Mount Everest

Mount Everest is the highest mountain on the surface of planet Earth, with an altitude of 8,848 meters (29,029 feet) above sea level. It is located on the Asian continent, in the Himalayas, specifically in the Mahalangur Himal subrange; marks the border between China and Nepal, considered to be the highest border in the world. The massif includes the neighboring peaks Lhotse, 8,516 meters (27,940 ft); Nuptse, 7,855 m (25,771 ft) and Changtse, 7,580 m (24,870 ft).

Toponymy

Everest is known in Nepal as Sagarmāthā ('The Forehead of Heaven'), in Tibet as Chomolungma or Qomolangma (' Mother of the Universe') and in China as Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng.

A 1733 map of Tibet and Bhutan by French geographer and cartographer Jean Baptiste Bourguignon d'Anville records the Tibetan name for the mountain: Tchomour langmac, the phonetic representation for Chomolungma.

In the late 19th century, many European cartographers mistakenly believed that the native name of the mountain was Gaurishankar, which is a mountain between Kathmandu and Everest.

In 1865, the Royal Geographical Society gave Everest its official western name on the recommendation of Sir Andrew Waugh, British Surveyor General of India in honor of his predecessor Sir George Everest:

My respected chief and predecessor, Colonel Sir Geo. Everest, taught me to assign to each geographical object its true local or native denomination. I have always scrupulously adhered to this rule, as I have listened to all other principles established by that eminent teacher. But here is a mountain, most likely the highest in the world, without any local name we can discover, or whose native denomination, if any, will not be determined before we are allowed to penetrate in Nepal and approach this wonderful snowy mass. Meanwhile, privilege, as well as duty, is my duty to assign to this high pinnacle of our globe, a name by which it can be known among the geographers and become a familiar word among the civilized nations. By virtue of this privilege, in testimony of my affectionate respect for a venerated leader, in accordance with what I believe is the desire of all members of the scientific department, on which I have the honour to preside and perpetuate the memory of that illustrious master of precise geographical research, I have decided to name this noble peak of the Himalaya 'Mont Everest'.Andrew Scott Waugh, 11 over 1857.

Proceedings of the Royal Geographical Society of London IX: 345-351.

His mentor George Everest argued against this name in 1857 stating that the local population would have trouble pronouncing Waugh's proposed name. Despite his objections, Waugh's proposed name prevailed and in 1865 the The Royal Geographical Society officially adopted the name Mount Everest for the world's highest mountain. Interestingly, the current pronunciation of "Everest" (/ˈɛvᵊrᵻst/) differs from the original pronunciation of Sir George Everest's surname (/ˈiːvrᵻst/ EEV-rist).

The Tibetan name for Mount Everest is ཇོ་མོ་གླང་མ (AFI: [t͡ɕʰòmòlɑ́ŋmɑ̀] lit. "Mother of the universe") whose official transcription in Tibetan pinyin is Qomolangma. It is also popularly romanized as Chomolungma and (in Wylie) as Jo-mo-glang-ma or Jomo Langma. The Chinese transliteration is 珠穆朗玛峰 (t 珠穆朗瑪峰) whose pinyin transcription is Zhūmùlǎngmǎ Fēng ("Chomolungma peak"). With minor It is also often translated into Chinese simply as Shèngmǔ Fēng t 聖母峰 (s 圣母峰 lit. "Holy Mother Peak"). In 2002, the Chinese newspaper People's Daily published an article speaking out against the consistent use of the Western name 'Mount Everest', insisting that its Tibetan name 'Mount Everest' should be used. Qomolangma" based on the official transliteration of the local name in said language. The newspaper argued that British colonists had not discovered the mountain "for the first time", as it was well known to Tibetans and had been marked on Chinese maps since 1719.

In the early 1960s, the Nepalese government realized that Mount Everest had no Nepali name. This is so because the mountain was not known or named in Nepal, ie in the Kathmandu valley and surrounding areas, and he began to search for a name for it. The Tibetan name (of the Sherpas) was not acceptable as it went against the country's Nepalization policy, so a new one was invented, Sagarmatha (सगरमाथा), created by Baburam Acharya.

Altitude

In 1856, the Great Project of Trigonometric Surveying established the first published elevation of Everest, then known as Peak XV, at 8840 m a.s.l. no. m.. The current official altitude of 8848 m s. no. m., recognized by China and Nepal, was established in 1955 by an Indian study and confirmed in 1975 by a Chinese study. In 2005, China again measured the altitude of the mountain and got a result of 8844.44 m s. no. m. Thus began a discussion between China and Nepal that lasted for five years, from 2005 to 2010. China argued that the measurement should be made up to the altitude of the rock, which is 8844 m a.s. no. m., but Nepal objected that it should be done up to snow altitude, which is 8848 m a.s.l. no. m.. In 2010, both nations agreed that the altitude of the mountain is 8848 m a.s.l. no. m., and Nepal acknowledged China's claim that the altitude to the rock of Everest is 8,844 meters (previously, in May 1999, a US team had measured a height of 8,850 meters using GPS technology).

Ascension

Mount Everest attracts many climbers, some of them highly experienced mountaineers. There are two main routes of ascent: one approaches the summit from the southeast in Nepal (known as the standard route) and the other from the north in Tibet. Although the standard route does not pose considerable technical climbing challenges, Everest presents dangers such as altitude sickness, weather and wind; as well as significant risks such as avalanches and crossing the Khumbu icefall. As of 2016, about 200 corpses remain on the mountain, some of which serve as reference points.

The first documented efforts to reach the summit of Everest were made by British mountaineers. With Nepal barring access to foreigners at the time, the British made several attempts on the North Ridge route on the Tibetan side. The First British Everest Survey Expedition in 1921 reached just 7000 m a.s.l. no. m. by the North Col. The 1922 expedition reached 8320 m s. no. m. by the North Ridge route, the first time a human climbed above 8000 m s. no. m.. While descending the North Col, tragedy struck when seven porters were killed in an avalanche. The 1924 British Expedition turned out to be Everest's biggest mystery to this day: George Mallory and Andrew Irvine made a final attack on the summit on June 8, but never returned, raising a mystery as to whether they were the first to reach the top. They were seen on top of the mountain that day, but disappeared into the clouds and were not seen again, until Mallory's body was found in 1999 at 8155 m s. no. m. on the north face. During the 1953 British Expedition, Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary achieved the first official ascent using the Southeast Ridge route. Tenzing had reached 8595 m s. no. m. a year earlier, as a member of the 1952 Swiss Expedition. The Chinese mountaineering team consisting of Wang Fuzhou, Gongbu and Qu Yinhua achieved the first documented ascent of the peak from the North Ridge on May 25, 1960.

Western Discovery

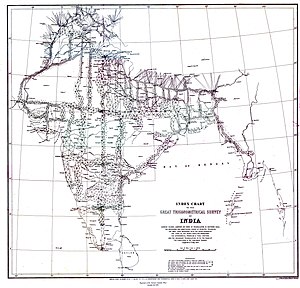

In 1802, the British government began the Great Project of Trigonometric Surveying of India to determine the location, elevation, and names of the highest mountains in the world. Beginning in southern India, reconnaissance teams advanced north using giant theodolites, each weighing 500 kg (1,100 lb) and requiring at least twelve men to move, so altitudes could be measured with the highest possible precision. They reached the foothills of the Himalayas in the 1830s, but the Nepalese government was unwilling to allow the British into the country due to suspicions of political aggression or possible annexation. Several requests by reconnaissance teams to access Nepal were denied.

The British teams were forced to continue their observations from the Terai, a region in southern Nepal that runs parallel to the Himalayas. Conditions in the Terai were difficult due to torrential rains and malaria. Three expedition officers died of malaria and two others had to retire due to failing health.

