic relations not only with China but also with other East Asian nations, such as South Korea.

War crimes committed during this episode include pillage, mass rape of women, and the killing of civilians and prisoners of war. It is estimated that between 40,000 and more than 300,000 Chinese died. In 1946, the Tokyo War Court ruling estimated that more than 200,000 Chinese died in the massacre. In the death sentence issued against the Japanese army commander in Nanjing, General Iwane Matsui, the figure was set at 100,000. In December 2007, some newly released US government documents, which until then had been a state secret, they considered the total number of dead to be 500,000, taking into account what happened around the city before its capture.

Chinese historiography generally maintains that 300,000 people were murdered during the massacre. In Japan, public opinion is divided on the matter, especially among conservatives, for whom the Nanjing massacre would have been exaggerated.

Historical background

The massacre of Nanjing, then the capital of the Republic of China, occurred after its fall to the Imperial Japanese Army on December 13, 1937. The duration of the massacre is not clearly defined, although the violence continued well into the the six weeks arriving at the beginning of February 1938.

During the occupation of Nanjing, the Japanese military committed numerous atrocities, including raping, looting, burning, and executing prisoners of war and civilians. Although the executions began under the pretext of eliminating Chinese soldiers disguised as civilians, it is claimed that a large number of innocent men were intentionally identified as enemy combatants and executed. Large numbers of women and children were also killed as rape and murder spread.

On the other hand, in August 1937, in the middle of the Second Sino-Japanese War, the Imperial Japanese Army encountered strong resistance and suffered heavy casualties in the Battle of Shanghai. The offensive was bloody, and both sides ended up worn down in hand-to-hand combat.

On August 5, 1937, Hirohito personally ratified his army's proposal to remove international law restrictions on the treatment of Chinese prisoners. This directive also forced staff officers to stop using the term "prisoner of war."

On the way from Shanghai to Nanjing, Japanese soldiers committed a large number of atrocities, so the Nanjing massacre was not an isolated incident. The most famous event was the “contest to kill 100 people using a katana.”

By mid-November, the Japanese had captured Shanghai with the help of air and naval bombardments. The General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo decided not to expand the war, due to the serious casualties incurred and the depressed morale of the troops.

Approach to Nanjing

As the Japanese Army approached Nanjing, Chinese civilians left the city en masse, and the country's militia carried out a scorched earth campaign, focused on destroying anything that might be of value to the invading Japanese army.. Targets, inside and outside the city walls, such as military barracks, private residences, government offices, such as the Chinese Ministry of Communication, forests and even entire towns, were reduced to ashes, at an estimated value of 20 to 30 million of dollars (1937).

On December 2, Emperor Shōwa appointed one of his uncles, Prince Yasuhiko Asaka, as commander of the invasion. It is difficult to establish whether, as a member of the imperial family, Asaka had a higher status than General Iwane Matsui, who was officially commander-in-chief, but it is clear that, as a senior officer, he had authority over everyone, commanders, lieutenant generals such as Kesago Nakajima and Heisuke Yanagawa. On December 8, Chiang Kai-shek left the city, entrusting the defense to Tang Shengzi.

Nanjing Security Zone

Many Westerners were living in the city for commercial reasons or, on missionary trips with different religious groups. When the Japanese military began launching airstrikes on Nanjing, most Westerners and all journalists returned to their respective countries, except for 22 people. German Siemens businessman John Rabe preferred to remain in the city and formed the International Committee for the Nanjing Security Zone. Rabe was chosen as its leader (presumably due to his status as a Nazi and thanks to the Anti-Comintern Pact signed between the Empire of Japan and Germany). This committee established the Nanjing Security Zone in the western part of the city. The Japanese Government had agreed not to attack those parts of the city that did not have Chinese militia. For this reason, members of the International Committee for the Nanjing Security Zone convinced the country's government to remove all its troops from their area.

The Japanese respected the Safety Zone to a certain extent; No projectiles hit that part of the city, except for a few stray shots. During the chaos that followed the attack on the city, some people were killed in the Safety Zone, but the atrocities committed in the rest of the city were vastly worse.

John Rabe is known as the "Oskar Schindler of Nanjing" who, with his humanitarian actions, managed to save the lives of some 200,000 Chinese. In 1997, the diaries written by Rabe about the events in Nanjing were published, confirming the massacre.

