Moses

Moses (Hebrew, מֹשֶׁה, standard pron.: Moshe, pron. Tiberian: Mōšeh; Ancient Greek Mωϋσῆς, Mōüsēs; Latin Moyses; Arabic, موسىٰ, Mūsa), called in Jewish tradition Moshe Rabbenu (מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּנוּ, Moses our teacher), is the most important prophet for Judaism, liberating the Hebrew people from slavery in Egypt and commissioned by God to deliver the Written Law and, according to the rabbis, the Oral Law, later codified in the Mishnah.

Christianity inherited this image from Moses, whom it venerates as redeemer and legislator and, therefore, an anticipation of Christ. In both traditions, Moses is the author of the Pentateuch, in Hebrew Torah, the first five books of the Bible, which contain the Law, thus called the Law of Moses. In Islam, Moses is one of the prophets that is mentioned the most (136 times) in the Koran. In these references it is said that Moses is the messenger sent to the people of Israel and the only one to have listened directly to God, for which reason he is called kalîm Allah. The accounts of the Koran take up and sometimes rework the stories about Moses contained in the Bible and in the Haggadah, to highlight the parallelism between Moses and Muhammad, whom the former would have announced. In all Abrahamic religions, Moses is a central figure as prophet and lawgiver.

Exodus is the primary and oldest source on Moses, the sacred book recounts the life and work of the prophet, as well as his relatives and legacy. His birth occurs in Egypt, the son of Amram and Jochebed, both from the tribe of Levi. At that time, the Pharaoh (name unknown) to control the Hebrew population, issues that all male children be thrown into the Nile, the mother of Moses places him in a basket in the river from where he is picked up by Pharaoh's daughter (the midrash calls her Bithia), who raises it as her own. In his youth, he kills an Egyptian who mistreated a Hebrew and flees to the country of Midian in the desert. There he gets married and has a divine revelation on Mount Sinai.He returns to Egypt by divine order and together with his brother Aaron they demand to Pharaoh (name unknown) the freedom of the Hebrews; Faced with the sovereign's refusal, they invoke the ten biblical plagues on Egypt. Because of them, the Hebrews are released and Moses leads them to Sinai. There, he receives the Law, delivers it to the people of Israel and organizes its institutions and worship. Finally, after spending forty years in the desert, he leads the people to the Promised Land, but dies on Mount Nebo (Transjordan) before being able to enter it. The Bible does not mention where Moses was buried.

Rabbinic Judaism considers the life of Moses to extend from the year 1391 B.C. C. until 1271 a. C., while Jerome places it in 1592 a. C. and James Ussher in 1571 BC. C.

Beginning in the 17th century, the attribution of the Pentateuch to Moses was questioned, among others, by Baruch Spinoza. In the 18th century, Jean Astruc reinforced this notion with arguments of textual criticism; in both cases he did not deny the existence of Moses. From the XIX century, attempts were made to locate Moses in the New Kingdom of Egypt, relating him to figures such as Akhenaten or Ramses II.

The current consensus is that this is a legendary character, although some Moses-like tribal leader may have existed in the late Bronze Age.

Etymology

| M-S-S, Moses in hieroglyphic |

|

Moses is a name that only he bears in the entire Bible.

According to the Exodus account, his mother does not give him a name when he is born, calling him only the child. She is the daughter of Pharaoh, an Egyptian, who calls him Moses.The narrator assigns her a grammatically incorrect popular Hebrew etymology, according to which it means "saved from the waters."

Current consensus recognizes an Egyptian origin for the name. Moses is a transliteration of the Egyptian -mose, usually used as a suffix from the root m-s-s meaning "begotten of". It is common in theophoric names such as Tutmoses or Ramses.

Authors such as Naman Nadav have suggested, however, that the Hebrew root of the name cannot be left out.

Moses according to the biblical text

The story of Moses' life is narrated in the Bible, specifically in the Torah (first part of the Tanakh) and in the Pentateuch >. The biblical text narrates how Moses led the Hebrews out of Egypt and received the Ten Commandments from the hands of Yahveh on Mount Sinai. Tradition holds that Moses lived to be 120 years old.