In 1847, however, the British continued the Great Surveying Project and began detailed observations of the Himalayan peaks from observing stations 150 miles (240 km) away. The weather made work difficult the last three months of the year. In November, Sir Andrew Waugh, the Surveyor General of India, made several observations from the Sawajpore Station, located in the far eastern Himalayas. Kangchenjunga was then considered the highest peak in the world, and with interest, he observed a peak behind it, about 230 km (140 miles) away. John Armstrong, one of Waugh's officers, also observed that peak from a location far to the west and named it Peak b. Waugh would later write that observations indicated that Peak b was higher than Kangchenjunga, but due to the great distance of the observations, closer observations were required to verify this. The following year, Waugh sent a scouting officer back to the Terai to take a closer look at Peak b, but cloud cover thwarted any attempt.

In 1849, Waugh sent James Nicolson to the area, who made two observations from Jirol, 120 miles (190 km) away. Nicolson then took the largest theodolite and headed east, obtaining about 30 observations from five different locations, the closest being just 174 km (108 mi) from the peak.

Nicolson went back to the city of Patna, on the Ganges, to make the necessary calculations based on his observations. Raw data from him gave a mean height of 9,200 m (30,200 ft) for peak b, but without considering light refraction, which distorts altitude measurements. However, the number clearly indicated that peak b was higher than Kangchenjunga. Nicolson then fell ill with malaria and was forced to return home without finishing his calculations. Michael Hennessy, one of Waugh's assistants, began naming peaks based on Roman numerals, with Kangchenjunga named Peak IX, while Peak b became Peak XV.

In 1852, stationed at the exploration barracks at Dehradun, Radhanath Sikdar, an Indian mathematician and explorer of Bengal, was the first to identify Everest as the world's highest peak using trigonometric calculations based on Nicolson's measurements. The official announcement that the XV peak was the highest was delayed by several years due to the calculations being repeatedly verified. Waugh began working on Nicolson's data in 1854, and together with his team they spent almost two years working on the calculations, having to deal with problems such as the refraction of light, barometric pressure, and temperature over the great distances where they were found. made the observations. Finally, in March 1856, he announced his results in a letter addressed to his representative in Calcutta. The height of Kangchenjunga was stated to be 8,582 m (28,156 ft), while Peak XV was given the elevation of 8,840 m (29,002 ft). Waugh concluded that Peak XV was "most likely the highest peak in the world." publicly stated as 29,002 feet (8,839.8 m), this to avoid the impression that an elevation as accurate as 29,000 feet (8,839.2 m) was no more than a rounded estimate. Waugh is therefore, wittily credited as "the first person to set two feet on top of Everest".

Altitude measurement

The altitude of 8848 m s. no. m. is officially recognized by Nepal and China, however, Nepal is planning a new measurement study.

In 1856, Andrew Waugh said that Mount Everest (then known as Peak XV) was 8840 m s. no. m. altitude, after several years of calculations based on observations made by the Great Trigonometric Topography Project.

The altitude of 8848 m s. no. m. It was determined in an Indian study carried out in 1955, moving closer to the mountain and also using theodolites. This altitude was ratified in 1975 by a Chinese measurement. In both cases the top of snow and not rock was measured. In May 1999, a US expedition, led by Bradford Washburn, placed a GPS on the rock at the top. The device obtained an altitude of 8850 m s. no. m. for rock and 1 m for snow and ice cover. Although Nepal has not officially recognized it, this figure is widely quoted. In any case, the geoid shape of the Earth casts doubt on the precision shown by the 1999 and 2005 measurements, and on the usefulness of determining altitude with such high precision. A detailed photogrammetric map (1:50,000 scale) of the Khumbu region, including the southern part of Mount Everest, was made by Erwin Schneider as part of the 1955 International Himalayan Expedition, which also included a unsuccessful attempt to climb Lhotse. An even more detailed topographic map of the Everest area was produced in the late 1980s, under the direction of Bradford Washburn, using aerial photographs.

On May 22, 2005, the Everest Expedition team from the People's Republic of China ascended to the top of the mountain. After several months of complex measurements and calculations, on October 9, 2005, the State Bureau of Mapping and Surveying announced that the altitude of Everest is 8844.43 ±0.21 m and stated that it is the most accurate measurement ever made. date. This new altitude is based on the highest point of the summit rock and not on the snow and ice on top of the rock. The Chinese team also measured the depth of ice and snow as 3.5 m, which is in agreement with the altitude of 8,848 m s. no. m. calculated above.

More recently, new calculations of its altitude have been made, resulting in 8848 m s. no. m. (29,029 ft), although there is some variation in measurements. After Everest, the highest mountain is K2, with 8611 m s. no. m. (28,251 feet).

Mount Everest is still rising and moving northeast, driven by plate tectonics in the South Asian area. Two sources suggest the rate of movement is 4 mm per year in elevation and 3-6 mm to the northeast. A decrease in its altitude has even been suggested.

The lowest point of the ocean is deeper than the height of Everest: the Challenger Deep, which lies in the Mariana Trench, is so deep that if you were to sit on the bottom of Everest you would be more than 2km away to reach the surface.

The Mount Everest region, and the Himalayas in general, are experiencing melting ice and snow loss possibly due to global warming.

Comparisons

The top of Everest is the point where the Earth's surface reaches the greatest distance above sea level. Several mountains are sometimes alternately claimed as the "highest mountains on Earth." Mauna Kea in Hawaii rises to more than 10,200 m when measured from its base on the mid-ocean floor, but it only reaches 4,205 m above sea level. sea level.

By the same measure from bottom to top, Denali in Alaska, formerly known as Mount McKinley, is also taller than Everest. Although its elevation above sea level is only 6,190 m, Denali lies on top of a sloping plain with elevations of 300 to 900 m, producing an altitude above base in the range of 5,300 to 5,900 m; a commonly quoted figure is 5,600 m. By comparison, elevations for Everest are from 4,200 m on the southern side to 5,200 m on the Tibetan Plateau, yielding an altitude above base in the range of 3,650 to 4,650 m.

However, if the measurement is made from the center of the Earth, Mount Everest is 6,382,605 km away and the Chimborazo volcano, located in the Republic of Ecuador, is 6,384,416 km away. So Chimborazo is 1.8 km higher than Everest. This is due to the geoid shape of the Earth.

Geology

Geologists have subdivided the rocks that comprise Mount Everest into three units called formations. Each formation is separated from another by low-angle faults called strike-off faults, along which they have been pushed over one another to the south. From the top of Mount Everest to its base, these rock units are: the Qomolangma Formation, the North Col Formation, and the Rongbuk Formation.

Formation of Qomolangma

The Qomolangma Formation, also known as the Jolmo Lungama Formation or the Everest Formation, runs from the summit to the upper reaches of the Yellow Band, about 8,600 m (28,200 ft) above sea level. It consists of parallel sheets of gray to dark gray or white, Lower Ordovician limestone interspersed with secondary beds of recrystallized dolomite with sheets of clay and siltstone. Swiss scientist Augusto Gansser documented finding microscopic fragments of crinoids in the limestone. Subsequent petrographic analysis of limestone samples collected near the summit revealed them to be composed of compressed carbonate stones and finely fragmented remains of trilobites, crinoids, and ostracods, all of them marine organisms. Other samples were so badly cut and recrystallized that their original components could not be determined. A thick whitish, eroded layer of thrombolites 60 m (200 ft) thick comprises the base of the Third Step, and the base of Everest's pyramidal summit. This layer, which emerges starting 70 m (230 ft) below the summit of Everest, is composed of sediments trapped, imprisoned, and held together by biofilms of microorganisms, especially cyanobacteria, from shallow marine waters. The formation of the Qomolangma is interrupted by several high-angle faults terminating in the low-angle normal fault, the Qomolangma Detachment Fault. This takeoff failure is separated from the underlying Yellow Band. The lowest five meters of the Qomolangma formation overlying this fault is highly deformed.