History and facts

According to the Tokyo War Court, estimates made at a later date to indicate the total number of civilians and prisoners of war killed in and around Nanjing during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation gave a figure of more than Two hundred thousand. That these estimates are exaggerated is not confirmed by the fact that burial societies and other organizations counted more than one hundred and fifty-five thousand burials, most with their hands tied behind their backs. These figures exclude those incinerated or swept away by the river current. The magnitude of the atrocities is debated between China and Japan, with the numbers, ranging from some Japanese claims of several hundred, to China's claim of a non-combatant death toll of three hundred thousand.

Japanese researchers consider an approximate value of between one hundred thousand and two hundred thousand civilian murders. Other nations, the number is between one hundred and fifty thousand and three hundred thousand. This number was disclosed in January 1938 by the Australian Harold John Timperly, a journalist witness, based on reports from other contemporary witnesses. Other sources, including Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanjing, also count three hundred thousand. Furthermore, on December 12, 2007, the US government declassified additional documents that revealed a balance of around five hundred thousand in the area around Nanjing prior to the occupation.

In addition to the number of victims, some critics still dispute whether the atrocity occurred. While the Japanese government has acknowledged the incident, some Japanese have supported the nationalists, in part using the Imperial Japanese Army's demonstrations at the International Military Criminal Tribunal for the Far East, that the death toll was military in nature and that none of those civil atrocities occurred. These claims have been questioned by various data, supported by statements in Court by foreign citizens, other eyewitnesses and by photographic and archaeological evidence that would demonstrate that civilian deaths occurred.

Condemnation of the massacre is an important element of Chinese nationalism. In Japan, however, public opinion on the seriousness of the massacre remains widely divided. This is demonstrated by the fact that, while some Japanese commentators refer to it as the "Nanking Massacre" (南京大虐杀, Nankin daigyakusatsu), others use the more ambivalent term "Nanking Incident" (南京事件, Nankin jiken). However, this term may also refer to an incident that occurred in Nanjing in 1927 during the Nationalist Northern Expedition's takeover of the city, in which foreigners in the city were attacked.

The 1937 massacre and the extent of its coverage in textbooks remains a point of controversy and controversy in Sino-Japanese relations.

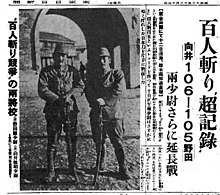

- Masacre Competition

On December 13, 1937, the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun newspaper and its analogue the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun covered a "competition" between two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai (向井敏明) and Tsuyoshi Noda (野田毅), both from the troops of the 16th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, in which they are described as competing with each other to be the first to kill by beheading 100 people with a katana before the taking of Nanjing. From Jurong and Tangshan (two cities in Jiangshu Province, China) to Zijin Mountain, Tsuyoshi Noda had killed 105 people, while Toshiaki Mukai murdered 106 people. Both officers supposedly surpassed their goal during the heat of battle, making it impossible to determine who had won the contest; Therefore it was decided to start another contest, with the goal of reaching 150 deaths. After Japan's surrender, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda were arrested and shot in Nanjing as war criminals.

Massacre

Eyewitness accounts from both Westerners and Chinese in Nanjing record that, over the course of six weeks after the city fell, Japanese troops engaged in a wave of rapes, murders, robberies, looting, arson, and other crimes. of war. Proof of this remains the diaries of some foreigners such as John Rabe and the American Minnie Vautrin, who chose to stay in order to protect Chinese civilians from such atrocities. Other accounts include first-person testimonies from survivors of the Nanjing massacre, reports from eyewitnesses such as journalists (Western and Japanese), as well as the field diaries of military personnel. American missionary John Magee offered a 16 mm film tape and first-hand photographs of the Nanjing massacre.

On November 22, a group of foreign expatriates led by Rabe had been tasked with forming the 15-member International Committee and mapping out the Nanjing Safety Zone in order to protect civilians in the city, where the population was 200,000 to 250,000. Rabe and the American missionary Lewis SC de Smythe, secretary of the International Committee and professor of sociology at Nanjing University, recorded the actions of the Japanese troops and the complaints presented to the Japanese embassy.