Birth

In the Book of Exodus, the birth of Moses took place when an indeterminate Egyptian pharaoh had ordered the midwives (midwives) to kill all newborn Hebrew males, but these for fear of God they did not do as they were commanded (cf. Exodus 1:15-17). According to the aforementioned book, Moses was the son of Amram (who was a member of the tribe of Levi and descended from Jacob) and his wife, Yochebed / Jochebed (cf. Exodus 2:1; 6:20). Moses had a sister seven years older than him, Miriam, and a brother three years older than him, Aaron. According to the Book of Genesis, Amram's father, Coat, arrived in Egypt along with seventy members of the descendant group. of Jacob, so Moses was part of the second generation of Israelites born in Egypt.

Yochebed gave birth to a little one, and hid it for the first three months. When she could hide it no longer, she placed it in a basket, smeared with mud on the inside and tar on the outside to make it waterproof, and carried to the Nile. The basket with the baby was watched and closely followed by Miriam until the pharaoh's daughter reached the Nile to bathe.

A member of Pharaoh's family

The Egyptian princess (mentioned by Flavius Josephus as Termutis ) discovered the basket and Moses inside it. Miriam approached and got the princess to order a Hebrew to nurse and care for the child; the Hebrew in question was Moses' own mother.

For two years Yochebed nursed Moses and then the baby was given to the princess. Moses was raised as if he were the son of the Egyptian princess and the younger brother of the future pharaoh of Egypt.

Throughout the Mishnah, Hebrew tradition preserves an account of how Moses, even as a creature, lost much of his ability to speak due to an incident that occurred before Pharaoh in Egypt.

When Moses became an adult, he watched the work of the Hebrew slaves. One day, upon seeing the brutality with which an Egyptian foreman mistreated a Hebrew slave, Moses ended the Egyptian's life, an act that forced him to leave Egypt.

Shepherd in Midian

In the land of Midian, Moses stopped at a place with a well and there protected seven shepherdesses from a band of other malicious shepherds. The father of the shepherdesses, Jethro, was a priest of Midian. He adopted Moses as his son and allowed him to dwell in Midian; there Moisés worked as supervisor and main manager of the flocks.

In due course, Jethro also allowed Moses to marry his eldest daughter, Zipporah. Working as a shepherd, Moses lived in Midian for forty years, during which time Zipporah bore him two sons, to whom Moses called Gershom and Eliezer.

Revelation at the Burning Bush

According to the biblical narrative, on a certain occasion, Moses led his flock to Mount Horeb, and there he saw a bush that was burning without being consumed. When Moses tried to get closer to take a closer look at that wonder, God spoke to him from the bush, revealing his identity and intention to Moses:

Don't come near; remove the footwear from your feet, for the place where you are, holy land is. [...] I am the God of your father, the God of Abraham, the God of Isaac and the God of Jacob. [...] I have seen the affliction of my people who are in Egypt, and have heard their cry because of their oppressors, for I have known their troubles. Therefore I have come down to deliver them out of the hands of the Egyptians and bring them out of that land into a good and wide land, to a land that flows milk and honey [...] Come, therefore, now, and I will send thee to Pharaoh, that thou mayest bring out my people from Egypt, to the children of Israel. [...] "I am the one I am."Exodus 3:5-14.

In Exodus 3, the God of Israel reveals His nature to Moses.

Yahweh tells Moses that he is to return to Egypt and free his people from slavery. Moses expresses that he is not the candidate to carry out such a task and, furthermore, remembers that he suffers from a speech impediment. Yahweh assures him that he will provide him with all the necessary support to carry out his work.

The Ten Plagues on Egypt

Moses obeys and returns to Egypt, where he is greeted by Aaron. Both organize a meeting to inform the Israelites about what happened and, after signs, revelations and feats carried out by Moses, the Hebrews will follow him as an envoy who brings the word of Yahweh.

The most difficult thing was persuading Pharaoh to let the Hebrews go, who did not get his permission until Yahweh sent ten plagues on the Egyptians. This series of events began with the water turning to blood and culminated in the death of all the firstborn Egyptians, which caused such terror among the Egyptians that Pharaoh ended up allowing the enslaved Hebrew people to finally leave Egypt.