Formation of the North Col

The bulk of Mount Everest, between 7,000 and 8,600 m (23,000 and 28,200 ft), consists of the North Col formation, of which the Yellow Band forms the upper part between 8,200 and 8,600 m (26,900 at 28,200 feet). The Yellow Band is made up of interbedded layers of diopside-epidote marble from the Middle Cambrian period, which gives it a distinctive yellowish-brown color, and muscovite-biotite phyllite and schist. Petrographic analysis of marble collected at 8,300 m (27,200 ft) found it to consist of 5 percent recrystallized fragments of crinoid ossicles. The uppermost five meters of the Yellow Band that lies adjacent to the Qomolangma detachment fault is highly deformed. A fault breccia 5–40 cm (2–15.7 in) thick separates it from the overlying Qomolangma formation.

The remainder of the North Col formation, between 7,000 and 8,200 m (23,000 to 26,900 ft) Mount Everest, consists of interbedded and deformed layers of schist, phyllite, and minor marble. Between 7,600 and 8,200 m (24,900 and 26,900 ft), the North Col Formation consists primarily of quartz-biotite phyllite and chlorite-biotite phyllite interspersed with lesser amounts of biotite-serisite-quartz schist. Between 7,000 and 7,600 m (23,000 and 24,900 ft), the lower North Col consists of biotite-quartz schist interspersed with biotite-calcite-quartz schist and quartzized marble. These metamorphic rocks appear to be the result of metamorphism of deep-ocean sedimentary rocks from the Middle Cambrian to Early Cambrian period, composed of interbedded layers of shale, shale, clayey sandstone, calcareous sandstone, greywacke, and sandy limestone. The base of the North Col formation is a regional low angle normal fault called the "Lhotse takeoff fault".

Rongbuk Formation

Below 23,000 feet (7,000 m), the Rongbuk Formation lies below the North Col Formation and forms the base of Mount Everest. It is made up of grade K sillimanite-orthoclase schist and gneiss mixed with sheets and dikes of leucogranite with a thickness grade of 1 cm at 1,500 m (0.4 to 4,900 ft). These leucogranites are part of a belt of intrusive rocks of the Late Oligocene-Miocene period, known as Upper Himalayan leucogranite. They formed as a result of the partial melting of high-grade metasedimentary rocks of the upper Himalayan sequence from the Paleoproterozoic to Ordovician period, about 20 to 24 million years ago during the subduction of the Indian Plate.

Mount Everest is formed by sedimentary and metamorphic rocks that have been pushed southward over the continental crust, composed of Archeozoic granules from the Indian Plate during the Cenozoic collision of India with Asia. Current interpretations argue that the Qomolangma and North Col formations are formed by marine sediments that accumulated within the northern continental shelf, and the continental boundary of India prior to the collision with Asia. The Cenozoic collision of India with Asia subsequently deformed and transformed these strata while pushing them southward and upward. The Rongbuk Formation is formed by a sequence of high-grade metamorphic rocks and granitic rocks derived from the alteration of high grade metasedimentary rocks. During India's collision with Asia, these rocks were pushed down and north as they were overridden by other strata; heated, transformed, and partially molten at depths greater than 15 to 20 kilometers (9.3 to 12.4 mi) below sea level; and then forced up to the surface pushed south between two major detachment faults. The Himalayas rise about 5 mm per year.

Flora and fauna

Endemic flora and fauna on Everest are very rare. There is a moss that grows at 6480 m s. no. m. on Mount Everest. It may be the plant species that occurs at the highest altitude. An alpine plant called Arenaria is known to grow below 5500ms. no. m. in the region.

Euophrys omnisuperstes, a small spider in the family salticidae, has been found at elevations as high as 6700 m a.s.l. no. m., possibly becoming the non-microscopic animal that permanently inhabits the highest altitude on Earth. It hides in small crevices and can feed on frozen insects blown there by the wind. It should be noted that there is a high probability of finding microscopic life at even higher altitudes. Birds, such as the Indian goose, have been seen flying in high parts of the mountain, while others, such as choughs, have been observed as high as the South Col at 7920 m s. no. m. Greater-billed choughs have been recorded flying at an altitude of 7,900 m (26,000 ft) and the aforementioned geese migrate over the Himalayas. As early as 1953, George Lowe of the famous Tenzing expedition and Hillary had noticed these birds fly over Mount Everest.

Yaks are often used to carry equipment for climbs on Mount Everest, can carry up to 100kg, have thick fur and big lungs. Common advice for those in the Everest region is to be on rougher terrain high when yaks or other animals are around, as they can kick people off the mountain if you are standing on the edge of the road. Other animals in the region include the Himalayan tar, which is sometimes preyed on by leopards The Tibetan black bear can be found at an altitude of 4300 m a.s.l. no. m. and the red panda inhabit the same region. A scientific expedition found a surprising variety of species in the region, including rock rabbits that eat their own feces and ten new species of ants.

Atmosphere

In 2008, a new weather station was commissioned at an altitude of 8,000 m (26,246 ft). The first report from the station was air temperature −17 °C (1 °F), humidity relative 41.3%, atmospheric pressure 382.1 hPa (38.21 kPa), wind direction 262.8°, wind speed 12.8 m/s (28.6 mph, 46.1 km/h), global solar radiation 711.9 watts/m², and UV index 30.4 W/m². The project was implemented by SHARE "Stations at High Altitude for Research on the Environment" (High Altitude Stations for Environmental Research), who also set up a webcam in 2011. The weather station is located on the South Col and runs on solar energy.

One of the problems climbers face is the frequent presence of strong winds. The tip of Everest extends into the upper troposphere and cuts through the stratosphere, leaving it exposed to the fast, freezing winds of the jet streams In February 2004, a wind speed of 175 mph (280 km/h) was recorded at the summit, and 100 mph (160 km/h) winds are common. These winds can knock climbers off their feet. Climbers wait for 7-10 day windows of opportunity in the spring and fall, when the monsoon season is either beginning or ending and the winds are weakest. Air pressure at the summit is approximately one-third that of sea level, and by Bernoulli's principle, winds can further lower the pressure, causing an additional 14% reduction in oxygen in climbers. The reduction in oxygen availability comes from the reduced overall pressure, not from a reduction in the ratio of oxygen to other gases.

In the summer, the Indian monsoon brings warm, moist air from the Indian Ocean to the south side of Mount Everest. During winter the jet air flowing from the east/southeast moves south and hits the summit.

Climate

As for the weather, it can simply be said to be extreme. In January, the coldest month, the average temperature at the summit is -36 °C and can even reach -70 °C. In July, the warmest month, the average temperature at the summit is -20°C. With the wind, the thermal sensation is less than what is indicated on the thermometer.

Permissions

In 2014, 334 permits were issued to climb it, granted free of charge due to the tragedy that struck them. By 2015, 357 permits were issued to climb Everest, but the mountain was closed again by an avalanche caused by an earthquake. Nepal extended unused permits from 2014/2015 to 2019 (Nepali permits cost around 10,000 USD for foreigners). Thus, people who bought a permit in 2014 or 2015 can use it for an Everest expedition until 2019 (usually these permits are only valid for one year). This is a clear example of the hospitality that characterizes Nepalis; an extension was specially requested by commercial expedition companies (which in turn bring resources to the country through mountaineering). Nepal is essentially a 'fourth world' country, one of the poorest non-African countries and the 19th poorest country in the world. Despite this, Nepal has been very welcoming to tourists and established a significant tourism industry.