- Massacre of civilians

After the capture of Nanjing on December 13, 1937, the Imperial Japanese Army murdered more than 250,000 residents of the city, a figure difficult to calculate precisely due to the many bodies deliberately burned, buried in pits, or thrown into the Yangtze River. Campbell, in an article published in the journal Sociological Theory, has described the Nanjing massacre as a genocide, taking into account the fact that residents were killed en masse, despite the positive outcome in the battle.

Several foreign residents who were in Nanjing at the time of the events recorded their experiences of what was happening in the city:

The American doctor Robert O. Wilson, in a letter to his family: "the massacre of the civilian population is terrible. He could go on recounting pages of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Two bayoneted corpses are all that remain of seven street sweepers who were sitting in their headquarters, when the Japanese soldiers arrived without warning and killed five of their members and wounded two, who were able to go to the hospital."

Missionary John G. Magee, in a letter to his wife: "not only did they kill all the prisoners they could find, but also a large number of civilians of all ages[...] Just the day before yesterday we saw a poor miserable man dead very close to the house where we are living."

Dr. Wilson, in another letter to his family: "they [Japanese soldiers], bayoneted a child, causing his death. I spent an hour and a half this morning trying to treat another eight-year-old boy who had five bayonet wounds, one of which penetrated the stomach, causing a portion of the omentum to remain outside the abdomen."

On December 13, 1937, John Rabe wrote in his diary: "It was not until we toured the city that we learned the magnitude of the destruction. We came across dead bodies every 100 or 200 yards. The bodies of the civilians I examined had bullet holes in their backs. These people had allegedly been killed from behind while fleeing. The Japanese march through the city in groups of ten to twenty soldiers and loot the stores (...) I have seen it with my own eyes, since they looted the cafeteria of our German baker Kiessling".

Hiroki Kawano, former military photographer, relates: "I saw all kinds of gruesome scenes... decapitated bodies of children lying on the ground. They made the prisoners dig a hole and kneel on the edge before being beheaded. Some Japanese soldiers were very skilled at their work and were careful to sever the head completely, but leaving a small strip of skin between the head and the body, so that when the head collapsed it would drag the body towards the hole. (Revolutionary Document, Vol. 109 - History Committee for the Nationalist Party, Taipei, China - 1987, p. 79; Yin, James and Young, Shi, p. 132).

"Starting on December 13, people were pierced with bayonets, divided with swords or burned. Nothing, however, was more ruthless than burying them alive. Those miserable howls, those desperate screams scattered in the vibrating air. We could still hear them seven miles away" (Three Months of Nanking's Ordeal, author Jiang Gong-gu).

"Victims buried alive (type of burial with only the head out) died long before the effects of starvation and worms began, however some were used as 'javelin-type' targets.; with bayonets, others were trampled by horses, some were watered with boiling water and others were crushed with tank tracks. (Bergamini, David. Japan's Imperial Conspiracy, William Morrow Company, Inc. New York, 1971, p. 36).

"At that time the company to which I belonged was based in Xiaguan. We used barbed wire to tie the captured Chinese into bundles of ten and keep them together on the road. Then we poured gasoline on them and burned them alive. I felt like I was killing pigs" (Kozo Tadokoro "First-hand Experience of the Nanking Massacre").

According to Navy veteran Sho Mitani, 'The Army used a trumpet call that meant "kill all fleeing Chinese." Thousands of them were taken away and executed en masse in an excavation known as the 'Trail of Ten Thousand Corpses', a ditch about three hundred meters long and five meters wide. Since no records are preserved, estimates of the number of victims buried in the ditch range from 4,000 to 20,000. Most scholars and historians consider the number to be around 12,000 victims.

Violations

Women and children were not safe from the horrors of the massacres. The International Military Criminal Tribunal for the Far East estimates that 20,000 women were raped, including girls and elderly women. A large part of these violations were systematized in a process where soldiers carried out a door-to-door search to find the victims, who were taken captive and raped. Women were often killed immediately after being raped by mutilation (their breasts were cut off) or by stabbing, either with the bayonet itself or with long bamboo sticks or other sharp objects that were inserted into the vagina. the victims so that they ended up bleeding to death. In the case of pregnant women after rape, they were often bayoneted in the belly, open cuts were made and the uterus was torn, allowing the fetus to be seen.