The Hebrew Exodus

Moses led the Israelite people eastward, thus beginning the long journey to the promised land. Some 600,000 men, not counting the children, set out from Rameses for Succoth, carrying the remains of Joseph with them, doing the will of his predecessor.

The great caravan of the Hebrews moved slowly and had to make camp three times before leaving behind the Egyptian border, then established at the Great Bitter Lake or at the northernmost point of the Red Sea.

Meanwhile, Pharaoh changed his mind and, with a large army, set out to retrieve his slaves. Caught between the Egyptian army and the sea, the Hebrews despaired, but Yahweh parted the Red Sea through the Moses, allowing the Israelites to cross it safely. When the Egyptians tried to follow them, the waters returned to their course, drowning the entire Egyptian army.

Date of Exodus. Although the Bible does not mention the pharaoh of the Exodus by name, it does give the exact date of the Exodus. In 1 Kings 6, 1 we read that Solomon began to build the Temple in the fourth year of his reign, 480 years after the children of Israel left Egypt. It is estimated that the fourth year of Solomon's reign was around the year 966 B.C. C. From this the date of Exodus could have been 1446 a. C., when Tutmosis III ruled. However, since the biblical text specifically indicates that the Hebrews left the city called "Rameses" towards Sukkot, cities that did not exist at the time of Thutmosis III and that date from the 13th century BCE. C., when Ramses II ruled Egypt, in the field of research it is considered the year 1250 a. C.H.W.F. Saggs, a professor of ancient languages, notes in his scholarly writings that:

The mention of the city of Ramess in Exodus 1:11 as a place of storage, built in part by the Israeli slaves, actually offers a chronological indication, since [today] it is known that Ramses II built a city, Per-Ramsés [i.e., Pi-Ramsés], which corresponds to the name provided by the Bible. This tends to place slavery [of the Hebrews] in Egypt and its departure from that country in the 13th century BC. It is in that same century that the first extra-biblical mention of Israel occurs. This is an inscription of the successor of Ramses [II], Merenptah.

Granting of Law

After three months (Exodus 19) had elapsed since the Hebrews had left Egypt and during the journey through the desert, God conferred the Ten Commandments directly on Moses and did so on Mount Sinai.

The Tables in question included the Ten Commandments, basic laws of obligatory compliance for the Hebrew people. Since the different Hebrew tribes:

Until then they kept faith in a unique God and some customs that had inherited from their ancestors. But they did not have a clear concept about God [...], neither did they possess fixed laws on social and moral life. Having resided in Egypt some of them copied there certain pagan customs. It was therefore necessary to teach the Israelites what their true faith consisted of and what laws should be followed.

When Moses went down to notify his people, he discovered that in his absence the Israelites had melted down precious metals and built a golden calf, in the likeness of an Egyptian four-legged idol, Apis, and he realized that they worshiped it. Eventual idolatry committed by the people provoked the wrath of God and, indignant, Moses was enraged and threw the Tablets of the Law, also destroying the golden idol. The divine prescriptions however would be rewritten and restored by Moses, being subsequently adopted by the people.

As Moses approached the camp, he saw the calf and the dances. He was filled with anger and threw the boards, which were torn to pieces at the foot of the mountainExodus 32:19

Iconographically, Moses is represented as a legislator of the Hebrew people and carrying the Tables of the Law with the Ten Commandments, these Tables being his main attribute in collective belief and visual imagery, both Jewish and Christian.

Exodus

Journey through the Sinai Peninsula

The journey through a series of inhospitable places for the great mass of people was hard and many began to spread rumors and murmur against their leaders (Moses and Aaron), arguing that it was better to be under the Egyptian yoke than to suffer the hardships of the crossing. Moses performed innumerable miracles to appease the harshness of the journey and show the people of Israel that Yahveh guided them. The divine manifestations were lavish.