Cost of guided climbs

Climbing with a "celebrity guide", who is usually a renowned mountaineer with extensive experience and usually multiple ascents of Everest, could cost around £100,000 in 2015. On the other hand, hiring a climbing service Limited support, which includes only some food at base camp and bureaucratic expenses like permits, can cost at least $7,000.

Commercial expeditions

Climbing Mount Everest is relatively expensive for mountaineers. The equipment needed to reach the summit can cost upwards of $8,000, and most climbers require bottled oxygen to make the ascent, which adds another $3,000 or so. The permit to access the southern part of Everest via the Nepal route costs from USD 10,000 to USD 25,000 per person, depending on the size of the team. The ascent starts from either of the two base camps close to the mountain, both camps are located approximately 100 km (60 miles) from Kathmandu, and 300 km (190 miles) from Lhasa, which are the closest cities with commercial airports.. Transporting the equipment from the airport to the base camp can cost around 2000 USD.

In 2016, most guide services cost between USD 35,000 and USD 200,000. However, the services offered can vary widely depending on the negotiation that each contractor makes, and that is usual when dealing with one of the poorest and least developed countries in the world. Tourism accounts for four percent of Nepal's economy, and a porter on Everest can earn twice the national median wage in a region where other sources of income are scarce.

Costs, due to these and other factors, are highly variable. It is technically possible to reach the summit with minimal additional expenses, with "cheap" that offer logistical support for low-cost ascents, which many in the mountaineering world consider reckless and dangerous. Many climbers hire 'full-service' commercial expeditions, which provide a wide range of services, including permit acquisition, transportation to and from base camp, food, camping tents, fixed ropes, medical assistance in the mountains, an experienced mountaineering guide, and even personal porters to load backpacks and prepare food. The cost of such a guided service ranges from USD 40,000 to USD 80,000 per person. Since most equipment is carried by Sherpas, clients of full-service commercial expeditions can often carry backpacks weighing less than 10 kg (22 lbs.), or hire a Sherpa to carry your backpack as well.

According to Jon Krakauer, the era of commercialization of Everest began in 1985, when the summit was reached by an expedition led by David Breashears, which included Richard Bass, a 55-year-old businessman at just 4 years of climbing experience. At the beginning of the 1990s, there were already several companies offering guided trips to the summit. Rob Hall, one of the climbers who died in the 1996 disaster, had successfully carried 39 clients to the summit prior to the aforementioned disaster.

The degree of commercialization on Mount Everest is often criticized. Jamling Tenzig Norgay, son of the notorious Sherpa Tenzing Norgay, said during an interview in 2003 that his late father would have been surprised to discover that wealthy people were seeking of emotions and without experience in climbing routinely reached the summit. "You have to climb this mountain on your own two feet. But the spirit of adventure is gone. Has been lost. There are people who go there with no idea how to put on their crampons. They're out there escalating because they paid someone $65,000. It is very selfish. It endangers the lives of others."

Reinhold Messner expressed himself in 2004 in this sense: «You could die on each climb and that meant that you were responsible for yourself. We were real mountaineers: careful, aware and even fearful. By climbing mountains we weren't learning how big we were. We were discovering how fragile, weak and fearful we are. You can only discover this if you expose yourself to a very high danger. I have always said that a mountain without dangers is not a mountain... High altitude mountaineering has become a tourist show. Those commercial trips to Everest are still dangerous. But the guides and the explorers and organizers tell the clients: "Don't worry, everything is organized." The route is prepared by hundreds of Sherpas. There is extra oxygen at all the camps on the way to the top. There are people who will cook the food and make the beds. Customers feel safe and don't worry about risks."

However, not all opinions about it among prominent mountaineers are strictly negative. For example, Edmund Hillary, who stated that he disliked "the commercialization of mountaineering, particularly Mount Everest", stating that "paying someone $65,000 span> and being led up the mountain by a couple of experienced guides...it's not really mountaineering." However, he noted that he was pleased with the changes brought by Westerners to the Everest area. «I do not regret it, because I worked a lot to improve the conditions of the local people. When we first arrived there were no schools or medical facilities; in all these years we have built twenty-seven schools, we have two hospitals and a dozen medical clinics, and we have built bridges over wild mountain rivers and installed fresh water pipes, so in cooperation with the sherpas we have done a lot to benefit them.”

Mountaineer Richard Bass, in an interview, responded about Everest climbers and what it takes to survive there: “Climbers need to have high altitude experience before attempting really high mountains. People don't know the difference between a 20,000 foot mountain and a 29,000 foot mountain. It's not just arithmetic. The decrease in oxygen in the air is proportional to altitude, but the effects on the human body are disproportionate following an exponential curve. People who climb Denali (20,320 feet) or Aconcagua (22,384 feet) think, "Damn, I felt great up there, I'm going to try to climb Everest." But it's not like that."

Climbing routes

Mount Everest has two main routes of ascent: the southwest face route, or via the South Col, from Nepal, and the northeast route, or via the North Col, from Tibet, as well as thirteen other less frequented routes. Of the two main routes, the easiest technically and most used is the southwest. It was the route used by Hillary and Tenzing in 1953 and the first of fifteen routes described in 1996. This was, however, a choice dictated more by politics than technique, as the Chinese border was closed to foreigners. in 1949, after China invaded Tibet. Reinhold Messner (Italy) summited alone for the first time, without oxygen or any other aid, by the more difficult north-west route, traversing the North Col towards the North Ridge and the Great Corridor, on August 20, 1980. Messner reached the summit after climbing for three consecutive days, all alone, from base camp, located at an altitude of 6,500 m s. no. m.. This route is number 8 to the top.

Most of the attempts are made between April and May, before the start of summer, the monsoon season. A change in jet streams at this time of year reduces the average wind speed at higher elevations on the mountain. Although climbing attempts are made after monsoons as well, in September and October, snow deposited by the monsoon and the less stable climate makes the climb more difficult.

South Col Road

The ascent by the southwest route begins with an approach to base camp, located at an altitude of 5380 m s. no. m., in the southern area of Everest, in Nepal. The expedition usually travels to Lukla (2860 m a.s.l.) from Kathmandu and passes through Namche Bazaar. Climbers then trek to base camp, which takes six to eight days and allows them to acclimatize to the altitude and prevent mountain sickness. Equipment and provisions are moved by yaks, dzos, and porters to the base camp. base camp on the Khumbu glacier. When Hillary and Tenzing climbed Everest in 1953, they started from the Kathmandu Valley, as there were no roads to the east of the country at the time.

Climbers typically spend a couple of weeks at base camp, acclimating to the altitude. During this time, the expedition Sherpas and climbers will put ropes and ladders on the Khumbu Icefall. Cracks and unstable blocks of ice make the icefall one of the most dangerous sections on the route. Many climbers and sherpas have died on this stretch. To reduce the danger, the climb usually begins before dawn, when the low temperatures keep the ice blocks fixed. Above the glacier is Base Camp I, or Advanced Base Camp, at an altitude of 6,065 m a.s.l. no. m..

From camp I, the expedition members cross the Western Cwm (valley, in Welsh) to the wall at the base of Lhotse, where camp II is established, at 6,500 m s. no. m. altitude. The Western Cwm is a glacial valley that rises slightly, but is marked by large transverse cracks towards the middle of the valley, which prevent direct access to the upper reaches of the valley. Climbers must cross all the way to the right until they reach the base of the Nuptse and pass through a corridor known as the "Nuptse corner". The Western Cwm is also called the "valley of silence", as its closed topography reduces the wind on the route. The high altitude and a clear, windless day can make the Western Cwm unbearably hot for climbers.