Two excerpts from writings dated December 15 and 18, 1937, that Robert O. Wilson, a surgeon at American University Hospital, sent to his family: "Let me relate some cases that have occurred in the last two days. Last night the house of one of the university's Chinese staff members was destroyed and two of his relatives were raped. Two young girls, around 16 years old, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. At the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people; The Japanese jumped over the wall, stole food, clothing and raped until they were satisfied.

There are also accounts of Japanese troops forcing families to commit acts of incest. Sons forced to rape their mothers, fathers forced to rape their daughters. In turn, the monks who had consecrated themselves to a life of celibacy were also forced to commit rape and have sexual relations with each other, for the amusement of the Japanese army.

According to estimates, there were around, at least, 1,000 cases of rape per night and as many during the day. In case of resistance or any indication of resistance, they are bayoneted, stabbed or shot. (James McCallum, letter to his family, December 19, 1937):

"Probably, there is no crime that has not been committed in this city today. Thirty girls were taken from language school last night, and today I heard heartbreaking stories from the girls who were taken from their homes last night (one of the girls was 12 years old), but... Tonight happened a truck in which there were eight or ten girls and, as it passed, they shouted 'Jiu ming! Jiu ming!": save our lives" (Minnie Vautrin the diary, December 16, 1937).

"Although no young woman or woman who could be considered attractive was not at risk, no woman was safe from violent rape or sexual exploitation, (some of these were filmed as "souvenirs" 34;) and the probable subsequent murder. Groups of 3 or 4 marauding soldiers would begin traveling around the city and stealing everything they considered stealable. They continued to rape women and girls and kill anyone who tried to resist, those who tried to flee from them or simply those who were in the wrong place at the wrong time. There were girls under 8 years old and old women over 70 who were raped in the most brutal way possible, brutally beating them." (John Rabe, German businessman, member of the Nazi party, inhabitant of the "Neutral International Security Zone of Nanking", Chang The rape of Nanking p.119).

Reverend James McAllum: "I don't know where to start or where to end. I have never had to hear anything of such brutality. Raped, raped, raped, we estimated at least a thousand cases per night and many during the day. People are hysterical... Many women are brought in morning, noon and night. It seems that the entire Japanese military is free to go where it wants and do what it wants.' (R. John and Zaide, Sonia M. The Tokyo War Crimes Trial: The Complete Transcripts of the Proceedings of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, 27 Vols.).

"We would be fine if we had just raped them, but I never asked for the matter to stop. Many times we stabbed them with bayonets or knives, because the dead do not speak, perhaps if we had only raped them we would see them as women, but when we killed them, we saw them as pigs" (Chang, The Rape of Nanking, p. 49-50).

A witness Li Ke-Hen reported: "There are many bodies on the streets, victims of gang rape and murder. They are all naked, their cut breasts show a terrible brown hole, some of the bodies have been bayoneted in the abdomen, with their intestines sticking out, some have a roll of paper or a piece of wood stuck in their vaginas.

Many women were raped and brutally murdered. The current scenario of this massacre was presented in detail in the documentary The Battle of China. The movie Nanking! Nanking! (in Spanish: Ciudad de vida y muerte) directed by the Chinese Lu Chuan and awarded the Golden Shell for Best Film at the 2009 San Sebastián Film Festival, It is a recreation of the story of the Nanjing Massacre.

The Government was very aware of the atrocities. On 17 January, Koki Hirota's Foreign Minister receives a telegram written by Manchester Guardian correspondent Harold John Timperley, which was intercepted by the occupation government in Shanghai. In this telegram, Timperley wrote:

"Since returning from Shanghai a few days ago, he reported on the atrocities committed by the Japanese army in Nanjing and other places. Reliable eyewitness accounts and letters from individuals whose credibility is beyond doubt are compelling evidence that the Japanese army behaved and continues to behave in a manner reminiscent of Attila, king of the Huns. No less than three hundred thousand Chinese civilians were murdered, in many cases in cold blood."

Extrajudicial execution of Chinese prisoners of war

On August 6, 1937, Japan's Imperial Army Ministry ratified its army's proposal to remove international law limitations on the treatment of Chinese prisoners. This directive also advised personnel officers to stop using the term 'prisoner of war'.