To feed them, Yahveh rained down manna from heaven. To drink, he gave them multiple sources of water, such as the source of bitter water turned into sweet water. Meanwhile, Yahveh ordered Moses to speak to the rock where a great amount of water would come out, but Moses hit the rock twice with his staff, but he was enraged for hitting the rock, assuring that Moses would not enter the promised land, for this reason they called that place Meriba, that is, discussion.

In their journey through the deserts, Israel fights for the first time against the Amalekites, who were a main people and won only because of the strength of Moses. (Exodus 17:8). Israel also defeats Arad, the Amorites led by Sihon (Numbers, 21) and they surround lands where they are not allowed to fight nor are they allowed to pass through, as is the case of the lands of Edom.

On Mount Sinai, the Jewish people were doctrinally organized by the lesser priesthood of Aaron. They are instilled with statutes, commandments and, above all, developing fidelity to the agreements with Yahveh. This story is told in Leviticus.

On the same mountain, Yahveh delivers the Decalogue of the Ten Commandments, but when Moses descends with Joshua, he finds his people worshiping a golden calf. This perversion in the eyes of Yahveh was punished with death, thus in Exodus it is recounted: «And he said to them: Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel: Put each one his sword on his thigh: pass and return from door to door in the field, and kill each one his brother, and his friend, and his relative. And the sons of Levi did it according to the saying of Moses: and about three thousand men fell from the people on that day." Situations like this would happen several times on the way to the promised land.

Yahveh once again dictated his ten commandments and to transport the sacred scriptures, the ark of the alliance was built. To carry said ark, the Tabernacle was built, which would be the transport of the ark until it reached the promised land, where a temple would be built to house it.

Census of Moses

In Numbers 1, God orders Moses to take a census of all the Israelites to better organize them, this census only counted men over 20 years of age and was carried out with the collaboration of a patriarchal chief of each tribe. The tribe of Levi was counted separately as Numbers 3, all those males one month of age and older. These censuses are the reason why this Biblical book is called "Numbers" and the total counted is similar to the other census within the book of Exodus.

| Census of Moses

Only men count | |

|---|---|

| Tribu | Amount |

| Ruben | 46,000 |

| Simeon | 59,000 |

| Gad | 45,600 |

| Juda | 74,600 |

| Isacar | 54,000 |

| Zebulun | 57,000 |

| Efraín | 40,500 |

| Manasseh | 32,200 |

| Benjamin | 35,400 |

| Dan | 62,000 |

| Aser | 41,000 |

| Neftalí | 53,000 |

| Levi | 22,273 |

| TOTAL | 622,573 |

Moses sends out twelve spies

Already close to the promised land, Moses entrusts twelve spies to investigate and give a report on the benefits of the promised land. After forty days of investigation, ten of the twelve spies give an extremely discouraging report about the people who lived on these lands, instilling fear in the armed hosts and, above all, distrust of Yahveh's promises. Only Joshua (from the tribe of Ephraim) and Caleb (representative of Judah) returned and stated that God would help them to settle the Hebrew nation in Canaan.

Because of this, this is where God punished Israel by speaking to Moses and saying these words:

"You will not enter the earth to the truth, by which I lifted up my handand I swore that I would make you dwell in it, except for Caleb the son of Jephunneh and Joshua the son of Nun... According to the number of days, of the forty days in which you recognized the earth, you shall bear your iniquities forty years, one year for each

and ye shall know my punishment.

So the Israelites were forced to remain in the desert for forty more years. Finally, after forty years of wandering in the desert, the Hebrews of that generation died in the desert and the authority of Moses as leader of the people passed to Joshua.

According to these texts, Yahveh ―seeing the fear of his chosen people― prohibited the entry of all men of war (over 20 years of age) to the promised land, including Moses himself who was only allowed to see it from the top of a mountain (Nebo). It is necessary to clarify,[Why?] however, that the prohibition did not include the Levites (tribe to which Moses belonged), who were not registered for the war, nor Joshua and Caleb, who did show faith in divine promises. Moses was not allowed due to the event at Meribah.

Already being close to Moab, Balak, king of the Moabites, sees Israel coming from the eastern margin and fears the people of Israel, he sends for Balaam, a soothsayer from Mesopotamia, to curse the people of Israel; but Yahveh sends an angel to stand in the way of Balaam towards the mount of Bamot-Baal and he is persuaded to bless the Israelite people and he does so three times despite Balac's wishes.