From camp II, climbers ascend the north face of Lhotse over a section prepared with fixed ropes to camp III, located on a platform at 7,470 m s. no. m.. From there, it is another 500 meters to Camp IV on the South Col, at 7920 m a.s.l. no. m.. From camp III to camp IV, you have to overcome two more challenges: the Espolón de los Ginebrinos and the Yellow Band. The Genevan Spur is a black rock outcrop named after the 1952 Swiss expedition. Ropes along the course help climbers climb over the snow-covered rock. The Yellow Band is an interspersed section of marble, phyllite and schist that requires about 100 m of rope to cross.

At the South Col, the mountaineers enter the death zone. Climbers have only two or three days of resistance at this altitude to attempt assaults on the summit. Clear weather and little wind are of great importance when deciding to make an attempt to reach the summit. If the weather is not favorable these days, the climbers must descend, in many cases to the base camp.

From Camp IV, climbers should begin the ascent around midnight, hoping to reach the top in ten to twelve hours. First the Balcony is reached, at 8400 m s. no. m., a small platform on which to rest while watching the peaks to the south and east at sunrise. Continuing along the ridge, they come across some imposing rock steps that force them to enter waist-deep snow, which represents a significant risk of avalanches. At an altitude of 8750 m s. no. m., a small tabletop-sized formation of ice and snow marks the southern summit.

From the south summit, climbers continue up the southeast ridge, known as "ledge traverse," where snow covers jagged rocks. This is the section where climbers are most exposed, as one misstep spells disaster, either to the left (2,400m drop down the southwest slope) or to the right (3,050m drop down the face of the Kangshung). At the end of this traverse is the imposing 12 m high rock wall called Hillary's Step, at a height of 8760 m a.s.l. no. m..

Hillary and Tenzing were the first climbers to climb the "step," doing so with rudimentary equipment and no fixed ropes. Today this step is overcome with ropes installed by the Sherpas. Once overcome, the rest of the climb to the top is comparatively simpler and easier, with a moderate slope covered in snow, but in which the climber is very exposed, especially while traversing long sections of snow. Also after Hillary's step you must pass a rocky and shifting area with a tangle of ropes that can be problematic, especially in bad weather.

Climbers should leave the "Top of the World" in less than half an hour, as it is necessary to descend to Camp IV before nightfall, or before supplemental oxygen runs out.

North Col Road

The North Col route begins north of Everest in Tibet. The expeditions reach the Rongbuk Glacier, establishing base camp at 5,180 m a.s.l. no. m., on a gravel plain just below the glacier. To reach Camp II, climbers ascend the central moraine of the eastern part of the glacier to the base of Mount Changtse at 6,100 m a.s.l. no. m. (20,000 feet). Camp III (advanced camp) is located under the North Col, at 6,500 m a.s.l. no. m.. To reach Camp IV, of the North Col, the mountaineers ascend the glacier to the foot of the pass, where fixed ropes allow them to reach the North Col, at 7010 m s. no. m. (23,000 feet). From there, the rocky North Ridge is ascended until reaching Camp V, at 7775 m s. no. m. (25,500 feet). The route continues along the north face through a series of ravines and precipices, in terrain with rocky plates, until reaching Camp VI, at 8,230 m s. no. m..

From camp VI, the final ascent to the top is made by the Northeast ridge. Climbers must pass three bands of rock known as the First Step (8,500 to 8,534 m a.s.l.), the Second Step (8,575 to 8,625 m a.s.l.), and the Third Step (8,690 to 8,800 m a.s.l.). Once passed, there is a steep incline (50 to 60 degree incline) to the top.

West Ridge/Horbein Corridor

This edge divides the north and south faces. Starting from camp II of the southern route, take the ridge at 7,300 m. Going into the North face and going up to the top through the Horbein corridor, a route of great technical difficulty.

Southwest Face

This route begins from camp II of the southern route, you have to go up to the right of a snow spillway up to 7800 m and at this point the wall becomes more vertical, a rocky ledge of 300 m stands out, for later, you ascend through a gutter until you arrive before the top on the normal southern route.

West Ridge

You start from the base camp of the southern normal route, you continue along the ridge, facing many climbing steps. There is a detour to the north face at an altitude of 8,500 m. This to avoid climbing the well-known "Grey Step".

South Pillar

It begins in camp III of the normal south route, instead of going up to the South Col by the Lhotse wall, it follows the pillar that comes down from the top.

Japanese Runner

An extremely difficult and high-risk route. Starting at the base of the north wall, this face is scaled up the Horbein corridor.

Messner Route

This follows the normal north route, from camp II it goes into the north face until it reaches the "great corridor" or Norton Corridor. From there you go up until you reach the normal north route, almost when you reach the top. On this route, the Three Steps of the normal northern route are avoided. Reinhold Messner climbed this new route alone, without oxygen and in the monsoon season. This route has never been repeated.

American Buttress

Across the unknown east wall of Everest. It ascends by a pillar up to 8000 m and at this point it joins the normal southern route.

Top

The routes share a common point, the summit itself. The summit of Everest has been described as being "the size of a dining table". The summit is covered in snow, ice, rock, and snow cover thickness varies from about year to year. The top rock is formed by limestone from the Ordovician period and is a low-grade metamorphic rock according to Montana State University.

Below the summit is an area known as the "rainbow valley", littered with corpses still wearing their colorful winter clothes. Below 8,000 m is an area commonly called the "death zone" », due to the danger of altitude and low oxygen pressure.

Below the summit, the slopes of the mountain slope down toward its three main sides, or faces, of Mount Everest: the North face, the Southwest face, and the Kangshung face.

Ascents

Introduction

As the highest mountain in the world, Mount Everest has attracted considerable attention and climbing attempts. A set of ascent routes has been established through several decades of mountain climbing expeditions. Whether the mountain was climbed in ancient times is unknown; it may have been climbed in 1924.

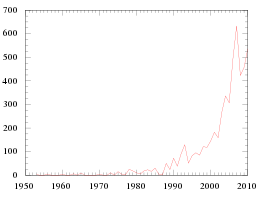

It is finally known that it was climbed in 1953, but for decades it remained a difficult peak. Despite the efforts and attention poured into expeditions, the summit was climbed by only about 200 people by 1987. Everest proved to be a difficult place for years, even for professional climbers undertaking serious attempts and large national expeditions, which were the norm until the commercial era accelerated in the 1990s.

As of March 2012, Everest was climbed 5,656 times with 223 fatalities. Although lower mountains may have longer or steeper climbs, Everest is so high that jet streams can hit it. Climbers can face winds in excess of 200 mph (320 km/h) when the weather changes. At certain times of the year the jet streams move northward, establishing periods of relative calm on the mountain. Other hazards include snow storms. and avalanches.

For 2013, the Himalayan database recorded 6,871 ascents by 4,042 different people.

First expeditions

In 1885, Clinton Thomas Dent, president of the British Alpine Club, suggested in his book Above the Snow Line that climbing Mount Everest was possible.

The northern approach to the mountain was discovered by George Mallory and Guy Bullock on the first British Everest Survey Expedition in 1921. It was an exploratory expedition not equipped for a serious attempt to climb the mountain. With Mallory leading (and thus becoming the first European to set foot on the flank of Everest) they scaled the North Col to a height of 7,005 meters (22,982 ft). From there, Mallory spotted a route to the top, but the team was unprepared for the great task of climbing any further, and they descended.

The British returned on a second expedition in 1922. George Finch ("the other George") climbed using bottled oxygen for the first time. He climbed at a remarkable speed of 290 meters (951 ft) per hour, and reached a height of 8,320 m (27,300 ft), the first time a human had managed to climb higher than 8,000 m. This feat was disregarded under the British climbing statutes—exceptions due to its 'unsportsmanlike' nature. Mallory and Colonel Felix Norton made a second unsuccessful attempt. Mallory was criticized for leading a group downhill from the North Col, which got caught in an avalanche. Mallory was swept down the slope, and seven native porters lost their lives.