Immediately after the city's resistance was defeated, Japanese troops embarked on a determined search for former soldiers, in which thousands of young people were captured. Many were taken to the Yangtze River, where they were machine-gunned. What was probably the largest massacre of Chinese troops occurred along the banks of the Yangtze River on December 18 in what is called the 'Straw Rope Gorge Massacre'. The Japanese soldiers spent most of the morning tying up all the POWs with their hands together and arranging them into 4 columns; after which they opened fire on them. Unable to escape, the POWs could only scream in desperation. It took an hour for the sounds of death to stop, and even longer for the Japanese bayonets to finish finishing off each individual. Most were thrown into the Yangtze River. It is estimated that at least 57,500 Chinese prisoners of war were killed.

Japanese troops gathered thirteen hundred Chinese soldiers and civilians at Taiping Gate and killed them. The victims were blown up with landmines, and then doused with gasoline. Those who were left alive were later killed with bayonets. Some people were beaten to death. The Japanese also summarily executed many pedestrians in the streets, usually under the pretext that they might be undercover soldiers in civilian clothes.

F. Tillman Durdin and Steele Archibald, the American news correspondents, reported seeing the corpses of Chinese soldiers forming mounds up to twenty feet high at the gate of Nanjing Yijiang. Durdin, who worked for The New York Times, toured Nanking before his departure from the city. He heard the machine gun bursts and pistol shots of the Japanese soldiers, estimating about 200 in ten minutes. Two days later, in his report to The New York Times, he said that the alleys and streets were littered with the bodies of civilians, including women and children.

According to a testimony given by missionary Ralph L. Phillips: "I was forced to watch as the Japanese disemboweled a Chinese soldier, roasting his heart and liver and then eating him."

Robberies and fires

A third of the city was destroyed as a result of arson. Japanese troops reportedly burned the newly constructed government buildings as well as the homes of many civilians. There was considerable destruction of areas outside the city walls. The soldiers plundered the poor and the rich alike. The lack of resistance from Chinese troops and civilians in Nanking meant that Japanese soldiers were free to divide the city's valuables as they pleased. This led to widespread looting and robbery.

End of the massacre

Matsui and Asaka's retirement

At the end of January 1938, the Japanese army forced all refugees in the security zone to return to their homes, claiming to have "restored order." After the creation of the "zhengfu Weixin" (the collaborationist government) in 1938, order was gradually restored in Nanjing and the atrocities committed by Japanese troops had decreased considerably.

On February 18, 1938, the Nanking Safety Zone changed its name to "Nanking International Rescue Committee" and the Security Zone effectively stopped functioning. The last refugee camps were closed in May 1938.

In February 1938, both Prince Asaka and General Matsui were retired from service and returned to Japan. Matsui went into retirement, but Prince Asaka remained on the Supreme War Council until the end of the war in August 1945. He was promoted to the rank of general in August 1939.

War crimes tribunals

Shortly after Japan's surrender, the top officers in charge of the Japanese troops in Nanjing were put on trial. General Matsui was charged before the International Military Criminal Tribunal for the Far East for "deliberately and recklessly" their legal duty to "take appropriate measures to ensure compliance and prevent violations" given in the Hague Convention. Tani Hisao, the Lieutenant General of the Sixth Division of the Japanese army in Nanjing, was tried by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal. Other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanjing massacre were not tried. Prince Kan'in, chief of the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff during the massacre, had died before the end of the war in May 1945. Prince Asaka was granted immunity due to his status as a member of the imperial family. Isamu Chō, Prince Asaka's assistant and whom some historians believe he issued the order to "kill all captives", had committed suicide during the defense of Okinawa.

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East met in Ichigaya, Tokyo.

General Iwane Matsui.

General Hisao Tani.

Films about the Nanjing Massacre

- 1995 The Black Sun Mou Tun Fei.

- 1995 Don't cry. Wu Ziniu.

- 2007, Nankín Bill Guttentag and Dan Sturman.

- 2009, City of life and death from Lu Chuan.

- 2009, John Rabe (click on John Rabe) by Florian Gallenberger.

- 2011, The Flowers of War from Zhang Yimou.

Contenido relacionado

Ignacio Carrera Pinto

Battle of Raszyn

Tirpitz (1941)

Antonio Arcos

Provisional Irish Republican Army

![General Iwane Matsui.[12]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c1/Iwane_Matsui.jpg/166px-Iwane_Matsui.jpg)

![General Hisao Tani.[13]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c0/Tani_Hisao.jpg/208px-Tani_Hisao.jpg)