Death of Moses

According to the Book of Numbers (20:7-13) Moses had struck a rock twice in Meribah, so that a spring of water would flow from it; this fact was seen as a sign of doubt, for which God prohibited him from entering the Promised Land, he was authorized, however, to contemplate it from the top of Mount Nebo, in Moab; there he died, in full force at one hundred and twenty years of age according to the Biblical book of Deuteronomy (34:1-9). The Talmudic tradition, from the first lines of the Book of Joshua, set the date at Adar 7. According to the Seder Olam Rabba, the year corresponds to 2488 of Creation, which is equivalent to February 12, 1272 before the Christian Era. As for the burial place, the cited text considers it unknown but later legends, collected in the New Testament by the Epistle of Judas (1:9) mention a dispute between the archangel Michael and Satan, in relation to the body of Moses.

Moses in Judaism

The main source regarding Moses is the Torah, copies of which are preserved in all synagogues and Israelite institutions. Within the sacred texts of Judaism, particularly important are the books of the Pentateuch, the final drafting of which took place in the time of the monarch Josiah, who ruled the Kingdom of Judah in the VII a. C. There is also a multitude of other documents, literature, stories and additional information about Moses in the rabbinical exegesis known as the Midrash, as well as in the compilations of the most important texts of the Jewish oral law, which are known as the Mishnah and the Talmud.

Traditionally during Pesach (Jewish Passover), and since at least the Middle Ages, observant Jews read the text of the Haggadah, which narrates the process of liberation of the Hebrews from their slavery in Egypt and the intervention of Moses in it.

Moses in Christianity

Moses is a forerunner of Jesus, often compared to them and indicates that Moses is considered a prophet and therefore bearer of the word of God. In the Gospel, the teachings and events of Jesus' life are compared to those of Moses to explain the mission of Jesus.

Moses figures in several of Jesus' messages. When he meets the Pharisee Nicodemus at night, in the third chapter of the Gospel of John, he compares the raising of the bronze serpent in the desert, which any Hebrew could look at to be healed, with his own ascension into heaven (after his death). and resurrection) so that people will see it and be healed. In the sixth chapter, Jesus responds to his followers that Moses caused manna to fall in the desert, saying that it was not he, but Yahveh, who had performed the miracle. Calling it the "bread of life", Jesus affirms that now it is he who feeds the people of Yahveh. The letter of Judas contains a brief mention of a dispute between the Archangel Michael and the devil over the body of Moses.

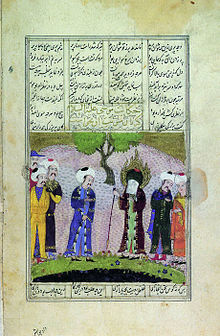

Iconographically, Moses appears in reliefs, mosaics, illuminated manuscripts, icons, stained glass windows, paintings and sculptures that respond to the different expressions of the Christian faith. Moses is also the patron saint of churches on Mount Nebo, Venice and Amsterdam.

Moses in Islam

In the Qur'an, Islam's holy book, the life of the prophet Moses (Mûsâ ibn 'Imran, Arabic: ٰمُوسَى) is quoted more than that of any other prophet (nabi) recognized by Muslims as, along with Abraham, he is considered one of the most important prophets of monotheism prior to Muhammad. The book stresses that Moses is a primarily monotheistic figure and makes few differences regarding the belief of both Hebrews as of Christians; claims that God (in Arabic Allah) revealed to him the holy book (the Tawrat, in Arabic: توراة, form of Hebrew Torah) and numerous Bible stories related to Moses they are incorporated into the Qur'anic text.

Muslims venerate the tomb of Moses, which they call "Maqam El-Nabi Musa", which is located in the territory of Palestine, about eight kilometers south of Jericho, on the road to Jerusalem.

Iconography

In the History of Art, the figure of Moses is frequent in both Jewish and Christian art; he is generally represented as a prophet with the Tables of the Law as his main attribute. He usually appears as a mature man, bearded, wearing a Hebrew tunic and a rod or staff in his hand. In images that concern the youth of Moses, he is represented with the attributes of an Egyptian prince.