The next expedition was in 1924. The first attempt by Mallory and Geoffrey Bruce was aborted because weather conditions prevented the establishment of Camp IV. The next attempt was by Norton and Somervell, who climbed without oxygen and in perfect weather, traversing the North Face into the Great Corridor. Norton managed to reach 8,550 m (28,050 ft), even though he had climbed only 30 m (98 ft) or less in the last hour. Mallory prepared the oxygen equipment for one last effort. He chose the young Andrew Irvine as his partner.

On June 8, 1924, George Mallory and Andrew Irvine, both British, made an attempt to climb to the top via the North Col, from which they never returned. In 1999, the Mallory and Irvine search expedition found Mallory's body at the expected spot near the former Chinese base camp. From that moment on, controversy arose in the world of mountaineering over whether the two mountaineers were able to reach the summit on that ascent, 29 years before Hillary and Tenzing reached it in 1953. Mallory had delivered a series of lectures in the United States the previous year, in 1923. It was then that, when asked by a New York reporter why climb Everest, (a question he had heard a thousand times) he responded exasperatedly: & #34;Because it's there.

In 1933, Lady Houston, a British millionaire former dancer, sponsored the Houston Flight of Everest of 1933, in which a formation of aircraft led by Commodore Douglas Douglas -Hamilton, 14th Duke of Hamilton and Marquess of Clydesdale, flew over the summit in an effort to display the Union Jack over the summit.

Early expeditions—such as those of General Charles Bruce in the 1920s and Hugh Ruttledge's two failed attempts in 1933 and 1936—tried to ascend the mountain from Tibet on the North Face, access denied to Western expeditions in 1950 after the People's Republic of China reasserted control over Tibetan territory. However, a small group of climbers led by Hill Tilman undertook an exploratory expedition through Nepal along what is now the usual route to Everest from the south.

The 1952 Swiss expedition to Mount Everest, led by Edouard Wyss-Dunant, was granted permission to attempt the ascent from Nepal. The expedition established a route through the Khumbu Icefall and ascended the South Col, to an elevation of 7,986 m (26,201 ft). No attempt to climb Everest had been considered in this case. Raymond Lambert and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay were able to reach a height of 8,595 m (28,199 ft) on the Southeast Ridge, setting a new altitude record on Everest. climbing. Tenzing's experience came in handy when he was recruited to take part in the 1953 British expedition.

First ascent, by Tenzing and Hillary

In 1953, a nine-member British expedition led by John Hunt, Baron of Llanfair Waterdine, returned to Nepal. Hunt selected two pairs of mountaineers for the summit assault. The first pair, Tom Bourdillon and Charles Evans reached within 100 meters of the summit on May 26 and returned to base camp. The next day the expedition made its second and last attempt with the second pair of climbers. New Zealander Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tenzing Norgay from Nepal summited at 11:30am local time on 29 May 1953 via the South Col route. At the time, both declared that it had been a team effort by the entire expedition, but years later Tenzing revealed that Hillary was the first to set foot on the summit. They stopped on the mountain to take pictures and buried some of them in the snow. sweets and a cross before descending.

News of the expedition's success quickly reached London on the morning of Queen Elizabeth II's coronation. Back in Kathmandu, Hunt and Hillary found that they had been knighted British, while Tenzing was awarded the George's Medal. Hunt eventually received a non-hereditary title in the United Kingdom, while Hillary became a founding member of the Order of New Zealand. Hillary and Tenzing are nationally recognized in Nepal, where their achievement is celebrated annually in schools and offices..

The next successful ascent was by Ernst Schmied and Juerg Marmet on May 23, 1956. They were followed by Dölf Reist and Hans-Rudolf von Gunten on May 24, 1957. Wang Fuzhou, Gonpo and Qu Yinhua of China made the first ascent of the North Col peak on May 25, 1960. Jim Whittaker, the first American to climb Everest, accompanied by Nawang Gombu reached the summit on May 1, 1963.

1970 Disaster

In 1970, Japanese mountaineers led by Saburo Matsukata carried out a major expedition whose focus was to work on finding a new ascent route on the Southwest Face, and another to attempt to ski Mount Everest. Relying on a staff of over a hundred people and a decade of planning work, the expeditions suffered eight fatalities and failed to reach the summit via their planned route. However, the Japanese expeditions enjoyed some achievements, such as that of Yuichiro Miura, who became the first man to ski down the South Col (he descended almost 4,200 vertical feet from the South Col before falling sustaining serious injuries), and an expedition that took four people to the summit for via the South Col route. Miura's exploits became the subject of a film, and he went on to become the oldest person to summit Everest in 2003 at the age of seventy, and once more in 2013 at the age of eighty.

Also, in the late 1970s, Junko Tabei of Japan became the first woman to summit Everest.

1996 disaster

During the 1996 climbing season, fifteen people died on Everest making this year one of the deadliest in Everest's history. Eight of them, belonging to three different expeditions, died on May 10 due to a storm that affected Everest. In the following month, another four people died as a result of injuries sustained that day. The disaster was well known and raised a lot of controversy about the overcrowding of Everest. Journalist Jon Krakauer, working for Outside magazine, was part of one of the affected groups and later published the book Into Thin Air (translated into Spanish under the name Altitude sickness) recounting his experience. Anatoli Bukreyev, a guide who felt singled out by Krakauer wrote a book in response called The Climb. The dispute ignited a long debate in the world of mountaineering. In May 2004, Kent Moore, M.D., and John L. Semple, Surgeon, both researchers at the University of Toronto, told New Scientist magazine that an analysis of the weather conditions that day indicated that strange weather caused the oxygen level to drop by 14%. The impact of the storm on the other side of the mountain, the North Ridge, where climbers also died, is narrated in the first person in the book The Other Side of Everest, by British director and writer Matt Dickinson.

2001 — Snowboarding down the North Face (Norton Corridor)

On May 23, 2001, French snowboarder Marco Siffredi was the first to snowboard down Mount Everest via the Norton Run, just one day after his 22nd birthday. The following year, on September 8, 2002, he disappeared without trace on his second attempt to descend Hornbein Corridor, his body was never recovered.

2003 — 50th anniversary of the first ascent

In 2003 there was a record number of expeditions to Everest, coinciding with the 50th anniversary of the first ascent.

2005 — Helicopter Landing

On May 14, 2005, French pilot Didier Delsalle landed a Eurocopter model AS 350 B3 helicopter on top of Mount Everest and remained there for two minutes. Subsequent takeoff sets the helicopter takeoff mark from the point highest, a mark that obviously can no longer be exceeded on planet Earth.

2006 — Skiing down the North Face

On May 16, 2006, adventure skier Tormod Granheim skied Norton Run, which parallels Hornbein Run. It was quite a feat.

2006 — David Sharp controversy

Mark Inglis, a double amputee after an attempt to climb, revealed in a press interview on May 23, 2006 that several groups of climbers had abandoned a struggling climber, David Sharp, on May 15, while he was staying sheltered under a rock some 450 m below the summit, without attempting to rescue him. The revelation sparked a debate about the ethics of climbing, especially as it relates to Everest. The climbers who did not render him assistance stated that rescue efforts would have been futile and would only have caused more deaths considering the number of people that would have been required to lower him. This controversy was aired by the Discovery Channel in its documentary Everest: Beyond the Boundary. A crucial decision that affected Sharp's fate is shown in the documentary. When a climber returning from the ascent finds Sharp and alerts base camp that he has found a climber with problems. It is not possible for him to identify Sharp, as he has chosen to climb solo, without support of any kind, and has not identified with any other climber. The head of the base camp assumes that Sharp is part of a group, and that they are responsible for his rescue, and orders the climber to continue on his way without knowing that Sharp has no other support, assuring from his own experience that it is impossible to rescue anyone. someone at that altitude. As Sharp's conditions deteriorate during the day, the chances of rescue are diminishing, since his legs and feet are affected by frostbite, which prevents him from walking. Other climbers on his descent are deprived of oxygen and unable to offer assistance. Finally there is no time left for some Sherpas to rescue him.