Another unique attribute of Moses is the luminosity that emerges from the skin of his face and that has its ultimate referent in the biblical text, where this concept finds expression through the beam of light that made Moses' face shine after to have been in the presence of the Creator. In visual terms this is often expressed by two beams of light coming from the forehead of the man who has become a prophet.

The presence of horns (instead of the use of a beam of light) in the case of the images involving Moses is due to a misinterpretation when the Bible was translated from Hebrew into Latin: the ancient Hebrew expression keren or (קָרַ֛ן עֹ֥ור), which refers to the glowing state of Moses' face, was mistakenly interpreted by Jerome of Estridon as "horns" and included as such in the Vulgate; This led to a horned Moses in several church images of the late Gothic period, between the 14th to xvi. However, this was noticed at the time by the Church and the horns in question were thereafter replaced by shapes visually comparable to rays of light that in unequivocal terms express the radiance of the face of Moses.

In the famous case of Michelangelo's Moses, the Florentine artist resorted to a pair of horns not out of ignorance or lack of information, but because he wanted to express the notion that Moses, after his encounter with the Creator, he had been transformed and was no longer merely a man, but a practically supernatural being due to the extraordinary role he had to play before God.

In Christian imagery, both Catholic and Orthodox, when the notion of holiness is expressed, Moses can sometimes present a halo in those iconic representations that are his own.

Historicity

Historical evidence

Scholar consensus is that Moses and the Exodus as described in the Bible are mythical, although a simple majority of scholars accept the existence of a historical core to the narrative. Along these lines, various scholars have proposed a relatively small group of people of Egyptian origin who would have joined the ancient Israelites, making the historical memory of their "exodus" extended to all of Israel as a whole, and whom William G. Dever cautiously identifies with the House of Joseph, while Richard E. Friedman identifies them with the Tribe of Levi.

Extra-biblical references to Moses date back many centuries after the time in which he supposedly lived. It is unknown if they are based solely on Jewish tradition or if they have also taken aspects from other sources. Some Jewish authors such as Flavio Josefo and Philo of Alexandria or Greeks such as Diodoro Sículo point out that he is named by authors such as Hecateo de Abdera, Alejandro Polyhistor, Manetón, Apion and Queremón de Alejandría; however, the works of these writers have been lost, surviving only in citations. Of these, the most notable is Manetho, a Hellenized Egyptian priest and chronicler of the 3rd century BCE. C., who names Moses in his work on the history of Egypt ( Aigyptiaca ), which is only preserved in citations from Jewish and Christian authors. Manetho says, according to the quotes, that Moses was not a Jew, but an Egyptian priest named Osarsef. This priest was a rebel who led an army of lepers against Pharaoh Amenhotep (which one is not stated) in collusion with the Hyksos. Victorious at first, they were defeated by Amenhotep, who drove them out of Egypt; after that Osarsef changed his name to Moses and the lepers founded the city of Jerusalem. Manetho's account was partially accepted in the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century by some authors such as Schuré or Freud, who saw in it a distorted memory of the historical character. It is currently accepted that it is partly an anti-Jewish libel and partly a popular tale about the time of the Hyksos and the Amarna period.

In the light of what has been discovered about Egyptian history and culture, many researchers of the XX century, such as Kitchen, Noth and Albright, among others, have suggested an authentic background to the character. The main argument is that Moses, contrary to what the Bible says, is a name of Egyptian origin meaning "son" (it appears as mosis, moses or més in transcriptions; for example Thutmosis, son of Thoth, or Ramesses, son of Ra). In addition, some ritual laws and customs contained in the work attributed to Moses, such as the Ark of the Covenant, could be traced back to Egyptian myths and rites. On the other hand, other elements, especially the story of its abandonment in a basket placed in the river, were linked to the Mesopotamian legend of Sargon of Acad, which would be its source, and were compared with similar stories in other myths about the river. origin of the hero, especially that of Oedipus.