In the midst of the debate, on May 26, Australian Lincoln Hall was found alive after being presumed dead the day before. He was found by a group of four climbers, who gave up the attempt to climb him, stayed with Hall, and descended with him and a group of Sherpas sent to rescue him. Hall subsequently made a full recovery. Similar events have been documented since then, such as on May 21, 2007, when the Canadian climber Meagan McGrath successfully carried out the high-altitude rescue of the Nepalese Usha Bista. In recognition of her heroic rescue, Maj. Meagan McGrath was selected as the recipient of the Sir Edmund Hillary Foundation Canadian Humanitarian Award, which recognizes Canadians who have personally or administratively contributed significantly to some act or service in the Himalayan Region in Nepal.

Promotion statistics up to the 2010 season

By the end of the 2010 climbing season, there were a total of 5,104 ascents to the summit by at least 3,142 people, with 77% of those ascents completed since the year 2000. The summit was reached in 7 of 22 years (from 1953 to 1974), and consecutively between 1975 and 2014. In 2007, a total of 633 ascents were recorded, between 350 climbers and 253 Sherpas.

A clear example of Everest's increasing popularity is evidenced by the number of daily ascents. An analysis of the 1996 Mount Everest disaster shows that part of the tragedy was caused by the bottleneck caused by the large number of climbers (33 to 36) trying to reach the summit on the same day; this was considered too much back then. By comparison, on May 23, 2010, Everest was summited by 169 climbers, more summits in a single day than have been accumulated in the 31 years since the first successful summit from 1953 to 1983.

There have been 219 deaths on Mount Everest since the 1922 British Mount Everest Expedition, at the end of 2010, a rate of 4.3 deaths per 100 summits (this is an overall rate, and includes deaths between support climbers, those who turned back before reaching the top, those who died on the way to the top, and those who died while descending from the top). Of 219 deaths, 58 (26.5%) were climbers who reached the summit but did not complete their descents. Despite the fact that the death rate has decreased since the year 2000 (1.4 deaths per 100 summits, with a total of 3,938 summits since 2000), the significant increase in the total number of climbers still registers 54 deaths since 2000: 33 on the Northeast ridge, 17 on the Southeast ridge, 2 on the Southwest face, and 2 on the North face.

Almost all summit attempts are made using one of two main routes. The traffic seen on each route varies from year to year. Between 2005 and 2007, more than half of the climbers chose to use the more challenging northeast route. In 2008, the northeast route was closed for the entire season by the Chinese government, and the only people able to reach the summit from the north that year were the athletes responsible for carrying the Olympic torch for the 2008 Summer Olympics. it was closed to foreigners once again in 2009 in the run-up to the 50th anniversary of the Dalai Lama's exile. These closures led to a loss of interest in the northern route and, by 2010, two-thirds of climbers had reached the summit. via the southern route.

Rise Season 2012

In 2012, Montana State University conducted an expedition to Everest. The Everest Educational Expedition studied the geology of the Everest massif, which includes Everest-Nuptse-Lhotse-Khumbutse, and observed the mineralogical and they did stress studies and the dating of samples. Of interest were the fossils in the limestone that crowns Mount Everest, the nature and impact of ice in the region (such as the icefall), and the stratigraphy in general (including the limestone, metamorphic rocks, pelites and quartzites).

In 2012, the oldest woman to reach the summit to that point was 73-year-old Tamae Watanabe. She broke her previous record from 2002, when she scaled the mountain at the age of 63. The retired office worker lives in the base of Mount Fuji, and also climbed other peaks, including Denali, Eiger, and Lhotse. She also climbed with a group of four, and won a competition for 72-year-old women attempting the same record.

The death of Canadian climber Shriya Shah-Klorfine in 2012 grabbed headlines and fueled debate about whether inexperienced climbers should climb Mount Everest. Though she managed to reach the summit, she did not survive to the descent. In 1998, Francys Arsentiev died while descending despite the efforts of her husband and a team from Uzbekistan running out of bottled oxygen. In 1979, another woman named Hannelore Schmatz successfully summited, but like the two previous climbers, she became severely exhausted and ran out of oxygen despite the efforts of her climbing team to save her. Ray Genet, who was part of the same team, was also killed, but two Sherpas survived. In 1984 Yogendra Bahadur Thapa and Ang Dorje lost their lives trying to retrieve her body. Schmatz remains frozen on the mountain, her eyes wide open and her hair blowing in the wind, much to the disturbance and motional movement of later climbers in the 1980s and 1990s.

Between 1922 and 2012, at least 233 climbers were recorded to have died climbing Mount Everest. With hundreds of climbers taking the most popular route on peak days, fatalities have become almost routine, as many climbers have accepted on that some are not going to make it, and despite being left with the moral question of whether they should do more for those in trouble.

Statistics

- Until the end of 2017, 4833 people have climbed to the top in a total of 8306 ascensions, which means that 3473 ascensions have been made by people who climbed on more than one occasion, most of them sherpas. Of these, 536 were achieved by women. 288 people (171 Westerners and 115 sherpas) have died in the attempt between 1921 and 2017. The conditions of the mountain are so difficult that the vast majority of the bodies remain on the mountain. Many of them are visible from the usual climbing paths.

- The total number of attempts over the last 50 years exceeds 10,000.

- Most expeditions use oxygen masks and tanks above 8000 m. n. m. This area is called the "zone of death". Everest can be climbed without additional oxygen, a challenge achieved by 193 people before May 2016, but this increases the risk of climbing. It is difficult to think clearly without oxygen and the combination of low temperatures, difficult atmospheric conditions and hard slopes often requires quick decisions.

- Scalers are an important source of tourism revenue for Nepal. They range between experienced mountain rangers to rookies who trust the hired guides that will take them to the top. The Nepalese government obligates the payment of a climbing permit that costs $11,000 per person.

- Faster ascense along the North Collado road from field III (ABC) to the summit without additional oxygen: 16 hours and 42 minutes by Austrian Christian Stangl in 2006. Faster ascense via the South Collado without additional oxygen: 22 hours and 30 minutes by Frenchman Marc Batard in 1988. The Pemba Dorjie sherpa achieved the fastest rise with additional oxygen use via the south route with a time of 8 hours and 10 minutes in 2004.

- On 11 May 2011, Apa Sherpa, a Nepali climber, reached the summit of Mount Everest for the first time, beating its own record. The feat was matched by Phurba Tashi Sherpa and Kami Rita Sherpa.

- In 2013 Yuichiro Miura became the oldest man to reach the top of Everest with 80 years.

- Junko Tabei was the first woman to reach the top of Everest on May 16, 1975.

- Reinhold Messner achieved the first ascent to Everest alone without oxygen aid in 1980.

- On April 18, 2014, a total of 13 sherpas died and 3 more disappeared, as a huge block of ice emerged in the area known as the "Khumbu Ice Cacade", between camps I and II, on the southern side of the mountain, in Nepal.