This interpretation, current in the middle of the XX century, was replaced by another that, in light of advances in archaeology, biblical criticism and history, called into question the very existence of Moses or reduced him to a name from Israel's past, about which little could be said. Today, those who maintain the existence of a historical core in the narrative appeal as supporting evidence the documented movements of small groups of ancient Semitics to and from Egypt during the 18th and 19th Dynasties, some elements of Egyptian folklore and culture in the Exodus narrative, and the names of Moses, Aaron, Phineas, and others, which appear to have an Egyptian origin.

On the other hand, the current of biblical minimalism, especially the works of Philip R. Davies, Niels Peter Lemche and the archaeologist Israel Finkelstein, considers that all the books of the Bible, especially the story of the Exodus, the Conquest and the reigns of Saul, David and Solomon, were composed in a late period (between the Assyrian conquest and Persian rule) on the basis of old legends altered to legitimize the religious reforms of the time.

Although certain documentaries, such as Exodus Decoded, by Simcha Jacobovici and James Cameron, insist on giving literal credibility to the Exodus story, and even claim to discover that Amosis I corresponds to the pharaoh alluded to in the Bible, such claims are considered entirely unfounded and built on the basis of fallacies by the scientific community.

Time issues

Regarding the time of Moses, the problem is linked to that of Exodus, for whose dating there are different hypotheses, but no historical evidence to confirm it:

- In the century xvi a. C., towards the end the era of the hicsos, hypothesis that relates to the account of Manetón.

- Around 1420 B.C., with the first incursions of the Habiru into Canaan. Richard Darlow identifies him with Prince Ramose, who is mentioned in Egyptian documents around the time of Hatshepsut.

- During the century xiiia. C., for the Pharaoh for most of that time was Ramses II, which is usually considered to be the Pharaoh with whom Moses had to face—known as "the pharaoh of the Exodus" or "the oppressive pharaoh"—of whom it is said to have forced the Hebrews to build the cities of Pithom and Ramesses. These cities are known to have been built under Seti I and Ramses II, making his successor Merenptah the possible "Poland of Exodus". However, in the wake of Merenptah of the fifth year of the aforementioned Pharaoh (1208 B.C.), it is told that “Israel is finished, there is neither seed left”.

- A very widespread hypothesis in the centuryXX. (now discredited by scientific research) claimed that Moses was a nobleman of the court of Pharaoh Akenaten. This idea was defended by Sigmund Freud and, with variants, by Joseph Campbell, who suggested that Moses could have left Egypt after the death of Akenaten (1358 BC), when the monotheistic reforms of the Pharaoh were violently rejected. In connection with this ideal, the contemporary Letters from Amarnawritten by the nobles for Akenaten, they describe assailant habirus bands attacking Egyptian territories.

Moses in film and television

Cinema

- 1923 - The Ten Commandments / The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

- 1956 - The Ten Commandments / The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

- 1975 - Moses und Aron / Moses and Aaron (Germany, Austria, France, Italy)

- 1998 - The Prince of Egypt / The Prince of Egypt (United States of America)

- 2007 - The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

- 2014 - Exodus: Gods and Kings / Exodus: Gods and Kings / Exodus: Gods and Kings (United States, United Kingdom, Spain)

- 2016 - Os Dez Commandments: O Filme / Moses and the Ten Commandments: The Film (Brazil)

Television

TV movies

- 1959 - The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

- 1995 - Moses / Moses (United States, United Kingdom, France, Italy, Spain, Germany, Czech Republic)

- 1997 - The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

TV series

- 1974-1975 - Moses the Lawgiver / Moses (United Kingdom, Italy)

- 1978 - Great Heroes of the Bible: The Story of Moses

- 1985 - The greatest of adventures: Bible passages, episode Moses.

- 1997 - Sixho Monogatari, In the Beginning: Bible Storiesepisodes of Moses and the Exodus.

- 2006 - The Ten Commandments / The Ten Commandments (United States of America)

- 2015-2016 - Os Dez Commandments / Moses and the Ten Commandments (Brazil) (telenovela)

Contenido relacionado

Saint Kitts and Nevis

Politics and government of Saint Lucia

Franc (currency)