The Death Zone

Although the conditions of any area considered a "death zone" may apply to Mount Everest (altitude greater than 8,000 m asl), the situation there is even more difficult for climbers. Temperatures can drop to very low levels, leading to freezing of any part of the body even minimally exposed to cold. With such a low temperature, the snow is completely frozen and very slippery, increasing the risk of slipping and falling. The wind speed can reach 135 km/h, also a potential danger for mountaineers.

Another threat to mountaineers is low atmospheric pressure. The atmospheric pressure at the top of Everest is about one third of the pressure at sea level, and therefore the amount of respirable oxygen is also one third of what is normal at sea level.

The wasting effects of the death zone are so strong that it takes most climbers more than twelve hours to hike a distance of 1.72 kilometers (1.07 miles) from the South Col to the summit. Even achieving this level of performance requires prolonged altitude acclimatization, taking between forty and sixty days for a standard expedition. A person accustomed to sea level exposed to atmospheric conditions above 8,500 m (27,900 ft) without acclimatizing would lose consciousness after two to three minutes.

Supplemental oxygen

Most expeditions use masks and oxygen cylinders above 8,000 m (26,000 ft). Everest can be climbed without assistance supplemental oxygen, but only by experienced mountaineers and at very high risk. Humans cannot think clearly with little oxygen, and the combination of extreme weather, low temperatures, and steep slopes often require quick and accurate decisions. While 95% of climbers who summit use bottled oxygen to get to the summit, close to 5% of climbers have summited without using supplemental oxygen. The mortality rate is doubled for those who attempt to reach the summit without the aid of bottled oxygen. Traveling above 8,000 m is a factor for cerebral hypoxia. This decrease in oxygen to the brain can cause dementia and brain damage, as well as a host of other symptoms. One study found that Mount Everest may be the hotspot higher than an acclimatized human can reach, but also found that climbers can suffer permanent neurological damage despite returning to lower altitudes.

The brain cells are extremely sensitive to the lack of oxygen. Some cells begin to die in less than 5 minutes after their oxygen source disappears. As a result, brain hypoxia can quickly cause severe brain damage or death.Healthline Website

The use of bottled oxygen to climb Mount Everest has been controversial. It was first used on the 1922 British Mount Everest Expedition by chemist George Finch and British officer Geoffrey Bruce, who climbed above 7,800 m (25,600 ft) at a spectacular speed of 1000 vertical feet per hour (pv/h). Caught in a fierce storm, they escaped death by breathing oxygen in a makeshift shelter overnight. The next day they climbed to 8,100 m (26,600 ft) at 900 pv/h, almost three times faster than a climber without supplemental oxygen. Because the use of oxygen was considered so unsportsmanlike, no one in the rest of the mountaineering world recognized this high rate of ascent.[citation needed] George Mallory himself described the unsportsmanlike use of oxygen, but later concluded that it would be impossible to summit without oxygen and consequently used it in his final attempt in 1924. When Tenzing Norgay and Hillary made their first successful summit in 1953, they both used bottled oxygen, with expedition physiologist Griffith Pugh referring to the oxygen debate as a "useless controversy" and noting that oxygen "significantly increases one's subjective appreciation of the environment, which after all is one of the main reasons for climbing". Twenty-five years ago, bottled oxygen was considered the standard at any successful summit.

Discussion about the use of oxygen

The use of oxygen cylinders for ascent has always been highly controversial. George Mallory himself described it as unsportsmanlike, but concluded that it would be impossible to reach the top without using it, and therefore used it. When Tenzing and Edmund Hillary made it to the top, they used oxygen cylinders. For the next twenty-five years oxygen utilization was considered normal for any ascent attempt. Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler were in 1978 the first climbers to break the traditional use of oxygen. Both got the first ascent to the top without using it. Messner has always denied some accusations that he used oxygen, accusations that were quelled when he ascended Everest unsupported and solo in 1980 via the more technically difficult Northwest route. In the years after Messner's ascents, the discussion about the use of oxygen continued.

The 1996 disaster intensified the debate. Jon Krakauer's book Altitude Sickness (1997) expressed his personal criticism of the use of oxygen cylinders. Krakauer wrote that the use of bottled oxygen allowed unskilled climbers to attempt the ascent, leading to difficult situations and even more deaths. The May 10, 1996 disaster was partly caused by the large number of climbers (thirty-three in one day) attempting to climb, causing traffic jams on the Hillary Step and delaying climbers, so many of them they reached the summit after two in the afternoon, the latest return time usually considered. Krakauer proposed a ban on oxygen except for emergencies, arguing, likewise, that this would prevent contamination of the mountain—large numbers of bottles accumulate on the slopes—and would prevent less-skilled mountaineers from attempting the climb.

Everest and religion

The southern part of Mount Everest is considered one of the "hidden valleys" of refuge designated by Padmasambhava, a Lotus-Born" Buddhist saint of the IX.

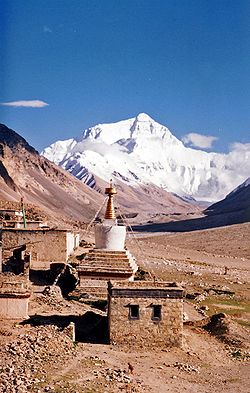

Near the base of the north side of Everest is Rongbuk Monastery, which has been called the "sacred threshold of Mount Everest, with the most breathtaking views in the world". For Sherpas living on the slopes of Mount Everest, Everest, in the Khumbu region of Nepal, Rongbuk Monastery has been a major pilgrimage site, reached within a few days' journey by crossing the Himalayas via the Nangpa La Pass.

Miyolangsangma, Tibetan Buddhist "Inexhaustible Bestower Goddess", is believed to have lived on top of Mount Everest. According to Buddhist Sherpa monks, Mount Everest is the palace and garden of Miyolongsangma, and all climbers are partly welcome guests, having come uninvited.

Sherpas also believe that Mount Everest and its flanks are blessed with spiritual energy, and reverence should be shown when passing through this sacred landscape. Here, the karmic effects of one's actions are magnified, and impure thoughts are best avoided.

Environmental problems

The opening of the Himalayas to tourism brought environmental problems due to the accumulation of waste left by the expeditions, as well as the clearing of nearby forests to obtain materials and fuel.

Waste management

Debris left behind on Everest ranges from empty oxygen bottles, tents, rope, cans or food wrappers, to human excrement and body parts.

Concerns have been expressed by both the climbing community and local authorities since the early 1980s. Since the 1990s, multiple initiatives have been proposed to control the problem, such as dedicated garbage collection expeditions, economic incentives, fines and the establishment of an NGO in charge of garbage management. These measures have made it possible to remove tons of waste and improve the conditions of the place, which came to be described as "the highest garbage dump on Earth"..

One of the last expeditions was Everest Green, a Franco-Nepalese initiative carried out in April and May 2017, which, in addition to the collection, was concerned with the final destination of the waste, incinerating the organic remains; plastics and metals were recycled in India, while batteries were recycled in France. Among his conclusions, however, he warns that conditions have worsened, which he attributes to the increase in low-cost shipments.

Human waste is one of the most dangerous wastes. They do not decompose naturally due to low temperatures and low oxygen, so they accumulate for years and, due to melting ice, contaminate the water used by villages in the lower areas. In response to this problem, the Mount Everest Biogas Project aims to create a bioreactor for the conversion of compost material, especially feces, into gas and fertilizer. The reactor was scheduled to be operational in the spring of 2019.

Filmography related to Everest

- 1975, The Man Who Skied Down Everest

- 1997 Into Thin Air: Death on Everest

- 2006, Blindsight

- 2010, The Wildest Dream: Conquest of Everest

- 2013, Beyond the Edge

- 2012, High Ground

- 2015, Everest (film)

- 2017, L'ascension

Contenido relacionado

Valderrodrigo

Amphibole

Phanerozoic eon